9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

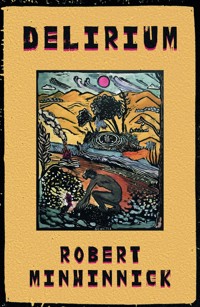

"…small, beautiful gem-like fragments adding up to a satisfying, lapidary whole." Jon Gower: Nation Cymru "Minhinnick makes the case for [delirium] in busy, fragmented prose, which is polyphonic in voice, time-bending in span, and a whirlwind to read." Wales Arts Review. In Delirium Robert Minhinnick addresses his square mile: a small coastal town and massive sand dunes. But its uniqueness is challenged by the algorithms of globalisation, by the climate emergency, by a changing world led by corrupt, inept politicians. This thought-provoking book celebrates the ordinary and everyday, our vital bedrock for life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 125

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

DELIRIUM

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd.

Suite 6, 4 Derwen Road, Bridgend, Wales, CF31 1LH

www.serenbooks.com

facebook.com/SerenBooks

twitter@SerenBooks

The right of Robert Minhinnick to be identified as

the author of this work has been asserted in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

© Robert Minhinnick, 2022

ISBN: 9781781726723

Ebook: 9781781726730

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without

the prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Books Council of Wales.

Cover: original artwork by Dan Llywelyn Hall

Printed in Bembo by Severn, Gloucester.

CONTENTS

Decima & Albert

The Magic Shop

Feeding Porridge to my Mother

A History of Sunburn

Gate of India

Plovers, February 28

Cynghanedd

The Extinction Circus

The Extinction Circus

Rewilding

Emily: An Algorithm

Gorwelion

Thanks for Riding

The Lapwing

The Fairy Buoy

from Billionaires’ Shortbread

Ffrez: Fever

Cai: The Yellowhammer

Ffrez & Taran: The Satyr

Cai: Razors

Taran: The Palestinian

Ffrez: Marooned

In Tom Briton’s Country

On the Set of Lawrence of Arabia in Tom Briton’s Country

Alleged Autobiography of a Sowerby’s Beak-Nosed Whale

Red Magpies at Bwlch y Cariad

The Riders at Pwll y Tom Briton

Burning the Sunflowers

Lizards

Golden Plover at Ffynnon Wen

Snipe, Vanishing

Schwyll: The Great Spring of Glamorgan

Fellow Travellers

Fellow Travellers

DU: Screenshots

Decima & Albert

The Magic Shop

I’m talking to Deci again. My turn forever now, making up stories, as she always told us stories when we went home for dinner.

“Remember HG Wells? Of course you do.

I chose the collected works, a set in red boards, one whole shelf from Albert’s parents, but I always come back to the short stories. My latest favourite is ‘The Magic Shop’. Just listen to this:

I had seen the Magic Shop from afar several times; I had passed it once or twice, a shop window of alluring little objects, magic balls, magic hens, wonderful cones, ventriloquist dolls, the material of the basket trick, packs of cards that LOOKED all right, and all that sort of thing, but never had I thought of going in until one day…

I think you’ll love it and one day I’ll read it all for you. Maybe it’s because of what I do now, opening our little shop on winter mornings. Its porch is where people shelter. Sometimes I have to clear up their vomit. And once it was human shit, not dog’s.

People congregate in the bandstand. Gradually you learn some don’t have homes. I know, I know…And sometimes when I unlock the door I swear I can smell cordite. Fanciful, you’d think? A whiff of battle come to our shop?

But there are six wooden chests there and branded on each, the words ‘collate for destruction’. Each is zinc-lined and all stored howitzer cartridges on HMS Victorious in World War One, for which vessel, Robert Scott was flag captain. These six chests have the letters AE BROOMFIELD burned into the lids, and the codings branded, secured by brass hasps.

And now, one hundred years later, we use them to store cushions and silks and dresses with tiny mirrors sewn into the fabric… those hasps fat as Babylonian dates, redgold and rusty under the palms, that palm grove beside the Euphrates where I paused and wondered, the dead fronds crackling under my feet, wandering the temple rooms where goats had shat their black pellets, goatbells the only music that was left in Babylon until the tanks arrived, and the soldiers discovered the demons that lined Procession Street…”

Feeding Porridge to my Mother and telling her about the Deer

The agency nurse takes me to the agency chef. I explain that you’re hungry, and it’s the first time you have ever asked for more.

It’s hot, I say, when I carry back the bowl to Room 19. Straight out of the saucepan. And I watch you blow on the first spoonful, but it’s scalding, and I stir the bowl and stir the bowl until you can try again. And try again.

Half an hour later the porridge is gone. A whole panful with extra sugar and milk, and I realise I’ve spent thirty minutes telling you about the deer. Yesterday morning, I say. In driftwood light.

Suddenly, they were there, ghosting amongst the blackthorn, those trees themselves ghostlike at that hour. Maybe three. Maybe four roe deer.

Skulking?

Do you love that word? I do.

But no. In hiding. As ever, in hiding. Impenetrable I thought, that blackthorn wood, each tree a ghost, its thorns out of the sand, those thorns being spells and splinters, spills and spikes, and one still hot in my heel.

The does were chewing the blackthorn bark and were not expecting me, another ghost, but downwind, on the first morning in May. Three of them, and when they turned together those deer were spotted like vipers, or striped, I suppose, in perfect camouflage.

Yes, hidden, the deer. Out of hiding then vanishing into the blackthorn’s dirty ivory, yellowed in this latest hurricane they’re calling Storm Hannah.

Yes, deer, I say. Think of that. We don’t often see deer in the dunes. And, of course I’ll go again, but I don’t believe the deer will still be there…

A History of Sunburn

Sometimes the visitor comes through the wall and sometimes the visitor is an animal and sometimes the visitor is someone she has seen or remembers from a past no-one else can share and sometimes the visitor has the wrong name and sometimes there is no-one there when she says the visitor has arrived and sometimes I look into her eyes and wonder who is this looking back at me…

*

UV levels increase in the spring across the UK, reaching a peak in late June.

In this current spell of fine weather, we could see some of the highest UV levels ever recorded.

“Normally they’re about six or seven in the summer months,” says BBC Weather’s Matt Taylor. “Today we could hit a nine in some parts of southern England and South Wales.”

BBC News for June 25, 2020

…while 75 years later I’m walking the lanes to Picton Court to verify how you are, recalling that you said Albert always kept a mouthful in his canteen, while the other soldiers finished every drop…

First thing I note is three of your friends out on the grass in straw hats, the nurses wearing orange masks. Not long ago, I could have told what villages those nurses come from.

But you’re in bed and I’m talking through the double glazing and you’re not hearing. We’re all thinking of you, I say finally. Shouting love. Miming love.

Turning away.

Perhaps you hear me but I go back, past the horses we’re told not to touch, and avoiding a woman coming in the opposite direction in her own mask.

Ah, sweet embraceable you! I want to say.

Am I the monster from your imagination, unmasked and anonymous, looming out of the honeysuckle?

Behind me stands Cefn Bryn on Gower.

I’ve always thought it my personal volcano,

its long eruption burying us in invisible ash.

They’ve cut the wheat, its stubble almost white, and sharp as limestone. My watch has stopped but this could be any hour in the last ten thousand years, and my mother is looking at the screen because Matt Taylor is speaking again, all about UV.

So I think of Albert in his own June, watching the cobra moving past the cookhouse, writing how ten weeks after VE Day

the Japs attacked last night.

and one week later the Welch suffered very heavy casualties …

And on August 8, Atomic bomb is used on Japan…

a ghastly weapon this but should end the war quickly…

Then on Wednesday, August 14, he writes

peace in the world

but one of the horses is wearing a fly-sheet to save it from sunburn, and soon my lips are crusted and my tongue flickering in the air like a snake.

Yet I keep thinking of Albert, twenty,

with mules and wireless, guarding his water ration,

and writing a diary for people he never thought about.

And I suppose that’s exactly what history is,

like my last sight of you, behind the glass,

raising your hand and mouthing words

impossible to hear…

*

Sun-burned, we come up from the orchid field, one thousand I’d say, no, make that two, surely, two thousand, that forest of coral spikes in the bleached grass.

And then as I am looking down, it appears exactly as I imagine it should.

At it always must. But my daydream is no delirium.

So there is no mirage, yet maybe an apparition.

But what I see is what I see, a creature erupting

out of the hot and hollow earth.

And yes, I have a witness for this. I can call on her shared vision.

Some might say dune tiger or rubies in the sand, old-fashioned gemstones a child would scatter from the jewellery box, a grandmother’s cairngorms perhaps.

Or even a cudgel of sorts, perhaps an amulet, but for me this is my coldblooded familiar, basking in its coils under the hemlock.

Yes, this is the basilisk, midday midsummer, mute, no malice, yet I skirt the serpent where it lies, deaf but squirming away, caustic, shrewd, from the echo of myself, the blood in my boots, the heart in my boots, the earthquakes it senses in every step, lidless, lethal, condemned to stare forever at disbelievers such as I, but both of us refugees from an eternal blood feud.

On June 12, 1945, Albert Minhinnick had written in his diary:

This is one of the worst

malaria areas in the world.

Also cholera. What a dump….

This time I drive. And I am able to enter Room 17…

Yes. Me again. You know that shop where I work?

We’re selling masks now, a woman is sewing them from her best material.

A real seamstress, I’d say. Have to look good for the plague, don’t we?

Floral pattern all right? So try to put it on and maybe it will be a soldier who tests you. He or she will also be wearing a mask. But don’t worry.

They will be as frightened as you, and as young as you once were, hearing the German bombs falling on Wind Street, Green Dragon Lane up to the Adam and Eve, and that one much nearer, close as the hayrick in Ty Mawr next door.

You were hiding, you always said, under the dinner table.

But who could believe the army rolling up the driveway into Picton Court?

They’re testing for those golden stars on your screen that all the children are painting, gold and red and green that strange constellation suddenly visible in Room 17 and all around the world…

Gate of India

(Based on the 1945 diary of Private, then Corporal Albert Minhinnick)

Vipera

Twenty, wasn’t he?

And in his diary for Tuesday, May 8, he wrote:

Heard peace has been declared in Europe.

Celebrations in evening. Bonfire and beer.

Had some fun.

Day off.

On Tuesday, July 2, he saw a five foot cobra killed with rifles and revolver. Full of snakes, he found the forest. If he cut one open there’d be another snake inside. A snake might swallow an even bigger snake. I know he thought about that, lighting up.

What was the worst one, then?

He considered a while.

Kraits, he said. The kraits were bad.

We’d been talking about how the other side hung microphones in the trees and taunted our side, also scorpions and the little tribal women who sold eggs and charged a packet of ten cigarettes for each egg. They were headhunters.

But my question was what any son would ask his father.

Did you ever kill anyone?

He looked at me and smiled.

Yes.

Yes?

Yes.

Yes!

He smiled again. And moved away.

Twenty, wasn’t he? Now, I don’t believe his answer.

I don’t think he killed anybody. It doesn’t fit with the man I knew, who kept a mouthful of water unswallowed when others were cursing thirst.

And dying of it.

But bullet or bayonet? Maybe he’d thrown a grenade?

Caught and tossed it back like a cricket ball.

They did that in films.

He left university knowing there were stories to write. Yet maybe he had. Killed someone.

A soldier on their side?

Because he never boasted or wore his medals, though hating their emperor, despising their jobs. But he was mysterious, this man.

Perhaps he had pulled the trigger on a lucky shot. Or bayonet practice saved his life. That man, emaciated in his demob suit, still to meet my mother.

Yes, dead skinny, bored with signal exchange, waiting for the parcel of cigs, and regarding the cobra by the cookhouse door. And now quick as his arm unfisted, two foot six, that arm unblued and unblemished from Mawchi to Mumbai, commando in the forgotten Fourteenth, no hate no love across knuckles or his clerk’s fingers, radio man of whose autobiography in morse I could never get the hang.... But two foot six my own snake attuned to the reverb in my boots come out of the sand, golden my serpent with diamonds burnt diagonal on its back and delirium in each hollow fang, but moving as the knight moves on a chessboard – in slick dislocations.

And later he built walls around our house, hawks and floats his story then but never a mason’s line with that mineral arithmetic and no blue chronicle or needleworker’s lexicon his skin to prick, so maybe that was the clue to what made the corporal tick...

The Days after Hiroshima

January 22nd he wore tropical clothing the first time.

Then Sunday saw flying fish, Monday porpoises.

How much did he want to know? And what might he never tell? The answers could be somewhere in this tiny leather book bought in Motherwell.

But amongst the shitehawks on the ramparts at Rangoon he drank char in bucketfuls, wrote nothing much changes here and there has been nothing very startling to record.

In real ink, in pencil, the days after Hiroshima were days waiting for the parcel of Senior Service.

Oh, his parents had bought a new house. Incredibly life was going on without him. It’s like what some of us call Face Book, old man.

He noted Thomas and Bond were in hospital with malaria, and whether from Cathedral Close or pisspoor Ysgwyddgwyn most of the boys also found they copped a dose of fevers and dreams, fevers and dreams.