28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

The Lotus Elan was Lotus's definitive roadster. It replaced the elegant but expensive Lotus Elite and was the first car to employ the innovative Lotus steel backbone chassis. The original Elan was produced as a two-seat, open-top sportscar and hardtop coupe from 1962 to 1973. The range was extended by the addition of the 2+2-seater Plus 2 from 1967 to 1974. Lotus introduced an all-new front wheel drive Elan in 1989, the M100, which was produced until 1995. Lotus Elan studies the history and development of all the Elans and describes each model in detail. It gives technical details for all models, examines unusual conversions, and includes driving experiences from Elan owners. A complete and readable resource for all Lotus Elan owners and motoring enthusiasts who aspire to own one of these iconic British sports cars. Superbly illustrated with 250 colour photographs.Matthew Vale is a motoring author and passionate Lotus Elan enthusiast.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

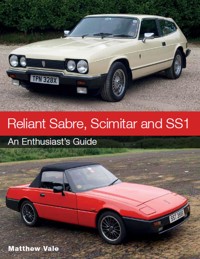

The Complete Story

OTHER TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

AC COBRA Brian Laban

ALFA ROMEO 916 GTV AND SPIDER Robert Foskett

ALFA ROMEO SPIDER John Tipler

ASTON MARTIN DB4, DB5 & DB6 Jonathan Wood

ASTON MARTIN DB7 Andrew Noakes

ASTON MARTIN V8 William Presland

AUDI QUATTRO Laurence Meredith

AUSTIN HEALEY Graham Robson

BMW 3 SERIES James Taylor

BMW 5 SERIES James Taylor

CITROEN DS SERIES John Pressnell

FORD CAPRI Graham Robson

FORD ESCORT RS Graham Robson

JAGUAR E-TYPE Jonathan Wood

JAGUAR XJ-S Graham Robson

JAGUAR XK8 Graham Robson

JENSEN INTERCEPTOR John Tipler

JOWETT JAVELIN AND JUPITER Geoff McAuley & Edmund Nankivell

LAMBORGHINI COUNTACH Peter Dron

LANCIA INTEGRALE Peter Collins

LANCIA SPORTING COUPES Brian Long

LAND ROVER DEFENDER James Taylor

LOTUS & CATERHAM SEVEN John Tipler

LOTUS ELISE John Tipler

MGA David G. Styles

MGB Brian Laban

MGF AND TF David Knowles

MG T-SERIES Graham Robson

MASERATI ROAD CARS John Price-Williams

MERCEDES-BENZ CARS OF THE 1990S James Taylor

MERCEDES SL SERIES Andrew Noakes

MORGAN THREE-WHEELER Peter Miller

MORGAN 4-4 Michael Palmer

ROVER P5 & P5B James Taylor

SAAB 99 & 900 Lance Cole

SUBARU IMPREZA WRX AND WRX STI James Taylor

SUNBEAM ALPINE AND TIGER Graham Robson

TRIUMPH SPITFIRE & GT6 Janes Taylor

TRIUMPH TR7 David Knowles

VOLKSWAGEN TRANSPORTER Laurence Meredith

VOLKSWAGEN GOLF GTI James Richardson

VOLVO P1800 David G. Styles

The Complete Story

Matthew Vale

First published in 2013 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© Matthew Vale 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 634 5

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

CHAPTER 1 THE LOTUS ELAN IN CONTEXT

CHAPTER 2 THE HEART OF THE MATTER – THE LOTUS TWIN CAM ENGINE

CHAPTER 3 THE ORIGINAL ELAN

CHAPTER 4 THE PLUS 2

CHAPTER 5 THE ELAN 26R AND COMPETITION

CHAPTER 6 ELAN M100 – 1989 TO 1999

CHAPTER 7 OWNING, RUNNING AND MODIFYING

Resources for the Elan Owner

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, I would like to thank the owners of the various Elans featured in this book, John Humfryes, Tom Favell, Peter Shaw, Alex Black, Peter Isted and Martin Houston, for their time and cooperation and for allowing me to interview them, photograph the cars and for providing pictures of their cars.

Next, thanks are also due to Tim Wilkes (Elan Sprint) and the Club Lotus Elan Section and the members of the Lotus.Elan.net forum, as they answered several technical questions I had. Thanks also to Paul Matty Sportscars who supplied the pictures of the ‘Metier’ Plus 2 prototype. Many thanks to Christophe Faivre-Pierret and Carl Pereria for the Elanbulance pictures, to Scott Barron MD from Monroe, Louisiana, for the pictures of his emissions-equipped S4, and to Mark Kempson for the Shapecraft Elan pictures. Also, thanks are due to Andy Graham, the Lotus Archivist who was on call to answer various queries.

Finally, many thanks again to my wife, Julia, and daughter Lizzie who had to put up with me disappearing off to car shows, club meets and my study to research and write this book.

PREFACE

When Lotus produced the first Elan in the early 1960s the company was relying on this diminutive two-seat sports car to sell in enough numbers to make Lotus profitable and to support the company’s racing efforts. The Elan, with its glass-fibre body, backbone chassis and Lotus Twin Cam engine proved to have outstanding performance and road-holding and was met with acclaim from both the motoring press and owners. It was Lotus’s first truly successful road car and was produced through the 1960s and into the 1970s. It was complemented by the Plus 2 in 1967, which kept the original Elan’s format but was widened and stretched to give 2+2 seating and a more refined driving environment. The last Plus 2 was produced in 1974, when Lotus continued its drive upmarket with the Elite. The company returned to its two-seat sports car roots with the new M100 Elan, which it introduced in 1989. Lotus, then under the ownership of General Motors, only produced the front-wheel-drive Elan for a couple of years before ending production due to disappointing sales. The car was briefly revived when Bugatti took over with a limited run of 800 units in 1994 and 1995 and then the tooling was sold off to the Korean firm Kia.

This book looks at the three Elans produced by Lotus and gives a model by model description along with a technical description of the main elements of each model. A specific chapter also looks at the Lotus Ford Twin Cam engine which formed the heart of the original Elan and Plus 2. Owners’ experiences and impressions are also recounted, embracing owners of Elans both today and back in the past.

CHAPTER ONE

THE LOTUS ELAN IN CONTEXT

Introduction

Elan is an evocative name for Lotus, as it was the name given to the company’s first truly commercially successful road car. Following the sophisticated but racing-oriented Elite, the original Elan of the 1960s was the right car at the right time, a sophisticated road car based on race-winning technology, powered by Lotus’s own Ford-based engine, which gave the customer superb performance, handling and roadholding combined with acceptable levels of refinement and comfort.

The car outperformed and out-handled the British-built opposition, was much cheaper than foreign exotica and enabled Lotus to become a successful and profitable volume car manufacturer in its own right. Lotus introduced a larger four-seater Elan, the Plus 2, in 1967 to capitalize on the growing market for larger sports cars and produced it alongside the original Elan.

Lotus then moved away from the small sports-car market in the 1970s and 1980s with the larger, upmarket wedge-shaped four-seater Elite (not to be confused with original 1950s Lotus Elite), the Coupé-styled Eclat and Excel and the mid-engine Esprit ranges, which, while they were outstanding cars in the Lotus tradition, had only limited commercial success. So in the late 1980s and early 1990s Lotus tried to emulate the original Elan’s success with a new small sports car, also called the Elan. This front-wheel-drive car was aimed squarely at the small sports-car market, just as the original Elan had been, and also had class-leading performance, handling and roadholding. However, while it was critically acclaimed by the motoring press and has a strong following today, it did not sell in the numbers needed to recoup its costs and so was dropped by 1995.

The last incarnation of the Elan was the Sprint. With its excellent performance, the Elan was the epitome of the British sports car.

The Elan Plus 2 was introduced in 1967 as a larger 2+2 version of the original Elan. To some eyes it was better proportioned than the original and was an excellent GT car.

The M100 Elan was introduced in 1991 and, in true Lotus fashion, was an excellent performer.

Lotus Company History Pre-Elan

The founder of Lotus, Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman, was born on 19 May 1928, in Richmond, Surrey, and was bought up in North London by his parents, Stanley and Molly Chapman, who ran a successful catering business and the Railway Hotel in Tottenham Lane, Hornsey. In October 1945, Colin Chapman started studying for a degree in civil engineering at University College, London, from which he graduated in 1948. While he was at university he dealt in second-hand cars, but the withdrawal of the basic petrol ration in October 1947 meant that the bottom fell out of the second-hand market, and Chapman ended up having to sell his current stock at a loss, thus wiping out all his profits from the enterprise. One car could not be shifted, a 1930 Austin Seven saloon, so Chapman had to keep it. He was busily converting this into a touring car when he came across a car trial in Aldershot, and was so inspired by the spectacle that he changed direction and converted the Seven into what would become the first Lotus – a trials special.

When it was completed, the car had to be re-registered (with the registration number ‘OX 9292’) and as Chapman did not want it to be called an ‘Austin Special’ on the registration logbook, he decided to call it the Lotus Mark 1. The origins of why Chapman chose the ‘Lotus’ name remain obscure to this day. The Lotus Mark 1 was built by Chapman with lots of help from his girlfriend and wife-to-be Hazel Williams while working out of a lock-up garage owned by Hazel’s father. The car featured a body that was made from aluminium sheet attached to plywood and, following Chapman’s study of aircraft design and construction, the body was designed to be rigid, light and strong enough to brace the flexible Austin chassis. The Lotus Mark 1 was put to good use in the following year, 1948, with Chapman and Hazel competing in numerous trials around the country.

While Chapman was at university, he had gained his private pilot’s licence through membership of the University Air Squadron and on graduation in 1948 he took up a short service commission in the RAF, mainly, it was rumoured, to continue flying at the Government’s expense. While Chapman was serving in the RAF he built the Lotus Mark II, again based on an Austin Seven and again with Hazel’s help and support, but this time he fitted independent front suspension based on a Ford front axle, cut in half and firmly fixed to the front of the Seven’s A-shaped chassis. At the time, this was a popular modification and was generally referred to as a ‘jelly joint’. At the rear, Chapman showed his ingenuity by combining parts from the two standard Austin Seven rear axles to provide a unique 4.55:1 ratio unit that was ideal for trials. A Ford Ten engine was also procured to give more power and the car was ready for the 1950 season, where it was reasonably successful.

Chapman left the RAF in 1949 and took a job with Cousins, the construction company, but quickly left for a better post at the British Aluminium Company. During the 1950 motor-sport season he and Hazel entered the Mark II in some circuit races. They found that the car was competitive and that Chapman enjoyed circuit racing as much as, if not more than, trials. So his next car would move away from the all-purpose design of the Mark II and would be aimed at circuit racing.

Chapman also decided that this car would be built to compete in the 750 Motor Club’s Formula 750 championship, at the time one of the cheapest ways to enter proper racing and a Formula that was very well supported by the public. The Mark I and Mark II were duly sold in September 1950, providing Chapman with the funds to start on the Mark III. At the same time, Chapman had met the Allen brothers, Nigel and Michael, whose parents had a larger garage and more equipment than Chapman, so the Mark III was built at the Allen parents’ house. The Mark III was, as the regulations demanded, Austin Seven-based, but Chapman designed a bolt-on triangulated space frame, which surrounded the engine at the front of the car and contributed massively to stiffening the original chassis. Made from welded round-section tubing, the space frame had to be detached to change the engine, but it was light and was also utilized to support the simple alloy bodywork, an early example of Chapman’s ability to make parts do more than one job if possible.

Boxing in of the U-shaped sections of the Austin chassis also aided stiffness, and Ford-based ‘jelly joint’ independent front suspension was used, as on the Mark II. The standard Austin Seven side-valve engine also came in for some Chapman magic. The engine’s inlet manifold had only two ports serving the 4 cylinders, an arrangement that was pretty inefficient. Chapman devised a way of dividing each port into two, by judicious removal of metal from the block and the welding in of a central divider that effectively gave an individual port per cylinder. This gave a significant increase in engine power and, when combined with the stiffer chassis, made the Lotus Mark III the winner in many of the Formula 750 races it entered. The four-port head was so successful that the 750 Motor Club altered the rules for 1951 to ban it – something that became synonymous with Lotus innovations and their elegant interpretations of racing rule books in the years to come.

The first true production Lotus was the Lotus Mark VI – a couple of alloy-bodied ones are here with a Lotus 7 behind.

With demand for Formula 750 components and at least one customer wanting a replica of the Mark III, Chapman saw commercial opportunities in his hobby and moved to new premises; these were in fact the stables behind the Railway Hotel in Hornsey that was still run by his parents. At the same time, he formally set up Lotus Engineering Company, which was officially formed on 1 January 1952, despite the fact that Chapman was still working full time for the British Aluminium Company. Michael Allen was the only full-time employee, with Chapman working at the company at weekends, holidays and after he got home from his day job, while Hazel looked after the paperwork.

During its first year, the company built a replica of the Mark III for customer Adam Currie, which was designated a Mark IIIb, produced the Mk IV, which was a Ford Ten engine special based on an Austin Seven chassis aimed at the trials scene for Mike Lawson (who had bought the Mark II from Chapman in 1950) and fabricated numerous components for the Formula 750 market. The Mark V was intended to be a 100mph special aimed at the Formula 750 championship but was never built; while the Mk V was being thought about the new company was already designing the Mark VI as its main money spinner.

The Lotus Mark VI was a very successful competition car. The alloy body sits on a sophisticated tubular space-frame chassis.

The Mark VI moved away from the 750 Motor Club Formula and was aimed at the more mainstream sports-car motor-racing classes. Chapman had already swept all before him in the 750 Motor Club and was looking for new challenges and new markets for his young company. The Mark VI is often referred to as the first true Lotus, as it had a Lotus designed space-frame chassis, while all the previous Lotuses were based on Austin chassis, albeit often modified beyond recognition. The space frame was built from square- and circular-section tubing, was welded together and the alloy bodywork was riveted to the frame to provide additional bracing. The front wheels were outside of the bodywork, with small alloy cycle wings used to maintain legality, but at the rear the wheels were fully enclosed by the bodywork, giving an attractive and distinctive appearance. The Mark VI still used a Ford pivoted front axle that was split to provide independent suspension, but it used a combined telescopic damper and concentric spring to control the suspension, an innovation that was just starting to appear on the rear suspension of motorcycles in the early 1950s. At the rear, a Ford solid axle was used and the brakes also employed Ford components.

The Lotus VI was a competition car that could be used on the road so had minimal bodywork and no weather protection. At the front, a split Ford axle gave independent suspension and coil spring over-dampers controlled wheel movement.

In July 1952, the first Mark VI was badly damaged in an accident – it hit a milk float that came out of a side turning and the car was a write-off. However, the insurance on the car paid out and at the same time Michael Allen decided to leave Lotus, taking the wreckage of the first Mk VI in exchange for his share in the company. At this point, Chapman set up the Lotus Engineering Company Limited with just him and Hazel as the directors, still based in the stable block behind the Railway Hotel. Chapman also gathered a band of mainly unpaid but enthusiastic helpers, which included employees of the de Havilland aircraft company based just up the road from Hornsey at Hatfield. These enthusiasts included draughtsmen Peter Ross and Mac McIntosh and also, significantly, the Costain brothers, aerodynamicist Frank and engineer Mike.

The replacement for the VI was the Lotus VII. It retained the tubular space-frame chassis, but had glass-fibre wings to simplify production.

With production of the Mark VI starting, Chapman realized that he could avoid having to charge customers an additional 25 per cent purchase tax on top of the price of a compete car if he produced the Mk VI as a kit of parts which the customer would then build up supplying some components themselves. The production of the Mark VI chassis was subcontracted to the Progress Chassis Company, run by Chapman fans Dave Kelsey and Johnny Teychenne (a schoolfriend of Chapman) and based in Edmonton, North London. Each completed space-frame chassis was delivered to the Hornsey workshop for the body work, wings, stressed panels, nose and grill to be made up and fitted. The kits could contain anything from a chassis with all the stressed bodywork fitted upwards, and the customer was left to fit the engine, transmission, front and rear axles and the interior to have a complete Lotus.

The Mark VII label was put to one side at the time to denote a replacement kit car for the Mark VI that Chapman was developing, plus Chapman changed his model designation from Roman to Arabic numbering after the Mark VI. The next car to be built in amongst some 100 or so Mark VIs was the Mark 8, which was ready for the 1954 season. This was a space-framed racer with full-width aluminium bodywork, a 1500cc MG engine, a de Dion rear axle and was probably the fastest 1500cc sports car then competing in the UK. The bodywork had been aerodynamically tested by Frank Costain and was very slippery, adding significantly to the performance of the car. It was at this time, early in 1954, that Team Lotus Ltd was set up as a separate company to race the Lotus product. While the prototype Mark 8 was fast, it also was so stiff that the chassis would break rather than distort when subjected to abnormal loads (that is, when it crashed) and the use of high-tensile tubing and brazed joints meant that the tubes could and did break by the brazed joint.

A logical progression from the VI was the Lotus Mark 9. This had all-enveloping bodywork and led to the development of the Le Mans-winning Lotus Eleven.

While all this was going on, Chapman also found the time to marry Hazel on 16 October 1954 and he also left the British Aluminium Company to work at Lotus full time. Due to the problems experienced with the prototype Mark 8 chassis, the production Mark 8 used an adaptation of the Mark VI frame, with additional loops to support the all-enveloping body. In total, eight Mark 8 cars were made and it was superseded by the Mark 9 in March 1955, which had a simplified and lightened chassis still based on the Mark VI. One of the two ‘Works’ Mark 9s was powered by a new all-alloy 1100cc Coventry Climax engine. This was the Feather Weight A or FWA, which was designed by Wally Hassan and Harry Mundy, and signified the start of a long relationship between the Coventry-based engine manufacturer and Lotus. Lotus also formed a third company in the early 1950s, Racing Engines Ltd, to concentrate on engine and gearbox work.

In 1955 the Mark 10 was introduced, basically a Mark 9 that could handle a larger engine. So Lotus was forging ahead, growing significantly and maturing as a company. In 1955 the company had enough time and money to exhibit at the London Motor Show at Earls Court, albeit as an accessory manufacturer, as Lotus was not a full member of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, which ran the show. The Lotus Type Eleven (so called to avoid confusion with the Roman numeral ‘II’) was introduced for 1956 to replace the Mark 9, and was offered in three guises: the Le Mans with Coventry Climax FWA engine, disc brakes all round and a de Dion rear axle; Sports, again with the FWA engine, but drum brakes and live rear axle; and Club, which shared the Sports specification but had a Ford 1172cc engine. The Eleven featured a space frame and full-width bodywork, designed by Frank Costain and hence very aerodynamic, and Team Lotus ran three at Le Mans that year, one of which finished seventh overall and first in its class.

The rapid pace continued into 1956, when Lotus moved into more serious racing, with designing and building the Formula 2 single-seat Mark 12 and also giving Formula 1 teams Vanwall and BRM consultancy work on chassis design and aerodynamics. There was also an updated Eleven, called the Eleven Series 2 rather than the Mark 13 (for obvious reasons), with new wishbone front suspension and many other detail changes, plus more successes at Le Mans. While the Formula 2 Mark 12 was not particularly successful, the Eleven returned to Le Mans in 1957 and an Eleven, powered by the specially prepared Coventry Climax FWC engine that was basically a short-stroke FWA with a mere 750cc capacity, won the Index of Efficiency. On top of this success, a second 1100cc Eleven won its class, and to cap the year off the Type 14 Elite GT car was announced at the 1957 Earls Court Motor Show, alongside a more production-friendly replacement for the Mark VI in the shape of the Lotus VII.

The Lotus Elite (Type 14) was Lotus’s first attempt at a true GT car. Not only was it considered to be one of the best-looking cars in the world, it had a monocoque shell made from glass fibre.

The Elite was successful, with over 1,000 units sold.

Predecessor of the Elan – The Lotus Elite

In the mid-1950s, Lotus was at a turning point. Having produced a series of successful racing cars, and with over 100 Lotus VIs produced, Colin Chapman wanted to break into the road-car grand tourer (GT) market. This aim was met by the design and production of the Lotus Type 14, named the Elite, which was announced to the world’s press in 1957.

By this time, the traditional car construction of a separate steel chassis that carried the power train and suspension with a non-structural body placed on top was being superseded by the mainstream manufacturers with the unitary or monocoque type of construction. This meant that the bodyshell was made from a number of steel pressings welded together to give a one-piece structure that formed the body and replaced the separate chassis and bodyshell. The suspension and mechanical elements were bolted directly to the monocoque shell. This type of manufacture lent itself to volume production, but the costs to produce the various and complex tooling for the pressings and to buy the necessary large and powerful machinery were high, and far too expensive for a small company like Lotus to contemplate.

However, glass-fibre-reinforced plastic (GRP) technology was emerging at the time and was being used by other manufacturers to produce the bodies for low production run cars that utilized a separate steel chassis, such as the Jensen 541 and the Daimler Dart, and to produce kit car bodies that owners could fit to an existing or purpose-built chassis. Chapman, with his eye for innovation, had taken to the new material and studied it in depth, establishing that it had the strength and stiffness required for use in the structural elements of a vehicle. He also realized that in order for the material to be used in that way the whole vehicle structure should be designed from the outset to utilize the material, as its characteristics were very different from those of steel.

One of the major advantages of GRP was its light weight for a given strength – equivalent structures in GRP (or other composite materials) could be lighter and as strong as equivalent steel structures, as long as the GRP structure had been designed properly – a use that was successfully demonstrated by the Elite. A second major advantage of GRP was that it was relatively cheap to produce limited numbers of mouldings, while a steel structure required expensive tooling of formers and presses to produce shaped-pressed steel body parts, which then had to be welded together to produce a finished unit. While using steel panels made sense for mass-produced cars, where the large numbers of cars made and sold could offset the high cost of the tooling, for a relatively low-volume manufacturer like Lotus the overheads to produce a set of moulds and hand-build a bodyshell by assembling the GRP mouldings taken from the moulds were relatively low and hence affordable.

A pair of Elites enjoying the sunshine at Club Lotus’s Castle Combe track day in 2012.

The Elite was a two-door Coupé aimed at both road and racing use. Chapman and the Elite’s stylist Peter Kirwan-Taylor identified a number of design criteria for the Elite – the first was that it should be suitable for road and rally use, but the second was that it should be capable of winning its class at the Le Mans 24 Hours race. The others related to its construction. Using an all glass-fibre monocoque, its suspension was to be based on the Formula 2 Lotus 12, the engine would be the new Coventry Climax FWE (Feather Weight Elite) engine and the cabin size would accommodate two average sized adults – with Chapman himself acting as the model. Fully equipped as a road-legal car, the Elite was virtually unique at the time, as it used GRP for the entire bodyshell, which was a monocoque design with no separate chassis, albeit with some steel reinforcing plates bonded in at strategic locations. The Elite was light and rigid, with great performance, and handled superbly. It was judged to be a very successful competition car. As a measure of its success as a competition car, the Elite won its class at the Le Mans 24 Hours race every year from 1959 to 1963. However, despite its success at Le Mans, the major road race of the time, the Elite’s credentials as a road car, especially a grand tourer, were undermined by its relative lack of sophistication – most notably road tests of the day found it to be noisy and hence tiring to use for covering long distances.

One of the most famous racing Elites – nicknamed ‘Daddyo’ from the registration number ‘DAD 10’, this Elite was raced during the 1960s by Les Leston with much success.

The Elite was powered by the Coventry Climax FWE – Feather Weight Elite – an engine that was light, reliable and powerful but expensive.

Chapman acknowledged that the Elite was in fact 60 per cent racer and 40 per cent road car. Probably more important than the lack of refinement was the fact that it was very expensive to make. The body was complex and difficult to produce, while the engine was a specially designed 1216cc Coventry Climax FWE unit. This 4-cylinder engine was over-square with a bore and stroke of 76.2mm by 66.7mm and sported an all-alloy head and crankcase with a single overhead camshaft. The complete engine weighed a mere 215 lb (97.5kg), justifying its name and assisting Chapman in his pursuit of lightness. The engine produced 72bhp in its initial single SU carburetted form, and later produced a healthy 83bhp when fitted with twin SU carburettors. It also had reasonable torque of 77 lb ft at 3,800rpm, plus was easy to tune if required. The only problem with the engine was that it was virtually a hand-built racing unit and therefore expensive.

The production of the complex bodyshell was also done by outside firms, the first approximately 250 shells being produced from early 1958 by Maximar, a boat-building firm based in Sussex that had good experience of working with glass fibre. However, after experiencing problems with production delays and quality, body production was switched to the Bristol Aircraft Company during 1959 and 1960, which resulted in fewer delays and a better product. However, the Elite bodyshell, like its engine, was an expensive component and Lotus had to pay for Bristol’s profit margin as well as the body itself. The outsourcing of body and engine meant that Lotus could not drive down the costs of producing the Elite as efficiently as if the work was done in-house, so this became one of the areas that the Elite’s replacement would have to improve upon. The Elite was officially in production from 1958 to 1963, although limited numbers of the cars built up from spare bodyshells were sold until the mid-1960s. Just fewer than 1,000 cars were produced, but as the cars were complex to build and the monocoque body and the Coventry Climax engine were both expensive to buy in, the price charged for the car had to be high, which obviously limited the car’s appeal.

Some sources state that Lotus was believed to have made a loss of over £100 on every car produced, although others say that the claimed loss was a useful accounting trick to disguise the real state of the company, so the actual financial influence of the Elite on Lotus’s finances must remain questionable. In any case, the car had proved that a market for a small, relatively refined road-going sports car was there. Importantly for what was to come, the Elite had introduced the use to Lotus and the general public of glass-reinforced plastic in the production of a ‘proper’ road car, rather than a thinly disguised racing car. So a replacement road car for the Elite was needed, which needed to be cheaper, easier to produce and could make a profit for Lotus. That car was the Elan.

The basis for the Elan was its simple pressed-steel chassis – light and rigid, it carried all the stressed parts of the Elan, that is, the engine, transmission and suspension.

Lotus Elan Production History

By the time the Elan came into production, Lotus had been split into four companies – Lotus Cars, Team Lotus, Lotus Components and Lotus Developments – as well as another ‘paper’ company called Racing Engines. While Team Lotus ran the racing team, Lotus Cars Ltd was responsible for the production of the Elan road cars and Lotus Components was responsible for the production of all the sports and single-seat racing models, including some of the Elan 26R and Lotus 7 production. Racing Engines supplied the engines and transmissions of the cars supplied as kits, and Lotus Developments was responsible for new products. Under this organization, the Elan was designed and readied for production.

When the Elan first made it into production during May 1963, construction of the bodyshell was contracted out to Bourne Plastics, based in Netherfield, Nottingham, some 127 miles north of the Cheshunt factory. Bourne started body production with moulds supplied by Lotus and the company was contracted to supply 1,000 bodies at a rate of twenty per week. However, it struggled to meet this target, having delivered only some 200 shells by August 1963. Lotus therefore decided to terminate the Bourne contract and take body construction in-house. More space was needed for this, so it bought premises in Delamare Road, close to the Cheshunt plant, to use as a dedicated body shop. The body moulds were relocated to Delamare Road and bodyshell production recommenced during September 1963.

The Elan’s body was glass fibre and unstressed. It was also very attractively styled and pop-up headlamps were fitted to meet legislation for minimum headlight height without ruining the lines.

The Elan chassis manufacture was carried out by John Thompson Motor Pressings based in Wolverhampton. This company produced all of the original Elan chassis, while the Plus 2 chassis were manufactured by Guys of Sunbury. Elan engine production was slightly complicated, as the bottom ends were supplied by Ford from its Dagenham plant in East London and these were delivered to the Villiers/JAP plant in Tottenham, North London. The cylinder heads were cast in the Midlands by William Mills and these were then delivered to JAP for machining, with JAP building up the complete engine for delivery to Lotus.

Villiers, who had bought JAP in the early 1960s, then closed the Tottenham plant and shifted Lotus engine production to the main Villiers plant in Wolverhampton. These disparate manufacturing operations came together at the Cheshunt plant where the cars were assembled. While the factory could and did supply the Elan fully built, a good proportion of Elan customers bought the car as a kit, keeping alive the practice first exploited by Chapman with the Mark VI, which meant there was no purchase tax to pay. A factory-built Elan S1 would cost £1,499, while the kit version cost £1,095, saving some £404, made up from the saving in labour cost and purchase tax, a significant amount at the time. Buyers of the kit-based Elan would receive two invoices – one from Lotus Cars for the body, chassis and suspension parts and one from Racing Engines for the engine, so as to avoid problems with the UK’s Inland Revenue as this helped to ‘prove’ that the customer was buying a kit of parts from more than one legal entity. The kit came as a fully built bodyshell, with the boot, bonnet and doors attached, as well as all the ancillaries including the brake and fuel lines, glass, lights, instruments, switches, steering column, wiring loom, seats, trim and windscreen wipers fitted and bolted on to the chassis. The differential, rear driveshafts, hubs and suspension were also fitted.

The Elan Series 1 interior was fairly basic, but had all the important elements. The side windows were frameless and were pulled up or down using a chromed fitting on the top of the glass.

The engine and gearbox, propeller shaft, exhaust system, radiator, front suspension and wheels (with tyres fitted) came as separate components for the new owner to assemble to the chassis/body unit. So all the customer had to do was fit the separate bits, bleed the brakes, fit the radiator and plumb it in, then fill up with oil and water and they were good to go. Once completed, a new UK owner had to register the Elan as a new vehicle and when the registration number was allocated, the car could be driven on the road. A post-installation check was included in the price, which was carried out by the local Lotus dealer. An Elan kit would not take too long to assemble – in fact, a famous Lotus advert of the time described how a Doctor Hammerton took a mere weekend to build his Elan, assembling the front suspension on Saturday morning, fitting the engine, radiator and exhaust before dinner, then fitting the number plates, checking tyre pressures and filling it with oil and water before driving to the pub for Sunday lunchtime opening time.

An article in Motor magazine (30 April 1966) also describes the build-up of an early Elan Coupé. The kit was delivered on the Thursday and work started on the Saturday, with the purchase of oil and brake fluid and much reading of the instructions and the Lotus workshop manual. Physical work actually got going on the Sunday, with the front suspension and brakes fitted by 12.30pm; by 3.15pm the engine was in after a lot of manoeuvring and effort to persuade the gearbox actually to go into the chassis tunnel. To fit the prop shaft, the team found that the access hole in the body was needed to guide the shaft into the box, which meant removing the driver’s seat and some carpet. They also found that they had to take the carbs off to connect up the fuel pump, so packed up working at 9:00pm with the engine in and connected, but the carbs still on the bench. On Monday the radiator, exhaust and carbs were fitted, then a lot of tidying up was done, including bleeding the brakes several times. At 7:45pm, they tried to start the engine. After finding that there was no fuel getting to the engine, and tracing this to the fuel tank outlet pipe being disconnected and a boot full of petrol, the engine was fired up by 9:30pm. There were a few minor issues, but the car was completed in 55½ man hours over three working days, and in the tradition of British rebuilds they had one part, a 17mm copper washer, left over.

Individual round rear lights and a recessed boot lid are features of the Series 1 and early Series 2 cars.

In 1965, it was clear to Chapman that Lotus had outgrown the Cheshunt plant and the Delmare Road body shop, but the local council had decreed that no further expansion of the sites would be permitted. Not only did the company need more space, but Chapman also stipulated that Lotus needed its own test track, as the Cheshunt local council had received may complaints about the noise caused by Lotus testing its cars on the local roads. A site based on the ex-RAF and USAF bomber base at Hethel in Norfolk was available, so Lotus acquired this in 1965. With Lotus in a reasonably flush state for once, a new purpose-built factory was added, alongside the airfield runway and perimeter tracks that were to be used as a test track, storage area and of course a company-operated airstrip – since his RAF days, Chapman had remained a keen private pilot and often flew the company aircraft to suppliers and race meetings throughout Europe.

The move was phased, initially with the body manufacturing plant going to Norfolk in the spring of 1966, taking over some refurbished existing buildings while the main factory was being constructed. Built-up Elan bodies were shipped back from Hethel to Cheshunt for final assembly, before the full move to the almost completed new factory was achieved in November 1966. Eventually Lotus set up its in-house engineering and machining shop by early 1967, when initially the preparation and machining of the bare twin cam head casings was undertaken before shipping them to Villiers for assembly of the complete engines, then in August 1967 the contract for production of the twin cam engine by Villiers was cancelled and full production of the engine was brought in house. By this time, apart from the chassis and sundry items such as the gearbox and various ancillaries, complete Elans were being built totally in-house by Lotus.

This not only added to Lotus’s credibility within the motor industry, signifying its acceptance as a ‘real’ production car manufacturer, but it also meant that most of the major cost items were produced by and under the control of Lotus. The company was able to reap the benefits of doing all the work internally and at long last did not have to pay more than was necessary for the parts that made up the Elan. The move to Hethel also gave Lotus enough space to start production of the Plus 2. The introduction of the Plus 2S in 1969 marked another major milestone; the Plus 2S was the first Lotus car not offered to the public as a kit for home-build. Elan production continued at Hethel until the original Elan was dropped from the range in August 1973 and the final Plus 2S 130 models were produced there in December 1974, whereupon production switched to the new upmarket four-seater Elite.

Lotus Elan Design

The design of the Elan was started in the very late 1950s, when the need for an Elite and Seven replacement was recognized. The original design brief for the new Lotus, which would become the Type 26 Elan, was for a basic sporting road car from the start, rather than a straight replacement for the somewhat exotic Elite. Initially, design studies for a new Lotus road car were aimed at it being a more road-oriented Lotus Seven replacement, with a space-frame or monocoque chassis, minimal glass-fibre bodywork and using standard small Ford engine and running gear, including a live rear axle. However, it soon became apparent that such a car would be less well equipped than a frog-eye Sprite (even a frog-eye had doors), but would also have less performance and cost more. So the design parameter evolved, and a more upmarket car was soon envisaged, with a ‘proper’ glass-fibre monocoque body (albeit still open-topped), but with proper doors and using more sophisticated suspension. The emergence of the Lotus Twin Cam engine based on the Ford 1500cc unit also meant that a relatively low-cost, but sophisticated, engine unit was available and this in turn pointed towards more design sophistication and a more upmarket placing; not quite an Elite replacement, but a car that was a cut above the mass-production opposition. And so the new design started to take shape.

One of the major features was to be the monocoque glass-fibre body, but with proper doors and no roof the design team struggled to come up with a design that had adequate rigidity. Ron Hickman, like Chapman an engineering innovator of the highest order, suggested that a slave chassis be created to test the running gear and Chapman famously designed the Elan’s backbone chassis in a couple of days. The design was a radical move from the existing Lotus chassis technology, as it was constructed from folded steel sheet rather than being a tubular space frame. This meant it was very simple to fabricate and relatively light.

The prototype chassis was designed around the Twin Cam engine, Triumph Herald type double wishbone front suspension and Lotus’s own single lower wishbone and coil-over damper strut type rear suspension. The slave chassis and running gear were clothed in a cut-and-shut Falcon Caribbean glass-fibre body (a popular kit car of the time) and were used during 1961 to test and refine the mechanical elements of the design. In the meantime, the body team realized that the chassis was light, cheap and rigid and could do the job of supporting all the mechanical components without having a monocoque body, so set about designing a body that could take advantage of the new chassis.