Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Salt Modern Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

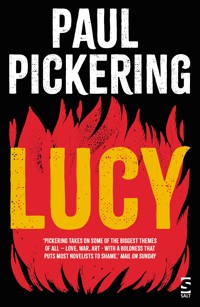

Paul Pickering's new anti-war novel Lucy is about obedience and rebellion, how one survivor in the actual and moral wasteland of immediate post-war Berlin takes over the lives of three others, psychologically and sexually, in the way Hitler took over a country. The worldwide protests surrounding the 2024 conflict in Gaza mirror the rebel spirit at the heart of Pickering's important, groundbreaking novel. Set partly in a German kibbutz, started by Nazis to remove Jews, there is a clash between utopian ideas and the toxic nationalism necessary to found the state of Israel. Operation Lucy, once an idealistic, anti-Nazi espionage ring, of which all the main characters are part, has become a self-devouring monster. Lucy is darkly comic, showing how best intentions, when they pass through the looking-glass of human failings, change to the opposite. Joseph Heller's "Catch-22" means no escape because of contradictory rules, "Lucy" is the Lucifer paradox, where the only good is bad, and only bad is good. A thrilling, disturbing and utterly compelling read from one of the UK's most celebrated authors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 585

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

for Alice

vi

“No one has the right to obey.”

Hannah Arendt

Contents

Part One

I

I am free. The words rolled through him like thunder as naked and dark blue with dust he fled from his own all-consuming yellow fire.

He emerged from a ruined building a human flame and with one long scream ran up a mountain of rubble and destruction, the small arms fire chattering to a stop under clouds blackened with smoke and by the light of a strange and pale red sun.

There was an immense battle and he was not clear, his mind and memory gone, what he was doing there, or who the sides were. Or who he was. The hot dust stung his lungs.

The man tried to beat out the fire on his legs and chest and on the back of his left hand and stared up at the sky in a halo of his own flames and pain. His nakedness brought an intimacy to his inevitable death on a day when tens of thousands died. All reason then disappeared in another long scream.

Those watching missed a breath. Only a few women in brown uniforms by a red banner laughed at his infant nakedness. Men shook their heads. In his personal torment he was so completely vulnerable and magnificent as to be absurd in the faceless murder of the fighting. Too alive yet to die.

No one shot at him, or could tell which side he was on, although he came from the far end of the square, and there was a ragged cheer from among the huge blocks of stone and pillars that had exploded off the massive buildings. Several believers in their brown uniforms anxiously made the sign of the cross, interpreting his halo of fire as the devil’s horns. 2

He raised his arms to the heavens.

Around him the grey rubble became horizons of smoky indistinction and indifference.

His arms outstretched, the man was trying to get the fresh spring air into his seared lungs, one last time, and onto his raw and charred skin.

His brain tried to work in the bubbles of consciousness between pain.

Through the smoke there was the glow of many fires. He knew at any second the spell of his sacrificial image might fail and a soldier would shoot him for no other reason than he presented a good, stationary target.

Yet in his ordeal he was so close to everything; at one with the soldiers who watched, and even with the broken statue as he reached the top of the hill of lesser stones. The statue had a three-cornered hat and a knowing smile on what now was only half a head. Yes, he was free, if only to fall down the other side of the small mountain, dead. And that was enough.

In his clenched left hand was something precious.

Then, without warning, the hill of stone he stood barefoot on, with the broken statue, was hurled into the air again and the colours and smells and tastes and pain vanished.

II

“Holy shit!where are you, man?”

A young American colonel sprinted into the blue-grey smoke that had been a hill of rubble and waited for the dust to clear. He had seen the burning man from afar and knew he had to save a heretic angel who had not given in to the surrounding madness. The colonel blinked away the grit in his eyes and found himself looking at an unconscious, naked man who had been terribly burned down the left-hand side of his head and body. The man had several wounds to his chest and there was a large hole in his skull; it was possible 3to see the pearlescent yellow-white folds of his brains. Yet he began to move. He was breathing. He opened his good eye.

He had an erection.

By the man was what looked like half the head of a statue of Frederick the Great. The colonel smiled. “Who wants to live forever?” he said, out loud, quoting the playfully ambiguous question to his troops by the King of Prussia. The colonel looked at his watch. It was exactly four in the afternoon on April 30, 1945, in the last days of the siege of Berlin, and what every sane person hoped was the end of World War II in Europe

The colonel had no idea where the last huge explosion had come from, which side had dropped a bomb or fired a shell, but then, a couple of yards away to his left, two Russian paratroopers shook their brown-clad bodies free from under the plaster and bricks. They must have heard him.

He levelled his pistol as one paratrooper, a man with sergeant’s stripes, cocked his papashasubmachine gun and pointed it at him while barking a command. The second paratrooper, a private, no more than a boy, turned his weapon at the man on the ground, smiling at the erection, but glazed over with the same fatal obedience as when ordered to kill one of his father’s pigs.

“Please stop!” came a shout behind them. “Pozhaluystaostanovis’!”

The private spun around. But the Russians did not fire. It may have been the use of the word “please” that startled them. The speaker nervously held a white handkerchief on a stick. Behind him was a small group of soldiers with American flag patches on their uniforms and for several more seconds the two sides aimed their machine guns at each other, breathless, terrified.

The colonel then dropped his pistol to his side, smiling and showing his white teeth, and took a packet of cigarettes out of his pocket. His long blond hair hung down below his helmet where someone had painted Hollywood in flowing script to one side of a silver eagle denoting his rank as colonel. The cigarettes were Lucky Strike. The red circle on the front of the packet shone like a ruby. 4He threw them to the Russian private, who caught them easily with one hand. A tall, angular American soldier ran past the Russians to the man on the pile of rubble. The soldier had a Catholic chaplain’s cross on his shoulder straps.

“This wretched man’s still just alive. My God, he is… aroused.” The priest picked up a cheap brown coat lying close by the man and grey with dust. He began to rub at the coat to expose a yellow badge. “There’s the Star of David on this coat. If it’s his, he may have been a prisoner in Gestapo headquarters, over there. He has the Jewish star. He’s trying to say something in German. About love.”

The young colonel’s clear blue eyes had the innocence of the altar boy he had once been. He nodded. The priest was with them because he spoke good Russian and, Kells thought, to make the mission more idealistic than it was.

The man’s infectious bid for freedom had even stopped the butchery for a moment or three. That had to be worth something.

“Tell the comrades we want this man. We are an observer unit trying to track down Americans who were being held and tortured in the Gestapo headquarters, near Mr. Hitler’s bunker. We’ve clearance from Marshal Konev. Yeah, I see they know that name. We want to ask the burned-up man about our boys. This man is harmless and nearly dead. If they give him to us, we’ll give them more cigarettes and chocolates. I’ll get them Mae West’s phone number from my cousin who’s in pictures. How’s about it? Is that a deal?” He talked fast and loud because he was shit scared and afraid he might dry up as a bullet zipped past.

The two Russian soldiers listened without emotion while his words were translated by the priest.

One turned to the other and shrugged. Americans were not officially meant to be in Berlin and the Russians, especially the private, looked as if they did not entirely believe in them, as they no longer completely believed in saints and angels.

Before the Russians could answer, there was another barrage of shellfire that landed in the park to the south and set fire to an asphalt 5path. The Zoo Flack Tower, a bulbous, dark, medieval-style keep that loomed on the horizon, raked the ground with fire from its anti-aircraft guns. The young colonel felt the heat on his face as most of his men hit the ground. The Russian private ran forward and grabbed the packets of cigarettes and chocolate from an orderly standing by the colonel and with his sergeant disappeared like rats into the labyrinth of desolation. Two more American soldiers appeared from the shelter of a nearby doorway carrying a stretcher.

“We got to get out of here before those Russians eat the chocolate and want Mae West,” said the colonel, pleased.

Colonel Kells “Hollywood” Vardy was twenty-five years old and had been shot at now for nine months and twenty-four days and knew no one got past six months without a serious wound. That was not cool man, as the black guys in his unit said. But he had to save the burning man.

“If things fucking fall apart, at least bring something back,” the infantry general had said. The colonel had expected to find the men he was looking for in the Swiss Embassy on Posierplatz, but there did not seem to be anything much of Posierplatz left. Maps are only any good when there are streets and buildings. There did not seem to be much of anywhere left and he had openly contradictory orders from military intelligence not to let the men in the embassy, in particular a Hyman Kaplan, fall into Russian hands as they had gone over to the other side, whichever that was, and to do whatever was necessary.

The colonel did not like this leaden “wink-wink-nudge-nudge” double talk. Killing resistance fighters was totally wrong, but if he objected, he might have bought all of them a boat ride to the Far East.

Still, the killing of the real Hyman Kaplan had most certainly been done for him.

The Russians were killing everyone. Sometimes, as with the last barrage, they killed each other. They even shot the animals in the Tiergarten Zoo. The colonel had seen two dead zebras and a strange kind of ostrich among the human bodies by the Ostrich 6House, which was a fake Egyptian temple covered in hieroglyphics painted in yellow, blue and red. The primary colours howled out of the black and white newsreel of a day. It was like something from a studio film set he had been on with his writer cousin, after a surfing trip to Malibu Beach. The animals, not the men, made him feel sorry and angry and he said the “Ave Maria”, though he had put his Catholic upbringing on the other side of a glass screen many years ago because it became too hurtful.

Kells lit a cigarette and stared at the awkward boned priest. He was a young man with an over-prominent Adam’s apple and despairing eyes.

“This poor soul has been through a lot. My God. How’s man expected to live such a life? He has something in his hand… It’s almost too burned up… I’ll be damned… It’s the dried petals of a white flower.”

The colonel smiled back, wistfully. “We fight on the side of romance! It may bring us luck …”

He fingered the Mickey Mouse Club badge he had in his lapel. His mother had given it him for luck when he went to high school.

He noted the disapproval of his new Italian sergeant, who was wearing a brown leather jacket and had a gold eye-tooth. You weren’t meant to mention Luck. His sergeant did not think he took things seriously, that he did not pay war its proper respect. The colonel glanced around him as a bullet hissed past.

The intelligence operation they were part of that day was so fucking secret no one, not the army nor the intelligence people, had told him its name.

He had not felt part of this lunacy since parachuting into Normandy and had sleep-walked through his command. He felt no guilt, no need for absolution. Nothing.

The war was behind another wall of glass. Until today. Kells was fascinated with the burning man.

The wounded man was put on the stretcher and the colonel flicked his cigarette away. They dodged and ran through the Tiergarten 7and, now and again, amid the smell of burning and cordite and high explosive, there was the scent of blossom on the hot spring wind.

“Did you catch what the burning guy said?” Kells asked the priest, when they stopped behind a line of trees.

“It did not make sense.”

“I doubt if it would. Try me.”

“He said, ‘IchliebeSiealle’, I love you all.”

“Christ,” said Kells.

“Exactly, if I may say so,” said the priest, with a smile.

III

Two and a half weeks later, the young colonel sat at the back of a light and airy green-painted room watching the man he had rescued slowly inhale and exhale in hypnotic, measured repetition. Kells’ mouth kept falling open in childlike wonder. When he was young he might have called it a miracle. It was a miracle. From first sight the event had taken hold of him and he had not been able to get the transcendent image of the burning man out of his mind. Or the white flower gripped hard in a burnt hand. Or the words “I love you all.” It spoke to everything Kells believed in before the war. At last there was something good… Kells had done good… A card in neat lettering was pinned at the end of the white tubular metal bed.

Kaplan, Hyman, type A blood, c. 35–50 years old? Condition: critical.

Propped on the cool linen pillows of an American military hospital outside Bonn was the man to whom Kells had given that name. The unconscious patient had a calm, beatific expression on the part of his face not in bandages. His head was covered in white lint and cotton wool and so were both his hands and arms and the left side of his body down to his left leg, secured to angry red-purple flesh with tape. There was a large cotton wool bandage over the left eye. His nose was broken and badly burned and had been covered in purple iodine. Kells fidgeted on his chair. 8

The man, even unconscious, had a weird magnetism and Kells was delighted for him and astonished at his survival, but personally there were complications.

The army were pleased with Kells, but he was going to be up to his neck in shit and trouble from the intelligence people for bringing Hyman back alive at all, and more so if they found ‘Hyman’ was someone else. Kells had disobeyed their orders, however ambiguous, euphemistic and army-speak, and had then wilfully deceived everyone that his rescued prisoner was Hyman Kaplan. From good intentions, Kells was in a steaming pit of deepest dog-excrement. In France, men had been shot for trivialities like getting lost. Kells had already come close. At least a firing squad was quick compared to a posting to a snake-infested death or glory island in the Pacific, where not even his Mickey Mouse Club badge might save him.

He sighed. He found it strange to be in a pressed new uniform and back in the “world”. But whatever voodoo doo-doo he was in, he was righteously glad the burning man was alive.

It was now impossible for the man in the bed to disappear.

The newspapers and wire services had been kept from his bedside, but at a press conference the day before, Hyman Kaplan had been rightly declared a hero of the Jewish resistance and already given medals by France and Italy. It had been discovered Hyman Kaplan had been a distinguished professor at Berlin university, specialising in the Old Silk Road and the textile itself. He was an expert on the cultivation of silk, the silkworm and moth and held two doctorates on how its production had affected civilisation. Captured once, he escaped from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp north of Berlin and took part in a vital intelligence operation, the same operation that had been sent to kill him. The operation was simply described at the press conference as “vital to a new and peaceful world”.

A reporter in the press conference started to ask a question about the operation, but was cut short when another wanted to know if it was true that the man had an erection, naked, on the battlefield. There was laughter. But a tall, dark-haired woman, who appeared 9to be a German interpreter with the French delegation, jumped to her feet, angry and lovely:

“How dare you! This man is a hero. I think you had better leave,” she shouted in English.

Kells watched fascinated as a rangy newsman stood, smiled and dutifully left the room to applause. At the reception afterwards the woman had come over to Kells.

“Darling, I want to say you deserve your medal for saving that man,” she said, and he had asked her to dinner, but she had looked disappointed and explained she was from Berlin, and he had smiled and said he was based there. They had stared at each other for what seemed an age.

Her skin was a pale ivory and had a luminous quality, a beauty that came with Berlin malnutrition. He then noticed that her black suit was mended and there was a small tear at the front of her blouse. Her high-heeled shoes were scuffed, but there was a visceral danger about her in that hand-grenade of a smile that made him blush. Her large brown eyes, one with green flecks, were wicked and playful and she had a dimple at the corner of her wide mouth. A gap between her two very white front teeth denoted passion. There were already lines of both sleep deprivation and laughter on her twenty-something face, making her look more sophisticated. Her eyebrows were arched and her lashes long and curled. She stood very straight and had the entitled but fun-loving air of a powerful mistress at a Prussian court.

She fingered his tie, her breath smelling of violet cachous, and said, “I have to go now, darling. I’ll be back in Berlin in a few days. I’m in the Café Kranzler on the Ku’damm late Friday afternoons. My name is Gretchen. I sing in what’s left of a club around the corner. You can buy me a hot chocolate. I have never had a hot chocolate with a real American hero.” Her voice was lazy and deep. Then she was gone in a haze of no doubt second-hand, looted perfume, from the same ruined bedroom as the violet cachous and high heels.

Kells was left trying to frame a reply, but the muscles in his mouth would not obey him.10

He had also tried to date a girl who was a nurse at the hospital. He had had no female company since Normandy. It was difficult as when he had leave he always had to look after his superior’s wants or to organise something pointless for the men.

He had asked the delicate, freckle-faced nurse with red-gold blonde hair in a long shower of curls to come out with him on the first night he was here to see Hyman. Her eyes were a sea-green blue and he had assumed she was from a church-going Massachusetts town, of Scandinavian descent, or German. She had an aura of goodness. There had been a look of both panic and wonder in those eyes, like a child seeing the ocean for the first time.

Her sweet and innocent smile had lit up her scrubbed face and the room, and Kells. “Yes. That will be good,” she said, in English.

They had gone to a PX restaurant, a cafe really, next to the hospital, and the food had just arrived when she rushed away, knocking a fork from the table in a clatter of big, white nurses’ shoes. One of the waitresses told him in a whisper that the nurse had been in “the camps” and none of them could keep food down, even the ones they let work. And that she was Jewish. The waitress lingered on the word, as if as a warning. The nurse was called Rachel and was quite tall and painfully thin. There were dark circles under her eyes. Her cheekbones and hip bones were sharp as axe blades. There was a small, lozenge-shaped scar on her right cheekbone. She did not look Jewish.

Kells stood up as she now wobbled into the room on those white tea-pot nurses’ shoes in a white uniform with the surgeon who had operated on the man in the bed. Her lipstick was very red. It shone in the green room like a magic lamp. She smiled at him, fluttered a delicate hand and then, to his dismay, left.

The surgeon, a gentle man in blue medical scrubs, stood by the bed.

“You wanted to ask me some questions, colonel? Well, Dr Kaplan, is certainly a lucky, lucky man. The wound to the head in itself should have killed him. It would have killed a moose. We call them 11elk. I have killed mooses many times with such a shot. My family is from Sweden. A section of skull and part of the right frontal lobe were removed. If the bullet had entered further back it would have hit the central brain and its blood vessels and most certainly have been fatal. We have repaired the missing skull bone with a lightweight metal plate, but he has lost brain mass on that side the size of a small orange. By that I mean a small American orange, approximately the size of a baseball.”

The surgeon then paused, shifting his weight and making his sensible, leather shoes creak.

“No one knows what effect this will have until he wakes up, if he wakes up. I must stress that it is an ‘if’. The shock alone of what Dr Kaplan has gone through would kill most healthy nineteen-year-olds. As well as the wound to his head, he took a bullet in his upper leg. There are also injuries to his chest, mainly from shrapnel, but these incredibly seem to have missed vital organs. Then there is the terrible burning. The burns along his left side and on his arms and hands are third degree and removed body fat, flesh and even the man’s fingerprints. His hair and moustache were burned off and many teeth knocked out, which we will replace, but making him impossible to identify, even if we had dental records, and there are bruises that show he may have undergone a severe beating. Imagine, if you will, a roasting chicken that jumps alive from the oven.”

The surgeon stopped speaking again, as if trying to understand what had happened.

“Dr Kaplan should not be here. He died several times on my operating table, but the angels do not want his soul yet. They must have a purpose for him.”

Kells just shook his head.

The surgeon smiled. “Yes, it is a miracle. And you witnessed his priapism, his erection. Usually present in men who have been executed. This man must have a strong life force. Will he walk again? It may be so if he survives the initial shock. Will he regain his looks? Up to a point. We have a captured female German plastic 12surgeon, a fan of GonewiththeWind, who rebuilds most male faces as versions of the film actor Clark Gable. This man deserves the very best.”

Kells nodded. “I thought you said Hyman here was going to die? For sure.”

There was a playful smile in the surgeon’s blue eyes. “It’s quite hard to kill certain people. If a man is very committed, say. And we had fun with this one. We did. We took risks, and here he is. Though he is still critical. He can go at any moment.”

Kells refused to want such a thing but who, exactly, had he saved?

“You think he’ll remember anything when he wakes up? When do you think he will come round? He cannot hear us, can he?”

The surgeon shrugged. He seemed to sense the colonel’s dilemma, though he had probably long since stopped trying to figure out such men and their wars.

“His heart may give out tonight. He may come around and start talking silkworms. It’s hard to say. You have worried enough, colonel. You’re going to come out of this very well. I heard they are flying you back to the States for your well-earned medal and promotion. You are a little famous, too. Don’t be modest! I think so!”

Kells reached into his uniform jacket pocket and gave the surgeon a card.

“Please call me at this number, day or night, when he wakes up. I would like to know. My boys will like to know. They like lucky stories.”

The surgeon was cautious, but moved, and raised his bushy eyebrows.

“That’s very thoughtful of you, young man. I meet so many young men who have become cynical. I’ll let you know the moment he wakes up. I am sure he’ll be eager to thank you himself. One small formality. There has been talk among the Jewish refugees of an ideal community, a kibbutz, literally a gathering, in Germany. I do not think Dr Kaplan may ever be well enough, but I would like 13you to sign him over to us, so we can send him there, should the opportunity arise. He is technically your prisoner and, of course, as a German will automatically have to go to a POW camp. That is harsh after what he has been through, and most ironic. If you could sign this release form, please.”

Kells hesitated and then signed with a pen his father had given him.

Kells stared at the man in the bed. There was something about this man that Kells was not at all sure of. He went to the side of the white-painted tubular steel military bed and drew close to the face. The breath came in and out with complete tranquillity. The terribly burned face, where it was not covered in bandages, seemed to glow.

Kells gripped the bed and sighed.

“There’s no point in worrying,” said the surgeon.

“Yes, I kinda figured that one,” said Kells. “There is nothing you can do about the odds.” Colonel Kells “Hollywood” William Bonney Vardy knew that for a fact.

The surgeon nodded. “You are young to be a colonel.”

Kells took a deep breath. “I was on the staff and the men above me kept getting killed. Men who knew what they were doing…” He heard his voice frantic on the radio. “Hollywood calling New York. Kansas hit a homer.” Kansas had been a major. New York was the colonel when Kells, Hollywood, had been a captain. Kansas had died from a stomach wound in a sewer by a river in Belgium. New York was luckier. An anti-tank round took off the top of his head when he stood up with cramp in his leg while giving a boring fly-fishing lesson with a drill stick he always carried. The blood had got into Kells’ eyes and his hair. He had washed and washed his hair, which was longer than it should have been, and he combed it in a quiff, but bits had still stuck together with the liquid remains of New York. Every time someone was messily killed, Kells was promoted.

“Did you volunteer?” asked the surgeon.

“Yeah, fool that I am, I volunteered for the paratroops, the 101st 14Airborne, because a sergeant had told me that jumping out of a plane was like surfing. I like surfing …”

In fact Kells had signed up first for an infantry unit and then changed to the 101st Airborne, the Screaming Eagles, to escape the endless latrine cleaning, petty power squabbles ‘chickenshit’ of the ordinary corporate military ant heap that makes you hate the army more than the enemy. But parachuting was not like surfing. It was freezing cold with the smell of vomit and urine, as grown men about to leap into the void were sick and peed their pants. The chute opened with a gallows jolt. You were meant to shout ‘Geronimo’, but everyone just said ‘Fuck it’. It was all right in the end, though. Kells dug the floating around by himself in the white clouds and the quiet … He did his harness straps up super-tight for his tall, thin frame. It made him feel he was ‘there’.

Even back home, Kells had only felt totally real when he was way out on his surf board and away from anyone else, looking for the big wave. He liked to be far out in the impossible surf he called ‘candy thunder’. As a kid, his tall, slender frame was always bang-bursting to climb a tree or look to the next ridge, or flying around the basketball court. He liked the joyous certainty of being driven by a strong wave to the shore, to a more materialistic American dream he tried hard to understand and, on most days, avoid.

“Why did you want to fight?” said the surgeon. Kells saw the man was sincere, and he needed to tell the affable Swede. No one had asked him the question before, probably because they did not want the answer. He did not want to fight anyone.

“Maybe I was stupid. I could have worked in my father’s armaments factory. I thought a tyrant like Hitler had to be stopped. By me, and that I would make the difference … All of a sudden everyone in my family and my girlfriend wanted me to go to war. They mostly thought of Hitler as the other team.”

The surgeon laughed.

“In Normandy I landed on a roof in the wrong town in the wrong part of that region and rounded up other twenty-something-year-olds 15as lost and angry and confused as I was after a third of our force had been slaughtered by well-placed enemy machine-guns and searchlights that no one had thought to mention. In the end, I had a whole company of men, so shocked to the core they were totally useless, and I sheep-dogged them to a large and beautiful church, which the allied barrages had only half-destroyed. I did not realise I had broken a bone in my foot. It was not until later that it dawned on me that my rebel action might have been viewed as mutiny and gotten me shot against a ruined wall. A captain was shot, charged with looting for passing out bread to his men from a levelled bakery. But a general heard of my ‘round-up’ and immediately attached me to his staff. It all seemed like a dream.”

Kells looked at the man in the bed. In the military it was hard to put a cigarette paper between triumph and disaster.

“So you have been with the general’s staff since the landings?” said the surgeon, concerned.

“Yeah, all the way to Berlin, but you begin to feel like outside it all.”

The burning man’s words, whispered in the priest’s ear, hissed like a snake in dry leaves.

“IchliebeSiealle.” I love you all.

Seeing awful stuff was not the worst thing, although he had walked through bloody fields of the newly dead and dying in squelching, oversize rubber boots, writing things on a clipboard in a shaky hand, making his reports. Wounded men cried out nonsense before they died. “I fucked whores in London town, then took my money back,” Kells remembered one man sobbing.

It was not that war was unknowable, an unapproachable horror, but that it was inaccessible to the framework of civilised ideas.

Worse than seeing and noting the detached heads and legs of the slaughter itself was the absence of any coda, as if the solidity of goodness had been reduced to wet tissue paper, and a moral tumble weed was blowing down a long flat road, from nowhere to nowhere. Kells did not know if he had killed anyone, personally. The fights he 16had been in were such complete chaos and quick and nothing like training. He had only fired his pistol on a few occasions. There was not time to notice the effect. And his brain seemed wired to forget the incident as soon as possible. To be truthful, he had never liked guns.

“It must have been terrible,” he heard the surgeon say.

“I am bad at talking about it.”

“Everyone is, in my experience,” said the doctor.

And all the time Kells felt he was not completely there. Not UP COUNTRY, not HOME, but NOWHERENOPLACE and not even that. He had thought actual occasional combat, such as his last mission in Berlin, might improve things, but it made him more removed. Floating among blurred and swirling pictures, like the distorted faces in a crowd he remembered from a French avant-garde film, even though at any moment he might be killed. He wanted to tell the nice Swedish surgeon that but couldn’t.

“I bet you have something to go home to,” said the doctor.

Kells nodded. “Oh, yeah. I hope to do a doctorate on Dante’s La Vita Nuova … The New Life …”

The Swede shook his head. “I was meaning, is some girl waiting for you?”

Kells smiled and nodded, embarrassed. “Sure. She’s called Betty. A former Miss Palo Verdes …”

He pictured Betty eating a strawberry sundae with marshmallows, a dab of ice cream on her lower lip as her breasts hung over the table imprisoned in a prim cotton dress. Her father was a senior manager in his father’s factory, and Betty was the girl next door but two, who had left school at fourteen and was already planning where she and Kells were going to live. She was disturbingly clever and had always added up store bills in her head before the manager had got his pencil out.

Kells’ mental energy was aimed at trying to grasp the whole show, the universe, the reason we are here and how to save mankind, while Betty liked sloppy romantic movies and a few pert kisses at the drive-in, but no gift of tongues or wandering hands. He had 17known her since fourth grade and watched her grow into a voluptuous siren with long dark hair who caused traffic accidents in her short, short, cheerleader ra-ra skirt and Bobby socks. Everyone said Kells was a lucky man. But her strict father forbade Betty to go to surfing beaches or parties. So Kells went on his own. He did not feel he was cheating on Betty because she represented HOME to him. The same HOME the army promised you for surviving the war and them.

Betty had found him reading Dante’s LaVitaNuovaand he had tried to convey to her how Courtly Love could be sublimated to the divine and change the world and stop all war. How Courtly Love was an experience between erotic desire and spiritual attainment, a love at once illicit and morally elevating, passionate and disciplined, humiliating and exalting, human and transcendent. He was about to add, taking her small, hot hand, that he thought sexual love might be elevated in the same way … Kells had never even gotten inside her brassiere – to change the world and bring peace on earth.

Betty had looked up at him with startled blue eyes. “Courtly Love? If folks get sent to court for what they get up to when out courting, it must be completely disgusting. Please don’t say such stuff at our house. Is that what you’ll be learning at your new university?”

He had not been sure if she was joking. At times she pretended not to understand him to retain control. She still used the word “courting” for going steady. She was adored by his mother and father.

“What news from Billy the Kid?” wrote his dad. Kells had toy guns before he could walk and was brought up on cowboy movies. Yet his mother had dressed him in her shorty nighties when he was young. She had lost a little girl two years before he was born. His mother had named him after the Irish national treasure, the Book of Kells. Among the spiral of images in Kells’ brain, the burning man had begun to move him. To have weight and meaning. Like Dante. He was real and not a dream.

“Am I still your dreamboat?” Betty used to ask after he had been surfing.18

“Goodbye, colonel and I hope you see Betty,” said the Swedish surgeon, called away by a nurse.

Kells was miles away. “MachtNichts” he said, mostly to himself. Literally it meant “that makes nothing”. It was a thing all the guys said. It doesn’t matter. None of it … The war … The whole fucking meaningless slaughterhouse … That’s why Hyman here, the burning man, mattered a lot.

The surgeon looked at Kells curiously and left.

IV

The man in the bed, the burning man, the international hero, woke the next day with an intense pain in the middle of his brow. It hurt very much indeed when he tried to open his eyes. For a moment, he was afraid and grabbed at the sheets, but that only increased the thundering headache. He fell back, exhausted. One eye opened. He was in a green room that smelt of cleaning fluids. The sunlight was streaming in through a window and dancing on the walls in wavy patterns, possibly reflected off water outside.

He blinked his right eye. He could not see out of his left eye, which was now covered in bandages.

The window was slightly open and there were scents of spring, above the smell of bleach and polish. Through the window was a cherry tree covered in light pink blossom and beyond the blossom was blue sky. He attempted to turn his head but could not. There was a saline drip by the bed. On a hanger hooked on a white wardrobe at the other end of the room was a brown coat on which there was a yellow star. Was this garment his? This made no sense to him.

A piano was playing somewhere outside the window. He tried to remember what the music was but could not. He could not remember anything. He did not know who he was. The question seemed to stick in his dry throat in panic. He stared out at the cherry blossom and the intensity of his thought blurred and he passed back 19into image free unconsciousness. His head was not yet ready for dreams.

Three days later the man woke again in Isolation Room Six. Outside the window, probably under the cherry tree, a military band was playing modern American jazz.

The music stopped and an American voice shouted “Pennsylvania 65000!” and then the music started again.

It made the man now known as Hyman Kaplan want to smile and get up and dance, which was a joke. He was still not able to see out of his left eye and knew he was terribly wounded and at times felt he was on fire. Despite the drugs, he was in pain. There were bubbles of respite but then the pain came back and its absence was almost worse than the agony.

Yet he wanted to dance.

Had he liked to dance? The nurses, the older nurse and a younger girl, were looking out of the window and then began to dance themselves. Their big white shoes clattered on the wooden floor.

He must be careful, he knew.

He was in a hospital, but it may be the hospital of his enemy. They may be making him better only to torture and interrogate him again before killing him. He knew that was the way of things. The man did not understand all of the English, but they were talking of a dance called the Jive. It was an exciting dance where the partner was whirled around. The girl was laughing.

“That’s it, Rachel. You got it, first time,” said the older nurse.

Rachel was beautiful and so innocent. She stopped dancing and came over to the bed. He firmly shut his eye.

“The Swedish doctor said we should talk to him.”

“Don’t waste your breath, Rachel. He’s deep-six, in a coma.”

But he felt the girl’s warmth as she came and leant over the bed and whispered in his ear, “DerChirurgsagt,SieseienDr.HymanKaplanundeinExpertefürSeidenraupen. The surgeon says you are Dr Hyman Kaplan and an expert on silkworms.”20

Her whisper was so close it tickled and sent a shiver through him. So he was German … Was he the enemy? He did not know the name Hyman Kaplan … Silkworms! They sounded like a contradiction or a pestilence. Surely he would remember? They meant nothing to him and he did not even know what a silkworm looked like. He did not care. Rachel smelt of roses and hope.

She was smiling now and “jiving” again with the older nurse at the end of the white tubular steel bed. He opened his good eye enough to see them. He knew one thing: if he did not die, he wanted Rachel. However impossible that was.

Whoever he was, he meant to have Rachel.

“Pennsylvania 65000!”

V

An hour later, Rachel was one of two nurses who went into the room to change the saline drip of the resistance fighter the American colonel had rescued. “You change his drip this time, dear,” said the older nurse. She was American and very experienced.

While she was attaching a new bag of saline solution, Rachel saw a flickering of his eyelid.

“He’s awake! He’s awake!”

The older nurse looked at the patient. There was a flicker of the right eye, and then nothing.

“Shall I go and get the surgeon?” Rachel said, excited and so happy. “Surely this is a good sign?”

The older nurse held onto Rachel’s arm gently. “Don’t get your hopes up too much, honey. Even when they start to pass in and out, cases like this. The next day or two will tell. All I am saying is do not get too fond of him. You must know that better than I can tell you, poor child.”

Rachel, who was only twenty, was adamant the burning man was going to live. She had pinned back her red-gold hair under a white cap. She was so very happy she was able to help Dr Hyman Kaplan. 21He was a hero. He was her hero. She pressed her lips together in determination.

The Russian soldiers had opened the doors of her prison camp weeks ago and let her free, with a group of other specifically political prisoners. Now Rachel found herself here, in this hospital, in charge of a man who had fought, really fought, and the Nazis could not kill. He was going to be so pleased when he realised he had woken to a new world. Dr Kaplan was going to live. No one knew how much she depended on that.

She finished securing the drip when the slightly fat and untidy middle-aged rabbi who was in charge of the group from the camps, came into the room. He had little round glasses and was so gentle. His grey hair curled at the sides and back of his bald head. He too had been in the resistance. Yet, he made every room he entered happy, a trick she knew might not tell his whole story. She had broken down and run out of the hospital the first time she tried to talk to him.

“Ah, Rachel, you are looking better, child, but you must eat more. Forty kilos is not enough at only twenty. Ah, to be that age again! I must give you some of my kilos from too much rum. You were going to tell me what happened after you left the camps last time, when you were called away.

Rachel took a deep breath, cleared her throat, smoothed down her dress and began. She was conscious that she made everything into more of a story than it was. “… When we left the camp we walked for several days. The Russian soldiers with us ran off with the food on the fourth day. Then in an abandoned suitcase I found no food, only a few lipsticks and feather boa scarves.

“Lipstick in the camp was only worn by those who became the doomed girls of the officers. I passed out the suitcase’s contents. Then there was a miracle. Most of us were giggling, though others were crying, as we put the lipstick on, reds and pinks and one almost white. Even several of the boys joined in. I chose a pink lipstick. It tasted of Turkish Delight. I then put on a yellow feather boa. 22Another girl put on one of deep blue and began to dance. We were women again.

“I felt like a film star. We had stopped, dazed, by a clump of trees, when three trucks came into view around a bend.

“‘It’s the Yanks,’ said one of the boys, as they all saw the uniforms and the white stars on the lorries. It was getting dark and there was the smell of honeysuckle in the air.

“‘My God, look at this,’ said a woman doctor. Then they brought us here, to you. It was the start of the world again. The future.”

Rachel was silent for a while, looking down at her white shoes. When the Americans told them to get in the trucks, she realised the girl she had been walking with lay dead by the side of the road, her muddy eyes wide open. The rabbi got up and got her a glass of water; she took a sip.

“I know this is hard, my dear. I remember seeing you the first time those doctors who found you brought you here. You said meeting a rabbi was like a distant memory … Can you tell me about your family? Were you arrested?

She put the glass by her chair. After telling the lipstick story it strangely became easier.

“We were not so religious … I was the daughter of a prominent doctor in Berlin who specialised in treating artists and actors. He was blond-haired and I looked more like one of the Nazi poster girls than Jewish. My father was denounced by a man who promised the world and then stole morphine from the surgery, which should not have been there and had been used to help my father’s fashionable patients, who had connections with, or were lovers of, Nazi Party members. The very people who eventually arrested him …”

When she thought of her childhood, she always heard herself playing the cello, a sad, low sound that pulled at her soul with an exquisite melancholy she only now understood. A melancholy and a memory that was not straightforward, like many things she recalled and did not entirely trust. 23

Her uncle, who was a musician, an accomplished cellist, had taught her to play.

“My kind, funny father, kept thinking the Nazis would be swept out of power as they had swept in. Probably as a reaction to his optimism, I became involved in smuggling Jewish activists and communists out of the Reich in Red Cross ambulances. These were meant to meet wounded soldiers off the ancient, dirty clanking steam trains that smelt of damp wood coming from the Russian Front, that arrived at night into quiet stations outside big cities like Berlin, where they disgorged the blinded, and the maimed. I met a boy at the music conservatoire who hardly needed to convince me to help. I pretended to be a nurse, and it was like being in a school play. I did it several times and it all seemed so easy.

“One day we drove around a bend in a forest and there was a roadblock ahead. The driver tried to turn the ambulance round, stalled, and was shot in the head … There was blood … I got out of the door and tried to climb up the bank …”

She could still smell the rich forest earth as she had clutched at tree roots to get away.

“But a soldier grabbed me by the coat and then by the hair and another hit me in the face with his rifle butt. I was thrown into the ditch with the others and the soldier who had grabbed me shot one of the smuggled men in the face and laughed … I was screaming, screaming, screaming …”

Rachel was breathing heavily. “Take your time, my dear,” said the rabbi.

She composed herself, the fear snapping at her like the soldiers’ dogs.

“I was kept from the others in a little, freezing cell with a stone slab for a bed and a chair bolted to the floor. After three days a female warder came in with a tape measure.

“The warder said, ‘Today, Rachel, you will go to the guillotine for what you have done and that you are Jewish. We have a travelling version in the van. It has been used successfully on those terrorist 24students in the Weiße Rose dissident organisation. Are you one of them? Come on now, stand up. We must get your measurements exactly right so the blade cuts cleanly through your pretty neck. It will soon be over. The less you fight and the more you obey the easier it will be. It is in the best interests of the Reich.’”

Rachel had wet herself.

She had heard her urine drip-dripping from the wooden chair and the warder had laughed.

“My hands and feet were put in shackles and I expected to be taken to die immediately. I was trembling and crying. But they took me in front of a panel who were silent for a long time. Two men and a woman. Very ordinary and in civilian dress. The woman had a pearl hat-pin and a fox-fur stole. They did not beat me, or shout, but I was quietly questioned and questioned for days by them and by night by guards, without sleep.

“You must tell us your contacts … Admit you are a communist … How long have you been a party member…?

“I only knew those I had been arrested with…

“But they went on and on until I felt I was being separated from my soul. That there was nothing left. A husk.

“Then they stopped…

“I thought it was the end. That the guillotine was in the next room. From time to time I heard loud, mechanical sounds and then nothing.

“But I was taken back to my cell and the next day I was summoned by a different group of three men in army uniform. I told them I was a nurse and they were pleased, and even polite. They must have already decided I was of no resistance importance, and I kept myself hunched and most of my hair under a scarf.

“I was sent a long way in a van to a camp in a forest. There was an infirmary where a doctor and several nurses brought the torture victims back to a sort of a life, before they were tortured again. I made myself invaluable as a nurse, even working in the operating theatre, re-setting freshly broken bones. They liked me too because 25I could speak German and French and English as well as some Russian and Italian. A pretty girl I was working with was taken to the officers’ quarters. The girls were often sent to the officers’ quarters and then, when the officers tired of them, to another camp where no one came back from, so I made myself plain.”

She did not sleep for fear of nightmares.

One day she had heard the sound of a voice behind her. It was the surgeon commandant.

“What fine ankles you have, my dear.”

She had shuddered and pulled her scarf closer to her head. She felt his breath on her neck.

His voice was soft and he was kind to her. Very kind. He gave her cake he made himself. He did not give her orders. It was confusing. He had been wounded in the legs in Russia. His name was Manfred. Rachel did not tell the rabbi about Manfred.

Here, in the American hospital she looked out as the blossoms fell from the cherry tree.

“Thank you,” said the rabbi. “You are very brave.” But she wasn’t. If they only knew what she had done. The rabbi then put a hand on her shoulder.

“There is what we call a kibbutz, not too far from here, in the grounds of what was a leading Nazi’s house. It is an ideal farming community. Everyone works the land and then has time to pursue their own specialities. No one is in charge. Everyone is in charge. Women are equal to men. Such communities existed in the early days of the Reich and were championed by certain Nazis as a way of getting we Jews to emigrate. It is a rehearsal for the kind of settlements that may be established if the Jews return to Palestine and would lay the foundations for a new Israel, though not in an old-fashioned imperialist sense. Or even as a state. We will take no one’s land and everyone is free to join our communities.”

The words filled Rachel with joy. She collected herself, sat up straight, and tried to smile. The people she had escaped with were all activists who hoped to establish a new way of living where there 26would be no more war. But she said, “I cannot leave my patient …”

The rabbi nodded and left and she looked over at the man in the bed. Again, she thought she saw an eyelid move.

VI

A week later, the older nurse was teasing Rachel about the handsome American, Colonel Kells Vardy.

“He took you to dinner. He’s interested in you …”

The colonel seemed a good man. He had insisted they go out for dinner. There was a PX store attached to the hospital and a restaurant there. The older nurse had encouraged her, but she should not have gone. It was all too soon. He had been very charming and polite, but she had rushed to the bathroom and thrown up. She then told another nurse to tell him she had forgotten to change a patient’s bed sheets back on the ward, perhaps they could make it another time.

Rachel found it hard to imagine such a man, a boy, in a war at all. “That’s the sort of young man who always gets rewarded. And he’s after you. He wants to have fun. You could have a bit of fun too.”

Rachel thought the American much better off without a person like her.

She must devote herself to the patient Hyman. She had to.

She heard the sound of American jazz coming from somewhere below in the building. They were having a party. The Americans always had parties.

Rachel had several books with her. She was learning Hebrew and she had found the works of the English poet T. S. Eliot, translated into German, which she read out loud. In the prison camp hospital when patients had been almost bludgeoned to death and were in a coma, reciting poetry to them, she believed, helped heal. She had recited Schiller and, when no one was listening, the forbidden Rilke. But it did not change the patients’ eventual fate.

The eye of her patient opened and closed again.

Ten minutes later this happened once more.27

On the next occasion, part of the way through a poem about a cat who was not there, the eye snapped open for over a minute. It was such a strong gaze in the direction of the cherry tree. She went immediately to get the older nurse, who went to get the surgeon. When they returned, the eye was firmly closed.

There were several false alarms like this over the coming days. The surgeon said that Rachel should sit by the patient full time. Rachel liked reading to Dr Kaplan. It made her feel safe.

Her father always said she had a calm and melodious voice and one morning started with a Chekhov short story, translated into German, called ABoringStory, which was anything but, about a silly university professor, anticipating his death, trying to right wrongs. The professor, it turned out, was not a stupid man after all; a little vain, perhaps. She bit her lip. Maybe she should not have read the patient that particular story as it involved death. She gave Hyman’s hand a little squeeze and she thought she detected a murmur of pleasure as she wiped the saliva from his mouth. All the time Rachel listened to the breathing of Dr Kaplan, which she was convinced was growing stronger. When she paused, she saw Dr Kaplan’s eyelid quiver.

There was a knock at the door and a man she had seen with the rabbi came in. He was carrying a book, in German, which he handed to her and left. It was about the silkworm, Dieseidenraupe. On the front of the book was a picture of a smiling blonde-haired woman, not unlike herself, holding a little cocoon of silk. The book was entitled: DerkostbareFaden, The Precious Thread, and had been brought out in the early days of the Reich. She read:

“The process starts with the eggs hatching out on the mulberry leaves in a sericulture centre. The caterpillars eat their own homes they are so greedy and spin a cocoon of silk around themselves. They are in their finest outfits. All their greediness has clothed them in the best fashions. Then, before they can breed, and pass on any racial flaw, they are exterminated. This is done by steaming them over cauldrons of boiling water for hours and then they are right 28for spinning. Many thousands can be killed in a day in a modern centre, millions in a year. All to make the finest gowns or parachute silk for our airmen.”

Rachel trembled and put the book down, in tears.