Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

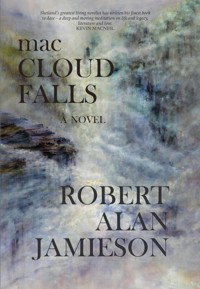

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In the summer of 2011, Gilbert Johnson, an Edinburgh antiquarian bookseller suffering from cancer who has only ever travelled via books before, decides to make one big journey while he is still fit enough – to British Columbia on the trail of an early settler he believes may have been his runaway grandfather, a man who went on to become important in the embryonic 'Indian Rights' movement of the 20th century. Flying over the Rocky Mountains he meets a fellow passenger, a Canadian woman, so beginning a relationship that ultimately carries the two of them deep into the interior of the province. macCLOUD FALLS is both an exploration of the Scottish colonisation of B.C., and a roadtrip romance full of humour, rich characters and incident in the shadow of impending death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 692

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

By the same author:

Soor Hearts, Paul Harris Publishing, 1984

Thin Wealth: A Novel from an Oil Decade, Polygon, 1986

Shoormal, Polygon, 1986

A Day at the Office, Polygon, 1991

Ansin T’Sjaetlin: Some Responses to the Language Question,Samisdat, 2005

Nort Atlantik Drift: Poyims Ati’ Shaetlin, Luath Press, 2007

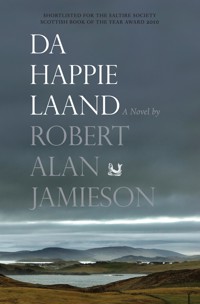

Da Happie Laand, Luath Press, 2010

First published 2017

ISBN: 978-1-912147-07-6

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by TJ International, Padstow.

Typeset in 10 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Robert Alan Jamieson 2017

The historical core of this novel is based on the life of James Alexander Teit (1864-1922). The remainder is fiction.

This book is dedicated to the memory of three dear friends who passed away during its writing: Gavin Wallace, my old co-editor on the Edinburgh Review, whose encouragement and enthusiasm for the idea was invaluable at the outset; Richard McNeil Browne of Main Point Books, a friend of almost thirty years, whose kindness, wit and wisdom I greatly miss; and finally, Isaac, the King of Shelties, finest of canine companions, the true ‘Hero’ of this tale.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Creative Scotland for a major bursary that allowed me to make nine visits to British Columbia during the writing of this book; to the University of Edinburgh for its continued indulgence and support; to my friends at Luath Press, Jennie Renton and Gavin MacDougall, for continuing to make publishing both pleasurable and easy; to staff at the BC Archives, Simon Fraser University, University of British Columbia, Vancouver Public Library, Nicola Valley Museum and Archives, and Kamloops Museum and Archives for their assistance; to Karen Dawson for making it possible to spend two memorable months writing in Italy, and Patrick Jamieson for his companionship then; to my neighbour Barry Smith for the Ryga book; to the many friends in Canada who contributed good times, knowledge and sometimes accommodation, especially Adam Pearson, Byron and Sheila Anderson, Michael Elcock and Marilyn Bowering.

Most of all, thanks are due to the Vancouver poet, Miranda Pearson, who appeared as if by magic in the skies over Scotland in 2010 and helped to seed the idea, who has remained magical ever since.

DANCE PROGRAMME

1 – Oldest Inn in ‘New Caledonia’ (Boston Two-Step)

2 – The Walking Scotchman (Slow Waltz)

3 – Country & Western Capital of Canada (Square Dance)

4 – The Road to Happy Ever After (Quadrille)

5 – The Best of Seven (Finale)

First Dance

Oldest Inn in ‘New Caledonia’

(Boston Two-step)

SHE THREADED HER fingers through the worn metal handle, put her thumb on the old-fashioned latch and a little bell rang above her head as the door rattled open. ‘Come on lad,’ she said to her dog. After the dazzling sunshine she’d left outside, her eyes took a moment to adjust. It was certainly quaint inside, like something out of a movie, maybe some old spaghetti western. Gil had said it was built in the Mexican style. The arch that welcomed them into the foyer had a low adobe curve, and the whole place seemed made of terracotta.

‘Are you the innkeeper?’ she asked of the only person visible, a figure crouched at the desk across the hall who sat up as if he’d been dozing. The question hung in the hazy violet light that framed the speaker, the tall brunette woman in a deep purple dress who had entered with a dog at her heel. It was one of the Lassie breed.

‘Can’t say I’ve ever been called that before,’ he answered in a voice from the east. In a second, it seemed she crossed the foyer in long strides and stood above him. He looked up, was caught by her intense brown-eyed gaze, still half-asleep.

‘But this is the inn, isn’t it?’ Her tone was impatient, dismissive, her accent foreign somehow.

‘Sure. The oldest inn in the province, though I guess it’s more of a motel these days. Back then, they had no mo, y’know.’ He smiled, as if the line was well-rehearsed, awaiting a response.

She stared down at where he sat, gently oozing sweat despite his being dressed in thin grey t-shirt and khaki shorts, and the fan spinning with a periodic squeak above his head. ‘I don’t understand?’

‘No motors. No autos. Back when they named it the inn.’ If it was intended as a joke, she wasn’t amused. The dog circled her heels and sat down, facing up at him, its expression as blankly insistent as the woman’s.

‘You have a Scotsman staying with you?’ she asked.

He stood up from his stool behind the desk, a small slight fella, hardly as tall as her shoulder. He hesitated as if weighing her enquiry, then nodded. ‘Sure. Mr. Johnson.’

Her tone remained urgent. ‘Can I see him?’

The innkeeper shook head. ‘He’s out right now.’

‘Is he okay?’

‘I think so, yes. Why?’

At that, she gave out a deep sigh. ‘Thank God,’ she said softly, and bent to pet the eager dog. ‘We’ve been so worried about him, haven’t we, lad?’

‘Why?’ the voice asked again.

She stood up and gave him the once-over, before adding. ‘I think he may be planning to kill himself.’ She spoke quite matter-of-factly and the innkeeper didn’t appear too shocked at first, but as the meaning of her words struck him, he gave a little gasp.

‘And what makes you say that?’ he asked slowly, as if trying to gauge her sanity.

The tall dark woman gazed around her, seeking for some inspiration as to how to turn her feelings into words. ‘Well, it’s hard to explain. He sent me a postcard the day he got here, a picture of the river. It said ‘Sometimes I take a great notion.’ And he was reading a book about a Scotsman who travelled into the north of Canada to die.’

The innkeeper scratched his head behind his ear. ‘I don’t really get what you’re saying.’

She stared down at him. ‘In Vancouver. Or rather, when I met him on the plane. About ten days ago.’

The innkeeper smiled again, shook his head. ‘Nah, you’re gonna have to explain. Sometimes I take a great notion to what?’

‘We were walking down at Jericho Beach, you know in Vancouver. We passed a bench, and you know how they have these little plaques? Well this one said ‘I’ll see you in my dreams’ and Gil, your Mr Johnson, sang ‘Goodnight Irene.’ I asked what it was and he said it was a song his mother loved. And he sang that line to me. Sometimes I take a great notion, to jump in the river and die.’

‘Goodnight Irene,’ the innkeeper said. ‘Sure. I know it. But it’s just a song. Doesn’t really mean he wants to jump in the river, does it?’

Not dissuaded, she carried on. ‘But the book he was reading, Sick Heart River – he told me, that’s exactly what the Scotsman in that book wants – to die. It’s why he comes to Canada.’

‘Sick Heart River?’

‘That’s what the book’s called.’ For a second the two stared at each other, as the dog looked from one to the other, unsure what was passing between them.

‘Okay,’ the innkeeper said. ‘Maybe could you go back to the beginning, please? I’m kinda confused.’

‘The beginning? Well, I met him on a plane from Calgary… last week. I mean, I got on at Calgary, but he was travelling from Scotland. We got talking and when he was in Vancouver – before he came up here – we hung out a bit.’

He stood a while, gauging her, as if unsure what to say next. ‘So you’ve come all the way up here from Vancouver because of this.’

‘I couldn’t get in touch with him, I sent messages, texts, but...’

He laughed at that, and came out from behind the desk, his arms splayed and his palms upraised. ‘We’re off-radar, is all. None of that works here in the canyon. So he won’t have got your messages, is all.’

‘But I tried to phone here and it just rang and rang and nobody answered.’

‘Ah,’ the innkeeper said. ‘Well, you know, I’m on my own here right now. Since my wife left. And sometimes I have to go out.’

She stared at him for a few seconds, as his words took meaningful shape in her mind. When she spoke, it was only to say with some incredulity, ‘We drove up. Six hours.’

‘We?’

She indicated the dog.

‘Must be good to have a dog to split the driving with,’ he said, but again she wouldn’t laugh. ‘Listen, you look like you could use a strong drink, and maybe your dog would like some cold water? It’s pretty hot up here right now. Come out onto the terrace and into the shade, and tell me why you’ve driven six hours to get here, why you think our Mr Johnson may be planning on killing himself. Cause the reasons you’ve given me so far don’t seem like good ones.’

She studied his face for a moment. ‘Well maybe a cup of mint tea would be welcome.’

‘How about ordinary tea?’

‘Okay.’

He led her through the empty dining room, out onto a terrace overlooking the river. She sat in the shade at an ironwork table, with the lassie dog at her feet, while he boiled a kettle behind the little bar. ‘And that is quite a river, like Gil said,’ she breathed, patting the dog while gazing over the bank that led down to the vast urgent flow of flinty grey water racing down through the canyon. The high rocky face opposite was mostly in shadow, but the very top of the crags caught the last of the setting sun.

‘Sick Heart River,’ he said, when he returned. ‘You know, I think my wife may have read that. Title seems familiar.’

‘I don’t know much about it,’ she answered. ‘Just what Gil... Mr Johnson told me. It’s by some Scotsman who was an early Governor General.’

He put a tray with a small blue teapot and cup on the table, then sat down opposite her. ‘So tell me, why do you think he would he want to kill himself? I thought he was a writer, here to research a story.’

‘He’s not a writer,’ she said. ‘He’s an antiquarian bookseller. He told me he’d always wanted to write, but never had.’

Again, the innkeeper looked non-plussed. ‘So he sent you a postcard, so he’s a reading a book about someone dying, you couldn’t get a reply to your messages, you panicked a bit. I can understand all that. But that’s no reason to drive up here, surely?’

She sipped her tea. ‘No, there’s more. His mother just died. And there’s the cancer.’

‘What cancer?’

‘Didn’t I say?’

‘No.’

‘He’s got cancer. He told me on the plane, how he wants to make one big journey before he dies.’

The innkeeper’s expression had changed at the dread word. ‘Here?’

She nodded. ‘I guess so.’

‘Hmmm.’ He took a sip of his tea and stared out across the river towards the little town on the other side. ‘So, you met a guy on a plane a couple of weeks ago who told you he had cancer, who was talking about death, suicide. Then he sends you postcard with a cryptic note on it about jumping in the river and dying. You can’t get a reply to the messages you send?’

‘It’s more than that. I had this really strong feeling. Like a premonition or something, you know?’

The innkeeper sat silently studying her for a while. Then he said quietly, ‘Sounds a little crazy,’ as much to himself as to her.

The word made her flinch. ‘You think so?’ she asked, an edge of annoyance in her voice. ‘It happens, you know.’

He shrugged. ‘Well, no, I don’t know. But I’m a little worried too now.’

‘It’s such a strong sense that something’s wrong.’ She looked at her watch. ‘It’s getting late. Where could he be, do you think? Isn’t there someone you could call?’

‘Just hang on. Let me think a moment.’ They sat in silence for a while, the dog panting at her feet. The innkeeper, as she’d called him, stared out across the river. His gaze was focused, as if checking all the houses and buildings he could see, eliminating one by one the places where the Scotsman couldn’t be. Then he went inside to phone while she stayed on the shady terrace, sheltered from the baking sun. She could hear his voice in the distance asking questions of whoever was on the other end of the line.

She stood up and leant against the wall of the veranda, so she could see the little town in the canyon properly. It was desert alright, like Gil had said it was - the end of that arid belt that stretches north from Mexico through the US into western Canada. She ran her eyes over the town across the great river and counted maybe fifty houses at most. Surely he couldn’t be too lost in such a small place? But no, she had a bad feeling she couldn’t explain away.

‘Sorry,’ the innkeeper said as he reappeared in the doorway, his flip-flops slapping the tiles. ‘I called around the likely places. Nobody’s seen him today.’

Call it intuition, whatever, she wasn’t surprised. ‘Something’s happened. I know it has. We should call the police.’

‘Mounties to the rescue?’ he smiled. ‘No, there could be any number of explanations. Besides, why would he want to harm himself when he’s so busy with this research? He’s been meeting a lot of people since he got here, he could easily be in someone’s house. You know, interviewing somebody.’

She sighed deeply and the dog looked up, as if recognising the sound and what it indicated. The innkeeper watched as she sat upright, brown hair falling around her face. She was very striking, and somehow familiar, so much so he seemed to know her face from somewhere. Was she an actress or something?

‘I don’t know. Can I see his room?’ she said suddenly, quite firmly. ‘He may have left a note.’

The innkeeper was so captivated by her resemblance to someone he couldn’t quite recall, he was about to consent, but then he hesitated. ‘Now, I don’t think I can do that. It wouldn’t be right. I can see you’re worried, but really…’

She interrupted. ‘You have a pass key?’

‘Sure, but…’

‘You enter his room each day to fix it?’

‘Sure, at least the maid does.’

‘I only want to look around.’

‘Well, I don’t know, I mean you just turn up here, you could be anybody. I don’t know you, though I feel as if I should.’ He hesitated again. ‘Are you someone famous, on TV or something?’

‘I’m here because I care. That’s all you need to know.’

So, perhaps just to pacify her, he relented and led her up the narrow winding staircase to a door marked with a 14. The dog was at her heel all the way, panting with the heat but always no more than a step behind her.

‘This is it,’ he said, and opened the door with his pass key. Inside, a video camera on a tripod pointed out the window across the river towards the houses on the far bank, and a long desk under the window was stacked with books, some open at a particular spot. It looked like a scholar’s den, even though he’d only been there a few days.

‘I don’t understand. Where did he get all these?’ she asked.

‘Ah. Now that I can explain. He went through my wife’s library the other day. She hasn’t taken her things away yet so I told him he was welcome to borrow whatever was useful.’

She and the dog moved forward as one, and she began to read the titles on the spines. Indian Myths and Legends from the North Pacific Coast of America, The Thompson Indians of British Columbia, Our Tellings, Skookum Wawa, and another twenty or so piled high.

‘Mostly he’s interested in the history of the province,’ the innkeeper observed. ‘I guess it all relates to this guy he’s…’

‘Lyle?’

‘Yes. James Lyle.’

Hidden behind the stack of books, they saw his laptop, lid down and switched off. It would be passworded, no doubt.

‘Well, no suicide note that I can see,’ the innkeeper said with a smile. She didn’t answer, but moved elegantly forward with slow steps, her brown eyes searching the room. The bed was neatly made, his clothes all hung up, with the exception of a couple of shirts and a pair of shorts lying across an armchair. She went to the bedside cabinet and pulled the drawer open. Nothing but tourist brochures.

‘Maybe we shouldn’t…’ the innkeeper began, but she silenced him with a glance. ‘What’s that?’

She flicked, eyes seeking content, through a few pages of a notebook on the desk. ‘His writing, it seems.’ As she stood scanning the pages, the innkeeper moved nervously around her, while the dog stood still, watching him with its dark eyes.

‘What if he comes back and finds us here?’ he said.

‘I’ll take responsibility,’ she said imperiously, and took a pair of expensive-looking pink-rimmed glasses from her purse. ‘It seems to be a diary,’ she added.

From outside, the sound of a fire-door opening echoed up the stairs. ‘Put it back,’ he said anxiously, but then relaxed when he heard voices. ‘Ah it’s only the tree-planters coming in. I could ask them if they’ve seen him.’

‘The tree-planters?’

‘They’re working up north, stayin here. Mr Johnson is quite friendly with them.’

She didn’t answer, but turned another page in the large notebook. The innkeeper’s reservations seemed to have evaporated. ‘Look at the end,’ he suggested. ‘The last thing he wrote.’

She thought for moment and then, as if deciding that was good advice, she flicked forward through the handwritten pages, until she came to an unfinished one.

‘It says “Today, the sacred valley”,’ she said. ‘Where’s the sacred valley?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Isn’t it somewhere round here?’

‘If it is, I never heard of it. But we only moved here three years ago. My wife might know, though. She’s very interested in all that local history stuff.’

‘Could you call her?’

‘I guess. Though we don’t talk much anymore.’ He pointed to the journal in her hands. ‘Maybe if you read farther back a bit, it’ll tell you what he means?’

‘I will.’ Her eyes were taking a ranging view of Gil’s writing. ‘You go ask around – see if anybody knows where this sacred valley is.’

Again he hesitated, still unsure of whether he was doing the right thing in helping her root around in his guest’s room. Then it struck him. ‘Sigourney Weaver! That’s who it is,’ he exclaimed. She looked up at him over the rim of her spectacles and smiled, then shook her head, as if she’d heard the same idea endlessly repeated.

‘Don’t… please,’ she said.

‘But you’re not… not really?’ he asked, confused.

‘Oh, just go already, will you!’ she commanded. The dog had been watching her every movement and lay down at her feet, panting with the heat, as if scolded. The innkeeper began to apologise to her, still seemingly uncertain as to the woman’s true identity, but she shooed him out the door.

Once he’d left, the woman who was tired of looking like Sigourney turned her attentions to her dog and said, ‘Poor boy, it’s way too hot for you here.’ She sat on the end of the bed. He jumped up beside her and she patting him lovingly with one hand as she flicked back through the pages from the last entry in the missing man’s journal. ‘Let’s see if we can find another mention of this sacred valley,’ she said, perhaps to herself, perhaps to the dog, as she scanned the pages in reverse, making her way back towards the beginning. It seemed to be a record of his movements here in Cloud Falls – but it was written in the third person for some reason. No other mention of this valley caught her eye.

Instead, she began to read the first page.

Coincidence is – perhaps – a symptom of fate. Perhaps, because it arises per hap: through chance. Imagine: you have spent a summer sitting in the garden of the place you are living in, watching planes fly low overhead as they approach the nearby airport. You have watched them knowing that you may never fly again, because you are being treated for cancer by radiotherapy. Your throat is a dried-up wrinkling, red-hot on the inside, red-skinned on the outside. You have no energy, no enthusiasm for an active life, except to watch – you watch the swifts and the swallows as they zip and flit above the river, feeding among the floating specks of insects lit up by the setting sun. Your view is to the west, the end of day, the end of life. But by the time that the first leaves are yellowing, you find yourself on an aeroplane, leaving that airport, flying above your riverbank retreat towards a place you have never been. Yet somehow you are returning to source, swimming upstream. Your seat is in the last row, at the rear of the cabin – you do not greet each other. She is intent on reading, and so are you. After half an hour, you are flying somewhere over the mountains, heading west, when the voice from the cockpit announces a problem with one of the engines, and so the plane will make a forced landing at another airport. You glance at your fellow traveller, the invisible wall of separate concentrations suddenly melted away. There is a look of panic in her eyes – her very dark brown eyes. But as the sun catches her face, a flash of gold among the brown surprises you. There is light and terror in her look, a glancing fear that sparks your interest. But you do not speak. Instead, you gaze down at the mountains and valleys below. A lake, a river, a snaking sliver that cuts the landscape.

From up here, life is tiny. Your life is tiny. And you have thought about that, sitting in the garden of the riverbank cottage, watching the planes. How tiny your life is, and how short it has been. Cancer sharpens awareness, even as it clogs the body with unwanted, non-functioning cells. In the past few months, you have come to terms with death, have put your affairs in order, said goodbyes. If this plane crashes, and you die, it could not happen at a more opportune moment. Thanks to the cancer, all is ready. But she looks as if she has life ahead of her, things she must do, and places she must go. People to see, perhaps children to care for, a husband.

The plane circles above the metropolis, banks to make its approach to the runway. You can feel the collective intake of breath amongst the passengers. It is tangible, palpable, visceral, in that little tube of pressurised air. And the outbreath as the wheels bump and find the tarmac. You have not died – yet. The worried face of your fellow traveller relaxes its frown. You are the last to leave, the stricken... A lot of people left the plane at Calgary. It was a relief, after being squashed in the window seat for seven hours, when the Glaswegian couple took their bags and filed out. A few new faces replaced those who’d reached their destination, but not nearly so many. The remaining passengers spread out, filling empty seats. Some stretched out across a middle three. After walking around a while, peering out at the runway, the airport, the faint cityscape on the plain and the line of distant mountains, he went back to his window.

‘He’s changed person in the middle of the paragraph,’ she said. But she carried on, intrigued.

This was the leg of the journey he’d been waiting for – sunset over the Rocky Mountains – so he didn’t even notice her at first, until she stopped and checked the seat number, then sat with a smile in the outer of three. ‘Hey,’ she said, casually, not inviting a response. He glanced at her, then went back to fiddling with the buttons on his Nikon. But he noticed the book she brought from her bag – it was ‘Anna Karenina’, but in Russian, judging from the Cyrillic script on the cover. He was snapping automatically, trying to get an angle on the incredible white peaks, the blue lakes, the snaking silver rivers, that would exclude the sun’s glare just enough for clarity, when the pilot announced turbulence and the seatbelt sign went on. ‘Shit,’ she said, half to him, half to herself. ‘I knew I should’ve ordered a drink. If I’m going to die, I want to die happy.’ He took one of the full miniatures of Johnnie Walker from his bag, and the second unused plastic cup that had encased the one he’d been drinking from, offered them to her. She looked at it, at him. ‘If you want it, it’s yours,’ he said. She hesitated, then smiled. ‘Thanks, that’s kind. But I don’t like whisky. A gin and tonic’s what I need.’

‘Well,’ she said to the dog, ‘That never happened. And it’s all confused. If that’s the kind of writing he does, I’m not surprised he hasn’t been published.’ But the dog wasn’t listening, it had heard someone coming upstairs, footsteps that stopped outside the partly opened door of room 14, and it growled as a couple of faces peered in. When the interlopers heard that, and she looked up, they ducked out of sight. ‘Nah, that’s not her,’ a disappearing voice said as they went back downstairs. ‘Sure looks like her though,’ said another. She frowned behind her pink-rimmed glasses. ‘Silly men,’ she said, patting the dog, but her interest was in the journal. He’d written about them, their meeting on the plane – though he’d changed things here and there.

Her eyes flitted quickly over the lines, as she turned page after page back through the outsized notebook, till noises from the terrace below rose up and in the open window. The two spies were down below and their conversation drifted upwards.

‘I’m telling you, man, she definitely bought that big house right down on the shore in West Van. We saw it from the water when we was out in the boat, my cousin Dan an me.’

‘Na, that was Oprah. Everybody knows bout that.’

‘No, it’s not that house.’

‘So what would she be doing up here in the canyon, anyway?’

‘Maybe the Scotch guy’s a scriptwriter?’

‘He’s from Scotland, bro.’

‘They make movies there. Braveheart.’

It was far from the first time Sigourney’s image had got in her way. She’d given up trying to stop the misapprehension. At times it even opened doors. So she got up from the bed and pulled the window shut on the conversation. Her dog lifted its head expectantly, but the long legs those canine eyes watched walked back to the bed, where she flicked through more pages impatiently, looking for another mention of the valley. ‘I know, it’s hot, honey. But it’ll be cooler soon and we’ll take a walk then. Maybe Gil will have turned up,’ she told the dog. ‘You like Gil, don’t you?’

Exasperated with her fruitless search, she stopped her backwards scanning, and turned to the beginning again. She started to read, and her expression changed from one of frustration to amazement. ‘Oh my God!’ The dog looked at her, as if understanding the phrase and what it signified. ‘He’s changed our names.’ And she began to read intently, her eyes flitting over the words at speed behind her pink-rims.

On the plane, unprompted, she’d said ‘You’re a little late, aren’t you?’

I looked up at her, puzzled. ‘Late? Why?’

She pointed at the Handbook to the Goldfields on my knee, an 1862 edition from the bookshop in Edinburgh. ‘The gold rush ended about 150 years ago.’

‘Well,’ I answered, laughing. ‘I thought there would still be a few nuggets left here and there.’

‘So you’re a prospector? No, I don’t expect so. But you’re Scotch. That much I can tell from your accent, and the whisky. There are a lot of you Scotch in Canada.’

‘The Scots built Canada, according to some books I’ve read. And the country I’m going to used to be known as New Caledonia, in the days before it became British Columbia.’

‘So where is it exactly you are going to?’

‘Well, I’m going to spend a week in Vancouver – I’ve rented a room on MacDonald Street, which just makes my point about the Scots – and then I’m going to head into the interior, up the canyon to a place called Cloud Falls.’

‘MacDonald is near where I live. But I don’t know Cloud Falls. Where is that?’

‘In the Gold Country, of course.’

‘Touché. But you’re not really going to look for gold.’

‘No. Anyway, most folk probably won’t have heard of Cloud Falls. It’s only about a hundred people.’

‘So if it’s not gold you’re searching for, what is so special about this little town?’

‘I’m doing research on a man who went to live there, about 150 years ago.’

‘You’re a journalist?’

‘No. It’s a long story. I think he’s a relative of mine. I’ve been ill. I’ve wanted to make this trip for a long time and when I got my strength back, I thought this was as good a time as any.’

‘I get it. Bucket list. I thought you looked sick. You’re so thin. What was wrong with you?’

‘Cancer.’

She shook her head, as if disbelieving. ‘Wow,’ she breathed.

‘Anyway, here’s to life ongoing,’ he said, raising the plastic airline cup.

‘And gold.’

‘I hope so,’ he answered. ‘Both.’

It took her a moment to realise that the writer had switched person in mid-passage again. What made someone so unsure of who they are?

‘So this is your first time crossing the Rockies,’ she said.

‘How can you tell?’ he asked, camera in hand.

‘Oh, just all those pictures you were taking earlier.’

‘Well, you’re right. And you?’

‘Oh, many times. I live in Vancouver now. Though not always.’

‘I guessed that. Your accent is...?’

‘Czech.’

Hah! He’d made her Czech!

‘Not Russian?’ He pointed at the Tolstoy, protruding from her bag.

‘No! Definitely not Russian. Though like a lot of Czechs of my generation, I can read Russian as a result of classes at school. But I’ve never read Anna Karenina before.’

‘It’s always good to leave a few classics for later life,’ he said and tossed back his dram.

He didn’t say any of that. He was nowhere near as eloquent.

‘So now you’re reborn?

‘I had to re-evaluate everything. And stop smoking, of course. I don’t know what lies ahead.’

‘Smoking, ah...’

‘I feel as if I’ve lived a very safe life, as if I’ve never done anything dangerous or foolish and it’s almost over.’

‘But you smoked, surely that’s dangerous and foolish...’

Yes, he had smoked – from the moment he first opened his father’s tobacco drawer and smelled the freshly aromatic scent tempting his olfactory nerve, he’d had warm associations with the wicked weed.

And so above the Rockies, you told this stranger the story of your quarry.

He’d switched again! What’s the matter now?

You told her the story of Jimmy Lyle and his wanderings, as you had heard it from your great-grandmother, how she remembered his solitary homecoming in 1901. Of a nineteen-year-old travelling five thousand miles in 1884 from the bare island hills, by sea and land, and sea and land, and much more land, into a desert canyon. And back again, seventeen years later, by horse, train and ship. Of that old magazine in your great-grandmother’s kitchen in Leith with the story about him entitled, ‘Friend to the Indians’. And the photo with his Native wife, and his dog, in front of the log cabin. Of how he’d been ‘Aly’, then ‘Jimmy’, then ‘Jacques’. All the things you knew about a place you’d never been to. Dead people you’d never met.

You looked at her face and she slept, so you ceased. Unlike anyone, and yet from somewhere among the thousands of faces you’d glimpsed or got to know, some recognition seemed to flow.

‘You stopped,’ she’d said quietly, without fully opening her eyes.

‘I thought you were sleeping,’

‘No, not now.’

So you’d shared a taxi from the airport, you were travelling to the same part of the city, only a few blocks away. And when she gave you the neat printed card with her name and address, her phone and email, and you exchanged that for a slip of paper from your wallet with your phone number, you felt that you’d connected, somehow.

If I’m going to die, I want to die happy, she had said. What you did not tell her was that while you’d lain in your mother’s garden and gazed up at the clouds last summer, you’d come to know a younger self that you’d ignored, someone bold and ambitious, eager for challenge and willing to take risks. You didn’t tell her that younger self was angry with you, that you felt him on your shoulder urging you on, to try at least to do one big thing while you still had time. You had been the tethered bear, walking that circle, for just too long.

When the innkeeper tapped the open door of room 14, she seemed lost in the Scotsman’s journal. He cleared his throat and tapped again. His face seemed uncertain as to whether he’d done the right thing in letting her into the room.

‘So you found out what this sacred valley is?’ she said, without more than a glance in his direction.

‘No. Nobody seems to know about it. Did you find anything in his journal? Because I’m kinda worried myself now.’

‘Not yet.’ She laughed a little, the first time he’d seen her smile and he stared intently, as if trying to compare it with what he remembered Sigourney Weaver’s smile to be like. ‘But I found myself,’ she said. She was about to add something, but a sudden grinding, clashing roar arose from somewhere outside, gradually growing so loud that it felt as if the little inn was shaking, and the dog leapt up, barking and howling.

‘CPR,’ the innkeeper shouted over the uproar. ‘It’ll be over soon.’ But the noise got louder, and the roaring and barking went on for some long minutes more.

‘That can’t do much for trade,’ she said, when the commotion was finally over. ‘How often does that happen?’

‘A few times a day,’ he answered. ‘You kinda get used to it.’

‘Do you?’ She put her glasses back on, and picked up the journal which was not a journal but a story, and a story about her, or some version of who she was. How this dying Scotsman saw her.

‘So...’ he hesitated. ‘What do you want to do now?’

‘Me, I’m going to read this. If Gil – Mr Johnson - turns up, then let me know. And in the meantime, I want you to find out where that valley is. Someone must know. Phone around, speak to people. And I want you to bring me some more tea. And some water for him.’ She gestured towards the dog.

Her tone was so naturally commanding, she could well be some big movie star. ‘Up here?’

‘Sure, why not? It’s a pretty nice room. And quiet, except for those trains.’

The innkeeper hesitated again. She had invaded his domain and now was dismissing him like a servant.

‘What is it?’ she asked.

‘It’s just...’

‘What?’

‘Are you really who I think you are...?’

‘What do you think... what is your name, anyway?’

‘Rick,’ he said. ‘And I just wondered, what your plans are, if you’re going to drive back to Vancouver or carry on elsewhere, because if you want a room here I’ll need to get one ready. And if you want food, then...’

She interrupted, ‘I’m just going to wait here for now,’ but she was already drifting back into the journal.

‘Shall I close the door?’ he asked.

‘On your way out, yes,’ she said, and turned her attention back to the Scotsman’s handwriting.

What was this, a poem?

You hear the kaark kaaark kark of consciousness.

Hugin and Munin flee ilk day,

owir da spacious eart.

Though I vex for Hugin

that he’ll no come back,

it’s for Munin I’m maistlie feart.

Two ravens flew from your shoulders,

Huginn to the hanged

Munin to the slain,

light stealers, shape-shifting

fellow travellers.

Thought and Mind

arguing forever over

the last bean in the can

That was all it said. No context, no notes. She turned the page, found the narrative thread from before.

He woke wondering where the hell he was, remembering a dream about ravens, pulled back the heavy drapes and it seemed to be getting dark. There were a few complimentary groceries in the kitchen of his suite, so he made a cup of tea and ate a biscuit, switched on the TV to discover it was early morning, not evening. His watch still had Greenwich Mean Time. He tried to calculate the time difference, and just how long he’d slept, but the arithmetic was beyond him at that moment.

So this really was British Columbia. He vaguely remembered landing, the airport with its native carvings, the long queue at passport control, coming through, drunk on whisky miniatures, feeling jet-lagged, weakly dragging his suitcase, wondering if the woman he’d met on the plane would be there at the other side of Customs as she’d said she would be. And then her waiting with her small red case, smiling at him, the taxi through the suburbs to the door outside, where she’d left him.

As the morning brightened, he went out to look around. The suite he had rented was a largish room with small kitchen on the ground floor of a wooden heritage house, painted fashionable grey. The neighbourhood was one of similarly smart suburban houses, some like Swiss cottages, others more Arts and Crafts. In one direction, the road dipped out of sight and in the distance he could see white-capped mountains across the bay. After breakfast, he’d walk there.

MacDonald Street was quite busy, a bus route to downtown, and it intersected with the much busier 4th Avenue a couple of blocks away. Commuters were already moving to wherever they were headed. He was waiting to cross at the lights, amused by the novelty of the Canadian signals, when he got a text.

hope u slept. j-lagged? if not, can i show u something? Martina

So she was real. He found a café on the corner of 4th and Bayswater, where he ate a muffin and drank coffee while he texted back: OK what? Where?

Jericho - native daughters.

OK

An hour later, she picked him up outside his suite in a green VW. As he opened the passenger door, hesitating briefly to check it was the correct side, she glanced at him curiously, as if she had doubted he’d existed too, and wanted to see him again just to prove that he did.

‘Hey,’ she said, as he got in. ‘You sleep?’

‘Yeah. But I woke too early, thanks to a flock of crows – or maybe they were ravens?

‘You sure you feel like doing this? Not too jet-lagged?’

‘Haha, I wouldn’t even know what that feels like,’ he said. ‘But when I woke, I thought it was night. I put on the tv and it was breakfast news, the anchorman was a Campbell and he was interviewing a MacAllister. There’s Scots everywhere. Very strange. So where are we going?’

‘I just thought you might like to see the oldest building in Vancouver. Thought it might get you on the road with your historical research.’

‘Sounds interesting,’ he said. In fact, he felt surprisingly good, good to be with her, good to be alive. The car came to a four way stop where a skateboarder was crossing.

A huge laminate photo image of a couple, embedded in the wall of an elaborate timber house on the corner, caught his eye. They were dressed in what seemed like smart 1950s fashions to him, posed almost nose to nose, though she was standing a step above her sweetheart. He read the picture title out loud: ‘John and Dimitra. Together Forever. So who were John and Dimitra?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know,’ she replied, pulling away. ‘Some dearly departed Greek couple. I think one of their kids keeps the place as a kind of shrine to them now. Check out the gardens. The white picket fence is plastic, by the way.’

‘Happy in the ever after,’ she added. ‘There’s a big Greek community here. It’s not all Scottish.’

‘But a lot of it is,’ he suggested. He examined the image again. John stood a step below, looking up into Dimitra’s adoring face. She was displaying a large ring on her wedding finger. ‘They’re the perfect married couple, whoever they are.’

As she pulled away from the stop, she smiled. ‘Maybe. One photo doesn’t prove anything.’

At the bottom of the hill as she turned left, he caught a glimpse of skyscrapers glinting in the sun in the other direction. Downtown, obviously.

‘Beautiful,’ he said, not thinking.

‘Isn’t it? she answered. Then neither spoke for a while. She drove quickly and confidently along a main road skirting the shore. The view across the bay skipped in and out of sight between large mansion houses on the cliff edge, towards tall peaks across the sea. He could tell it was very beautiful and wanted to go down there, to be able gaze out across that Pacific water at the mountains and the skyscrapers, to think about all the distance he had travelled.

‘You know, that would be one of things on my bucket list,’ she said, thoughtfully.

‘What is?’

‘You’ll laugh, I know. It’s to get married.’

‘Married? Who to?’

‘Oh, that doesn’t matter so much. I just want to be a bride. If I was dying, it wouldn’t matter who it was, any one of my single friends would do.’

He studied her face as she drove, saw the golden glint of mischief he’d sighted the day before. It was hard to tell if she was serious. ‘But there wouldn’t be any together forever,’ he said.

‘That’s the point, clever. Just a big party where I could be the bride. Never having been one. Yet.’ The automatic gear change clicked and the engine eased into top, as they sped away from town.

‘I don’t really understand,’ he said, after a while.

‘Maybe it’s a girl thing. My girlfriends all understood.’

‘No, I mean marriage. The need. The urge. At all. Think I’ve lived alone too long. To be with someone in that domestic way.’

‘That’s not what I wanted. And maybe that’s why I never got married. No, it’s just the life event. I want to experience it. Every little girl thinks about it, or at least they did where I come from. Her wedding day.’

‘Where do you come from?’

‘It’s a little town in Czech Republic. You wouldn’t know it.’

‘And any groom would do in this bucket list wedding, would they?’

‘Well, they’d have to look good in the photos. And play the role well on the day. You know, speeches, that sort of thing. And then leave me alone whenever I said so, once it’s all over. And divorce me if I lived.’

She put down the journal on the bed, a puzzled look on her face. Hero stared at her with his mind-reader’s eyes and she stroked his head. ‘Weird, Hero,’ she said under her breath. ‘We did say these things, or something like it.’ He’d captured something. Her eye fell on the next word and she read on.

‘So pretty straight forward then?’

‘Sure - interested?’

‘I’m afraid I’m not available. Dying men don’t make good husbands to be. You don’t know if they’re going to make it to the altar. Anyway, a beautiful woman like you has no shortage of men to choose from, I’d guess,’ he teased.

‘Not only men,’ she said. ‘This is Vancouver, after all,’

She turned off the main road, and down towards the shore, where a marina arced out into the bay. Behind a sandy cove stretched, the tide far out. They approached a small dilapidated wooden building, peeling a strange shade of dusty pink paint.

‘Jericho Beach,’ she offered.

‘So someone blew trumpets?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘The Bible story. When Jeremiah brought the walls of the city of Jericho down just by blowing trumpets.’

‘Now he’s making things up, Hero. Taking liberties. He didn’t say any of that clever stuff about the Bible.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know bible stories. I grew up in Soviet times.’

Hah!

‘Of course. It’s not important.’

She stopped and faced out across the wide bay, to the mountainous steeps on the far side, where streets of houses stretched up from the city below. ‘I think the name is a corruption. I read somewhere that an early settler had a lumber mill here and the beach was known as Jerry’s Cove, which got shortened to Jericho. Though there was a Squamish settlement here before that.’

‘And I never said that either.’

‘I sometimes try to imagine what it must have looked like, before Europeans arrived. There were three Squamish villages along the south coast here alone. And this is Hastings Museum, or the old Hastings Mill Store, as it was called. The home of the Native Daughters. It was the heart of the first lumber mill here, where downtown is now, then they towed it up here.’

‘So I suppose when the gold ran out, it was all about timber here, in the early days?’

‘In the early days of the white settlement, yes. That and salmon.’

‘I guess it was a hunter’s paradise, forests everywhere. Wild animals. Bears, wolves, beavers.’

‘But you know, they discovered a garbage pit downtown a while back while they were building, and the remains were at least 2,500 years old. You know, shells and bones and stuff. Some expert said it could be as old as 9,000 years.’

‘A midden?’

‘Yes. That’s it. A midden.’

‘Good Scots word,’ he said as he got out and wandered over to the front door, where an old iron bell swung from a new support. She hung back by the VW, sat on the bonnet and smiled, as he pulled out his Nikon and began snapping the front of the store, its shuttered windows and signs.

‘Like it?’ she asked.

He turned and looked at her sitting there watching. ‘As you say over here, sure.’ And he turned the lens towards her, focused. She crossed her legs, lifted her chin, posed, and he pressed the shutter. Gazing into the camera at the recorded image, he said ‘You don’t look very Czech,’ with a grin.

‘How should I look?’

‘Well, I always thought Czech women were tall and blonde. You know, like the tennis player.’

‘But I refuse your stereotyping. You don’t have ginger hair and a kilt.’

He clicked the shutter again, checked the picture. Again, he had the feeling she reminded him of someone. ‘True. I’m a poor specimen of my race.’

‘You are indeed. So very thin and... what’s the word?’

‘Thrawn?’ he offered, but she didn’t respond.

Instead she stood up. ‘If you say so. Anyway, I’m going in now.’

‘Let’s...’

She laid the journal down as Hero’s ears pricked up, and they both listened as a distant rumble grew. But it passed, just a truck on the highway. Turning back to the story in front of her, she said ‘It all seems a bit stagey, buddy. I’m not sure what to make of it. What is this Scotchman of ours up to?’ But she carried on.

He pushed the old wooden door of the museum open for her, and she went to squeeze past, into the gloom. For a moment they were nose to nose, eye to eye, and he realised she was exactly as tall as he was. Her scent filled his nostrils like a potent smoking drug, then she had passed him by.

Inside was a porch, with various signs and pennants pinned to a v-lined wall. A second door led to the dark interior, like a large schoolroom, or indeed a store. The air inside felt heavy with dust, laced through with the aroma of slowly aging decay, barely masked by furniture polish. It reminded him firstly of a church and then, with an aftertaste of bibliochor, his bookshop in Edinburgh, and for a moment he was back in familiar territory.

In the gloom, behind a long heavy wooden shop counter acting as a desk, a woman sat crocheting. She glanced up as they entered, as if she wasn’t expecting anyone, as if they may be the first and only visitors of the day. She put her crochet down and sat up.

‘Well, hi,’ she said. ‘Come on in. Welcome to the oldest memorial to Vancouver’s pioneer past.’ He gazed around the room at the mass of assembled artefacts. All seemed faded, sepia-coloured, a multi-paned window on an earlier era. Not a smart modern museum full of interactive gizmos, the past sealed behind plexiglass casing, here the building itself was an exhibit.

‘It dates from 1865?’ Martina asked.

‘That’s correct. Though at that time it wasn’t out here at Jericho. You have to imagine the whole of the city as virgin forest,’ the woman at the desk went on. ‘Ancient old growth trees, more than 300 feet tall. Then in 1865 an Englishman by the name of Stamp began to build a lumber mill down by the shore there, at the foot of Dunlevy. They took a flume from Trout Lake to provide steam power, and built this store to service the camp. It sold everything you could think of back then, a true emporium.’

Listening, he wandered through the exhibits, arrayed as if in a country schoolroom or a very plain Protestant chapel, yet the most fabulous of obscure objects to him lay within reach. Old mangles, pots and pans, various tools, many of them carved from wood. As he nosed around, peering at the old photos and artefacts, it occurred to him that Vancouver was almost exactly the same age as Lyle. The idea of the lumber mill would have been gestating in Stamp’s mind just as Jimmy was entering the world, five thousand miles away in Shetland, in the spring of 1864.

‘Are you from round here?’ the woman asked, curiously.

‘I live nearby,’ Martina said, ‘But I’ve never been in here before, although I have driven past many times. My friend is from Scotland and very interested in the history of the province.

‘Well, there’s plenty of history in here. And one of the early mill owners was a Scot, you know, after Stamp gave the mill up. He was a Campbell.’

‘Did you hear that?’ Martina called over to him, then turned back to the figure at the desk. ‘He thinks everything here is from Scotland. He points to street names as we drive past and tells me they’re all Scottish.’

Gil smiled over at the two women as they talked by the desk. The curator laughed. ‘Well, you know, lots of Scots came here at first, my dear. He’s right about that. And it’s from them we take much of our inspiration, them and others like them.’

‘Exactly, just as I told you.’ he said. ‘Is it all right to take a few photos?’

‘For a small donation,’ the woman replied, nodding towards a large wooden collection box on a table by the door.

‘So when did the store move up here?’ Martina asked her.

‘1930. They were going to demolish it, and so a group of ladies came together and insisted that it should be preserved. They towed it up here from Burrard Inlet, through the Narrows across English Bay, and lifted it up here on rollers. There’s a film of it you can watch if you like, just by the entrance to the Hansom Cab over in that corner there.’

The two visitors peered into the gloom in the direction she indicated.

‘It’s quite wonderful,’ she went on. ‘There’s footage of the Native Daughters aboard the Harbour Board yacht, serving a special tea. It was quite an event, you see, the mill store had a very special place in people’s hearts, because it had survived the great fire of 1866. And it had been the first post office, the first schoolroom, the first drugstore anywhere round here.’

‘There was a fire in 1866?’ he asked. He was calculating in Lyle time, that Jimmy would have been in Cloud Falls for two years by then.

‘Yes,’ Martina said. ‘Almost the whole of the town was destroyed, wasn’t it?’

The curator grimaced. ‘Sure, it was terrible. Not that there was so much to destroy back then, but it was all made of timber and went up like a rocket. They were clearing land because Vancouver had been selected as the terminus for the CPR railway, and a squall swept up a brush fire that the workers had started. The sparks fell on the town and it just exploded, and kept on burning till it was just about on top of the store. Then, like it was the hand of Providence at work, the wind changed and the store was spared. The millstore here became an emblem. It still is, to those who know the story.’

Gil was snapping photos as he listened, thinking about the news of the great fire making its way up country to the young Lyle on his uncle’s ranch in Cloud Falls. With no railway at that time, the news would have travelled by stagecoach or horseback, probably – no doubt fiercely discussed and debated, the fire and its causes, the miracle of the wind change. The story would have grown with each telling. Jimmy Lyle would have known this building and its story well.

The curator went on with her tale. ‘After the fire, the store was at the heart of the recovery operation, doling out food and emergency supplies, even acting as a morgue for the dead.’

He wandered about after that, looking at the exhibits, the thought of death vivid, as if the memory was somehow encoded in the timbers of the store. His eyes picked out a massive wooden plough, old sledges, a wooden washing machine. Cannons from 1867 when the settlement still had need of them, the Hansom cab, the old Hastings Mill safe. Some period dresses. A vast collection of woven baskets like the kind he knew Lyle had collected for the museums back east.

Then they watched the grainy film of the Native Daughters serving tea on the day in 1930 that the millstore was brought to Jericho by barge.

Afterwards Martina asked the curator, ‘So just who are the Native Daughters of BC?’

‘We are an organisation of women born here in the province. Pioneers.’

‘So I couldn’t join because I was born in Czechoslovakia?’

‘No, dear. Not if you aren’t born here.’

‘So this has nothing to do with First Nations natives?’ he added.

‘Not much,’ she answered, not elaborating, then to Martina she said, ‘You are, my dear, lovely as you are, what back in the old days, they used to call a ‘cheechako’. Someone who migrates here, in the Chinook parlance.’

‘Yes, I am a cheechako,’ Martina said, and looked to him, suddenly, with a vague glare of annoyance. She seemed somehow upset at the idea.

‘There’s a book of Robert Service’s poems, Ballads of a Cheechako,’ he volunteered, inadvertently making a no-man’s land between the curator and the cheechako.

‘Ah, Robert Service,’ the woman said. ‘Now he was a poet. We Canadians are very proud of him.’

‘But in Scotland, where he came from, he’s hardly mentioned these days.’

For a second the woman looked puzzled. ‘Scotland? Are you sure?’

‘He grew up in the shire of Robert Burns, and was schooled in Glasgow. He came out here as a banker. He ended up as the biggest-selling poet of the twentieth century, living the life of Riley in Paris.’

‘You,’ Martina laughed, ‘would have everything Scottish. But surely that can’t be correct. What about Eliot and his cats? That must have made millions.’

‘I’m only repeating what I’ve read,’ he said, holding his palms up to both.

There had been a dusty old settled pride about this native-born lady as she sat behind the old shop counter, but as she shifted into a beam of light that streamed from the window, a glamour of well-to-do assurance came over her. She stretched out across the small desk and the sunlight caught her profile.

‘I think you’ll find I’m right about Mr Service,’ she said firmly. For a second he was tempted to spout a challenge, and probably appear quite pedantic, but he smiled instead.

‘Ah well, maybe you are. I’m only a bookseller, after all,’ he said. And he put a twenty-dollar bill in the collection box by the door as they exited. No gift shop here.

Afterwards, outside, they stood silently for a while, looking out over the grandeur of the harbour to the mountains beyond.

‘That woman annoyed me,’ she said.

‘Really?’ he asked, and smiled in a slightly twisted way that didn’t turn out right. ‘I’d never have guessed.’

‘Are you teasing me?’ she said sharply. Did he twist his smile because she seemed annoyed, or because he was nervous?

‘Maybe. So what if you’re a Czech cheechako?’

She laughed. ‘And you’re very cheeky.’

‘And this is the cheek of a Czech Cheechako,’ he added and, for no reason, kissed her on the side of her face, as a joke maybe.

She put down her glasses, checked the time on her cell. Hero raised his head from the cushion of his paws, hopefully. She patted his neck fur, and said, ‘This is weird, buddy. I’m in a story.’ And she put her spectacles back on.

‘So,’ he said, ‘Tell me what I’m looking at here. What are these places called?’ And so, slowly, she began to name the various sights, from Vancouver Island in the distance, to the Sunshine Coast, Bowen Island, West Vancouver and the mountains of Cypress, Grouse and Seymour all opposite, and then Point Grey on the same shore. He tried to memorize all the names, but his mind was still reeling gently from the jetlag.

‘Okay. Enough,’ he breathed. ‘That’s all my brain can take in for now.’

‘You must be tired,’ she said, examining his face. ‘You probably want a timeout.’

‘No,’ he answered. ‘I’m enjoying this. I’ll tell you when I’ve had enough.’

‘Well, the tide’s out. We could walk back along the shore? It’s not too far to where you’re staying?

‘What about your car?

‘I can pick it up later. I could do with the walk. And you should see this piece of shoreline. It’s the last wild part, the rest has all been landscaped. There’s a nice place below MacDonald where one of the Squamish villages used to be. Tsumtsahmuls, they called it. The name’s lost now.’ So they clambered down onto the beach, and went treading their way through the wet stones and slippery surfaces.

‘You must tell me more about why you’re here,’ she told him, as they walked in the ebb along the shore. Shells crunched underfoot.

‘I told you. I want to write a book.’

‘I sense there’s more to it than just the book.’

‘Well, I suppose it’s my top bucket-list item,’ he said. ‘Things to do before you die.’ Along the seawall an impressive line of graffiti caught a blaze of sunlight. It lit up shapes and slogans unfamiliar to him, though one smallish piece Uncle George – get well soon! made them both laugh. They walked on a little further, around a headland, picking careful steps across rock and sand.

‘But why? I think I deserve a little more information. I’ve brought you to one of my secret places. You owe me more about your secrets.’

A large flock of ducks and ducklings made darting bobbing passage along the shallows. A few went far out, some were left behind.

‘Well, you are right. There is more. It’s to do with my father. Something I always wondered about. You see, he was much older than my mother, a widower, and he died when I was a boy so I don’t – I didn’t even have the chance, you know, to find out much about him, other than what my mother told me, and she had her own issues with him. She always seemed to end up talking about those.’

He stopped and peered out across the water. ‘Downtown’s stunning from here,’ he said, ‘the way the city seems to try to compete with the mountains in scale...’

‘But completely fails,’ she finished.

‘So far.’

‘They’ll never tame it,’ she said, with absolute certainty. ‘The buildings will all be thrown down and overgrown.’

‘Prophecy of doom?’

‘Certainty, in cosmic terms.’

‘You know a bit about the cosmos?’

‘It’s innate. Stardust, you know, like the song says we are.’

‘Ah yes, the great Canadian songstress.’

‘You know Joni?’

‘I grew up with her.’