23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Many railway modellers include an engine shed somewhere on their layout. However, all too often the shed is squeezed into a quite improbable location and is little more than a place to 'park' engines when they are not in use. This well-illustrated and comprehensive book, written by an experienced railway modeller, helps even the beginner to develop a far more realistic approach and to capture the unforgettable grimy but exciting atmosphere of the locomotive shed in the steam era. The book covers all types of engine shed from the branch line sub-shed to the main line motive power depot, and discusses research, planning, the building process, readily available materials and simple tools. It goes on to explain how to obtain the very best from kits, how to site and operate sheds, and how to make them look authentic. It demonstrates the construction of over a dozen kits, including off-the-shelf kits and the newest computer downloadable kits, and shows the modeller how to create special dioramas depicting the whole shed scene and how to scratch-build complete sheds, including coal stages and other infrastructure. With further advice for those with a limited amount of space, and 'top tips' throughout, this is essential reading for modellers of all abilities who wish to incorporate a realistic locomotive shed of the steam era into their layout. Well illustrated with 323 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Modelling Engine Sheds

& Motive Power Depots

OF THE STEAM ERA

TERRY BOOKER

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© Terry Booker 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 115 4

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it. If in doubt about any aspect of railway modelling skills and techniques, readers are advised to seek professional advice.

CONTENTS

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE: SMALL ENGINE SHEDS

CHAPTER TWO: SCRATCH-BUILDING A SINGLE-ROAD ENGINE SHED

CHAPTER THREE: LARGER TWO-ROAD SHEDS IN THE STEAM ERA

CHAPTER FOUR: THE MPD THROUGH THE YEARS

CHAPTER FIVE: BUILDING THE NORTH LIGHT SHED AND COALING STAGE

CHAPTER SIX: ANCILLARY STRUCTURES

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE MPD IN THE STEAM ERA

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE MPD IN PRESERVATION: THE EARLY DAYS

CHAPTER NINE: THE MPD IN PRESERVATION: THE STEAM CENTRE

APPENDICES

INDEX

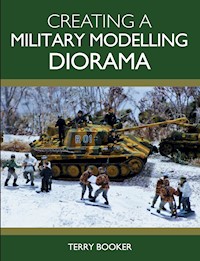

PREFACE

One of the more difficult tasks facing the railway modeller, or indeed the model railway author, is to try to define the exact time at which the model is set. It’s possibly fair to say that this problem is unique to our hobby. Our colleagues who model military subjects certainly have no such difficulties: if their diorama represents the Battle of Hastings, the Battle of the Bulge or the Battle of Gettysburg, then their definitions of time and place are predetermined. Even the Battle of Britain can be pinned down to a matter of weeks and specific locations. The same is true of their single models, where the tank or aircraft belonged to a particular unit or even to a particular officer.

It is not so easy for us who strive to produce realistic models of the steam or early diesel periods. In most cases, though not all, even our locations are hypothetical and our time-span is often defined in years … if not decades. This is not made any easier by the simple fact that our chosen subjects were in a constant state of evolution. Many engines reached the scrapyards of the 1960s looking much as they did when they left the factories a half-century earlier, but in the intervening years they may well have worn a dozen or more different liveries. This fact is an undoubted boon to ready-to-run (r-t-r) manufacturers, who can produce scores of ‘new’ models from their original investment.

These anachronisms are almost inevitable and I must admit that on my own layouts, which ostensibly are set in the decade from 1945 to 1955, Southern engines can appear in pre-war Maunsell livery, Bulleid Malachite Green, early BR blue or post-1956 Brunswick Green with the later crest. Nor are things any better with my ex-GWR, LMS, LNER and BR Standards.

Fortunately most engine sheds tended to look pretty much the same throughout their lives, give or take the odd coat of paint. For this book, at least, we can let the description ‘Steam Era’ span the whole period from the last years of the Big Four up to the last wisps of steam at end of the 1960s. Indeed, we’ll go even further by giving our motive power depot (MPD) a new lease of life as a contemporary ‘Steam Centre’, where you can feature your locomotives in whatever livery you choose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

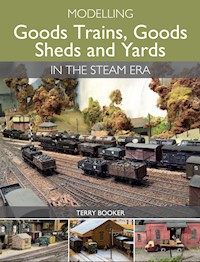

It is not long since I was grappling with the problem of what to say in my previous book on modelling goods trains. The difficulty is compounded by the need to avoid repeating myself even while thanking those same kind individuals. However, I must begin by expressing my gratitude to my publishers at The Crowood Press who bravely commissioned this second title almost before the first manuscript had been delivered. Next I cannot allow the immense tolerance, generosity and encouragement of my late parents to pass unacknowledged. Even when times were hard they never failed to foster my love of steam railways and my passion for model-making. How lucky can one get to then have a family of one’s own who continued to support ‘the old chap’ in both these hobbies. My poor wife and my two fine sons have been dragged from one end of the country to another in pursuit of steam. Even our continental holidays meant dampf on the Rhine and not loungers on the Riviera.

For this book in particular I must thank those companies who kindly contributed some of the kits and bits for the many projects, notably Dapol, Scalescenes, Langley, Freestone Models, Sankey Scenics and Model Railway Scenery. The assistance of the archivists who have provided the invaluable, and duly credited, images has helped to anchor the work firmly in the long-past steam era. Finally, and as before, I would like pay tribute to the scores of photographers, authors and publishers who keep us engrossed as readers and inspired as modellers.

(All photographs are the Author’s unless otherwise credited.)

INTRODUCTION

Engine sheds are often referred to as ‘Cathedrals of Steam’, usually by romantically inclined authors who never had the dubious pleasure of having to work within their dark, dank and dangerous environments. It is true that the shafts of hazy sunlight filtering through the smoke-begrimed windows, recorded for posterity by talented cameramen, sometimes resemble the heavenly beams glimpsed in our magnificent churches, but there the resemblance ends. Just read a few chapters of any engineman’s autobiography and any ecclesiastical images will be quickly dispelled. The sheds were Victorian in their origins, Victorian in their practices and the standards of health and safety were certainly Victorian. Our fathers and grandfathers were as unlike us as a Patriot is to a Pendolino. They didn’t just endure these primitive working conditions; they thrived amid them and took enormous and justifiable pride in being a part of that elite community of railway servants.

This is the epitome of the ‘Cathedrals of Steam’ shot, as a veteran pre-grouping 4-4-0 enjoys its twilight years.BEN BROOKSBANK AND LICENSED FOR REUSE UNDER THIS CREATIVE COMMONS LICENCE

In the following chapters I hope to apply some of the creative ethic that is an integral part of the works produced by our fellow military modellers. Irrespective of whether they produce dioramas, set pieces or single subjects, there is always an underlying feeling of ‘tribute’ to those who fought there or who drove or flew the original machines. That is not to say that they are in any way either pious or precious about their efforts. They simply set great store in their research and do their best to capture some of the atmosphere alongside the undoubted accuracy of their model-making. Without wishing to over-romanticize things – and I admit to being a fairly frequent military modeller myself – it’s a bit like a handshake or a salute back in time. Perhaps it’s a way of saying ‘thank you’ and keeping the memories alive.

In a short poem Sir Christopher Foxley-Norris described a Battle of Britain pilot as ‘a common, unconsidered man, who, / For a moment of eternity, / Held the whole future of mankind / In his two sweating palms – / And did not let it go’. I would like to think that bygone generations of enginemen and shed staff merit a similar outlook from railway modellers. They too were ordinary men whose lifetime’s work it was to constantly maintain the nation’s arteries, in all weathers and with machines that were at best primitive and at worst clapped-out. They deserve our respect and admiration and, if we can convey any of this on our layouts, the better modellers we will be.

RESEARCH

One of the great things about engine sheds is the plethora of potential research information. I accept that field research is a bit of a non-starter since most sites have long since been buried under bypasses, car parks or supermarkets. Those that do survive, like Didcot, Carnforth, Tysley or Swanage, are either very much changed and ‘sanitized’ or, as in the latter case, are generally inaccessible. Desk research, however, has never been easier. It can be roughly subdivided into three broad groups: technical, inspirational and anecdotal. The first category covers reference works that show the layout of the sheds, their key facilities and the site plans; they also often include the locomotive allocations at various times. Most of these are based on the individual BR regions and may include one or more photographs of the depot at some point in its history. The second category includes the innumerable ‘on-shed’ photo albums, which are also generally presented by region and are sometimes dedicated to just one establishment, usually a major motive power depot (MPD). It goes without saying that the shed buildings are often little more than the backgrounds to their resident or visiting engines. The final group comprises the many autobiographies from the footplatemen and sometimes from the Shedmasters. These are essential reading for anyone who wants their model shed to ‘feel’ like the real thing. The earlier chapters usually provide better reference points since enginemen, like everyone else, started at the bottom and their working lives then rarely took them much beyond the confines of the shed yard.

Steam as I remember it: a pair of ‘Caledonian’ blue Kings pose alongside a newly built BR(W) Britannia. All three are long-term performers on the author’s ‘Wessex Lines’.

It is difficult to know how best to guide readers along the path of research. If we were discussing it within an academic environment it would be considerably easier, since one could reliably expect that all the students were at roughly the same point on the learning-curve. In this particular context, however, no two readers will share the same levels of experience, the same levels of skill or have layouts at the same level of development. In order to be fair and to offer something useful to the newer entrants to the hobby, any advice must begin at the beginning, even though that may risk being too simple for the more experienced modellers. The reverse is, of course, equally true. If everything is pitched at a level to match the aspirations of those who are already into the more advanced aspects of modelling, it inevitably means ignoring the needs of the newcomers.

It is indeed a dilemma, but with due apologies to the older hands, who can skip the more basic techniques, I’ll start by setting out some of the initial guidelines regarding research. The first of these is that it should, above all, be a pleasurable experience and not a tiresome chore that keeps you away from modelling.

POSSIBLE SCENARIOS

Most modellers probably have at least a vague idea of the sort of layout they would like to build and it is equally likely that there is an engine shed somewhere within that idea. Another assumption is that the prospective layout will be largely hypothetical in location and probably quite loose in its time-frame. Now there’s nothing wrong with returning from the nearest model shop with an armful of track, a few buildings and some engines and rolling stock, shoving it on a baseboard and ‘playing trains’. The ultimate aim, after all, is to simply enjoy watching the trains running, no matter how sophisticated our layouts.

A few hours of research, however, can transform those rather haphazard beginnings into the start of a well thought-out model railway. It is immaterial whether our ambitions are constrained by a lack of funds, time or space, or whether we can confidently envisage building a major layout. The branch-line terminus or main-line junction will both be the better if they originate from some prototype research rather than just a convenient way of filling the available space.

I like to think of research as a sieve for ideas. We start with a very coarse screen, just browsing through all the available sources – print or internet – eliminating that which doesn’t appeal or is not really relevant to our original idea. Anything that gets through the sieve should then help to give a better idea of some aspect of the following key elements:

Swindon’s running-sheds on a Sunday morning in the early 1950s.BEN BROOKSBANK AND LICENSED FOR REUSE UNDER THIS CREATIVE COMMONS LICENCE

Geographic location: This might be Home Counties commuter belt, Midlands industrial, North Country mining, Welsh mountains, Wessex rural or something else.

Parent company/BR region: The choice of LMS, LNER, Great Western, Southern or BR (Scottish) will obviously be influenced by the chosen location.

Size of shed/operations: This is where reality impinges on the dream. What we can actually build will be governed by the space available, which in turn will govern the level of operations that we can envisage. This is where you must decide between a branch line or a main line.

Allocation: This is probably the most contentious issue facing most modellers: do we try to find a shed that can accommodate the engines that we want (or already own) or do we limit our choice of motive power to that which would be the most likely to be allocated? My head of course says the latter, but my layout proves the former!

This first trawl through the various sources should, when put together with your original ideas, enable you to come up with the vital foundations for a satisfying layout. It will, of course, need some refining but there is now sufficient information for a viable back story and perhaps for a few tentative track plans to see what you might be able to fit into the allotted space. I would advise you to get into the habit of writing things down. It need not be anything elaborate; just a simple ring-binder and an A4 refill pad will suffice. Use the back pages to jot down ideas and references, perhaps adding some photocopied images, and use the front of the folder for your back story and any essential elements. If you’d prefer, the same exercise can be done on your keyboard. Your back story will already have combined the answers to those previous questions: the probable location, the company or region, the size of the shed and the likely traffic needs, and finally the necessary engine types. Now you can start the more focused and finely filtered research.

It’s best to discard any sources that are no longer relevant to the plot. Wherever possible concentrate your searches on those works that are specific to your chosen location/region or at least feature them to a significant extent. The two areas where you can justifiably stay broadly based are track plans and autobiographies. The former may give you a near-perfect track plan from Devon that ban easily be transferred to north Northumberland, while the experiences of an engineman in Leeds will be little different from those of a GWR man at Laira.

MODELLING THE SHED

At the risk of making yet another assumption, I would suggest that the vast majority of layouts rely upon kit-built sheds rather than on scratch-built examples of specific prototypes. We are fortunate that the current offerings from the trade are both many and varied; indeed, if one then adds the ease with which they can be extended and altered, it almost eliminates the need to even consider the scratch-built option.

In the following chapters we will be constructing many of the available kits from the very smallest up to those better suited to the larger MPDs. Some of these are based on actual prototypes, but the majority are what might be described in ecclesiastical terms as ‘non-denominational’, or more commonly as ‘one size fits all’. Any of these can be quickly re-regionalized with the simple application of new paintwork in the appropriate livery. Most steam sheds, however, rarely saw a paintbrush once they were commissioned and several decades of smoke and soot rendered them in the same smut-covered colours from Penzance to Inverness.

Any ‘shed’ is going to be much more than just the building itself. The shed-yard and all the other essential facilities are key factors in creating a realistic and ‘railway-like’ model. They were as varied as the sheds in both size and presence: one would not expect to encounter mechanized coaling plants and locomotive hoists at the end of a rural branch line. Similarly, no large MPD would expect its coalmen to refill a score or so tenders working with just a shovel off a sleeper-built stage.

Sherborne shed on ‘Wessex Lines’ is the author’s rather reduced interpretation of an MPD. It’s a scratch-built exercise based on a single small image of the former LSWR shed at Salisbury.

Steam on shed in the twenty-first century. This ex-Db 2-6-2 awaits its turn of duty at this large and very popular steam centre in the Netherlands.

All of these facilities will be looked at in some detail and as appropriate to the type of shed and the scale of its activities. The emphasis will focus on the available kits, but the various dioramas will also include a degree of scratch-building and adaptation. It also goes without saying that no shed scene would be complete without its allocated locomotives, the enginemen who drove them and the small army of shed staff who kept them on the road. That thought brings us neatly back to where we began.

I suspect that there are very few of today’s modellers who had access to a shed on a normal working day, apart from the elite group of former footplate-men or shed staff who are still active in the modelling world. Some of the older generation of spotters might possibly have enjoyed the occasional official weekend visit to a shed, but that is not the same. Lastly there is that very small minority of former enthusiasts who may have worshipped in these ‘cathedrals of steam’ on a weekday (if the noble art of ‘bunking’ a shed without being caught can be described as a religious experience).

It was always the men who worked them, however, that gave them their true status and character. It is not enough to present them as shiny plastic drivers, acrobatic ever-shovelling firemen and labourers in neat overalls. They were ordinary men going about their daily routines and should be portrayed as such. Yet it was those same men who gave us ‘linesiders’ so many treasured memories and have since gone on to inspire generation after generation of modellers, many of whom were not even born when the last sheds were demolished.

Ensuring that your modelling is truly ‘railway-like’ will help to provide a fitting tribute to the fast-vanishing family of steam-era enginemen.

CHAPTER ONE

SMALL ENGINE SHEDS

THE ENGINE SHED IN THE STEAM ERA

Most modellers, even those who are still only just emerging from starting with train sets, like to include an engine shed on their layouts, even if it this may have little purpose beyond being somewhere to park any spare locos when they are not in use. This has always been the case, even in the days when the choice of sheds was limited to the single-road plastic kit from Airfix or the larger two-road card version from Bilteezi. Many layouts in the 1960s were graced by these models, often using two, three or even more kits combined into a larger structure. Today, however, there are far more choices on offer in both kit form and as ready-to-site models from Bachmann and Hornby.

If we wish to stick to the intention of achieving truly ‘railway-like’ and prototypical appearance and operations, which I outlined in my previous book on modelling goods trains, we must delve deeper into what the steam-era shed was all about. Fortunately, there is plenty of archive material available in books, magazines, on DVD and via the web. This can range from major titles featuring all the sheds within a specific BR region (with photos, track plans and even stock lists) to the autobiographies of enginemen or shed staff that deal with life at one particular depot. To these can be added the ever growing library of steam albums, some of which are specifically shed orientated and most of which include at least a handful of shed shots. Film archives, lovingly remastered onto DVDs, can be an endless source of information and inspiration. These are able to capture shed life almost minute-by-minute with locos arriving, being serviced and going off-shed, all amid the atmospheric smoke and smother that epitomized the steam-era depot.

The small shed at Marlow, Buckinghamshire. The fireman is loading the bunker of his 14xx tank directly from the steel-open. This is an unusual practice but would be interesting to model. Note the familiar ash heap and that the coal is in the form of briquettes. The very prominent notice warns of the low headroom.AUSTIN ATTEWELL

Much Wenlock shed, seen here in GWR days, is a typical Victorian structure sturdily built of local stone with considerable decorative work. Note the cramped interior, the massive doors and the water tank at the rear of the shed. The water tank could also be located over the entrance.COURTESY STEAM MUSEUM OF THE GREAT WESTERN RAILWAY SWINDON

Irrespective of its size, the loco shed, like the goods shed and goods yards featured in my earlier book, shared many common features and common purposes throughout the land. Locomotives could be housed there under cover between duties. Resident or visiting engines could replenish their coal supply and take on water. In many cases engines could be turned on a turntable or make use of a convenient ‘triangle junction’. Even the smallest branch-line shed had the facility to drop the fire, dispose of the ash and clinker, and carry out the vital oiling and some basic repairs. Larger sheds would provide a far wider range of facilities, such as boiler wash-outs, wheel-drops, hoists, repair shops and mess-rooms. Something that most of them shared was that they were definitely only for the staff, with absolutely no official public access. They would often be some distance away from the end of the platform and any waiting trainspotters. Even those that were temptingly close, such as Bournemouth or Bristol Bath Road, remained tantalizingly inaccessible to the enthusiast.

Sheds were universally, and unavoidably, dirty and potentially dangerous environments in which to work. Irrespective of the enthusiasm of even the most autocratic shed foreman, little could be done to keep it and its environs clear of the inevitable muck and clutter resulting from round-the-clock operations. All of this can present a real challenge to even the most experienced of modellers. It stretches one’s capabilities as a scenic expert to the limits. Thatched country cottages, trees, fields, ponds and fully detailed working farmyards are much easier to model than any attempt to capture accurately the appearance and atmosphere of a busy steam shed. In later sections we will show some of the ways that this can be overcome, but first it is worth examining the principal facilities and key features. Once again the simplicity of a list is the easiest way to approach the subject from the modeller’s angle.

Tetbury shed is more typically Great Western in appearance, being of brick construction and with far less detailing. The coaling stage has a shovelling platform in front of the storage area and is built back into the steep hillside.AUSTIN ATTEWELL

Tetbury again, but this time from Prototype Models and here representing the branch shed at Watlingford on the author’s ‘Wessex Lines’. The small coaling stage was built to fit from balsa strip to replicate the usual sleeper constructions.

Regionality: This can be defined either as the originating company, a BR region and/or a particular geographic area. All of these factors will influence to some extent the design of the buildings and the materials likely to be used.

Size and role: These factors are interdependent and will be governed to a large extent by the back story to the layout and the available space. If you are modelling a typical branch-line terminus, a single-road shed housing one or two small locos will be adequate. If you have more grandiose ambitions and are assembling a secondary or main-line layout, then you can justify a multi-road shed with full facilities and a stud of twenty or so suitable locomotives. To do this, however, the available space will have grown from a square foot to at least a square yard.

Siting: Where to place your shed needs careful consideration. Bigger sheds indicate more intensive operations, for which you will require easy physical access. Ideally it should be away from your passenger platforms and, if possible, also quite separate from the goods yards.

Shed design: There is a wide range options here that can be summarized into three principal areas:

Straight sheds, which may have either an end-wall or through tracks;

Hipped roof or transverse north-light versions;

Offices, messing, stores, workshops and so on, all of which may be built-in or separate structures.

All of these will be examined in later sections.

Basic facilities: Essential facilities include a coaling point, watering point, inspection pit, ash pit, workbench, stores, and mess-room. (The last of these may be no more than a grounded van body or a small lean-to attached to the main building.)

Extended facilities: These will apply to larger sheds: a sand furnace, workshops, mechanized coaling, multiple watering points, an ash-shelter and coal stack (both immediate post-war only), offices, loco hoist, wheel-drop, cycle racks or sheds and a turntable. The bigger the shed, the more of them they will have.

Personnel: Even a small shed is likely to have two or three sets of footplate crew: three sets per loco is a safe bet for most depots. If there are two or three allocated engines, then the non-footplate staff might run to a shedman and perhaps a resident fitter. Larger sheds will see a larger number of crews either preparing or disposing of locomotives. Crews would book-on to allow at least an hour preparation before they were due off-shed. To these can be added cleaners (in teams of four) and the shed staff themselves. A reasonably large shed, such as Reading, with about ninety locomotives, would have had close to three hundred crews and more than fifty shed staff. Many of the latter would be working in civilian clothes rather than any official dress. In the 1950s a considerable amount of hard-wearing, ex-service clothing was in evidence. Loco men would generally be in well-washed and faded overalls. The GWR men wore jacket and trousers on the footplate, but these were not always regulation issue.

An excellent example of how the original builders dealt with the modeller’s problem of lack of space. This is the shed at Kingsbridge, complete with inspection pit, coaling stage, ash heap and water tank, squeezed into the narrow gap between the platforms and the hillside.AUSTIN ATTEWELL

Surfaces: By the mid-1950s most sheds had been in daily use for more than a century. In the busiest areas the mixture of crushed ballast, cinders, ash and coal dust had built up to at least sleeper height, leaving only the chairs and rails remaining above ground level. These created the inevitable hazards for crews preparing locos within the wet, windy, stygian gloom of a winter’s evening, illuminated only by the flickering flame of a flare lamp. In many instances even the sleepers in the four-foot had disappeared and the accumulation of general detritus had reached the top of the rails. The uneven ground meant that puddles were numerous, caused by the engines themselves as well as by the weather. In the winter months the whole shed yard would appear to be a blend of almost shiny greys and blacks, while in the summer the tones would be the softer, paler and with much dustier greys and oily browns. The areas around the coaling stage were coated in coal dust all year round, while the disposal roads and ash pits would be covered with a liberal coating of almost creamy-white ash and char.

Debris: More of this would be found later in the selected period as the railways struggled to find staff, especially among labouring grades. Typical junk would include piles of brake-blocks, boiler tubes, fire-bars and broken fittings around the workshops and the shed walls. Around the yard would be brooms, buckets and bent discarded fire-irons. Sheds needed several different grades of oil, so multi-coloured barrels, full and empty, could be seen piled up awaiting collection. In the earlier years of the chosen period morale and staff levels were that much higher: pride in the job and the sense of being ‘company servants’ generally led to a much tidier environment.

Another of the author’s models, this time inspired by the timber-built shed at Fairford. The actual carcass is the old Airfix (Dapol) plastic kit, but it has been completely covered with planking and re-roofed with tile-paper. The crew accommodation is an ancient ‘Toad’ brake van and the water tank is a Wills kit with coaling platform beneath. Some scrap plastic stonework helps to tie the scene together.

Track layouts: These are infinitely variable, from the ultimate in simplicity with just one siding serving a single-road shed at a branch terminus to the maze of tracks and point-work needed for a major MPD. Every track plan will be unique, but there are still some aspects you may wish to consider. Wherever possible you should endeavour to have separate access to the ash pit, coal stage and turntable, as distinct from the shed and storage roads. This enables visiting locos to be serviced without impacting on shed movements. Try also to have spare trackwork even when most of your allocation is at home. Shed yards rarely looked full of locos except overnight or at weekends, and even then some movements were still possible.

These general pointers may help to guide your eye as you study your various references and they should give you plenty of ideas for your project build. As always there is much to note and probably too much to remember. My own technique when researching is to have a notebook or scrap pad handy to jot down, or even quickly sketch, any items and ideas that could prove useful when building and detailing the sheds.

In the subsequent sections many of these features will be re-examined in more detail. In particular we will look at their relevance and suitability for the specific projects and how they might best be replicated in miniature.

SMALLER SHEDS

The most appropriate description of the first subject we will tackle is a small single-road engine shed, usually found at the end of a branch line or at sites with a specific role for no more than one or two engines, for example at the foot of a bank.

Most of this country’s railways began life as pretty small affairs. They were promoted in the main by local merchants and industrialists seeking to get raw materials in and finished products out more cheaply, quickly and reliably than by canal or turnpike. Even when the steam railway and locomotive haulage replaced horse power it still needed to be stabled, fed and watered in much the same way. The locomotive shed, or what might be described in Victorian terms as a ‘commodious engine-house’, would be the first structure to be built and brought into use.

Its purpose and the way in which it was worked would, unlike the locomotives it housed, remain largely unchanged from the mid-nineteenth century to its probable demise more than a hundred years later. The actual design of the sheds was very simple and their construction pretty basic. Structurally they were little more than three tall, solid walls with the fourth containing the entrance doorway. The roof was most likely a straightforward pitched version, although north light and hipped versions were not uncommon. As a rule the shed would feature large windows and a system of roof vents to allow smoke and steam to escape.

The general layout of the shed yard was infinitely varied depending on the immediate geography surrounding the site, which could range from wide, flat and open fields to the constraints of being squeezed against the face of a cliff. The sizes of the actual sheds themselves were equally variable. One of the main reference books on the subject, E. Lyons’s An Historical Survey of Great Western Engine Sheds, 1947 (Oxford Publishing Co., 1974), notes that there were no fewer than eight different widths for single-road sheds, while they varied in length from a diminutive 40ft (12m) to more than 100ft (30m) for the largest structures. Out of the forty-six examples I examined in search of some common footprints, the best I could come up with was just five that measured 20 × 60ft (6 × 18m). Stretching the width slightly to 22ft (6.7m) yielded just two more examples. In modelling terms, those dimensions translate as 80 × 240mm, or nearly 10in long, which makes it a hefty item to squeeze into the often restricted available layout space. The two models selected to begin the projects will be of more modest dimensions.

Building materials would vary as much as would the actual designs. In most cases the choice would be locally sourced bricks, but if the builders had access to cheaper dressed stone from a nearby quarry, then that might be the preferred option.

The Prototype kit of Sidmouth shed on the Southern Region. Here it is home to the resident banking engine, a kit-built 72xx 2-8-0 tank, on ‘Wessex Lines’.

It is quite common to refer to some major sheds as ‘cathedrals of steam’. The railway architects, like their colleagues in industrial and civic architecture, were strongly influenced by classical and ecclesiastical buildings. That being the case, the single-road engine shed could well be termed a ‘chapel of steam’. Certainly their simple robust design closely resembled the growing number of rural and suburban chapels. On those few occasions where sheds were built of timber or corrugated iron, the resemblance to the once familiar ‘tin chapel’ could seem even more marked.

These simple structures alone, however, would not be enough. The locomotive could at least be securely locked away when not in use, but the iron horse was then, and is now, a greedy beast and requires regular and ample supplies of coal and water. It also needed to be repaired and maintained, so the shed immediately became a small self-supporting facility with adequate resources on hand to keep the locomotive in profitable daily work.

Internally there would be a workbench with vice and enough tools to keep the wheels turning. There would probably have been a small forge, anvil and water trough, cupboards for storage and a notice-board. It would have somewhere secure for storing oils and lubricants, as well as a container for sand. Among the more readily available items would be the loco’s oil lamps and undoubtedly some flare-lamps (like Aladdin’s and still in common use in the 1950s). Externally three features would dominate, with first a stage or dump and perhaps a rudimentary hoist for loading the coal. Second there would be a water tower close enough to the track to fill the loco directly. This may also have had a pump housed either adjacent to it or located within the supporting walls. The final visible feature would be the dump for ash and clinker. Somewhere within that small yard area, probably outside the shed doorway, would be the loco pit, where ashes could be dropped or works carried out to the underside of the engine.

What of the staff? Obviously there would be a driver, although from the dawn of the railways to the demise of steam he was more properly known as the ‘engineman’. His colleague, then and now, is the fireman. They were responsible for the resident locomotive and at the smaller sheds they would probably have to carry out the preparation and disposal themselves. When a second and perhaps third locomotive was allocated, the company might recruit a couple of general ‘shed men’ to take over some of the less pleasant or technical tasks. They would be dropping the fire, emptying the ash pan and smokebox, ensuring that the bunker or tender was replenished and lighting up the engine before the shift.

Access to the shed via a turntable was fairly unusual: it is also very difficult to reproduce in model form. These turntables were quite small and there seems to be nothing suitable in either ready-to-install or kit versions. This example is still in use on the Swanage Railway.

Originally all these men would live in easy walking distance of the shed, as some of their shifts could be long and usually irregular. Once this initially simple shed became part of a proper station complex with goods and passenger facilities, the respective companies would often build railway cottages on an adjacent plot. This would almost certainly be the case if the shed was in a more rural location and often well beyond the outskirts of the town it served. As one might guess, such were the huge variety of locations, the different roles of the lines themselves, and the differences in traffic and timetables, that any description of a typical working day is quite impossible. Nonetheless there are some common elements that can be put together to create that ‘railway-like’ atmosphere and ‘prototypical’ working.

TYPICAL DAILY ROUTINES

Branch lines rarely, if ever, operated at night. Traffic levels scarcely warranted it and the expense of even the most rudimentary safety measures for running after dark would be prohibitive. That said, the start and end of the working day in mid-December would undoubtedly be somewhat nocturnal activities. As an example, we will assume that the small shed is home to two tank engines and that they are safely locked up for the night. The first arrivals will be the two shed men, who will set about the task of lighting up the engines: to give them a head start, they may have left a few small coals smouldering overnight. Both engines will be prepared, the one in front for the early morning workmen’s service to the junction, the second for the goods working that takes the full wagons and empties that had accumulated the previous afternoon.

When the crews arrive the respective firemen would join in by raising steam, gathering up the tools and doing some of the less accessible oiling up. The enginemen would come on duty at least an hour before they were due off-shed, checking the locomotives and completing the oiling, doubtless pausing for a chat over a pipe or a cigarette while they studied any traffic notices. Once steam had been raised they might well draw up to the water crane to ensure the tanks were full, with the fireman standing on the tank top to put the bag in while the engineman worked the valve. The shed men meanwhile may be topping up the bunkers from the coal dump. Eventually, and probably after a quick sluice at the shed tap and a well-earned cup of tea, the two locomotives would whistle to the signalman, if he was on duty, or set the road themselves, and then ease away to pick up their respective trains.

All that is left for the shed men to do is tidy up and complete their morning routines. To all intents and purposes the shed is now deserted: in winter there would be little need to reopen the big doors until the locomotives return at the end of their shifts.

During the day the resident engines would return periodically to replenish coal and water, with the frequency depending on the timetable, the length of the branch, loads and gradients. This offers modellers plenty of scope for licence. Other movements might include a visit by a larger engine off some special working, and the shed itself would probably have had a daily ‘full coal in and empty coal out’ and maybe even a weekly ‘empty in and full ash out’ working.

At the end of the working day the two locos would return to the shed. Their arrivals would probably be juggled to ensure the appropriate ‘first in/last out’ stabling. The first tasks would be to replenish the coal and water. Next would come the fire-dropping, clearing out the ash pan, removing any clinker from the fire-bars and finally removing the soot and ‘char’ from the smokebox. If this were done properly, there would be just enough boiler pressure remaining to roll the engine gently back into the shed. Lock the doors and that’s it. After a quick wash-down under the tap, the grubby overalls would be hung up and the crews and shed staff could cycle off to their allotments or nip across to the pub for a swift pint.

This outstanding model, based on the 100ft (30m) installation from Launceston, has graced the world-famous Dartmoor scene at Pendon Museum for many years.ANDY YORK, COURTESY PENDON MUSEUM

The ancillary facilities around the shed are highly variable. We have already discussed the need for a water tower, with or without a separate water crane. The coaling stage may be little more than a shovelling platform open to the elements or it may have some rudimentary tin (corrugated iron) shelter and a simple hoist or crane. Crew ‘accommodation’, a loose description if ever there was one, can be a purpose-built small annexe or a grounded ancient coach body. The latter is often modelled, but there are several known alternatives, such as a discarded horsebox or goods brake van, that would add interesting character to your layout.

Optional extras can include a tin-roofed shelter for drums of oil, grease and kindling wood for fire lighting. This might also be where the inevitable pedal cycles, or even the motorbikes of the younger firemen, can be stored. There may even be, if access permits, somewhere for an ancient car to be parked. Lastly toilet facilities might be little more than another tin shack round the back, or if the shed still exists in the 1960s, it might be graced by a Portaloo. External lighting would at best be sparse, but a couple of convenient posts carrying electric power or telephone cables, with lamp brackets attached, would not be out of order. That is all there might be to a single-road shed at the end of the branch line.

The other location, as a base for a banking engine, will look and work much the same. The key differences, if any, are that the locomotives would probably be larger and more powerful. Their daily comings and goings would be much more frequent and may well involve at least one crew change. The banker may also be on call around the clock, which could easily justify extra lighting and more frequent coal deliveries.

Both locations would be officially designated as sub-sheds of the nearest larger MPD. This provides the excuse for an engine change at least once a week so that the allocated loco or locos can return to the depot for boiler wash-outs and any fitting jobs that couldn’t be accomplished on site.

It is to be hoped this relatively brief description will help point modellers to their own versions of these small steam outposts. They certainly provide a wealth of opportunities that can go towards the creation of a ‘railway-like’ atmosphere together with prototypical operations, and all in a relatively small space.

MODELLING THE SINGLE-ROAD ENGINE SHED

The biggest single factor in choosing which of the many offerings one should opt for will undoubtedly be the available space. Unless the layout is intended to replicate a prototype location, the chances are that it will be a question of ‘how do I squeeze in the engine shed?’ With that in mind, and in the knowledge that the structure can always be customized or regionalized to better suit the geography, I will survey some, if not all, of the kits in ascending order of footprint or, more simply, starting with the smallest and working my way up.

BUILDING THE ALPHAGRAPHIX SHED

They don’t come any smaller than this: the main structure measures a mere 105 × 60mm. In scale terms that is 26ft long and 15ft wide (7.9 × 4.8m) and I am aware of only two of this size on the whole of the Western Region. Despite its low price of less than £5.00, it is a very complete and well thought-out kit. It includes a built-on office or storeroom, together with a water tower that can be added to the shed itself or constructed as a stand-alone item. The kit also includes two sets of double doors, enabling it to be built as a through shed, and the interior is reasonably detailed.

The package comprises just four sheets of printed A5 card. The main buildings are rather thin sheets with the stonework represented in a monochrome sepia/brown hue. These two sheets are commendably matt in finish. The two detail sheets are of a somewhat heavier gloss card and are almost full colour, being orangey-brown and black.

Alphagraphix has produced a small and inexpensive kit that is excellently designed, well printed and includes a comprehensive set of parts, but it takes some extra effort to get the best from it.

Despite its small size and low cost this is not a ‘quickie’ kit. This isn’t because it is complicated, but rather because, in my opinion, it requires some improvements and customizing to get the best from it. This particular project will take the form of a sort of combined operation in which any additional tasks are integrated with the build itself.

Options and preparations

Using a new sharp blade in your scalpel or craft knife, cut out all the main walls for the shed, the office and the water tower. Score the various marked ‘folds’, carefully using the back of your blade rather than the empty biro suggested in the instructions: with small kits like this, clean sharp folds are essential for best results. Next bend everything into shape and offer it up to your layout or proposed site plan. I used an A3 piece of foamboard marked with a 3in square grid and with a length of straight track loosely positioned as a guide.

The kit can be assembled in various configurations and a test run will help you decide which version best suits the site and the intended operations. The main building can be modelled as a through shed with normal access from either end. In this case the office will need to be attached to the side of the structure, as in the illustration on the packaging. The water tower then becomes a stand-alone item or perhaps incorporated with a coaling stage that you will need to design and build from scratch or buy an off-the-shelf version

Alternatively, the office stays at the side and the tower is built on to one or other end of the shed, so making it a single-door version but modelled with access from the left or right to suit your plans. There is a fourth configuration that is slightly less straightforward and, needless to say, that’s the one I selected. I opted to attach the office at the right-hand gable end, so the door faces outwards, and located the coaling stage and tower beside the left-hand entrance doors. This kept the whole complex within a 12 × 3in footprint, even with the extra depth needed for the coaling stage.

The walls have only a nondescript finish and it is down to the modeller to paint them or cover them with an appropriate pre-printed sheet to suit the chosen location. To illustrate this, I used watercolours to do one section in red sandstone and the other in a pale grey Purbeck stone.

At this point, whichever configuration you choose, you have two major tasks ahead. I suspect you will have already spotted that the card supplied is very flimsy and a layer of reinforcement is essential. The second decision is one of finish. The printing is acceptable, but the dull brown on sepia card is neither visually attractive nor particularly prototypical. You could cover everything in a brick or stone pre-printed paper in the time-honoured manner or you could carefully use a planked finish or even corrugated iron. This would be an appropriate occasion, however, to introduce the scratch-building technique of painting stonework over the printed sheets.

Reinforcing the walls

This is a straightforward task but it does require a modicum of care and a good sharp blade. I chose to use the card backing from an A4 pad. This is thin enough to be easy to work yet still quite thick enough to provide the required structural strength. The process is simple; each wall is laid on the card and its outline together with any doors and windows are traced out with a sharp HB pencil. In cases like this I usually draw and cut the long sides to their full size and then reduce the width of the various gable ends by 1mm each side; this enables them to fit securely between the main walls. Ultimately, as is shown on the accompanying photo, you will end up with almost two kits. When it comes to laminating them together with PVA, I recommend you fit the glazing to the main sheet shed first and then fix the reinforcing panel. This keeps the final appearance more realistic. For the office, which features bent-back stone reveals for the door and the windows, fit the reinforcing strips first so that the stonework retains the required depth. Do not go any further with the assembly at this stage.

Quick mock-ups can be used to explore the various configurations that could be assembled. It’s also a certain way to verify the need for additional reinforcing and bracing.

Painting

I chose to vary the painting of the stonework on the project example, completing one side and the end in a more reddish tone, not unlike that found around Penrith in Cumbria or on the West Somerset Railway. The other side I finished in the greyish/white stone common to many other areas in the UK. I left the office and water tower until later when I had determined the final finish.

As we have not previously discussed painting in any great detail it is worth having a look at the pros and cons. The major factor in its favour is that it gives the modeller total control over the end finish and delivers a unique appearance. The disadvantage is that it is not a quick process and takes time, practice and perseverance to get right. Personally I favour it and use it wherever possible, but that’s writing with the experience of whole villages and fully detailed farmyards behind me.

For the project I used a simple No. 2 brush for the stones themselves and a long fine-pointed ‘0’ for the shading strokes. Fortunately the kit includes a small section of printed card that is not needed for the assembly (the arched portion of the water tower base); this provided a sample on which to test the practicalities. One thing it did highlight was the un-prototypical size and brightness of the mortar courses, so the first step was to give all the walls a quick blackish wash that was little more than dirty water. Each stone was then painted individually with, on one side, a blend of reds straight from the palette, most of which were mixed with white to tone them down. The second set of sides were similarly treated, but with white slightly strengthened with some black and grey tones. The job is laborious and not made any easier by the deliberate lack of definition of the original print. For the record, each set of a side and gable end took about four hours. I like to replicate the three-dimensional effect of stonework by adding fine black shadow shading to the bottom right-hand corners of most stones. A steady hand and fine brush are prerequisites for a decent job.

The question remains, however, whether all this painting is worth the extra effort since it almost doubles the build time. My opinion is that it is more than justified as it is now very much your own work and unique to you, while also enhancing the prototypical appearance.

Assembly

Although no separate instruction sheet is provided with the kit, logic and the helpful guidance notes are more than adequate. All of the three obvious versions can now be assembled in the normal way and the only extra work is to cut out the roof bases, which are not supplied, from scrap card to the dimensions given. You may also wish to add some judiciously placed corner strengtheners to maintain the necessary square and rigid structure.

The main kit components are seen here together with their reinforcing sections, cut from the back of an A4 pad.

If you are following the option I chose, you have an extra task involving the water tower. Cut off the whole of the pre-painted back wall and simply use the reinforcing panel at this point. It is not going to be visible on the final layout and you now have a better use for those stones. Cut out two strips 15mm deep and put them to one side. These will be the supporting walls for the coaling platform. Glue the office to the right-hand gable end of the main shed. Its width will be an exact fit and this will leave the upper part of the old access doorway exposed. Offer up your remaining piece of spare stonework from the back of the tower, mark it out on the gable end, cut it to fit and stick it in place.

Once everything is solidly together, attach the roof templates to the shed and office. There are no guidelines for the finish of the roofs but I would suggest that slate is the most realistic choice. I used my usual Superquick Grey and did not attempt anything fancy.

Finally add the provided details as supplied with the kit, together with any improvements such as guttering and downpipes, and a watering facility on the tower. Basic versions can now be weathered to choice, but my design first requires us to construct a simple coaling stage.

Modelling the coaling stage

One could almost say that there were as many different versions of the coaling stage as there were sheds. Each was simply the optimum size and shape needed to fit the site and fulfil its purpose. Construction methods and materials could, and often did, reflect the style as the shed itself, but it was just as likely that recycled sleepers and basic earthworks served the same purpose.

For the project I opted to face a timber-covered earthwork with an extension of the same stone used for the shed and water tower, giving this mini-complex a more attractive and unified appearance. This is also a case where ‘size does matter’. This is a functional and working environment that may well be used several times a day. The two critical aspects are that there must be sufficient room to store and access more than a single wagonload of coal, and sufficient space for that coal to be shovelled up into the bunker of the resident tank loco. There should also be room for the barrels of lubricating oil, fuel for the pumping engine in the water tower and a heap of kindling wood for lighting up. Together that would require a minimum platform width of 60mm (15ft) and a length of not less than 100mm (25ft). A quick mock-up using a standard 10-ton coal truck and the allocated engine should demonstrate that this will work.

Your back story can contribute to the plan in that the length and frequency of service on your branch line will determine the amount of coal you will need. The average small tank engine has a bunker capacity of between 2½ and 3 tons; even if it manages to do a day’s work on one full bunker, your coaling stage will still need at least two 10-tonners each week. Increase that consumption and it’s easy to see how the shed will need a wagonload to be brought up on the morning goods every other day; and don’t forget to dispose of the ash at least once a fortnight, if not more frequently. Sometimes the coal would simply be offloaded into a heap, but a sleeper-built retaining staithe will add to the overall appearance.

For the project the stage was knocked up out of scrap card, and the staithes were formed by balsa strips to represent sleepers and by plastic tubes, cut from cotton buds, to represent recycled boiler tubes. The rest of the surface was planked using sleepers made from coffee stirrers and the platform was faced with stone using the pre-painted offcuts from the back of the water tower. A simple water supply crane was made up from a scrap of cotton bud stem, some folded masking tape and a length of model chain to control the on/off valve.

Installation

Although this is not mentioned in the instructions, the shed is designed so its stone floor rests on top of the sleepers. That means we need to use play foam to build up the surrounding areas and then site the structures on top of this. We also need to create an inspection pit somewhere in the complex. In most cases this would probably be within the shed itself, in which case it needs to be sorted before the various structures are sited. However, it is an interesting feature and all too rarely modelled, so it makes a good subject to install alongside the coal stage. In this instance the additional ash pit found at larger sheds is less necessary. With only one engine on shed, the fire would be dropped outside and the ash and clinker simply shovelled into a heap beside the track.

The final layout drawn full size onto the foamboard base. The 3in (7.5cm) grid provides a visual reminder of the space available.

Adding an inspection pit

The inspection pit should between 15 and 20ft long (60–80mm or 8 to 10 sleepers). Select exactly where it is to be sited and mark it out on the trackbed/base-board by simply ‘dotting’ between the appropriate sleepers with a ballpoint pen, and also ‘dotting’ the sleepers that need to be cut and removed.

If, as on the project, you are using a base of single or multiple foamboards then this part of the cutting process simply requires a scalpel. If you are using a single sheet, I would suggest adding one or more small sections beneath the board where the cuts will be made. This will ensure that your pit has the required depth. Seal the hole with a strip of card on the underside. If your baseboard is made from one of the wood options, then you will need to carry out some surgical carpentry. The usual method is to drill through the four corners with a large bit, perhaps adding a couple more along the sides. Connect the holes with a piercing saw and finally square them up with a heavy duty craft knife or Stanley knife and sand them smooth.