5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Orontius and Mafalda

- Sprache: Englisch

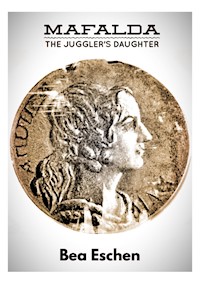

During a visit to her birthplace, Mafalda, the third daughter of the juggler Orontius, finds an ancient coin in the ruins of a chapel where Saint Catherine was celebrated in 1551. The coin shows the profile of a head that resembles hers in every detail. Full of curiosity as to who this woman from the distant past was, she and a childhood friend set off for Egypt and St Catherine's Monastery. This is the beginning of an exciting journey full of historical events, love and Mafalda's spiritual insights as she searches for her identity.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 224

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Mafalda, the Juggler’s Daughter

BEA ESCHEN

Copyright © 2023 by Bea Eschen

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Foreword

This is a work of fiction with historical references. Names, characters, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Chapter

One

THE YOUTHFUL FACES of the three sisters glowed in the light of the flickering flames. Maren, Dorothea, and Mafalda prepared for the evening meal and sat down by the crackling fire. Their mother Hildegard handed them a platter of fried fish, eggs, beans, and grain porridge, from which they each took a portion. Mafalda, the youngest of the family, helped herself generously to the honey-sweetened porridge. Her eldest sister, Maren, took the spoon from her hand. "My dear, don't overdo it. We all like it."

"Why don't you eat your fill of the main meal? Then I can have your porridge on top of mine," Mafalda replied cheekily.

Maren shook her dark curls. She loved her lively little sister, but she shouldn't always get what she wanted.

The other sister, the sturdy Dorothea with the sparkling eyes, spoke up. "You can have my share."

"Thank you," Mafalda laughed, reaching for a generous portion. She had won.

Maren paused. Dorothea always did the opposite of what she wanted. As so often before, Maren was annoyed by Dorothea's stubbornness.

"The fish is delicious, Father," Dorothea praised as she pulled the bones from her mouth pretending not to notice Maren's reaction.

"In big waters you catch big fish, in small waters you catch good ones!" her father replied.

In the afternoon Orontius had indulged in his favourite pastime. The forest pond near which he had set up camp with his wife and three daughters contained carp and pike bred by the local monastery. When he asked if he could fish in the pond for his meals, the monastery's pond keeper told him to take only the biggest pike. The pond had been standing for a long time and the pike had grown too big. The bigger they got, the more they ate the carp that were needed to grow new pike.

Orontius did not need to be told twice. Fishing was rewarding and fun. The pike were of considerable size and easily baited with frogs on his home-made line. With a chuckle he remembered how his rod had twitched time and again. Often, however, all he had pulled out of the water was a small carp, which he threw back into the pond.

Satisfied, Orontius enjoyed the warming fire and his family. The girls and his wife were happy and had enough to eat. "We're going to stay here for a few weeks," he announced. "I made arrangements with the abbot. He has compassion for people like us and appreciates the wisdom we bring from the world."

"Yes, people like us," Mafalda said, suddenly looking sad. "It wasn't long ago that a gentleman in the market called us the devil's rabble!" She looked over at Dorothea, who nodded in agreement. "We were wearing our feather dresses and doing the bird dance," Dorothea explained, "what's wrong with that? The audience clapped enthusiastically and laughed at us. Maybe we wiggled our hips too much and that made him angry?" The daughters looked at their father expectantly.

"You know, women are quickly condemned as witches if they behave a little differently. That's why we should be careful of people like him. Besides…" Orontius paused, "do not forget that we are the travelling people, the lawless and homeless, lacking everything that gives security and honour. The lives of other people are surrounded by the signs of borders and the rights of a homeland. They think they are better than us."

"Why do we need the abbot's mercy?" Maren asked. "Even if they think they are better than us, we are no less worthy than the sedentary people!"

Orontius thought for a moment. "Well, the vagabonds have always been despised by the noble societies. That makes us vulnerable, and people like that nobleman at the market take advantage of that."

"What would he gain by calling my sisters a bunch of devils?" Maren asked.

"He uses it to demonstrate his power over others," Orontius replied. "It brings out the worst in people when it comes to their standing in society."

Dorothea rolled her eyes in disgust. "Although, as keepers of our cheerful artistry, we are very welcome to clergy and laity, and bring joy to the nobles during their court and church festivals with our performances!"

"Exactly," Orontius agreed. "This is why I do not understand why we are looked down upon. The terrible thing is that we are also known as the devil's children and hated by the Church. It is a shame that the travelling race is denied the right to partake of the sacraments of Christianity."

There was a pause for the family to reflect.

"Did they also despise you in the monastery when you were a monk?" Mafalda asked.

Orontius thought. "No, but I was an outsider because I liked to do tricks. That way I could communicate with God. The others just prayed - day in, day out."

• • •

Much had changed since Orontius left the Franciscan monastery and he and Hildegard set out with their troupe. In those days, all they needed was the cart they called the Ark, which they took over from the old juggler Eberlein.

In the meantime, the family was accommodated in two horse-drawn carriages, as there was not enough room in the Ark for the parents and their three growing daughters to sleep. The second carriage, which the daughters called their Nest, was set up as a place for them to sleep and rest, while the Ark also served as a place for cooking and shelter on rainy days.

On the other side of the pond, the other members of the troupe set up camp, including the poet William and his family of six, various minstrels, and former nuns and monks who had gradually joined Orontius' troupe. The flames of the scattered campfires they had lit around the edge of the small pond reflected on the smooth surface of the water. As if from a magical world, the soft sounds of the lute, accompanied by the rhythmic beats of the tambourine, filtered through the natural surroundings.

The troupe had a law that everyone followed: no one should feel alone, but each member gave the others enough space to enjoy a respectable distance. At the same time, their collective spirit gave them the strength to overcome the challenges of their colourful lives and to support each other in providing the necessities of life.

There was one significant difference between Orontius' daughters and the other, particularly female, members of the vagabond community. Maren, Dorothea, and Mafalda could read and write. Their father was well versed in all matters of Christianity and worldly affairs and was able to teach his daughters anything that could be put into words. Over time, each of the girls developed her own handwriting, learned to read, and acquired a knowledge that their peers could only dream of. But with this knowledge came danger. Young women were usually uneducated and had no choice but to marry and have children. Moreover, educated women were quickly accused of witchcraft because of their different mindsets. Orontius knew this too, and he warned his daughters to be careful in their daily activities, not to be arrogant towards others, and to hide their knowledge as best they could, using it only for their own safety.

Mafalda's thirst for knowledge was insatiable. It was difficult for her to pretend to be different from who she really was. "Father, may I look at the religious icon again today?" she asked as she stuffed the sweet porridge into her mouth.

"Of course. Go ahead, my dear, take it. And then it's time for bed. I wish you a blessed night."

The three sisters cleared their plates and disappeared into their carriage. The candle at Mafalda's bedside was not to be extinguished for a long time, for, as she had done so many times before, she studied the religious scene depicted in the small box-tree icon. Her father had explained its meaning in detail. This tiny piece, so small that she could roll it back and forth in the palm of her hand, played a significant role in her father's life. Its sentimental value was deeply ingrained in him, and this precious icon would be his support in his old age. For Mafalda, looking at the small artefact triggered something quite different: a burning interest in all things old and venerable.

One day in 1551, something happened that was to be a turning point in Mafalda's life. The family decided to make a detour via Siegen, while the rest of the troupe continued south-east towards Koblenz. The town of Siegen and its wooded surroundings had a special significance for Orontius' family. His late mother had been a native of Siegen, and Orontius had spent over two decades at the Siegen Franciscan monastery. Years later, in August 1534, Mafalda was born in Flecken, a small village not far from Siegen, later called Freudenberg. Six years later, the town and its castle were destroyed by a devastating fire. The Count of Nassau rebuilt the centre of the village in parallel rows of houses made of clay and wood.

Mafalda was eager to see her birthplace, and as the family felt at home in the area, no one objected.

They trundled into the village on muddy roads and settled into a small inn, where they celebrated their arrival with a hearty meal of venison, beans, and bread. It was something special to be served a meal without having to work for it. Later, as they sat back in their carriages with full bellies in search of a place to spend the night, their spirits were high. A tree-shaded campsite on the banks of a small river called the Weibe, near the centre of the village, provided plenty of firewood. Soon the family had a crackling campfire.

Mafalda watched the loose sparks rising from the blaze. Her eyes were shining. "Father, have you seen the old castle tower?" she asked.

"Yes, you can't miss it. I think the tower is the only thing left of the old castle. The fire destroyed almost everything."

"Some of the walls are still standing," Mafalda objected.

Orontius grinned. "I didn't think you'd missed that."

"What did the castle look like when it was still standing?" Mafalda continued.

Orontius pondered. "It must have been built before the 11th century. Only the low walls were of stone, the rest was of wood. The gatehouse impressed me; it had a heavy portcullis. The courtyard, the residential and farm buildings, the barns, and stables were not visible from the outside. I remember that near the castle there was a small chapel dedicated to St Catherine. A chaplain celebrated mass there with the congregation."

"Do you mean St Catherine of Alexandria?" Mafalda asked.

"Yes, that's who I mean."

"Who is this woman?" Dorothea interrupted.

"She is a saint," Mafalda replied. Zeal lit up her face. "St Catherine's Monastery at Sinai serves as her memorial."

"Where is Sinai?" Dorothea asked.

"In Egypt." Mafalda replied promptly.

The parents exchanged glances.

Dorothea looked at her sister in surprise. "How do you know all this?"

"I read it in a newspaper at the last church festival we went to. A merchant from Basel lent it to me for a while." Mafalda picked up her dress and stood up. "I'm going to explore my birthplace."

"Be back by nightfall," her mother said. "And please, be careful!"

Mafalda nodded. It was not the first time she had set out on her own. She knew the dangers that could befall a young woman.

The place where the old burnt castle stood drew her like a magnet. It wasn't just the ruins that fascinated her. It was also the place where adventurers, treasure hunters and other shady folk hung out, searching for ancient artefacts that had been buried, hidden, or overlooked by others. Mafalda did not count herself among them, for she was not out to make a deal, but simply interested in man-made objects from the past.

The remains of the walls, covered with thick moss, showed the passage of time. Mafalda stuck her fingers into the damp, soft growth and felt a tingling desire. Something was about to happen over which she had no control. It was as if time stood still, for what she was experiencing was beyond reality. A woman with noble features appeared before her, dressed in a white robe that clung softly to her body. Mafalda was taken by her shapely contours and reached out to touch her body. The woman, who resembled a goddess, did not retreat; she came closer, took Mafalda's hand, and guided it to her body. Mafalda accepted the invitation, moved closer and began to caress her breasts and hips. The beauty smiled at her sensually and pulled Mafalda greedily close to her.

At that moment Mafalda realised that the woman was from the distant past and that her appearance was a mirage. The present hit her like a blow. Her hands were still buried in the damp moss. She was not sure what she was looking for, but her instincts told her it had to do with her encounter with the goddess. She needed to touch and see the mysterious something to understand what had happened.

One of her fingertips hit something hard. She dug deeper, breaking through the layer of moss, and tried to pull the object out. As she did so, she felt herself tearing at the fine limbs of the rootless plant. The hard object was enclosed in the green cushion; it had been hidden by the fine plant for centuries and was tightly embedded in it.

Finally, Mafalda got hold of it. She carefully pulled it out and examined it, but first she had to remove the dirt. A coin! Hastily she took her handkerchief from her dress pocket and polished it.

What she saw took her breath away. She recognised herself in the full profile of her head. Several times Mafalda turned the coin between her fingers. The head was only embossed on one side. Why? She brought the coin closer to her eyes to see better. Perhaps the embossing had rubbed off on the back? But no, now she saw the outline of flames leaping from the centre of a raging fire.

She had to show the coin to her father; he would have a plausible answer to her confusion. Why was her face on the coin? She looked at the profile again. The shape of her head in side view, with the straight bridge of her nose, the full lips, the round chin, the high forehead - they were strikingly similar details of her own! Was she dreaming? No, she felt the cool metal in her hand and squeezed the coin to make sure it was real.

Mafalda followed the river and reached the family's camp by nightfall. Hildegard looked up in relief. She knew her daughter's thirst for knowledge and the carelessness that often accompanied it. Mafalda trekked over mountains and through valleys to further her education. Although she was the youngest at seventeen, she was far ahead of her sisters in terms of knowledge.

"You're glowing! Have you found something?" Orontius inquired.

"This coin." Mafalda handed it to her father. He examined it carefully. "For God's sake - it's your head!"

The family gathered around him to get a better look.

"You have a double!" Dorothea exclaimed.

"One from the distant past!" Orontius looked at the coin through his magnifying glass, which he always carried in his waistcoat pocket for just such an occasion. "The year 415 is stamped on the edge. The coin dates from the early fifth century."

"Who is this woman?" Mafalda asked.

Orontius pondered. "Well, it could be the wife or daughter of a mint master. They were free to design their own coins. I imagine it is a family coin. Besides," … he rubbed it, "it's made of copper - it's not valuable."

"What do the flames on the reverse mean?" was Mafalda's next question.

"I have no answer to that. The flames can mean many things." Orontius mused. "Maybe this woman died in a fire. Or perhaps the master of the mint wanted to express something else."

"Perhaps the lady had a fiery temper!" Dorothea interjected. Orontius grinned.

"He must have loved her very much," Hildegard said, moving closer to her husband so that she could touch him. He smiled at her. "I should have a coin minted with your head on it."

"And the three of us would be on the back!" Mafalda suggested.

They all laughed. Mafalda always managed to bring the family together with her humour. Then she got serious. "Father, I need to know who this woman was. She looked like me, lived 1100 years before my time, and someone thought she was important enough to immortalise her on a coin! There is something that links me to her. I must find out what it is that makes me like her."

"But child," Hildegard said, "it may be a coincidence that you resemble her."

"You can know many things unconsciously, just by feeling them. I know there is a connection between her and me. The time gap between us makes the mystery even more interesting. Also," Mafalda continued, "there was a goddess who appeared to me like in a dream. I feel she has something to do with the meaning of the coin!"

Orontius straightened up. His life had always been about his impulses. He was open to adventure, to new knowledge, and he liked to be challenged by puzzles. The coin with his daughter's face reawakened his old longings to unravel mysteries and learn about the world, for which he was now too old. He understood Mafalda's urge to find out about the woman on the coin, especially since the goddess's appearance could mean a link to the pagan spiritual world. So he was not averse to Mafalda's idea of travelling. However, he wanted to sleep on it and discuss it with his soulmate before making a final decision. "Let's eat and enjoy our first evening back home. Mafalda, William and his children will arrive tomorrow. We will discuss it with him. William has the wisdom of a poet and knows things that people like us don't."

Slowly, William's mule approached. The wooden wheels of the carriage behind the animal dug into the mud, adding to its burden. Inside the carriage sat the widower's six children, three of them boys. The eldest, Engelbert, poked his head through the opening of the tarpaulin as they arrived at Orontius' camp. His eyes were fixed on Mafalda.

William, his father, pulled on the reins and brought the panting animal to a halt. He descended slowly from the carriage seat and tipped his hat elegantly. "Greetings, with joyful delight, in the golden evening sun."

Engelbert had inherited nothing from his father. One wondered if father and son had ever exchanged a sensible word. He lacked all the usual manners and barely spoke. It was suspected that he was linguistically inept, since his father waxed poetic on almost every occasion and only spoke in the vernacular when scolding his children.

Instead of greeting the family, Engelbert walked straight up to Mafalda and smiled at her. Mafalda was noticeably irritated by the attention, took a step back to get away from his immediate vicinity and admonished him, "Engelbert, behave yourself!"

Immediately, the lanky young man took a few steps to the side, never taking his eyes off her.

They grew up like brothers and sisters. Mafalda was the only one who treated Engelbert with respect. She liked him because he was different. Even if strangers found him threatening because of his unusual behaviour, she knew he had a kind heart and wouldn't hurt a fly. In the last few weeks, however, he had taken a different interest in Mafalda. She knew this was common among young men, but she consciously rejected Engelbert's attention, feeling nothing for him but sisterly love.

The fathers of the two families greeted each other with a warm embrace. Their joint performances at the nobles' castle feasts, church squares, fairs and marketplaces brought fun and joy to the local communities and many guilders to the troupe. Although Orontius was not as agile as in his younger days, he could still perform some amazing tricks. He could stand on his head and spin his legs in a circle or do cartwheels without touching the ground with his hands. William's job was to comment on Orontius' feats with appropriate poetry, which was sometimes so funny that the spectators held their stomachs, and the old women squeezed their legs together for fear of urinating in their underwear. The two families had even managed to save money, which was unusual for the travelling people.

"Join us! We have enough food for everyone," Orontius invited the extended family. The girls obediently sat by the fire while the boys stoked it. Hildegard and Maren went into the Ark to prepare a meal and returned with a wooden platter filled with stockfish, rabbit meat, bread, and cheese. William's family took plenty - the smacking of their lips could be heard as a sign of their enjoyment and gratitude.

When they were full, Orontius told the poet all that had happened. As he listened, the poet turned the coin in his hand and fell silent. He looked closely at the image of the head and at the reverse with the raging flames. Orontius knew his friend well enough to see that something was going through his mind that would help unravel the mystery.

"The chapel where St Catherine was celebrated and the place where the coin was found has a connection," he began. "Sinai, the monastery of Saint Catherine, is the place where the answer is buried."

Mafalda looked at him excitedly. "I have to go there!"

"How will you get there?" Hildegard asked.

"By boat!" Mafalda replied.

Everyone understood that she meant it. There were two sides to Mafalda. Her childish side was looking for fun and jokes. But her adult side was serious, persuasive, and sometimes surprisingly knowledgeable. What she had just said left no room for ambiguity. Her adventurous spirit, her courage and her strong will were breathtaking.

William turned to Orontius. "I know a merchant by the name of Piero Visentin. He sails twice a year from Venice to Alexandria to exchange goods. He takes on passengers and pilgrims in both directions."

"Women too?" Orontius asked.

"Yes, but Mafalda was to travel in company," the poet replied.

Engelbert stepped forward. "Me!" he shouted into the circle. Everyone knew that Engelbert did not understand the implications of his offer. All he understood was that his beloved Mafalda needed a companion, and he wanted to give her one before anyone else offered.

"Take him, my eldest son! He will accompany your child and guide her on her way," the poet enthused. "We will share the cost."

"You are very generous, my friend," Orontius said.

"In the forest I met thee. From the safe grave thy bounty raised me. Blest me with spirits of life. See me in thy everlasting debt."

"But William." Orontius laughed. "That is in our past! Thou shalt not feel thyself in my debt."

The poet did not answer. He meant what he said.

It had become a legend among the travelling people how Orontius had restored the poet's joy of life, who had once dug his own grave in the forest because he was tired of life. This incident earned Orontius the nickname of God's juggler.

Hildegard turned to her husband anxiously. "Mafalda is still very young. Will she be safe?"

Orontius took his wife lovingly in his arms. "My dear Hildegard, travel educates. It is a chance for our youngest daughter to see the world in a different light."

Hildegard trusted her husband and was convinced by his words. But she also knew her way around the world. "The road from Alexandria to the monastery is long," she mused aloud.

"There are organised caravans that make the journey. Many pilgrims join them," William explained, "and Piero Visentin knows the place and will be able to help from Alexandria."

Chapter

Two

MAFALDA STOOD at the railing of the giant threemaster, the Santa Neothea, and waved goodbye to her family. No, she was not sad - far from it. She was filled with a mixture of adventure and excitement at the unknown distance. Her chest rose and fell under the heavy breaths of her inner tension and her cheeks glowed. Engelbert stood beside her, staring unrestrainedly at her rising and falling breasts, while she restrained herself from giving him the slap he deserved for his indecent behaviour in this place and time. She would save it for later, it flashed through her mind as she sent a final kiss to her parents and two sisters.

The crew hoisted the sails, a rising wind from astern gave them the necessary impetus, and the mighty ship began to move. The travellers waved to their loved ones one last time, the white handkerchiefs of those left behind becoming dancing dots until the crowd in the Venetian harbour faded into a blur and then disappeared altogether.

The voyage would take weeks. Mafalda was not afraid because she knew what to expect. She was one of the few women who could read, and she knew about the diseases and cruelties of the high seas. Plague lurked in the corners of rat-infested old ships, and when it broke out, there was no turning back. She read of an unscrupulous captain who, out of greed, starved his sailors to death for a paltry profit, and enjoyed watching the sharks feast on their corpses. To quell the rising waves of restlessness, she tried to block out the images of bloody fights between prisoners and guards, beheadings, torture, rape, and other atrocities.