18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

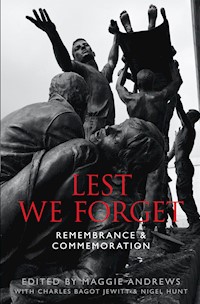

'Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.' These words, spoken at war memorials across the United Kingdom and around the world on 11 November every year, encapsulate how we commemorate our war dead. Lest We Forget looks at how we remember not only those who died in battle, but also those whose memory is important to us in other ways. This wide-ranging review considers such topics as Holocaust Memorial Day, the Hillsborough Disaster, memories of the Spanish Civil War, the genocide in Rwanda, Diana, Princess of Wales and the role of the Cenotaph and the National Memorial Arboretum. With an endorsement from The Royal British Legion, which celebrates its 90th anniversary in 2011, this is a timely study, and is relevant not only to people in the United Kingdom, but recognises the universal need to remember.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

LEST WE FORGET

LEST WE FORGET

REMEMBRANCE & COMMEMORATION

EDITED BY MAGGIE ANDREWS

WITH CHARLES BAGOT JEWITT & NIGEL HUNT

First published in 2011

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved © Maggie Andrews, Charles Bagot Jewitt & Nigel Hunt, 2011 © The contributors, 2011

The right of Maggie Andrews, Charles Bagot Jewitt & Nigel Hunt to be identified as the Editors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The right of the contributors to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7334 5MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7333 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

List of Contributors

Foreword

‘Lest We Forget’

Introduction

Unpicking Some Threads of Remembrance

Charles Bagot Jewitt

Contesting Cultures of Remembrance

One

Remembering the Dead, Forgiving the Enemy: The Royal Engineers & the Commemoration of the Second Boer War

Dr Peter Donaldson

Two

The Memorialisation of Gallipoli and the Dardanelles 1915: History & Meaning

Dr Bob Bushaway

Three

Unveiling Slavery Memorials in the UK

Nikki Spalding

Changing Cultures of Remembrance

Four

Public/Private Commemoration of the Falklands War: Mutually Exclusive or Joint Endeavours?

Karen Burnell & Rachel Jones

Five

Memorials and Instructional Monuments: Greenham Common & Upper Heyford

Daniel Scharf

Six

What Difference Can a Day Make?

Carly Whyborn

Seven

Commemorating Animals: Glorifying Humans? Remembering and Forgetting Animals in War Memorials

Dr Hilda Kean

Remembrance in Popular culture

Eight

Beneath the Mourning Veil: Mass Observation & the Death of Diana

James Thomas (introduced by Dorothy Sheridan)

Nine

Remembrance in Sport: A Case Study of Hillsborough

Dr Jamie Cleland

Ten

Between Ephemera and Posterity: The Commemorative Magazine Issue

Dr Fan Carter

Eleven

Web-Remembrance in a Confessional Media Culture

Dr Maggie Andrews

European Remembrance

Twelve

Pacifist War Memorials in Western France

Dr Jane Gledhill

Thirteen

Recuerdo la Guerra Civil España

: Turning Forgotten History into Current Memory

Dr Nigel Hunt

Fourteen

The Role of the

Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge

in Commemorating the Second World War

Gerd Knischewski

Fifteen

Remembering the Victims of Communism

Kristýna Bušková

Art, Design & Visual Cultures of Remembrance

Sixteen

Artists of Twentieth-Century Remembrance

Christine McCauley

Seventeen

Frank O. Salisbury 1874–1962: A Case Study in Practising Remembrance

Gill Thorn

Eighteen

Ambiguity, Evasion and Remembrance in British Crematoria

Professor Hilary J. Grainger

Nineteen

‘Subvertising’ as a Form of Anti-Commemoration

Professor Paul Gough

Regional sites of Remembrance

Twenty

The Maze/Long Kesh: Contested Heritage & Peace-Building in Northern Ireland

Dr M.K. Flynn

Twenty-one

Remembering the Fallen of the Great War in Open Spaces in the English Countryside

Professor Keith Grieves

Twenty-two

National, Local and Regimental: Commemorating Seven Fife Soldiers who Died in Iraq 2003–07

Dr Mark Imber

Twenty-three

Fates, Dates and Ages: An Investigation of the Language of War Memorials in Three Regions of Britain

Colin Walker

National Remembrance Events & Places

Twenty-four

The Cenotaph and the Spirit of Remembrance

Philip Wilson

Twenty-five

Meeting a Need? What Evidence Base Supports the Signifcant Growth in Popularity of the National Memorial Arboretum?

Charles Bagot Jewitt

Twenty-six

The Future of Remembrance is our Young People

Paula Kitching

Twenty-seven

‘The Journey’: A Unique Approach to Holocaust Education

Karen Van Coevorden

Women & Remembrance

Twenty-eight

Women’s Writing and the First World War

Dr Jane Gledhill

Twenty-nine

Suffrage, Spectacle and the Funeral of Emily Wilding Davison

Dr Maggie Andrews

Thirty

‘They took my husband, they took the money and just left me’: War Widows & Remembrance after the Second World War

Dr Janis Lomas

Thirty-one

Remembering Women: Envisioning More Inclusive War Remembrance in Twenty-First-Century Britain

Dr Debra Marshall

Memorials Across the world

Thirty-two

Stigmata of Stone: Monuments, Memorials & Markers in the US Landscape

Professor Susan-Mary Grant

Thirty-three

The Resistance Memorial, Bisesero, Rwanda

Dr Rachel Ibreck

Thirty-four

Constitution Hill, Johannesburg: Building Democracy on Remembrance

Dr Tony King

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Dr Maggie Andrews: Assistant Head (Undergraduate Programmes),Institute of Humanities and Creative Arts, University of Worcester

Commander Charles Bagot Jewitt: Chief Executive, National Memorial Arboretum, Alrewas, Staffordshire

Dr Karen Burnell: Research Associate, Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London

Dr Bob Bushaway: Former Director of Research and Enterprise Services and Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre for First World War Studies, University of Birmingham

Kristýna Bušková: Graduate student, Institute of Work, Health and Organisations, University of Nottingham

Dr Fan Carter: Principal Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies, Kingston University

Dr Jamie Cleland: Senior Lecturer in Sports Sociology, Staffordshire University

Dr Peter Donaldson: Lecturer in History, University of Kent

Dr M.K.Flynn: Senior Lecturer, International Politics, University of the West of England

Dr Jane Gledhill: Independent Scholar and Lecturer in Christian Spirituality, Sarum College

Professor Paul Gough: Pro Vice Chancellor and Executive Dean of the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of the West of England

Professor Hilary J. Grainger: Dean, London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London

Professor Susan-Mary Grant: Professor of American History, Newcastle University

Professor Keith Grieves: School of Education, Kingston University

Dr Nigel Hunt: Associate Professor in Psychology, Institute of Work, Health and Organisations, University of Nottingham

Dr Rachel Ibreck: Research Fellow, School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol

Dr Mark Imber: Senior Lecturer, School of International Relations, University of St Andrews

Rachel Jones: Graduate Student, Department of History, University of Southampton

Dr Hilda Kean: Director of Public History and Dean of Ruskin College, Oxford

Dr Tony King: Research Fellow, Department of Politics, University of the West of England

Paula Kitching: Freelance Historian and Education Consultant

Gerd Knischewski: Senior Lecturer, School of Languages and Area Studies, University of Portsmouth

Dr Janis Lomas: Independent Scholar

Dr Debra Marshall: Research Development Manager, University of Gloucestershire

Christine McCauley: Senior Lecturer in Illustration, University of Westminster

Daniel Scharf: Department of Continuing Education, University of Oxford

Professor Dorothy Sheridan: Mass Observation Project Director, University of Sussex

Nikki Spalding: Graduate Student, International Centre for Cultural and Heritage Studies, Newcastle University

Gill Thorn: Independent Scholar

Karen Van Coevorden: Primary Education and Training Officer, The Holocaust Centre, Laxton

Colin Walker: Senior Lecturer, Department of Post Compulsory Education and Training, University of Huddersfield

Carly Whyborn: Chief Executive Officer of the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust

Philip Wilson: County Chairman, The Royal British Legion, Warwickshire

Foreword

‘LEST WE FORGET’

Remembrance Sunday and Armistice Day ceremonies have, over the past decade, been growing once more in significance as public events; and war memorials remain a key element of the landscape of many of our cities, towns and villages. However, the forms and practices of commemoration change as society evolves. Elements of informality now feature in acts of remembrance which would have been unthinkable in earlier generations and private grief is more on display. There is a hugely increased role for broadcast and the internet. Museum exhibitions also are reflecting an increased interest in memory, pilgrimage and contemporary heritage; and memorials are being placed in new physical spaces, constructed from modern materials in ways that challenge and provoke.

Remembrance, in terms of acts of commemoration and memorialisation of those who have died in the service of their country, is thus a legitimate area for study and re-interpretation in the context of the UK and the modern world. All traditional assumptions about national identity, including remembrance, must be regularly re-examined in the context of our multicultural society and in an ever-changing political climate. We also need to be aware that most people in today’s diverse society have not shared the experience of national war beyond the popular representations in film and museums.

The Royal British Legion, now in its ninetieth year, is proud to act as the ‘National Custodian of Remembrance’ and will always maintain the focus for Remembrance Sunday and Armistice Day on the armed forces. However, The Royal British Legion is very much part of the changing world and seeks to keep the concept of remembrance strong and relevant to all. At the Legion’s year-round centre for remembrance, the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, not only are the fallen honoured, but also those who have served and suffered for the whole national community, including family members and comrades of the bereaved. Quiet pride, in no way jingoistic, is fostered in those who have given our country so much, and in so many ways.

In 2008, in this context, The Royal British Legion, the National Memorial Arboretum and the universities of Staffordshire and Nottingham set up a series of seminars to:

• deepen understanding of the meaning and significance of commemoration in the contemporary culture informed by a study of the practice of commemoration in other times and cultures

• inform the practice of commemoration and remembrance for future generations

• explore the relationship between remembrance, commemoration and the armed forces covenant

• stimulate further study of remembrance, commemoration and memorials

Drawing on an inter-disciplinary group of experts working in the fields of History and Heritage, International Relations and Politics, Psychology, Architecture, Human Geography, Media and the Creative Arts, the study of religions and teacher training alongside practitioners working for religious groups, in the armed forces, education, the Mass Observation Archive, The Royal British Legion and at the National Memorial Arboretum, the seminars have so far produced a website, a dedicated journal edition of War and conflict Studies and this volume.

The topics covered by the articles in the book are eclectic, and deliberately so, because only by reading widely around the subject can we understand developing trends and appreciate the rightful place of remembrance in our contemporary, globalised world. If you are interested in any of the many facets of remembrance, then I commend this book to you.

Lieutenant General Sir John Kiszely, KCB, MC National President, The Royal British Legion

The editors of this book would like to express their thanks to:

Professor Christine King, for inspiring the concept and all those who participated in the NMA Seminars on Remembrance Commemoration and Memorials; The Royal British Legion, especially John Farmer, National Chairman, Chris Simpkins, Director General, and Stuart Gendall, Director of Communications, for their support of the seminars and this book; Dave Faul for his technical expertise.

Introduction

UNPICKING SOME THREADS OF REMEMBRANCE

Charles Bagot Jewitt

How does traditional ‘Remembrance’ relate to core human emotions? Do the enormous number of memorials throughout Britain indicate that remembrance is part of the universality of the human spirit or are they a purely western cultural phenomenon? These were typical of the questions underlying our seminar discussions at the National Memorial Arboretum and at The Royal British Legion Head Office at Haig House in London. Not all questions could be answered but the multi-disciplinary approach adopted through our seminar series shed some interesting new light on the contrasting motivations for acts of remembrance and memorialisation. The threads explored will become more apparent as you read through the various articles in the volume.

State, or ‘top down’, motivation is the key driver in national remembrance. Many nation states wish to be seen as recognising their role in the loss of their individual citizens in conflict, and many governments play a part in a national commemoration and memorialisation process. In a British military context this can be viewed as the state fulfilling part of its ‘Military Covenant’ in formally recognising loss and grief. State memorials are often significant architectural structures, and their sites can be the focus for significant national commemorative events, such as Memorial Day and Veterans Day at Arlington National Cemetery in the USA, or Remembrance Sunday at the Cenotaph in London.

The Menin Gate at Ypres, Belgium, designed by Blomfield, and Thiepval Memorial in northern France, designed by Lutyens, are state-scale memorials which provide similar iconic recognition to the British missing of First World War battlefields. Other such memorials, including Vimy Ridge, Canada’s impressive memorial to the First World War in northern France, and indeed the Cenotaph, do not contain the names of those who are being commemorated. By contrast, the UK’s new Armed Forces Memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum lists nearly 16,000 names that have died on duty in the military service of the country since 1945 and is, arguably, becoming something of a contemporary shrine.

While state-sponsored sites and ceremonies are needed, they are clearly not enough and for many smaller communities comradeship driven from the heart of the community (or ‘bottom up’) is the motivation for acts of remembrance, and for both formal and informal memorialisation. The town and village war memorials placed in nearly every significant community of the United Kingdom after the First World War, and added to after the Second, are often kept up to date in the present time (see Chapter 22).These still provide a setting for acts of remembrance similar in form to the national events at the Cenotaph. However, unlike some state memorials, the inclusion of names is critical in representing people who were intimately known to their communities and whose loss has been keenly felt.

The vast growth of websites to individuals lost in Afghanistan, including Google Earth’s ‘map the fallen’ project which was created by a company engineer in his spare time, may be considered as another form of ‘bottom-up’ response to recognising the deaths of individuals in an increasingly global community. In very similar fashion, Anfield football stadium in Liverpool provided the setting for a huge but very informal outpouring of non-military grief after the Hillsborough Disaster in 1989 (see Chapter 9), and today the dead are commemorated by both a traditional memorial and an online section of the club’s website in the way of many contemporary deaths on the battlefield.

The Basra Memorial Wall is a contemporary example of how, from informal beginnings, comradeship memorials can quickly become formalised. Brass plaques started appearing in Basra from 2003 onwards where individual British and coalition soldiers fell, and an initiative from a Roman Catholic chaplain resulted in a wall being built outside their headquarters. The wall then became the icon for the British presence in Basra and a centrepiece for the formal British withdrawal ceremonies from the province, which were watched on television worldwide. After a campaign by parents of the deceased, the memorial was rebuilt in the National Memorial Arboretum and dedicated in a ceremony attended by the leaders of the three main British political parties in March 2010.

Many memorials become sites of pilgrimage, and often these are memorials placed on sites of relevance to specific conflicts or incidents (see Chapter 13). A substantial memorial can be an important feature of a preserved battlefield, such as at Waterloo where the dramatic Lion Mound overlooks the entire site; or at the site of a human catastrophe, such as at Ground Zero in New York. Some of the oldest memorials in the United Kingdom were both places of faith pilgrimages and served a commemorative function: Battle Abbey, which commemorates the Battle of Hastings in Sussex, was founded no later than 1070 and is thus almost certainly the earliest battlefield site memorial still in existence in the country. Another early example is the stunning Crecy memorial window in Gloucester cathedral, paid for by a knight after the famous battle in 1346. Large-scale military campaigns such as Gallipoli spawned a variety of battlefield memorials on the peninsula created for differing purposes (see Chapter 2) and also memorials far removed from the events, including at the National Memorial Arboretum where a memorial makes a valuable link to the Turkish battlefield and is a useful educational tool.

Recognition, particularly for those who feel that their contribution has been ‘hidden from history’, provides another motivation for commemoration. Memorials of recognition to particular groups often form the focus for ‘tribal’ gatherings. Arguably, acts of remembrance at such memorials thinly disguise the primary purpose of re-union and the memorials themselves usually do not contain names of the fallen, although they may contain listings of campaigns, military honours or mottos. Such memorials may even be placed by nation states in other countries, where the message ‘don’t forget us, we helped you’ is implicit. Striking artistic form can be an important component of such memorials, as in those of Australia, New Zealand and Canada now located in London’s parks, which celebrate the contribution of those countries to freedom in Britain in the World Wars. Not infrequently, such memorials may be dedicated many years after the events they commemorate; the London Australian Memorial was dedicated as late as 2003.

Similarly, the Polish Armed Forces Memorial, dedicated at the National Memorial Arboretum in 2009, was initiated by the children of combatants in the Second World War. It deliberately tells the story of their parents’ contribution to the British and Allied war effort in an attempt to ‘right the wrong’ when Polish servicemen were not allowed to take part on the victory parades for fear of antagonising Stalin’s Soviet Union. Another comradeship-inspired Polish War Memorial listing the names of the fallen has already existed for many years in Northolt, London. Many other memorials at the National Memorial Arboretum share similar motivational reasons and some have been dedicated by non-military organisations such as police, fire and ambulance services, or national charities with a reason for commemoration such as the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

Monuments put up by groups (or ‘tribes’) to remember specific individuals, perhaps especially to the ‘great and the good’, can be seen in a similar light. It may be argued that by placing a memorial to a leading individual, such as Admiral Lord Nelson after the Battle of Trafalgar or to Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park in London 2010, the ‘tribes’ are indulging in a celebrity culture or even creating a secular sainthood, where the individual is seen as the manifestation of the group. It may also be significant that those who have personal or close family associations with the honoured individual are gathering to themselves a sense of distinction by association. However, individual memorialisation should also be recognised as being as old as mankind and fundamental to the human condition, as a look at some of the amazing medieval tombs and chantry chapels in Britain’s ancient cathedrals and churches, where sometimes priests were paid to say mass for souls of the wealthy departed in ‘perpetuity’, quickly confirms.

The emotive nature of remembrance may lead to acts of remembrance and memorial sites becoming highly contentious. The Northern Ireland ‘marching season’ is an example of where acts of remembrance still have the capacity to inflame. Dr Flynn’s article on Long Kesh (see Chapter 20) shows how both Protestant and Catholic factions, both of which were represented in the prison population, now vie for their version of history to be immortalised on the site. Other memorials, designed for non-controversial purposes, such as to Sir Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris outside St Clement Danes in London, have found themselves becoming contested space because of the popular legacy, and in some eyes infamy, of the individual concerned. The memorial was subject to a protest by the Peace Pledge Union at its dedication by Her Majesty the Queen Mother in 1992.

Some memorials may be deeply political, by their construction setting out deliberately to contest a point or to drive forward an agenda, occasionally attracting wide media coverage. The Shot at Dawn Memorial in the National Memorial Arboretum, one of many memorials to perceived abuse, was put in place to press the case for a pardon for servicemen executed during the First World War. Pardon was eventually achieved by an amendment to the Armed Forces Act in August 2006, by which time the Daily Telegraph had run a photograph of the memorial across its front page. Similarly, the British Nuclear Test Veterans Memorial nearby almost invariably attracts media attention when acts of commemoration are held due to the contestation surrounding the effects on those who took part and their offspring. A resin edition of a statue called ‘The Abandoned Soldier’ by James Napier was raised in Trafalgar Square in May 2007 as part of a plan to draw the government’s attention to the plight of those suffering mental injury due to military service. The sculpture has still not been created in its final form, yet the concept alone has the capacity to draw press and political attention to the cause it represents.

Remembrance is full of contrasting motivations, and frequently many contradictions. Often, elements of acts of remembrance or memorialisation contain more than one of the elements described above. Much of the primary motivation to remember, of course, reflects humankind’s deep and universal desire for significance, possibly immortality, and this is true in every age and culture. However, remembrance as the concept we think about today, be it narrowly focused on the military or more widely focused on different segments of the population, is ultimately a reaction felt by ‘survivors’ whenever life is cut short, and for whatever reason. Often remembrance brings with it other deep feelings of shock, anger and grief, and attempts to harness these and make sense of Homo sapiens’ periodic inhumanity to his fellow creatures. The laudable desire is never to repeat the mistakes of the past, and to preserve the memory of the fallen ‘lest we forget’.

Contesting Cultures of Remembrance

USUALLY, a degree of consensus exists in the decision to site a memorial and in the formation of acts of commemoration. However, with the passage of time and reinterpretation of history, subsequent contestation of memorials and rituals which were at one time widely embraced can occur. This is demonstrated in chapters on commemoration of the Second Boer War and Gallipoli. That said, some cultures of remembrance have been deliberately fostered to provoke or to alter a narrative of history, often for political ends. This is exemplified by the chapter on slave memorials.

One

REMEMBERING THE DEAD, FORGIVING THE ENEMY:

THE ROYAL ENGINEERS & THE COMMEMORATION OF THE SECOND BOER WAR

Dr Peter Donaldson

The unveiling of the Royal Engineers’ memorial arch to the fallen of the Second Boer War at the corps’ headquarters at Brompton Barracks, Chatham, on 26 July 1905 was greeted with all the pomp and circumstance that one would expect of such an important national ritual in Edwardian England. With the king in attendance to perform the official dedication, the Chatham News vividly captured the sense of collective pride that singled the day out as a patriotic carnival: ‘Flags! Flags! Flags! Flags here, flags there, flags everywhere – nothing but flags of all colours, all sizes and all descriptions, the whole combining to make a bright display.’1

Yet such nationalistic unanimity masked the difficulties that the corps’ memorial committee had faced as it had attempted to construct a memory site in honour of the 431 Royal Engineers who had died in the war. Although the scheme had been instigated by no less a person than Lord Kitchener, himself a Royal Engineer and latterly commander-in-chief of the British forces in South Africa, the memory of the war and the nature of the proposal were sufficiently contentious to negate the deference that seniority would normally command.

In May 1902, Kitchener, who had been commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1871, had written to the commandant of the corps at Chatham, Sir T. Fraser, with the offer of ‘four bronze statues of Boers and four bas-reliefs for use in a war memorial to the fallen’.2 For good measure he had enclosed a detailed sketch of his proposal. Unsurprisingly, Fraser had been quick to accept the offer and a memorial committee meeting in October 1902, chaired by Sir Robert Harrison, the Inspector General of Fortifications, unanimously agreed to press ahead with the plan.