9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

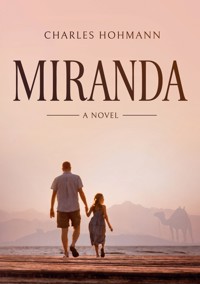

1956 - Alexandria is sinking into chaos. British literature professor Alistair Delmer escapes to Malta with his daughter Miranda. In an unfamiliar land, he wrestles with memory, grief - and the responsibility of comforting a child too young to grasp the meaning of loss. "Miranda" is a quiet novel of farewell and renewal, shaped by a deep love of literature - and of a daughter.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XII

Biography of the Author

Publications

I

It’s midday. A gentle gust of wind sets the wooden shutters rattling, and Miranda steps out into the courtyard. Tabby follows her — the little cat we smuggled aboard the ship, hidden in our cabin, as a stowaway. When we were forced to leave our house in Alexandria in haste, Miranda refused to go without her. Without much thought, I tucked the animal into our travel bag.

I remain standing on the threshold, gazing out at the glittering sea. In the distance, beyond the bay, a small island rises. I gesture towards it.

"Can you see the statue over there?" I ask Miranda.

She looks up at me, curious. "Who is it?" she asks softly.

"Saint Paul," I reply. "They say he was shipwrecked here. Because of bad weather, he couldn’t continue his journey to Rome and stayed on the island for a while. During that time, he is said to have converted the islanders to Christianity."

"And is that really true?" she asks hesitantly.

"That’s how it’s told in the Acts of the Apostles," I say. "But to me, it’s more than just a story. All of us suffer shipwreck at some point in our lives, but the hope for better times endures and gives us courage to begin again."

I have, in fact, suffered shipwreck. I had to leave behind my unfinished doctoral thesis, my teaching notes, my photo albums, all my correspondence, and my entire library in the chaos of our escape. On top of that, I find myself without employment. Only thanks to some savings in England and the support of my in-laws are we just about managing to stay afloat. Miranda, has lost all her dolls and toys too, and misses her school friends terribly. Only the affectionate Tabby brings her comfort and keeps alive the memory of happier days in Alexandria.

Miranda sits down on the stone step in front of the house and gathers Tabby into her arms. Tears well up in her eyes.

"I wish so much that Mummy would come back, " she whispers.

"You know, " she goes on, "sometimes I go to the sea on my own. I lie down in the sand, look up at the sky, and lose myself in its vastness. Sometimes I think I see a figure drifting among the clouds – and I believe it’s Mummy. "

“Mummy once told me,” I reply, “that what dies is only her ‘I’—not her ‘Self’. The ‘Self’ cannot die, because it was never born.”

“I don’t understand,” Miranda interrupts softly.

“Let me explain. The ‘I’ is what we identify with in everyday life — our thoughts, our emotions, our names, the roles we play. It is what feels joy, sorrow and envy. All of that belongs to the ‘I’. And when we die, this ‘I’ fades away — it dissolves.”

I pause and look at her.

“But the ’Self’,” I continue, “is something entirely different. It is what is eternal within us. The unchanging, the immortal. It is connected to all living things — to the whole universe. Some call it the divine within us.”

I gently brush her fringe aside.

“That’s why Mummy also said: ‘You’ll find her again in the whisper of the wind, in the dancing white crests of the waves, in the drifting clouds. She is everywhere now, watching over you.’”

I miss Hannah just as much. But unlike me, Miranda doesn’t yet fully understand what death means. For her, it’s comforting to think that her mother is still somewhere, even if she can’t see her. Looking up at the sky helps her believe that her mother is still close.

I often look up too. In the seemingly empty sky, I see tiny points of light flickering. They shift and change, appearing at different depths, sometimes forming triangles or prism shapes. Seeing this again and again, I’ve come to feel there must be other worlds beyond the one we see — vast, limitless spaces that hint at something far greater than we can understand.

The midday sun warms the walls of the house. It is built from that pale, honey-coloured limestone that glows in a warm, golden light. In the narrow courtyard between the house and the low stone wall, a fig tree stretches its branches towards the light, its leaves casting dancing shadows on the cracked ground.

Inside, it is cool and dim, with soft beams of sunlight filtering through the green-painted shutters. The fragrant air is laced with hints of lemon peel, olive oil, and a faint trace of paraffin, coming from the small kitchen where a pot of rabbit and bay leaf broth simmers on the gas stove — thanks to our landlady, Maria. Barefoot and wrapped in a floral cotton dress, she stirs it with a wooden spoon brushing a strand of hair from her forehead.

"Almost ready!" she calls from the kitchen.

A few weeks ago, after disembarking in Valletta from the corvette — the ship that had carried us to safety from the chaos of war-torn Alexandria — I decided to remain on Malta. We needed peace, time to breathe, a place where we could begin to plan our future anew. I found out that the local police station kept lists of available rental properties — emostly houses owned by Maltese families who had temporarily moved in with relatives to earn some income from letting them out.

I was immediately drawn to St Paul’s Bay. It was there that I had once held Hannah in my arms for the first time. I still remember our joyful conversations aboard the Mauretania; that ship connected both of us to this place in a way I could never fully explain. When a house in the area was recommended to us, we went to have a look. At the time, the bay was a quiet fishing village, with scattered houses, unpaved tracks, and a community still living in harmony with the rhythm of the sea.

The house for rent was on the western side of the bay: a single-storey dwelling, with thick stone walls that kept out the heat, and deep-set windows behind wooden shutters to provide protection from the sun.

We often climb up to the flat roof, where the washing is always drying and pots of kitchen herbs are neatly lined up. Rainwater collects in a cistern. We liked the house immediately and agreed to rent it from the owner, Maria, who had greeted us with heartfelt warmth. Maria has that kind of openness one only finds in very simple surroundings. She regularly brings us vegetables and fruit and sometimes treats us to delicious local dishes.

On the wall in the living room hangs a picture of the Holy Family, beside it a slightly crooked crucifix above a plain chest of drawers. On top of it stand two worn porcelain vases – one filled with fresh rosemary, the other with fading bougainvillea branches.

Tabby lies stretched out on the settee in the corner of the room, her eyes half-closed, watching every movement in the kitchen.

Miranda and I are already seated at the laid table when Maria enters, carrying a steaming enamel bowl and letting us taste the rich stew. It’s absolutely delicious, and before long the bowl is scraped clean, with Tabby getting a piece of rabbit. For dessert, Maria brings a dish of oranges and bananas.

After the meal, I suggest a walk to the bay — that small, half-forgotten cove Hannah and I once reached by swimming, unaware at the time that the beach was still mined. We had to be rescued by a patrol of soldiers.

Swimming, of course, is out of the question at this time of year. It’s November, and the water is cold. But we can take the long route there, down a footpath through a small, walled valley, its blocks of honey-hued stone once laboriously piled up by the local farmers, stone by stone. Maybe the Greeks named the island 'Melita' after the hue of its stones — the word means 'honey' in their language.

Miranda agrees at once. I can see how much she wants to talk about her mother, and her questions strike me like tiny arrows — insistent, full of longing. With each anecdote I share, Hanna seems to come alive for her just a little more.

The variety of plant life in the limestone valley is surprising: cacti, palm trees, towering reeds, birches, and azaleas line the uneven path of packed earth.

After thirty minutes we reach the bay — and only now do I learn its name from a weathered signpost: Mistra Bay.

The sea below us shimmers in a range of green shades, depending on the nature of the sea bed. Where thick mats of algae lie, it appears dark green; over rocky ground, it shifts between green and blue. Where the bottom is sandy, it glows a clear turquoise. Further out, as the sea grows deeper, it turns a dark, almost velvety blue. Light dances on the rippling surface resembling the shimmer of moiré fabric.

“Here,” I say, pointing to the sandy stretch, “right here is where I was lying with your mother when suddenly we heard a shout from the hillside. A sentry called down to us, telling us not to move — the bay was still mined. Moments later, soldiers came by boat, cleared a safe path, and got us out unharmed. It was here, in this very spot, that I held your mother in my arms for the first time.”

We continue along the path to the end of the headland. Across the narrow strait lies the island with the statue of Saint Paul. On either side of the headland, waves crash thunderously against high cliffs. It’s easy to imagine the ship St Paul was travelling on being wrecked here.

I point to an island on the horizon. “That’s Gozo,” I say. “According to Homer, a ship once met its end there — the vessel of the cunning Odysseus, one of the greatest seafarers of all time. He survived and spent seven years in seclusion on that very island — with the nymph Calypso.”

On the way back, Miranda stumbles over a slight ridge in the ground — likely part of the deep cart ruts that crisscross the island like a mysterious network.

“What are those grooves for?” she asks, a hint of irritation in her voice.

“No one knows for certain,” I reply. “It’s believed that a prehistoric people carved them — perhaps for sleds or large runners used to transport heavy stone blocks. Some Maltese even claim the tracks continue beneath the sea. But even the history books offer no clear explanation.”

We continue strolling past the old Royal Air Force rest house — the place where Hannah and I once spent an afternoon, just before setting out on our nearly disastrous swimming expedition.

“Tell me more about Mummy,” Miranda says softly.

I pause for a moment and then reply, “I’m going to write down the whole story of our love — right here in Malta. I’m sure your grandparents and Hannah’s friends would want to read it too. Tomorrow, I’ll buy some notebooks; and then I’ll begin.”

She looks at me gratefully and nestles up to Tabby. I fall into thought. They say that what is not remembered and recounted never truly existed. Only through telling and writing can the past be preserved from oblivion — and thus be granted a new reality. Miranda has a right to that; and I find that I need it too.

The next morning, after breakfast, we walk to the nearby fishing village. In a small general store, I buy half a dozen exercise books, a set of pens, and some envelopes. Miranda asks for drawing paper and coloured pencils which we no longer had. At the post office, I leave our address. Right next to it stands a public telephone box — our only link to the outside world.

In the bay below, fishing boats and barges bob on the choppy water. The November wind is picking up; gusty weather is nothing unusual here.

We sit down at a rickety table in a small café on the quay and place our order — a lemonade for Miranda, a coffee for me.

“It’s so lovely here. How long can we stay?” Miranda asks.

She’s ten now. With her delicate features and the blonde curls that frame her face, she looks so much like her mother — the woman I loved more than anyone or anything in the world.

“I can’t say for certain at the moment,” I reply thoughtfully. “I’ll apply for a post at a college or a university. Only once I know where we’re headed can I start thinking about settling properly in England. If necessary, we could stay with your grandparents for a while; but that wouldn’t be a long-term solution. Are you feeling bored already?”

“Not really. I just miss my violin… and my favourite books. Mummy taught me how to paint, and now at least we’ve got coloured pencils. But it would be nice to have a few books and a doll. I haven’t seen a single girl my age here — no one to play with, hardly any children at all.”

“I’ve got an idea,” I reply. “Tomorrow we’ll go to Valletta and have a look around. Perhaps we’ll find something there to cheer you up. And this evening I’ll write to your grandparents; they must be missing you terribly. I’ve no doubt they’d love to come to Malta. What do you think?”

A shy smile flits across Miranda’s face, which in recent weeks has looked downcast and sad.

“I won’t sleep a wink tonight from all the excitement,” she whispers.

On a cool, clear November morning, Miranda and I set off for Valletta. The bus lurches along the winding roads, past low stone walls and tiny chapels, before dropping us near the city centre. From there, we continue on foot, heading straight into the heart of the city.

The alleyways are still quiet. Only now and then do we hear the clatter of shutters, a vendor’s call, and the distant howl of the wind coming in from the sea. Last night’s rain has left the paving stones of Kingsway glistening darkly. With each step, our shoes squelch against the damp stone. Miranda walks beside me, holding my hand, her eyes wide and alert, taking everything in. Her blonde hair blows in the breeze, and for a moment, a part of Hannah feels very near.

We stop outside a stationer’s shop where a set of watercolours is displayed in the window.

“We’ll buy it,” I say decisively, “and later you can paint me a picture of Mistra Bay, yes?”

She responds with a persuasive smile. “And you’ll write about Mummy?”

I nod. “As promised.”

We walk on. In front of St John’s Co-Cathedral, we pause for a moment. The heavy baroque façade towers over the square. A British soldier leans against a stone pillar, smoking, looking tired. Miranda watches him with innocent curiosity. I, however, feel a flicker of unease: the uniform and the quiet gravity in the man’s eyes stir memories of other times, other places: Dabaa. Alamein. Alexandria.

“Would you like to sit down?” I ask Miranda.

She nods. We stroll over to a bastion and sit on a stone bench. Before us stretches the open sea, deep blue and restless. In the distance, the ferry to Sliema begins its slow, almost stately crossing. Gulls screech over the bay.

“Mummy said the sea never stops telling stories,” Miranda says suddenly.

I turn to her and look at her. Her voice is calm, almost dreamy. “She really said that?”

“Often,” she replies, without meeting my gaze. “When we painted together. She said you just have to listen closely.”

I put an arm around her shoulders. We sit like that for a long while, without speaking, a soft wind brushing our faces and the warm sun breaking through a band of clouds. Everything in Valletta is still — as if the city itself were holding its breath.

Then the wind starts to pick up, so we rise and stroll on down Merchant Street, past a shop selling lace curtains, a watchmaker’s and an antiquarian bookshop with faded bindings in the window. A little further along, we come across a shopfront that feels like a quiet promise: a doll’s shop — old-fashioned and almost invisible between two newly restored façades.

Miranda comes to an abrupt halt. Behind the glass sits a porcelain doll with dark, round eyes, a frilled blouse, and a tartan skirt. Brown curls tumble over her shoulders.

“That one…” Miranda whispers. “Do you see how she wants me?”

I open the door and a small bell jingles; the scent of wood polish and old paper hangs in the air. Behind the counter sits an elderly lady with grey hair in a bun and a pincushion strapped to her wrist. She smiles without getting up and nods to us kindly.

We step closer. Miranda hardly dares to breathe. I ask about the doll in the window, and the lady retrieves it for us. As Miranda gently takes the doll, she rests her forehead against the cool porcelain and briefly closes her eyes.

I watch silently as she stands there with the doll in her arms. And suddenly, images rush through my mind: Hannah on a winter morning, barefoot at the bedroom window in Alexandria, her hair tousled. I see her bend down to pick up one of Miranda’s drawings, looking at it with quiet reverence. “She’s just like you,” I had said to her then. She smiled—tired, but full of warmth: “Then I know you’ll always be kind to her.”

I feel my throat tighten. The doll, the shop, the light — all of it isn't truly important. And yet, there’s something comforting in it. Miranda will carry Hannah within her in her own way, but she also needs me — and what I will write — to do so.

“Can I give her a name?” she asks softly, as we step back onto the street.

“Of course.”

She thinks for a moment. “Maybe Hanna?”

I nod. “A lovely name.”

Then we make our way to the Sapienza bookshop, which I remember from my first visit ten years ago. If I’m to resume work on my doctoral thesis, I’ll need to find the same books I used back then. The first step will be to reengage with what I once wrote — and have since lost. So I search for works by T. S. Eliot, Henri Bergson, Augustine, and the Vedic texts I once consulted. The latter I can’t find; I’ll have to order them from England.

Miranda chooses a few books of her own, and I hand her a copy of Shakespeare’s The Tempest — so she’ll know where her name comes from.

We continue our walk, slowly, heavy bags in hand, through the narrow streets of Valletta, glowing in the golden November light. And as my eyes fall upon the doll in the bag, I realise that this evening I will begin to say what still needs to be said.

For Miranda.

For me.

For both of us.

II

5 April 1945. It is noon at Gladstone Quay. The sun shines bright and clear from a cloudless sky.. Seagulls circle overhead, their hoarse cries mingling with the metallic clang of heavy iron chains hoisting containers from the docks. When loads crash onto the deck, the sound echoes across the water.

Officers in immaculate white naval uniforms shout orders. Soldiers in khaki shorts and woollen knee-high socks stand at attention, rifles firmly in their right hands, their standard-issue packs tightly strapped, helmets worn upright. Sailors shouldering hefty sea bags bid farewell to their families. Patriots wave Union Jack flags.

Beneath the towering metal arms of the loading cranes, the activity is overwhelming — a deafening chaos of shouts, thudding cargo, and roaring machinery that even drowns out the marching music of the brass band.

I stand in a queue, waiting to be allowed on board. The massive hull of our ship, the HMT Mauretania, looms over the dockside. I had seen pictures of the old HMS Mauretania with its four funnels. But the HMT Mauretania II, before which I now stand — launched just six years ago — has only two. Yet nothing could have prepared me for the sheer size of this behemoth. Just months ago, it was a luxurious ocean liner of the Cunard White Star Line. Now, the ship is painted in wartime lead-grey camouflage.

Suddenly, I feel a hand on my shoulder. I turn around … "Alistair, how wonderful to see you again! What are you doing here?"

The voice belongs to an old friend, Captain Vic Stepcox. We both attended Downforth Abbey School. While I studied at Oxford, he earned his officer’s commission at Sandhurst. Later, our paths crossed again in Germany, where he commanded a unit of the South Lancashire Regiment.

His face is angular, tanned by the sun. A loose brown lock of hair escapes from beneath his officer’s cap.

As my turn to board is approaching, I reply hastily, "I’ve been assigned to Alexandria as an interpreter. I’m to mediate between German prisoners of war and their British camp commanders in four detention camps, relaying their concerns and translating orders. And you? Where are you off to?"

His joy at our reunion fades. With a serious expression, he says, "My unit is being deployed to Burma. The Japanese are in retreat there. Our troops have taken Mandalay, and now our mission is to liberate Rangoon. In Europe, Germany’s defeat is becoming apparent; so troops are being redeployed accordingly."

Then his face brightens again. "If you’d like, let’s meet on the promenade deck once we’ve settled in."

A sly grin accompanies his next remark: "I met an incredible woman here in Liverpool. She’s with the WAAF and is also travelling on the Mauretania with her colleagues."

"You incorrigible womanizer," I remark with a smirk. "You really don’t waste any time..."

At last, it’s my turn. A stocky officer with a weathered face, scruffy chin stubble, and a worn-out tunic eyes me appraisingly.

"Name?"

He has light, friendly eyes that regard me with an easygoing curiosity.

"First Lieutenant Alistair Dempster, interpreter," I introduce myself.

"Welcome aboard! All officers and NCOs are accommodated in either two- or four-person cabins. You’ve been assigned a two-person cabin on the upper deck: number 125. Your cabin mate is a captain named Alan Penrose. Take the lift here; your cabin is one deck up, about midway down the corridor. I wish you a pleasant journey."

I find the cabin quickly, but my roommate has not yet arrived. I let my gaze wander through the small space: a bunk bed with a washbasin beside it, a small sofa, and a desk.

I unpack my belongings and settle in. Laundry and uniforms go into the narrow wardrobe, toiletries on the sink, books and writing materials on the desk. Then I step up to the porthole. Through the thick glass I look out onto the harbour bay where bustling ship traffic unfolds: tugs, freighters, and barges crisscross between the docks.

Finally, I decide to head up to the promenade deck to meet Vic.

He’s already there, leaning against a davit, gazing over the towering ship’s side at the busy activity on the quay. We greet each other once more, this time with a firm handshake.

The scene below us is a living mosaic of colours and shapes — a tangle of uniforms from various military units, interspersed with waving relatives bidding their farewells. More than 4,200 passengers are embarking: among them, 4,000 soldiers, sailors, and Royal Air Force personnel en route to Egypt, India, and Burma, where the war against the Japanese still rages. Additionally, around 200 women from the RAF auxiliary forces, the so-called WAAFs, as well as a few civilians, are on board.

"Let’s take a little tour," Vic suggests.

He points to the 6-inch guns mounted on the foredeck after the outbreak of the war, along with smaller artillery pieces.

"Of course, this isn’t a real warship. This armament is more symbolic than anything. But we’ll be escorted all the way to Suez by a C-class cruiser, the HMS Cavendish. By the way, the ship is carrying an additional 400 tons of raw iron and 700 tons of ballast to improve its maneuverability and stability."

I let my gaze wander over the ship. It has two masts — one smaller one aft and a taller one on the foredeck. Vic points to a masthead platform halfway up.

"A relic from early seafaring," he explains. "Unlike the crow’s nests on old sailing ships, where the lookout was exposed to wind and weather, this structure is more like a small cabin. Whoever keeps watch up there is well protected."

"But why even have a lookout?" I ask. "We have radar and ASDIC, not to mention an escort cruiser."

Vic nods but replies, "The greatest threat comes from German U-boats. When they travel just beneath the surface, they are difficult to detect despite all our technology. However, their periscopes leave a faint white trail in the water — and a skilled lookout can spot it."

Several hours pass before the ship is finally ready for departure. Then, the deep roar of the ship’s siren sounds.

At the stern, on the navigation deck, signal flags are hoisted, signalling to HMS Cavendish, whose funnel is already releasing a dark plume of smoke. Moments later, the Mauretania begins to move.

From the quay, the last farewell calls float over. Relatives wish the soldiers luck, waving handkerchiefs. Dockworkers loosen the thick ropes from the bollards, then two tugboats slowly pull the steamer away from the pier. The pilot boat takes the lead. Slowly, the ship glides toward the Irish Sea.

On the horizon, Liverpool’s skyline begins to shrink — the high-rises, the rectangular tower of the cathedral. The fluttering handkerchiefs and waving hats of those left behind become tiny dots. The cheers of the crowd fade into the wind.

"Come on, let’s take a little tour of the ship’s interior," Vic suggests enthusiastically.

First, we step into the grand hall. What was once a magnificently decorated space — with a domed ceiling of glass and wrought iron, encircling galleries, Ionic columns, and ornate ceiling paintings inspired by Pergolesi’s motifs, framed by delicate papier-mâché stucco — has lost its former splendour.

Along the walls, metal frames with bunks bolted to them are occupied by soldiers sitting or lying down. The elegant walnut panelling is now interrupted by heavy metal reinforcements. In the centre of the room are simple wooden tables around which men play cards, read, and joke.

Above their heads, the hanging fixtures for the heavy crystal chandeliers — removed for safety reasons — are still visible. Everything that could have become a dangerous projectile in an attack — statues, display cases, fragile decorative pieces — has disappeared.

When the soldiers notice us — two officers — they jump to their feet and salute. We return the greeting saying we won’t disturb them. Some men from Vic’s unit greet him with a handshake and friendly banter.

The adjacent halls present the same scene.

We take the elevator down one deck, but a duty sailor denies us entry. This area houses the 200 female RAF personnel, all accommodated in four-person cabins.

We continue our tour and reach D-Deck, passing through the grand dining hall with its intricately patterned tile floor. The room is over 30 metres long, and feels oppressively empty.

Further along, we pass by the indoor swimming pool. Instead of shimmering water, crates of supplies are now stacked high. The once beautifully designed space still speaks of another era: the walls adorned with vivid depictions of ancient scenes. To the left, a queen sits in a magnificent salon, her figure reminiscent of Cleopatra enthroned on a golden chair, surrounded by overturned satin trunks, ivory vials, finely cut glass flacons, and sparkling jewels. To the right is a scene from Ovid’s Metamorphoses: King Tereus, at the very moment he lays eyes on Philomela, his wife’s sister, and falls hopelessly in love with her.

Vic wants to take a look at one of the former private promenade decks. These verandas, along with the adjoining smoking lounges with their exposed wooden beams, are reminiscent of the English Tudor style. Comfortable wicker chairs invite passengers to linger, while large arched windows offer a view of the slowly shrinking silhouette of the city.

Finally, we decide to retreat to our cabins until dinner.

I knock on my cabin door — Captain Penrose might already be there. A brief "Come in!" prompts me to open the door, and I find myself facing a tall man who extends a bony hand. Serious grey eyes study me intently, but his broad, welcoming smile softens the severity of his gaze. His face is tired, weathered by wind and sun.

He greets me in a firm voice and introduces himself: "Alan Penrose, Captain, Armoured Corps, 2nd Fife and Forfar Yeomanry. I’m on my way to Gibraltar to reunite with my family. I’m leaving the army. I was in Normandy — took part in Operations Goodwood, Bluecoat, and Epsom — and fought in the Ardennes Offensive. I’ve seen enough. I see you wear the insignia of a First Lieutenant."

"Yes, but my rank is more symbolic. I’m a translator — I haven’t attended officer school, nor am I a particularly good marksman. In battle, I’d probably be more of a danger to others. But since I interpret for high-ranking German officers and generals during interrogations and military tribunals, they believe the rank helps with credibility. Of course, I have no command authority."

My gaze falls on a framed photograph on his bedside table — a woman with two small girls.

"Is that your family in Gibraltar? They must be in for a wonderful surprise when you reunite!"

His face brightens. "After so many years, I can hardly wait to see them for real. My wife and daughters only recently returned to Gibraltar from Madeira. Before the war, all civilians were evacuated from the enclave — some to England, others to Madeira — because Gibraltar was a tempting target for the Axis powers. Hitler’s General Staff had developed Operation Felix back then, planning to seize this strategically vital stronghold."

He pauses briefly, as if lost in memories, then lifts his head.

"But I didn’t realize there were official interpreters in the army. In our prisoner interrogations, we always relied on soldiers who happened to speak German."

His eyes rest on me questioningly. "Do you have a family? Children?"

"No," I answer hesitantly. "I’m divorced and have no children. But I’m glad to be sharing the room with you. I’m sure we’ll have plenty to talk about."

Captain Penrose casts a curious glance at the two books on my nightstand and gestures toward them.

"What are you reading? May I?"

He picks up the thicker volume and reads the title.

"Being and Nothingness by a certain Sartre. That’s certainly no novel. Difficult reading! And this one … Matter and Memory by Henri Bergson. Are you a philosopher?"

I smile. "No, just an amateur. But at the moment, I’m fascinated by the ideas of the French. I admire Bergson not only for his thoughts but also for his integrity. When the Vichy regime under Marshal Pétain brought in legislation to discriminate against Jews, he refused to deny his origins. In 1940, he demonstratively renounced all his honours, titles, and memberships and had himself registered as Jewish out of solidarity."

Leaning back, I add, "But you know, in a way, we’re all philosophers. Everyone contemplates their role in the world. Some do it systematically, others more casually. But for now, I’m simply looking forward to the days we’ll be spending together."

A knock at the door interrupts our conversation.

"Come in!"

A sailor opens the door and announces briefly, "At 6 p.m., all officers and non-commissioned officers are to assemble in the grand hall on A-Deck. Captain Seymour will be giving a speech."

I glance at my watch. "Then we’d better hurry."

By the time we reach the grand ballroom, hundreds of officers and NCOs have already gathered. Most remain standing—there aren’t nearly enough seats. A low murmur fills the room.

Then, the First Officer steps onto the stage and announces the captain. Instantly, silence falls.

Captain Seymour appears, greeting the audience in a warm, almost collegial tone. But I immediately notice two things: his yellowed skin, unmistakably marked by years spent under the tropical sun, and the slight limp that accompanies his steps.

The captain clears his throat briefly, then addresses the assembly. His voice is calm, resonant, and carries effortlessly through the room:

"As you can see, I have an injured leg — the result of shell fragments from an enemy ship’s cannon. I was fortunate to survive, while others gave their lives for God, King and country. My mission now is to bring you all safely and unharmed to your destinations."

He pauses briefly, letting his gaze sweep over the crowd.

"It is important to me to prepare you right at the start of our journey for what lies ahead. Our greatest danger comes from German U-boats that may be lying in wait. The German submarine fleet has been severely diminished, but a few of these beasts are still patrolling the coastal waters; their torpedoes remain a serious threat. According to intelligence reports, U-485, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Lutz, is particularly active. It left La Pallice on 29 April and is probably lurking off the Spanish coast right now."

He clasps his hands behind his back. "To deceive the U-boats, we will first sail west for 48 hours — making them believe we’re headed for New York. Only then will we change course and head for Gibraltar."

After a brief pause, he continues, "Our detection technology can locate submarines in the water, but things become tricky when they creep up at periscope depth. That’s why we will have lookouts scanning the ocean surface around the clock for suspicious water disturbances or torpedo trails. The lookout post will always be manned — its high vantage point allows for a wide view beyond the horizon."

He gives a sharp nod. "HMS Cavendish will stay close to us, ready to attack any sighted U-boats immediately. Absolute radio silence is ordered while we are in the Atlantic. At night, we will travel without lighting; only the dim red emergency lights will illuminate common areas and corridors. All military personnel have been issued flashlights, in case they need to find their glasses or dentures in the dark."

A brief smirk crosses his face. "Let’s hope none of you brought a hip flask."

Laughter ripples through the hall.

The captain raises his hand to regain attention. His voice takes on a serious tone once more: "I also ask you not to throw anything overboard. Even small objects can provide the enemy with clues to our position. In the coming days, we will conduct regular drills to ensure everyone knows the necessary procedures in the event of a torpedo attack. These will include theoretical sessions on survival strategies at sea, as well as evacuation exercises for fire outbreaks and water breaches."

He pauses briefly, then continues: "Physical exercise will not be neglected either. Life jackets are mandatory: anyone stepping onto the deck must wear one and always have it within reach. For security reasons, I will not disclose detailed information about our route or the specific stops along our journey. However, what I can tell you is that if we maintain our average speed of 20 knots, we should reach Gibraltar in six days."

He nods to the First Officer. "First Officer Herbert Turberville will provide you with further instructions after I’ve spoken."

The captain pauses briefly, as if carefully choosing his next words. "Now, gentlemen, I would like to invoke the protection of the Almighty for our journey. Let us join together in singing Psalm 31. Our chaplain, Reverend Balthasar Lawrence, will accompany us on the harmonium."

(...) But I trust in you, LORD! I declare it and hold fast to it: You are my God! My times are in your hands. Deliver me now from the power of my enemies and from those who pursue me! Turn your face toward me, your servant, with favour! Be gracious to me and save me!

"Let us also remember the many comrades who have sacrificed their lives in this war for home, King, and faith — on land, at sea, and in the air."

A minute of silence follows. The hall is still.

After a while, the captain continues: "I won’t keep you much longer, but allow me to share an adapted quotation from Churchill: We have endured many long months of struggle and suffering. We have waged war — on water, on land, and in the air — with all our strength and with the power God has given us. We have stood against a monstrous tyranny, one that finds few equals in the dark catalogue of human crimes. But now, final victory is near — and it is certain. May God protect you all.

"It only remains to wish you a good and safe journey. The high mercury in the thermometer and the barometer promise fine weather and calm seas."

Applause erupts.

Then, the First Officer steps forward and takes the floor. He issues the day's orders while the entire crew and personnel are informed via loudspeakers.

To conclude, he announces that meal service will now begin. Meals will be served in three shifts, and everyone can check the posted list to find their time.

Since it is still light out and I am assigned to the last meal shift, I decide to join a few others on the open promenade deck to get some fresh air before dinner.

After dinner, I meet up with Vic again. A light breeze is blowing over the deck, so we tuck our caps under our epaulettes.

The sea stretches into an endless, deep black expanse, with the sky arching above in dark blue, sprinkled with points of light. Only at the western horizon does a narrow, pale blue crescent still shimmer. Despite the darkness, faces are still clearly visible.

All over the deck, soldiers — both men and women — stand in small groups, leaning against the railings, smoking and chatting. People speculate about the upcoming destinations of the journey, but no one knows anything for sure. Just a few months ago, a sky this clear would have been an inviting target for enemy bombers.

"Want one?" Vic asks, flipping open a silver cigarette case, revealing two neatly stacked rows of cigarettes.

"I smoke occasionally. I'll gladly take one now."

I select a Navy Cut; Vic retrieves a Zippo from his side pocket, flips it open with a practised motion, and lights my cigarette. As he lights his own, he murmurs, "A GI friend gave it to me. Supposed to last a lifetime and can be used with one hand. Brilliant invention!"

I take a few drags, squinting against the sharp, acrid smoke. It burns in my lungs, but feels oddly pleasant at the same time.

"Amazing how they manage to feed 4,000 people multiple times a day," I say aloud. "Even with three meal shifts, that still means over 1,000 people eating at once in the different halls!"

A few soldiers pass by, greeting us. One of them stops, and Vic introduces him:

"This is Private Stearns Murray — the poet of our regiment."

Murray, a heavy-set man with a bald head that gleams dully under the deck lights, blinks shyly behind thick glasses and extends his hand.

"Too much honour!" he says in that distinct Irish brogue that makes words sound round and melodic. "I jot down a few verses now and then, but my true passion is reading."

"But you've written books," Vic interjects. "I saw one lying on your bed."

Murray reaches into his leather shoulder bag and pulls out a pipe along with a tamper. As he pokes around inside the bowl, he deftly pinches some tobacco from a drawstring pouch and packs it in with care.

"Yes," he finally says, "but the urge to write left me on the battlefield. I keep a journal at most. And now our unit is turning a new page in Asia. Fighting the Germans was one thing; but after all these years in Europe, having to go up against the Japanese as well won’t be a walk in the park."

Vic runs his hand through his wind-tousled hair, his expression serious. "The Americans have taken Manila, liberated Iwo Jima, and now Okinawa. Tokyo has been bombed, and we will capture Rangoon. The Japanese are in retreat. Our role will mainly involve securing liberated areas and assisting the new administrations. But for now, we’re on this wonderful voyage, a chance to rest. In a few days we’ll reach Gibraltar where we can enjoy the blooming spring from the Rock."

Murray unscrews the mouthpiece of his pipe and peers into the stem, clearly stalling to avoid direct eye contact. As he fumbles, he mutters, "April is the cruellest month."

Vic looks surprised. "What do you mean? Spring is when nature awakens, the trees grow new leaves, plants sprout, seeds germinate — it’s warm again. Poetry celebrates spring as the first phase of human life, symbolizing childhood and youth. What’s cruel about it?"

Murray blows into his pipe and tamps it down again. As he tilts his head to light it with a match, he glances over the rim of his thick glasses and replies, "Yes, the first spring flowers — pale and velvety, promising future joy and life — are praised a thousandfold by poets. But there is also the opposite tradition, an opposing belief: the conviction that the rebirth of nature and human hopes in spring is a curse.

"According to the Gnostics, humanity is trapped in a cosmos created by a malevolent god — a demiurge — from which they must escape. True freedom lies in another sphere, beyond the world in which we live. This belief in a flawed world, ultimately filled only with sorrow and suffering, has underpinned the spiritual currents of Christianity for aeons. The line ‘April is the cruellest month’ is from Eliot’s The Waste Land, and its interpretation offers a window into this rich, darker undercurrent of thought. Cathars and Bogomils gave their lives for this faith, which echoes in the works of many poets — not just Eliot but also William Blake, whose verses are steeped in Gnostic references."

He leans back, puffing on his pipe, the ember glowing faintly in the dark. "Speaking of which, knowing we’d be at sea, I packed my copy of Moby-Dick. Let me read you something — it’s right here in my bag."

Murray rummages through his leather bag, where he keeps his pipe and writing tools, and pulls out a thick, well-worn book. He opens it to a page marked by a dog-ear and begins to read aloud:

“We are all surrounded by whale-lines. We are all born with halters around our necks; but it is only when caught in the swift, sudden turn of death that mortals realize the silent, subtle, ever-present perils of life.’”

Vic furrows his brow. Two deep lines crease between his eyebrows, clamping down on his blunt nose.

"That's new to me. But I can understand how one might arrive at such a bleak worldview — especially when thinking about the past years and months of horror, suffering, and death. And wondering, for what?"

I understand Murray’s perspective — both in regard to Eliot’s verse and Melville’s lines. Was Ahab not the ultimate Gnostic, and was the great white whale not the incarnate demiurge?

The Gnostic thinking that Murray spoke of has always fascinated me. And I have long been convinced that it did not only flourish in antiquity and the Middle Ages but lives on in our time as well. When I think of my readings of modern existentialists, I recognize the same view of the world — only without the religious and mythological framework.