Leakey's Luck E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Major General Rea Leakey was one of the Royal Tank Regiment's greatest heroes of the Second World War. As a young tank commander, he fought Rommel's Afrika Korps in the Western Desert of Egypt, before becoming trapped for six months in the siege of Tobruk and temporarily joining the Australian infantry as an honorary Lance Corporal. He later returned to the European theatre in 1944 and served as a Churchill tank commander in Normandy, the Rhine and Germany. Despite it being strictly forbidden, Leakey kept a diary throughout his soldiering career. Based on this valuable account, Leakey's Luck documents Leakey's wartime service in its entirety, and offers a view of the war through the eyes of a man who was there at the 'sharp end'. Many of his exploits were hair-raising, some even too fantastic to believe. Incredibly, Leakey's luck held out throughout the war, and he remained in the British Army until retirement in 1968.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

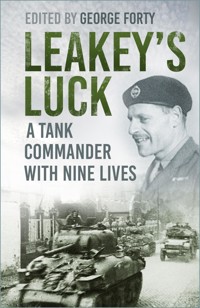

Front cover, images top to bottom: Major General Rea Leakey after receiving the Czech Military Cross (A.R. Leakey); 44 RTR passing through a French village (Tank Museum)

Back cover image: 1 RTC on manoeuvres in Egypt, 24 January 1939 (Editor’s collection)

First published 1999

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© The Estates of Rea Leakey and George Forty, 1999, 2002, 2022

The right of Rea Leakey and George Forty to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 133 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

1 Born in Kenya

2 The Western Desert

3 War

4 Operation Compass

5 ‘Fox Killed in the Open’

6 Enter Rommel

7 Locked up in Tobruk

8 A Break from the Desert

9 Backs to the Wall

10 Persia and Iraq

11 Finale in the Desert

12 On to Normandy

13 Dunkirk: September–December 1944

14 Holland and Germany

Postwar

Chronology

Bibliography

Foreword

‘Fear Naught’ is the motto of the Royal Tank Regiment of which General Leakey is such a distinguished member. Nobody could have lived up to it more fully than he, whether in his many daring exploits on the battlefield or in his equally frequent acts of insubordination towards higher authority. It is remarkable that he got away with both almost scot-free, and he acknowledges that he owed much to ‘Leakey’s luck’.

Rea Leakey has always been thirsting for action and spoiling for a fight. The reader of these lively memoirs will relish his vivid descriptions of the many adventures he met with on his way up the military ladder from Subaltern in Egypt before the Second World War to Major General, responsible for British troops in Malta and Libya when they were about to leave both places in 1967.

Field Marshal Lord Carver GCB, CBE, DSO, MC1998

Introduction

As Lord Carver has indicated in his Foreword, Rea Leakey was one of that remarkable band of men who made up the Royal Tank Corps between the wars. Intelligent, capable, bursting with enthusiasm, they typified all that was best in the prewar British Army, yet constantly had to fight against the prejudice and crass stupidity of many senior officers in the War Office and elsewhere, who still saw the horse as the primary means of providing shock action on the battlefield. My favourite example of this, which I have to say I have quoted many times before, was the statement made by the then Secretary of State for War, Duff Cooper, when he introduced the Army Estimates for 1936, in which he apologised to the Cavalry for having to start mechanising eight of their regiments, saying, ‘It is like asking a great musical performer to throw away his violin and devote himself in future to the gramophone.’ Many brave men who then had to fight in obsolete, under-armoured and under-gunned light tanks would have to give their lives to make up for such ostrich-like idiocy that delayed mechanisation.

Some of the wartime adventures of Major General Arundel Rea Leakey, CB, DSO, MC and Bar, Czech MC, have in fact appeared in print on a number of occasions before this book. For example, his devastating raid on Martuba Airfield during Wavell’s campaign when he destroyed all the Italian aircraft and his subsequent actions in Tobruk, both of which earned him Military Crosses, were briefly recounted in David Masters’ wartime best seller of 1943, With Pennants Flying, subtitled: The Immortal deeds of the Royal Armoured Corps. Later, one of his exploits with the Australians in Tobruk in August 1941 was featured in picture script format on the front and back covers of the Victor magazine, in July 1969, while I used yet another of his battles in my book, Tank Action, to illustrate the bravery of British tank crews, fighting in their paper-thin A9s against much superior German PzKpfw IIIs and IVs. This, however, is the first time all his wartime service has been fully documented. His autobiography actually includes the postwar years as well, but space has prevented us going any farther than the end of 1945, except in brief summary.

My first meeting with General Rea was as a member of Intake 1 at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, when it reopened after the war between 1946 and 1947. He was my company commander in Dettingen Company, Old College, and one of the main reasons why, in July 1948, I was commissioned into the 1st Royal Tank Regiment. Our paths naturally continued to cross and when I attended the Staff College, Camberley, in 1959, I discovered to my great good fortune that he was my college commander and, at the end of the course, he was instrumental in getting me my first staff appointment as GSO 2 at the Army Air Corps Centre at Middle Wallop. Sadly, neither of us knew that I was colour-blind, so the only thing I eventually flew – after some fairly hair-raising lessons in a Chipmunk – was a desk!

It has been both an honour and a great delight for me to be permitted to edit General Rea’s memoirs. I did a similar job some years ago with Sgt Jake Wardrop’s diary in my book, Tanks Across the Desert. Jake was a tank driver, then a Sergeant tank commander in 5 RTR, which General Rea later commanded. Jake was another of the wonderful breed of tank soldier who went so bravely into battle in 1939, their esprit de corps and fighting ability more than making up for the gross imperfections in their equipment. Sadly, he was one of those who did not survive to share with us the postwar years. As I did with his memoirs, I have tried again to explain a little of the background to the period covered by each of Rea’s chapters, without being too obtrusive. I trust the reader will find my remarks of interest and valuable – but of course if they are superfluous then please ignore them!

After thirty-two years of active soldiering with the RTR, in which I served with the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 7th and 42nd RTR, followed by thirteen years of ‘part-time’ soldiering running the Tank Museum (where I finished up with almost more tanks than the entire British Army!), and now after a further five years editing the regimental journal, Tank, I believe I know my regiment fairly well, certainly well enough to be able to say with conviction that every potential RTR officer should read, mark, learn and inwardly digest General Rea’s remarkable memoirs and then try to emulate his fighting spirit in their careers – and at the same time of course endeavour to have just as much fun and excitement as he clearly did: FEAR NAUGHT!

George FortyBryantspuddle, Dorset1998

Postscripts

Sadly, Major General Rea Leakey, like so many other brave Tank Corps, Royal Tank Corps and Royal Tank Regiment soldiers has, in the words of the regiment’s unofficial motto – which is an apt interpretation of the Regimental Colours of Brown, Red and Green – now passed on, ‘From the Mud, through the Blood to the Green Fields Beyond’. However, he fortunately did live to see the first edition of his autobiography published, though not long enough to see his younger son David, also an RTR officer, become Regimental Colonel Commandant, reach the rank of Lieutenant General and later become Black Rod.

Lieutenant Colonel George Forty OBE, the editor of General Rea’s wartime diary, passed away in 2016. An acclaimed author of over sixty military history books, including The British Army Handbook (1998), Forty joined the British Army in 1945 and served in the Royal Tank Regiment for thirty-two years. After retiring from the Army, he became director of the Tank Museum in 1981 and greatly expanded its collection. He was made a fellow of the Museums Association in 1993 and was awarded the OBE in 1994.

ONE

Born in Kenya

Editor: In this opening chapter, Rea Leakey gives a vivid impression of growing up in Kenya, his father literally having to carve out a home for his family from the virgin bush with his bare hands. Leakey Snr must have been one of the Allied troops who fought against the redoubtable Col (later Gen) Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. He was a determined and resourceful German guerrilla leader who had hoped to influence the war in Europe by pinning down a disproportionately large number of Allied troops in the area, which had been German East Africa (Deutsch-Ostafrika) and later became included in what is now Kenya. He finally surrendered twelve days after the Armistice and returned to Germany a hero. Kenya was established as a British Protectorate in 1920 (British East Africa) with the British East Africa Company holding commercial control. This remained the situation until just after the Second World War.

Like the children of so many colonial families, Rea was forced by his circumstances to come back to England to complete his education and, as he explains, this led to him becoming a GC (Gentleman Cadet) at the Royal Military College – ‘the little hell over the hill’ as it was called by the then Master of Wellington College, which was situated a few miles away! Over 50 per cent of the GCs were the sons of Army officers (hence normally penniless). The remainder were sons of members of the ICS (Indian Civil Service) or more rarely of the liberal professions. Few – under 5 per cent – had not been to one of the recognised public schools. Fees were considerable, although there were scholarships to be won, which were awarded from the funds of disbanded Irish regiments. The RMC had the typical outlook of most of the British Army between the wars, as one historian later explained: ‘Sandhurst remained throughout the years between the wars an isolated military encampment in a chiefly anti-military Britain (with a traditional class background), there was no sign of the radical changes that were shortly to transform the character of war … The entire emphasis, indeed, of military recollection after the First World War dwelt on those battles where the tactics had been perhaps fumbling or even non-existent but where the casualties had been heaviest – not on those conflicts technically of great interest.’1

When Rea arrived at Sandhurst the RMC was comprised of four companies of cadets (numbered 1, 2, 3 and 5), divided between the Old and New Buildings. Each company contained a mixture of GCs. At the top, there were the Senior Cadets, some of whom were Under Officers and Sergeants; then came the Intermediate Cadets, some of whom were Corporals and Lance Corporals; finally, there were the newly joined Juniors – the lowest of the low. It was a tough place as Rea would discover, with much of the discipline left to the cadets themselves. This was justified by the fact that the staff considered that they were not running a kindergarten but rather training young men for the dirty business of fighting, so they did not intend to ‘snoop around seeing whether the cadets treat one another like Little Lord Fauntleroys’, as one source put it, and worked on the principle that ‘a man’s contemporaries are his fairest judges’. Their reasoning for this ‘hands-off’ approach was that a wild young man could learn wisdom when he grew older (if he survived!) but that a spiritless young man could not learn the dash that wins battles.

Rea Leakey: On 30 December 1915, I was born in Nairobi. My father was a farmer, and like many other white farmers he joined the British Army, which drove the Germans out of Tanganyika. It was not an easy task, if only because of the lack of transport – mostly black people carrying supplies through the bush. Because my father spoke Swahili and Kikuyu, he recruited and looked after these stalwarts, many of whom died of malaria. My father survived several bouts of this disease and was finally invalided out of the Army mainly because he was very deaf.

In 1920, Dad bought a soldier-settler’s farm north of Rumuruti, some 150 miles from Nairobi, and in due course the family set forth to this very large stretch of land inhabited by a variety of wild animals. Our transport consisted of three wagons, each drawn by sixteen oxen, and the journey lasted three months. Our mother, née Elizabeth Laing, was some ten years older than my father, of a tough Scots family. Her father was also a farmer. By this time she had produced four children: Nigel, Robert, Rea (me) and Agnes. She was a very brave and competent woman, and for much of the journey was in charge because Dad was ahead with a team of workmen building bridges, then our house and the thorn-tree bomas (barricades) for the cattle.

Rumuruti was, and still is, a small township – in those days an Indian duka (shop) and a few farmers. Our farm was some 30 miles north in the middle of nowhere. Well do I remember the house that Dad built – mud floor and grass thatch for the roof. Mother hated cats (her sister, Alice, A.A. – Aunt Alice, was allergic to them) but had to tolerate them because they dealt with the rats, helped by snakes. The latter were numerous and mainly lived in the roof. However, one breed of snakes, the puff-adder, enjoyed the comfort of our bedrooms. They are killers, and when we went to bed with a candle, a pussy-cat was pushed into the room to check if Mr Puff-adder was at home. If he was Pussy growled, Dad was alerted and he dealt with the snake.

As children, we could not have had a better life. Dad was one of the most honest and straight men I have ever known. The Africans called him Morrogaru – the Kikuyu for tall and straight. Our mother was equally loved by all of us – black and white. She was a good teacher and nurse; young as we were, our parents taught us the three Rs and a great deal about the birds and beasts that surrounded us. Nigel and Robert were taught to ride, and they enjoyed the task of chasing the numerous ostriches off the crops of maize.

Quite often at night our parents would wake us up to watch herds of zebra being chased by lions past our house and other buildings. Then we would hear the kill and go back to bed. It was not long before the pride of lions in whose territory we lived decided it was easier to jump into the cattle boma and come out with a bullock instead of chasing zebra. Dad discovered their den, a large cave some 10 miles from our house, and this was where they would take their afternoon siesta. They had to be destroyed because there was no other way to stop them devouring the cattle.

Each parent had a twelve-bore shotgun and they were the only ones on the farm who knew how to shoot. They went to the cave and sent the dogs in to entice the lions out of their den. Out came five angry beasts. Dad shot the first two, Mum got the next two, and Dad had time to reload and kill the very angry leader of the pride. All of us – staff and family – fed on meat, home-grown vegetables and ground maize (posho in Kikuyu). Twice a week Dad saddled his horse and rode out into the veldt and came back with a gazelle or bushbuck. He hated killing animals, but we had to be fed.

Then the rains failed and the river began to dry up. A well was dug, but there was little water, nothing like enough for the cattle. Finally the remaining large pool in the river began to take the toll and it had several dead hippos in it. There was only one answer – pack up, sell the livestock for a pittance and find another job. We traced our steps back to the small town Nyeri, 100 miles from Nairobi. The White Rhino Hotel needed a manager, and this was our next home for a year. My parents disliked the work, especially running the bar, as they were teetotallers.

The next move was to a coffee farm at Ngong, 15 miles from Nairobi. It belonged to Bill Usher – a member of another branch of the Laing family. Mother ran this farm because Bill had other interests. Dad got a job running another farm at Machakos, 30 miles from Ngong. So we did not see much of him. When I was just eight years old, Mother was taken to hospital with a burst appendix and she died. Dad left his job and took over the Usher farm. He could not look after four youngsters. Fortunately the Leakey family came to the rescue and paid for Nigel and Agnes to be sent to England, where they were looked after by uncles and aunts.

Robert and I were sent to the Nairobi School as boarders, and who paid our fees I know not. It was a very tough school, and we boarders were not given much food. Most were day boys and their parents fed them. We soon learned to fend for ourselves; pigeons were plentiful, and it was not too difficult to kill them with a catapult. Fruit was difficult to obtain, but the Arboretum was some 4 miles from the school; there was a small plantation of oranges. Robert and I would frequently get out of bed just before dawn and, each armed with a pillowcase, we would come back with a good supply of fruit.

Unfortunately the staff who looked after the Arboretum discovered the thieves and a team of stalwart Africans were detailed to catch us. Thus it was that when we were gathering oranges, they gave a whoop of joy and went for us. We were off like a pair of scalded cats and escaped into a river that was wide, not deep, and abundant with bulrushes. In due course a team of about thirty Africans set out to find us. We eluded them by holding our noses and remaining under water until they had passed by. It was about 10 a.m. before we dared to sneak out and head back to school. The Headmaster – Captain B.W.L. Nicholson, RN Retired – was waiting for us. Two bedraggled Leakeys received six of the best, and it was a rhinoceros whip. Of course, we were little heroes because the weals were red and bleeding! Such was life at Nairobi School, which changed its name to the Prince of Wales School some years later.

Dad got married again – Bessie or Bully. She was a highly qualified teacher, and neither of us were fond of her, but she did teach us during our holidays, and by this time we had moved to Kiganju, close to Nyeri, where my father had exchanged his Rumuruti farm for one of the most beautiful 1,000 acres of land in Africa. Two rivers, the Thego and Nairobi, flowed down from Mount Kenya, and the farm lay between them. Once again Dad built a house, sheds, and huts for our Kikuyu labourers.

He built a road from Kigenju railway station down the steep forest-covered slope to the Nairobi River, then a bridge, and up to the other side to the farm buildings. He and his labourers completed this task using picks, shovels and axes – no such machinery as one would have even in Nairobi. His next task was to clear some 40 acres of forest and plant coffee bushes and build the sheds where the coffee beans were washed and dried. Then he bought tractors and ploughs, and planted 100 acres of wheat. But Leakey’s luck was not on his side. One afternoon I saw a single cloud heading towards the farm and called Dad’s attention to it. ‘Locusts!’ he shouted, and every labourer was sent to the wheatfield armed with empty fuel cans that they beat, in the hope that this would scare them off.

Three hours later the locusts had devoured every wheat plant and they then repaired into the forest. The next morning they moved on and left a devastating sight; such was their weight that most of the trees were stripped of their branches. So much for the wrath of the locusts. But one of the labourers was from a Wanderobo tribe, and locusts were his caviare. So thick were the locusts on the wheatfield that he had no difficulty in stuffing his mouth with them, and when he could eat no more he filled posho sacks, and that was his food for weeks.

The next disaster was the coffee: the soil, the climate, and the crop were superb, but the market had dropped. Brazil and other countries were burning their beans and Kenya followed suit. Dad then tried cattle, but that, too, was a disaster. In those days they were rare creatures, and they died of diseases, which were then unknown to the vets. This time the Laing family came to the rescue of Dad’s remaining children. Robert and I were sent to Mombasa where we embarked on a German ship named Ubena. We had never seen a ship or the sea, and two lads aged fourteen and twelve savoured good food, and plenty of it, on the two-month journey to England.

On a cold winter’s evening we arrived at Chichele Cottage, Oxted, Surrey. This was the home of our aunt Alice Laing (A.A.), a spinster who adopted us, and we loved her. Somehow she found the money for us to be educated at Weymouth College – a small public school for boarders and a few day boys. Our educational standard was very low and we were only accepted because Louis and Douglas Leakey, Dad’s cousins, had been taught by Mother in Kenya before she was married, and they were scholars who went on to Cambridge University when they left Weymouth.

We were soon in trouble because we went into Evening Chapel not wearing ties; but in Kenya we never wore such items, and, bless her, A.A. had forgotten to teach us how to tie a tie. Our first term at that school was hell, if only because we were bottom of the class and cold baths every morning were compulsory. At the age of sixteen Robert left school and trained as an aeronautical engineer. I left aged seventeen because A.A. had no more money, so I got a job as a farm labourer, employed by a Laing cousin, Joan Little, who was the first woman to get an agricultural degree at Reading University. She lived with her mother, bred large black pigs and a herd of Guernsey cows.

A.A. was in touch with the senior partner of a firm of quantity surveyors in London, and he agreed to accept me as an articled pupil (being paid a pittance) for a five-year course. So I left Joan’s farm with much regret, stayed at Chichele Cottage, and in due course went to London to meet the boss and find somewhere to live. The day before I was due to join this firm I decided that living in digs in the slums of London, working at night as a barman, was not for me. A.A. was out shopping, so I borrowed her phone and told the boss that he could find someone else as a pupil. He was not best pleased. Nor was A.A. when I told her what I had done; for the first and last time she was angry, and I don’t blame her. ‘So what are you going to do?’ she asked.

‘Join the Army – if they will accept me,’ I replied, and off I went to the Oxted Police Station.

The Police Sergeant examined me and produced the document for me to sign on as a Private in the East Surrey Infantry Regiment. Just before I signed up he said. ‘You speak good, you are very fit, and I think you might do better by taking an examination to become an officer.’ I accepted his advice, and he told me I had two months to go to a crammer and work up for the next examination in London, which then accepted candidates for special entry as officers in the Navy, Air Force, Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Applicants could apply to join any of the Services, and those who did best invariably went to the Navy, the next to the Air Force, then Woolwich where their best went to the Royal Engineers and the remainder became Gunners or Signallers.

Sandhurst accepted the remnants – wealthy Etonians, Harrovians and the like, who followed in their fathers’ footsteps and were commissioned into the Brigade of Guards and the Cavalry. Their academic ability mattered little but they had to be wealthy. I wanted to try for the Navy and secondly the Air Force. When I filled in the form A.A. insisted that I apply for Sandhurst because she was sure only Sandhurst would accept duffers like me. For two months I worked like the proverbial slave, cycling 20 miles to the crammer, returning in the evening, and then paying for my keep employed as a labourer.

The results of the examination were published by The Times in August. A.A. had very kindly paid for Robert, Agnes and me to join her for a holiday in Germany. So well do I remember leaving early in the morning to buy The Times, a two-hour walk to Bonn. Sure enough there was the long list of those who had passed the exam. It was in order of merit and naturally I started at the bottom of the list looking for my name. After scanning through at least four hundred names, I gave up, walked back to our hotel, threw The Times on the table and said to A.A. ‘That’s it, I must go back to Oxted and sign up as a private soldier – I have failed.’ I went out and walked for many miles, returning late at night, tired and very hungry. A.A. was waiting for me; she took me in her arms and said, ‘You stupid fool, why did you not start looking for your name at the top of the list – you are top of the list – and you could have gone into the Navy, Air Force, Engineers or Artillery!’ By God, I loved her.

However, there was a problem. The course at Sandhurst was eighteen months and the cost was £500, excluding payment for the servant who made your bed and cleaned the room. Uncle George (A.A.’s brother) came to the rescue and agreed to lend me £500 – a lot of money in 1934. This time Leakey’s luck was on my side. Because I passed in top, I was awarded a scholarship that covered all my costs – except the servant’s tip; that I earned by working on Joan Little’s farm during holidays. Sandhurst was tough – certainly for the first six months when you were a Junior and not only under the control of the Guards Regimental Sergeant Major, but also the Cadet Seniors; they were doing their last six months and, according to their ability, they held ranks from Senior Under Officer, Junior Under Officer, Sergeant and Corporal.

If a Junior misbehaved – late on parade or whatever – the four Senior Cadets gave him a ‘puttee parade’. After supper the criminal rushed up to his room, changed out of his officers’ mess dress into full combat uniform – boots, puttees, plus-fours, jacket and tie, Sam-Browne, scabbard and bayonet, and, last but not least, his .303 rifle. He would then rush downstairs and on to the parade ground. The four Seniors armed with torches, drilled him, each shouting a different command: about turn – slope arms – present arms – double – and on and on until the victim finally collapsed. His junior companions then rushed out and carried him upstairs, undressed him and put him under a shower, and so to bed. If a Junior tried to ‘beat the system’ and accepted two puttee parades, on the second night his tormentors were more brutal and the cadet ended up in hospital. One cadet tried to withstand a third successive puttee parade. He died.

After the first four months the two most promising Juniors were promoted to Lance Corporal, and normally one of the two would hold the rank of Senior Under Officer and had a very good chance of winning the Sword of Honour. Unfortunately I blotted my copybook. One of the Juniors was a wealthy polo player and he owned two very good polo ponies. An Intermediate Irishman told this Junior that he was going to ride these horses. This caused trouble and the Irishman got his way by using his whip. The Juniors ganged up and warned the Intermediates that the tormentor would be punished by them. They retaliated by providing an escort of four of their cadets armed with rifles and fixed bayonets. On a Saturday evening, when most of the cadets went to London or home, some of the Juniors spotted the Irishman going for a walk with his escort. Among others, I joined the gang who went after him. We stripped him, tarred and feathered him and threw him in a lake.

As a Lance Corporal I was dubbed the leader of the gang and the Senior Under Officers court-martialled me. I was found guilty, suffered two puttee parades, and lost my rank. However, at the end of the day I passed out of Sandhurst as an officer and received a second scholarship. I finished third in the Order of Merit – £50 a year for five years.

The Passing Out Parade at Sandhurst was and still is a great occasion, not only for the cadets but also for parents and girlfriends. Bless her heart, A.A. came to see me march up the steps of the Old Building, followed by the assistant adjutant riding his horse; she was my parent and my ‘girlfriend’.

Notes

1 The Story of Sandhurst, Hugh Thomas (Hutchinson, 1961).

Two

The Western Desert

Editor: On commissioning (on 30 January 1936 – so he was just 21), Rea Leakey would spend his first six months at the RTC Training Centre and Depot in Dorset, attending his Young Officers’ Course and learning the basics of tanks and tank warfare. By the mid-1930s mechanisation was gathering momentum, although Britain still lagged far behind other European armies. For example, the Army Estimates for 1936 included only £2 million in total for mechanisation and most of that was to be spent on lorries for the infantry. Brig (later Maj Gen) Percy Hobart, then commander of the 1st (and only) Tank Brigade, wrote in his annual report in 1936: ‘The Royal Tank Corps has now completely lost the lead in the matter of numbers and up-to-date equipment – and now retains superiority, if at all, only in maintenance, organization and tactical methods; and personnel. As to numbers, during these last three years our potential enemies have increased enormously their tank corps. In the RTC no such increase has taken place.’ However, despite this gloomy situation, there was a great deal for an enthusiastic young officer to do, within the scope of the RTC, which had six regular tank battalions and numerous independent armoured car/light tank companies, spread over the world in the UK, Egypt and India. As Hobart mentioned in his report, the high standard of efficiency within the RTC gave everyone a tremendous feeling of pride and esprit de corps, which undoubtedly made up for the daily problems of having to soldier in ‘clapped-out’ tanks.

After a few enjoyable months with 4 RTC in North Yorkshire, Rea would find himself on a troopship, bound for Egypt to join 1 RTC, then commanded by Lt Col (later Brig) J.A.L. Caunter. Nicknamed ‘Blood’, he was a splendid CO of great energy and imagination, constantly encouraging his young officers to get out into the desert, so as to learn the hard way how to live and navigate in some of the most inhospitable conditions on the planet. Like so many other British soldiers who lived and fought there, Rea Leakey clearly found a strange fascination in the barren landscape of the ‘Blue’ as the soldiers who fought there called it. The world famous explorer of deserts, Wilfred Thesiger, once wrote that no man could live in the desert and not come out unchanged, carrying with him, however faint, ‘the imprint of the desert, the brand that marks the nomad; and he will have within him a yearning to return, weak or insistent according to his nature. For this cruel land can cast a spell which no temperate clime can match.’1

In 1938, the year of the Munich Agreement, Percy Hobart, now a Major General, was flown out from England with orders to create an armoured division in Egypt. The enormity of his task can be judged by the fact that the only sizeable British force at his disposal was the Cairo Cavalry Brigade, whose equipment was prehistoric! It is, therefore, all the more remarkable that he managed to lay the foundations of one of Great Britain’s most famous armoured divisions – the 7th Armoured Division, the ‘Desert Rats’. Just before he arrived the Cairo Brigade was sent hurriedly to Mersa Matruh, to form the ‘Mersa Matruh Mobile Force’ (also known somewhat unkindly as the ‘Immobile Farce’!), which was then composed of the following: HQ Cairo Brigade and Signals; 3rd Regiment, RHA, equipped with 3.7in howitzers towed by ‘Dragons’ (an early type of tracked gun tower); 7th Queen’s Own Hussars, with two squadrons of light tanks varying in Marks from III to VIb, but with no ammunition for their heavy machine guns; 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars with old Ford 15cwt pick-up trucks, mounting Vickers-Berthier guns; 11th Hussars with 1924 pattern Rolls-Royce armoured cars and a few slightly more modern Morrises; 1 RTC, newly arrived from England, complete with fifty-eight light tanks (Lt Mk VIbs), but with worn-out tracks and few new ones available to replace them; 5 Company, RASC; 2/3 Field Ambulance, RAMC. Left behind in Cairo was the 6 RTC, equipped with a mixture of some old Vickers medium tanks and some light tanks of the same vintage as 7H.

After a few exercises around Matruh, the force returned to Cairo, where it was joined by their first infantry unit – the 1st Battalion, KRRC, newly arrived from Burma.

Rea Leakey: The next six months were spent at the Tank Corps Schools, Bovington and Lulworth, and for the first time in my life, I was solvent and able to buy a bull-nosed Morris for the large sum of £3. Eighteen months later, when I was sent abroad, I sold it to Robert for £5. It never let us down.

Then I was posted to the 4th Battalion, Royal Tank Corps at Catterick, North Yorkshire. We lived in wooden huts – no central heating, but a few coal-burning stoves. It was, and still is, an open and beautiful part of England. Sadly, we were then moved to Aldershot – not as pleasant, but for me it was near the Laing family and my Uncle George, who lived in Limpsfield, close to Chichele Cottage. He had several horses and hunted with the Old Surrey and Burstow hounds.

About 40 per cent of our time at Sandhurst was spent learning to ride a horse, and, indeed, even in 1963 an officer joining a cavalry regiment was expected to have his own horse and play polo. I was one of the few Tank Corps officers who had access to riding – Uncle George always lent me one of his horses, and I hunted with him. At the end of the hunting season the hunting fraternity organised amateur point-to-point races and they were very popular. One of Uncle George’s horses, Grasshopper, was a very good steeplechaser but had never been entered for a race. As I was young, light and a good rider, my uncle entered me for the amateur Old Surrey and Burstow Races.

I spent most weekends training Grasshopper, staying with my Laing relations and thoroughly enjoying life, but always money was scarce so girlfriends were not interested in me. However, Uncle George’s two daughters were most attractive, and, although older than me, they were great companions. Five days before the point-to-point race I was told that I was to board a troopship at Southampton and set sail for Egypt on the day of the race. This was a great disappointment and the one and only chance I had of riding in a race. However, Uncle George rode Grasshopper on the day and he finished second. He wrote and told me that I would have won with ease, and both of us would have taken the bookies to the cleaners because Grasshopper was a rank outsider. As it was, he did very well – God bless him!

That was in March 1938, and three weeks later the troopship entered Alexandria harbour. I was now one of thirteen young officers in the lst Battalion Royal Tank Corps. We moved into tented accommodation adjoining a British barracks at Helmeih, some 10 miles outside Cairo, and our outlook was the desert. This was to be our uncomfortable home for the next eighteen months. However, the pay was good, the sports facilities were excellent, and, above all, there was the Gezira Club in the heart of Cairo. This was where we met many of the British residents who welcomed us to their homes. Inter-regimental sports were highly competitive, and I soon found myself involved in most of them – athletics, rugger, cross-country (desert) running, cricket and boxing.

On two occasions brother officers entered me for individual open competitions without my knowing, and only told me when the entrants were published, and certainly, on the first occasion, I did not withdraw my name. I was entered for the Army of Egypt boxing competitions fighting middleweight, and one of the entrants was my batman. I fought my way to the finals, and the arena was packed with soldiers. The fight of the evening was the middleweight, 2/Lt Leakey versus Pte Tyler, and, for all to see, written up, his batman. To the delight of the crowd, he won. When he woke me up the next morning with a cup of tea he took a good look at my face, gave me a mirror, and with a grin, said, ‘Sorry, sir’. I had two black eyes and a broken nose. What neither of us knew was that I had broken a small bone (the scaphoid) in my wrist for the second time. It never healed and ended my boxing career.

The second occasion was not as bad. I was entered for the Egyptian tennis tournament – in those days more or less the run-up to Wimbledon. I was entered for the Men’s Open Singles, and by chance I did see the entry in the local papers. Why not, I said to myself – at least I could boast about my inevitable defeat in that I was the only Army entrant. I got through the first two rounds – how, I know not, except that I had a good first service and it worked well for a change.

The next day I was summoned before our CO – Blood Caunter. ‘You are playing too many games and overdoing it. Tennis has nothing to do with regimental sports, so you will give that up for a start,’ he said.

‘But, sir, tomorrow I am playing in the third round of the Men’s Singles in the run-up for Wimbledon, and my opponent is the well-known German – von Cramm.’

His reply was final. ‘I could not care who you were playing against. You will give up tennis.’ I still boast about it.

It was most unusual to see an officer dressed in uniform in the Gezira Club, and here was Derek Thom marching into the lounge. He was doing a week’s Orderly Officer for some minor crime. ‘Back to camp at once and tell any others you see here,’ he said. Nobody took much notice – he had pulled our legs too often. I had been asked out to dinner, and my host’s daughter was most attractive. But that was one date I never kept. This was in 1938, and Chamberlain had gone to Munich to meet Hitler, and even in distant Cairo the clouds of war loomed heavy.

Just twenty-four hours after we had left the Gezira Club we were moving out of Cairo in a train bound for Mersa Matruh, a small harbour town some 100 miles west of Alexandria. Our tanks were unloaded, and we moved out into the desert to await the expected attack by the vast Italian Army based in Libya. But Chamberlain succeeded in putting off the war for a year. There are a few who relish the thought of war, and we were no exception, but we were no conscript army. We were proud of our tanks and felt that we could hold our own against our potential foes. Yet there were no grumbles when we were told that we should return to Cairo in three months’ time for Christmas.

Our time at Matruh was not wasted. Almost every day parties used to go out on reconnaissance, finding out where the going was good, plotting in each fold in the ground and, above all, learning to navigate. Once away from the sea, there are very few landmarks, no roads or railways that can be used to plot one’s position. Each unit had its expert navigator whose task it was to ensure that he could give a map reference of his position whenever asked. He plotted a course as would a mariner and steered his vehicle on that bearing with the aid of a sun compass and noting the distance measured by his speedometer. On his wireless aerial he flew a large black flag. At the end of a 50-mile trip across the desert it was not considered bad if he finished up 2 miles from his destination, but more often than not his destination would be a mere map reference and nobody could dispute his accuracy. There was no quick method of fixing an exact point on a featureless desert.

I did my first long desert trip about a month after my arrival in Cairo. We were fortunate in having Capt Teddy Mitford as a member of the regiment; he was one of a band of prewar officers who explored the desert for the love of it, and later were to form the famous Long Range Desert Group. Under his expert guidance we learned not only to navigate but, almost as important, how to tell at a glance which bit of the desert would provide good hard-going, and so avoid a soft patch where vehicles would sink in up to their axles.

By the time we left Matruh and returned to Cairo, every officer and many of the NCOs could navigate across any stretch of desert by night or day with complete confidence. I was fortunate in being chosen as one of two young officers whose duty it was to run navigation courses for our own and other regiments; the other officer was Peter Page, who, like me, had learnt to love the desert.

On our return to Cairo, Page and I probably spent more days in the desert than in barracks. We would leave Cairo with about fifteen heavily laden lorries and disappear into the desert. Nobody worried where we went, and from the time we left the Giza Pyramids until we returned, perhaps six weeks later, we were completely out of touch with the outside world. Only when we visited the few oases, which lie several hundred miles to the south-west of the Nile Delta, did we see other human beings. Whenever possible I used to try and call in on a small oasis called Qara.

It was a difficult place to reach, as on one side the country is very broken, and on the other stretches the Sand Sea, which to this day is almost impassable to two-wheel drive vehicles. The sight of this small patch of vivid green, when the last ridge was crossed, was always more than welcome after crossing many weary miles of waterless waste; but even more welcome was the fresh clean water bubbling up out of the ground, and the shade of the date palms. The inhabitants, who numbered about a thousand, lived in caves burrowed into an enormous rock that stood by itself to one side of the oasis. The Sheikh lived in the centre, like a queen bee in a hive, and he was always glad to see me. I spoke Arabic quite well and he liked to hear what was going on in the outside world. I usually brought him some small present and he always insisted on my staying for a special meal – a whole sheep served up on a large copper dish and heaped around with rice in rancid butter. We sat round it on our haunches and pulled chunks off with our hands. But how I dreaded being given the titbit – a sheep’s eye! At the conclusion of the meal, it was polite to let off a resounding belch, and the Sheikh always liked Page, because he had the art of producing a monster.

Only once did I get into serious trouble on these long journeys into the desert, and then it was nearly disastrous. I used to read every book I could find on the Western Desert of Egypt, and in one an explorer described a particularly interesting journey he had made by camel across the Qattara Depression and along a secret route that led up the steep escarpment to the west of it. This depression forms a natural obstacle to vehicles, stretching from its northern point 40 miles south of the Mediterranean Sea at El Alamein to the oasis of Siwa, which lies some 200 miles south of Mersa Matruh.

In those days the maps we had gave little detail of the topography of this part of North Africa. To the north was the Mediterranean and to the south the location of the various oases were shown, but little else. So it was not easy to plot the explorer’s exact route that led across the depression to the way up the escarpment allegedly impassable to camels – let alone two-wheel drive vehicles. No doubt it had been used by raiding parties and perhaps as a slave-trade route. In June 1939, Page and I, with some thirty soldiers, set out to find it.

The journey from the Pyramids to the depression was not difficult, but inevitably some inexperienced drivers would get bogged down in the sand, and time would be lost laying down sand-mats to move the two-wheeled drive lorries out of a soft sandbed. Then began the search to find the camel track, and on the second day we found it – at least there were skeletons at intervals leading towards the escarpment to the west of the depression, which we could see in the dim distance. Much of the way we had to go ahead of the column of vehicles on foot to pick a route across the soft sand, so progress was slow. A week after we had left Cairo we arrived at the foot of the escarpment. We climbed up to the top and on to what appeared to be the usual relatively flat desert stretching away to the west.

That night we leaguered up beneath the pass and decided that at dawn we would try to dig a way for vehicles up the escarpment. If we succeeded, then we calculated that we should have just enough petrol and water to enable us to reach the Mediterranean coast somewhere near Mersa Matruh. But if not, then we had no alternative – we must admit failure and retrace our steps. It took us two days hard digging but we got all fifteen vehicles to the top. It was hard hot work, and we were beginning to run short of water. So, another decision: turn back and hope that we had sufficient petrol to take us to Cairo – 300 miles – or head north for the coast – 150 miles. These were basic calculations because we had no way of knowing exactly where we were. Water could be rationed, and so we went north.

We now found ourselves travelling over a plateau and the going was good until we hit the next obstacle. This was the end of the plateau and there was a drop of some 50ft. We searched for a way down, but in vain. This was our twelfth day out, and the sun was sinking. We decided to stay where we were and take stock of our situation. We still had enough petrol to retrace our steps to Cairo – it might mean leaving some of the vehicles short of base. If we went down the escarpment we would not be able to get the vehicles back up, so we would have to go north towards the sea, no matter what further obstacles we met. We decided to go on.