Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

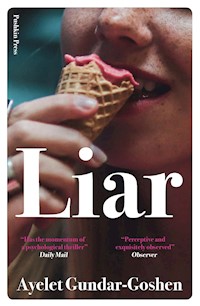

A delightfully outrageous novel about a sexual assault scandal by the internationally celebrated, prize-winning author of Waking Lions and One Night, Markovitch If being old meant making up things so you wouldn't be alone, then it really wasn't very different from being seventeen Nofar is just an average teenage girl - so average, she's almost invisible. Serving customers ice cream all summer long, she is desperate for some kind of escape. One afternoon, a terrible lie slips from her tongue. And suddenly everyone wants to talk to her: the press, her schoolmates, and the boy upstairs - the only one who knows the truth. Then Nofar meets Raymonde, an elderly woman whose best friend has just died. Raymonde keeps her friend alive the only way she knows how - by inhabiting her stories. But soon, Raymonde's lies take on a life of their own. A heart-stopping novel about deception and its consequences, Liar brilliantly explores how far a lie can travel - and how much we are willing to believe. Ayelet Gundar-Goshen is an award-winning novelist and clinical psychologist based in Israel. Her novels One Night, Markovitch and Waking Lions, both published by Pushkin Press, have been translated into 14 languages. She is an occasional correspondent for the BBC, TIME magazine and Israeli media.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 410

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Praise for Ayelet Gundar-Goshen

WAKING LIONS

‘Gundar-Goshen’s second novel twists and turns like a thriller, and it is particularly impressive in its moral ambiguities’

Sunday Times

‘The highly anticipated second novel [by Gundar-Goshen]… proves it’s not every day a writer like this comes our way’

Guardian

‘A classy, suspenseful tale of survival’

The Times

‘A literary thriller that is used as a vehicle to explore big moral issues. I loved everything about it’

Daily Mail

‘Brave and startling’

Financial Times

‘A complex and affecting moral thriller’

New Statesman

‘Exhilarating… a sophisticated and darkly ambitious novel’

New York Times

ONE NIGHT, MARKOVITCH

A Financial Times Book of the Year

‘A marvellous novel… What won me over from the first page is the exuberant generosity of Gundar-Goshen’s storytelling’

Financial Times

‘A lush debut… moving and satisfying’

Guardian

‘Sensual, passionate… A remarkable achievement’

TLS

‘Wry, ironically tinged and poignant’

Sunday Telegraph

‘Touching and funny… infused with a rich and telling irony’

Sunday Telegraph

‘A lively meditation on love and nationhood’

Independent

Contents

Liar

PART ONE

1

THOUGH IT WAS THE END OF SUMMER, the heat still waited outside front doors along with the morning newspaper, both boding ill. So sequestered in their air-conditioned homes were the people of the city that, when it came time for the seasons to change, they didn’t feel the newly autumn-tinged air. And perhaps autumn might have come and gone unnoticed if the long sleeves suddenly appearing in shop windows hadn’t announced its arrival.

Standing in front of one of those windows now was a young girl, her reflection looking back at her from the glass – a bit short, a bit freckled. The mannequins peering at her from behind the glass were tall and pretty, and perhaps that was why the girl made off quickly. A flock of pigeons took flight above her with a surprised flapping of wings. The girl muttered an apology as she continued walking, and the pigeons, having already forgotten what had frightened them, returned to perch on a nearby bench. At the entrance to the bank, a line of people snaked its way to the ATM. A deaf-mute beggar stood beside them, hand extended, and they pretended to be blind. When the girl’s gaze momentarily met his, she once again mumbled an apology and hurried on, she didn’t want to be late for her shift. As she was about to cross the square, a loud honk made her stop in her tracks and a large bus hurtled angrily past her. A poster on the back wished her a happy New Year. The Rosh Hashana holiday was still a week away, but the streets were already filled with promises of big sales. Across the street, three girls her age were snapping pictures in front of the fountain, their laughter ricocheting off the paving stones. As she listened, she told herself over and over again, “I don’t mind walking alone, I don’t mind it at all.”

She crossed the square quickly. Inside shops, red-haired saleswomen said, It looks lovely on you, adding, If I were you, I’d take two, as they stole glances at the clock. Bladders bursting, they could barely wait for their break. A charming young man stood at the counter, ringing up sales on the cash register with fingers that had run through his boyfriend’s hair earlier that morning. Customers left the shops, their swinging bags twisting around each other, creating an urban rustling that was as much a harbinger of autumn as the rustle of leaves falling from treetops.

In the adjacent ice-cream parlour, the girl went behind the glass counter and began handing spoons of ice cream to those who wanted to taste, knowing that the summer vacation was about to end and no one had yet tasted her, the only girl in her class still a virgin, and next summer, when the fields yellowed, she would be wearing a soldier’s army green.

Now she handed an ice-cream cone to the little boy standing in front of her and tried hard to smile as she said for the thousandth time that week, “Here you are.” The next person in line asked to taste the fig sorbet. Nofar knew right away that he wouldn’t buy fig sorbet, he would only taste it, along with ten other flavours, and in the end he’d ask for chocolate. Nonetheless, she scooped a bit of fig sorbet onto a plastic spoon and glanced quickly at the clock above the counter. Only seven more hours to go.

At that very moment, the door opened and they stepped inside. She had been waiting the entire summer for this moment and had even written about it in great detail in her notebook: Yotam would come in and be surprised to see her there. She would offer him ice cream free of charge, and in return he would offer her a ride home on his motorcycle. She would say that she still had a few hours left on her shift, and he would say that a few hours wasn’t a long time to wait. But when the moment finally arrived, three days before the end of the summer vacation, Yotam didn’t come in alone. He was surrounded by his crew of friends. And one of them was Shir, who, until four months ago, had still been Nofar’s friend. Nofar’s only friend, to be precise.

The five of them stood there, and although they weren’t particularly good-looking as individuals, standing there at the counter they seemed to Nofar to be incredibly beautiful. They shone with the glow of being a clique, as if the fact that there were five of them made each of them appear at least five times more beautiful. They examined the row of flavours spread out before them, trying to decide, and for a moment Nofar dared to hope they wouldn’t recognize her. But finally Yotam raised his beautiful eyes from the ice cream to the counter, frowned slightly and said, “Hey, you go to school with us.” The others looked up. Nofar fought the urge to avert her eyes. “You’re in Shir’s class, right?” Moran asked as she pulled her hair back into a ponytail in a gesture that was as ordinary as it was charming. Nofar nodded quickly. Yes. She was in Shir’s class. In fact, she had sat next to Shir since the second grade, until that morning four months ago when she arrived at school to find that Shir had fired her without even a letter of warning.

There was a moment of silence before Yotam said, “So, I’ll take cookie dough.” Nofar had already begun piling ice cream into a cup when he said, “In a cone.” And that, in fact, was all Yotam said to her because immediately after that the others began telling her what flavours and toppings they wanted, and Moran added in a tone brimming with insincere amiability that they needed to get their ice cream in a hurry because the film they wanted to see started in twenty minutes. And all the while, Shir stood silently looking at Nofar, a small expression of guilt on her face, until she finally said she’d have vanilla. She didn’t have to say it, Nofar knew what flavour Shir liked. Five minutes later they were already outside, on their way to the film. Nofar looked at the sorbets displayed under the counter in flowering layers of red and orange. Dozens of fingerprints covered the glass partition in front of her, all made by fingers pointing at the ice cream, never at her.

The glass door opened and a gang of noisy children burst inside. When this day was over, she’d play music she liked, not the songs that Gaby insisted attracted customers. She’d still have to pick up all the napkins people had dropped and the sticky spoons parents hadn’t felt like throwing away after their kids finished their ice cream. She’d still have to wash the floor, scrub the fingerprints off the partition and take out the waste bins, but it would be her music in the background. Then she’d fill a styrofoam box with ice cream and take it to the homeless guy who stood near the fountain. Or maybe she’d just put it down not far from him, because the last time she went up to him he had shouted some garbled words at her that she didn’t completely understand.

She’d been dreaming too long about the homeless guy and the ice cream, and about the gang at the cinema without her, because when she looked around she saw that the kids had taken off with their ice cream without paying. Gaby would deduct it from her salary. A large lump of misery filled her throat and she took a deep breath and swallowed it whole. Six and a half hours to go. If only this day would end already.

She didn’t know that this day would end differently from all the days she had known before, that this day would change all the days that followed, that this was absolutely the last day she would be nothing more than a drab ice-cream server.

She weighed 3.4 kilograms at birth. Beyond that, there was nothing to say about her, simply because a moment before that she hadn’t existed. The people who, a moment earlier, had been called Ronit and Ami and were now called Mom and Dad, looked at her through a haze of emotion. The birth had taken nineteen hours, and at its conclusion Ronit’s vocal chords were almost as frayed as Ami’s eardrums. The newborn baby girl lying between them was very red and very wrinkled, but the delivery nurse told them it was only temporary, “She’ll be beautiful!” she said, “like a flower!” It wasn’t clear what the source of the nurse’s prophetic confidence was, but the parents accepted her words as fact. Ronit picked up the baby gently, astonished at those 3.4 kilograms that only a short time earlier had been part of her own body weight and now existed on their own. “We’ll call her Nofar,” Ronit said in a hoarse voice, “and she’ll be beautiful!” Ami was quick to nod, “A flower!” The nurse went off to other rooms and other deliveries. And so, before she was ten minutes old, the baby girl had a prophecy and a name that meant “water lily”.

Choosing a baby’s name is no small matter. The first tiny cells are only just beginning to divide in the womb and the parents are already divided in their opinions: one wants Tamir and the other demands Daniel, one insists on Michal and the other decrees Yael. It would be better to wait for the cells to mature into an actual creature so that the name is born from the person instead of the person being born into the name. But parents, unable to control themselves, are driven by their hopes and expectations to plunge ahead, and hopes and expectations have a way of outdistancing reality, creating so large a gap that the child is left behind, forever running to catch up to her parents’ dreams for her. Nofar wasn’t ugly. Far from it. But the delivery nurse had said, “Beautiful!” and that prophecy had pursued her from infancy. She grew up to be a timid, withdrawn young girl who lived in the world as if she were an uninvited guest at a party. Now, standing behind the counter in the ice-cream parlour, she recalled that moment when Yotam and his friends had come in and he had recognized her. “Hey, you go to school with us.” It was clear to her that he hadn’t known her name. And that he hadn’t cared enough to ask.

When the stream of customers in the ice-cream parlour slowed to a trickle, Nofar took the key that was hanging on a hook like a suicide and hurried outside to the employees’ toilet in the alley. A pair of alley cats stopped copulating for a moment to glance angrily at her, and then, with a wave of their tails, went back to their business. Nofar squeezed into the narrow cubicle and closed the door quickly, as if it weren’t two cats she had just seen copulating, but, heaven forbid, her parents.

When she left the cubicle she straightened her blue dress with a trembling hand. She had borrowed it from her sister at the beginning of the summer. How hopeful she had been then that it wasn’t only the dress she was borrowing, but also the charm required to carry off wearing it. Her younger sister moved with such grace, such fluidity that the city’s traffic lights blushed with pleasure whenever she approached. The already traffic-congested streets grew even more congested because the lights became flooded with such a red wave of lust that traffic was forced to a standstill. And so Maya strolled from one pedestrian green light to another without ever having to wait, not even at the busiest intersections. But for Nofar it was different. She always waited.

When they were infants, people couldn’t tell them apart. Nofar was less than a year older than her sister, and Maya closed the gap with the speed of a gazelle. She was born prematurely, and though the doctors attributed that to Ronit’s emotional state (her husband was called to active reserve duty when she was in the last stages of pregnancy), the birth was actually premature because the baby inside was so eager to be equal to the one outside. The timid ice-cream server was not the least bit timid then. On the contrary. Plump and smooth as butter custard, reaching out with tiny hands to clutch any finger extended to her, the world was hers to grasp and taste. The word “daddy” was sweetening under her tongue, ripening slowly, a first gift to her parents to be given at the right moment. But when that moment came, her father was gone and her mother, who at first had been as bright as a summer dawn, now flitted around the house like an agitated bird. Nofar knew the story well, family members told it regularly, and just as she learnt at school to stand to attention when the anthem was played, she followed the rules of the ritual whenever she heard that family anthem, listening with her head bowed at the sound of the familiar words and mumbling, “Thank God” at the appropriate times. ThankGod, that when the ambulance took Mom, the neighbour called Dad immediately. Thank God, Dad managed to get to the phone a minute before the ground operation began. Thank God, that when the commander heard about Dad’s new baby girl he gave him a twelve-hour pass, and – here saying “Thank God” was not allowed, she’d fallen into that trap once and her mother had shot her a withering glance – who would have believed it, right after Dad left, his tank crossed into Lebanon and everyone was killed, thank God Maya’s birth saved Dad. As the years passed, the last sentence became slightly shortened to simply: thank God, Maya saved Dad. Not Maya’s birth, the medical event. Not the commander, who had given him a pass. Maya had saved Dad. Everyone knew it and everyone talked about it, and when Nofar finally said the word “daddy” they barely noticed. Because that’s just how it is, all babies eventually say “daddy”, but not all babies rescue their fathers from a burning tank.

On her first day of work at the ice-cream parlour, Nofar left her house wearing Maya’s dress, in better spirits than usual. For the first time in her life she had a chance to begin everything anew, and there was no better place for it than the ice-cream parlour, that wonderland of flavours and colours, as if someone had managed to trap a rainbow, attach a door at the front and a cash register at the back and place it on a street corner. Her parents had praised her for deciding to work during the summer vacation, but she hadn’t done it only for the money. It was for the people that she went there, a fifty-minute ride from her house in the suburbs. It was for the welcome eyes of strangers who didn’t know what the neighbourhood knew about her: that there was nothing to know about her. That nothing had ever happened to her. No adventures. No misadventures. A marginal, harmless existence that was now seventeen years old.

Even the pimples on her face weren’t enough to make her unique. There are teenagers who have truly exciting geological formations on their face: deep craters, unforgettable hills and valleys. Nofar’s sebaceous glands, however, behaved moderately, satisfied to appropriate only her forehead and a small enclave on her nose. But the pimples, though they bothered no one else, bothered Nofar herself quite a bit. In her mind, she called herself “zit face”.

Names and nicknames are very dangerous things. Lavi Maimon, who lived on the fourth floor of the building that housed the ice-cream parlour, could tell you that. Despite all the scoops of chocolate that had rolled around in his stomach, he was still as skinny as the bars of the bicycle racks the city installs on the streets. Perhaps he could have borne the humiliation of his existence if his parents had given him a name that was easier to live up to than Lavi, which means lion, but he carried the burden of the king of the jungle himself on his skinny shoulders. As a child, Lavi had waited for the mane to grow in and the muscles to develop under his skin when he finally reached his teens. But the years passed and the hair refused to grow – he had only fourteen hairs on his chin, he counted them in front of the mirror every night – and as for the muscles, well, forget it. His father, Lieutenant-Colonel in the reserves Arieh Maimon, ran his business with the same iron fist he had once used to command his soldiers. And just as Arieh Maimon’s soldiers had kept climbing the hill because they were less afraid of the terrorists shooting at them from above than they were of their hot-tempered commander below, so the stock of the company Arieh Maimon had founded after his discharge also continued to climb well beyond every economic forecast because it feared the fiery glance of its commander.

Lieutenant-Colonel Arieh Maimon did not give his son the name Lavi. That decision was made by his wife, a beautiful young woman who admired her husband, the country and her Pilates teacher, not necessarily in that order. Since she was especially fond of the name, her husband generously allowed her to make the choice. As the boy grew into a teenager, it was clear that he did not possess even a smidgen of his father’s predatory charm. If there was any connection between him and the world of large felines, it was only as a potential meal. In his son’s early years, the father still roared at him and pierced him with the same look that had once driven his soldiers and then his stock upward. But after a while he stopped doing even that. Lavi began to miss the loud reprimands, even the roars. Anything was better than the silence, the quiet that followed the disappointment.

In the evening, as his mother made her ablutions in preparation for her Pilates class and his father purred contentedly in front of the TV, Lavi opened the window in his room and looked down at the street. The urban river rushed by below him, gangs of teenagers on vacation bobbing and lurching in the current. Hearing their laughter, he asked himself whether they would keep laughing if his body landed beside them, a dull thud on the paving stones. Whether the girls would bend to help, run slim fingers over his short-cropped hair, the disappointing mane. Whether they would finally look at him – if not with compassion, then at least with interest – take out their mobile phones and snap a picture of the sprawled body, its arms embracing the street, arms that had never embraced a girl.

And so, every evening the city adorned itself with the glitter of street lights and Lavi Maimon stood at the window contemplating his death, thinking about the many faces that would look at him when he landed near the entrance to the ice-cream parlour. He would have tried his hand at that sort of flight a long time ago if the summer military operation on the southern border hadn’t begun, flooding the city with sirens and filling all the newspapers. To be buried somewhere on the back pages was not what he wanted. He preferred to wait for the fighting to end. And thank God, it never did: it stopped in the south only to begin again in the north. Lavi woke up every morning and saw that the newspaper was filled with the same stories that had filled its predecessor the day before. How would they find room for the story of his failed attempt to fly? So he postponed his death from day to day, and though the military operation cost many lives, it did at least save the life of one city boy.

As Lavi groaned under the name of the lion crouching on his shoulders, Nofar Shalev also buckled under the burden of her name. Why in the world had she believed that here, in the ice-cream parlour of all places, she would finally blossom into a different Nofar? Every morning she stood behind the counter. Summer came to the city, had its merry, sweaty way with it, and now that autumn was approaching, everything had a façade of respectability once again. In another few days, Nofar would go back to school without a single exciting story from the ice-cream parlour in the city except for the ones she wrote in her notebook. How much she had hoped for a brazen love affair with a student, or a tourist, or a heavily pierced bad boy. When she returned to school he would wait outside the gates for her, she would run to him and everyone would see. Including Shir. And Yotam. Nofar had been prepared for anything but returning to her senior year with empty hands, with fingers that had never touched a boy’s except to give him change. If she had at least found a girlfriend here to replace Shir. Anything to be the entire focus, even for a moment, of someone’s gaze.

On the fourth floor, Lavi Maimon stood looking down at the street. In the alley stood Nofar Shalev, her hands straightening her dress, neither one aware of the fact that they were not alone in suffering the humiliation of a name they could never live up to. It might have been easier if they had known that somewhere – on the other side of the planet, or four floors away – someone was enduring the same pain. Or it might not have been easier at all, just as someone with toothache feels no relief at hearing the moans of the person sitting next to him in the dentist’s waiting room.

Although Lavi Maimon and Nofar Shalev knew nothing about each other, they both sighed forlornly at precisely the same moment. The only difference between them was that Lavi continued to stand at the window while Nofar, suddenly realizing that she was late getting back from her break, began running. She ran quickly, almost as if she knew that it wasn’t only to the ice-cream parlour that she was hurrying now, but to the moment when everything would change, to the fate that already awaited her on the other side of the counter.

2

OVER THE LONG DAYS she spent behind the counter, Nofar had developed a habit – she looked into the customers’ faces and tried to guess which of them had come into the ice-cream parlour by accident and which were there by design. The accidental visitors were nicer: people strolling leisurely down the street, sailing along like fish until the ice-cream parlour’s welcoming sign appeared and reeled them in on its line. The ones who planned to be there were totally different, people for whom the ice-cream parlour served an actual purpose: compensation for a hard day’s work, the object of desire of a crushed heart. She saw it in their darting eyes, in their tight mouths that insisted on tasting more and more flavours, all of them unsatisfying. That kind of customer gulped down his ice-cream cone as if it were a headache pill: quickly, so it would have an immediate effect.

Nofar could easily see that the customer waiting at the counter now belonged to the intentional group. It wasn’t a leisurely stroll that had led him there, but rather a disastrous day. She said good evening and wasn’t surprised when he didn’t reply. She asked what she could get for him, trying hard to smile even though she was exhausted from her dash across the alley and the barrenness of the summer. The guy looked her over impatiently and grumbled that he’d been standing there for ten minutes already. How long did a person have to wait for service in this place?!

That wasn’t accurate. He hadn’t been standing there for ten minutes. In fact, he’d been standing there for less than five. But during those five minutes, he’d received a text from his agent saying that the TV bigwigs had thought it over and decided they didn’t need another talent show. What his agent didn’t say was that even if the bigwigs had been convinced they did need such a show, they still didn’t need the services of a singer whose glory days were behind him. Seven years behind him, to be precise. It was unbelievable how quickly seven years could pass. Only a minute ago he’d been riding high, his picture on the front pages of newspapers, one and a half million texts sent to him on that amazing night, an entire country sending him its love in digital letters. Now he was here, in this pathetic ice-cream parlour standing in front of this pathetic girl who looked at him, expecting to hear what flavour he wanted, and there wasn’t the slightest hint of recognition on her face. She didn’t know who he was.

Later, when the echoes of the scandal died down a bit, Avishai Milner would wonder whether it had all started at that moment. A girl looking at him with blank eyes from the other side of the counter, and in that blankness he lost his soul. There he was, sinking, drowning in the darkness of anonymity, in the abyss of ordinariness. Across the counter from the girl, Avishai Milner couldn’t breathe. With his last ounce of strength, he fought to remind himself that he wasn’t just another customer, he was Avi-shai! Mil-ner! That was how the presenter on the finale had introduced him, slicing his name as if it were hot, fresh bread, lengthening the syllables to the pleasure of the studio audience, Avi-shai! Mil-ner! And the viewers at home had applauded with one million votes. For the next several weeks his name was on everyone’s lips, beautiful women swooped down on him in pubs and clubs, wanting to taste him, wanting to be tasted by him, and he made love to them, but even more to himself. He screwed Avishai Milner’s brains out, and every nymph who sighed A-vi-shai in his ear was merely echoing that unforgettable moment when his name had been announced, when the presenter had opened the envelope, looked at the name with his kind, generous eyes, and in front of the huge audience in the studio and at home, crowned the small-town young man: Avi-shai! Mil-ner!

There’s no way of knowing what went wrong after that. Avishai Milner was neither a better nor a worse singer than Eliran Vaknin, who had been crowned by the same presenter the previous year and appeared on all the hit-parade lists to this day. Nor was he less good-looking than Assi Sarig, who was crowned the following year and had already played a tormented doctor in a TV series, a tormented soldier in another TV series, and the tormented father of an autistic child in a soon-to-be-released feature film. The fact that there was no reason for it, no personality defect that could be blamed, no lesson to be learnt – that was what tortured Avishai Milner more than anything. The total arbitrariness of his fall terrified him because it implied that his rise had also been arbitrary, not the product of his talent, but of a random set of circumstances.

Avishai Milner received his agent’s text after long weeks of anticipation. Since submitting his proposal to the TV bigwigs, his days had been suffocating and his sleep sporadic. Like a wild bull, Fame had tossed him over its shoulder and then kicked him as he lay on the ground. He had to find a way to rise again. The longer the bigwigs took to give their answer, the more nerve-racking it was. The presenter came to him in his dreams and held his hand, saying that after the commercial they would sing a duet together, but to his horror he couldn’t remember the words and the microphone turned into a terrifying snake in his hand. In short, he really did deserve ice cream. But when he went into the ice-cream parlour he found it empty. Outside, customers were sitting and eating happily, but behind the counter there was no one.

Someone who receives bad news in the middle of an ice-cream parlour – what does he need? A steady hand offering him a variety of chocolate comforts. A smiling face waiting patiently for him to speak. Eyes that look into his and confirm that yes, despite everything, he still exists. But when Nofar returned to the counter she didn’t recognize Avishai Milner, and although she did her best to smile, her smile couldn’t hide the sadness that emerged from beneath it, the way a too-small shirt she had once tried on couldn’t cover her embarrassed flesh. Avishai Milner didn’t know that the dress the girl was wearing belonged to her more beautiful sister. He didn’t know that she had made her way there every day that summer in the disappointed hope she would be rescued from ordinariness. All he knew was that he’d already been waiting ten minutes to be served here. And that was inacceptable.

“This is inacceptable,” Avishai Milner said to the girl standing opposite him, and to emphasize exactly how inacceptable it was he slammed his hand on the glass partition.

“Unacceptable,” the girl said.

“Excuse me?!”

“The word is ‘unacceptable’, not ‘inacceptable’.”

As the oldest daughter of a language teacher, Nofar knew very well that people hated nothing more than having their words corrected. No one would open a friend’s mouth while he was eating, pull out the food and demonstrate the right way to eat. And words, like food, belong to the tongue on which they rest. But then this customer came into the ice-cream parlour and stood across the counter from Nofar. A nasty guy who banged on the glass partition, leaving another greasy hand print. But not to point out a flavour. The hand that slammed on the glass wasn’t pointing to the mango sorbet or French vanilla. The guy wasn’t making a choice, he was asserting control: he banged on the glass partition simply because he could.

Nofar was seventeen years and two months old on that evening, and in all her days on earth it had never occurred to her to bang on a counter. That’s how it is, there are people who bang on counters and there are people who wait behind counters and ask, “What’ll you have?” But something burst inside her that evening. Yotam and Shir’s crew on the way to the cinema. Her sister’s dress. The humiliation of that depressing summer. She didn’t need this guy’s complaints. But if he insisted on complaining, then he should use the proper language. Otherwise it was unacceptable.

Avishai Milner looked in astonishment at the server who had corrected him. He’d never seen such chutzpah before. He had always considered himself a man of words. He’d written the lyrics to his songs himself. Now he mobilized all his skill to ram his words into the girl’s flesh. “You pie-faced moron! You stupid cow! You should tweeze your eyebrows before going out in public. And those pimples, didn’t anyone ever tell you not to squeeze them? You just need a few olives on your face and they can sell it as a pizza. But forget the face, what’s with that stomach of yours? Didn’t the owner of this place tell you that if you eat too much, you’ll look like a hippo? Who would ever want to fuck you, huh? I’ll take one scoop of cookie dough.” He handed her a 200-shekel note and Nofar, standing on the other side of the counter, automatically reached out to take it, like a chicken without a head that keeps running around for a few seconds. Her limbs repeated routine actions, taking a cone and scooping the ice cream into it, until the realization hit her that she had been decapitated, that the man had removed her head, her selfhood, and she threw down the cone and fled.

3

THE PAIR OF ALLEY CATS screeched a few mating calls and were about to renew their copulation, which had recently been interrupted. But at that moment the ice-cream server burst into the alley and dashed past them, heading for the toilet. Eyes blazing with anger, the long-tailed creatures observed the flight of the sobbing invader, but she was too agitated to notice them. The customer’s words still thundered in her ears. Tears rose in her throat. Her nose. Her eyes. To think that he had really said those things to her, that she had really stood there listening mutely and had almost served him ice cream. How pathetic she was. There was only one thing she wanted now: to disappear. The most terrible things she said to herself had just been said to her by a stranger: she was ugly. Hairy. Pimply. Fat. That no one would ever want her. And though she was, in fact, quite nice-looking, the rejected little girl inside her was still certain that the customer at the counter had said aloud what everyone thought: the customers at the table, her classmates, her father, her mother, her sister. With her last ounce of strength she sought a place to hide, and the only one she could think of was the foul-smelling cubicle she had stepped out of a short time earlier. She was about to enter that tiled womb and squeeze between the waste bin and the raised toilet seat when, suddenly, a strong hand grasped her.

In the weeks to come, Avishai Milner would be asked again and again what had made him follow that underage girl from the ice-cream parlour to the toilet. He, for his part, would continue to insist that he wanted to demand change for the 200-shekel note he gave her and believed she had taken with her when she left. The simple facts would not help Avishai Milner: the money was not taken by the girl, but left on the counter. Though he would steadfastly claim that he did not see the note when he went out after her, that claim, like most of the facts in the incident, would be eclipsed by the enormous impact made by the scream the girl emitted when Avishai Milner grabbed her.

The cashier in the dress shop raised his head. The red-haired saleswoman stopped in the middle of folding a blouse. In the neglected alley, the pair of alley cats scurried off. And Lavi Maimon, sitting on his fourth-floor windowsill, realized that he would have to postpone his jump once again. Nofar Shalev looked at Avishai Milner, who had insulted her and was now clutching her hand, and screamed her heart out.

Some changes occur slowly. Geological erosion, for example, sometimes continues for tens of thousands of years. Water and wind do their job and gradually, bit by bit, a mountain ridge becomes a valley, a sea turns into a desert. Time, like a giant anaconda, crawls along lazily, swallowing up the tallest mountains. And some changes erupt all at once, like a match bursting into flame, and the “let there be light” of creation. The change that happened to Nofar was apparently of the second kind. She had walked the earth for seventeen years and two months and had never thought to pound on counters, much less to scream in alleys. But now, in the presence of that man who said those horrendous things to her, Nofar’s very soul shuddered. She ran out to the alley determined to disappear, but when that customer grabbed her hand she was suddenly overwhelmed by the opposite urge – to be heard. She screamed out the humiliation of the words he had hurled at her. She screamed out the humiliation of the words she had hurled at herself. She screamed out the disappointment of that summer and the summers before it. She screamed and screamed and screamed, and didn’t hear the police sirens arriving in response, or the fire engines that joined them, because so it goes, one jackal howls and one hundred jackals respond from the darkness. Nofar Shalev screamed and the city responded with screams of its own.

The entire street hurried to see what was happening there, in that neglected alley, and since Nofar Shalev was the one it was happening to, everyone looked at her. The dreamy-eyed cashier. The red-haired saleswoman. Neighbours from their balconies. Two traffic cops. Even heavily pierced members of street gangs, the sort that never show an interest in other people and are never the object of other people’s interest, came to see what was happening. Nofar’s body was awash with the kind of light that radiates from fondly gazing eyes, and that light was now focused – wonder of wonders – on a girl who had never before attracted a lingering gaze. A pretty girl soldier, her blonde hair pulled back in a ponytail that burst from the rubber band like a fountain of light, held Nofar in a kind embrace and said, “Everything’s fine” with such certainty that it seemed she had the authority to say those words, not only in her own name but in the name of the entire defence establishment. Nofar gave herself over to the warm embrace, feeling as if she had never been hugged that way before. The light fragrance of the perfume worn by the fairy godmother in uniform enveloped her along with another more masculine scent, that of the officer who only a moment earlier on the street had encircled the girl soldier’s waist with his arm before hurrying with her to the alley after they heard the scream. As she held Nofar in her arms to comfort her, the officer and two traffic cops held Avishai Milner and demanded to know what he had done to the girl to frighten her so badly.

Nothing, he shouted, I didn’t do anything, and the poor girl trembled in the kind embrace because she knew it was true, he hadn’t done anything to her, that dirty-mouthed customer hadn’t done anything to justify the presence of two traffic cops and an army captain. A citizen of the country was certainly permitted to skewer the heart of another citizen with his words. In another moment, she’d have to say that to the gentle-eyed girl soldier, to the audience looking at her with the sort of affection she had never before experienced. Everyone was so friendly, so interested – what would they say when they discovered that nothing had actually happened, that they had run all the way there for no reason? They would turn their backs on her instantly. The policemen would certainly rebuke her for causing such a fuss, and she would bow her head in submission, as she always did. Then she would return to the ice-cream parlour to serve the waiting customers, wipe the glass surface, ask, “Cup or cone?” and “What can I get for you?”

And in truth, she would have been willing to accept all that if Avishai Milner hadn’t opened his filthy mouth again. It seemed that he hadn’t vented all his fury. Or perhaps it had been recharged, like those almost dead phones that are suddenly revived by a newly found source of power. So it was with Avishai Milner, peoples’ glances replenished him. How much he had missed that audience, young and old, soldiers and policemen – as the presenter used to say, the entire country is here with us. Suddenly he was filled once again with the familiar, addictive feeling of being at the centre of things, the object of frenzied public attention exploding all around him. But the fact that the attention was negative – no one threw flowers to him, no one applauded him – shook him to the depths of his soul. The audience’s affection was lawfully his. He couldn’t let that hippo who had kept him waiting at the counter, who had dared to correct his language and had run off with his money, steal what was rightfully his.

Once again, he snarled his nasty words at the girl, and words, like hot-air balloons, take off when the flame under them is lit: “You disgusting hippopotamus, I wouldn’t touch you with a ten-foot pole,” and a host of other pejorative words and phrases. The girl’s eyes filled with tears – first he had insulted her when no one else was around, and now he was ridiculing her in front of everyone. In despair, she moved out of the pretty girl soldier’s embrace, began to cry in earnest and covered her face with her hands. Beyond her hands rose a monumental brouhaha, everyone was asking questions at once, but, deafened by her own sobs, Nofar didn’t hear, and it wasn’t her fault that observers took her sobbing as confirmation. They asked, “Did he touch you?” and the covered face trembled, that is, replied in the affirmative, and each additional sob was further confirmation, each additional sob was the next day’s headline. Suddenly, miraculously, the following story emerged from a neglected alley – refugee from reality TV accused of attempted rape of minor – and everyone looked at the newborn story and saw it was good.

Alley cats stand up a few days after emerging from the womb. Foals manage to stand up about an hour after birth. Only human babies, slow creatures that they are, cannot stand on their own two feet until many months after they are born. In contrast to the slowness of the human newborn is the incredible speed of the human story: a person brings a story into the world, and if it contains a whiff of scandal, it immediately stands on its feet. One minute it clings to its creator, and the next it breaks into a run. The question is not where it has come from, but where it is going and how far it will go before surrendering to the law of nature that halts all runners.

The terrible story about the famous singer and the underage ice-cream server came into the world at 6:49 in the evening in the month of August. For a brief moment, the newborn story remained where it was and breathed the perfumed evening air, but then it was no longer willing to wait even one minute longer in the alley. It galloped far into the distance, and the alley, which had filled so quickly earlier, now emptied out with the same speed. The traffic cops and the firemen, the golden-haired girl soldier and her lover, the officer, and of course the proud parents, the famous singer and the minor from the ice-cream parlour all went on their way. It was now impossible to know whether they were leading the story or the story was leading them, but either way, the alley was already too small for them. For their present size they needed a larger living space, such as, for example, the police station on the main street.

4

IN THE POLICE STATION on the main street they gave her water and tea, then Coke as well. They cut her a slice of the honey cake one of the dispatchers had brought. They offered her a seat, and when her bottom touched the chair Nofar sighed in relief. She had been standing on her feet without a break all summer. She stood when she served the customers who flowed into the ice-cream parlour, and when they left she hurried to clean the glass counter, but the moment it was shiny again the customers were back, and the cycle began over again. Now, with her legs stretched out in front of her, a glass of cold Coke in her hand, its bubbles fizzing merrily, she was asked once again what had happened. The pleasant woman across from her leant forward. She had beautiful, delicate hands with nails polished a lovely, subdued colour so light it was almost transparent. The pleasant woman said her name was Dorit and that Nofar was probably finding it difficult to speak and answer questions. But in fact, it wasn’t difficult at all. It was harder when nobody asked you anything, when you spent an entire day, an entire week, an entire summer without speaking to anyone. The woman asked, Nofar replied, and it was all incredibly simple. All she had to do was repeat what had already been said, just like in a history exam. She was very good at memorizing. There was a reason she was an outstanding student. The words flowed effortlessly. The woman across from her had all the time in the world. Her kind eyes were fixed exclusively on her, no distractions, and, faced with such attentiveness, Nofar found herself opening up. The delivery nurse’s old prophecy was coming true: her body forgot its awkwardness. Her cheeks reddened. Fire ignited in her eyes. Her usually pale, stammering lips grew suddenly as red as a rose. A stranger happening into the room and asked to describe her by the way she spoke would undoubtedly say: blossoming.

That was her mother’s word: blossoming. When Nofar completed primary school, her mother promised she would blossom in middle school, and when she completed seventh grade her mother said that the transition to middle school was always difficult, but now, in the eighth grade, she would really, really blossom. And so she moved from class to class, dragging behind her a trail of buds that would open any minute now. How strange it was to discover that the change that had been so late in coming when she entered middle school, even when she began high school, occurred one autumn evening in a small room in a police station – the more she spoke, the more she blossomed.

Finally she stopped, though she could have kept going if she had wanted to. Dorit, the detective with the pleasant face and delicate hands said, “You’re a very brave girl.”

In a side room on the police station’s second floor, Avishai Milner banged on the wooden table. “I’m telling you I didn’t touch her!” The two detectives sitting across from him were not especially impressed by the banging, and even less impressed was the wooden desk. It had already been pounded so much in its life, sometimes by suspects, sometimes by detectives, that it had long since lost hope of being rescued. Its production-line brothers had been placed in public libraries and post offices, one of them had even risen to the census bureau office, but fate had doomed this