Mainstream E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Inkandescent

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

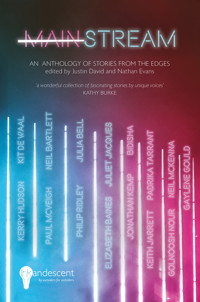

Mainstream brings thirty authors in from the margins to occupy centre-page. Queer storytellers. Working class wordsmiths. Chroniclers of colour. Writers whose life experiences give unique perspectives on universal challenges, whose voices must be heard. And read: Aisha Phoenix, Alex Hopkins, Bidisha, Chris Simpson, DJ Connell, Elizabeth Baines, Gaylene Gould, Giselle Leeb, Golnoosh Nour, Hedy Hume, Iqbal Hussain, Jonathan Kemp, Julia Bell, Juliet Jacques, Justin David, Kathy Hoyle, Keith Jarrett, Kerry Hudson, Kit de Waal, Lisa Goldman, Lui Sit, Nathan Evans, Neil Bartlett, Neil Lawrence, Neil McKenna, Ollie Charles, Padrika Tarrant, Paul McVeigh, Philip Ridley, Polis Loizou. The anthology is edited by Justin David and Nathan Evans. Justin says, 'In publishing, it's often only the voices of a privileged minority that get heard and those of 'minority' groups—specifically the working classes, ethnic minorities and the LGBTQ+ community—don't get the amplification they deserve. We wanted to bring all those underrepresented groups together in one volume in order to pump up the volume' 'a wonderful collection of fascinating and unique stories by unique voices' KATHY BURKE

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MAINSTREAM

Table of Contents

Title Page

MAINSTREAM

Praise for MAINSTREAM

MAINSTREAM | An Anthology of Stories from the Edges

FOREWORD

INTRODUCTION

HOME TIME | Kathy Hoyle

GIANT | Lui Sit

IN THE SHELL MUSEUM | Padrika Tarrant

EASY PEELERS | Lisa Goldman

THE SPINNEY | Gaylene Gould

THE INITIATION | Bidisha

HAPPY ENDING | Golnoosh Nour

THE BEACH | Hedy Hume

GOING UP, GOING DOWN | Nathan Evans

TWICKENHAM | Neil Bartlett

BLEACH | Neil Lawrence

LAST VISIT | Alex Hopkins

A REVIEW OF ‘A RETURN’ | Juliet Jacques

SCAFFOLDING | Giselle Leeb

DILATED PUPIL | Ollie Charles

SEROSORTING | Justin David

IT MAY CONCERN | Keith Jarrett

PARTNERING | Aisha Phoenix

THE BIRDWATCHERS | Julia Bell

OUR KIND OF LOVE | Paul McVeigh

THE RELUCTANT BRIDE | Iqbal Hussain

THE WEIGHT OF MY REVENGE | Kit de Waal

COUP DE GRACE | DJ Connell

A LIFE THAT ISN’T MINE TO SEE | Kerry Hudson

PIXMALION | Polis Loizou

THE DICK OF DEATH | Neil McKenna

THE FLOWER THIEF | Jonathan Kemp

NOTES FROM A COMPOSER | Chris Simpson

ALIGNMENT | Elizabeth Baines

SUNDAY | Philip Ridley

BIOGRAPHIES

SUPPORTERS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Also from Inkandescent

Inkandescent Publishing was created in 2016

by Justin David and Nathan Evans to shine a light on

diverse and distinctive voices.

––––––––

Sign up to our mailing list to stay informed

about future releases:

––––––––

MAILING LIST

––––––––

follow us on Facebook:

––––––––

@InkandescentPublishing

––––––––

on Twitter:

––––––––

@InkandescentUK

––––––––

and on Instagram:

––––––––

@inkandescentuk

Praise for MAINSTREAM

‘In these locked down and unfocused times the short story is a much-needed respite from the current Covid-19 bleakness. With Mainstream, Inkandescent has gathered together a wonderful collection of fascinating and eclectic stories. Sad, funny, horrifying and demystifying, the unique voices within take us on an open-minded journey around world. Loved it.’

KATHY BURKE

––––––––

‘A riveting collection of stories deftly articulated. Every voice entirely captivating: page to page, tale to tale. These are stories told with real heart from writers emerging from the margins in style.’

ASHLEY HICKSON-LOVENCE,

author of The 392 and Your Show

––––––––

‘A triumphant celebration of exiled voices’

CASH CARRAWAY, author of Skint Estate

Published by Inkandescent, 2021

––––––––

Selection and Introduction © 2021 Justin David and Nathan Evans

Individual contributions © 2021 the contributors

Cover Design Copyright © 2021 Joe Mateo

––––––––

Justin David and Nathan Evans have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the editors of this work.

––––––––

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without written permission of Inkandescent.

––––––––

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

––––––––

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers’ prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that win which it is printed and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the

subsequent purchaser.

––––––––

ISBN 978-1-912620-08-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-912620-09-8 (ebook)

www.inkandescent.co.uk

MAINSTREAM

An Anthology of Stories from the Edges

––––––––

Edited by Justin David & Nathan Evans

for everyone who’s ever been kept out

because of who you are or where you are from,

come in ...

Tell me your stories

Let them exist

Turn off the spotlight for a single minute

I’m angry and I am not sorry

––––––––

Tell me your stories

Show me your worth

I am the antimatter strangled at birth

I’m angry and I am not sorry

––––––––

Cos I’m in the dark for most of it

A highly elliptical orbit

I’m angry and I am not sorry

––––––––

We don’t need permission anymore

We don’t need permission anymore

Stand back and watch us take the floor

Coming through the front door

Andy Pisanu, Memory Flowers

—PERMISSION 2020

FOREWORD

I wrote my first short story when I was seven years old. It was a brief and tragic tale about a young boy called Tim who received a new bike for his birthday and died in a subsequent crash. Years later, I was struck by the name of my protagonist—Tim. I’d grown up in an Asian household, went to a mixed comprehensive school in Rayners Lane, and as a profoundly Deaf woman of Pakistani heritage, diversity was at the centre of my life. And yet, in the stories I read (and wrote), I had – albeit subconsciously—subscribed to the idea that protagonists should have ‘proper’ names and exist within a white-British vacuum.

It took years of education, active reading, and cultural analysis for me to unpack these notions and look beyond the white heteronormative blur that books sell to us. Working at Spread the Word, London’s leading literary development agency, enabled me to learn about the importance of pushing for change within the publishing industry, and the value in creating more opportunities for writers from different backgrounds to expand our bookshelves. In the past four years, I have seen progress and change. However, as our recent report Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing shows, there is still a long way to go.

The report—conducted by Dr Anamik Saha and Dr Sandra van Lente, exposed how the book industry’s tunnel vision has created a cultural production system that harms writers of colour. It highlighted the lazy tropes and misassumptions about what readers want; and how books are selected and marketed in line with this. Further, it demonstrated that writers of colour are often pressurised into unethical performance gymnastics, believing that they must modify their work to fit into a prepared packaged mould—simplifying, restricting and editing their imaginations.

The same summer that the report was published, Spread the Word formed a new connection with independent publishing press, Inkandescent, who approached us to request support with their call out for submissions for their new anthology: Mainstream. They wanted to create an anthology unrestricted by theme and subject that celebrated talented writers and the stories they wanted to write. Just this: the stories that they wanted to write. Over time, I became increasingly engaged with this project; enamoured by the enthusiasm that Justin and Nathan brought to the book, and their focus on platforming talented writers from diverse backgrounds.

Emerging writers are published alongside more experienced writers in this collection, creating and fostering a new community. This is a unique feature that anthologies offer: a statement to writers that your stories are safe in this space and you are amongst those who appreciate your differences. Further, the gathering of multiple voices in a collection reinforces plurality and diversity. It tells us that in this big, wide world there are billions of individual protagonists, beyond the Tims, each of them—rightfully—occupying the central role in their own lives, and in their own narratives.

––––––––

Aliya Gulamani

Spread the Word

INTRODUCTION

The idea for an anthology had been floating around since we set up Inkandescent in 2016. We started by publishing our own work and then the books of a few other underrepresented writers. By 2019 we felt more established and ready to up our game. We consulted ‘The Oracle of Publishing’ (aka Sam Missingham) about how Inkandescent might bring our books to a wider audience (and become a sustainable business). Sam suggested an anthology of short stories as a calling-card: it had worked for other independents, she said. So that clinched it.

We knew of other anthologies, which had begun a conversation about diversity in publishing: Common People—An Anthology of Working-Class Writers edited by Kit de Waal, The Good Immigrant—an anthology of BAME writers edited by Nikesh Shukla and Speak My Language—an anthology of LGBTQ+ writers edited by Torsten Højer. We wanted our anthology to stand in solidarity with those titles and to represent all those underrepresented groups, which as far as we were aware, had not been placed together in one book before.

Inkandescent was founded ‘by outsiders for outsiders’, to celebrate original and diverse talent and to publish voices and stories the mainstream neglects—specifically those of the working class and financially disadvantaged, ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ+ community and, crossing the Venn diagram, those with physical disabilities and mental health issues. Because often it’s only the work of a small privileged group which gets seen and read. Those less privileged in the population-at-large aren’t given the amplification they deserve. Our collection would ‘pump up the volume’.

With the help of Daren Kay, our comrade-in-copywriting, we worked through a number of ‘concepts’, but it was our designer, Joe Mateo, who nailed it: he sent us a digital scrawl of one word—Mainstream—with a line through the ‘Main’. A title was born.

We wanted Mainstream to feature an equal number of established and emerging writers. Our next step was to invite fifteen of our favourite authors aboard the magic carpet: we were delighted by the enthusiasm with which they accepted. Spread the Word also hopped on to help us find our fifteen surfacing storytellers.

The call out in May 2020 was heralded by the anthem, PERMISSION, written and recorded for us by our long-time musical collaborator, Andrew M Pisanu of Memory Flowers. We had over 150 entries, read diligently by our team: Aliya Gulamani, Alex Hopkins, Angelica Curzi, Keith McDonnell—thank you. From their feedback, we selected a longlist, then it was handbags at dawn between Justin and Nathan for the final selection. Only joking: our choices emerged naturally, amicably. Though there were certainly some brilliant stories to which we were sorry to say goodbye.

Mainstream is our most ambitious project to date and—because of the collective nature of the book—it felt right to crowdfund it. We teamed up with Unbound, reaching our minimum target in October 2020: this meant we could cover the print run, and pay our writers for their contribution. To all those who got behind the campaign, we cannot thank you enough for pledging.

Then the fun bit: editing, production! What a pleasure it’s been working with this panoply of talent, and further thanks to Lisa Goodrum for her exacting proofreading.

So, here we are, two years on and our anthology is finally a thing. Mainstream really has been a labour of love: we hope you take it to your hearts as much as we have ours.

––––––––

Justin David & Nathan Evans

Inkandescent

HOME TIME

Kathy Hoyle

––––––––

When we walked through Gypsy Tony’s fields this morning, the horses were swishing their manes in the wind. They always do that when it’s cold. Dad says that north wind comes straight from Iceland. I wish I could have jumped onto Bert, or even Nippy and let one of them carry me home to a bowl of soup from Mam’s big pot. I’m stuck here with our Kelly instead. The boring beck. There are no other kids here today; most of them stay in their back yards these days. There’s all kinds of carry on in the village. Mam says we’re not to talk to anyone. I don’t really know what we’re not supposed to talk about, just that I’ve to keep me gob shut.

It’s Mam’s fault I’m stuck here freezing to death. She shoved us into our coats first thing this morning, gave us a carrier bag of jam sandwiches and a bottle of orange juice and told us to bugger off till tea time.

It takes ages to get here. It’s way past the park and the slag heaps, but Kelly says it’s the best place to catch the taddies. There’s no fish in the beck. Kelly says the shit-pipe from the mine runs into it, so no fish live. There’s nowt except the tadpoles and loads of green moss. If we catch them and get them into the wooden crate, we can hide them in the coalhouse and then we’ll have frogs. First, we’ve got to catch them.

We’ve been at it for flipping ages. The bottom of my jeans are soaked—fill the jar, pour the jar, fill again—like little kids in playschool. I’ve only found three tadpoles all day. I can’t wait till I’m older. Then I’ll get to say where we play, instead of Kelly. Sometimes she thinks she’s me mam. She thinks she knows everything ’cos she’s twelve now and I’m only eight.

‘We’ve been out ages.’

––––––––

I’m not supposed to whine ‘cos Kelly will clip me, but I can’t help it.

I dunno why we can’t stay in on cold days. Me mam says kids should still play, even with what’s going on with the bobbies and the pickets ’n’ stuff. She says at least fresh air’s free ‘cos that’s all we can afford nowadays. Me nanna says she’s full of shite and that they’re buckled now Dad’s got a new job. Mam says I have to keep me gob shut about that. Everyone else goes to the welfare club for soup and sandwiches but we still go to Fine Fare for our shopping.

I wipe my nose with the sleeve of my anorak then stuff my hands into my pockets. I hop from welly to welly watching Kelly pulling green streaks of moss from the jam jar. She shakes the jar then tips it and smacks the bottom with her palm. A wriggling tadpole falls into the crate. She’s caught loads. I pick up a stick from the bankside and crouch beside her, swirling the creatures and the moss around. I spell-cast. The potion should be drunk by my enemies, like that Robert Gooding from third year who spat on my back and called me scab bitch or Charlotte Dawson’s mam, who never lets her come for tea at mine and looks at me like something the dog shit out.

Kelly digs me with her elbow. I drop the stick and stand up, brushing the hair out of my face.

‘Mam said don’t come home till tea time. Did you not hear?’ Kelly checks the pink watch she got for her birthday, ‘It’s only half three.’

‘Howay, Kelly,’ I say, ‘Mam always says tea time. I’m freezing. We can play Sindys. You can have the car this time.’

Kelly stands up and wipes her hands down her jeans, leaving streaks of moss on her legs. Mam’ll kill her. She only just got them jeans from the catalogue. She smiles. I hardly ever let Kelly play with my Sindy car.

‘We’ll put these back first,’ she says, nodding towards the crate, ‘they’ll probablys need their mams, or they’ll die.’

‘Leave them. They’ll be alright. If the mams are owt like ours, they’ll be glad to get rid.’

Kelly tuts.

‘Don’t be daft. She only wants us out so she can get on. She’s got to see to nanna and go down the welfare club to give the strikers their dinners.’

‘She hasn’t been down the club for ages.’

Kelly’s cheeks go red.

‘Shut up, she does her bit.’

‘I’m only saying what Nanna said.’

Kelly picks up the crate and flings the whole lot into the beck. I thought she might bring a few back in the jar but she’s gone in a right moody now.

‘Howay,’ Kelly says, yanking my hood, ‘we’ll walk slow. And don’t blame me if she goes off it.’

We walk along the stone path at the side of Tony’s field, stopping to pat the horses on the way. We feed Nippy crusts from the jam sandwiches in our carrier bag, even though we know he’ll take a finger off given half the chance. Kelly gives him a cuff on the nose before walking off. My welly digs into the heel of my foot and I pull it off, taking me sock with it. Kelly stamps her feet against the wind while I prod at a blister on the back of my heel.

‘Hurry up,’ she shouts. My belly flips. I don’t want her to go without me. I still don’t know all the way home on my own.

I wince as I put my sock and welly on. I try to be dead quick and end up losing my balance, falling on my backside. I swear, under my breath. Last time I swore, Mam nearly took the side of my head off. I’ve trained myself to say the F words and the S words only on the inside of my mouth. Kelly huffs her way back to me. She pulls me up and yanks the sides of my coat together then zips me in. She takes a tissue from under the cuff of her coat.

‘Wipe yer bloody snoz,’ she says, curling her lip.

I hold my hand out for the tissue, but she wipes it instead and gives me a sharp punch on the top of my arm before we set off again.

Finally, we get to our back gate. My legs are aching and my blister is stinging like mad. I need the plasters from the biscuit tin in the top cupboard. I’ll ask Kelly to get them. Last time, I knocked Dad’s whiskey down by accident. Mam slapped the back of my legs with a slipper and said, ‘how the fuck’s he gonna sleep now?’

Mam and Dad have been weird since the strikes. Nanna says that bastard Thatcher’s got a lot to answer for. I asked if I could come and live with her until the strikes are finished and me mam and dad stopped shouting. She gave me a cuddle but she never said yes. I think it’s ‘cos her legs are bad. She probably wouldn’t be able to look after a little kid. Me mam has to take her dinners round.

Mind you, she moved pretty quick when the bobbies were taking Eileen’s husband, Jimmy last week. Her and Eileen were shouting ‘bastards’ and hitting them with rolling pins. Eileen had to stay at me nanna’s after. I made three pots of tea—I’m dead careful with the teapot—but Eileen still didn’t stop crying. In the end I got fed up and watched the racing with Grandad. Me and Grandad shouted at the telly for a treble up but never won owt. He says he’s the unluckiest bastard on earth.

––––––––

Kelly says it’s Dad’s fault for getting a new job and shitting on his mates. I asked Dad about it the other night. I woke up after Kelly had made me watch Thriller again. Dad was on the landing. Me and him crept downstairs into the kitchen. I sat on his lap for a bit. We don’t normally do that ‘cos Kelly laughs at me and calls me a baby, but she was in bed, so it was safe.

‘Can you not sleep, bairn?’ he asked.

‘Nah, Michael Jackson’s gonna get me.’

‘Nowt bad’s gonna get you, pet,’ he said, stroking my hair.

I asked him then.

‘Dad, are you bad?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, Robert Gooding says you’re a bastard ... and a scab.’

Dad gripped me by both arms, hurting a bit.

‘Listen to me, Pet. I do what’s best for you all. Even if that means doing something other people don’t like. I’ve never crossed a picket line. EVER!’

I jumped a bit when he shouted.

‘I got a new job that’s all. Just, the timing was shit and ...’

He let out a long breath, ‘I’m not bad.’

I cuddled into him. He smelt of soap and whiskey and I believed him.

I push open the gate and limp up the path towards the smell of minced beef pie. My mam’s dead good at baking. Me and Kelly tumble through the back door into the outhouse. ‘Me first,’ says Kelly, elbowing me out of the way to get to the downstairs toilet—‘the posh lavvy’ me mam calls it. I pull my wellies off and throw them at the shoe rack then take my coat off and reach up to hang it over the top of Dad’s anorak on the coat pegs.

I push open the door to the kitchen. Uncle Gary is sitting on a chair at the kitchen table ... again. His legs are stretched out in front of him, and he’s holding up the paper. There’s a black and white picture of Jimmy and the policemen on the front. You can see Eileen pulling the policeman’s arm, snot and tears all over her face. Nanna’s rolling pin is in the top corner of the picture.

Gary puts the paper down just as I’m trying to get a better look. He’s got his work boots on and his donkey jacket. It’s been two months now since any dads went to work. But he still wears his stupid jacket and his stupid boots.

‘Alright, kidda,’ he says, like he’s my friend.

I used to think he was my real uncle till Kelly told me he wasn’t. I used to like him, when he came round with Auntie Linda and Debbie. I loved Debbie. She’s older like Kelly, but kind. She always played hairdressers with me and let me do plaits in her hair. They never come round now. Just Gary. He calls me mam pet and love. I think only dads should call mams pet and love.

Mam has her back to me. She’s fiddling with something in front of her, but I can’t quite see. She turns and scowls.

‘Why’re you two back? I said tea time.’

‘We were freezing,’ I say, and walk over to the steaming pie on the counter. Mam taps my hand as I reach out to it. The buttons on her blouse are all done up wrong. I can see the white lacey bit on her bra poking through the gap. She catches me looking and turns away quickly. I feel something squirm in my belly. I don’t feel hungry anymore.

‘I need a plaster, Mam,’ I say but she’s fussing with the pie. Cutting a big slice off and wrapping it in tin foil.

‘I’ll best be off, love,’ says Uncle Gary. Mam hands him the foil package.

‘Will you bring Debbie next time?’ I ask.

‘Aye, maybe.’

‘I’ll see you out, Gaz,’ she says. It’s Gaz now.

He stands up and leans towards me. I notice a pink smear of lipstick on his chin. It’s the same shade as Mam’s.

‘Tarra bairn,’ he says.

I turn away as he goes to kiss my cheek.

‘Bring Debbie next time,’ I say.

Kelly comes through the door.

‘Get in! Pie for tea.’ She goes to the pie and sniffs it.

Mam smiles at Kelly, a pretend smile, all stretched and thin-lipped.

‘Hold on. I’ll just see Gary out.’

Mam and Gary go through to the front passage, closing the door behind them. I can hear them giggling.

I feel a sharp push in my back.

‘Howay then, Sindys,’ Kelly says.

‘Will you get me a plaster first?’ I ask and Kelly rolls her eyes. She climbs up on the worktop, opens the cupboard and pulls out the biscuit tin with the plasters in.

‘Pick one then,’ she says. I choose a Mr. Bump plaster. I stick it to the back of my heel. No accidents this time.

Me and Kelly go to our bedroom. We pull out the Sindy box from under my bed and Kelly starts making the house. I take the pink car out and wheel it over to her.

Sindy is naked, showing off her bare boobs and long slim legs. I put a small flowered skirt on her. I pick up a boy doll. He’s naked too. He has a smooth surface where I know a penis should be. I have boy cousins. I put him in blue trousers and a brown waistcoat.

I squidge their faces against one another.

‘Oooh, Gary, I love you,’ I sing song, in my ‘American’ voice.

‘Oh, Denise, I love you too,’ the boy doll replies.

I make them kiss.

Kelly grabs my hands and pushes them and the dolls down hard into the carpet.

‘Ow!’ I say, trying to pull away.

She glares at me and won’t let go.

‘Don’t you dare tell Dad,’ she hisses.

‘What?’ I’m scared of Kelly when she’s like this.

‘You don’t tell Dad that Gary comes round. Right?’

I nod. Sindy’s plastic hands are digging into my palms like sharp pins.

‘And don’t be telling Nanna either.’

Stupid baby tears come.

Kelly lets go and I breath out.

I throw the dolls down and look at the bright red marks on my palms.

‘Sorry,’ Kelly says in her kind voice, ‘It’s just, Dad and Gary will fall out, and Mam’ll be in big trouble.’

I wonder if that might be good. Maybe Dad will have a fight with Gary. Punch him, like Robert Gooding punched me, in the belly, so hard that I puked into my own mouth and had to spit the mush onto the grass. Maybe the bobbies will take Gary away, like they took Jimmy, then Auntie Linda can come to ours and cry like Eileen, and mam will make her a cup of tea and they’ll be friends again. Maybe Dad will stop drinking whiskey and shouting at Mam. And maybe Mam will stop sending me outside in the cold, or to Nanna’s or to anywhere that’s not home. Maybe I shouldn’t keep my gob shut after all.

GIANT

Lui Sit

––––––––

The year I turned nine I rode to school for the first time on my own. The quickest way was through the dirt path in the forest that began at the end of our street, but Mum had warned me never to ride down there by myself.

‘It’s completely hidden from view Simon,’ she said. ‘If anything happened to you, no-one would know so make sure you take the main road.’

But one day I turned towards the dirt path, not away, and from then on, that’s the way I went.

The first few times I was so relieved to make it safely to school that I didn’t look at anything apart from the path ahead, but soon, I took in the surroundings more. The tree branches arching above formed a dense canopy, allowing only shallow streams of light to filter through. The woods smelled of damp earth and the sound of birds calling to each other overhead, reminded me that I was alone and no-one knew where I was.

––––––––

On that day, I was close to the turning at the end of the path which led back out to the main road. As I approached, I turned my head to the left and nodded goodbye to the trees, a gesture I’d repeated each time to keep me safe on the journey which had now become superstition. And that’s when I saw it, a strange mound to the left of the track in a small clearing where no trees grew. It looked as if a giant anthill had erupted from the ground overnight, so I stopped and wheeled my bike over. Up close, I could see the mound was not made of earth but a slick, dark ceramic, except that it wasn’t ceramic because it was pulsing, like there was a heartbeat or a pair of lungs inside.

I dropped my bike, inching closer. The air around started to smell of burning and all of a sudden, the urge to touch it was overwhelming. Nothing around me was moving, no insects, no birds and even the rustle of the wind in the thin undergrowth had stopped. I reached out my hand and heard Mum’s voice screaming, No, but my hand met the surface and then, instead of being in the forest on my way to school, I was standing on the face of a giant, his breath hot against me and my hand clutching his nose which was damp and dimpled with pit marks. His eyelids started to open, revealing two bright green pupils, scanning upwards like a pair of spotlights. I pulled my hand away and as I did, the face started to dissolve, the ceramic surface turning into grains of fine, black sand which swirled into the ground, a vortex beneath sucking everything down.

I stumbled backwards, watching the giant’s eyes turn from green to charcoal before disappearing altogether. The ground was flat and earthen, as if it had never been disturbed and whatever that was, the giant, the anthill, the moist, dark mound was gone. I felt the wind return and heard the noise of birds squawking overhead. Flexing my hand, I hoisted my bike upright and pedalled fast for school.

––––––––

That night, Mum closed the book on her lap.

‘What did you think of the ending?’ she asked.

I shrugged, my hands picking at the duvet.

‘Not a fan?’ Ok, well you choose the story tomorrow.’ She kissed my forehead and smoothed back my hair before standing up.

‘Mum?’

She looked back, her brown fringe swinging into her glasses.

‘Do you believe in magic?’

Her eyes clouded over.

‘Well,’ she started, ‘I know you do, don’t you? Everyone says you have a gifted imagination.’

She paused before continuing.

‘Did something happen?’

When I didn’t reply her lips creased into a smile that didn’t reach her eyes.

‘It’s ok Simon. You know you can tell me.’

So I did. I watched a tightness pan across her cheeks when I got to the bit about the dark mound and how it had turned into a giant’s face, but it didn’t stop me from telling her everything, right up to the point where the sand had drained back into the ground and even though that was all there was to tell, I wanted to say more.

‘Simon. Stop.’ She touched my face, her palm sweaty.

‘Do you believe me Mum?’

She sighed and wedged the copy of The Little Prince under her arm. We’d just read a story about an alien who talked to a flower. She had to believe me.

‘Go to sleep, we can talk more about it tomorrow.’ She switched off the light and closed the door, turning the room dark. I pulled the duvet high up over my shoulders, burying myself beneath its weight. I didn’t know what else to do but close my eyes and try to go to sleep.

––––––––

I’m at the bottom of a waterfall. Water is cascading down around me, streaming past either side of my body into the swirling, green pool below. I look down to see my bare feet standing on cold, flat rock. Despite all the water, I’m not wet, my blue flannel pyjamas are dry and warm. I reach out to touch the water but it rejects my hand as if it were a magnet, repelling with equal force. Raising my arm above my head, the flow of water moves with it, as if I’m lifting a curtain. I raise my other hand and the same thing happens. I laugh and wave both hands in the air, the water moving in equal rhythm. This is brilliant! Bringing both arms high above my head causes the water to part, revealing a cave behind the waterfall where a face stares out at me. He’s solid again, his whole head etched from the length and breadth of the cave rock. His black granite features seem to have grown outwards from the rock, just as he’d grown out of the forest floor. Gagging, I try to drop my arms but they remained pinned in mid-air. The giant smiles, the dark rock grinding into formation but there is no friendliness in his green stare.

‘Simon?’

‘Mum?’

I look around but I can’t see where the voice is coming from. There’s just water, ebony rock and the face ahead.

‘Mum?’ I shout, my arms tingling from pins and needles.

The giant’s smile widens showing a mouth full of grimy, jagged teeth. Except one. One tooth is pale and wriggling because it isn’t a tooth, it’s a person, wedged between the lower canine and incisor. A person wearing glasses in a long nightgown with brown hair falling down onto her shoulders and into her eyes.

‘Mum! My scream bombs through my head just as the giant snaps his mouth shut and my arms flop down, closing the curtain of water. My legs give way and I topple headlong into the swirling pool below.

––––––––

‘Mum!’ I was sitting bolt upright in bed, my pyjamas drenched with sweat. I flung the duvet off and ran out of my room onto the landing where I could see Mum’s bedroom door shut tight. I pushed down onto the door handle and stepped inside. On her bed, I could see the cushions neatly arranged, propped up against the headboard and the smooth, flat quilt with no body beneath. It looked like no-one had been in it at all that night. Where was she?

I nearly slipped scrambling downstairs, the wooden staircase treacherous against my bare feet. Reaching the hallway, I fumbled for the light switch but nothing happened. I flicked again, but darkness remained. Racing through the house, I tried the kitchen next and then the front room, but no lights worked.

The stillness of the hour started to press on me and I could feel my panic bursting to get out. I needed to pee too. Entering the bathroom, the battery-powered cabinet light was on, the mirrored doors open wide, highlighting the toiletries and medicines inside. As I emptied my bladder, I scanned the cabinet shelves, wondering what Mum had been looking for and if she was unwell. The thought made me shiver in my damp pyjamas as I returned to the kitchen, pulling open the drawer where Mum kept the matches and torch.

‘Please work,’ I thought as my hand grasped the torch handle. Pressing down, the space flooded with light, the kitchen clock illuminated at 11:45pm confirming that Mum had left me alone, late at night.

My legs bolted towards the front door which I was tall enough to reach and unlock from the inside. Stepping out, the night chill hit me. The streetlamps were on showing how still and quiet the street was apart from a few neighbourhood cats trotting across the road. Our garage shed door was wide open, the car gone.

I padded across the dew-soaked lawn towards Mrs Wilton’s house next door. She said that old people didn’t need as much sleep as the young which made me think she mustn’t sleep at all as she looked ancient. She often looked after me when Mum was working and I knew that out of all the neighbours, she would be the least angry at being woken up. I only had to knock twice for her to appear in the doorway in a faded green robe, her hair in curlers.

‘Simon,’ she croaked, ‘What are you doing here?’ Her lined face seem to have grown a few more etches since I last saw her.

‘Mum’s gone.’

‘Mum’s gone?’ she parroted, confusion creasing her sleep-worn face.

‘I woke up and she’s not here. The car’s gone too.’

‘Heavens,’ she clucked and scooped me in, crushing my face against the folds of her musty robe. ‘Come in. Whatever was she thinking?’

She hustled me into the kitchen, turning on the lights before going to fill the kettle. The warmth in the house started to seep through and I felt a swell of exhaustion break over me as I slumped down into a chair by the dining table.

‘Are you hungry my love? Piece of toast?’ Mrs Wilton was looking at me like I was an abandoned cat she’d found on the street. She often looked at me like that. I nodded.

‘Yes please.’

––––––––

As she opened the bread bin I wandered to her front room window. The heavy damask curtains were drawn open, showing the street outside that I’d just come in from.

As I stared, the air outside started to shimmer, as if a heatwave had descended onto the street. Undulating and wavering, this air started to form a shape all too familiar.

No. Not again.

The giant’s face was formed now. I could see his wide features. The hooded eyelids and sharp rise of cheekbone against the broad, angular jaw. The flat nose broadened further as his nostrils flared, inhaling deeply all the air that I had stopped breathing. The head turned to face me and started to move towards the window.

A noise roared out of me as sweat trickled from my scalp onto my face. My chest felt like it was hosting a family of hyperactive mice, heaving and twitching like there was something living inside. I rubbed my eyes with my fists but the giant’s face was still there when I looked again. My mouth pooled with saliva as the giant’s lips opened and I saw that all his teeth were gone, the gums fleshy and horribly pink and its tongue looked like a patchwork of swollen slugs.

I squinted my eyes to slits but it didn’t stop the massive jaw from craning wider and wider. I pressed myself right up against the window, wanting it to protect me and also let me see everything. My hot breath misted over the glass, smudging when I wiped it with my hand. Suddenly, the air stilled as the giant’s mouth stopped opening, frozen into a wide gape as if it wanted to swallow Mrs Wilton’s house. The thought sent a bolt of fury through me.

‘Go away,’ I shouted. ‘Stop following me.’

I looked around for something, anything that I could hurtle through the window, smashing the glass to send away that ugly face. My hand found the neck of Mrs Wilton’s antique brass table lamp. I lifted it above my head, its velvet green tassels dangling in my face and the heavy weight of it making me stumble but before I could throw it, I saw him.

A small boy, young, with tufts of dark hair sticking out from his head climbing out of that infernal mouth. He was dressed in pyjamas with bare feet. He turned in my direction and it was me, my legs wide apart, my hands holding a table lamp with green tassels which I brandished above my head like a trophy, and the shock of seeing me made the lamp slip from my grasp, the glass bulb exploding onto the ground, shattering shards of glass everywhere.

‘Simon.’

––––––––

Turning, I saw Mrs Wilton, a plate of toast in one hand and a glass of water in the other. Standing next to her was Mum, in blue jeans and her old brown jumper, her handbag slung over her shoulder. She held out her hand, guiding me around the broken glass into the warm kitchen, Mrs Wilton following behind.

‘Sit down.’

Mum pulled out a dining chair and patted the seat, as if it were normal to be in our neighbour’s kitchen at midnight.

I gulped, my mouth filling up with saliva.

‘Mum,’ I retched, choking down the spit. ‘He’s out there.’

I pointed outside but she and Mrs Wilton just kept staring at me.

‘Me too,’ I gasped, ‘I’m out there too.’

Mum reached into her handbag and pulled out a small packet, the label reading Parron’s 24-Hour Pharmacy. Seeing that familiar logo in dark red drenched me in a wave of cold sweat.

‘No Mum. I don’t want to.’

She popped two yellow capsules out from the aluminium seal and nodded at Mrs Wilton who handed her the glass of water.

‘Come on Simon. We’ve talked about this.’

She held the pills out to me but I turned my head away at Mrs Wilton who smiled sadly. Mum grabbed my jaw with her free hand and pried my mouth open.

‘Swallow,’ she urged, ‘we only have a short window before it’s too late.

She shoved the pills into my mouth and some age-old reflex took over as I swallowed them down dry. Pulling me into a hug, I could feel her heartbeat thundering just as urgently as mine.

‘I’m sorry,’ she murmured. I looked up at her and saw how tired she was.

‘But he’s out there,’ I repeated, peeling my lips apart. The saliva was gone, replaced by a desert. She stroked my hair and tilted my head back so she could see my eyes.

‘I believe you,’ she whispered. ‘I believe you.’

IN THE SHELL MUSEUM

Padrika Tarrant

––––––––

Limpet; nautilus; Devil’s toe. The shell museum is where we wait for the end of the world, like broken glass that dulls in the tide. We have the great huge sea in our lungs. We have sand in every crease and pore. We blink and blink but our eyes are crusted with it and we can barely see.

You still have one of your flip flops, sodden and mouldering. The pink and blue are faded white. Your other foot’s bare and crinkled. We stand in puddles all the time; we keep warm as best we can, but our clothes are ruined and there isn’t much to live on in the shell museum. When the attendant isn’t looking, we steal squares of fudge and t-shirts which say I have been to Great Yarmouth. We wear them in layers; the salt always weeps through.

Lion’s paw; moonshell; pink coral. The shell museum is huddled around us; your fingers are embalmed, and your nails are ever so long. You clutch your peg-doll; her face has worn away now, but we say she looks just like Mama. Your hair is a tangle that nothing could tease through, not even razor shell, or the pretty combs sold by the promenade. They used to sell spades, sunglasses, little buckets embossed with starfish too. I expect they still do.

Magpie shell; sand dollar; periwinkle. The shell museum is riddled with artefacts, laid out in finicky little boxes like jewellery, waiting to be seen. If visitors come by, they turn the lights on for them. But they don’t come and all there is to squint by is the threadbare slant of air from the window.

I hold your hand, seeing as I am the eldest, and we cling together as if to keep one another safe. It is a long time since either of us were safe. I sing quietly when we are alone, nursery rhymes from before. Or else we gaze at the exhibits, tracing the labels of this or that shell, peering at the tiny writing: Genus (with a capital letter) and species (with a small one). You like the seahorses best. You don’t understand that they are dead.

One time, another child did come in out of the rain. She was so wet; she stopped right in front of us with her lips moving as if she was remembering poetry. She stared right through me for a minute or more, and I thought, I really thought, that she could see me. She walked away.

Measled cowrie; slipper snail; zebra ark. The shell museum is our home. We crept here very long ago. No-one would ever notice us, if it weren’t for the creak of the ocean when one holds us to their ear.

EASY PEELERS

Lisa Goldman

––––––––

Eat Up, Mrs Knowles says. Eat it all up now.

No.

Don’t you know how lucky you are?

*

Mama juggles the Easy Peelers—two, then three, four, then five—orange suns jumping round my head. I’m choking with laughter at something Mama says. We’re in what Mrs Knowles calls the Dark Times when the sun was always shining. Before the Big Green King. When Mama juggled for crowds in clown face. Juggled plates and oranges, burning sticks. Swallowed fire.

I don’t like clown face, Mama.

I put it on, Innochka, so I can save my real smiles for you.

I’m lying in the festival field, Earth’s drum humming through my body. Mama and her new boyfriend Raoul practise juggling. Raoul’s a lousy catch. He drops an Easy Peeler. Its thick shiny skin tears easily.

Clumsy! I laugh at him.

Must of hit a stone, Raoul says.

But it isn’t, it’s a shard of china, a chip from an old plate. Pierced puckered skin leaks bittersweet juice. Raoul digs fat fingers inside the wound and pops the fruit from its orange jumpsuit.

See, he says to Mama, I told you Easy Peelers are too soft.

Raoul splits the flesh with his giant hand. Three injured bits for him. Two nice bits for me. Raoul feeds Mama the perfect three.

I watch juice dribble down her chin. I’m glad she peeled off clown face—the orange tastes better from her skin.

Greedy, Raoul says to me.

Mama smiles.

*

One day at school, Yaz—who everyone wants as a friend—calls me an Easy Peeler when Mrs Knowles is watching. I’m hot and frozen to the spot. Yaz’s eyes flick over me.

Back home I ask Mama what Yaz meant by Easy Peeler.

We don’t use those words about people, Mama says.

Why not, Mama?

Because no one can help being poor.

After that, I hear it all the time, chat about Easy Peelers.

Too many of them—they’ve bred out of control.

Didn’t buy at the right time. Couldn’t buy, to be fair. Now they’re out of the game.

Just staring.

Squatted two flats on our block last week.

With Easy Peelers living there, things’ll go bad fast!

Why do we even need them there just staring at us?

*

I’m collecting with school for the Big Green Clean Up.

The old man smells of wee and his thin coat is torn, but he thrusts a shiny coin into my palm. This is for you not the fucking Clean Up. Buy yourself some food, you poor little Peeler.

Peeler again. My fingers turn the golden coin. I could buy Mama an orange and watch the juice dribble down her chin. Oranges are hard to get these days, nowhere down the market, but I’ve seen some plump and dimpled in a shop we never stop at. If I buy Mama an orange, she’ll smile, say something sweet in Russian.

I call her Mum or Mummy now in front of strangers. The only time I hear her speaking Russian is in her sleep.

The gold coin is hot and heavy.

Yaz says Clean Up money is to fight the Green King’s enemies. What if the old man is an enemy? If I keep his money, does that make me an enemy too?

No. The old man stank but his eyes were kind. Perhaps he was just testing my loyalty to the King.

I weigh up this loyalty now against buying Mama an orange.

When Raoul was still alive, I’d catch him staring at my Big Green Clean Up badge. I worried that he might think I loved the King more than him, which wasn’t true. Though I did see more of the King, what with his face being everywhere. And after scary May Day when Raoul got shot in the Square and my coat couldn’t stop the blood and Mama lost her job and stayed in bed just sobbing, I started talking to the King.

Please Green King, let Mama’s voice come back. Let me find enough money to buy her an orange so I can lick the juice that dribbles down her chin. If you make this happen, King, I’ll sacrifice everything for your Big Green Clean Up.

Making sacrifices is a big theme at school.

Inna, what did that Easy Peeler say to you? He’s sent you into one of your little dreams. Mrs Knowles is as close now as the old man was when he gave me the coin. I look up at my teacher’s round, smiling face.

Miss, I ask. What’s more important do you think? Making Mummy happy or making the Green King happy?

Mrs Knowles’ eyes flash and the world goes dark.

Why would you think those two things different, Inna?

My tummy flip-flops with fear.

What has Mummy said about our King? You know you can tell me everything. Mrs Knowles’ voice sounds pulpy and sweet.

I spit it out like an unexpected pip: Mummy doesn’t talk since the May Day Massacre.

You mean the London Riots?

I just want to make her happy, Miss.

Mrs Knowles ruffles my hair. But what on earth does all this have to do with our beloved King?

I’ve got a gold coin, Miss, and I don’t know what to do. Should I donate it to the Clean Up or buy an orange for Mum?

Now it’s all out in the open and whatever the answer, already I feel better.

Mrs Knowles’ eyes are moist as her finger twirls my hair, the same colour and style as her own, though Yaz said Mrs Knowles gets hers out of a bottle.

Don’t you think Mummy would be proud if you sacrificed your gold coin to the Clean Up? Mrs Knowles’ lower lip trembles. If I was your Mummy, I’d be very proud indeed.

I stare up at my teacher. All is clear.

I push my sweaty coin into the donation tin. My heart swells like our special Crow Song.

I beam across at the other girls and boys busy stopping strangers. I am the greenest, cleanest of them all in the Big Green Clean Up—closest to our King. He’s watching me sacrifice everything and there will be more sacrifices now, so many more. I can’t wait!

When I step into the path of the next passer-by and ask Do you want our streets to be safe? I feel as if I own the streets, as if the King’s arms are wrapped around me like a thick, warm coat.

*

Back in class, Mrs Knowles tells everyone what I did.

It’s not where you start in life, she says.