Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

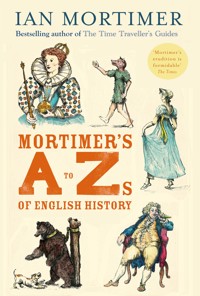

From the bestselling author of the Time Traveller's Guides In these sparkling A to Zs, time-travelling historian Ian Mortimer visits four classic periods of English history: the fourteenth century, the Elizabethan age, the Restoration and the Regency. As he ranges from the Great Plague to the Great Freeze, from Armada to Austen, and from tobacco to toenails, he shines a light into corners of history we never knew were so fascinating -- or so revealing of the whole. How did the button change life in the Middle Ages? If you found yourself at a smart Elizabethan party, should you kiss your hostess on the lips? Why were pistols safer than swords in a duel? And how come Regency Londoners quaffed so much port? This is Mortimer at his accessible and witty best. As ever, his aim is not only to bring the past to life but also to illuminate our own times.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 500

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

praise for ian mortimer

Medieval Horizons

‘A sparkling, eye-opening book’ Mail on Sunday

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England

‘After The Canterbury Tales this has to be the most entertaining book ever written about the middle ages’ Guardian

‘The endlessly inventive Ian Mortimer is the most remarkable medieval historian of our time’ The Times

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England

‘… as if Mortimer has restored an old painting, stripping it of its cloaking layers of brown varnish to reveal its vitality and life afresh’ Daily Telegraph

‘As Mortimer puts it, “sometimes the past will inspire you, sometimes it will make you weep”. What it won’t do, thanks to this enthralling book, is leave you unmoved’ Mail on Sunday

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Restoration Britain

‘If only they’d taught history like this when I was at school… Irreverent, witty and beautifully democratic, this is a delight’ i

The Time Traveller’s Guide to Regency Britain

‘This is ideal history; tales of people like us, who tell you that the past is closer than you think’ Daily Telegraph

‘Mortimer’s erudition is formidable…. The learning is lightly worn’ The Timesii

iii

iv

v

This book is dedicated to my much-loved friends, the ‘Hittites’ – Ric Horner, Dom Lawson, Elise Mori (née Alergant) and Rich Cooper – who were my companions in creativity and co-conspirators in taking everything to excess at Hitts Farm, Whimple, in 1988–90. vi

Contents

Introduction

Many years ago, when working in an archive, I picked up an old copy of Haydn’sDictionaryofDatesand came across an entry for ‘boiling to death’. Apparently Henry VIII made this the statutory punishment for poisoning after the bishop of Rochester’s cook, Richard Rose, poisoned seventeen people, two of whom died. The entry went on to say that ‘Margaret Davy, a young woman, suffered in the same manner for a similar crime, 26 March 1542.’ I was appalled. I already knew that Henry VIII was a nasty piece of work – one of the most unfeeling, selfish individuals ever to wield power in England – but that detail was more revealing of his cruelty than all the hangings and beheadings on trumped-up charges that I had ever associated with him. It spoke of his utter contempt for ordinary people and his vindictiveness, which extended to wanting to cause the maximum amount of suffering when having his subjects killed. It was no surprise to me that this law was repealed soon after his death in 1547.

That one fact taught me an important lesson about writing history. You don’t need to use lots of evidence to make a point. One single, vivid detail can be enough. Novelists sometimes employ a similar trick. If you shock people at the outset of a novel by showing your principal character coldly murdering his wife (as Henry VIII did, twice), you can create a sense that that individual is cruel beyond bounds. In the same way that ‘an image is worth a thousand 2words,’ a single startling event can reveal more about an individual than pages and pages of nuanced description.

Skip forward to 2012, when my new book, TheTimeTraveller’sGuidetoElizabethanEngland, had just been published. This was based on a very simple idea. How would England appear if you could actually visit it during the reign of Elizabethan I (1558–1603)? For example, what should you wear? Where might you stay? What might you eat? Which diseases might kill you? Which doctorsmight kill you? It seemed to me that if the past really is ‘another country’, as the writer L. P. Hartley memorably wrote in TheGo-Between, historians should be able to describe the various epochs in guidebooks in the same way travel writers do foreign countries.

The challenge I faced in promoting my TimeTraveller’sGuidewas that there was just too much information to convey to an audience. What should I include? Describing a different world – not just a single person or place but everythingin that time – takes more than an hour-long talk. Then I remembered Henry VIII boiling Richard Rose and Margaret Davy to death. If a single detail like that could be so evocative – and so shocking that it was still in my mind, twenty years later – perhaps a few well-chosen headings could illustrate the entire reign. After all, anecdotal history is one of the most memorable forms of historical writing. Just think of Alfred burning the cakes; Harold II with an arrow in his eye; Edward II’s red-hot poker; Charles II imploring ‘Let not poor Nelly starve’; and Queen Victoria being ‘not amused’. But which details should I choose to illustrate Elizabethan England? The horrors of the plague? The plays of William Shakespeare? The queen herself? What to use as loo paper? How to cut your toenails?

Those last two points might sound absurdly trivial but they too are revealing of life in different ages. It is not just the answers to these questions that are interesting: the questions themselves alert you to the fact that there are aspects to the past that you have probably never even considered. Drawing attention to such things makes you realise there are things you don’tknowyou don’t know and thatopens your mind up to all sorts of new ways of historical thinking. I therefore planned an A–Z to Elizabethan England that 3was arranged like the pieces on a chess board: small pawns of detail – which would advance steadily and show people that there are things they don’t know they don’t know – and larger themes – like castles, bishops, knights and queens – to sweep in and demonstrate the harsh and beautiful realities.

My Elizabethan A–Z talks were a success. People sometimes told me after a performance that they had been trying to guess which theme I would choose for a specific letter of the alphabet. Occasionally someone said that they had been meaning to leave by a certain time – to relieve the babysitter or catch a train – but they had simply had to hang on to find out what I would come up with when I reached X, Y and Z. There seemed to be a real enjoyment in this way of hearing about the past. I therefore developed a similar A–Z for my other Time Traveller’s Guides – to medieval England, Restoration Britain and Regency Britain.

These four talks constitute the first four-fifths of this book. Well, they do in a manner of speaking. The truth is that all four have developed hugely over the years. For a start, no two performances were ever the same, even if I tried to make them so. New ideas would occur to me each time and so the themes evolved. Moreover, in writing them down for publication, I have found myself expressing things differently – in ways that I hope are both richer and clearer than the original versions. On top of this, I have carried on learning. For example, just after I had written the Elizabethan A–Z, I was contacted by an archaeologist from Austria who prompted me to rethink everything I thought I knew about women’s underwear in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Yes, there were such things as medieval bras. This is the marvellous thing about writing a book: you send out an ambassador into the world on your behalf to make friends and contacts, and gradually, if you have done a good job, those friends and contacts get in touch with you and enrich your understanding. In some cases they have resulted in invitations to get further involved. In 2010 I was invited to join the Fabric Advisory Committee of Exeter Cathedral and so learned a great deal about that magnificent building and Decorated architecture in general. A few years later I was invited to give a keynote address on the 4development of the sense of self to an international conference of psychologists at the University of Southampton. Such events force you to re-examine what you think you know for presentation to new audiences. Hence these A–Zs have grown with me over the years.

Perhaps the most significant of these post-publication revelations was the matter of working-class life expectancy at birth compared to the life expectancy of the wealthy. It was only after finishing my Regency book, when I was thinking about how a labourer’s family could only expect to live halfas long as a prosperous middle-class family in the Regency period, that the question popped into my head: what was the equivalent proportion in earlier and later centuries? How long could a medieval peasant expect to live in comparison to a lord? And a Restoration labourer compared to the emerging bourgeoisie? Was there a progression? I did a little research and, although the results were not directly comparable, it looked very much as if the labouring classes in every other period could expect to live 85–90 per cent as long as their wealthy contemporaries. In fact, so strong was the correlation, it seemed almost a social constant. In this light, the Regency figure of 50 per cent was utterly shocking. And as you will soon discover, some parts of Regency England had a relative life expectancy that was even less than that.

Each of my Time Traveller’s Guides ends with an ‘envoi’: a short farewell from me to the reader. I have also given this book an envoi – in the form of a fifth and final A–Z. In this I attempt to sum up the experience of considering the last 700 years of English history as a series of living environments. I include things like working-class life expectancy at birth. I look back over such things as how the class system survives, why literacy is important, what it means to be English, and the concept of progress. The envoi of this book is thus, in some respects, a review of the entire TimeTraveller’sGuideproject to date. But it is not just looking back. These are also themes to carry forward. In fact, re-reading them now, it strikes me how each one is potentially the subject of a whole book. I recall Bob Dylan saying that every line of his song ‘A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall’ was the title of a song he wanted to write but, being in the middle of the Cuban missile crisis, he did not know if he’d live long 5enough to complete. The themes of this envoi are similar for me. They aren’t just what I’ve learnt from ‘living’ in the past; they are the themes that I shall continue talking about for the rest of my life, each one a book I’d write if I had world enough and time.

Here, then, are what began as my four A–Z talks, now in their richer, more developed forms, plus a shiny new, previously unheard A–Z in the envoi. I hope that the flashes from the past that follow give you some idea of your place in the great sweep of human existence. That is the main point of writing these books: they should cause us to reflect on what life is like in all ages, and thereby teach us something about ourselves. At the very least, I am sure that you will be as grateful as I am not to be a cook in Henry VIII’s kitchens.6

PART ONE

OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND

8

MEDIEVAL ENGLAND

The fourteenth century

What does the word ‘medieval’ mean to you? For many people, it will immediately trigger thoughts of the 1994 film PulpFiction, in which one of the leading characters, Marcellus Wallace, declares to a man who has just assaulted him in a most ungentlemanly manner, ‘I’m gonna get medieval on your ass.’ If this is what comes to mind, you are in good company because that term – ‘to get medieval’ – is now in the OxfordEnglishDictionary. The truth is that we generally see the Middle Ages as a time of violence and brutality. We only have to think of the crusades and the countless wars between kings, princes and warlords – of castles, walled towns, knights in armour and siege engines – to confirm our impressions. But medieval England was many other things besides violent. It was also innovative, inventive, resilient, responsible and even compassionate. I hope what follows helps you see the bigger picture. Or, rather, the deeper, richer and more interesting one.

Before we start out, however, we have to get one thing clear. What are we talking about when we refer to medieval England? When, exactly, were – or, as we will say here, when arethe Middle Ages?

The Middle Ages are generally the centuries between the fall of Ancient Rome, around AD 500, and the rise of modern times, in the sixteenth century. The term first appears in English right at the end of that period, in the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). These days historians normally place the end of the Middle Ages in the late fifteenth century or early sixteenth because of the 10many important social changes between 1450 and 1550. Printing, for example, starts in Western Europe in the 1450s, with the result that about 13 million books have been printed across the Continent by 1500. Guns become instrumental in winning battles in the early sixteenth century. There are important political watersheds at this time too: the final destruction of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) takes place in 1453. You can also see the expansion of Europe into far-distant lands as marking the end of the Middle Ages. Bartholomew Dias rounding the Cape of Good Hope and sailing into the Indian Ocean in 1487 is a significant event. So too is Columbus’s first voyage across the Atlantic five years later. But most of all, it is the Reformation – the break-up of the Catholic Church in the 1520s and 1530s – that makes the old medieval world order seem a thing of the past. As a result, the point at which historians date the end of the Middle Ages varies, depending on the context. Some put it as early as the 1450s, others as late as 1540. In some instances, there are reasons to put it even later, around 1600, when magnifying glasses and telescopes are invented and our horizons are extended towards the very small and very distant, and people generally start to learn there are things they don’t know about the world around them. Whichever date you prefer, we are talking about approximately a thousand years of history.

A thousand years is a long time by anybody’s reckoning. Life at the end of the Middle Ages has very little in common with life at the start. Therefore, if you are trying to understand everyday life in any great depth, it is wise to stick to just one century. I tend to focus on the fourteenth because it encapsulates all the things that people normally associate with the Middle Ages – castles, knights, monks and friars and, of course, the Black Death. It also allows me to define Englandin relatively simple terms. The fourteenth century is after Edward I has conquered Wales in 1272 but before Henry VIII has made Wales administratively part of the kingdom of England, in 1535. It is also long before the union with Scotland, which is a totally separate kingdom until 1603. Although it is true that the kings of England are also lords of large regions of France – over which they will continue to rule until 1453 – these form parts 11of the kingdom of France, not England, so the Channel marks a clear line of distinction.

In order to counter the impression that the fourteenth century is all bloodshed and suffering, the first handful of items I’ve chosen for my medieval A–Z offer a fairly gentle introduction to the period. And what could be more peaceful than a woolly sheep or a cow chewing its cud?

A is for Animals

Why animals? After all, a sheep is a sheep, a pig is a pig and so on. The reason is that we take some things so much for granted that we don’t imagine they have altered much over the last 700 years. Yet they have. Hugely.

Take cows, for example. Looking online to check the reports from my local livestock market in Exeter, cows these days weigh between 1,280lbs and 1,896lbs (581kg and 860kg). If you visit the same livestock market in the middle of Exeter in the year 1300, you’ll see the animals for sale are about one-third of the size of the smallestmodern cow, and less than a quarter of the size of the largest.

After you’ve taken off the horns and the hide and gutted the animal, it weighs roughly five-eighths of its alive, running-around 12weight. Dressing it to produce meat reduces its weight by a similar proportion. Thus a 1,280lb cow will produce 500lbs of beef. But the average yield from a cow in the early fourteenth century is less than 170lbs. And given the desperate need for food, there isn’t a scrap of wastage. A mature live cow in 1300 weighs about 435lbs.

It is not hard to find the reason for the change. Centuries of breeding programmes transform the medieval animals of 1300 into larger, more meat-producing beasts. This process begins in the fourteenth century. Cows are selectively bred to grow bigger so that already by 1400 they are approaching 200lbs of dressed meat, or 512lbs when running around. If you look at medieval byres, you’ll see the spaces for cows could not possibly accommodate a modern animal. The twenty-first-century record for a South Devon cow – the local breed to where I live – is over 4,400lbs. That’s ten times the size of its average medieval ancestor. That great beast couldn’t even get through the door of a fourteenth-century byre.

Much the same can be said for sheep and pigs. They too are about a third of the size of modern animals. Medieval sheep only weigh around 28lbs. Modern lambsare twice that when they go to market. Occasionally a ram in the modern world will exceed 350lbs – again, more than ten times as much as its medieval ancestors. Bear this in mind when you look at nature and think it is unchanging. The fields, animals and plants are likely to seem every bit as strange as the people.

B is for Buttons

Have you ever stopped to marvel at a button? Do you realise what a wonderful invention it is? Perhaps you don’t really think of it as an invention, it is so simple. Given this, you might be surprised to hear that although buttons were used in the ancient world, they are unknown in England in 1300. It is only in the late 1320s that a garment called a cotehardiestarts to appear at court. As a result, fashion changes forever – and much for the better. 13

To appreciate this revolution, look how ordinary people dress in 1300. A basic tunic is normally cut from two pieces of cloth, one forming the front of the chest and the front of the sleeves, and the other the back and the back of the sleeves. These are stitched together and the finished article goes on over the head. 14But having to get it over your shoulders and wriggle your arms into the sleeves means that it can’t be cut that close to the body. It hangs from your shoulders, looking like a repurposed curtain. If wealthy ladies want to have figure-hugging garments – and many do, for obvious reasons – they either have to be sewn into them or they have to have a servant lace them up at the back. And when taking off such garments, they need to be helped out of them. Unsurprisingly, most ordinary men and women normally go for something baggy, so they can squeeze their arms into the sleeves and get dressed without assistance.

Into this world come buttons. And with buttons come front-opening ‘coats’ and tunics. In the history of fashion, this is a pivotal and exciting moment. As you walk along a row of tailors’ shops on a summer’s day in London in the 1330s and see the workers sitting cross-legged on their workbenches, all the best ones are sewing a garment that will closely fit their client’s body. And these new clothes don’t just look good: the wearer can put them on quickly without the assistance of a servant. It’s a win-win. A figure-hugging look that used to take a great deal of work is suddenly effortlessly achievable. Up and down the country, provincial tailors and seamstresses see someone in the street wearing a button-fastening close-fitting tunic for the first time – when a fashionable man or woman visits town – and aim to replicate the design. By the mid-1330s, the old hanging-from-the-shoulders look is out. Now, everyone who is remotely fashion-conscious wants a tunic that will cling to his or her body as tightly as possible – because that way they can show off their muscles, hips, waists and breasts. The new look is elegant, refined and sexy. Everyone loves it – everyone, that is, except grumpy old churchmen, who remain steadfastly in their gowns and cassocks, determined to look as unsexy as possible. 15

C is for Clocks

When you think of the fourteenth century in terms of knights in their castles and monks in their monasteries, it is easy to forget that some of the most important social and technological developments affecting our lives originate in this period. One of the most important is the clock.

Just try for a moment to imagine what the world would be like if we had no clocks. You might be thinking, ‘I would not know when to turn on the TV’. But that is not the half of it. The broadcaster would not know when to put your favourite programme out. The programme itself could not have been made. In addition, the TV would not exist, nor would the means to broadcast the evening’s schedule. This is because most scientific experiments – and therefore most scientific discoveries – depend on a reliable means of measuring time. We’d have no film, no computers, no cars and no trains. Then think, when are you going to turn up for work? When might your employer expect you to turn up? When might anyone work – the government, the health service, the shops? Society as we know it would not exist without a reliable and universally accepted means of telling the time.

This is why it amuses me greatly to think of Edward III visiting Richard of Wallingford at St Albans Abbey in about 1332. On finding the good abbot building a mechanical clock – probably the first in the British Isles – the king tells him he should be doing something more useful.

Most people in the early fourteenth century still tell the time by dividing the day into twelve equal hours and the night likewise. Thus an hour of daylight is twice as long in summer as it is in winter. That’s not particularly helpful if you have a loaf in the oven. Some affluent people do have an hourglass for measuring short periods of time. But most do not.

In large towns, a specific church will take the lead in ringing the hour on its bell but the length of the hour is always down to the 16judgement of the person in charge. Churches and manor houses often have sundials. In addition, those who can use astrolabes can calculate the angle of the shadow cast by the sun from, say, a nearby tree; from this they can work out what time it is at that time of year. Some people put a stick in the ground and estimate the hour from the way the sun casts a shadow – a technique Chaucer mentions in TheCanterburyTales. But all these sundials and astrolabes require the sun to be shining. And in England, that is not always the case.

Richard of Wallingford does build his clock. And Edward III eventually sees the error of his ways. In the early 1350s the king pays for several Italian clockmakers to come to England and install mechanical clocks at Windsor Castle in Berkshire, Queenborough Castle in Kent, Westminster Palace and the royal palace at King’s Langley in Hertfordshire. Soon, cathedrals and abbeys are following his example. Salisbury Cathedral installs a mechanical clock in 1386. Wells Cathedral does the same in 1397. In 1400 countrymen can still get by with putting a stick in the ground but by then most large towns have recognised the advantages of measured time. Even Barnstaple, a relatively small town on the north Devon coast, has a clock by the end of the century. People listen out for the hour ringing out on the clock of the cathedral or nearest abbey. They talk about meeting each other at five or six ‘of the bell’ or ‘of the clock’ – just as we do.

D is for the Dead

You can’t escape the dead in the Middle Ages. They’re all around you – and not just in this country but right across Christendom. Fourteenth-century people’s vision of life extends beyond death, so that everyone who has ever lived is in one great big queue and, at death, they pass out of sight of the living in the way that people do when they cross over the brow of a hill or go round a corner. But really they are still in that queue, on their way to their final 17destination, which is Heaven. And the length of time it will take them to get there depends in part on the living.

The concept of Purgatory is fully developed by the fourteenth century. This holds that, although the saints go straight to Heaven and some terrible sinners are despatched off immediately to Hell, the majority of people’s souls are sent to Purgatory when they die. This is a sort of spiritual holding bay. They linger there in considerable discomfort until enough prayers have been said to ease their path onwards into Paradise. As a result, most wealthy families have special relationships with favoured churches where they maintain priests to pray and sing for the benefit of their souls and the souls of their ancestors. In those churches, the names of the dead are repeated every day.

It is also widely believed that close proximity to the bones of the saints – the holy dead – will bring you into direct contact with them. The saints in turn, whose souls are already in Heaven, can intercede with God to turn things to your benefit. In some people’s thinking, your dead ancestors can do something similar. If you pray for them in an appropriate fashion they can have a word with the saints, who will intercede with the Almighty. In fact, if your ancestor makes his way through Purgatory and reaches Heaven, he can put in a good word for you himself. Thus there is a whole cycle of goodwill and intercession. You pray for the dead, the dead speak to the saints, and the saints intercede with God on your behalf.

The remains of the holy dead help the living in other ways too. When swearing oaths, relics are produced, so the person taking the oath recognises the seriousness of his promises. Business dealings are often conducted in churches, close to a saint’s shrine, for a similar reason. Kings have holy bones carried into battle. Edward III’s relic collection includes bones that purportedly come from the bodies of St George, St Leonard, St John the Baptist, St James the Less, St Agnes, St Margaret, St Mary Magdalene, St Agatha, St Stephen, St Adrian, St Jerome and St Edward the Confessor. But the power of relics of saints to perform miracles is perhaps their most important function. People go on long pilgrimages – sometimes all the way to Jerusalem – to be in the presence of the remains of saints 18in the hope of being cured. Churches go to great lengths to obtain the bones of the most popular miracle-working figures in order to attract the penny-carrying crowds of sufferers desperate for a cure.

It hardly needs saying that Jesus Christ’s bones – were they to exist – would be the most treasured relics of all. Unfortunately for medieval people throughout Christendom, they are nowhere to be found. Christians believe he took them with him when he ascended to Heaven. But that does not stop them from venerating the relics that he left behind on Earth, including the shroud, the cross and the thorns from his crown. They also revere the body parts that, logically, he must have deposited here, such as his milk teeth, his sweat and his blood. And his foreskin. About a dozen churches across Europe claim to have Christ’s foreskin in their possession. Call me a sceptic but I suspect some of those claims are not genuine. One church in Rome even claims to have his umbilical cord.

E is for the Environment

What is the most earth-shattering event of the last thousand years? I always come back to two. One is the Black Death, the great plague of the fourteenth century, to which we will return in due course. The other is environmental change.

These days we all understand how environmental change can drastically affect life on Earth. Global warming would be our principal concern worldwide if it weren’t for international conflicts taking a higher priority right now (as they have done for centuries). But global warming is not simply a modern phenomenon. A slower, smaller, less-threatening form occurred naturally in the Middle Ages. Historians call it the Medieval Warm Period. It amounts to an increase in the average year-round temperature of about 1 degree centigrade worldwide between the tenth century and the thirteenth. That does not sound particularly significant. If called upon to guess the temperature right now, I would probably be out 19by at least 1 degree. But a year-round average increase, even on that modest scale, is hugely significant. A rise of just half a degree can bring forward the last frost of spring by ten days. Likewise, it pushes back the first frost of autumn by another ten days. And those extra twenty days of growth, when they are accompanied by warmer weather throughout, can see a considerable difference in harvest yields, especially at altitude. A 1-degree rise in temperature makes it far less likely you will have consecutive harvest failures above 500ft, so you can clear much more rough, uncultivated land and put it to productive uses.

As a result of the Medieval Warm Period, the population in 1290 is far higher than it has been in previous centuries. With more food to go around, more mothers can produce enough milk for a greater number of babies to live beyond infancy. That means more people reach maturity. They in turn can clear more land and create more food surpluses – and yet more babies. Almost all the potential farmland in England is being used by 1290. Not all the extra people are now needed to work on the land of the rural manors, so they start swelling the populations of the towns. More monasteries exist than ever before. More markets do too. Whereas people before the year 1000 are largely subsistence farmers working on their lords’ great estates, never handling money, by 1290 they have silver in their purses and might put it to any number of uses. It is largely due to global warming that the commercial revolution of the early Middle Ages takes place, along with most of the cultural developments we think of as medieval.

So far so good. The trouble is that 1290 is when the weather takes a turn for the worse. The Medieval Warm Period comes to a sudden stop. The Earth goes into a phase of global cooling. Frosts last longer and, in autumn, come sooner. Rainfalls are so heavy and persistent that whole summers are wiped out. In 1315 and 1316 the weather is abysmal. Animals are seen drowned in their fields. And it does not get much better over the next few years. As a result, between 1290 and 1325, approximately 600,000 people perish in England. That is 13 per cent of the population. Many families find themselves impoverished. Children with inadequate diets do not grow up 20properly but are lame or stunted. For the poor, environmental change in the early fourteenth century results in utter misery.

That is worth pausing over. It is somewhat ironic that the biggest threat the fourteenth-century world faces is global cooling – the very opposite of the environmental threat we face today.

F is for Food

Carrying on from this point about the environment, you will be shocked to see how expensive food is in the fourteenth century. To give you an idea just how much it costs, consider the standard unit of measurement known as the chicken.

In the late fourteenth century, a skilled worker such as a carpenter or a thatcher earns 4d or 4½d for every day he works. That is approximately what a chicken costs in the market. In the modern world, a free-range chicken costs about £11. No skilled worker in England today would give you a day’s work for £11. At the time of writing, the average daily wage in the UK for a carpenter or a thatcher is more than £110. Ten chickens. To appreciate how precious food is to medieval workers and their families, we need to consider our food bills being more than ten times what we pay today but our incomes being the same.

According to the Office for National Statistics, in 2023 the average UK household (with 2.4 people) spent £4,296 on groceries and £1,628 on food outside the home (restaurants and takeaways). That’s a total of £5,924 per year, or £494 per month. Imagine the average family of 2.4 people having to spend £4,940 on food every month – almost £60,000 per year. The ‘average family’ could not afford to do so. But if you’re in a family of four(as opposed to 2.4), your food shop today is likely to be considerably more than this, perhaps half as much again. To appreciate how precious food is in the Middle Ages, consider the food bill for a family of four being £90,000 per year, or £7,500 every month. Just on food. No alcohol. No rent, no heating, no clothes, no luxuries – just food.

21But that is not the end of it. Those figures relate to the latefourteenth century, after the Black Death has wiped out a large proportion of the population and wages have risen. In 1300 a thatcher earns only 2½d and a labourer only 1½d, which is less than a chicken costs at the time. Unsurprisingly, very few labourers’ families eat meat in the early fourteenth century. Most only have the chance to do so when the lord of the manor provides his tenants with a feast at Christmas or Easter. Cheese is the great saviour of the people, as it is practically the only form of protein that is both cheap and lasts through winter. Indeed, you could say that whoever discovered how to make cheese about 8,000 years ago did more for the wellbeing of humankind than any other individual in history. If you call on your early fourteenth-century English ancestors in a peasant cottage, be prepared to have a limited diet of rye or barley bread, ‘pottage’ (vegetable stews) normally made with beans, onions and peas flavoured with salt and garlic, and cheese.

G is for Guns

We don’t normally associate guns with the Middle Ages. We prefer to think of knights doing the chivalric thing and looking their enemy in the eye as they charge at them with level lances or raised battle axes. As it happens, the knights in question prefer that too. Guns aren’t very chivalric. They’re just not cricket. When Henry IV attacks the great fortress of Berwick in the summer of 1405, he first destroys the outer walls with small cannon and then takes out the Constable Tower with a single shot from one of his big guns. End of siege. Or, as we might say today, game over. Where’s the fun in that for a self-respecting knight in armour? There’s no honour in blasting people and fortifications to pieces from a safe distance.

Gunpowder was first developed in China in the ninth century. Traders bring it to Europe in the thirteenth. Guns, however, are a fourteenth-century invention. The writer Walter de Milemete includes an illustration of a small cannon in a book of princely 22advice, dedicated to Edward III, in 1326. The first recorded instance of guns actually being used in England is during the Stanhope Park campaign the following year, when the English army fires bombards against the Scots. After that, Edward III pioneers the mass production of gunpowder. By 1347 he has two tons of it stored at the Tower of London.

The irony is that Edward III is also a great champion of traditional chivalric values. He holds events in which his knights take on Arthurian roles. In the 1330s he holds tournaments almost every month in which he and his men joust with each other for glory and honour. The reason why Edward is pushing the manufacture of guns is for them to be a backup for his mass-produced bows and arrows.

At Crécy in 1346 Edward does what few medieval kings dare to do when he confronts the French army in open battle. France has a population of 20 million people – four times that of England – and is a much wealthier kingdom. But Edward has his strategy worked out. He lets the French knights attack him. He has his archers positioned on the flanks. He has his guns at the rear. As the flower of French nobility charges towards the much smaller English army, their front ranks are cut down by the English 23archers. The ranks behind the French front line lose momentum. Then they too are shot with arrows. As the subsequent waves of French knights try to reach the English army, clambering over their dead comrades, Edward opens fire with his cannon. The French knights can’t compete. The age of projectile warfare has arrived.

Guns don’t take over immediately. They are slow to load and, being very heavy, difficult to transport. They are expensive to maintain. By themselves, they do not win battles in the Middle Ages. Hence longbow archery remains the mainstay of English military superiority until the mid-fifteenth century. But guns do win sieges, as we have seen with Edward III’s grandson, Henry IV, at Berwick. Henry designs and builds his own big guns with the specific intent of demolishing castle walls. The days of besieging castles for months on end are rapidly drawing to a close, courtesy of these two English kings.

H is for Hall houses

If you are looking for somewhere to stay in the late fourteenth century, what sort of accommodation might you expect? Of course, we all think immediately of castles and manor houses, with stone walls, lofty halls and chambers with fireplaces. You might also picture four-poster beds in those chambers, chests around the room, glazed windows and a perch for your favourite hawk. But what if you are not going to stay with one of your wealthy ancestors but a more modest family who make their living from farming a few acres in the countryside?

Much depends on the region, of course. Building materials are cumbersome and heavy so it is difficult to transport them very far. Farmhouses are almost always made of local materials. On Dartmoor, in the southwest, they are normally built with stone walls. Somerset houses are often made with cob – a compound of subsoil, clay and straw. In the Midlands, you are more likely to come 24across cruck houses. These are made from trees with curved bows that are split to form a pair of cruck blades, which are then placed together to form an arch. Three or four such arches with a ridge piece joining them provide the basic structure. In the southeast, the Wealden type of timber frame becomes common at the end of the fourteenth century. This consists of an open hall with one two-storey block at one end and another similar block at the other. But wherever you go, ordinary people’s houses are always built around a main living space, called the hall.

A medieval hall has no ceiling – it is open to the roof beams. Despite this high space, it is quite dark. Windows are made secure by having vertical wooden bars to stop intruders. They do not contain glass. At night they are closed by shutters but during the day, the shutters are kept open to let in the light. People often leave the doors open during the day too, for the same reason.

A hall floor is made of packed earth and covered with straw or rushes. In the centre is the hearth, where cooking takes place on hearth stones. Smoke rises into the roof and either emanates through the thatch or a vent. Only the rich have fireplaces. The result is that the halls of ordinary houses are suffused with smoke – which swirls everywhere on account of the draughts coming in through the windows and the door, even when these are shuttered and closed. If you look up, you’ll see the beams and the underside of the thatch roof are black from years of smoke.

Near the fire you’ll see cooking apparatus, such as a tripod for suspending a cauldron over the fire, and basins and wooden vessels for holding water. People eat at a trestle table that can be dismantled when not needed. You might also see a coffer or two against the walls for storage, and benches for use at the table. But in many cases that will be all the furniture there is. Working people do not cram their houses with possessions. They do not buy things they don’t urgently need because they can’t afford to. Most of their money goes on cooking apparatus and the foodstuffs they can’t grow for themselves, especially salt. They live in an aromatic world of smoke, cooking smells and the rotting fragments of food that have fallen into the rushes in the dim light. 25

I is for Illnesses

If there is one good reason notto visit the fourteenth century, it is the health risk. We are the descendants of people who survive despite all the odds. In the pre-industrial past, injuries are common – there is no health or safety at work – and illnesses are ubiquitous. When you add the dangers of childbirth, it is amazing we are here at all. Giving birth for every woman in the Middle Ages is like playing Russian Roulette with a forty-barrel gun. It doesn’t matter how wealthy you are: there is a 2.5 per cent chance of death every time you become pregnant. If you go through childbirth a dozen times, which many medieval women do, the chances of dying in the process are more than one in four. Sadly, the baby’s chances of dying are even higher.

Perhaps the thing you’ll find most shocking is how helpless people are in the face of physical suffering. They have no idea about germ theory or the circulation of the blood. We live in an age in which we are confident we understand how our bodies work and, if there is something wrong, we know whom to ask for advice. They don’t. For most of them, their best hope is prayer or the wisdom of old women who have no formal medical training but who have nursed many sick people through their worst times.

Consider the plight of those who catch leprosy (otherwise known as Hansen’s Disease). It is caused by slow-growing bacteria that progress very slowly through the body, removing first the sensations in your hands and feet, and later paralysing your extremities, leaving them badly ulcerated. People who catch it in the Middle Ages have to ring a bell whenever anyone else comes near them. Over the years their fingers and toes melt off. That makes ringing the bell a little more difficult. But that’s not the end of their troubles. Their body hair and eyelashes fall out. Normally the bridge of the nose collapses and they are left with a smelly liquid constantly running from the gaping wound. Their teeth fall out, their penises atrophy, their eyeballs become ulcerated, their 26voices become a croak and their skin marked with large nodules. Ultimately they are left wholly deformed, stinking, repulsive and blind. Hence it is called the ‘living death’. The only good thing you can say about it is that it is becoming less common in the fourteenth century. People are dying of tuberculosis instead.

You know what’s coming next. In 1348 the Black Death reaches England – and nothing else since the last Ice Age has had such a dire effect on our population.

The Black Death is the name given to the bubonic plague outbreak of 1346–51, which affects almost all of Europe. It is spread by the bacterium, yersiniapestis, which lives in the fleas of the black rat. After a flea bites the rat and the rat has died, that flea and its friends seek another host, and given the proximity of rats and people in the fourteenth century, they may well latch on to one of us. If you are unlucky and an infected flea bites straight into a vein, you will die within a matter of hours. If you are bitten on the legs, you will find very sensitive black swellings or buboes developing in the lymph nodes in your groin. They might grow up to the size of an egg. If you are bitten on the upper body, you will feel the buboes in your armpits. Once infected, you can spread the disease to other people through your breath. After the development of the buboes, you will develop an acute fever and experience extreme headaches. If you live long enough, you will start to emit a terrible stench, vomit blood and behave as if in a drunken stupor. According to Gabriel de Mussis, a notary from Piacenza, some victims die on the day they catch the disease, some on day two, but most between the third and fifth days. You might survive – perhaps 40 per cent do – but not if you start vomiting blood.

The scale of the mortality is so great that it is difficult to comprehend. Consider it in relation to the two World Wars. World War I results in the deaths of 1.55 per cent of the UK population over a four-year period. That amounts to an annual mortality rate of just under 0.4 per cent. The Black Death kills at least 45 per cent of the English population in seven months. That is a mortality rate of 77 per cent per year. The mortality impact of the Black Death is thus roughly 200 times as intense as that of World War I. Very 27broadly speaking, 200 times as many children lose a parent. Two hundred times as many parents lose a child. As for World War II, the population of Japan in 1945 is about 70 million. To have the same impact on that country in 1945 as the Black Death has on England in 1348–49, you’d have to drop two atomic bombs like those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on two similarly large cities every day for seven months.

The Black Death is just the first wave of a pandemic that continues to kill English people for the next 300 years. It returns in 1361, 1368, 1375, 1390 and then roughly every ten to twenty years after that. Normally, the bigger the city, the greater the percentage of citizens it kills. It results in higher wages and the greater availability of luxuries, such as meat and spices, for the survivors. But it leaves their lives blighted by personal loss and family tragedy on an unimaginable scale.

As for why it is one of the two most earth-shattering events of the last thousand years (along with environment change, already mentioned in E is for Environment), it is probably ‘too soon to say’. It boosts capitalism and economic competition. It provides some families with unprecedented opportunities and thereby shakes up the entire social order. It smashes feudalism to pieces. Peasants who were effectively chained to their manors are suddenly made free. The shortage of labour means they can go where they want when they want and demand higher wages. They can marry whomsoever they want. And it changes people’s attitudes to illnesses forever. No one can continue to argue that diseases are sent by God as a blessing, so that people can atone for their sins through suffering on Earth. Babies who die in their cradles from plague have nothing to atone for. Ultimately it provokes a lot of serious questioning and soul-searching. What causes it? And what can be done to limit the damage it causes? In many ways, public health starts here. 28

J is for John Mandeville

Who is John Mandeville, you might ask? The simple answer is that he is an English traveller from St Albans in Hertfordshire. In 1322 he sets out to travel the world and, having seen all he wants to see by 1356, returns to northern France to write a book about his adventures, like Marco Polo seventy years earlier.

John Mandeville’s concept of the world is formed around its centre, Jerusalem. So his book begins with directions for prospective pilgrims thinking of setting out for the Middle East. He adds that the Holy Land is in Muslim hands because of the sins of Christians and that his readers, if they are true men of God, will reconquer the land for Christ.

With that preamble set out, John tells English people that to get to the Holy Land they must set off through Germany and travel through the kingdoms of Poland and Hungary down to Bulgaria. They must then pass into Greece or Turkey to reach the city of Constantinople. He suggests various routes through Turkey to the Holy Land. Some of these include detours that you won’t find in any modern travel book. For example, on ‘the Isle of Lango’ – wherever that is – you’ll encounter a 100ft-long dragon who was once a beautiful woman. Unfortunately, she has been changed into her current form by the goddess Diana, and she must remain like that until some brave knight kisses her on the lips.

Do dragons have lips? I don’t think so. But I love the image.

After a detailed description of Jerusalem and nearby holy places, such as Bethlehem, John tells us about Egypt, Armenia, ‘the land of Job’, ‘the country of the Amazons’ (the fighting women of ancient legends) and Ethiopia. Here, he tells you, live the Sciopods, the people with only one leg and one large foot, who can nevertheless run very fast on their one limb. When not running they shelter from the heat of the midday sun underneath their foot. Later he describes the Cynocephales(the dog-headed men and women of the Near East); the Brahmins of India; the court of the Mongol ruler, the Great Khan, 29in China; the gold-digging ants of Ceylon; and the Tibetan people who offer their dead ancestors’ bodies as feasts for the birds while eating the contents of their ancestors’ heads themselves.

That’s the simple explanation of who John Mandeville is. But who is he really?

The book is probably the work of a French monk who has never left France but who has custody of a wonderful library of travellers’ tales in his monastery. He uses bits of them to form his own travel book, pretending it’s an account of the real-life experiences of an Englishman. Whoever he was and whether he really travelled or not, all the stories in TheTravelsofJohnMandevilleare taken from other travellers’ tales. It is thus both a work of fiction and a compendium of medieval knowledge.

What is not in doubt is that the work becomes very popular after it starts to be copied in about 1357. In no time at all, it has been translated into twenty languages. And that demonstrates the important point. Just like the author, everyone in Europe is fascinated by the outside world, even if they can’t go there. What’s more, the whole idea of travel as a holy enterprise is like an electric charge to the medieval mind. Columbus is just one of the many thousands of people who will be inspired by John Mandeville. Long before his voyage across the Atlantic, people dream of making journeys into the unknown. And in the fifteenth century, the idea of converting the newly discovered parts of the world to Christianity proves an attractive alternative to the crusades.

K is for Kings

I suspect the images most frequently associated with the Middle Ages are kings, castles and battles. And it is true that the fourteenth-century kings of England fight battles and besiege castles with the same sort of regularity we hold general elections. One of the most common reasons for fighting is, in fact, a bit like a general election, in that its purpose is to determine who will run the country – 30who should be king. On 14 October 1066 Harold II loses out in the hustings of Hastings when the Norman Party under Duke William wins a clear majority. Four centuries later, on 22 August 1485, Richard III and the Yorkist Party come second in the ballot of Bosworth when Henry VII and the Tudor Party sweep the field and Richard himself loses not only his seat but also his horse and his life. Battles for the throne thus top and tail our traditional vision of medieval England.

This fact might lead you to think that nothing much changes across the Middle Ages. Despite the passing of 418 years and 312 days between Hastings and Bosworth, it is the same old story of one king bashing another over the head and taking the throne. But almost everything changes. For a start, kingship itself is turned upside down.

Before the early thirteenth century, nothing holds the king in check except a full-blown civil war; he can do whatever he wants. This explains such details as Henry I’s twenty or more illegitimate children by as many different mothers and Richard I’s reckless exploits on the Third Crusade. But in 1209 the pope puts King John on the medieval naughty step by excommunicating him. Soon afterwards, in 1215, the English barons get together and make John’s rule subject to approval by a committee when they force him to agree to Magna Carta (literally ‘the Great Charter’). John would rather die than accept such restrictions on his power – and die is exactly what he does the following year. But the principle has been established. Magna Carta gives us the theory and practice of holding kings to account.

In 1265 the first parliament to include elected representatives of the shires and boroughs is held. In 1297 Edward I acknowledges Parliament’s right to grant or withhold extraordinary taxation. Kings need taxes to be able to raise armies, so this means Parliament effectively decides whether or not England goes to war, not the king. By 1300 kings can no longer simply do what they want. If they plan to fight battles as often as Edward III, for example, they need the support of Parliament, which means the support of the leading men in the country. 31

Edward III (from his effigy). One of our greatest kings – so successful that we don’t often talk about him. We pay much more attention to those monarchs who were political failures than those who were successful.

The power of English kings shifts dramatically in the fourteenth century. Never before has an anointed king of England been deposed. After all, without Parliament, how do you depose a king? The answer is that you remove him by force – as in the case of Harold II, William II and Richard I – all of whom found themselves on the wrong end of a high-velocity pointed piece of metal. But then Edward II comes to the throne in 1307. For almost his entire reign he surrounds himself with close friends of relatively low rank who have mocked the most 32powerful earls and barons. Unsurprisingly, those earls and barons hate the king’s friends. In 1321 civil war breaks out. Edward’s opponents are defeated the following year at the battle of Boroughbridge in North Yorkshire, and he rules for a short while without opposition. Even his archenemy, Roger Mortimer (who is no connection to me, by the way), surrenders to him and is safely locked up in the Tower of London. But Roger escapes from the Tower in 1323 and, three years later, teams up with Edward II’s wife, Queen Isabella. Together they raise a small army in the Low Countries and invade England. Parliament agrees to depose Edward II in favour of his son, Edward III. Faced with the prospect of being deposed, Edward II abdicates in January 1327. He is not like his Norman ancestors; he is certainly not a king who can simply do what he wants and get away with it.

Jump forward to 1399, when another king – Edward II’s great-grandson, Richard II – is facing widespread opposition. Victory in that year’s metaphorical ‘general election’ goes to the Lancastrian Party, headed by the future Henry IV. What happens next is a reversal of the sequence of events of 1327. First Richard II is forced to abdicate and thenhe is deposed. If his abdication were the critical act marking the end of his reign, there would be no need for Parliament to depose him. But they dodepose him. What’s more they debate whether Henry of Lancaster should replace him or whether another member of the royal family should be king. Richard’s own plan is that his uncle, Edmund, duke of York, should be his successor. Parliament does not agree. When asked whether they would rather have the duke of York, the MPs all shout ‘No!’ So what about the duke’s eldest son, Edward? ‘No!’ And his other son, Richard? ‘No!’ and in that way, Parliament elects Henry IV as king.

Over the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, therefore, kings go from omnipotence to subjection to the will of Parliament. By 1400 Parliament can remove kings from power and appoint their successors. Unfortunately, this does not save us from being ruled by the cruel and vindictive Henry VIII in the sixteenth century but it is a big step in the right direction. 33

L is for Literacy

One of the biggest modern misunderstandings of the Middle Ages is the belief that only the clergy can read and write – that if you want to have something written down or need something read to you, you’ll have to find a priest. This is more or less true in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. If you are caught doing something heinous in the twelfth century but can read a chapter from the Bible, you are deemed to be a priest and can’t be hanged. However, by the fourteenth century, literacy and the priesthood no longer go hand in hand. Thousands of laymen can read and write.

As educational incentives go, you might think that notbeinghangedtakes some beating. But in the fourteenth century it is not the fear of the gallows that causes so many ordinary people to have their sons taught to read and write. It is rather the financial rewards on offer to the literate. In short, if you can read and write, more and more doors are open to you and, for a few people, great wealth awaits.