Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: The Prime Ministers

- Sprache: Englisch

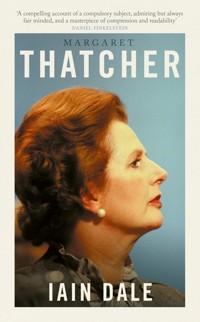

'A compelling account of a compulsory subject ... A masterpiece of compression and readability' Daniel Finkelstein 'A deft, clear-eyed summary of Thatcher's life' Rory Stewart 'Iain Dale introduces Margaret Thatcher to a new generation and intelligently explodes some of the myths about her' Simon Heffer Margaret Thatcher was a woman of tremendous paradoxes: a conviction politician who was also a pragmatist; someone who delighted in her tough reputation, yet could also be emotional, and even tearful, when confronted by personal or national tragedy. Her reputation as a cabinet leader was one of being quasi-dictatorial, yet she left her ministers to get on with their jobs – far more than any of her successors ever have. She was known as a classical laissez faire liberal, yet she started out as a social conservative, and wasn't averse to state intervention when she felt it was warranted. Iain Dale's sparkling short biography of Margaret Thatcher brings her to life in all her paradoxes and contradictions, and shows how her election in 1979 really was a turning point in British history. Dubbed the 'Iron Lady' by the Soviets, she was one of the few recent prime ministers to burnish an international reputation, fighting the Falklands war, playing a leading role in defeating Communism and winning the Cold War, and through her battles with the European Economic Community. Domestically, she ushered in a period of forty years of consensus on the limited role of the state, an industrial relations settlement and the dominance of the private sector in the economy – a settlement that is only now being seriously questioned. A little over a decade after her death, Margaret Thatcher introduces her to new generations of readers who may not remember her premiership, but who are living with its consequences.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 224

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Iain Dale

Memories of Margaret ThatcherMemories of the FalklandsThe Margaret Thatcher Book of QuotationsMargaret Thatcher In Her Own WordsAs I Said to DenisThe Prime MinistersThe PresidentsKings and QueensThe DictatorsThe GeneralsThe TaoiseachBritish By-ElectionsBritish General Election Campaigns 1830–2019The Honourable LadiesWhy Can’t We All Just Get Along

For my god-daughterZoe Dale-Webb

Contents

Foreword by the Rt Hon. Penny MordauntIntroduction1 · The Making of a Politician, 1925–59 2 · Climbing the Greasy Pole 3 · Winning the Leadership 4 · Leader of the Opposition 5 · Goodbye Keynes, Hello Friedman 6 · Reforming the Trade Unions 7 · Northern Ireland 8 · Victory in the Falklands 9 · Foreign and Commonwealth 10 · Reagan and Gorbachev 11 · Europe 12 · Downfall 13 · After Downing Street 14 · Success and Failure 15 · Twelve Myths Acknowledgements and Further ReadingForeword

During the election campaign of 2001, as we prepared for a rally to support William Hague, we were told to expect a surprise guest. There was much excitement as party members gathered in breezy Plymouth. Photographers and lobby scribblers assembled. A police-escorted car rolled up. She got out. To the whir of camera shutters, she slowly, purposefully scanned the assembled throng. ‘Not you lot again,’ she protested.

They loved it. They were glad to see her. They understood her code: it is good to be back, you are all rotters, but I have missed you. I know you have missed me too.

Later she was to jest on stage that she had been assured her visit was top secret, yet when she had arrived in Plymouth town centre she was shocked to see her presence advertised on the front of every cinema: The Mummy Returns.

She knew her reputation. Terrifying and reassuring in equal measure.

In her speeches and all my interactions with her she demonstrated a keen sense of humour and impeccable timing. That requires a person to have empathy. She could put herself in the shoes of others. She understood their hopes and frustrations. She could connect. She was able to narrate theirs, and the national story.

I believe she also saw it as her job to keep us all going. The nation. The party. And us as individuals. Her recognition of the courage and sacrifice of those who stepped up to take responsibility, whether it was a business owner, our services and armed forces, families doing their very best for the next generation or human rights defenders, motivated people. She got us to believe in the right of our cause and our agency to have effect, as a country and as individuals. She admired that quality in others.

Her eulogy to President Reagan noted that the arduous missions he set himself

were pursued with almost a lightness of spirit, for Ronald Reagan also embodied another great cause, what Arnold Bennett once called ‘the great cause of cheering us all up’. His policies had a freshness and optimism that won converts from every class and every nation, and ultimately from the very heart of the evil empire.

Her repartee was less obvious than Reagan’s – she never started a speech, ‘Did you hear the one about…’ – but humour was an essential part of her armoury.

She was from an age where politicians were able to say less. But even if she were here, in the age of constant social commentary, I think she would have chosen to say less, better. I remember in the green room at party conference her complimenting another’s speech. ‘There was not a superfluous word in it.’ She did not waste words. She understood they did not just need to explain. They needed to move people. Mood mattered. Mood moved markets. Mood inspired people to take responsibility. Her vocabulary was aimed at head and heart.

I think she also knew the necessity of encouragement. She had undoubtedly faced huge obstacles through her career, but she had been blessed with people, family, friends and colleagues who gave her support. She was generous in this regard to others. Especially those, I believe, who were the outsiders. Women and men who had fought their way there. That is how she was with me. She was frequently present at meetings to encourage and support candidates. And she wrote to us. I treasure two letters in particular. One was when I won my seat in 2010. The other was five years prior, when I had first run and failed to get in. You must keep going; we need you to work hard and it will come good, was her message to me.

The image sometimes painted of her of being unthinking about others’ feelings does not square with what I knew of her. The late Sir Tim Bell, who had been her ad man, told me she was the only one of her political generation who didn’t ‘treat him like trade’. She’d have him round for supper. She was grateful for his time and expertise. They were equals. No one else made him feel that way.

The bond that she created between herself and so many of our countrymen – whether directly or indirectly – was powerful. It lasts today. This was brought home to me powerfully in the 2017 election campaign, at an event also taking place in Plymouth – the San Carlos dinner. This was the annual get-together of those who took part in the Falklands task force, and they had asked me to address them. All present had been deeply affected by the war, and not just those who had worn a uniform. The chap who was playing the piano that night had been the cruise liner Canberra’s pianist and recalled his emotions during that time as she and her crew were taken up from trade to help the war effort. I knew speaking to these men and women about the campaign would not suffice. I’d been nine years old during the war. What on earth could I tell them about it? So I asked my local newspaper to help. We found in their archives a letter Thatcher had written to the people of my home city, Plymouth’s sister port of Portsmouth.

My speech was her short letter. And it was all that was required. It was the confirmation they needed. All wept with deep pride.

She is no longer with us but her ability to move us, and connect people together, through her words and deeds remains. She said of Reagan that for those that followed him their task would be easier, because we had his example to follow. Her example to us was not just in what she believed but in how she fought and argued for it.

Politics recently has been about coalition-building through patronage and deal-making. Her politics did not rely on that. It was about winning people over through pragmatic, competent service, fearless conviction, arguments that reached across the divide, but most of all by lifting our spirits.

Penny MordauntPortsmouth, November 2024

Introduction

If you’ve read Charles Moore’s magisterial and brilliantly written three-volume account of Margaret Thatcher’s life, I’m tempted to advise you to stop here. This short biography is not for you.

If, on the other hand, you are like my personal trainer, Aaron Fowle, then you should read on. I had broken my hip and had gone to my local gym in Tunbridge Wells for some physiotherapy. Part of this was a weekly session with Aaron. He asked me what I did for a living, so I told him I presented a news and politics show on LBC radio each evening. Aaron then said: ‘So Margaret Thatcher… I’ve heard of her, but who was she? What did she do?’ Aaron was twenty-five at the time. He’s an intelligent guy, so I said I’d write this book for people like him who weren’t adults when Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister. People like an Italian friend of mine, Alessio, who is a keen young historian, but also, like many of his generation, is quite prepared to believe many of the myths that have grown up surrounding Margaret Thatcher’s beliefs and motivations.

This book, and indeed this series of Swift Press books, is not meant to cover every aspect of the life and career of the Prime Minister in question. The aim is simple: to introduce Margaret Thatcher to a new generation – one that lives basking in the glory of her achievements, or was formed in the shadow of her failures, depending on how one views the eleven and a half years of her rule.

She came to power two generations ago, and left office in 1990, before many of this book’s readers will have been born. For historical comparison, imagine I was writing a similar book in 1924, but on Benjamin Disraeli.

The longer a world statesman has been dead, and Margaret Thatcher died more than a decade ago, in 2013, the greater their mythology becomes. As time goes on, fewer people who worked with them survive to correct the myths. Margaret Thatcher is both a victim and a beneficiary of this phenomenon. She was a woman of tremendous paradoxes.

Yes, she was in many ways a conviction politician. She had a basic set of core beliefs and morals, and rarely strayed from them. Once she determined a course of action, it was difficult to persuade her away from it. Yet she was also a pragmatist, someone who was willing to be persuaded by the force of argument. She delighted in her reputation as an ‘Iron Lady’, the epithet given to her by a Soviet newspaper in 1977. Yet she could also be emotional, and even tearful, when confronted by personal or national tragedy.

She could be brutal in some of her dealings with her male ministerial colleagues, yet legion are the stories of her personal kindnesses to them and their families, as well as to her Downing Street staff.

She was known as a monetarist, classical laissez-faire liberal, yet she started out as a social conservative, and wasn’t averse to state intervention when she felt it was warranted.

Her reputation as a cabinet leader was one of being quasi-dictatorial, yet she left her ministers to get on with their jobs, far more than any of her successors ever have. She liked to win an argument, but relished having one. Many was the junior minister who emerged from an argument with her imagining he had ruined his chances of promotion, only to find a few months later that he had been elevated.

She was just as much of an enigma in foreign policy, and there are equally as many misunderstandings about her motives. Many still believe she was a supporter of apartheid in South Africa, yet the facts offer a different version of history. As we shall see in Chapter 9, she played a big role in bringing apartheid to an end, as evidenced by the British ambassador, Robin Renwick, and the fact that Nelson Mandela thanked her for it.

The myth also grew that the Falklands War and the so-called ‘Falklands factor’ was the main reason she won the 1983 general election. The fact is that by April 1982 the economy was starting to turn round, and so were the opinion polls.

Disraeli is said to have created the modern Conservative Party, although I would give the Earl of Derby at least equal billing for that particular accolade. Disraeli’s reputation has been burnished over the 150 years since his death to an extent which defies the historical record. In Britain, Margaret Thatcher has suffered quite the reverse, although internationally she is still viewed as a colossus.

Even thirty-five years after she left office, her legacy is still cited as being at the root of many a modern-day British failure. There is an element of truth in the belief that she still dominates British politics and the economic settlement. She regarded Tony Blair as her proudest achievement, and with good reason. He went down plenty of policy roads which would have caused a degree of queasiness in her later life, but Blair never questioned the basis of the Thatcher economic and industrial settlement. Nor has any government since. Nor do Sir Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves.

In this way, 1979 can be seen as a real political and economic turning point for Britain. Gone was the cosy consensus of so-called ‘Butskellism’, the amalgamation of the politics of Rab Butler and Hugh Gaitskell, the unspoken agreement between successive Conservative and Labour administrations that the job of government was to manage Britain’s economic and international decline. Margaret Thatcher was having none of that. By the time she came to power she had had the best part of five years to prepare for it. She knew that establishment forces in the political, economic and media worlds would be set against her. She knew a large part of her own party would oppose her. She knew she would have to crack a few heads together and court unpopularity, particularly in the early years. There would be huge pressures on her, not least from the majority of her cabinet, to execute economic U-turns when the going got tough. ‘You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning,’ she told her 1980 party conference, with her predecessor Edward Heath looking on and glowering.

It was her ability to use language to turn a threat into an opportunity that stood her in good stead almost to the end. Harold Wilson was the first British Prime Minister to understand the power of television and how it could be utilised to his political advantage, but it was Margaret Thatcher who exploited it innovatively and ruthlessly. She was the undoubted mistress of the photo opportunity, both in election campaigns and on foreign visits. Pictures really did tell a thousand words. The best example of this came just prior to the 1987 general election, when she visited the new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, in Moscow. Dressed in a fur-lined coat and Russian-style fur hat she brought Red Square to a standstill as she went on a spontaneous walkabout. Cheering Russian crowds gave her television pictures to die for. These provided a total contrast to her Labour opponent, Neil Kinnock, who had recently returned from a trip to Washington DC, where he had been humiliated by President Reagan, who had no hesitation in criticising the Labour Party policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

Any Prime Minister whose premiership spans three decades is going to make mistakes and errors of judgement. Margaret Thatcher was no exception, and this book will not shy away from them.

The introduction of the Community Charge, which became known as the ‘Poll Tax’, was chief among them, and directly led to her downfall. Not allowing local councils to reinvest the financial gains from the sale of council houses in new housing stock was another one, which has partly led to the problems the country is experiencing today with lack of supply. The introduction of Section 28 of the Local Government Act in 1988, which sought to ban the promotion of homosexuality in schools, was a catastrophic misjudgement which still blights the Conservative Party’s record on social reform to this day. The fact that Thatcher was one of only a handful of Conservative MPs to have voted for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967 is completely ignored or forgotten.

She placed far too much reliance on the political judgement of Tory whips, who recommended all the junior ministerial appointments. Invariably they promoted so-called Tory ‘wets’ to the government rather than members of her praetorian guard. Even at the end, she still didn’t enjoy majority support in her own cabinet. There was only one person to blame for that. Her. She hated reshuffles and continually appointed the wrong people to the wrong jobs, storing up many problems for later.

There can be little doubt that by the time she left office, Margaret Thatcher had lost that deep connection to public opinion which had served her so well over the previous decade. It was the Westland crisis over the future of a small helicopter company in the West Country in early 1986 which signalled the start of the decline. Indeed, she contemplated resigning at the time, but was saved from humiliation by a poor House of Commons speech by the Labour leader, Neil Kinnock. Eighteen months later, she went on to win a 100-seat majority in a general election, but it was never the same again. The strength of character which voters had so respected transformed into an apparent haughty imperiousness. It was summed up when she commented on the birth of a grandson by declaring to the TV cameras: ‘We have become a grandmother.’ She began to alienate even her closest supporters. When the TV interviewer Brian Walden, who had been a close confidant, accused her of coming across as if she were ‘slightly off her trolley’ following the resignation of Chancellor Nigel Lawson, he was cast into outer darkness, never to be spoken to again.

Party leaders only ever serve at the pleasure of their parties. Maintaining a coalition of support across the big tent is crucial. The way to do that is to keep winning elections, and give your MPs confidence you’re their best bet to hold their seats when the next contest comes. As the 1987 parliament edged towards an election in 1991 or 1992, doubts began to creep in, not least over the Poll Tax, European policy and rising inflation. It was a potent mix. The warnings were there when, in November 1989, obscure backbencher Sir Anthony Meyer launched a leadership challenge. More than 15 per cent of Tory MPs either abstained or voted against her. Alan Clark noted in his diary: ‘This time they haven’t got her, but they will come for her again.’ And they did. A year later Geoffrey Howe resigned and within a month she was gone.

Tony Benn always divided politicians into weathervanes or signposts. Like Clement Attlee, Margaret Thatcher undoubtedly fell into the latter category. Opinion remains divided as to which of these post-war Prime Ministers is the greatest. Poll after poll of university lecturers and professors puts Attlee in first place, but 85 per cent of academics self-identify as being on the left. What is certain is that they both knew their own minds; they knew what they wanted to achieve, if not always how best to achieve it. They both had major foreign and military achievements to their names, but in personality could not have been more different. Attlee ushered in three decades of settled consensus between the parties on Keynesian economic policy, something which shattered under Thatcher. She in turn ushered in a period of thirty years of consensus on the limited role of the state, an industrial relations settlement and the dominance of the private sector in the economy. Only now is this settlement being seriously questioned.

Chapter 1

The Making of a Politician, 1925–59

‘I owe a great deal to the Church for everything in which I believe. I am very glad that I was brought up strictly. I was a very serious child. There was not a lot of fun and sparkle in my life.’

Margaret Thatcher’s childhood and background gave little hint that she might become Britain’s first woman Prime Minister. She was brought up in an unfashionable Lincolnshire market town, Grantham, living above a grocery shop run by her parents, Alfred and Beatrice. It was an austere childhood, with Margaret and sister Muriel, four years her senior, attending a local primary school and then Kesteven and Grantham Girls’ Grammar School.

Politics intruded into the household at an early age, with her father being a local councillor and alderman. He was the major influence on her life and outlook. In later life Margaret barely mentioned her mother, but often teared up when talking about her father. Both her parents came from less well-off backgrounds and had struggled for every penny they had, eventually saving enough to buy the grocery store Alfred managed in one of the poorer parts of Grantham.

Alfred Roberts was an authoritarian and rather intimidating figure, determined to teach his daughter the values of thrift and personal responsibility. He augmented her education and instilled in her the need for hard work to get on in life. The presence of her maternal grandmother in the Roberts’ home life has often been overlooked. She lived with the family until she died, when Margaret was ten. And she was a woman who held basic Victorian values. Cleanliness was next to godliness, and hard work was the essence of a satisfying life. Her role in the young Margaret’s upbringing has never been fully recognised.

Margaret was an intelligent and determined pupil, with clear ambition. Her Methodist religion was important to her, and Sunday school played an integral part in building her outlook on society. Indeed, the girls would go to chapel four times each Sunday. It was only when she started school that Margaret realised that other families didn’t devote their entire Sundays to the Lord. It was a revelation to her that other children in her class played with each other and went on picnics. She questioned her father, who, as ever, sought to teach her an important life lesson: ‘Never do things or want to do things just because others do them. Make up your own mind what you’re going to do and persuade people to go your way,’ he told her, according to an early biographer, Penny Junor.

Her parents clearly loved their daughters, but there were few public displays of affection or obvious signs of wit or hilarity. At school, Margaret was seen by her classmates as a swot. She was the first to raise her hand when a teacher asked a question. She was a loner, a girl who saw socialising as a frivolous activity. Displaying any kind of humour was seen as a sign of weakness.

Margaret worked out at an early age that to get on in life she would need to leave Grantham behind her and make her own way in the world. As she entered the sixth form in 1941 she vowed to get a scholarship to go to university. She overcame obstacle after obstacle, not least the opposition of her head teacher, Dorothy Gillies, who thought seventeen far too young an age for a girl to go to university. But go Margaret did, winning an exhibition to Somerville College, Oxford, to study chemistry. She was on her way.

Oxford must have been a forbidding place for the young Margaret. Never one to make friends easily, she was a fish out of water. Her serious demeanour, together with an inability to have fun and the fact that her lower-middle-class grammar school antecedents often led to a snobbishness being displayed towards her, inevitably meant she concentrated on her studies. It was her membership of the Oxford University Conservative Association (OUCA) which provided a social network, and she threw herself into its activities – both political and social – with a degree of gusto and commitment. Having said that, there is little evidence of her being overtly ‘political’ or identifying with any particular strand of conservative thought. Indeed, she appears, if anything, to have identified with the sort of traditional Tory paternalism that she later came to despair of, or even revile. In 1944 she read F. A. Hayek’s newly published Road to Serfdom, which had a profound effect. It led her to challenge some more conventional conservative thinking. She got to meet many of the Conservative luminaries at the time through her membership of OUCA, including party chairman Lord Woolton. In her final year she became only the third woman to be elected president of OUCA.

Margaret was an unexceptional student, if hard-working. As the years at Oxford went by, her commitment to chemistry started to waver and she began to wish she had studied law. Lawyers, after all, seemed to find it easier to enter politics. But it was too late to change courses. However, in 1946 she met a KC called Norman Winning, who himself had studied physics but then did a second degree in law. She couldn’t afford to do that, but he advised her to get a job in London and do a law conversion course in the evenings.

It was to be several years before she was in a position to do that, but do it she did.

After graduating in 1947 Margaret soon got her first job as a research chemist at BX Plastics in Manningtree, Essex. Lack of money had been a recurrent issue for her at university, and this continued to be the case at BX Plastics, where she earned the princely sum of £350 per annum, £50 less than an equivalent male employee. It is not difficult to see where the notions of frugality, thrift and balanced budgets came from, values which she was to extol throughout her political career.

The late 1940s proved to be pivotal years for Margaret Roberts, both politically and personally. Although she had long since determined she wanted to be an MP, she couldn’t see a pathway to actually achieving her aim. But at the 1948 Conservative Party conference in Llandudno, she was introduced to John Miller, the chairman of the Conservative Association in Dartford, Kent. Three months later she had been selected as their prospective parliamentary candidate. She wasn’t even on the party’s centrally approved list, and yet was able to triumph over four male rivals. And she was just twenty-three years old.

At her adoption meeting on 28 February 1949 she was invited to dinner by a small group of Dartford Conservative Association luminaries, who included Major Denis Thatcher. Margaret had not had any serious boyfriends, either in Grantham or at Oxford. Her studies and politics had taken precedence. Thatcher offered to drive her from Dartford to Liverpool Street station, where she would get the milk train home. Unbeknown to her, Denis had been one of four local businessmen who had been sounded out about the local candidacy, and – like the other three – had refused the overtures. At the time, Margaret was being courted by a Scottish farmer, William Cullen, who seemed keener on her than she was on him. She subsequently introduced him to her sister Muriel, whom he went on to marry.