'Mon the Workers E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

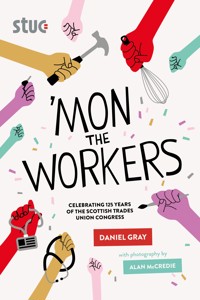

The postman and the primary teacher, the midwife and the musician. Workers in shops, workers at sea. Solidarity with the Columbian farmer and the Palestinian fireman… Modern trade unionists in Scotland perform roles in every imaginable location and are drawn from all backgrounds. They campaign to win on issues facing the colleague next to them or a comrade thousands of miles away. 'Mon the Workers tells their stories in their own words. It is a celebration of 125 years of the STUC, and a clarion call for the next generation to agitate, organise and win. This book demonstrates past achievements, explores the ideas trade unionists have fought for and rouses the movement towards future victories. 75 trade union members, reps and officials share experiences of union life from the anti-apartheid movement to Wick Wants Work. Alan McCredie's charismatic portraits of 50 other activists from the trade union movement provide a complementary visual narrative. This very human book pulses with the energy of Scotland's trade union movement, which has achieved so much and still has more to do.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 364

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DANIEL GRAY is the author of Homage to Caledonia, Stramash, Saturday 3pm and Scribbles in the Margins. He has written eight other books on football, politics, history and travel. His recent work has included screenwriting, presenting social history on television, editing Nutmeg – a Scottish football magazine – and writing across a number of national titles. He also presents the When Saturday Comes podcast.

ALAN MCCREDIE is the author of 100 Weeks of Scotland, Scotland the Dreich, Scotland the Braw and Edinburgh the Dreich. He has collaborated with authors Daniel Gray, Val McDermid and Stephen Millar on books including This Is Scotland, Snapshot, Tribes of Glasgow and Val McDermid’s Scotland. His work has appeared in national and international publications. As well as being a freelance photographer he is a lecturer in photography at Edinburgh College.

First published 2022

ISBN: 978-180425-043-3

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset by Main Point Books, Edinburgh

Text and images © Scottish Trades Union Congress, 2022

Dedicated to trade unionists past, present and future.

Contents

Foreword by Rozanne Foyer

Introduction

PART 1

VICTORIES

Justice for Surjit Singh Chhokar

Aamer Anwar

Teachers’ march for better pay

Adine Jones, Alison Beattie, Gillian Macfarlane and Leah Anderson

50/50 Campaign

Agnes Tolmie

Wick Wants Work

Allan Tait

Free school meals

Andrea Bradley

The Battle of Kenmure Street

Anonymous

Apartheid, Mandela and Scotland

Brian Filling

Freedom From Fear for shopworkers

Caroline Baird

Fast food workers rise up

Claire Peden

Opposing dockyard privatisation

Colm McConnell

Call Centre Collective

Craig Anderson

UCS work-in

David Cooper

1985 Teachers’ Strike

David Drever and May Ferries

Better Than Zero

Eilis O’Keefe

Pharmacists prescribe change

Gordon Finlayson and Paul Flynn

Stopping NHS privatisation

Grahame Smith

Responding to Piper Alpha

Jake Molloy

Defeating university pension cuts in 2018

Jeanette Findlay

Standing together for equal pay

Jennifer McCarey

Caterpillar lock-in

John Foster

Abolishing fire and rehire

John Kelly

Building a winning branch

John Neil

Time for Inclusive Education

Jordan Daly and Liam Stevenson

Menopause policy for railway workers

Kim Gibson

Bargaining for NHS workers

Lilian Macer

Keeping guards on trains

Mary Jane Herbison

Saving the Fife yards

Michael Sullivan

From Polaris to a Scottish Parliament

Pat Milligan

Saving school kitchens

Paul Arkison

Saving skilled jobs in a pandemic

Paul Leckie

Blind workers’ rights

Robert Mooney

Battle for Royal Mail

Tam Dewar

Repealing Section 2A

Tracy Gilbert

PART 2

WORKERS FOR CHANGE: PORTRAITS

A note on the photographs

Alan McCredie

PART 3

IDEAS WORTH FIGHTING FOR

Black Workers’ Committee

Anita Shelton

Resistance, unity and pensions

Cat Boyd

Fighting for older workers

Elinor McKenzie and Helen Biggins

Women’s Committee prison visit

Janet Cassidy

By artists, for artists

Janie Nicoll and Lynda Graham

Helping the firefighters of Palestine

Jim Malone

Visiting Palestine

Liz Elkind

Michael’s Story and International Workers’ Memorial Day

Louise Adamson

Another side to the miners’ strike

Margot Russell

Playing the union card

Michael Devlin

Learning on the job

Michelle Boyle

Anti-fascism, then and now

Mike Arnott

A workers’ newspaper

Ron McKay

Marching against racism

Satnam Ner

Solidarity with Chile

Sonia Leal

Union learning and growth in the taxi trade

Stevie Grant

Justice for Colombia

Susan Quinn

Solidarity visit to Bhopal

Tony Sneddon

PART 4

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES

Pardon for Miners

Alex Bennett

Safe Home campaign

Caitlin Lee

Working together for climate justice

Catrina Randall

Protecting black workers in a pandemic

Charmaine Blaize

Climate and unions at COP26

Coll McCail

Worker safety during Covid

Deborah Vaile

Unionising produce workers

Derek Mitchell

A unique LGBT+ network

Eilidh Milliken

Changing the music industry

Iona Fyfe

Making a stand with Macmerry

Keetah Konstant

Battling labour casualisation in academia

Lena Wanggren

Action on Asbestos

Phyllis Craig

Asda equal pay

Rose Theresa Skillin

Carers during Covid

Shona Thomson

From Timex to Better Than Zero

Stella Rooney

Workers in the gig economy

Xabier Villares

Acknowledgements

About the STUC

Foreword

Rozanne Foyer, STUC General Secretary

IN APRIL 2022 the STUC held our 125th Congress in Aberdeen. It was my third Congress as General Secretary, but because of coronavirus, the first where I got to see and speak in person with the reps and activists who hold our movement together.

And as we came together again after three years apart, I could not help but think back to the STUC’S Centenary Congress, held in Glasgow, in 1997. I was a young shop steward and member of the STUC’S Youth Committee. I had been invited to share a platform with the legendary Scottish miners’ union leader Mick McGahey to open the event. I was honoured. I was also terrified.

His brief was to talk about what our movement had achieved in the first 100 years of the STUC’S existence. Mine was to look towards the struggles that lay before us. I need not have been terrified. ‘We are a movement not a monument!’ said McGahey. He left the audience in no doubt that our first century had been a story both of struggle and change and that the future would be no different.

This is the central inspiration for this book.

Our movement’s history is rich with great victories and, also with glorious defeats. Perhaps though it is a story that has too often been told through the lens of our leaders, rather than those who won the victories and who suffered most through those defeats. Our more recent story has too often been stereotyped by commentators as one of inevitable decline. For those who don’t see us or who don’t want to see us, our story ended in the ’80s, crushed by Thatcher and the inevitable force of the free market.

This book says otherwise. It celebrates our past, but it is also a reflection of the sheer diversity, the optimism and the energy of our contemporary movement. It tells the story of a wide range of battles fought and still being fought. It shows how often we win. It is testament to the amazing army of workplace reps, shop stewards, health and safety reps, equality reps and learning reps who are the glue that holds our movement together.

These are the true leaders of working people.

It is they who are making change in workplaces, who are organising new groups of workers and who can take their part alongside the communities of Scotland, in fighting for change.

We are still the biggest membership-based organisation in the country. Daily we support workers to fight back against exploitation. Unionised workplaces still win better pay and conditions for workers. At a time when working people need a strong force on their side, Scotland’s trade unions have never been more relevant – or more necessary.

So, when the STUC General Council commissioned Daniel Gray to write this book, I could not have been more delighted. His concept of 75 stories and 50 images celebrating struggles past, present and future, and reaching across our movement, was perfect. How better to show that we are proud of our past but also focused on, and organising for, the future?

We could have chosen ten times the stories and pictures, and even then only scratched the surface of our diverse movement, our complex history and our hopes for the future. Nevertheless, the task of sourcing and collecting the stories and images that make up this book was a huge challenge in itself. Both Daniel Gray and Alan McCredie went above and beyond. But it was also in no small part due to the work of our 125 Project Advisory Group, to Deputy General Secretaries Dave Moxham and Linda Somerville and to Yusef Akgun, who has been working with us on the 125 project as a paid intern under the John Smith Centre Programme, and who did so much of the legwork for this project.

Then there are the story tellers themselves who have been so generous with their time, and with their memories. They have brought our movement to life. On more than one occasion reading their words brought tears of pride, joy and sadness to my eyes. They have made this not so much a book about the STUC as an institution, but a book about a whole movement. This is a story where the STUC is the common thread, running through the heart of the book that draws all these people and campaigns together in our quest to make Scotland and beyond, not just a better place to work, but also a fairer place for all workers to live.

These stories have filled me with pride and optimism. They show that it is often when things have been at their worst that we have risen best to the challenge. So many of the story tellers talk about the power of the collective and for me this is the best way, the only way, to secure a better future.

So, I hope the stories in this book will help workers draw strength and inspiration from the many victories we have won – from securing the eight-hour working day to the UCS work-in; from our support for the International Brigades fighting in Spain to our role in the anti-apartheid movement; from the anti-poll tax movement that started the downfall of Thatcher to the successful campaign for a Scottish Parliament; and on so many more occasions, organised labour in Scotland has played a key role in changing the course of history and improving working class people’s lives for the better.

Today we face huge challenges like delivering a real people-centred social and economic recovery from the coronavirus pandemic; delivering a just transition to a greener economy to tackle climate change; protecting innocent people from the horrors of war and imperialism; and taking on the cost-of-living crisis by ensuring that ordinary working people get a proper share of our country’s wealth. These challenges demonstrate that if ever there was a historic moment for our movement to act, it is now.

The current circumstances demand that working people stand up together and start fighting back. Right now, you can feel the anger building and the collective power growing once again. It won’t be easy, and we won’t win every battle ahead, that’s why the great McGahey also said ‘they don’t call it a struggle for nothing.’

But I have no doubt that through our campaigns in workplaces and communities, real progress will be made for workers in the years ahead and our greatest chapters have yet to be written. Because history shows us again and again that when we come together, our collective people power is irrepressible.

So, we will keep fighting injustices, whether new ones or those same injustices identified by those who have gone before us. I take great inspiration from our early STUC Secretary Margaret Irwin. She was a remarkable and brave woman, a Suffragist and a union organiser of women workers. She was instrumental in bringing the STUC into existence and at our first Congress in 1897, she bravely stood up in a highly male dominated environment and spoke out about the injustice of women having to do the same work for half the wages of men. It’s on her shoulders that the equal pay strikers of Glasgow stood in 2018 when 8000 of them took to the streets and won life changing sums for themselves and their families, securing over £550 million in compensation for longstanding pay discrimination from their employer, the City Council.

Like so many of the stories in this book it proves that when we let a movement build, when we educate, agitate and organise, and unite to speak with one strong voice, we are more powerful than we can dare to imagine. What at first might seem impossible, can be achieved. So, remember: the workers united will never be defeated! Long live the STUC! ’Mon the Workers!

Introduction

Daniel Gray

A BLOSSOM TREE stands sentry outside the door where Margaret Irwin, founding sister of the STUC, used to live. On this grumbling spring day, the wind puffs its loose petals through the air like berserk confetti. Their flamingo pink clashes with the whale grey ground, a peace offering to the elements. ‘Ach well,’ says a man passing by, ‘Could be worse. Could be snowing.’

Brook Street in Broughty Ferry is a long road in which pleasant homes give way to useful shops. Away from the leisure and frippery of the town’s Tayside front, it is where locals are to be found. They talk on corners and tick off errands on handwritten lists. In a thousand ways it has changed since Margaret’s time, and in a thousand ways not. Then again, the same could be said of the injustices this titan of the trade union movement railed against from the late Victorian era until her death in 1940. The jute mills of neighbouring Dundee may no longer hiss and clank, but inequalities hang now beneath different roofs, lingering in the call centre and the supermarket.

Margaret was born upon the waves of the China Seas, the daughter of a ship’s captain. Back settled on land, she attended the private Dundee High School and then Dundee University College. These were lofty beginnings compared to, say, a mill worker’s, but Margaret was never detached from the majority class around her. In fact, she had an umbilical link to their troubles, and was especially attuned to the abject conditions faced by women at work and home. She was no far-removed do-gooder, squiggling letters of disappointment to ‘Sirs’ or ‘Whomever it may concern’; she occupied the frontline, whether protesting, plotting or traipsing the tenement stairs of Dundee or Glasgow or Greenock to talk to the afflicted.

Leading roles followed. In 1891, Margaret was made full-time organiser for the Women’s Protective and Provident League, seeking to highlight the plight of female workers and encouraging them to unionise. A year later, she became Scottish Organiser of the Women’s Trade Union League, and then a Lady Assistant Commissioner with the Royal Commission on Labour. Through her diligent reporting on working conditions in shops and laundries, and of the backbreaking expectations placed on housewives, she was able to scream in eloquence through a series of written reports. Margaret also launched scorching attacks on the pay gap between men and women – again, everything changes and nothing does.

In 1895, the UK-wide Trades Union Congress (TUC) expelled Trades Councils from membership. That same, year, Margaret became Secretary of the Scottish Council for Women’s Trades, a role she would retain for the rest of her life. The trades councils she worked with saw a chance to reverse that TUC dismissal by creating something new. Throughout the following year, Margaret took part in meetings and manoeuvrings to plot what this body might be. Across 1896, she helped formulate the Scottish Trades Union Congress’s (STUC) earliest standing orders. On March 25th 1897, Margaret arrived at Berkeley Hall in Glasgow for the founding congress of the STUC.

There were 73 delegates there over that seminal three-day gathering. Margaret represented 50 per cent of the female contingent; her importance to these happenings should not disguise the fact that this remained a sphere of Macassar oil and braces. Following the short, curtailed reign of one Andrew Ballantyne, that congress elected Margaret as Secretary to the STUC’S Parliamentary Committee, forerunner to the General Council.

Her appointment did not represent the fulfilment of some vaulting personal ambition; Margaret took the job reluctantly and insisted it must only persist on an interim basis. In a telling indictment of her times, she felt having a woman and not a man at the helm ‘might be somewhat prejudicial to its [the STUC’S] interests.’ That sentiment, though, should not be interpreted as a nullifying of her ambitions for gender equality. Margaret made the cause of votes for women the cause of the STUC, driving a suffragist motion through on the conference’s final day. Women should have, said Margaret, ‘a direct voice in the making of the laws which so seriously affect them, by extending the parliamentary franchise to women on the same footing as men.’

Then as now, the STUC she helped birth would be strictly independent of the TUC, and would aim to meld the interests of workers and unions across Scotland into one bold, unified cause. Harmony and co-operation between previously quarrelsome union factions would be fostered. Pursuing that theme of change and continuity, motions in Glasgow besides Margaret’s votes for women pledge included those on Temperance and factory inspection, but also on industrial accident inquiries and tenancy law, concerns not unimaginable 125 years later when congress met in Aberdeen.

Three years on, Margaret resigned from the role of Secretary, just as she had promised. She continued to attended congresses as part of the Scottish Council for Women’s Trades delegation. Her advocacy of female workers’ causes helped create the climate in which an STUC Women’s Committee could be formed, in 1926. It remains a key component of the STUC’S work, now as then pushing for change and espousing the causes of women workers.

Until the vote was won for all women, Margaret continued her campaigning alongside her trade union work. Trade unionists were keenly aware of overlaps between issues – how, in this case, women’s political equality could harness a degree of social liberation and workplace emancipation. Not everything was harmonious, of course; Margaret herself represented the Executive Committee of the Glasgow and West Scotland Association for Women’s Suffrage in their meetings with the Women’s Social and Political Union, but then resigned in disgruntlement with their electoral strategy.

From its creation, the STUC that Margaret knew so well was there through the red-hot moments of the following decades, through unity and victory, and through discord and defeat. In her lifetime, they and their affiliate unions were a stimulating, seminal presence in the 1911 Singer Strike and the Miners’ version a year later, and the Govan rent strikes of 1915, when the government were compelled to limit the power of landlords. They were there through the tumult of George Square in 1919 and the General Strike seven years later. They – largely via trades councils – were there backing the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War through a mammoth fundraising campaign.

Margaret passed away in January of 1940. She was at home, now 61 Kersland Street, Glasgow, a handsome tenement block in autumn-red sandstone. She had played an immense, immeasurable role in improving conditions for workers, and especially women. Little wonder that, three years after her death, female employees at the Rolls Royce plant in Hillingdon, Glasgow, felt emboldened enough to strike – with war raging – for equal pay.

The STUC she had been instrumental in establishing and the movement it was part of rolled on. Together, they were influential in making happen the great societal victories of the post-war period – the NHS, the nationalisation of coal mining and other infrastructure – and in the next decade of investment in industries like the Ravenscraig steelworks in Motherwell. That formidable joint force of the STUC and its affiliates campaigned on civic issues too, pushing for equality and against nuclear weapons. An internationalism that had found its voice during the war in Spain continued, fulminating against war and oppression across the world.

Then in 1971 came the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders work-in, the oldest story to feature in the pages before you.

***

The idea of this book was not to write a history of the STUC – so brilliantly done for its 100th anniversary in Keith Aitken’s The Bairns O’ Adam – but to collate a family of stories from living memory. They are told by those who were there and are there. Where there is history, it is people’s history; individual voices reflecting on their part in wider events. Overwhelmingly, though, ’Mon the Workers seeks to look forward and to declare how yesterday’s struggles and victories can inform those of the future. It is a celebration of 125 years that fondly blows the candles of a cake and thinks about what went before, but then makes a thousand wishes and plans for the future.

Early in the summer of 2021, with the country still riven by anxiety over the horrors of Covid-19, we asked members of unions affiliated to the STUC for their stories past and present. We also encouraged them to anticipate themes and issues that future union work might encounter. There would be a focus on victories – well-known or unheralded – which stemmed from a feeling that this movement too often wallowed in glorious defeat. If we did cover those setbacks, we would do it by finding, where possible, victories within – the politicisation of women during the miners’ strike, for example.

What emerged was a vast assortment of stories as the reader will see, from saving school kitchens to ending Apartheid, and from retaining train guards to building a green future for workers. They encompassed workplace improvements, societal issues and international solidarity as befits a movement of such range and clout. Through interviews, 75 trade unionists then told these stories, so that the voices of those who mattered most were captured. Reinforcing the breadth and diversity of the movement, their words are complemented with portrait photographs by Alan McCredie of a further 50 trade unionists. Together, the 125 people featured reflect who union members were and what they were striving for in the year the STUC turned 125 years old.

’Mon the Workers demonstrates what the STUC and its affiliates do together now and will do next. The book’s stories radiate with shared aims and a collective ethos. This is a movement that strives as one – with debate and disagreements along the way, of course – to empower the 540,000 workers it represents and win for them better conditions. As a number of the accounts contained herein reflect, it is also a movement that speaks up for those who suffer discrimination at work and in wider society. The Women’s Committee that Margaret Irwin helped inspire is joined now by STUC committees for Black Workers, Disabled Workers, LGBT+ people, young people and a Pensioners’ Forum. Peppered among these personal accounts too are mentions of worker education, a vital strand of membership driven by the STUC’S Scottish Union Learning department. The continuing significance of local trades councils also glows bright. Strong too burns the flame of international solidarity movements.

What follows is not an all-encompassing, exhaustive account of everything that has happened in the recent life of trade unionism in Scotland. These are snapshots from those who wished to speak – or kindly agreed to do so – at this particular moment in time. Narratives are driven by trade unionists themselves. There are full omissions or only part-mentions that may spark gasps. Absent are: protests over Linwood, the Poll Tax and Ravenscraig; actions at Timex and Lee Jeans; Blacklisting in the construction industry; the People’s March for Jobs and the Living Wage campaign; recognition deals in the airline industry and pay wins for janitors, bus drivers or fire fighters… The list could go on, which tells its own tale of a vibrant, successful movement. Such omissions, though, were never without reason – perhaps the feeling that they had been covered extensively before, or represented that narrative of glorious failure or, quite simply, your author could not find anyone – despite best efforts – who could or would speak.

Nonetheless, the stories that follow are instructive, representative and frequently inspirational.

PART 1

Victories

TOO OFTEN HAS this movement wallowed in glorious defeat. Our songs have been of near misses and downtrodden defiance. Yet for every setback there are a hundred gains. These words proclaim some of them and the grit and guile needed to triumph. They glow with defiance and unshakeable optimism, ingrained assets in the trade unionist.

These victories are all within living memory and stretch from the workplace to the world. Some may seem small to the outsider and may have been neglected in the news cycle and previous storytelling, but to those that won them and the people that benefited afterwards, they were colossal.

The words that follow encompass democracy, protest and equality. They howl against hate and division. They are about opposing actions and detrimental changes which maim lives in work and out of it. Some are about raising the barricades when the scene suddenly changes; others are the manoeuvres of longstanding, persevering campaigns. All are about standing or sitting or marching together to protect what is right or oppose what is wrong and build something greater. Here, even the seemingly tiniest of changes embody that much.

Our stories come from the expected, bold heartlands of trade unionism – dockyards, factories, mines – but also its modern hives – supermarkets, call centres, offices. Here are the yarns of fitters, fast food workers, internationalists, cinema ushers, carpenters, lawyers, lecturers, democrats, train guards, teachers, protestors, oil workers, cleaners, postmen and women, campaigners, shipbuilders and all the rest. Each of them believed this much: if people act together, they can build a better tomorrow.

Justice for Surjit Singh Chhokar

Aamer Anwar

Lawyer Aamer grew up in Liverpool, the son of a bus driver. He moved to Glasgow in the late 1980s to attend university. In 1998, a North Lanarkshire man named Surjit Singh Chhokar was murdered in a racist attack. For the next 18 years, Aamer, Surjit’s family and the trade union movement fought tenaciously to bring his killers to justice.

MY FIRST INVOLVEMENT with trade unions was round about 1989 when I was becoming involved with student politics. Before the official St Andrew’s March was launched, we would march around that time of year and we’d be at Nelson Mandela Place and the National Front or the BNP would turn up. There were running battles. Trade unions were always present. I would see the banners.

In November 1991, I had my teeth smashed in by the police in a racist attack. When I was crying and terrified I asked them why they had done that and they said: ‘This is what happens to black boys with big mouths.’ Various left-wing groups told me to go to the Fire Brigades Union (FBU) to seek support. I went to them, they gave me a helping hand, they helped me get leaflets photocopied about the racist attack. They opened their doors to me and that was the first real involvement I had. Before they knew it me and others were printing thousands of leaflets and breaking their photocopier! That became a deep-rooted friendship that has lasted many years. They taught me the meaning of solidarity. Whenever there were demonstrations, it started off with the FBU, and then the STUC, that came hand-in-hand.

Then I became Scottish Organiser for the Anti-Nazi League. That established a link with the STUC and various other unions coming on board. There was that slogan: ‘Injury to one is injury to all.’ I immersed myself in these ideas and that slogan came to the front, because every time something happened, I was told ‘Go to the STUC, go to the FBU, they will always help you.’ I was a pain in the neck and would be constantly knocking on their doors demanding support. Then, their unconditional support would come. I would speak to the Asian community and they would say, ‘Why are they interested? They are white.’ And I could say it was because of solidarity, and that they knew an injury to one was an injury to all, and they carried that out in practice. I saw that in practice on the streets.

In 1995, the unions were still supporting me in my own case, and I became the only person of colour in Scotland to ever win a case against the police for a racist attack. In those years, I had something like five court hearings, I was arrested 25 times, I was victimised. There were times when I was to blame, on demonstrations, and there were other times when the police would literally come into the crowd and grab me. Then there’d be a riot because demonstrators knew I’d been targeted and would kick off. Since the attack, the police had always wanted me out of Glasgow.

After that verdict, I decided to go back to university and do my law degree. In 1999, a year after the murder of Surjit Singh Chhokar, I was in my final year of doing a law degree and the Stephen Lawrence case had come out. Jack Straw had stood up in parliament and said that the police was institutionally racist. That was quite a moment.

A week later, I got a phone call from some friends asking me if I had seen what had happened in the Surjit murder case. Three white men had been named as being responsible but only one had gone to court, Ronnie Coulter, and then been found guilty only of assault. That left me despondent. I felt I needed to meet with the Chhokar family.

I went to the Sikh temple at St Andrew’s Drive. I was waiting outside, I’d put a suit on to try and look smart and look like a lawyer, even though I was a final year law student. I met Manjit, Surjit’s sister, and she was not hostile but suspicious when I introduced myself and said I really need to speak to her and her family. I just wanted five minutes to say that I wanted to help. I learned from Manjit that their parents were destroyed by what had happened. It almost felt like that would be the end of it.

I phoned Bill Speirs from the STUC that day. I spoke to him and I also contacted the FBU. I said, ‘I need help.’ I spoke to Roz Foyer and Dave Moxham too, and all three at the STUC offered unconditional support. I asked the FBU for an office to run the campaign from.

I went to meet Mr and Mrs Chhokar and I told them we were going to do a press conference, and we already had a place to do that, which was the STUC headquarters on Woodlands Road. I spoke to Imran Khan, lawyer for Stephen Lawrence’s family, who has guided me a lot through my career, and he said Neville Lawrence – Stephen’s father – would come up for that. He would speak, the FBU would speak, and the STUC. Mr and Mrs Chhokar were still suspicious and I remember them saying to me, ‘Why are the STUC helping? Who are they?’ I said that they could be relied on for unconditional support and that they would mobilise in their thousands for us. Mrs Chhokar said to me, ‘How long will this take, son?’ The first mistake I made in that campaign was to say, ‘I suspect six months to a year.’ I never in my wildest imagination thought it would take just two weeks shy of 18 years for Surjit’s murder to finally get justice.

We held that press conference and all the press were there – very quickly they had called Surjit ‘Scotland’s Stephen Lawrence.’ We knew that at that time the police didn’t want to tell anyone about Surjit; they didn’t want anybody to know there had been a race attack. Within days of the murder, the family had been told that two of the guys had been released and were on the streets boasting about having killed a ‘Paki and got away with it.’ News came through also that Ronnie Coulter had got a tattoo of Devil’s Advocate on his back, which of course is a film about a lawyer who gets off guilty men.

The campaign developed huge momentum very quickly. That was March 1999, and by the summer we were having marches, demonstrations, huge public meetings. The STUC were central to that, along with the FBU, Unison, EIS, PCS, CWU and so many unions. It was very emotional. I remember many times when I’d be in tears with the family because it was a heart-breaking campaign. Mr Chhokar became seriously ill. At times the family felt they had no more tears left to shed. We just had to keep going with the campaign, fighting the criminal justice system and galvanising the campaign beyond the media and to the streets and the community. We wanted everybody to know what had happened. We realised now we were in this for the long haul.

In 1999, the family and I spoke at the May Day march. We got to Glasgow Green and I remember running into Andrew Coulter and David Montgomery, who were the other two individuals accused of the murder. They saw us and froze, and I froze. I was with Mr and Mrs Chhokar. All sorts of thoughts went through my head as I was surrounded by trade unionists. They walked very fast out of Glasgow Green.

That was the first big demonstration and rally. The support was over-whelming and moving. When we’d speak from the platform, our voices would falter and there’d be tears. My voice still falters when I think about those moments, because it was heart-breaking and it was destructive. But at every moment, the trade union movement carried us on their shoulders and gave us hope and inspiration. They kept their doors open to us. That allowed the campaign to continue through times when we faltered and argued and thought that was the end. Eventually, it felt like the whole trade union movement was on board.

In November 2000, a second trial took place at Glasgow High Court, this time for Andrew Coulter and David Montgomery. The two individuals came to court and turned around and blamed Ronnie Coulter. They said he’d boasted to his sister about killing Surjit. I remember looking round the court, and there were lots of supporters from the trade unions there wearing their orange flowers, something the judge decided was trying to interfere with the jury and they were warned. The court room was packed. The family was angry, I was angry.

In court, we’d walk across the corridor and the accused would be walking past with smiles on their faces. The family kept their dignity on every occasion. They were found not guilty and that was devastating. When the trial finished I remember holding Mr and Mrs Chhokar’s hands and we hung our heads and cried our hearts out. I felt I’d let them down. I’d promised them justice.

The St Andrew’s Day March in 2000 was a big moment in that, with thousands there and Mr and Mrs Chhokar leading. I think now it was the biggest anti-racist movement this country has ever seen. We had the support of every trade union organisation and branch, we spoke at hundreds of meetings across the country. The unions gave us the support which allowed that to happen.

We then called for a Public Inquiry. We had the whole trade union movement and every political party on our side, but we were being stitched up. They’d already carved it up and said there would be a Judicial, not Public, Inquiry, which was not what we wanted and was a slap in the face. We were suspicious and for months kept arguing against the inquiries because we knew they would be a whitewash, unless it was a public inquiry. We went to the Scottish Parliament the next day and the politicians praised the Chhokars’ dignity and all those other adjectives that are used every time a black family is subjected to this. They didn’t realise that behind closed doors, this family was full of abject rage and anger. We were heartbroken. We cried and the trade union movement cried with us.

We fought for the next six months before we boycotted the subsequent Judicial Inquiry into racism. They wouldn’t do a Public Inquiry. I remember at the time saying ‘Can you imagine having a Stephen Lawrence Inquiry where the family of the victim and their lawyers were not allowed to ask questions of witnesses, and where they were not given disclosure of evidence? And where it would be those responsible for the institutional racism practically investigating themselves?’ We walked out. The trade union movement walked out. Every black organisation refused to cooperate. We saw it as a whitewash and when it came out a year later, it was.

By then, Mr Chhokar had developed cancer, and though the trade union movement door was constantly open, we started to wind down the campaign. The family’s hearts were broken and we thought that was the end of it. After a second trial, we knew that those men could never ever be prosecuted again, and that was the end of the matter.

Years passed and we started to move on. I was a lawyer, my offices had moved out of the FBU by then! I kept on speaking at union meetings and anti-racist marches over the years. Then, fast forward a few years and the changes to the double jeopardy laws in England and Wales. Imran Khan phoned me and said, ‘This is happening and we’re going after Stephen’s killers. You need to move for that in Scotland.’ I tentatively went to the Chhokars, who by now treated me like family. Mr Chhokar was seriously ill but kept fighting back. They were both warriors.

Time had moved on, we kept up our close relationship with the STUC, and Bill Speirs had sadly passed away. We had approached the Scottish Government and they agreed to change the law on double jeopardy and then I went back to Manjit, and I explained the law had changed, and she said: ‘Let’s go for it. We need to convince my Mum and Dad.’ So we went to see them. Mr Chhokar was very, very ill by then. We were trying to convince them to give me another chance. They said no, and that they didn’t have the strength or the energy to go on more marches and to more meetings. I said they didn’t have to do anything, that we would do it. I was able to say that this time I knew people who would support this – individuals in the police who desperately wanted a result, high up legal people too, including Solicitor General Lesley Thompson QC who later because of the campaign fought became a friend to the family and myself. They eventually said yes. Mr Chhokar said, ‘You need to make me one promise, son: that you will get me justice this time.’ I thought about it, and this was the only time in my legal career I said this, I said: ‘I promise you.’ Part of me was tearing apart inside, because I knew how ill he was, and I knew if this failed it could break him. He gave me his trust, and his trust to the trade unions again.

It took two or three years, but finally the High Court said that one of the three individuals, Ronnie Coulter, could be retried because of the presence of new evidence. By 2015, sadly Mr Chhokar was severely ill. He passed away a few weeks after that decision. I was one of the coffin bearers at his funeral and gave the euology. When I looked down I could see trade union leaders, but also the Lord Advocate, Solicitor General, the Justice Minister, the Deputy Chief Constable, police escort riders. That was something you could never have considered in 1998. That respect was testimony to the perseverance and the struggle fought by Mr and Mrs Chhokar.

A year later, we went back to Glasgow High Court. Things ran like clock-work. The family was treated with respect, their supporters from the union movement were there every day with their banners outside. Trade unionists who had been there throughout were all there. There are far too many to mention, but they included the likes of Professor Phil Taylor, Roz Foyer, Simon McFarlane, Dave Moxham, Lynn Henderson, Mary Senior and so many more. The trial lasted two weeks. It felt like part of my heart was gone, by not having Mr Chhokar by my side. Ronnie Coulter sat 10 metres away in the dock. He no longer had the arrogant swagger he had once, although his lawyer, Donald Findlay QC, was still the same. This was our court. It belonged to the family. They weren’t victims now, they were warriors, and they had dragged Ronnie Coulter to court kicking and screaming 18 years after the murder. The word came through: Guilty.

We broke down. Mrs Chhokar turned around and said to me in Punjabi: ‘Finally, this man knows how as a mother I have felt, but my husband and my son will now be at peace.’ And we just hugged each other and cried.

We went back into a meeting room and hugged and smiled and cried. The young children had grown up. We pulled ourselves together and went out to the steps and made a speech. We paid tribute to the family, the Crown Office and to the police for having left no stone unturned this time. They were desperate to get justice – this was a stain on the criminal justice system in Scotland. But it wasn’t a celebration, it was a relief, and the chapter was closed.

Without the STUC and the trade unions, we couldn’t have got justice. We couldn’t have galvanised people; we didn’t have the funds and resources. We wouldn’t have had the people on the streets terrifying an institutionally racist and corrupt criminal justice system and police service. Now, when cases like this happen as has happened with Sheku Bayoh, I always say to families, ‘We’ll go to the STUC, we’ll go to the trade union movement.’

This was a textbook example of the trade union movement at its very best. Unconditional support and solidarity for a family that weren’t rich, weren’t powerful but had the stubborn love of a mother and father for a child, who refused to be silenced and patronised. And behind them, they had thousands and thousands of people from the trade union movement. They gave the Chhokars the feeling of ‘united we stand, divided we fall – we will not be defeated’. I will never forget the debt that is owed to the STUC and the trade union movement in Scotland for what they did. They gave hope, and justice.

Teachers’ march for better pay

Adine Jones, Alison Beattie, Gillian Macfarlane and Leah Anderson

Adine, Alison, Gillian and Leah are teachers at Thorntree Primary in Glasgow. Alison is the union rep and Adine, Gillian and Leah are active members in a lively union branch. After a number of internal victories on school policies, in 2018 they mobilised for the national campaign to win a 10 per cent pay rise for teachers.

Alison: When I started, I realised that there was no rep at our school. Then one day an email came from the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS) pointing this out. I asked my headteacher if I could fill the role, she said ‘yes’, and that was seven years ago.

Adine: