9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

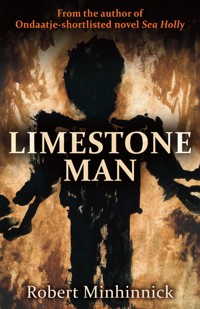

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Richard Parry is a painter who cannot paint, a writer who doesn't write. His obsession is Lulu, that 'orphan off the street', his aboriginal 'green child'. But on returning from Australia to his hometown he finds it has become notorious for the suicides of young people. As Parry tries to connect past and present he is haunted by dreams of Australia and of his youth. Yet is Parry all he seems? Isn't he frankly, 'a bit creepy'? How trustworthy is memory? And what has happened to the vivacious Lulu? A meditation on age and opportunity by prizewinning poet, essayist and novelist Robert Minhinnick. Limestone Man is this writer's second novel, after 2007's Ondaatje-nominated Sea Holly.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 396

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Contents

Title PageDedicationONETWOTHREEFOURFIVESIXSEVENEIGHTNINETENELEVENTWELVETHIRTEENFOURTEENFIFTEENSIXTEENSEVENTEENEIGHTEEENNINETEENTWENTYTWENTY-ONETWENTY-TWOTWENTY-THREEAcknowledgementsAbout the AuthorCopyright

LIMESTONE MAN

by

Robert Minhinnick

for Decima and Ffion

ONE

I

I’m trying to remember. The last time I saw Lulu.

I know her back was showing its white scar. That part of her back above her three black moles. Orion’s belt she called those moles. I used to wet my finger and trace her three black stars.

And then the scar. I always thought that scar resembled the shape of The Caib.

We used to joke about that. At least I thought it was funny. But yes, I did say something. Something likeThe Caib, remember. The Caib! You always ask where I come from. That’s where!

And maybe I slapped her. Like anyone would. No harm in that. A slap.

Back of beyond, she had said.

Not really, I said.

But then she repeated it. Like she always did. Which was irritating. Yes, Lulu could have that effect.

Backofbeyonbackofbeyonfbackofbe…

I must have been tired. Yes, tired. So I said something. And regretted it instantly.

Better than… I said.

She turned then.

Better than what? she asked.

Better than the Outback of beyond.

Yes, I remember that scar. Above the cleft of her arse. A seam of quartz in red sandstone, that scar. Look, it’s natural to slap. Someone there.

And we were tired. Not ourselves. The drought was over and we’d been celebrating. But we weren’t ourselves.

I remember the gold dust on her shoulders. On her vest. In her hair. Whenever someone went in the dunny, they came out golden. From the paint dust.We know where you’ve been!we used to say.

Next, I heard the screen slamming. And then her wail.

Oh, for goodness sake… I’d said. I think I said.

Can’t you..?

Take a joke?

Can’t you…

II

I returned to old haunts. For the first time since my …incident, I drove to Adelaide. Walked into The Sebel and booked a room. Winter rates.

No, I’d never stayed there before. But I felt I owed it to myself. First of all I listed the places I needed to try. It’s always lists with me, isn’t it? Names of records I should be playing. Records to avoid.

TWO

PARRY’S DIARY

MONDAY

I felt excited. Any minute now, I thought. Any minute now I’ll see that curly hair. That honey-coloured skin. Any minute now. How could she not be here?

I looked around the lounge, the marble pillars. Who’d left that drink at a corner table? It must have been Lulu. I even checked the Ladies.

But I avoided school and the chances of meeting staff. Didn’t want to see Libby or anyone else in the department. And I was determined to be gone by Friday afternoon. That was when a group of teachers went out drinking.

Old haunts, past times. I ordered malbec but it was bravado. The wine tasted sour. I had the bottle decanted and left in my room to breathe.

Yes, it was early. The barman gave me a knowing smile. Seen it all, hadn’t he? By 11am on a Monday I was already in the market at our favourite booth, a pot of lotus tea in front of me.

We’d drunk that sometimes on our city expeditions. The Chinese girl who worked there would put a lotus flower in a saucer of water on the table. But not this time. One cup only this time. And no flower.

I sat down and convinced myself again that Lulu had to be there. Nearby. The market was busy enough, full of the smells of cinnamon, cardamom, coffee. Everybody seemed to be doing something vital. Even if it was only sitting and waiting. There was a pattern to life. Everyone had a place and so did Lulu. Her place was in the seat opposite me. Her cup should have been the cup next to mine.

Lulu and I had this special way of saying goodbye. I’d saySo Long, Arcturusand she’d sayFarewell, Arcturus.Or something like that. After the star, naturally. Okay, sounds corny. But there you are.

Arcturus is a red star, moving away from us. In a couple of million years, Lulu had said, we won’t be able to see Arcturus. The sky will be different. Imagine it, she said. Our sky without Arcturus.

How do you know that? I always asked her.

Because I read it, Mr Teacher, she always said.

And I know where you read it, I always said.

In marvellous books! we said together.

So, so long, Arcturus.

I sat in the market. Everything seemed right with the world. There they were, the mums with pushchairs, the kids in their school uniforms, mitching off. The lonely, the lovesick, the lost. Particularly the lost, you learn how to spot them.

Yes, that barman in The Sebel gave me a smile. But he was sharing that smile, if you know what I mean. It said, we’re in this together. I know it and you know it.Sport.

Then a little Chinese girl came past, pushing a portable griddle of roasted ducks. Then a florist with a blue spike in a pot. Hyacinth, probably. Then two Chinese blokes arguing. And all walking past my table in that corner of the market. The Adelaide street, brimful, bountiful. This world as it came to me.

An hour later I was across the road in another café Lulu and I sometimes visited. This was a smaller place, almost under the Lion Gate at the market entrance.

It was lunchtime and I tried their wonton soup. I shared a table with an excitable couple, just married I think. But I was always looking round. Still searching for Lulu.

Two o clock, three. I’m still looking. The couple long gone. Only me in the café at 3.30, and there I am with green tea and more green tea. And a cake. I’d never tried Chinese cakes before but this was acceptable. No, maybe a little dry, even though it was green cake, soaked in green tea.

I remembered The Caib when Jack and Dora were together in the last year. Breakfast was what they calledsop. Bread soaked in black tea. They would sit in the kitchen with bowls of sop and look out at the garden. Like two refugees, I often thought. Sucking up that horrible food, stale currant bun, cold tea. But they loved it.

At that time in the garden there were usually as many sunflowers as Dora could coax into life. I used to think about those sunflowers. How like people they were. In their slow decline. Yellow and splendid, those sunflower faces. And crawling with bees. But soon bowed, even the sturdiest.

Mum would stake them with bits of bamboo, tied with rags. And every sunflower different. Yes, like people.

Then a break. Then more tea. Then a different cake. Then a walk down Gouger Street, then another tour of the market, both directions. Then five minutes back in the first café.

Five o’clock, I was in the Botanic Gardens and the tropical house. Surely, I thought. Surely. Who was that girl? Whose was that voice?

But there were too many people. Lots of university students, lots of lovers, the lonely, the lost. Everyone mooching about. Moochers, yeah, moochers. That’s what we do, isn’t it? That’s all we are. Wellmoochers graciasto us lost souls.

Long walk past The Sebel. Six o’clock, seven, and a decent crowd in the marble bar. It’s close to the theatre and there was a performance due. I went up to my room and tried the malbec. Better, I thought. At least drinkable. So I took the bottle downstairs and finished it off. A different barman.

I checked the grand staircase, then took the walk back to Gouger Street. In the market everyone was packing up. Back out to the Lion Gate café. But they were getting ready for the next day. Tomorrow.

Christ, I thought. Christ. What happened to today?

It was dark. I looked in the smart Indian restaurant. Don’t know why. Then the cheap Lebanese. Tried every bar with their attached gambling parlours. Tried the kebab queues, the places where Lulu had loved the wedges served with garlic mayo. But everything now was not right with the world.

Went back to The Sebel and sat where we’d always sat. And this time I tried the wedges myself, under a marble pillar at a tiny marble table. That marble cold as the quartz on The Caib.

Then maybe another red wine. Yeah, a crude and bloody Aussie shiraz. After that I sat in my room looking out at the city lights.

Always exciting, aren’t they, cities at night? On The Caib you hear the sea like a record crackling over its final grooves. But sometimes I miss the neon, those orange and violet shadows of Adelaide. And I stayed at my table thinking I should be out there. Out there…

TUESDAY

From six, I tried the bus and tram stops. Up and down Rundle and Hindley Streets. Why not five? The buses start at 5am. Cleaners gong to work, the people who make your coffee. All the nameless people? They start at five. They’re out there in the dark. At 5am.

Then the immigrants, the drifters? They’re out there at five. Before five. But I began at six.

And yes, I had a photo and asked around. Have you seen this girl? Please, have you seen this girl?

Went over to the YMCA. That’s a possible place, I thought. A likely place. Showed the photo at the desk and they said, yes, try the lounge. Special permission.

So I waited there from 9am. Watched those kids laboriously cooking breakfast. Getting ready. And I heard about all those places they’d been, remote outback, Papua, New Britain…

I thought surely someone was sleeping late, recovering from a sesh… Christ, I thought, Christ…

Not everyone was young. There were a few older couples. But everybody was interested and a few thought they’d seen her. One bloke was certain.

But then he started to doubt himself. He came back to tell me. No, he wasn’t sure after all. Could he see the photo again? Yes, no, he wasn’t sure. Any more. Could have been. Might have been. But possibly not. Maybe he was thinking of someone else… So hard to be… How old was the…?

Gradually everyone drifted away. Even those with books who seemed set for the day. By twelve I was on my own. Someone came to turn the telly off.

Then I walked over to the state gallery on North Terrace. I’d always loved that gallery. The paintings have room to breathe, and I’d taken Lulu there three, four times. Again, it was wonderful.

Maybe it was there I had the idea for my big canvas,Mother of Pearl. You know, ‘Morning on The Caib’. That’s my great idea. Told you. Told everyone about it. When I paint. When I paint my masterpiece.

Yes, all that space. Means the colours can breathe. Colours need to breathe, you see. Got to make room for colours. But there was hardly anyone in. Hardly anyone…

We’d seen a film there. But there had been better crowds for The Cockatoos I thought. Yeah, The Black Cockatoos. Again, I showed the photograph. Excuse me, have you seen, excuse me, have you… Please, could you look again, could you…

Over to the Mall and all those shops that Lulu pretended not to like. But of course, why not? Anyone her age. Anyone…

I’d have waited while she tried them on. New clothes, you see. That’s what she needed. Better than those… Yeah, show herself off. And changing rooms in the corner, a seat while you wait. Be the first to see her. I could have been… I could have been…

Look. Someone’s left that coat on the floor. No, it’s not, it’s not… But who chooses the music in those places? Who…

See, you have to think about your in-shop playlist. Says a lot. About you. About who you are. About who you think you are.

No, Miss. I’m just waiting. I’m just waiting for… Someone… She’s coming back. Any…

Minute now. Slice of pizza from a stall outside. Black olives saltier than green. Mushrooms sliced. Not enough mozz, not enough I’d say. Masses of mozz, that’s what Lulu liked. Real mozzquito was Lulu, those stones rolling, ungathering… The stones that filled my mouth…

Passed the Lebanese. Down the stairs. A brick cellar with nobody in. Make a great little jazz club, the Lebanese. Ornette, I thought.Miles Ahead.

Ordered a bottle of their own. Oily, black. The coming place, it said. Restaurant review photocopied and pinned with a stiletto to a beam. Yeah, a knife. Still quivering. As I live and…

Lebanon’s time is here, it said and why not? it asked. There are so many Aussies now with Lebanese blood. And we all have a time, don’t we?

I tasted the wine. Oh, I thought. Oh…

The Lebanese breads arrived, the hummus. Garlic, I thought. The white garlic bulbs, the purple skins of the garlic cloves.

I planted garlic once. Watched the shoots curl in winter. Out of the old fruits those little fingers.

Here’s themezze,I said to myself. In tiny bowls, as if they held paints.

And then,arak. The cleanarakto wash away the dark, the feculent…

Aharak. Its white fire. In the bottle with the milled glass stopper.

You eat alone? the man asked.

No, I said. Any minute now. Any…

But he commanded:

You.

Eat.

Alone.

WEDNESDAY

5am, the tram stops, the buses. Women hunched, men vacant. Who’s slept? I wondered. Who’s dreamed.

A group of native people were sitting in a corner of that park by the market. Tinnies not even crushed.

One of the men was lugging a fifteen-litre box of Henley’s Estate red. I showed them all the photograph. And, fair play, a few might have looked.

Yeah, one said. I know her. I know her.

How d’you know her? I asked.

I know her, he said again.

From where? I asked.

One of the women, seamed and haggard but maybe only twenty, in a ruined overcoat with gold braid on the shoulders, spat at my feet. Her gums were bleeding.

Lulu, I said. She’s called Lulu.

Yeah, Lulu, the man said.

Don’t you know? the woman hissed, bloody drool on her chin. Don’t you know? We’re all of us called Lulu. Look, I’m Lulu. She’s Lulu. He’s Lulu. Hey, mister, say hello to Lulu.

That earned her a laugh. Maybe I laughed too.

They’d made their camp under acacia bushes. Spread out on sheets of Panasonic cardboard. There was a loaf, a milk carton and a roll of toilet paper one of their kids had been playing with. All unrolled, that pink paper. Yeah, pink. All unrolled.

You know Kath? I asked. Kath?

Hey mister, the woman said. What happened to Lulu?

That broke them up. I know I laughed too.

Listen, mister, the woman said. Don’t you know? Did no one ever tell you? We’re all of us Kath. We’re all of us Lulu.

Kath’s older than Lulu, I said. But in my mind I was walking away.

Please, I said. Look at the picture again.

Yeah, said the woman, looking once more. You know who that is? You know who that is?

That’s… the man said.

That’s Lulu, the woman spat.

No, the man laughed. No, that’s…

Kath.

Then everyone was saying it. That’s Lulu, that’s Lulu. That’s Kath.

Have you seen her this week? I asked. Can you think? Please? This week.

Hey, tell me what day it is, boss, said the man. And I’ll tell you if I’ve seen her.

Half an hour later I was in the university library on North Terrace. My card dated from teaching days and I remembered clearly where I had to go.

The reading room was full of yellow light. I wondered, as I had been first in line, how the other readers had entered. There were already three men standing behind the desks. Men my age, I suppose. But older looking, surely. Older than me. Everyone else was stereotypically a student.

Students seemed younger than I recalled. I thought of hairy, bearded men. With something to say. These kids seemed pallid, even bloodless.

I found the latestAstronomy Todaywhere I knew it belonged. Magazines weren’t date-stamped but this edition, brand new, didn’t look as if it had been consulted, even opened. I raised it to my nose. New glue of a fresh edition.

On the cover was a galaxy inside the darkness of space. So many lights. Each light a star or another galaxy. So many lights…

I think of the quartz in the caves at The Caib. That quartz with the sun on it. Like stars, I’ve thought at times recently. That orange-red of Arcturus, the blue and orange of Albireo. As if the quartz had fallen to earth. To shine a moment in cave gloom. Stars trapped in stone. Fossils of starlight.

So here I am, I said to myself. What do I do now? I was trying Facebook. I was trying Bebo. But I thought what I’ve always thought in the library. That I have lived my life without studying physics. Without understanding mathematics. That I’ve spent too long with pictures. Too long with poems and plays. With other men’s art.

In school, in fact, I’d hated physics. If only…

But it was the same with the guitar, the piano. The failure to persevere. Nicky Hopkins played on thirteen albums by the Stones. He was waiting for the call and Keith always called. Nicky was ready. But I…

My right hand still felt cold. Ice at the fingertips. As if I had cupped water from a rock pool. Yes, the hand was still traumatised.

When I looked round again, there was Sophia, crossing the reading room. Sophia, who helped sometimes inHey Bulldog.

Well… I said. Well…

Fancy meeting you, she continued. Here.

Here, I said. Yes, here.

Oh, she said. You’ve stopped shaving. Maybe…

And I stood. Looking at Sophia’s hair. She must have done something to her hair. There was a blonde kink in her hair. Now. Surely that kink was new. The colour was different.

Sophia seemed older, more confident somehow. At least more adult. But people change. Only the dead stay the same.

How’s the writing? I asked.

Great, she said. Sometimes it seems like it’s not me doing it. The writing, I mean. It feels that I’m being written. Does that make sense?

Yeah, I said. I suppose that’s how everyone feels. Eventually. Listen…

Yes, she said. I expect…

Listen. Have you seen Lu?

Sophia looked at me then. I felt I was being appraised.

No, she said finally. Not since before the rains. But I’ve been away. Lucky you caught me. Why?

No reason, I said. Just thought Lu might be up here. She loved this library.

She’s been getting tired of Goolwa, nodded Sophia.

You think?

Oh yes. Everybody gets tired of that place. Like, who wouldn’t?

Yeah. I know what you mean.

Yes, she said.

But no reason, I said. I was just… I was just…

Wondering? she asked.

I looked round the main refectory while I was waiting for our coffees. We’d both decided on chocolate bars. I also had a plate of biscuits.

So, the lyrics are…

The songs, she corrected. The songs are going pretty well. I feel playing those sets in the shop brought me on. You know. Confidence wise…

And I played the records you mentioned. Thought about song structure, like you said. Because it’s structure that counts. Isn’t it?

Oh yes. Always. Can’t be left to chance. Can it?

No, she said. You’ve got to interpose.

Yeah, show your intelligence.

Always. That’s right. Always show your intelligence.

A girl with long blonde hair pushed past. She wasn’t Lulu. Then a plump, moon-faced Korean. He wasn’t Lulu.

Look, breathed Sophia. I have a friend up here. Maybe we could go to her room.

I’d been looking around, I think. There seemed to be hundreds of people who weren’t Lulu. In a hubbub of voices. There was a coat draped over a chair. A bag encrusted with badges. Maybe students still wore badges.

And yes, I recalled the badges we had worn. Badges about the miners’ strike. Badges to save the rainforests.

But maybe I hadn’t been listening.

Pardon? I said.

Room 48. Second floor, Flinders. We could go there.

Three chocolate biscuits, I thought. And a pink wafer. No one ever liked the pink wafer. No, no one liked the pink wafer. Did they? Did anyone like the pink wafer? But the chocolate was melting.

We could go there? I repeated.

If you want. If you’d like.

If I’d like? Room…

Forty-eight. Second floor on Flinders. I could try out my new song. That’s where my guitar is. Been working for ages on it. You heard a version that time in the shop. I’d called it ‘Southern Rain’.Well, excuse me, but it’s really changed since then… It’s unrecognisable. Different key. And the tempo’s much slower. The words mean so much more now. I just feel more experienced. A different person.

Yeah. You look…

Older, you said. I take that as a compliment.

Different key?

C. That’s C major. But I don’t want it to be too mournful. It’s got to…move.You know?

Move?

All music moves. Doesn’t it?

But, to room 48?

Yes. We could go. There.

Great, I said. I’d like that. I’d love that. Flinders?

Forty-eight. Second floor. Up the stairs. Look, I’ll see you there.

Course, I said. I’m coming. Now. But what did you say that song is…

Is called now? ‘Southern Rain’.Oh yeah, it’s still ‘Southern Rain’. I won’t change that for anything.

And was it called ‘Southern Rain’when I heard it first? I asked.

Yes. It’s always been ‘Southern Rain’.Always will be ‘Southern Rain’.

And she hummed it. Hummed a song called ‘Southern Rain’.

I tried to remember where I’d heard the song before. I was sure I’d heard it. But there are so many songs these days. Thousands of downloads, millions if you thought. Who needs? I wondered, who needs…?

The Spotify songs. All the box sets. Like cutlery, I thought. The spoons you’ve never used. Polishing the spoons you’ll never need. Your reflection in every spoon. Your face stretched in a silver spoon. All the medicine you’ve taken. The medicine…

See you, she said. In a bit.

See you, I said. Her hair was different now. Fairer, almost blonde… It was…

She turned and was about to leave.

Hey, I said, as she was disappearing. Let’s have a drink. Is it? At the bar? It’s crowded in here. Don’t you think? The Central’s bound to be quieter.

Sophia seemed surprised.

Scores of new people were now coming past. The lovers, the lonely. All with songs in their heads.

Then Sophia smiled.

Yes, it’s the lunchtime rush. Getting worse. You know, she whispered. I hardly know any of these people.

Nor me, I said. Maybe I taught some of them. Last year. Or the year before that.

There was a corner of the Central Bar where I put down our drinks. We’d both decided on glasses of sauvignon blanc.

Must be strange, said Sophia. To be a teacher, I mean. Every year, your classes the same age. The girls, the boys. But you, another year older. Must be strange.

Oh yes, I agreed. It’s … peculiar. If you think about it. So maybe a teacher shouldn’t think about it. But then, you reach a particular age and perhaps it’s better…

Yeah?

Not to think about anything at all.

Because? Oh, well. Obviously…

Yeah. Obviously.

But how long? asked Sophia. Have you been a teacher?

Thirty years. Started late. But thirty’s enough.

I suppose so. But then, I’m a writer. I’ll be a writer forever.

Maybe I looked at her then. Maybe at our yellow wine.

Will you? Really?

Oh yes. Look at Leonard Cohen. Still doing it. A cousin of mine saw him in Sydney.

Yeah, great, I said. Maybe I should try the miserable old bastard again. Give him another chance.

You’re not a writer? Are you?

No.

Well then…

Well what?

Maybe you don’t understand…

Maybe I took a long pull.

Christ, Soph. I understand all right. When I was your age my friends couldn’t imagine a group still playing gigs at thirty.Thirty?we thought. Thirty’s ridiculous. But what if you’re fifty, sixty. Seventy-bloody-five? Do you stop?

Leonard’s seventy-bloody-eight, breathed Sophia triumph-antly.

But do you stop?

No. Like, what for? Because…

Soon enough you’re dead?

Well … yeah.

Then good on Leonard Cohen. I’m having another.

Not for me, please.

Go on.

I hardly ever drink.

Got to start. If you’re a writer you do.

That’s a myth. Don’t typecast me. Look, just because I’m a writer you can’t turn me into a cliché.

Hey, relax. White wine’s nothing terrible. I’m sure I’m always better with a drink inside me. Most people are.

Well … okay, she smiled. But I know I’ll always want to write. Now I’ve … discovered writing. Now I’ve felt how good it is. How real it is.

It’s like you can’t remember what you used to do before?

That’s it. Spot on.

See. I get it.

It’s like, there was all this time and I just wasted it. But now I understand what I was born for. Born to do.

And no one’s going to argue with that.

But I bet you do, she said, turning up her face. Write that is. I bet you do.

Perhaps I allowed the question to float. I came back with the sauvignon in an ice bucket. Then two new glasses and a bowl of pistachios.

Cheers.

Cheers, she said. Sipping her first glass for the first time.

Course I do, I said. Of course I write.

Then I corrected myself. Or maybe what I write down are ideas. Ideas for writing. No, not the words themselves. Not the actual words.

We both looked round, then.

I suppose I make lists, I said. That’s writing. Isn’t it?

Oh … yes. I suppose.

Yeah, I compile. I’m a brilliant compiler, me.

And what do you compile?

The soundtrack.

Sophia raised an eyebrow.

Yes, I compile the soundtrack to our lives. Okay, my life. Not yours. But mine. And a pretty good soundtrack it is too.

Essential task, she smiled.

So, should I say, of course I want to write. But first of all, I read. Which is an art. An occupation we’re in danger of losing.

Why don’t you paint? You teach art. After all.

I was always … about to start. Always on the brink. Waiting for the moment it felt right.

It always feels right for me. Now.

Hold on to that feeling. And practise that guitar!

Every day.

You could play here, I told her. At the Central. There’s a stage at the far end. But it might be possible down in this corner…

Don’t worry. I’ve checked it out already. We were here last night. It seems Thursdays are unplugged nights. You put your name down and wait for the call. So Thursday it’s going to be. And that’s tomorrow. Oh, Richard!

Thursday? Wonderful. Soon you’ll be quite the troubadour.

Trobawhat?

Don’t tell me…? You know … a travelling minstrel type. There’s a club in London. Called The Troubadour.

But … I’m not … very good.

Was Leonard bloody Cohen very good? He had to start somewhere.

I just strum in C.

One chord? If I knew one chord you couldn’t keep me off that stage. One chord’s all you need.

Actually … I’ll be over there. Sophia gestured to the corner where she’d perform.

But one chord? That’s all it takes. Confidence is your only ingredient. Promise me you’ll do it.

Another guitarist would help. Maybe bass. Fill out the terrible silence. But yes, I’ll do it. Of course I will.

So do it.

Yes, she said. I have to. You’ve just got to … push yourself forward. Haven’t you?

Tomorrow evening? I said. I’m staying at The Sebel. Maybe I’ll come over. Hear how you fill that terrible silence. Hey, I’ve thought of your first album title. What about Troubles of a Troubadour? What about…?

THURSDAY

5am.

Darkness.

A raindrop on the tip of my tongue.

I thought of the Caib Caves. The cold of the walls. The roofs of rock. Where even the quartz is grey. Where it’s always raining. That limestone rain.

Out at the bus and tram stops. That group of natives was being moved away. One of their children was crying. It’s police policy, someone said. Two, three days, then move ’em on. Standard practice. Don’t let them get comfortable. Don’t let…

It’s not easy to see the photograph in first light. Still, people seemed to think about it. I might have appeared desperate. Or needy. So they looked.

Maybe that’s how I must be to everybody. Because I haven’t shaved all week. Haven’t thought about it. There are more important things to do than shave.

You see, I don’t want to pretend anything now. Yes, I’ve finished pretending. Maybe that’s the last part of growing up. When you realise you can stop pretending. The relief of not pretending. The terror of it.

Because you realise that’s what life can be. Pretending. If you allow it. You realise that’s how you’re spending every minute. Maybe even your last minute. Pretending.

But pretending what? Pretending you haven’t pissed yourself. Pretending you care. Pretending you don’t care. Pretending you know what you’re talking about. Pretending you know what everybody else is talking about.

Pretending you don’t care that the barman hasn’t cleaned this table. I care about that. Does that make me alive? Because, look, there’s wine spilled in the middle of the table. Or icewater. My glass is leaving rings in last night’s spills.

When I showed the photograph to a man at the bar he shook his head. Shook his head. But was he pretending not to know? Or pretending not to care?

Yes, the barman’s coming round now. Excuse me, boss, he says, excuse me. I lift my glass and allow him to do his job and I can still see the wet rings my glass leaves and maybe I should be doing this in my room, this thinking, this searching my thoughts, but I don’t want to be alone, don’t want to drink that way, because The Brecknock is where I brought Lulu once and she seemed to like it.

When he wipes the table I show the photo again. He says already seen it, sport. And the answer’s the same.

But no, I think. It’s a different world now. So the answer cannot be the same. In a different world the answer can never be the same.

I think Lulu and I sat in the same seats that afternoon. Under the mirror. Lulu ordered wedges. Yes with spicy mayo. There are so many places we sat together. Toasting our lives.So long, Arcturus. So long.

A notice on the wall tells me there have been only three landlords at The Brecknock in one hundred and fifty years.

The man who wiped my table might be twenty-five. He’s a strong-looking kid but tiredness has entered his eyes. His eyelids are mauve. He has a small-hours pallor.

Take it easy, I want to say to that boy. Son, rest your head. Upon the bar. Try and remember your dreams. Because this is the country of the Dreaming.

When he cleans my table he uses an old tee shirt with a yellow smiley face design. And look, here he comes again. He’s here again.

Instead of sleeping he’s working. Instead of placing his cheek against the cold metal of the counter, he comes back.

I think he asks can I get you another. And I am surprised. Yes, I am disconcerted.

Yes, thank you, I say. Another would be good.

And I think I mean what I say. I think that’s what he said.

And no, I wasn’t pretending. About that. Because that’s another challenge, isn’t it? To understand you’re pretending you’re not pretending. Or is it the other way around?

And what? I say. What’s that?

Yes it would be better for you, he says. Better for you. If you did. Yes better for you…

If I what?

Better for you. Better all round.

Better for…

If I?

If you

Better all round.

If I…?

Shove off.

But it’s a girl now. A girl behind the aluminium rail of the counter. This new girl at the bar I haven’t seen before. She lights a candle and the glow runs through the room. Like a fuse.

No, she says, no, I haven’t seen her. You’ve asked everyone, sir. No one has seen the girl in the photograph. And sir, sir.

Someone is pointing out there’s blood on my cheek. That blood is dripping from my nose. It’s happening again, I don’t know why. It happened this week. Or maybe last month.

Maybe that man hit me. Maybe that man on the high stool at the bar. He was there a moment ago. I didn’t like the look of him. No, not at all. But I showed him the photograph, asked him to remember.

But it’s a woman on the stool now. A woman with long legs. With black, with black. Stockings. Yes her legs so long. Stretched out before her. A woman taller than me. Yes she’s taller. But how tall is she really? I wonder, how tall is the woman at the bar?

Now someone is wiping my cheek. There’s blood on the cloth. Blood on that tee shirt with the yellow smiley face. Yes maybe he hit me. And maybe he didn’t. Or maybe the woman with long…

But the blood’s running over my fingers and I think, in that one hundred and fifty years in all that time you’d suppose you’d suppose on the streets of Adelaide for one hundred and fifty years I’ve been searching the violet light creeping up the glass the southern rain starting to speckle the glass and the signs in a language no one understands.

Everyone is pretending. Everyone today, tonight in The Brecknock. So here we are.

Pretending I haven’t pissed myself.

Pretending they’ve not seen Lulu.

And salty, I think. My blood warm. And so salty.

Like rain on The Caib. That rain’s cold, but it’s colder in the caves.

Yes, I’ve stood listening. To that dripping. That dripping that goes on forever. I’ve waited for it to stop and realised that it’s music that will last for. Ever.

Stood there shivering. Felt my whole body. Shiver. Yes looked around and seen the ages of starlight grow dim in the stone. Seen the corals white and dead locked into the stone. And I’ve run away. Over the pebbles and through the pools. Run away as quickly as I could.

FRIDAY

Woke and slept. Woke and realised something was wrong.

Bleeding again. The bright noseblood everywhere. When I found the light I was afraid.

There was so much. A red pond in the dint my head had left. A wet stain on the cream Sebel Hotel pillowcase. The Sebel monogram in the corner.

My first reaction was to hide it. Yes, hide the evidence. Of bleeding. Of whatever’s wrong. But Thursday was my last night here. When I go down to reception this morning I will pay the bill and walk out and then and then…

I put on all the lights and fill the bath with everything the hotel’s provided. The soap, the shampoos, the conditioners, the body lotions in their plastic sachets.

And I don’t even look. Simply pour it all into the water. Roaring into my 5am bath.

And I soak. Up to my eyebrows. Then immerse myself until I splutter up from the hot water. Then down again. Then up. Then down. Again.

I think of The Chasm. My face between Lizzy’s legs. My blood on her thighs and Lizzy’s seawater taste mixing with the taste of my blood.

That afternoon, all of us ready. The sun shining into the caves. No trace of a shadow on the neolithic blue of The Caib. All of us ready. For the rest of our … the rest of…

At reception I look at how my bill has been calculated.

No, I say. You’re confusing me with…

The girl tries to specify each item. Then has to wait for an older woman to come. Then wait for the man who had smiled at me on Monday. Ages ago. Eons…

I paid for the malbec at the bar, I say. On Monday. Paid with cash.

But the Tuesday malbec, sir?

Tuesday?

Also on Tuesday sir, the peanuts? The crisps? Please look at the details, sir. Then the malbec on the Wednesday, sir? Both miniatures of the scotch on Wednesday, sir. Wednesday supper brought to your room. Both miniatures again, sir. You ordered the minibar replenished every day. I spoke to you myself on Thursday, sir. That was yesterday.

Replenished? I asked. What a word that is. A terrible word. A word from a different world.

I was trying to make a joke of it, I said.

A joke, sir. Yes, I understand, sir. And the telephone account is such as it is because you regularly called the same number.

Goolwa, I say. I rang a shop. Goolwa’s sixty miles away. Sweet sixty.

I know, sir. You often called at night, sir. Or very early in the morning.

Just checking, I said. I had to check up. But it was always answerphone. Except the day that…

Some of these calls were made at unusual hours, sir. And you must have left long messages on the answerphone, sir. Do you remember, sir? One of these calls lasted ninety-three minutes.

Ninety-three…?

Ninety-three minutes and fifty-seven seconds. A call made at 2.30 in the morning.

It’s a big responsibility, I tell him. When I’m away.

And this call? It’s longer. One hundred and twenty-seven minutes.

One hundred…?

Of course, sir, I can itemise the charges for you once again. If it will help. Of course, we already have your credit card details.

And the man smiles at me. For the last time, I am sure. There he stands, dark shoulders, no dandruff. Perfect Windsor knot. Today he is wearing a name badge. Perhaps he had worn it on Monday.

Stephen Wright,it says.

Woah! I say. Woah!

Pardon, sir?

Hold up, Stevie! I say. Hold up, Little Stevie Wright. Woah, boy.

Pardon, sir?

Stephen Wright, I repeat. Wow, it’s Stevie Wright.

And the man does smile again. A face I expected to be full of loathing lights with long-suffering good humour.

My parents were fans, sir. I live with it.

And do you sing, Stephen? I ask.

Regrettably not, sir. My mother was the driving force. More so than my father. In fact she attended Stevie Wright’s, what shall we say, his comeback concert. The Legends of Rock, sir. Held up in Byron Bay? Oh yes, sir, I know all about Little Stevie Wright.

Hard to credit, I say. That he’s still alive. After everything he’s been through. And, did you, did you ever…

Sing, sir? Lots of people have asked me, though less often now of course. But no, never, I never sang. I used to be asked all the time, sir, but I never wanted it. My career took a different direction.

And I look at Stephen Wright behind The Sebel Hotel’s polished counter. Stephen Wright with his fat silver tie. His brushed shoulders.

Well, Stephen, I say, ‘It’s gonna happen… It’s gonna happen…

…In the city,sir? WhereI’ll be with my girl, sir? She’s so pretty,sir.

Yes, perhaps it’s going to happen, sir, You see, I used to listen to that song, when I was much younger. In fact, I bought a copy. The first record I ever bought.

She looks fine tonight,I say.

And she is out of sight,returns Stephen Wright.To me.

It’s gonna happen,I say.It’s gonna happen,it’s gonna happen…

In the city,sir? Oh yes, sir. Where everything happens. After all. Please sign here and thank you for staying at The Sebel.

I collect my car and drive through the Adelaide traffic down the peninsula. I wait above some of the beaches we’d visited. Everything is a dream.

In Victor Harbour it is easy to park. Then I hop on to the horse tram setting out for Granite Island. There are only two other passengers.

Yes, I ask them whether they’d seen Lulu. And they quiz one another. Taking it seriously.

Have we, Daddy? Have we?

I think so, says the man.

I think so, says the woman.

Oh boy. They are doing their best.

Such a sweet-looking child, the woman says. Is she your… I mean, is she your…?

No. No, she’s not.

Eventually, they decided. No, they hadn’t. No, they were sure.

The woman put the photograph back into my hand. Her mouth tight.

Thank you, I say. And wander off uphill.

But how might anyone be sure? Even I who had looked one hundred times at that photograph, could now remember none of the details. Could recall nothing.

Lulu is vanishing. A mirage above the Murray. A wisp from the ashen hills.

There are penguins on the island. They make the island famous. Everything is done to preserve those penguins.

You know, I say to a man on the granite track. They don’t deserve it, do they? They bloody don’t deserve it.

Who doesn’t deserve what? he asks.

All this, I gestured. The whole island. Those stupid bloody…

But he shrugs and pushes on. So I am able to have the bald rock of the granite headland to myself.

Penguins.

At the lookout, I am alone. I think a few people pass. Then I head down to the restaurant at the bottom. Where I sit and stare. Contemplating the ocean.

That sea is like old silver paper. Crushed and crinkled. Like the silver paper I used day after day at The Works. Its silver darkening, getting dirtier…

I remember my mother with tins of Silvo. That filthy stuff. Just a gritty paste. But she’d rub it in and gradually all the tarnishing of anything silver, her best cutlery, a few vases, would vanish.

A miracle, for a while. I used to watch her polishing. And wondered why she bothered. Why she would make that effort. Now I understand.

It was the same silver as the beach when the tide was going out. The same silver as the smoke that poured out of The Works. I used to walk west and see that silver beach spread out. The mosques and minarets of industry. All silvered in the dawn.

And I thought, up on the Granite Island lookout, there’s nothing now. No, nothing between me and the icefields. Nothing between me and Mount Erebus, that volcano at the start, at the end of the world. Nothing between me and Wilkes Land, that desert at the start, at the end of the world.

No, there’s nothing. And I asked myself, how did I get here? To Granite Island? With all these, all these …penguins.

Yeah. How did I…? How…

And I thought, no, not how? Why? Why is the question.

I looked at the sea. There were cloud shadows on the waves. As if the water was deeper there. As if the sea was tarnishing. That water was a different colour, like ice I’d see in rain barrels on the allotment. Silver skins around black embryos, that ice.

Yes, that ice was like drowned babies. It’s what I always thought. Cycling down Amazon Street, going past The Lily, then The Cat, going through The Ghetto and under The Ziggurat, that’s what I thought.

Because I saw one once. Or thought I saw. A drowned baby in our rain barrel.

Can’t remember if it was a joke Dad made. Or something my mother said. Or maybe a dead cat, or a bat.

Yes, I found a drowned bat once in the rain butt. And that’s when the idea came to me. From then on I always looked specially.

And I came to expect it. But then, when there was no drowned baby, I’d be, I’d be …disappointed.How strange is that?

So, I used to push the ice down. Into the barrel. Or sometimes I broke that ice, sometimes smashed it to splinters, scarring it white. And I scratched my name on that ice a few times. Yes, RIP, scratched it with a pen or an old fork we kept in the toolbox. The only writing I’ve ever managed.

Then I would look into the water of the rain barrel. Water too cold to touch. Too cold to bear. Water as cold as the seawater around Granite Island.

There were hundreds of miles of water until the next land. And the next land was the dead land where no one had ever lived. Only marooned sailors, or fur trappers who might have survived mutiny or shipwreck.

Because there are more islands than you’d think off that coast. Islands all the way to Antarctica. I used to know their names. Islands like splinters of ice.

You see, that’s how I passed my interview for Adelaide. By my diligence. I prepared for days. No, for weeks. Yes, I even researched those barren islands. Where no one has ever existed and never will live.

Imagine that, no history, no culture. Nothing to inherit. Only thousands of years of birdshit whitening the cliffs. And bird song. That insane racket no one will ever hear.

But I fooled them, didn’t I? Those worthies on the interview panel. Yes, they told me they would be taking a risk. Told me on the video link. Told me it was a very long way, a very long way from…Where is it you come from, Mr Parry? How close is that to…? How far from…?

I tell you, that interview is the most coherent I’ve ever been. I knew when it was over I had the job. I couldn’t imagine not getting that job. No snuffling, no coughing. No bloody stammering.

All those speech therapy lessons worked out. Didn’t they? Richard Ieuan Parry, stone cold cert.

Yes, all that speaking with a limestone pebble in my mouth. Thank you, limestone. I remember how you tasted. Yes, the salt of you. The dangerous limestone taste of the sea.

I could swallow this, I always thought. Break my teeth on this pebble. And ruin my smile, ha ha.

But don’t tell me they didn’t get their money’s worth. I slaved for that school. Early mornings, late evenings, weekends. And thenHey Bulldog, as if school wasn’t enough. On top of it all I ran the Bulldog.

When I put my hands in the water in the barrel I would hold them there. As long as it was bearable. Then I’d examine my skin. The white, the mottled, the purple skin.

And I’d think, this must be what it’s like when you’re dead.

I sat on that lookout rock until I realised I was aching. The lights were on in Vincent Harbour by then. The horse ferry long gone. I had to walk back along the causeway.

Before that I returned to the restaurant. It was deserted. But I stepped over the chain and sat at the table Lulu and I had first chosen.

That afternoon I had ordered a bottle of sauvignon. Yes, like they say, it reminded me of gooseberries.

That’s the cliché, isn’t it? And that’s what I told my best kids. Between twelve and twenty, it didn’t matter.

Don’t use clichés, I’d say. Try and discover what no one else has ever said.

You know, all my classes ended with ‘P’. Started out with 12P. Moved on to older kids. By the end it was 17P. Bigger than me, the boys in 17P. And in 16P they were bigger too. And 15P.

And don’t mention the girls. Just don’t…

But every year, they’d call me the same name. Ripper. Sometimes Jack, but generally Ripper. Or Mr Parry to be formal.

Talking of 16P, who became 17Z by the way, under the care of Mrs Zacharias, I once told them about the corals of The Caib.

You what, sir? they all asked. Show us on the map where you come from. Show us again.

So I’d point out The Caib and they’d laugh and ask if I’d ever been to the Great Barrier Reef. That’s where the coral is, Ripper, they said. The GBR.

Caib coral is fossilised, I’d say. It’s the ghosts of corals that lived millions of years ago. Some of it’s white or bleached. Generally, it’s no colour at all.

Ghost coral sounds dead, sir, the clever ones would say.

But there are real corals, still corals around where…

And I’d lose them in the reaction. As I was howled down.

Seems I wasn’t allowed to trespass on Aussie territory. All I was doing was telling them about what I’d dig up in the sand at home. Coral the colour of pearls of arsenic. Coral like droplets of fog.

So much we used to uncover. In the limestone earth. Thousands of pieces of china, most with a pattern of blue flowers. Unrecognisable bits of iron. Old iron.

I never said to those kids they might find nothing in Adelaide. Course I didn’t. But so little of the land had been settled. Not that it would have been an insult. Not at all. But you know what I mean.

You see, I was going to make an installation of everything I’d dug up. I thought of it years before I met Libby.

I kept all those bits in glass jars. The corals, the pottery. Kept them ready. I wanted to exhibit my own archaeology.