1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

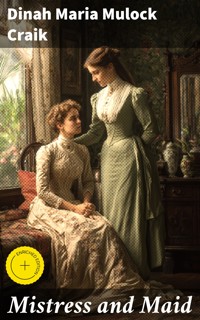

In "Mistress and Maid," Dinah Maria Mulock Craik dives into the intricacies of the Victorian social hierarchy, exploring the nuanced relationships between women of differing social standings. The narrative, which intertwines elements of social realism and moral didacticism, illuminates themes of compassion, loyalty, and the quest for agency amid societal constraints. Craik's adept use of dialogue and vivid characterizations creates a rich, immersive world that captures the struggles and triumphs of her characters, making the text a significant study of gender dynamics during the 19th century. Craik, a prominent Victorian novelist and poet, often drew from her own experiences as a woman navigating the literary landscape of her time. Her commitment to addressing women's issues and the societal limitations imposed upon them is evident throughout her oeuvre. Growing up in a middle-class environment and facing the challenges of self-assertion in a male-dominated society may have influenced her narrative choices, underscoring her profound empathy towards women from all walks of life. "Mistress and Maid" is not merely a tale; it is a poignant commentary on the era's social fabric. I highly recommend this work to readers interested in feminist literature, Victorian social studies, or anyone seeking profound insights into the human condition. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Mistress and Maid

Table of Contents

Introduction

This novel traces how intimacy and inequality intersect within the walls of a household, testing loyalty, duty, and the fragile bargains of everyday life. Mistress and Maid invites readers into the domestic sphere where private emotions and public expectations constantly collide. The story proceeds not through grand spectacles but through the quiet pressures of work, care, and conscience, showing how ordinary choices accumulate into moral consequence. Its world is one of parlors, kitchens, and thresholds, where roles are learned, contested, and sometimes reimagined. The result is a study of character in close quarters, attentive to the everyday texture of Victorian social life.

Written by Dinah Maria Mulock Craik, Mistress and Maid belongs to the tradition of Victorian domestic realism and is set in England during the mid-nineteenth century. Published in the Victorian era, it reflects the period’s fascination with the home as both refuge and arena for social testing. Craik’s fiction is known for clear moral vision and sympathetic attention to women’s experience, traits that shape the book’s focus on the relations between employer and servant. Readers encounter a social landscape structured by class and custom, yet permeable enough to reveal personal agency, ethical choice, and the complex dynamics of dependence and care.

The premise centers on a household in which a woman of modest means and a young maid navigate the responsibilities and vulnerabilities of their bound roles. Through daily routines, crises small and large, and the scrutiny of neighbors, their relationship becomes a lens on status, trust, and survival. Craik’s narrative voice is measured and observant, favoring psychological insight over melodrama. The mood is earnest and humane, with moments of tenderness set against the firm edges of duty. Readers should expect a steady, closely observed story that treats simple acts—hiring, serving, paying, forgiving—as decisive moral events.

At the heart of the book are themes that preoccupied Victorian readers and still resonate today: the dignity of labor, the limits and promises of respectability, and the ethics of power exercised at home. It considers how character is tested by money, illness, and reputation, and how obligations can bind people together even as they enforce inequality. The novel also probes female solidarity and conflict, exploring how women negotiate authority, self-respect, and livelihood within a system that restricts their choices. In emphasizing mutual responsibility, it asks what justice looks like when one person’s shelter is another’s workplace.

Craik builds tension through the rhythms of domestic life, turning household tasks into narrative scaffolding and allowing minor incidents to reveal larger social truths. Dialogue is used to register shifts in confidence and class position, while quiet descriptive passages ground the reader in rooms where every object signifies rank or restraint. The prose favors clarity and moral precision, declining sensational twists for accumulated insight. Scenes of accounting, caregiving, and confrontation form a pattern of trial and response, encouraging readers to weigh motive as carefully as outcome. The effect is a patient realism that honors the gravity of the ordinary.

For contemporary readers, Mistress and Maid offers a historically rooted reflection on questions that persist: Who bears the costs of comfort, and how should care be valued? The book illuminates emotional labor, boundary setting, and the ethical texture of employment relationships—issues recognizable in modern debates about domestic work and the care economy. It invites empathy across class lines without idealizing dependence, showing how kindness can coexist with coercion and how integrity may demand sacrifice. By dwelling on work often overlooked, the novel broadens conceptions of worth and success, challenging assumptions about status, virtue, and the rights of those who serve.

Approached today, the novel rewards patient attention with a vivid portrait of a household tested by circumstance and held together by character. Readers will find a humane seriousness that balances hardship with resilience, inviting reflection rather than simple judgment. The narrative sustains suspense through moral uncertainty more than plot shocks, making its satisfactions cumulative and deeply felt. As an example of Victorian domestic fiction, it offers both a window into its era’s values and a mirror for ongoing concerns about care, fairness, and mutual dependence. Mistress and Maid thus remains a compelling study of everyday ethics under pressure.

Synopsis

Set in mid-Victorian England, Mistress and Maid traces the fortunes of two genteel women living quietly on narrow means. Respectable but precarious, their household depends on careful economies and steadfast habits. To keep order and preserve appearances, they resolve to take a servant, though doing so strains their purse and invites scrutiny from well-meaning relatives. The narrative begins with practical concerns—rent, work, and the polite rituals of a small town—establishing a domestic stage where character is tried more than spectacle is sought. The story positions home life as the arena of trial and support, preparing the reader for tests of duty, trust, and endurance.

They engage a young maid, inexperienced but eager, recommended through charitable channels. Her arrival alters the rhythm of the house: new responsibilities must be taught, boundaries drawn, and patience exercised on all sides. The mistress, sensible and quietly resolute, balances kindness with authority as she trains the girl in the small arts that sustain a family. Early mistakes—breakages, tardiness, and misunderstandings—provoke comment from neighbors and kin, who fear disorder will invite harm. The hire is both a necessity and a risk, but the women persist, believing that labor honestly guided can steady fortune and secure respectability despite their shrinking income.

Fragments of the maid's past emerge: hardship, scant schooling, and the uncertain hopes of one who has known few advocates. The mistress recognizes both vulnerability and promise, and she insists on principles—truthfulness, thrift, and modesty—that form the ethical spine of the home. Gradually, the household begins to move as one body. The maid learns to keep accounts, to guard confidences, and to carry herself with self-respect; the mistress learns when to overlook and when to correct. Gossip rises and falls in the street, but the private bond strengthens, hinting that loyalty grown in service can be as firm as kinship.

Beyond the threshold, social forces press in. A prudent relation urges strategic alliances; a courteous gentleman, closely connected to their circle, observes the mistress with increasing regard. Visits, church-going, and seasonal gatherings reveal the fragile line between friendship and expectation, admiration and obligation. The mistress keeps her footing by maintaining her independence, even as affection and duty begin to intersect. Meanwhile, the maid learns the subtler tasks of service—discretion in speech, presence without intrusion, and a watchful eye when small oversights threaten to become large embarrassments. The world outside the parlor tests the balance the women have built within it.

A sudden financial alarm disturbs their carefully measured life. Income falters; debts sharpen; the possibility of losing their dwelling is quietly discussed. Unaccustomed burdens fall on the mistress, who takes on additional work, and on the maid, who extends her efforts beyond what was first asked. Strain exposes weak points: a misplaced key, an unguarded letter, a confidence shared at the wrong moment. What might have become a scandal is contained through prompt confession and steady truth. Yet the household's position remains uncertain, making plain that honest conduct, though necessary, cannot alone shield them from the consequences of misfortune.

Illness enters the home, and time slows to a vigil. The mistress, worn by anxiety, depends on the maid's patience and dexterity; roles of authority soften into mutual care. The sickroom scenes reveal character under pressure: faithful service, calm decision-making, and a refusal to barter integrity for relief. Offers of help come from acquaintances with varying motives. The maid confronts a private dilemma involving a confidence that could avert trouble but expose another to blame. The choice between silence and speech is measured against the household's rule of plain dealing, and the cost of each path becomes painfully clear.

Clues accumulate around their wider connections: business accounts that do not tally, letters hinting at obligations long ignored, and the quiet involvement of the gentleman who has steadily gained the mistress's esteem. Without turning the women into spectators, the narrative admits careful assistance from friends who respect their autonomy. The maid's earlier life proves more entangled with the present than she knew, and her candor helps unravel confusion. A turning point arrives when hidden relationships are acknowledged and responsibilities are placed where they belong, removing a weight that has bent the household for months and bringing the characters to open choices.

Consequences follow swiftly. Misunderstandings resolve into plain facts; the financial question finds a lawful settlement; and reputations, threatened by whisper and appearance, are publicly righted. The maid's constancy is recognized without condescension, confirming her worth beyond the measure of wages. The mistress, having traversed hardship with composure, accepts what future has been fairly earned, neither trading independence for comfort nor pride for sympathy. The outcomes accord with the novel's moral terms, where labor, truth, and affection have enduring claims. While personal destinies take a decisive turn, the telling preserves their privacy, leaving the particulars to unfold within the home.

Taken together, Mistress and Maid presents a household as a moral workshop, where class divides are narrowed by shared responsibility and character tested by ordinary trials. It emphasizes the dignity of steady work, the justice of clear dealing, and the healing power of loyalty freely given. Without relying on grand reversals, the story affirms that quiet courage can sustain lives through illness, debt, and scrutiny. The title's pairing proves mutual: mistress and maid serve each other's good, each enabling the other's growth. The closing sense is one of earned stability and humane order, with possibilities left modestly but securely open.

Historical Context

Set in mid-Victorian England, the narrative unfolds within a provincial middle-class household closely tied to the rhythms of a rapidly industrializing society. The time frame aligns with the 1840s–1850s, when London and growing towns in the Midlands and North shaped national culture, yet domestic life remained the primary arena for women and servants. Anglican moral codes, the cult of respectability, and the ideal of the orderly home govern relationships in the story. Rail travel, the postal system, and expanding commerce subtly widen horizons while reinforcing the household as a microcosm of class negotiation, duty, and economic dependence.

The domestic service system was the largest female occupation in Britain and decisively shapes the book’s world. The 1851 census recorded roughly one million domestic servants across England and Wales, with young single women predominating; by 1871 the number exceeded 1.3 million. Hiring routes included provincial “mop” fairs and urban registry offices, while live-in arrangements folded wage labor into moral surveillance. Typical annual wages ranged from about £8–£16 for housemaids and £12–£26 for cooks, alongside board, uniforms, and small perquisites, but hours were long and privacy scant. Law reinforced the asymmetry. Under Master and Servant law (notably the 1823 Act), breach of contract by servants could be treated as a criminal matter until late-century reforms, and the Servants’ Characters Act of 1792 criminalized forging or knowingly giving a false reference, making the “character” both a gatekeeping device and a weapon. Conduct manuals culminating in Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861) codified the mistress’s managerial authority and the servant’s graded obedience. The novel mirrors these structures: it treats the household as a workplace governed by trust, documentation, and reputation; plots hinge on hiring, dismissal, and testimonial integrity; and the mistress’s moral leadership is tested by the ethical management of dependent labor. Through attention to wages, status, and the precarious power of references, the story interweaves domestic affection with legal and economic compulsion, dramatizing how Victorian homes depended on a disciplined, feminized labor force.

Debates over women’s paid work and the governess question formed a prominent social backdrop. Queen’s College, Harley Street (founded 1848), and Bedford College (1849) sought to professionalize female education, while the Governesses’ Benevolent Institution (1843, with royal patronage from 1849) offered relief and pensions. Middle-class women increasingly took positions as companions, teachers, or shop assistants to support families after commercial failures or bereavement. Dinah Mulock Craik’s own essays, notably A Woman’s Thoughts about Women (1858), advocated respectable employment for women. The novel reflects this climate, presenting female economic self-reliance and the ethics of paid service as dignified, if fraught, paths within rigid respectability codes.

Industrial urbanization prompted sanitary reform that reshaped household practice. Edwin Chadwick’s 1842 Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population and the Public Health Act of 1848 promoted drainage, clean water, and waste removal; the Great Stink of 1858 in London dramatized the stakes of reform. Servants often shouldered the practical labor of cleanliness—hauling water, scrubbing, and managing refuse—making hygiene a workplace issue. The book’s attention to order, health, and routine mirrors an era when domestic respectability was inseparable from sanitary discipline, and when a mistress’s competence was measured by the visible cleanliness and healthfulness of her home and dependents.

Railway expansion and communications revolutions altered mobility and oversight within domestic life. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opened in 1830; the 1840s Railway Mania and the 1846 gauge standardization knit regions together, while Rowland Hill’s Penny Post of 1840 made letter-writing cheap and rapid. These innovations eased the movement of servants seeking posts, enabled surprise visits and inspections, and intensified the circulation of news and rumor that could make or break reputations. The novel’s episodes of travel, timely letters, and swiftly transmitted misunderstandings reflect a world where intimacy and authority are recalibrated by speed, distance, and documentary traces.

The Crimean War (1853–1856) reshaped ideals of feminine service, discipline, and compassion. Florence Nightingale’s 1854 mission to Scutari and Mary Seacole’s independent efforts in the Crimea, widely reported by The Times, created new public models of female duty, cleanliness, and administrative rigor. After 1856, sanitary and nursing reforms filtered into civilian life, elevating the moral and practical value of ordered care. The novel echoes these currents by valuing conscientious, skilled service and the mistress’s managerial stewardship, presenting domestic labor not as mere drudgery but as a vocation aligning personal character with public-spirited ideals of organization, thrift, and benevolence.

Victorian marriage and property law framed women’s dependence and vulnerability. Under coverture, a married woman’s legal identity merged with her husband’s; the Custody of Infants Act (1839) and the Matrimonial Causes Act (1857) introduced limited reforms, with broader property rights coming only with the Married Women’s Property Act (1870) and later 1882. These shifts were debated throughout the 1850s–1860s. Servants and lower-middle-class women remained especially exposed to dismissal, slander, and sexual exploitation, with few remedies beyond reputation and patronage. The novel exposes these pressures by linking livelihood to moral surveillance and showing how a single accusation or lost reference could imperil a woman’s future.

By staging the intimate negotiations of authority, trust, and labor inside a respectable home, the book critiques the period’s asymmetric power structures. It reveals how the rhetoric of Christian benevolence and domestic harmony masked contractual coercion, surveillance, and economic precarity for women in service and for gentlewomen compelled to work. The emphasis on characters and testimonials questions a culture where paperwork could outweigh truth, and class could override merit. The narrative unsettles complacent middle-class management by demanding ethical stewardship, fair wages, and due process, thereby exposing the hidden politics of the Victorian household—its class boundaries, gendered hierarchies, and legal inequities—as matters of public justice.