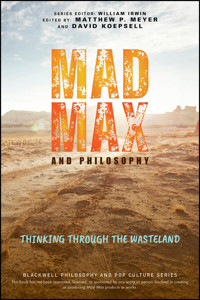

Mad Max and Philosophy E-Book

19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

- Sprache: Englisch

Explore the philosophy at the core of the apocalyptic future of Mad Max

Beneath the stylized violence and thrilling car crashes, the Mad Max films consider universal questions about the nature of human life, order and anarchy, justice and moral responsibility, society and technology, and ultimately, human redemption. In Mad Max and Philosophy, a diverse team of political scientists, historians, and philosophers investigates the underlying themes of the blockbuster movie franchise, following Max as he attempts to rebuild himself and the world around him.

Requiring no background in philosophy, this engaging and highly readable book guides you through the barren wastelands of a post-apocalyptic future as you explore ethics and politics in The Wasteland, the importance of costumes and music, humankind's relationship with nature, commerce, gender, religion, madness, and much more.

- Covers all of George Miller's Mad Max films, including Mad Max: Fury Road

- Discusses connections between Mad Max and Nietzsche, Malthus, Mill, Foucault, Sartre, and other major philosophers

- Follows Max's journey from policeman and family man to lost soul in search of redemption

- Examines the future of technology and possible impacts on society, the environment, and access to natural resources

- Delves into feminist themes of Mad Max, such as the reversal of heroic gender roles in Fury Road and relationships between power and procreation

Part of the bestselling Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture series, Mad Max and Philosophy: Thinking Through the Wasteland is a must-read for anyone wanting to philosophically engage with Max, Furiosa, and their dystopian world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 468

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

Notes on Contributors

Introduction: Doing Philosophy in the Wasteland

Acknowledgments

Part I: POLITICS AFTER THE POX‐ECLIPSE: ANARCHY, STATE, AND DYSTOPIA

1 Post‐apocalyptic Anarchism in

Mad Max

Anarchy and Apocalypse

Roaming the Wasteland

Not All Government Is Good Government

Anarchism and Voluntarism

Is This Anarchy?

It Doesn’t Have to Be Humungus

Notes

2 Even on the Road, Violence Is Not the Same as Power

“

Only Those Mobile Enough to Scavenge, Brutal Enough to Pillage Survived”

Why “Lord” Humungus Has Epithets

Having a Toadie and Going Kamakrazee

Lords and Immortans: Order and Power

Notes

3 Thomas Hobbes and the State of Nature in the Wasteland

“My Name Is Max. My World Is Fire and Blood”—Max,

Fury Road

Not Even Max Can Make It Alone

“Bartertown’s Learned. Now, When Men Get to Fighting, It Happens Here, and It Finishes Here!”—Thunderdome Announcer

“We Do It My Way”—Lord Humungus, Ayatollah of Rock‐and‐Rolla

Beyond the White Line Nightmare

Notes

4 The Political Economy of Bartertown: Embeddedness of Markets, Peak Oil, the Tragedy of the Commons, and Lifeboat Ethics

Bartertown and the Embeddedness of Markets

Peak Oil

Tragedy of the Commons

Can We Escape the Tragedy?

Lifeboat Ethics

The Future

Notes

5 From Wee Jerusalem to Fury Road: Does

Mad Max

Depict a Post‐apocalyptic Dystopia?

Pox‐Eclipse Full of Pain: Apocalyptic Themes

You Can Shovel Shit Can’t You?: Dystopian Themes

Nomad Bikers, Bulk Trouble

A Maggot Living off the Corpse of the Old World

By My Deeds I Honor Him, V8!

Two Men Enter, One Man Leaves

But He’s Just a Raggedyman

Notes

Part II: THE MAN WITH NO NAME: HEROES AND FINDING ONESELF POST‐APOCALYPSE STYLE

6 “Pray He’s Still out There”: Heroism in the

Mad Max

Films

“Down the Long Haul, into History Back”

We Don’t Need Another Hero with a Thousand Faces

We Don’t Need Another Absurd Hero

“Where Must We Go, We Who Wander This Wasteland, in Search of Our Better Selves?”

Notes

7 Bloodbags and Artificial Arms: Bodily Parthood in

Mad Max: Fury Road

Adhesion: “You Want That Thing off Your Face?”

Bonding: “Don’t Damage the Goods”

Life: “They’ve Got My Blood”

Function: “If You Can’t Stand Up, You Can’t Do War”

Integration: “Got Everything You Need”

Life or Integration: “We’re the Only Ones Left”

Arguing for Integration: “That’s My Head!”

Tattoos and Artificial Arms: “Now We Bring Home the Booty”

Conclusion: “He Doesn’t Know What He’s Talking About!”

Notes

8 The Meaning of Life According to

Mad Max: Fury Road

Nux’s Faith, Crisis, and Purpose

Max: From Survival to a Meaningful Life

Furiosa as a Role Model for a Better Self

Objective Values

A Meaningful Life on the Fury Road?

Notes

Part III: BUILDING A BETTER TOMORROW! ETHICS IN

MAD MAX

9 What Saves the World? Care and Ecofeminism

Who Killed the World?

I Thought You Girls Were Above All That

We Are Not Things

Breeding Stock and Battle Fodder

Out Here, Everything Hurts

We’re Not Going Back

Notes

10 Seeking the Good Life in the Wasteland

Life in the Wasteland

Who Killed the World?

Moral Force Patrol

Nietzsche or Aristotle? Immortan Joe or Furiosa?

What the First History Man Knew

“We Might Be Able to … Together … Come Across Some Kind of Redemption”

“Where Must We Go, We Who Wander This Wasteland in Search of Our Better Selves?”

Notes

11 “We’re Not to Blame!” Responsibility in the Wasteland

Henchmen and Marauders: A Problem of Many Hands

“Witness!” War Boys and Responsibility

“Some Got the Luck … and Some Don’t”

Murderer or Just Kamakrazee?

“Where Must We Go …?” Who’s Responsible?

Notes

12 “Look, Any Longer out on That Road and I’m One of Them, You Know?”: Madness in

Mad Max

Terminal Crazies: Madness and Contagion

“I Was Sick!”: Responsibility and Madness

Hanging by a Thread: The Furrow of Reason

“Unleash My Dogs of War”: Confinement and Animality

“I Am Your Lord!”: Cults, Shared Psychosis, and Responsibility

“… One of Them, You Know?”

Notes

13 Justice, Reason, and the Road Warrior: A Mechanic Reads Plato

Reason Belongs in the Driver’s Seat

Administrator of Street Justice

Real Men Eat Dog Food and Fear the Wasteland

Notes

Part IV: MOTHER'S MILK: GENDER AND INTERSECTIONALITY

14 Homecoming as Homemaking: The Rise of the Matriarchy in

Mad Max: Fury Road

A Stranger Comes to Town …

Time for a New Plan

Nietzsche’s Critique of Idealism

Something Like Redemption

Notes

15 Liberating Mother’s Milk: Imperator Furiosa’s Ecofeminist Revolution

The Inhumanity of the Citadel

Humanized Humans and Animalized Humans

The Citadel’s Animalized Humans

Feminized Animals and Animalized Women

Immortan Joe’s Unnatural Empire

“We Are Not Things!”

“Who Killed the World?”

Where Must We Go?

Notes

16 Demarginalizing Aunty Entity and Dismantling Thunderdome

What’s Race Got to Do with It?

“You Can Shovel Shit, Can’t You?”

“Welcome to Another Edition of Thunderdome!”

“But How the World Turns”

Black Dystopia: “So Much for History”

Notes

17 Gayboy Berserkers at the Gate: Sex and Gender in the Wasteland

We Don’t Need Another (S)Hero: Beyond Thunderdome, Beyond Sex and Gender

Everybody’s Looking for Something

This Ain’t One Body’s Tell, It’s the Tell of Us All

Notes

Part V: WASTELAND AESTHETICS: MUSIC, FASHION, AUSTRALIA, AND NATURE

18 Driving Insanity, Chaos, and Emotion: The Music of

Mad Max: Fury Road

“High‐Octane Crazy Blood Fillin’ Me Up”

“Oh, What a Day! What a Lovely Day!”

“You Want That Thing off Your Face?”

“I Can’t Wait for Them to See It … Home … the Green Place”

“If You Can’t Fix What’s Broken, You’ll Uh … You’ll Go Insane”

“Max. My Name Is Max … That’s My Name”

Notes

19 Carapaces and Prosthetics: What Humans Wear in

Mad Max: Fury Road

Guzzolene and Aqua Cola: Bodies, Machines, and Survival

Staring at Furiosa

Reflecting on Max

In Closing: Thinking About the Body in

Mad Max

Notes

20 Does It Matter How Australian the Apocalypse Is?

What Is It for a Film to Feel Australian?

Does the

Mad Max

Franchise Owe Something to Australians?

Is It Important for Australians to See Themselves Represented?

Making Sense in a World Gone Mad

Shouldn’t Films Come in All Flavors?

Everyone Should Have an Aussie Hero

Notes

21 The Moral Aesthetics of Nature: Bioconservativism in

Mad Max

Man Versus Machine

Broken Bodies in the Wasteland

Nature and Dignity in

Mad Max

Each of Us in Our Own Way Was Broken

No Nature, No Dignity

Notes

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover Page

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright Page

Notes on Contributors

Introduction: Doing Philosophy in the Wasteland

Acknowledgments

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Index

WILEY END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT

Pages

ii

iii

iv

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

83

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

135

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

Series editor: William Irwin

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, and a healthy helping of popular culture clears the cobwebs from Kant. Philosophy has had a public relations problem for a few centuries now. This series aims to change that, showing that philosophy is relevant to your life—and not just for answering the big questions like “To be or not to be?” but for answering the little questions: “To watch or not to watch South Park?” Thinking deeply about TV, movies, and music doesn’t make you a “complete idiot.” In fact, it might make you a philosopher, someone who believes the unexamined life is not worth living and the unexamined cartoon is not worth watching.

Already published in the series:

Alien and Philosophy: I Infest, Therefore I AmEdited by Jeffery A. Ewing and Kevin S. Decker

Avatar: The Last Airbender and Philosophy: Wisdom from Aang to ZukoEdited by Helen De Cruz and Johan De Smedt

Avatar and Philosophy: Learning to SeeEdited by George A. Dunn

The Avengers and Philosophy: Earth’s Mightiest ThinkersEdited by Mark D. White

Batman and Philosophy: The Dark Knight of the SoulEdited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp

BioShock and Philosophy: Irrational Game, Rational BookEdited by Luke Cuddy

Black Panther and Philosophy: What Can Wakanda Offer the World?Edited by Edwardo Pérez and Timothy Brown

Dune and Philosophy: Minds, Monads, and Muad‐DibEdited by Kevin S. Decker

Dungeons and Dragons and Philosophy: Read and Gain Advantage on All Wisdom ChecksEdited by Christopher Robichaud

The Expanse and Philosophy: So Far out into the DarknessEdited by Jeffery L. Nicholas

Game of Thrones and Philosophy: Logic Cuts Deeper Than SwordsEdited by Henry Jacoby

The Good Place and Philosophy: Everything Is Fine!Edited by Kimberly S. Engels

The Ultimate Harry Potter and Philosophy: Hogwarts for MugglesEdited by Gregory Bassham

The Hobbit and Philosophy: For When You’ve Lost Your Dwarves, Your Wizard, and Your WayEdited by Gregory Bassham and Eric Bronson

Indiana Jones and PhilosophyEdited by Dean A. Kowalski

Metallica and Philosophy: A Crash Course in Brain SurgeryEdited by William Irwin

The Ultimate South Park and Philosophy: Respect My Philosophah!Edited by Robert Arp and Kevin S. Decker

The Ultimate Star Trek and Philosophy: The Search for SocratesEdited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker

Star Wars and Philosophy Strikes Back: This Is the WayEdited by Jason T. Eberl and Kevin S. Decker

Westworld and Philosophy: If You Go Looking for the Truth, Get the Whole ThingEdited by James B. South and Kimberly S. Engels

Wonder Woman and Philosophy: The Amazonian MystiqueEdited by Jacob M. Held

Forthcoming

Ted Lasso and PhilosophyEdited by David Baggett and Mary Baggett

Joker and PhilosophyEdited by Massimiliano L. Cappuccio, George A. Dunn, and Jason T. Eberl

The Witcher and PhilosophyEdited by Matthew Brake and Kevin S. Decker

For the full list of titles in the series, see www.andphilosophy.com.

MAD MAX AND PHILOSOPHY

THINKING THROUGH THE WASTELAND

Edited by

Matthew P. Meyer and David Koepsell

Copyright © 2024 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 750‐4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data

Names: Meyer, Matthew P., editor. | Koepsell, David R. (David Richard), editor.Title: Mad Max and philosophy : thinking through the Wasteland / edited by Matthew P. Meyer, David Koepsell.Description: First edition. | Hoboken : Wiley, 2024. | Series: The Blackwell philosophy and pop culture series | Includes index.Identifiers: LCCN 2023021906 (print) | LCCN 2023021907 (ebook) | ISBN 9781119870487 (hardback) | ISBN 9781119870494 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781119870500 (epub)Subjects: LCSH: Mad Max (Motion picture : 1979) | Motion pictures–Philosophy. | Popular culture–Philosophy.Classification: LCC PN1997.M2534 M33 2023 (print) | LCC PN1997.M2534 (ebook) | DDC 791.43/72–dc23/eng/20230523LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023021906LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2023021907

Cover images: © James O’Neil/Getty Images; © chaluk/Getty ImagesCover design: Wiley

Notes on Contributors

Lance Belluomini did his graduate work in philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley; San Francisco State University; and the University of Nebraska‐Lincoln. He’s recently published essays on Tenet and The Mandalorian in The Palgrave Handbook of Popular Culture as Philosophy. He’s also contributed chapters to a variety of Wiley‐Blackwell volumes such as Inception, The Ultimate Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and Star Wars and Philosophy Strikes Back. Clearly, the film Mad Max: Fury Road has had an influence on Lance. For instance, when rushing to get somewhere, he exclaims, “Fang it!” When unimpressed, he shouts, “Mediocre!”

Kiki Berk is an associate professor of philosophy at Southern New Hampshire University. She received her Ph.D. in philosophy from the VU University Amsterdam in 2010. Her research focuses on the philosophy of death and the philosophy of the meaning in life, especially in the works of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean‐Paul Sartre. In her free time, she wanders the Wasteland in search of her better self.

Daniel Conway is a professor of philosophy and humanities, an affiliate professor of film studies and religious studies, and a courtesy professor in the School of Law and the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University. He has lectured and published widely on topics in post‐Kantian European philosophy, political theory, aesthetics (especially literature and film), American philosophy, and genocide studies. He hopes that he is awaited, shiny and chrome, in Valhalla.

Laura T. Di Summa is an assistant professor of philosophy at William Paterson University. She has published extensively on film, visual arts, and criticism. She is the co‐editor with Noël Carroll and Shawn Loht of The Palgrave Handbook for the Philosophy of Film and Motion Pictures and the author of A Philosophy of Fashion Through Film. After modeling her biking style on Mad Max and further refining it while pushing her son’s stroller, she is now considering investing in a War Rig.

Ian J. Drake teaches in the Political Science and Law Department at Montclair State University. He obtained his Ph.D. in American history from the University of Maryland and his law degree from the University of Richmond. His teaching interests include the American judiciary and legal system; the U.S. Supreme Court and constitutional history; the history and contemporary study of law and society, broadly construed; and political theory.

David H. Gordon is an assistant teaching professor of philosophy at Loyola University Maryland in Baltimore, where he specializes in the history of philosophy, environmental philosophy, and the interdisciplinary study of science and religion. He has toiled long and hard in Socratic poverty, working as a mechanic and carpenter, as well as on fishing boats in Alaska. He can also turn a mean baseball bat on his lathe. When he’s not asking why there is something rather than nothing, he wonders why Johnny the Boy didn’t just throw the hacksaw at the cigarette lighter.

Jacob M. Held is a burnt out, desolate man. He wanders the Wasteland of academia, this blighted place, learning to live again. In the meantime, he is a professor of philosophy and assistant provost for academic assessment and general education at the University of Central Arkansas. He specializes in political and legal philosophy and nineteenth‐century German philosophy, and he dabbles in medieval philosophy and the philosophy of religion. He has written many essays at the intersection of philosophy and popular culture and edited several volumes, including Wonder Woman and Philosophy (Wiley Blackwell, 2017), Stephen King and Philosophy (Rowman and Littlefield, 2016), and Dr. Seuss and Philosophy (Rowman and Littlefield, 2011).

Thanayi Jackson is an American historian. Born and raised in San José, California, she spent most of her days trying to escape capitalism as a disciple of Rock before a Griot banished her to History where, after a great odyssey through the University of Maryland, she assumed the identity of semi‐mild‐mannered professor. Jackson is a contributing author to Black Panther and Philosophy and has held positions at San José State University, Berea College, and, currently, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. A fangirl of the Reconstruction period, her work examines transitions from slavery to freedom and all things Black Power. Jackson is a lifelong student of punx, drunx, freaks, geeks, revolutionary jocks and hippies, hip hop intellectuals, and heavy metal queens. As a result, she abides by a punk rock pedagogy whereby anything can be learned, everything can be deconstructed, and nothing can be lost.

Clint Jones earned his Ph.D. in social and political philosophy from the University of Kentucky and currently teaches full‐time at Capital University in Ohio. In addition to numerous contributions to pop culture and philosophy titles, he has published articles and book chapters on utopianism, environmental philosophy, and critical theory. His recent published books include Apocalyptic Ecology in the Graphic Novel (McFarland); Stranger, Creature, Thing, Other (Cornerstone Press); and a forthcoming edited volume, Contemporary Cowboys: Reimagining an American Archetype in Popular Culture from Lexington Books. Though it is a mistake to hope, Clint nevertheless hopes his work will help you enjoy your Mad Max experience more fully—but he’s just a doctor, not a fortuneteller.

Justin Kitchen teaches philosophy at San Francisco State University and California State University, Northridge. His work centers around virtue ethics and virtue epistemology; it draws often from Stoic philosophy and Indian Buddhism. As a fallback career, he has also been considering joining a zealous adrenaline‐fueled war party in search of guzzolene.

David Koepsell has been teaching philosophy for 28 years at such places as the University at Buffalo, the Technical University of Delft, and now Texas A&M. He has authored and edited a dozen books and over 50 journal articles, chapters, and reports and has lectured around the world. Long a fan, he has used pop culture in his courses and research for as long as he has been teaching. Recently, he started the CinePhils podcast with fellow philosopher Rob Luzecky, which is about films and philosophy. He thinks his life would be complete if only he had the last of the V8 Interceptors, with Phase 4 heads, 600 horsepower through the wheels!

Karen Joan Kohoutek is an independent scholar who has published about weird fiction and cult films in various journals and literary websites, with recent works on Black Panther and Robert E. Howard and Doris Wishman’s film oddity Nude on the Moon. She has also published a novella, The Jack‐o‐Lantern Box, and the reference book Ici Repose: A Guide to St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, Square 3, about the historic New Orleans cemetery, through Skull and Book Press. In her personal life, she is an Aunty and, at the same time, just a raggedy woman.

Leigh Kellmann Kolb is an associate professor of English at East Central College in Missouri. Her writing has appeared in publications including Sons of Anarchy and Philosophy, Philosophy and Breaking Bad, Twin Peaks and Philosophy, Amy Schumer and Philosophy, The Handmaid’s Tale and Philosophy, The Women of David Lynch: A Collection of Essays, and Better Living Through TV. She’s also written for Vulture and Bitch Magazine and serves as a screener and juror for film festivals. She shows Mad Max: Fury Road to her Composition II students at the end of each semester so they can take with them the pleasure of critically analyzing pop culture in hopes that they will help save—not kill—the world.

Andrew Kuzma is a bioethicist at Advocate Aurora Health Care in Milwaukee. He earned his Ph.D. at Marquette University. His research interests include moral distress, narrative ethics, the role of community in cultivating virtue, and Citadel‐era conceptions of shiny and chrome. With his feral child, Madeleine, and the Imperator Lisa, he wanders the Wasteland as a man reduced to a single instinct: write.

Greg Littmann roared down the scorching asphalt in his battered white Toyota, with Wasteland bandits in close pursuit. He was tortured by the memories of the world that had been and was gone forever, a world in which he had been an associate professor of philosophy at SIUE. Once he had published on evolutionary epistemology, the philosophy of logic, and the philosophy of professional philosophy, among other subjects. He also had written numerous chapters for books relating philosophy to popular culture for the general public, including volumes on Big Bang Theory, Black Mirror, Doctor Who, Game of Thrones, Star Trek, and Star Wars. But now there was only the road, and the eternal hunt for food and fuel, and the human predators. He could see in the rear‐view mirror that they were closing in, howling. The 18‐wheeler loomed out of the red dust dead ahead, coming right at him. It was covered in metal spikes and leather‐clad warriors. Screaming, Greg instinctively threw up his arms to protect his face. The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates believed that the only genuine harm that can befall a person is for them to become morally worse. If that’s true, Greg was just fine.

Matthew P. Meyer is an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire. His main areas of study are existentialism, phenomenology, and psychoanalysis. He has written a study entitled Archery and the Human Condition in Lacan, the Greeks, and Nietzsche: The Bow with the Greatest Tension (Lexington, 2019) and has published articles and chapters on Nietzsche and film. He has also published in several Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture series books, on Sartre (and The Office), Nietzsche (and House of Cards), aesthetics (and Westworld), and Beauvoir (and The Good Place). Like Max, he’s afraid he’s beginning to enjoy that rat circus out there.

Edwardo Pérez, after being a pianist accompanying Ton Ton’s saxophone, escaped Bartertown, seeking refuge with The Tribe Who Left. Years later, Edwardo found himself teaching rhetoric and critical theory as a professor of English at Tarrant County College in Hurst, Texas—where Edwardo also writes speculative fiction and contributes awesome chapters on popular culture and philosophy. Inspired by Savannah Nix, Edwardo continues to search for knowledge of the pre‐apocalyptic world, when “those what had gone before had the knowing and the doing of things beyond our reckoning … even beyond our dreaming.”

Jacob Quick is a lecturer and Ph.D. candidate in the Institute of Philosophy at KU Leuven. His doctoral research focuses on Simone Weil, Jacques Derrida, and animal ethics. When he’s not reading, writing, or teaching philosophy, you can find him McFeasting in the halls of Valhalla.

Aeon J. Skoble is the Bruce and Patricia Bartlett Chair in Free Speech and Expression at Bridgewater State University, where he is also a professor of philosophy and co‐coordinator of the program in philosophy, politics, and economics. He is the author of Deleting the State: An Argument About Government (Open Court, 2008) and The Essential Robert Nozick (Fraser Institute, 2020); the editor of Reading Rasmussen and Den Uyl: Critical Essays on Norms of Liberty (Lexington Books, 2008); and co‐editor of Political Philosophy: Essential Selections (Prentice‐Hall, 1999) and Reality, Reason, and Rights (Lexington Books, 2011). In addition, he writes widely on the intersection of philosophy and popular culture, having co‐editing The Simpsons and Philosophy (Open Court, 2000), Woody Allen and Philosophy (Open Court, 2004), The Philosophy of TV Noir (University Press of Kentucky, 2008), and The Philosophy of Michael Mann (University Press of Kentucky, 2014), and he has been a contributor to 14 other books on film and television. He would like to thank Lord Humungus for Helpful contributions to this essay.

Anthony Petros Spanakos is a professor of political science and law at Montclair State University. He is the co‐editor of the Conceptualising Comparative Politics book series (Routledge) and has written extensively on Latin American politics, foreign policy, and popular culture and political theory. He was recently in a very changed Australia where quarantine rules suggested new possible directions for future Mad Max movies!

Joshua L. Tepley is a Professor of Philosophy at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire. He has a B.A. in Philosophy from Bucknell University and a Ph.D. in Philosophy from the University of Notre Dame. His current research interests include free will, personal identity, ontology (the study of being), and the intersection between philosophy and science fiction. He really hopes that he never needs, or becomes, a Bloodbag.

Paul Thomas is a project associate in the Inequality and Human Development Programme at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, India. He loves dissecting movies to bring out philosophical understandings from them. Being a first‐time contributor to Wiley’s Philosophy and Pop Culture series, he thoroughly enjoyed writing the essay just like how Max finds happiness in dealing with his unexpected encounters in the Wasteland.

Introduction: Doing Philosophy in the Wasteland

The Mad Max movies put the audience on the edge: on the edge of apocalypse, on the edge of social breakdown, on the edge of morality, on the edge of our seats. Throughout the franchise, we see Max, and many other characters, lose ties to what could be considered a “normal” life. All of this begins “just a few years from now.” But despite Max’s insistence that he has been reduced to the instinct to survive, deep down he is still attracted to “righteous causes.”

As Max himself says in the opening dialogue of Fury Road: “I am the one who runs from the living and the dead.” In some ways Max’s journeys across the Wasteland are like doing philosophy: frustrating, difficult, often painful, but eventually enlightening. Both “hunted” and “haunted,” Max is driven to extreme situations in which he wishes he didn’t have a choice—in every movie he essentially evades the role of savior before assuming it. Maybe the haunting is a good sign in any case. It means Max still has a conscience—or most of one. Thus, Max as quasi‐hero invites us to think about what we would do in this post‐apocalyptic world of “fire and blood.” What politics could we build? What ethics could we salvage for parts? The external conditions are abysmal. What about the internal ones?

Max’s story echoes heroes and anti‐heroes across the ages, recapitulating the paths taken by great adventurers as well as thinkers. An innocent, lawful inception, the loss of love and family, the search for meaning in a world gone mad, and the discovery of embers of humanity in the desert. The Wasteland is not just a place, as T. S. Eliot’s poem of the same name makes clear, it exists among us and within us. It is a place ripe for self‐discovery and for musing about the nature of humanity, for finding our essence, for discovering our souls.

Max’s setting also invites us to think about what living would be like with all the comforts of modern western life stripped away. In that way, many themes in the films provide useful contrasts to our own lives and lifestyles. In the essays that follow, we will see the stripped‐down world of Max analyzed according to its politics, heroics, ethics, aesthetics, and more. We will see conventional views of these ideas tested—and we will consider whether these new ways of thinking apply to our own world.

As stark and dire as the world of Mad Max is, George Miller always strikes a chord of hope, which is how we close this project, in the hopes it enriches your enjoyment of the films, as well as of philosophy. We hope that you enjoy reading the book and that you too find the Wasteland an apt place for philosophizing.

Acknowledgments

While Max appears “alone” in the beginnings of the films, we realize pretty quickly that, for better or worse, he is not. Neither were we alone in the creation of this volume. First, we want to thank all of our contributing authors for their excellent ideas, fabulous writing full of wonderful insights, and patience in assembling this volume. Like Max’s journeys, the creation of this volume led to new places we didn’t expect. We’d like to thank Bill Irwin, the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series editor, for his encouragement to put forward the volume, his advice and guidance, and for generally shepherding us through every step of the Wasteland. We’d also like to thank Will Croft and Charlie Hamlyn and the whole publishing team at Wiley Blackwell for turning this mad idea into a reality.

Matt would like to thank David for agreeing to co‐edit and assemble this book together. Oddly, we both had the idea to assemble this volume for the first time almost immediately after seeing Fury Road, but it was only upon realizing that was not the last installment that we, along with Bill, realized that it would be a valuable contribution to the Philosophy and Pop Culture Series. Many thanks to David for his amazing ideas for essays and for his invaluable editing work throughout the assembly of the volume. Matt would also like to thank his family, Jill and Charlie, for putting up with moments of editing “insanity.”

David would like to thank his family: Vanessa and the kids, Ame and Alex, as always, for putting up with his madness and his obsessions, including with popular culture and philosophy, as well as his parents who introduced him to film and film criticism at an early age. He is indebted to Matt for helping to marshal the resources and channel his procrastination into a final work of which we can all be proud.

Part IPOLITICS AFTER THE POX‐ECLIPSE: ANARCHY, STATE, AND DYSTOPIA

1Post‐apocalyptic Anarchism in Mad Max

Aeon J. Skoble

In George Miller’s 1979 film Mad Max, we are introduced to a post‐apocalyptic dystopia in which official law enforcement is weak and predatory gangs are powerful. In three sequels, the breakdown of traditional social order is made even more explicit, and the protagonist’s struggle, first for revenge and then later for justice, more difficult. Is this “anarchy”? Does anarchy entail violence, or is peaceful anarchism possible? What are the results of social breakdown? Is this portrayal of a lawless world realistic? This essay will explore the meanings of concepts such as anarchy, government, society, and order by looking at the social backdrop of this film franchise.

Anarchy and Apocalypse

Of course, a world of marauding biker gangs and violent warlords is exactly what people tend to imagine when they think of anarchy. Anarchy is associated with chaos and disorder, whereas words like society and government are associated with order. But just as the presence of a government is no guarantee of a functional and just social order, the absence of government shouldn’t be taken to imply their lack.

To begin with, it’s worth noting that the word anarchy doesn’t even mean “no government” or “no order.” It means “no rulers.” The root word archon, for “ruler,” is the same as in the word monarchy. So, modified by the mono‐ prefix, it means “one ruler” and modified by the negating a‐/an‐ prefix, it means “no rulers.” To equate “no rulers” with “no government” or “no order” is to beg an important question about the nature of social order and the extent to which it can be achieved without coercive authority imposed from the top down. The world Mad Max lives in offers us some useful touchpoints for thinking about this, but also, as we’ll see, some less‐than‐useful ones.

We’re never told explicitly what apocalyptic events happened, but context clues and scattered bits of dialogue imply wars for scarce resources, which of course are now more scarce. It’s never explained why this would lead to the complete collapse of the social order. In the first film, it hasn’t completely vanished. Max Rockatansky (played by Mel Gibson in the first three films and Tom Hardy in the fourth) is a police officer, of course, so there’s some organized law enforcement apparatus. But, as the film depicts, their authority is often flouted and the biker gang that drives the plot seems to act with impunity, terrorizing people at will. So the police department seems like a vestigial force, greatly attenuated but still trying to protect innocents from the gangs. The vestiges of the court system that we see in the film are similarly attenuated and essentially toothless. Part of the problem seems to be that the structures in place for rights‐protection are so remote and vestigial as to be insufficient for deterring the biker gangs and other outlaws. In this respect, Mad Max resembles a “Western” film where, even though there’s technically a legal authority, it is either physically remote or else too weak to adequately respond to criminality. For example, in the 1993 Western Tombstone, there’s a sheriff and a marshal, but the criminal gang “the Cowboys” acts with impunity, as if they need not worry themselves about law enforcement. Similarly, the “Nightrider” gang can roam freely and act as predators. What little police enforcement still exists can’t pose a significant threat to them. Once Max becomes a vigilante, he is able to dispatch the gang, as his willingness to match their level of savagery permits strategies that might previously have been unavailable. With his family having been murdered and his revenge taken, Max himself is no longer part of the vestigial law enforcement apparatus, taking to the road as a loner.

Roaming the Wasteland

In the sequel films, we see Max on his aimless roaming, and his encounters with other pockets of people show an even further detachment from the old civilization he left behind. In the first film, there are towns and cities, people are still conducting commerce, and while there seem to be fewer people around, the ones who are there seem relatively healthy. Times are tough but recognizable. In each sequel film, this is less and less the case. Max is roaming not on the outskirts of a city, but through a literal Wasteland, and the few concentrations of people are exclusively either straggling bands of survivors or predatory gangs. There’s evidence of environmental spoilage, but it’s possible to grow food in some places, and while gasoline is scarce, there’s obviously still enough to power all the cars, trucks, and motorcycles everyone uses. So it never becomes any more clear what exactly is the extent of the “apocalypse” or why it led to a breakdown of the social order. The explanation we might extract from Westerns, that in a frontier setting, authority structures are so removed as to be inefficacious, doesn’t seem like it would explain what we see in these films.1 In 1981’s The Road Warrior, a small refinery has been converted to a tiny walled settlement and is besieged by a violent gang led by the mutant Humungus (Kjell Nilsson). The residents of the settlement hope to escape “to the coast” but we have no indication of whether that would be more hospitable—after all, the setting of the original film is near the coast. In 1985’s Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, Max encounters a town of sorts, governed by the despotic Aunty Entity (Tina Turner), but its governance is capricious and in some ways medieval, a regression from the Australia Max would have grown up in. He also encounters a colony of orphaned children, whom he helps find a way to Sydney, which we learn has been destroyed. In 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road, Max encounters a community ruled by mutant warlord Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays‐Byrne). Neighboring “communities” are also ruled by warlords.

It’s never explained how any of these situations might have emerged. As far as post‐apocalyptic action films are concerned, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Cinematically, it can be sufficient that the protagonist find themself in an outlandish and barbarous world because the drama derives from the protagonist’s reactions to the situation. We don’t need to know the origins of the founding of Bartertown, for instance; we just need to see how it operates and what dilemmas and challenges it poses for Max. However, what is acceptable or even advantageous to leave out of a movie is not acceptable for drawing philosophical conclusions. If I made a movie about a peaceful and prosperous society with a wise and benevolent monarch King Bob, it might be an excellent movie, but it would be a mistake to infer from it that “monarchy must be a desirable political system, because look how great King Bob is.” Similarly, one can be a fan of the Mad Max series without concluding that “anarchism must be bad because it would be terrible if we had violent mutant warlords.” While the question of how Immortan Joe’s Citadel came to be is unimportant cinematically, it’s worth thinking about how realistic it is if we’re trying to think about political philosophy.

Not All Government Is Good Government

One reason not to take these scenarios as examples of anarchism is that they seem less like examples of “no rulers” than they are examples of “bad rulers.” Immortan Joe and Aunty Entity are in fact rulers. They have power over their territories and the people in them. The people they rule acquiesce to (even if not always enthusiastically endorse) this control. That makes them rulers. Noting that they’re not the sorts of rulers we would expect to see in liberal democracies doesn’t make them not rulers. While it seems true that the Australia Mad Max is roaming around in no longer has central, continent‐wide governance, it’s also true that small, localized pockets of governance have emerged, such as Bartertown and the Citadel and Bullet Farm. That’s importantly not the same thing as anarchism. To define anarchism as “the lack of the kind of government I like and am familiar with” won’t do. We can disapprove of Immortan Joe’s rule while noting that he is in fact the ruler of the Citadel. That’s not any different from disapproving of Hitler while noting that he was in fact the ruler of Nazi Germany.

Anarchism and Voluntarism

What would it actually look like to have no rulers? It would have to mean that organized systems of production and trade would be voluntary. People can work together for their mutual benefit and common interest. They can even adopt rules for adjudicating disputes and establishing boundaries for both conduct and physical space allocation. None of these features of social living require their imposition by coercive authority, though of course that’s the manner in which we’re most familiar with them. The seventeenth‐century philosopher Thomas Hobbes argued, however, that we wouldn’t be able to sustain such a system of voluntary cooperative order because each person is a potential predator, and our fear and distrust leads us to regard each other as enemies, rendering social cooperation impossible.2 This was why he argued for absolute monarchy as a “solution” to this problem, and this has been the underlying justification for coercive authority—if sometimes only tacitly—ever since.3 On Hobbes’s view, it makes perfect sense that Lord Humungus would attract and lead vicious predatory thugs to live by raiding others. Everyone in the gang is in sufficient fear of the Humungus’s power as to motivate them to cooperate with gang activity and focus on common goals. That’s exactly how Hobbes understood the sovereign: if everyone is in sufficient fear of the sovereign’s power, only then can they be trusted to refrain from predatory behavior toward one another. For Hobbes, then, anarchism is bad not because we might get rulers like Immortan Joe, but because having no rulers at all is worse than having rulers like Immortan Joe.

There’s not really good evidence for this, it turns out. The history of rulers offers far more examples of tyranny and enslavement than it does of egalitarian democracy. In contrast, there’s abundant evidence of organically emerging orders based on mutual gain and benefit. It’s just that we don’t tend to classify those as “governance.” We tend to conflate “governance” with “ruling,” since the most obvious examples (good and bad) of the former come from the latter. But they’re conceptually distinct. The evolution of international merchant law in the Middle Ages and the evolution of the common law in English villages are but two of the many examples of social order that arises from and is based on mutual benefit. This sort of “governance” is created by people’s voluntary compliance.4 Voluntary and mutually beneficial social orders are, contrary to Hobbes’s assertion, more stable than oppressive orders, which invite both rebellion and invasion precisely because people are less likely to acquiesce to such orders when alternatives are available. That’s not to say a tyrant may not have an iron grip on power for some particular timespan. Immortan Joe seems to be pretty secure in his reign, though of course it’s a rebellion by some of his subjects that precipitates the plot of the movie, and when Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) returns triumphant, the folks in the Citadel are perfectly happy to have her be in charge of the water. On the other hand, there’s no cause for rebellion against an institution that provides mutual benefit.

The classic contrast between the worldview of Hobbes and that of seventeenth‐century philosopher John Locke is based on (among other things) the idea that people can recognize the mutually advantageous nature of treating others as equals and cooperating with them for shared goals, though even for Locke, there is a reason for having some kind of ruler.5 If we didn’t have one, he argued, we might find it “inconvenient” to not have things like an impartial forum for dispute resolution. So—by consent—we authorize rulers who can provide things like this. This is far closer to an ideal of voluntary social order than what we see in Hobbes, and includes a right of rebellion against abusive sovereigns.

We can also see historical evidence of institutions for impartial dispute resolution that are not based on a ruler’s prerogative, but rather emerge from people’s voluntary agreement.6 Consider firms like the American Arbitration Association. Parties in conflict agree to have their dispute settled by this firm rather than go to court. How would a firm such as this thrive? If it were known to be biased, people wouldn’t agree to go there. But if they have a reputation for fair processes, people will be attracted to them. Impartial dispute resolution is one of the things Locke argues would be lacking in anarchism, thus necessitating some kind of sovereign power. But note that courts run by the sovereign need not be unbiased. For one thing, they’re likely to be biased in the sovereign’s favor, but beyond that, we have ample evidence of state‐run courts being tainted with racism, or gender or class bias. A private arbitration firm with a reputation like that would not stay in business long. Also, the procedures can be unfair in other ways than overt bias. The titular Thunderdome of the third film isn’t “biased” in the ways we normally think of bias, but at the same time, trial by combat doesn’t seem like a particularly fair dispute resolution procedure. The American Arbitration Association, on the other hand, like similar firms, offers a much more reasonable mediation system. This is an example from the twentieth century, but similar institutions can be found as far back as the Middle Ages.

Is This Anarchy?

When people think of Mad Max–type scenarios as “why anarchism would be bad,” it seems to be a matter of conflating “government” and “good government.” The liberal democracy of Australia had effective policing, equality among citizens, a prosperous economy, rights protection, and courts of law. So if all of that gets replaced by War Boy raids rather than commerce, biker gangs who don’t fear the police, and “two men enter, one man leaves” dispute resolution, we can all agree that that’s bad. But it’s unclear why we should think that’s what anarchism is.7 Anarchism isn’t what you have when this particular government goes away; it’s what you have when the idea of rulers goes away. In post‐apocalyptic Australia, a reasonably decent government has degenerated into the worst‐case scenario of bad government: small pockets of tyrannical warlords who wield power for the sake of their own advantage, without regard for any conception of equality or rights or consent. While we’re not shown this explicitly, one can see how gangs like the Nightrider’s from the first film could evolve into something like the army of the Humungus or the War Boys of the Citadel. That’s the social evolution of a political arrangement: a very primitive one, to be sure, based on power and fear rather than a conception of the common good, but a political one nonetheless. That’s in contrast with, not an example of, voluntary communities of consent‐based social order. People think that the world of Mad Max is one of anarchy because the social order has broken down, but the lack of social order isn’t what produces anarchy; it’s what produces tyrannical warlords. The inefficacy of the police in the first film seems like it’s the reason for predatory gangs, but of course the real world has many examples of predatory gangs. And the thinning of the police department shouldn’t entail “now the Nightrider gang can take over”—there’d be nothing stopping anyone else from challenging that gang’s authority. In the movie, that only describes a handful of individuals, though in later films we see it’s gang versus gang. That’s how we get the political evolution of the Citadel, the Bullet Farm, and Gas Town.

It Doesn’t Have to Be Humungus

Taking Locke’s conception of “inconveniences” as a model, anarchism would be undesirable if it meant we had no way of protecting ourselves from predators or adjudicating disputes. But interestingly, two things are observable empirically. First, even when we have a sovereign power, we are still liable to be preyed upon, sometimes because the ruler’s protection is remote and inefficient (as in the 1979 film) and other times because the ruling power is itself predatory (as in the 2015 film); and we likewise can fail to have fair and unbiased dispute resolution (as in the 1985 film, or, say, more realistic situations such as depicted in To Kill a Mockingbird8). Second, mechanisms for protecting ourselves against predators, and institutions of reasonable dispute resolution, can arise and have arisen outside of political authorities, as people voluntarily cooperate for mutual advantage. So the post‐apocalyptic world of Mad Max is not really an instructive example of “why anarchism would be bad” after all, despite it making for exciting and interesting filmmaking.

Notes

1

For an analysis of social order in Westerns and in perhaps surprisingly similar Samurai films, see my “Order Without Law: The Magnificent Seven, East and West,” in McMahon and Csaki eds.,

The Philosophy of the Western

(Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010).

2

See Thomas Hobbes,

Leviathan

(London: Penguin 1951 [1651]).

3

For an analysis of this, see my

Deleting the State: An Argument About Government

(New York: Open Court, 2008). See also Michael Huemer,

The Problem of Political Authority

(Chicago: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

4

Classic sources for analyzing these phenomena include Harold Berman,

Law and Revolution

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983), and Friedrich Hayek,

Law, Legislation, and Liberty

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973). More recently, see Gary Chartier,

Anarchy and Legal Order

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), and Edward Stringham, ed.,

Anarchy and the Law

(Oakland, CA: Independent Institute, 2007).

5

See John Locke,

Two Treatises of Government

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967 [1690]).

6

See Robert Axelrod,

The Evolution of Cooperation

(New York: Basic Books, 1984).

7

Sources as varied as

Christianity Today

(

https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2015/may‐web‐only/mad‐max‐fury‐road.html

) and

Jacobin Magazine

(

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2021/02/mad‐max‐capitalism

) make this inference. The columnist for

Inquisitr

makes explicit these common assumptions (

https://www.inquisitr.com/2382225/five‐ways‐mad‐max‐movie‐franchise‐destroys‐anarchy‐bliss/

).

8

The 1960 novel by Harper Lee and the 1962 film by Robert Mulligan, in which an all‐white jury in the Jim Crow South convicts a black man, despite compelling evidence that he could not have committed the crime, due to racial bias.

2Even on the Road, Violence Is Not the Same as Power

Anthony Petros Spanakos and Ian J. Drake

The Mad Max movies depict a dystopian world in which people hope and struggle to live until, and perhaps past, tomorrow. There are roads and encampments, but few provide more than temporary, uncertain havens, and even the more developed towns like Bartertown are marked by insecurity and instability. Lives are “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”1 because of the constant threat of arbitrary acts of violence, often committed in enclaves ruled by warlords or on the open road. In most contexts, there is no disinterested third party to adjudicate between the competing claims of, say, a biker and a road warrior, and so daily life is an unending state of “warre … of every man against every man.”2 As the quotes suggest, the situation appears inspired by the works of the great British philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) who argued that outside of an organized state, there are no morals, no possibility of justice or injustice. Rather, the state of nature leads to a struggle unto war in which, driven by needs and desires but bound by nothing, the person (or group) who can inflict the deadliest violence dominates. But that dominion can never be stable because even the greatest warrior sleeps and is thus vulnerable. Hobbes argued that the only way to escape this situation of perpetual danger was to recognize a sovereign to whom all consenting people ceded their natural liberty in exchange for security.

The Mad Max movies seem to depict such a world where people are in a vicious Hobbesian state of nature. But then why does the physically imposing Lord Humungus (Road Warrior) need the title “Lord” if his power comes from his violent capabilities? Why is there a Toadie to announce him? Why does Immortan Joe in Fury Road need rituals of releasing water and stories of Valhalla to motivate the War Boys when they go into battle and, eventually, turn kamakrazee? Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) claimed that although fear was fundamental to stable and effective rule, it did not guarantee legitimacy.3 Max Weber (1864–1920) famously distinguished power and authority, arguing that power involved force but authority assumed the legitimacy to make decisions and, if necessary, coerce others.4 And contemporary philosopher Byung Chul Han (b. 1959) has argued that the use of violence is an effort to exercise power without mediation and is proof that the one lacks sufficient power to project his or her will on the other.5 As we’ll see, though Mad Max films seem Hobbesian, Han’s understanding of power, obedience, and ritual turn out to be more fundamental.

“Only Those Mobile Enough to Scavenge, Brutal Enough to Pillage Survived”

The aesthetics of the Mad Max