Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

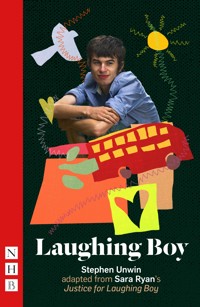

'So much magic. So much love. So much laughter. So much work. So much rage. And so many tears.' Connor is, well, Connor. He loves buses, Eddie Stobart and Lego. He also has learning disabilities. When he dies an entirely preventable death in NHS care, his mum, Sara, can't get a straight answer as to how it happened. But Sara and her family won't stop asking questions and soon an extraordinary campaign emerges. Demanding the truth, it uncovers a scandal of neglect and indifference that goes beyond Connor's death to thousands of others. Sara Ryan's impassioned, frank and surprisingly funny memoir Justice for Laughing Boy is adapted for the stage by Stephen Unwin. It was first performed at Jermyn Street Theatre, London, in 2024, in a co-production with Theatre Royal Bath.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 94

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Stephen Unwin

LAUGHING BOY

Adapted from Sara Ryan’sJustice for Laughing Boy

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Original Production Details

A Beautiful Boy, a Book and an Ink PadSara Ryan

Precious Cargo: Adapting Justice for Laughing Boy for the StageStephen Unwin

Characters

Notes

Laughing Boy

About the Authors

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

To All the Young Dudes

Laughing Boy was first performed at Jermyn Street Theatre, London, from 25 April 2024. The cast was as follows:

SARA RYAN

Janie Dee

OWEN

Lee Braithwaite

CONNOR

Alfie Friedman

WILL

Charlie Ives

RICH

Forbes Masson

ROSIE

Molly Osborne

TOM

Daniel Rainford

Writer and Director

Stephen Unwin

Author

Sara Ryan

Designer

Simon Higlett

Lighting Designer

Ben Ormerod

Sound Designer

Holly Khan

Video Designer

Matt Powell

Casting Director

Ginny Schiller CDG

Associate Director

Ashen Gupta

Assistant Director

Sam Chown-Ahern

Associate Sound Designer

Anna Wood

Assistant Video Designer

Douglas Baker

Fight Director

Enric Ortuño

Production Manager

Lucy Mewis-McKerrow

Stage Manager

Daisy Francis-Bryden

Technical Assistant Stage Manager

Grace Hancock

Costume Supervisor

Rachael Griffin

Production Carpenter

Basement 94

Production Technician

Ted Walliker

Executive Producer

David Doyle

Producers

Gabriele Uboldi Kate Johnson

A Beautiful Boy, a Book and an Ink PadSara Ryan

Connor died. He should be alive.

The Book

The book I wrote about what happened – Justice for Laughing Boy – was launched at Doughty Street Chambers six years ago with a wonderful panel of Helena Kennedy, Caoilfhionn Gallagher KC and Deb Coles, Director of the charity INQUEST. I wore a red scarfy-thing knitted by the mum of one of Connor’s teaching assistants. Members from the Oxfordshire-based self-advocacy group My Life My Choice including their President, Michael Edwards, sat in the front row and cheerfully chipped in.

Writing the book was an exercise in love and witnessing. I’d written a blog for years. Writing joy, laughter, critique and commentary. The book was a way of capturing Connor as a person and trying to make sense of the responses to his death. Following the blog, it went from hilarity and joy to utter devasation, documenting the brutality of the investigatory processes and bullshit (or worse) families face when someone dies in state ‘care’. It was written before some of these processes ended (they never end).

An Ink Pad

I was uncomfortable at the thought of being asked to sign copies of the book (what do you write?) and made a stamp with a tiny bus image to avoid this. The ink pad still works. I didn’t stamp or sign many copies in the end. Rich, Rosie, Will, Owen, Tom and George Julian had complimentary copies. I sent a copy to Michael’s sister down Dorset way. He persuaded the publisher to produce a audiobook version at the launch.

The Play

Steve Unwin began to talk about a play before lockdown. He loved the book and started work to bring it to the stage. We met in Oxford. There was further discussion, draft scripts, potential news, updates and undates. I approached this in the same way I dealt with the book. As a kind of interested bystander with a stamp and an ink pad. Vaguely surprised when the play was mentioned, passing on updates to family and friends with caveats; this may not happen.

A few months ago Steve shared the most recent version of the script (a corker) and news the play, Laughing Boy, would be on at Jermyn Street Theatre followed by a week at Bath. Wow. A meeting was held with Stella Powell-Jones and David Doyle (Artistic Director and Executive Producer) in a London pub to talk about the important stuff.

How to get this right. That was the discussion. With Thai curry.

The announcement was made on a Thursday lunchtime. The Lonely Londoners in Feb/March followed by Laughing Boy in April/May. I was at a writing retreat at Gladstone’s Library distracted by the beauty of the mushrooms as details bounced around social media.

So many messages and posts. A buzz of action, excitement and anticipation despite everything else going on. ‘Would it go up North?’ ‘Highlight of next year!’ ‘My Life My Choice are bussing to Bath.’ ‘Brilliant,’ said Norman Lamb. My mate Becca got her clipboard back out to organise the life-raft trip to London. Booked. Booked. Booked.

Someone prosaically tweeted, ‘Lots of time to do something remarkable.’

It’s already remarkable. A beautiful boy dismissed in life matters. His quirkiness, love of life and buses, humour, irreverence and courage to stick two fingers up at adversity count.

I’m setting aside my stamp and ink pad. There will be tears. So many tears, alongside laughter, bafflement and kick-ass brilliance.

Thank you, Steve Unwin.

Precious Cargo:Adapting Justice for Laughing Boy for the StageStephen Unwin

I can’t remember when I first heard about Connor Sparrowhawk and his dreadful death. I remember meeting his mother, Sara Ryan, at a disability event sometime in 2015 and watching the #JusticeforLB campaign develop on social media and in the press and did the little I could to support it. But, to my shame, it wasn’t until I read her brilliant book Justice for Laughing Boy in 2018 that I really started to understand what had happened and why it mattered so much.

In some ways the story felt personal. My second son Joey is just a year younger than Connor, and, like Connor, has learning disabilities and epilepsy. Like Connor he needs help with certain things. And like Connor he generates enormous joy in his family and friends, and laughter and love surround him wherever he goes.

But there the similarities end. Because what happened to the eighteen-year-old Connor is that he was taken from his family home and plunged into a hell that is almost impossible to comprehend.

Slade House in Oxford (now thankfully closed) was what is known as an Assessment and Treatment Unit, one of the deeply dysfunctional NHS institutions set up to help (mostly) autistic people whose care has broken down and who could benefit from a short and focused intervention.

The awful fact is, however, that these places are not fit for purpose, and people are often locked away in them for months, years even, largely forgotten about, except by their desperate families who do whatever they can to get them out.

Connor spent one hundred and seven miserable and lonely days in Slade House: no proper assessment was made, no treatment was offered, his freedoms were restricted, visits were controlled and finally, despite repeated warnings, he was left unattended in a bath where he drowned while having an epileptic seizure.

This was ten years ago: 4 July 2013.

In the face of the family’s unimaginable grief, a growing campaign for justice was created, not just to establish Southern Health’s (frequently denied) responsibility for this entirely avoidable death of a healthy young man, but to expose the many cases of neglect, cruelty and abuse which is still so often the experience of people in a wide range of medical, educational and residential institutions.

This homegrown campaign was a model of its kind, drawing together people of good will from many different backgrounds and skills, who found themselves confronted by an appalling culture of corporate buck-passing, dead-eyed denial and the vilest kind of victim blaming.

But eventually, the world took notice.

And so, a few years ago, I set out to dramatise the story for the stage: not just to tell audiences about what happened to Connor and his family, but to help them understand the challenges faced by so many people with learning disabilities and their families today.

It was a strange feeling trying to give dramatic shape to a group of people who are – with one tragic exception – very much still with us. I was determined to respect their experiences and allow audiences to feel something of their grief, their rage, and their determination to create a better world. But, of course, I knew it also had to be a vivid drama. Striking the right balance was hard.

Fortunately I had two things on my side.

The first was Sara Ryan’s book which tells us so much about the everyday life of Connor and his family. She lets us in in a way which is honest, revealing and, as with all the best writing, rich with contradiction. She offers an overwhelmingly powerful and detailed account of what led up to her son’s death and even intersperses the book with brief imaginary dialogues with Connor which I have been able to transfer almost verbatim. She also explains (and celebrates) how the #JusticeforLB campaign emerged and achieved so much in the face of bureaucratic obfuscation and the massed ranks of well-paid chief executives and their expensive lawyers.

I was also grateful to have Sara’s unwavering support for the project and have been constantly touched by her willingness to check my factual errors, correct my misunderstandings, and prompt me to be better, bolder, and braver. I would readily understand if she felt she couldn’t face revisiting the pain, but I think she knows that one of the best ways of working for the rights and dignities of people with learning disabilities today is to show just how badly things can go wrong.

Inevitably I feel a real responsibility to honour Connor’s memory in the best way I can: his family, his friends and everyone who was involved in the campaign deserve no less.

Justice for Laughing Boy is no dusty memoir: it is a living, breathing campaign which has achieved so much. But there is still so much to do if people like my Joey are to be granted the fundamental human rights and dignities that Connor was so brutally denied.

For the dreadful fact is that the approximately one and a half million people across the country who have some level of learning disability are still forgotten, neglected and mistreated. The culture of appalling negligence and evasion described in Justice for Laughing Boy is everywhere to be seen, and Connor Sparrowhawk wasn’t the first young person to die in an institution supposedly set up to help, and tragically won’t be the last.

In 2017 I wrote a play called All Our Children about the Nazi persecution of disabled children which was also staged at Jermyn Street. Laughing Boy is its dreadful but logical sequel.

A change has to come. Maybe this play can, in some small way, help to bring that about.

Characters

SARA

CONNOR

RICH

ROSIE

TOM

WILL

OWEN

And so many others

Notes

Lots of doubling except for Sara and Connor. Connor must be played by an autistic and/or learning-disabled actor.

The stage as a stage. Clean floor and simple chairs.

The cast on stage throughout. No costume changes or props. Lots of projections and film. Music and sound throughout. Movement.