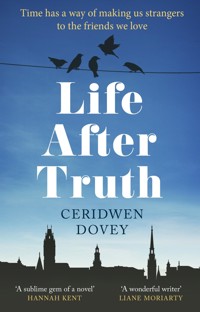

8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'A sublime gem of a novel' Hannah Kent, author of Burial Rites Fifteen years after graduating from Harvard, five close friends on the cusp of middle age are still pursuing an elusive happiness and wondering if they've wasted their youthful opportunities. Mariam and Rowan, who married young, are struggling with the demands of family life and starting to regret prioritising meaning over wealth in their careers. Jules, already a famous actor when she arrived on campus, is changing in mysterious ways but won't share what is haunting her. Eloise, now a professor who studies the psychology of happiness, is troubled by her younger wife's radical politics. And Jomo, founder of a luxury jewellery company, has been carrying an engagement ring around for months, unsure whether his girlfriend is the one. The soul searching begins in earnest at their much-anticipated college reunion weekend on the Harvard campus, when the most infamous member of their class, Frederick – senior advisor and son of the recently elected and loathed US President – turns up dead. Old friends often think they know everything about one another, but time has a way of making us strangers to those we love – and to ourselves...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ALSO BY CERIDWEN DOVEY

Blood Kin

Only the Animals

In the Garden of the Fugitives

Writers on Writers: On J.M. Coetzee

Inner Worlds Outer Spaces: The working lives of others

SWIFT PRESS

First published by Audible 2019

First published in Australia by Penguin Random House 2020

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2021

Copyright © Ceridwen Dovey 2019

The right of Ceridwen Dovey to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-80075-013-5

eISBN: 978-1-80075-014-2

This is a work of fiction.

While certain events and longstanding institutions are mentioned, the novel’s story and characters are the product of the author’s imagination.

. . . the Love-god, golden-haired, stretches his charmed bow with twin arrows, and one is aimed at happiness, the other at life’s confusion.

— Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis

Harvard Class of 2003 – Fifteenth Anniversary Report

JOMO GÜNTER-RIEHL. Address: 200 Church Street, Apartment 7A, Tribeca, New York, New York 10013. Occupation: Founder & Director of Gem Acquisitions, House of Riehl Luxury Jewelers. Graduate Degrees: MBA, University of California, Berkeley ’13.

Last time I wrote one of these updates it was to brag about my life. I’d just finished my MBA and launched a lucrative jewelry start-up, creating bespoke pieces showcasing gemstones with weird names like jeremejevite and wulfenite. I was flying around the world on private jets, partying hard, barely sleeping.

Then my business partner bailed on me, my company almost went under, and my mom was diagnosed with cancer. The going got tough for a while.

Five years later, I’m through the worst. I’m back to living the good life but not the high life. My mom’s cancer is in remission. My company is doing great but not so great that I lose perspective or get too comfortable with success. I finally made the trip back to Dad’s homeland, Tanzania, where I swam in the clear seas off the island of Zanzibar and camped with my best friend at the rim of the Ngorongoro Crater.

The learning curve has been steep, and I’m not immune to falling back into bad habits – one of which is that I don’t always make as much time as I should for the people I care about. So I’m eager to catch up at the reunion with my blockmates and also my Spee Club brothers and, now, sisters. We were the first final club to admit African-Americans, and I couldn’t be more proud that we are now also the first to welcome women members.

JULIET HARTLEY. Address: c/o Jackson Greene Entertainment Associates, 4400 Wilshire Boulevard, Beverly Hills, California 90211.

ELOISE ABIGAIL McPHEE. Address: Kirkland House, 95 Dunster Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138. Occupation: Academic. Graduate Degrees: PhD, Harvard, ’08. Spouse/Partner: Binx Lazardi (AB, Harvard ’13), December 31, 2015.

It feels like just yesterday I was proposing to my wife, Binx, on the dance floor at our tenth reunion. On that mild spring evening, we were honored to have so many of you witness – and celebrate – our decision to commit ourselves to each other for life. (Thanks, also, to the kind soul who anonymously sent a magnum of champagne to our hotel room later that same night.)

In my professional life, after grueling years sprinting around the tenure track, I’ve been appointed as Professor of Hedonics, which is the science of happiness and pleasure, if you’re wondering. The epiphany that led me to where I am now took place in the basement laundry of Weld Hall in my freshman year. I was filled with a positive emotion I realized I had no proper vocabulary for – something to do with the smell of the fabric softener and the sense that my future was wide open. At every freshman orientation event, we had been educated in how to recognize the first symptoms of depression, and all the varieties of misery and anxiety we might expect to feel in the coming year as students. Nobody had prepared me for those early symptoms of great joy at being young, bright, and bursting with hope. Nothing had been said about the human capacity for happiness. Then I’d paged through the course catalog during Shopping Week and discovered – cue angels singing and sunlight piercing the gloom – an obscure class on positive psychology. And the rest, as they say, is history.

People generally ask me, when they learn what I study, if I can share with them the secret to being happy. I usually respond by quoting my wise colleague Daniel Gilbert: ‘Happiness is a noun, so we think it’s something we can own. But happiness is a place to visit, not a place to live.’ The thing to remember is that very little of anybody’s day is spent feeling happy. It’s an emotion designed to be fleeting. And you cannot pursue it directly, which is why the things that we think will make us happier – a promotion, a windfall, a new car – have little lasting effect. This is called the hedonic treadmill, which is like a personal-happiness metabolism. Even after a big change in our lives, whether positive or negative, in time most of us return to the same baseline.

Binx and I waited until all our compatriots could legally marry nationwide before we officially tied the knot, and we’re now fortunate enough to be residing on campus again . . . as House Masters (Mistresses!) of Kirkland House, though the official title is now Faculty Dean. I miss the top-floor garret I lived in my senior year, though I don’t miss the weak water pressure of those ancient showers (Jules and Mariam, you know what I’m talking about). Our current quarters are rather roomy, and, Kirkland alums, you’ll be glad to know that every Sunday evening at the Open House we still make sure to serve the giant wheels of baked brie that are responsible for many a sophomore fifteen . . . but in my opinion are worth every extra pound of flesh around my middle.

We will be hosting drinks at our place from five to seven pm on Thursday evening of the reunion long weekend, all classmates and partners welcome (though no young children, please). Donations at the door will go to the non-profit organization Binx recently founded, Who-Min-Beans, which advocates for posthumanists suffering discrimination for their beliefs.

MARIAM WEBSTER. Address: 1609 Bushwick Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11207. Occupation: Mom, pastry chef, and educator. Spouse/Partner: Rowan Anthony Webster (AB, Harvard ’03), May 25, 2003. Children: Alexis, 2013; Eva, 2017.

Greetings, friends!

Rowan and I are still renting in Bushwick. From our decrepit brownstone we look out onto the Evergreens Cemetery. We almost named our second daughter Bojangles in honor of Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson, the legendary tap dancer who is buried there and near whose grave we picnicked frequently while I was pregnant with her. Luckily childbirth brought me back to my senses, and we called her Eva.

We love the area, though we’re conscious we are part of the first wave (second wave maybe?) of gentrification that is destroying the community around us. We placate our consciences by being active supporters of the Do-Not-Go-Gentry network. I contribute muffins to meetings; Rowan contributes much more useful community-organizing skills. In September, our older daughter will start kindergarten at the local public elementary school where Rowan is the impassioned and tireless principal.

On the one day a week I’m not home with our girls, I put my chef-school skills to work as an educator at the nearby Rising Dough Collective, teaching at-risk teens how to bake really amazing bread so that they can get jobs at up-market bakeries beloved by gentrifiers everywhere. There’s an irony in this I’m not yet sure I want to unpack.

Since my father passed away two years ago, and with everything that Syria has suffered in recent times, I have felt a resurgent interest in exploring my family’s Syrian Christian roots. This past winter, I took Rowan and the kids along on a memorable visit to the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch in Paramus, New Jersey. I also recently learned that my name is the Syrian Christian version of Mary, mother of Jesus, or something like that, though I assure you nothing about our children’s conceptions was immaculate.

To stay sane, Rowan and I like to invent haikus to record our experiences of full-contact, 24/7 parenting, which many of you are no doubt also reeling from. I will share our most recent – scatological, of course – composition:

‘I’m ready to wipe!’

The summons most dreaded by

parents everywhere.

ROWAN ANTHONY WEBSTER. Address: 1609 Bushwick Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11207. Occupation: School Principal. Spouse/Partner: Mariam Webster (AB, Harvard ’03), May 25, 2003. Children: Alexis, 2013; Eva, 2017.

I should start by saying I have no idea what Mariam – my soul mate and fellow Class of 2003er – has submitted to this class report.

Next confession: I discovered my first cluster of gray hairs today. The horror, the horror! They decided to sprout all at once, clinging to each other as if they’re afraid of being alone. I’ll probably regret writing that, just as I now semi-regret sharing, in my tenth-anniversary report entry, the gory, wondrous account of the birth of our first child, Alexis. I will spare you the details of the birth of our second daughter, Eva, though let me be a proud birth partner and tell you that Mariam got through this birth, too, without any drugs except the concoction her own brain was making. I’m not supposed to weigh in on these things, and I know all births are beautiful however they happen, so I mention it here only because seeing what women are capable of, I keep thinking, why are they not already running the world?

Which leads me to the calamitous state of our country.

Since the election of the fascist Gerald Reese as president, I have felt an unyielding anxiety most midnights, as I lie awake looking out into the dark. Often on those nights my thoughts turn to our classmate Frederick P. Reese II, who is not only the spoiled son of this abominable man but his most trusted political adviser, the one whispering in his ear, guiding his every morally bankrupt move.

Our college’s motto, Veritas, had never been his creed, and now, thanks to him and his father, we have all been forced to live in a post-Veritas world. Who knows if Frederick will brazenly choose to show his face among us on reunion weekend. If he does, I vow that I shall say to his shiny, boyish face what I write here:

Shame on you, Frederick Reese.

Prologue: Mariam

Dawn on Sunday morning of Reunion Weekend

(May 27, 2018)

Her daughter had just fallen back asleep in the crook of her elbow when Mariam noticed the man on the bench in the courtyard below.

It was very early morning. She’d been up for over an hour, rocking her toddler as if she were a baby, mumbling snippets of lullabies, her eyes slowly growing accustomed to the dark outside. Her arm had gone numb from the weight of Eva’s head.

From the attic room in Kirkland House, she had a view of the enclosed garden quadrangle, which all the windows of the elegant redbrick undergraduate residence faced.

Mariam smiled to herself when she saw the awkwardly angled silhouette of the man’s upper body. He was going to have a very sore back later today, when he awoke from his drunken stupor on that bench. They were almost too old for these antics. Behind her, in the narrow single bed they were sharing, just as they had through their years of dating in college, Rowan was passed out with the same oblivion, clutching a pillow to his chest as if it were a life raft, his hot rum-and-Coke breath making the air in the small room smell tropical.

In the other single bed, her older daughter slept the enviably deep sleep of a 5-year-old. Ah, to sleep like a child, or a drunk!

Mariam was dying of thirst – the post-alcohol kind, which no amount of water can satisfy. Normally Rowan would be the one settling Eva; with both girls he had taken on the diaper changes, the soothing, the settling. They’d made a commitment to divide the night load straight down the middle, but he had always tried to do more than his share, aware that during the day, as the stay-athome parent, Mariam carried the full burden.

But for now she wanted to let him sleep, after what had happened at the reunion dinner-dance at Winthrop House the night before.

She’d been astonished to see him like that, breaking loose, letting his appetites surface. It had been a shock, at first. Then it had been thrilling to be reminded that he, too, had other selves he sometimes kept secret from her. That there were still mysteries for her to solve, after all their years together.

If they’d been at home she would have let Eva cry for a bit longer, but as soon as Mariam had heard her whimpering she’d leapt out of bed to pick her up from the crib. For Jomo’s sake, and Jules’s, too. Jomo was in the room just down the corridor, within the same senior suite, and Jules was in the room closest to the door out to the landing. If either of them needed the bathroom, they had to tiptoe across the room in which her whole family was sleeping (or not sleeping), but that night she hadn’t heard them come through once.

It had been a long time since Mariam had shared a bathroom with people who weren’t family. The evening they’d all arrived, Thursday, it had been a fun game to negotiate the use of the shower and toilet, just as she and Jules had done back at college as roommates. It was easy to romanticize communal living when it was no longer your daily reality. But the novelty had worn off fast. On Friday morning, she’d been busting for a pee and had to hold it in with her sub-par pelvic floor while Jomo shaved, shat, and took a long shower. How selfish the childless could be!

While she rocked Eva back to sleep after her night terror – which was so much worse than a nightmare, her eyes wide open, not awake but not asleep; why had nobody warned her about these before she was a parent? – Mariam was trying to figure out how she felt about the fact that Jomo was not sleeping in his room alone.

His door was closed, but Mariam knew someone was in there with him. She’d heard scuffling sounds a bit earlier, familiar from those long-ago years of close living, when it had been normal to listen to other people having sex and think it was no big deal. Once, in their junior year, Eloise had brought back a guy who had kept going at it for three hours. Mariam had sometimes wondered if that’s what had turned Eloise off dicks forever.

It wasn’t exactly surprising that there was a woman in Jomo’s room. This had been his standard behavior at college, a new woman every weekend after some party at the Spee. He was a good person, so this wasn’t as sleazy as it sounded. He was just so very attractive to women. It was almost like a public service he provided to the opposite sex, to be that hot, that charismatic, that talented at playing singalong tunes on the piano, that creative, and also so respectful, someone who genuinely enjoyed the company of women . . . it was too much for most girls to bear.

Plus there was the fact that he was best friends with Juliet Hartley, the most famous person in their class. They all wanted to get closer to Jules through him, perhaps, though they couldn’t have known that he was in fact the barrier denying them access to her. Mariam suspected that Jomo had charmed the room on all those social occasions in order to give Jules a break from the spotlight that shone on her relentlessly. Jomo had been the insulating force, absorbing every bit of negative energy he could before it affected Jules. Those other girls must have known how it would end, that they wouldn’t be the one. Yet they’d all greedily taken whatever he’d offered them of himself.

It wasn’t that Mariam felt bad for Jomo’s current girlfriend, Giselle, either. They’d only met her a few times, though Jomo and Giselle had been together for a year and a half. She got the impression Giselle didn’t exactly love hanging out with Jomo’s old college friends.

But she and Rowan had tried to make an effort to get to know Giselle better, and persuaded Jomo to bring her to their place in Bushwick for Thanksgiving dinner the year before, when they’d stayed in the city for the holidays.

Jules had come too. She was about to go overseas for a shoot, she’d said, though there had been nothing in the celebrity magazines about upcoming films she was starring in (Mariam checked them regularly because she still didn’t like to ask Jules too many direct questions about her work life). Jules had brought gifts for the girls that were beyond their wildest imaginings: tiaras from the set of Sleeping Beauty, and a life-size toy Olaf, the snowman from Frozen, whom Jules had pretended was her date.

When she wasn’t entertaining the girls, Jules had seemed tired, maybe from the effort of preparing for the new film. Mariam had felt glad to be doing something to cheer Jules up, feeding her a home-cooked meal in an environment where she could let her guard down.

Like all of Jomo’s past girlfriends, Giselle was gorgeous, and she’d made every effort with her appearance that night, while Jules had made none. Sitting on opposite sides of the dinner table, they had looked like Rose Red and Snow White (and Olaf their idiot brother): Giselle with her red lips, and glossy dark hair matched to her shaped eyebrows; Jules with her alabaster skin, her white-blonde hair sticking up at the roots – she’d put no product on it – and her lips slightly dry from the late-fall weather.

Jomo had made a joke while he was carving the turkey, and Jules had guffawed in response (it had been the thing Mariam immediately liked about Jules when they’d first met on move-in day as freshmen: such an ungainly laugh from such an exquisite being!). Giselle had seemed puzzled – she was Italian, and, though her English was good, she’d missed the context of Jomo’s joke. Seeing him laugh with Jules, she’d looked threatened, which was another common trait of Jomo’s girlfriends. They could never get their heads around his being best friends with a woman like Juliet. Over the previous summer, Giselle had done everything in her power to prevent Jomo and Jules from making the trip to Tanzania that they’d planned to do together since college. She’d failed to stop them, but Mariam presumed Jomo had paid a price for it for months afterward.

No, she couldn’t care less about Jomo cheating on Giselle.

But she was jealous of Jomo’s return to a carefree, careless existence. His mother had lived. He got to sleep with sweet-smelling strangers without any guilt. All was right in his world.

She and Jomo, at first, had bonded over their parents’ cancer diagnoses. But when it became clear that Jomo’s mother would recover and Mariam’s father would not, she had felt betrayed by providence. She didn’t need any more lessons in humility or a deeper awareness of how precious time was. That was the daily stuff of her life as a mother, a wife, an educator, a daughter. All she did was care for others, count her blessings, check her privileges, give more of herself away.

Her father should have survived. What reward was there for her dutiful behavior if not that? What was the point of being good every moment of her life if things went wrong for her when it really mattered?

Outside, the light was changing. Mariam could just make out the Kirkland tower’s white wedding-cake tiers topped with a green dome and gold cross. The sky had turned a shade of lemon. She felt her spirits sink. It was already dawn, and she had slept for what – two hours?

It was going to be a long day. Soon she’d have to drag herself and Rowan and the girls to the final reunion event, the farewell brunch at Quincy House.

At least there would be waffles, the crispy ones with the Harvard crest imprinted on them. In spite of their bland flavor, these had been Mariam’s treat every Sunday morning at college. It had always felt as if she were ingesting the spirit of Harvard itself as she chewed on the crest, as if, with every bite, she became a teeny bit smarter.

And there would be bacon. Lots of bacon.

After last night’s shenanigans, though, perhaps it was better that she and Rowan go straight to South Station for the Acela back to New York.

She wasn’t sure who had seen what, and by then people had probably been boozed up enough to not notice anything, but still. Some part of her relished making a dramatic final impression on their classmates and then disappearing into thin air, not to be seen for another five years. For anybody who had noticed her and Rowan’s small but passionate marital drama, it would be a let-down to see them standing in line in the dining hall the next morning, wrangling their kids, looking haggard.

Yes, they should skip the brunch, she decided. No more chitchat with people she only half-remembered, no more asking and answering the same things over and over. She and Rowan would vanish, leaving a frisson, a question mark, hanging over their names.

She looked down at her daughter’s face, which had gone very pale – a sign she was in a deep sleep. Eva’s black curls, identical to Mariam’s own, were matted with something sticky, probably the lollipops she’d used to bribe the girls to go to bed before the babysitter arrived (the trick had not worked).

By force of habit, she began to compose a haiku about watching her daughter sleep:

A tiny blue vein

pulses at her right temple

She paused and looked out the window again, searching for the right words for the last line.

The man on the bench had not moved.

In the yellow dawn, she could see his face clearly for the first time. It was Frederick Reese. There was foamy vomit all down his tuxedo shirt. His eyes were wide open – just as Eva’s had been in the grip of her night terror.

Much later that morning, the proper emotions would swell in her, the shock that a person had died under her gaze, perhaps at the very same moment that her daughter had descended into a dreamless phase of sleep. But in that first moment of recognition Mariam felt only relief. The president’s son was dead. Somebody had finally taken a stand.

Chapter 1: Jomo

Thursday morning of Reunion Weekend

(May 24, 2018)

The turbulence was worse than any Jomo had experienced. In London, the plane had soared up into blue skies, but soon after, through his window, he’d seen the electric storm approaching, the lightning soundlessly stabbing the clouds beneath. He had never seen lightning from above the cloud layer before – down on earth, it felt as if it came from the clouds.

When the ride got really bumpy, he took a few photos, hoping to tame the sight by snapping it for future upload to one of his three social media feeds (recently pruned down from five). Morsels of life, packaged and presented at a safe distance. If only he could post them online now, nothing bad would happen to him; his plane would not go down.

He clung to his armrests. The rush he’d felt when called to board first – taking a left to the front of the plane instead of back to its rear where the masses huddled elbow-to-elbow – had long faded.

He wished he hadn’t felt that rush. At least he wasn’t upstairs, as he used to be on most flights. One of his resolutions made during the bad times in recent years – now over, thank God – had been to never fly first class again, no matter how well his company was doing, because of the feeling it fostered of being at the top of the human pyramid, like a pharaoh, looking down on everybody else. It had definitely affected his ability to empathize.

That false sense of being able to cordon yourself off from life’s hardships was what made wealth so appealing, and so disorienting. The first time he’d flown first class, for instance, he’d been surprised to find he was as jetlagged as usual upon arriving in Europe: as if spending that much money on a ticket should have insulated him from the physiological effects of jumping time zones.

The tin can in which they were all hurtling through the sky lurched sideways, down, and sideways again. The man in the adjacent seat had pressed the button that raised the partition between their pods as soon as he sat down, which normally Jomo didn’t mind; it was the point of traveling business class to be undisturbed by anybody’s needs but your own. Yet if the plane spun to the ground in a ball of flames, it would be impossible for Jomo to see over the partition to make eye contact with another human as they approached death. He began to wish he were sitting in economy, so that he could huddle together with the other people in his row, holding hands, screaming their lungs out together.

Jomo pushed the button to lower the partition a fraction. The man next to him was fast asleep.

He considered trying to call Jules from the satellite phone. A single call would cost more than his airplane ticket, probably. She would be flying into Boston too, from LA. She wouldn’t answer. It would go to her voicemail, set up as an automated voice reciting the phone’s number as safety from stalkers, and also because she couldn’t be bothered recording a new message every time she had to change numbers – he wouldn’t even hear her voice one last time.

Maybe she already had a new number, and had forgotten to tell him. It had happened before. Those awful few months at the start of last year when she’d been out of reach, when she’d failed to give him her new number, her new email address, and her new, snarky agent had refused to pass on any of his messages. He had tried his best to understand that she needed to take a short break from him, from their friendship. Yet he was still healing from the hurt of those lost months.

Their trip to Tanzania the previous summer had helped him feel less bruised – as had thinking they were going to die in that tent at Ngorongoro. He smiled, remembering the murderous bushpigs. And the feel of Jules’s entire body pressed up against his in their mindless fear. They had lain so still at the center of the tent, their racing heartbeats had become synchronized.

The plane dipped.

To distract himself, he considered the weekend ahead. It had been Rowan’s idea that they all stay in Kirkland House, always an option for returning alumni who wanted to slum it in undergraduate housing for their reunions, pretending they were back at college. Eloise had used her influence as Faculty Dean of Kirkland to arrange for them to stay in the same suite that she, Jules, and Mariam had lived in during their senior year. There would be alumni staying on other floors of the same entryway, but nobody else on the top floor, to give Jules some measure of privacy.

The plane dropped another foot in the air – Jomo closed his eyes – and then leveled out, as if it had got something out of its system. The air within the plane, and around it, too, seemed to settle. After a few minutes, the seatbelt light was turned off, and the flight attendants began to pamper their charges, offering to pull mattress toppings over their seats and handing out pressed pajamas. The cabin supervisor went around refilling cocktail glasses with a rueful expression on his face, as if British Airways were responsible for the bad weather. The mood lighting was switched on in the cabin, making the silver pods glow pearlescent. It felt as if they were in a spaceship on their way to the moon.

Jomo rubbed his hands together to ease the strain of his white-knuckled grip on the armrests. On his right palm were ink smudges, left there by a palm reader the day before. His hand tingled, remembering the old man’s dry touch, his careful inspection, and his final, solemn words.

Jomo had gone to Cecil Court, a Victorian alleyway in central London, because he’d been tipped off that an antique-books store there had a rare gem collection.

Outside one of the buildings was a blue historical marker: Mozart had lived there around the time he composed his first symphony, while his father was ill and he and his sister were forbidden from playing the clavier (Mozart had turned to drums and trumpets instead). It was the kind of detail Jomo’s piano teacher from back home would have loved – she’d always tried to humanize the composers of times past, so that the music didn’t seem like it had dropped from the ether.

The store was called Rawlings Books. Velvet curtains hung in the windows, and on the door was a list of the shop’s wares: Perennial Wisdom, Crystals, Mala, Oils and Incense, Tarot, Singing Bowls.

If only it were as easy to come by perennial wisdom as to purchase a few crystals or singing bowls, whatever those were.

Inside, the shop was lit with candle chandeliers (a fire hazard, the businessman in him noted). A few people were browsing books in the dusty stacks. At the checkout counter, a woman dressed in leopard print began to stare at Jomo intently. Typical, he thought. A tall black man approaches and all the hippy-dippy, love-everyone shit goes up in smoke.

But for once, his own assumptions were wrong.

‘I’ve never seen a true magenta before,’ she said to him. ‘Your aura. It’s remarkable.’ She blinked, as if a rainbow were emanating from his head.

The owner was overseas, he’d soon learned, and the woman didn’t have access to the vault where he stored the gems – though she’d heard that he had a genuine Mexican fire opal in there, affixed to an Aztec idol.

Dispirited that things were not going his way, Jomo had glanced down and seen a handwritten sign on the desk: The Swami Is In.

‘I want to see the swami,’ he said.

‘Sorry?’ she said, leaning forward.

‘I want to see the swami,’ he said again.

‘I’m terribly sorry, I can’t understand your American accent.’

‘I WANT TO SEE THE SWAMI,’ he said loudly, attracting looks from a couple of the book-browsers. He was wearing a suit and tie, and probably did not look anything like the type to come into this store on a weekday to ask for spiritual guidance.

‘He doesn’t have access to the vault either, I’m afraid.’

Jomo said nothing.

‘Ohhh, right,’ she said, finally clicking. ‘Forty pounds for thirty minutes.’

He counted out the notes.

‘Follow me.’ She took him up a flight of stairs, to the second level of the store.

In the sunlight coming through a stained-glass window, at a table covered with a red tablecloth, an elderly man sat sleeping. He was wearing spectacles and had trimmed his beard too much on one cheek, so that his face looked lopsided. Jomo immediately regretted his impulse.

‘Swami . . .’ the woman said.

The swami opened his eyes.

‘This man would like to see you. For a consultation.’ The woman then retreated – backward – as if it would bring bad luck to turn her back on the swami.

Jomo struggled not to laugh.

The swami caught Jomo’s eye and smiled; he was in on the joke. ‘Please, sit.’

He asked Jomo a few questions, his date of birth, his first and last names. ‘You are 37 going on 16,’ he said, with no further explanation.

Then for a long time he said nothing. He took one of Jomo’s hands in his own and studied his palm.

It had been an early start that day for Jomo, a busy round of morning meetings and an auction at Christie’s where he’d successfully bid on a diamond necklace once owned by Elizabeth Taylor.

He must already have had four cups of coffee, but in the early-afternoon slump, his caffeine buzz had worn off. He relaxed. There was incense in a brass holder, and it smelled good, like orange peel and musk. Birdsong, and wind-chime music, reached his ears from the room’s speakers. It was pleasant to have his hand inspected closely, as if the answers to his questions had been written on his palm all along.

The swami was pointing with his pen at the crease across Jomo’s palm. ‘You are a creative,’ he said. He prodded the fleshy base of Jomo’s thumb. ‘A strong Venus aspect. You believe in true love.’ He followed a line up to Jomo’s index finger. ‘Yet you are unmarried. No children. No desire for children yet.’

The pen slipped on the thicker skin pads at the base of Jomo’s fingers – signs of the wear and tear of life. He’d never properly appreciated his hands, except perhaps while he was playing the piano, but even then, they felt like nimble tools of his brain, not special objects with clues to his future etched on them.

Jomo gestured to a line that forked into two near his wrist. ‘What does that represent?’ he asked. ‘Is that my lifeline?’

‘It doesn’t really work like that,’ the swami said kindly. ‘It would be like asking what a letter means without seeing the word.’

‘I’m going to die young, is that it?’

‘Strong, strong, ninety years or more . . .’

He squeezed the muscle between Jomo’s thumb and forefinger. ‘You are confused by what fidelity means. That is society’s problem. It is not your problem.’

Here we go, Jomo thought, the spell lifting. Next thing he’s going to ask me to join his crazy sex cult.

‘My teacher says that to learn to love is the greatest art of all,’ the swami said. ‘I don’t mean desire, not sexual desire. Learning to love is difficult, Osho says, because it requires diving into your own soul. Osho writes that without self-love, one cannot find the clarity to love another.’

Jomo shifted in his chair. Who the fuck was Osho?

This self-love speech was not what he’d come for. His problem was the opposite; at times he was blinded by his own self-regard, while pretending to have all the same doubts everyone else did.

Take his entry for the fifteenth anniversary Red Book, the class report. It was humble, so that his classmates would continue to like him, though it had always been obvious to everyone who knew him that his lucky stars rarely stopped twinkling. Even when his mom had been really sick, he had known she would get better: of course she would. That was just how things went for him. He was proud of being well thought of by his peers, yet he also knew it was easy as pie to be gracious when you were on top.

He had so effectively repressed his only failure to get what he wanted that he did not ever think about it in his waking life. Very rarely, he’d have a dream of a life with Jules where they were no longer just friends that was so vivid, he’d wake to discover his face was wet with tears.

The swami seemed to sense that he’d taken a wrong turn. He spread out a battered pack of Tarot cards on the table before Jomo. ‘Pick one, but don’t look at it.’

Jomo obeyed, and the swami laid it facedown before him. ‘Another.’

Jomo picked six more cards, and the swami arranged them into a pattern. He turned over the first card. On it was an image of a hand coming out of the sea, reaching for lung-like creatures in the sky. Cutting Through was printed at the bottom.

‘This is your past,’ the swami said. ‘A sky card. Ambition.’

He turned over the next one. It showed molten lava beneath black rock, and was captioned Fire of Sacrifice. ‘This is your present. Fire. Also ambition.’

Jomo decided to be difficult. ‘But it says Fire of Sacrifice. How is that about ambition?’

The swami shrugged. ‘Trust me. Fire means ambition.’

He turned over the next card. It showed a pink lotus flower on a pond. ‘This is your future,’ he said. ‘It is about creativity, but also control. You work for yourself; you are your own boss. You most likely always will be.’

Jomo gave no sign the swami was right. The lotus had spiky petals. Looking at the images made his head feel funny, as if they had real power over his unconscious. It was hard to look away.

The swami turned over a card set to one side. ‘This is your greatest fear,’ he said. It showed an Egyptian mummy on an alien planet. Self-Preservation, the caption read. ‘Loneliness. You fear it more than anything else,’ the swami said. ‘See how this figure is so wrapped up in itself, it cannot be unbound?’

The next one was captioned Mother’s Milk, and had disembodied nipples spurting milk against the backdrop of the galaxy.

‘This is your wish,’ he said. ‘You would like to be a nurturer. It doesn’t have to be as a parent. But it comes back to what I said earlier: you have not been able to find intimacy and desire – love and sex, if you like. Always one or the other.’

Jomo thought of Giselle. She was so beautiful. So desirable. But was she really lovable? Was he?

‘And now, the last two cards,’ the swami said. One showed a bird’s wing made of metal, and was captioned Just Passing Through. ‘This is the key to your heart’s desire. Interesting!’ He looked up at Jomo. ‘This is a freedom card. You do not feel free, and you will not attain your heart’s desire until you do.’

When the swami flipped over the final card, he gasped. It was clear what it represented, even to Jomo: two red apples mirrored in water, and a green snake slithering between them. It was captioned Temptation.

Jomo studied the swami’s face – was this concern on his behalf part of the act?

‘Your heart’s desire is for something that is almost certainly out of your reach,’ the swami said. ‘So you have a difficult decision before you. Stay in your chains and keep all you have – or make yourself free and risk losing everything.’

The session was over, but Jomo couldn’t find the energy to move.

The swami pushed his spectacles higher on his nose. ‘The people who come in here are seekers,’ he said. ‘For many others, life passes them by. They eat, sleep, work, watch TV, but they don’t ask why. They don’t ask, What is the point? It is good you are asking, even if I cannot answer the way you might have wanted me to.’ His tone was apologetic.

Jomo instantly forgave him. Of course he couldn’t answer the eternally unanswerable questions: Who am I? What will happen to me in my life? He was surprised by how quickly he’d been prepared to cede authority to a kindly old man turning his hand this way and that, making vague statements that he knew Jomo would connect up to real people and events in his life. It was an illusion of wisdom, yet it was still comforting. He could have sat there at that little table all day.

‘You have the ring already,’ the swami said, out of nowhere, as Jomo got up to leave. ‘It holds a mauve gem, in the shape of a teardrop.’

Like any good magician, he had saved the best for last. ‘She is waiting for you. She has always been waiting for you.’

On the plane, Jomo dug about in the back pocket of his chinos for the ring he’d been carrying around for several months now. Like the pea tormenting the princess, he could often feel its form when he was sitting down. It wasn’t even in a case. Just the ring, loose, as if it had come from a box of Cracker Jack.

He was tempting fate to take the ring away from him, to make the decision on his behalf. Why else would he play a form of Russian roulette with a ring that meant as much as it did? A yellow-gold band holding the musgravite gem that his grandfather had sourced in Tunduru, Tanzania, for his grandmother, long before anybody knew that the mineral was one of the rarest on earth.

A few months ago, Jomo had almost proposed to Giselle with that ring, in their favorite restaurant in Aspen, basking in the warmth of the log fire, his body aching from a day of skiing and – let it be said – fucking.

When she’d excused herself to go to the bathroom, he had dropped the ring into her glass of wine. As soon as he’d done it, he knew he had to fish it back out. He’d envisioned her swallowing the ring by mistake, in one big gulp, or choking to death on his family heirloom.

The waiter had given him a disapproving look as Jomo downed Giselle’s glass of wine and caught the ring in his teeth, but he’d cooperated in the cover-up, refilling her glass just in time for her return.

Jomo knew she’d been disappointed at the end of that holiday, though she hid it well.

The irony was that strangers had already proposed to her – in Italy, to be fair, where the men were totally insane. In the Piazza della Repubblica in Florence, a man had dropped to his knee and pulled his (dead) mother’s wedding ring from his wallet. Jomo had thought Giselle must know him – that he was an old flame – but she swore she’d never laid eyes on him. He hadn’t known whether to believe her until it happened again, in Rome. On both occasions, when she’d declined, the men in question had turned to Jomo and made a sound of pure disgust that he had not yet made this woman his wife.

Why hadn’t he? It was hard to explain. Even in their most intimate moments, he felt an undertow of loneliness.

At first, he’d thought this was a function of their different cultural and language backgrounds. But over time, the shield had stayed up, even after that trip to meet her family in Italy. He’d begun to wonder if it had more to do with them being temperamentally incompatible. Take their skiing trip. On Christmas Eve, in bed in Aspen, watching the snow fall outside, darkness onto darkness, her head against his shoulder, he had felt nothing but desperately alone.

Whenever he tried to talk about it with Giselle, she would get confused by his mixed messages, and it would make the problem worse. It was unfair for him to do this, to ask the person he loved, ‘Do you also feel a little lonely when we’re together?’

It was possible that he was the problem. All those years of buffet-dating, choose-your-own-adventure relationships. He’d had too much choice, for too long. He just needed more time to adapt to life in a bonded pair.

He was of an age where he was beginning to stick out for being unmarried. It was no longer considered a sign of him wisely taking his time but as a problematic inability to settle down. He’d noticed business associates changing their demeanor on seeing no ring on his finger, on hearing him say ‘my girlfriend’ rather than ‘my wife’. A man approaching forty who is unmarried is a wildcard, and those in stable relationships were increasingly wary of Jomo, as if being around him for too long would spread havoc in their own lives. He was patient zero of a disease they did not want to catch.

The swami’s message to him was simply the latest in a series that all seemed to be saying the same thing: Commit to the woman who so clearly wishes to commit to you.

For instance, on his first day in London, he’d gone for a run through Hyde Park, and ended up in a meadow filled with wildflowers. The rest of the park was so stately and ordered that the overgrown meadow surprised him for seeming out of the national character.

He’d sat down on a patch of springy heather for a rest and seen a small airplane writing letters against the sky, which began to shear and blur, erased by the elements, as soon as they were formed: M-A-R-R-Y M-E.

Giselle deserved a grand gesture like that. She deserved somebody who shouted his adoration of her to the world.

She had been rightly offended on discovering that he hadn’t even mentioned her in his Class Report entry. He had tried to explain (lamely) that if he’d mentioned his stunning, talented Italian girlfriend, who had already designed her own handbag line, it would come across as grandstanding, the wrong tone for the fifteenth-anniversary report, when his classmates’ entries would be more tempered with modesty as they approached early middle age.

She’d eventually written off his failure to mention her as another quirk of American culture that was beyond her understanding. Then she’d forgotten about it entirely and said yes to a hens’ weekend at Cape Cod for one of her friends, over the same dates as the reunion. Jomo had pretended to be upset about this, but he’d felt relieved. And then guilty about feeling relieved that the woman he might one day marry would not be by his side at his reunion.

The part about getting his tone right in his entry was true, at least. He’d worked a bunch of jobs through college, one of them at the Harvard Class Report Office, helping the four full-time editors collate and edit the alumni anniversary reports, colloquially known as Red Books because they were bound in crimson covers. They had been published by the university for around 150 years – the earliest versions dedicated only to deceased classmates but gradually changing focus over time, becoming a way for classmates to self-report on their lives in whatever form they chose. Some people wrote long, painfully earnest entries; others wrote light-hearted limericks.

His responsibilities in that job had included spell-checking and fact-checking the entries. ‘Don’t let Team Harvard down,’ his boss had said. People left out children and spouses, added degrees they’d never finished, invented companies they worked for or job titles they held. Sometimes Jomo had to flag things as potentially libelous (angry rants about very specific wrongdoings of politicians, for example, or insults hurled by classmates still caught up in some old college enmity).

These were reminders of the depressing aspects of human nature, but there were upsides to the job too. Jomo had enjoyed tracking how the tone of the entries in each report was usually the same, as people’s lives followed similar general patterns. The five-year reunion updates were mostly open boasts, about consulting jobs and law school and exotic travel. The ten-year updates were mostly veiled boasts, about getting married or published or founding start-ups or charter schools.

At the fifteen-year mark, the tone began to change. The entries were split between those who kept going with the charade of their lives being perfect and those who were ready to tell it how it was. People wrote of becoming parents either with overstated happiness or with an admission of being unprepared for the passionate drudgery of raising children. Some wrote of being promoted; others confessed to having been retrenched. The startling honesty of some of the entries was the first intimation that whatever unique status Harvard had once conferred on them had long since worn off.

And Jomo knew already what was in store for his class in the years ahead. The twenty-fifth Class Report would be harrowing to read: divorces, kids who had lost their way, foreclosures, health scares. Worse, it was one of the few reports that allowed people to include photographs – one from college, one from their current life, which could sometimes feel like rubbernecking at a gruesome car accident. But the interesting thing was that people’s experiences of hardship seemed to make them nicer, funnier, more open. And lighter, as if by laying down their sense of being special they had put down a heavy load they were tired of carrying.

That was the case for the fortunate ones, anyway. The survivors. For in every anniversary report, the In Memoriam list at the back of the book would grow ever longer.

Jomo took out his copy of the fifteenth-anniversary report from the satchel at his feet. Thus far, the Class Report Office had stuck to their vow never to publish the reports online, so although it was bulky, he’d packed it for the reunion in case he needed a reminder about people’s names and vocations, and whether they had partners or kids.

The list of names at the back of his class’s report was still short. This made it heartbreaking and also somehow more ominous: there was so much blank space there, waiting to be filled. There was something about the middle names of his deceased classmates, none of whom he’d known personally, that particularly moved him. Bound up in that middle name was all the hope of parents bestowing on their newborn baby names with personal or familial significance. A middle name was inward looking, unlike a first and last name. It was usually only revealed at birth – and at death.

He turned to the front of the book and skimmed a few entries. Most were fairly traditional updates, but there were always outliers. Someone had written a short story about himself in the third person. One entry was a numbered to-do list. Another was a humorous open letter to the classmate’s parents, apologizing for not properly appreciating them until now.

One entry caught his eye, because it was formatted as a poem. He recognized the name of the woman who’d written it. She’d been a member of the Kuumba Singers with him at college; he remembered her soloing for the version of the Lord’s Prayer in Swahili that he’d composed and arranged for the group to perform at one of their end-of-year concerts. His father had helped him with the translation, and they were still pretty much the only bits of Swahili that Jomo knew. Could he still remember them? He pictured the lines in his mind’s eye, so the guy in the pod next to him didn’t think he was a terrorist muttering prayers.

Tunachohitaji utusamehe

We need you to forgive us

makosa yetu,

our errors,

kama nasi tunavyowasamehe

as we do forgive those

aliotukosea. Usitutie

who did us wrong. Don’t put us

katika majaribu, lakini

into trials, but

utuokoe na yule msiba milele.

save us from this distress forever.

The soloist’s short, devastating poem was titled ‘Waking on the Morning of November 9, 2016’. It described her dawning awareness that, with Reese elected president, she would be forced to live in a world that she had been told by trusted elders was long gone and could not be resurrected. It took many others – those who did not know fear firsthand – much longer to read the writing on the wall, she wrote in the Class Report. Not me. It used to be a treasured gift, to see into the future. I have closed my third eye forever.

At the end of the poem she named and shamed Fred Reese, the president’s son and adviser, as some of their other classmates had too. Jomo wished he’d written something like this for his entry. He had not even contemplated bringing politics into his; he’d gazed at his own navel, at the smallish contours of his life.

He finished off the icy dregs of his vodka tonic. On his most recent visit to the doctor for a check-up he’d been told that – though he thought of himself as being in excellent health – his blood pressure had gone up; he blamed that on the Reese administration.

The air steward appeared at his side to refresh his drink. Jomo wondered if this man despised having to wait hand and foot on him. Did he fantasize about murdering everyone in business class with a butter knife?

This line of thinking could do no good for his blood pressure.

Jomo remembered feeling a strange envy for the elderly Harvard cohorts celebrating their fiftieth reunions and beyond. In their Red Book entries, they were no longer hustling to make something of themselves. They’d turned around and were looking steadily back, misty-eyed. So many of them wrote much the same thing: Did I go to Harvard? Did that really happen to me?

Why would he feel envious of anybody so old?

The insight gave him actual heart pain, like indigestion of the soul: it was because all their burning questions had been answered.