Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Phyllis Ewans, a prominent researcher in Lepidoptera and a keen walker, has died of old age. Thomas, a much younger fellow researcher of moths first met Phyllis when he was a child. He became her carer and companion, having rekindled her acquaintance in later life. Increasingly possessed by thoughts that he somehow actually is Phyllis Ewans, and unable to rid himself of the feeling that she is haunting him, Thomas must discover her secrets through her many possessions and photographs, before he is lost permanently in a labyrinth of memories long past. Steeped in dusty melancholy and analogue shadows, Mothlight is an uncanny story of grief, memory and the price of obsession.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 188

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

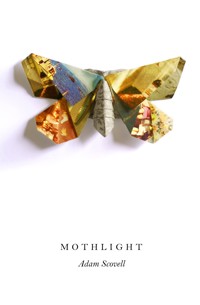

MOTHLIGHT

Adam Scovell

Influx Press London

For Nan

“…I feel as if I’m letting a ghost speak for me. Curiously, instead of playing myself, without knowing it, I let a ghost ventriloquise my words or play my role…”

— Jacques Derrida, Ghost Dance (1983)

Contents

1

To my knowledge, Phyllis Ewans had only two great preoccupations in her long life: walking and moths. An interest in these same two subjects also grew within me after a number of years of knowing her; such was the power of her influence. My predominate preoccupation today is with the study of Lepidoptera for my own academic research, and it was solely thanks to her that I followed this pathway. It dominates my life – that is, of course, when I am not plagued by my illness. Walking and moths had little to do with my early meetings with Phyllis Ewans, it must be said, and they certainly do not explain how I first came into contact with her. At that point in my childhood, Phyllis Ewans lived in the county of Cheshire, specifically The Wirral in the north-west of England. It is bordered by water: on one side the River Dee and the Welsh hills, on the other, the River Mersey and Merseyside. It was not until Phyllis Ewans moved down to London that I learned of 10her character and persona in more detail. However, being a fellow resident of Cheshire at the time, Phyllis Ewans and her sister Billie were loyal customers of my grandfather and his small business, selling them various household items regularly from his van.

On the day when I first met the sisters – a summer’s day, which made sitting in my grandfather’s van unbearable – Phyllis Ewans’ house was the last stop. I remember the terraced house in which she lived, far from the grand London house in which I would later visit her. I never understood how the money was acquired to make such a change. ‘She probably saved all the money she owed to your grandfather,’ my grandmother once said, half-jokingly, some time after the relationship between Phyllis Ewans and my own family had soured. The door of her house was green and had beautiful, stained-glass designs in the slats. The garden to the front of the house was, by comparison, ill-kept and littered with rubbish thrown by passing walkers. Phyllis Ewans, I remember, welcomed my grandfather into the thin hallway with hollow greetings. Much of the furnishing was incredibly old and a thin mist of dust and debris was always visible. I had never seen dust like it before and quietly enjoyed disturbing it with my hand to create shapes and tiny whorls in the air. The walls were covered with mounted moths and, with hindsight, I imagine this dust to be an atmosphere of scales comprised of insect wings.

Such a structure on their wings is what gives rise to the very term Lepidoptera and Phyllis Ewans’ hallway was a 11mausoleum of scales. I took little notice of her collection of moths at this point, more interested in the shelves of books, the incredibly patterned carpets and the assortment of ornaments and objects, all covered with a sheet of what looked like moth scales and dirt. I felt that I made little impression at the time, as was common when I met people. I was always a shy and inward-looking boy, as my grandmother had pointed out numerous times. But my lack of impression upon Phyllis Ewans was largely because of her sister Billie who, on the contrary, I made a swift impression upon, much to the surprise of my grandparents. Phyllis Ewans was far more discerning and could perceive at once my initial disinterest in being in their house. Billie, on the other hand, was delighted to have a young boy in their midst. She would coax me over to her chair next to the fire, and would do so many times hence. She was much older than her sister but had been a great mover in various social scenes earlier in life, as I would learn later from the many photographs I kept of her. These photos of Billie made me question the likelihood of the sisters actually being related at all, such was their difference in character and mentality. They were only sisters in name, and I still harbour daydreams surrounding the likelihood of their differing parentage.

Phyllis Ewans had time to spare in knowing me, whereas Billie’s years were numbered. She still had the air of a great and fashionable woman, brought over from her youth which was one filled with expensive fur coats, pearls, jewels and silken stockings. Imagining Phyllis Ewans’ 12undoubted scorn at such excess fills me with an amused delight now, considering the sly barbs I would encounter in my own conversations with her just applied to a more deserving victim. Having been coaxed over to the fireside, Billie reached for a small purse tucked under numerous layers of clothing and blankets. Her spindly fingers, no doubt thought of as delicate and desirable some forty years previous, wrapped themselves around a rolled-up note. She pulled my hand towards hers and, in front of the array of dead moths, placed the money in the palm of my small hand, gently wrapping my fingers around it with a ritualistic knowingness. This bought my attention on that visit, during which I all but ignored Phyllis Ewans. I was enraptured by Billie, who took great pleasure in touching the curls of my hair. As the veined and bony fingers ran their way over my head, I remember catching Phyllis Ewans watching from the doorway with a look of a disdain that I would come to recognise later in life. This had clearly been the structure of their relationship for a long time. Billie cared little for walking, and even less for moths. It is for this reason that I find her character intriguing, considering her sister was so driven by these subjects. Perhaps it was a reaction to such obsessions, yet it is clear that Billie, when not playing up for a variety of men, would occasionally try to take an interest in her sister’s passions.

I may have paid little attention to the many wonderful specimens of Lepidoptera upon the walls of Phyllis Ewans’ house on that trip but one moth enraptured me even then, and has done ever since. In fact, this point may arguably mark the earliest beginning of my own interest in moths, 13the germination of the obsession to which I thought I would devote my whole life. Perhaps Phyllis Ewans planned this, knowing the transient nature of Billie’s affections or, with even more hindsight, knowing the few years she had left to live. As my grandfather went to leave, Phyllis Ewans decided to show me a specimen she had hanging in the furthest part of the hallway. Seeing an opportunity to discuss her favourite subject, she took the mounted insect off the wall and began to tell of its history with great gusto and character, which I would not have suspected possible from the seemingly quiet and sullen woman.

The moth had stood out from the others due to its great size and its solitary mounting. The other moths, while undoubtedly beautiful, were mounted in groups of genus, family, place of capture, and sometimes even curated to the whims of the entomologist. This moth was alone, housed in a small frame on a creamy white background with the label ‘Laothoepopuli’ written in beautiful, wavy handwriting. It seemed to my young eyes even then to possess some secretive importance, some unique position ahead of all the other moths. I still have the moth, or at least the remains of it after I dropped it in shock one afternoon. With its large rounded head and grey body, even before my obsessions with Lepidoptera took hold, this moth caught my attention with ease. Phyllis Ewans could see the effect it had upon me and took pride in not needing money to buy my attention. It was a well-preserved example of a poplar hawk moth, so named due to its caterpillar’s penchant for the leaves of poplar trees. Its wings looked designed by the architect of a 14hotel from the great years of travel, with two smaller front wings that curved as if they were dripping slowly away from the thorax and down towards the abdomen. Billie did not get up to bid us farewell, though my grandfather bellowed a goodbye down the hallway, met with a feeble sound from the room. Phyllis Ewans saw us to the door, thanking my grandfather for the supplies he had dutifully brought in spite of the sisters still owing him a reasonable sum of money.

Payment was agreed for a later date and the next delivery was arranged, though I fail to remember much of the visit after seeing the moth. My mind was transfixed by the poplar hawk moth’s wings and its great size; the vision of it implanted upon my retina, speaking of strange memories which were not my own. Later in life, I walked many miles to a multitude of traps in the hope of capturing and studying such a moth, one that has become less and less common as the decades have gone by. Luckily, this was to be the first of many meetings with Phyllis Ewans as I grew up. Yet there were many complexities that arose before our friendship could develop properly, and before the great mysteries of her life would envelop my own; her own existence dissolved into the air like the scales of wings in a hallway of dead insects.

After our first meeting, I would occasionally accompany my grandfather to visit Phyllis and Billie Ewans. The latter would regularly repeat the ritual of drawing me closer 15to her fireside nest, locating the purse which lay in some unknown spot under her blankets, and crumpling heavily folded notes into my hand. I had, however, grown more interested in her sister. Beneath the walled mausoleum of mounted moths sat numerous bookcases filled with morbid books about murder. I enjoyed these volumes of detective and murder fiction, specifically for their dramatic and colourful covers. One in particular stood out, an old volume with a wasp of huge proportions bothering a much smaller plane on its cover. It was only some years later that I was disappointed to find that the novel was virtually devoid of enormously proportioned wasps. In fact, its whole plot revolved entirely around the very absence of a wasp.

Phyllis Ewans walked in on this particular visit and found her sister attempting to disrupt my own burgeoning interest in walking and moths with a collection of photos. ‘You don’t want to look at those old books. Come here and let me show you these.’ The occasions of my visits grew one summer, due to being taken care of by my grandmother. Paying a visit to Phyllis and Billie Ewans was a simple and relatively cheap way of providing entertainment for an hour or two. Soon, Billie would stop coaxing me over with her insipid fingers and cease her attempts to barter for my attention. Such was the draw of the moths and the multitude of books, even Phyllis Ewans herself would initially struggle to rouse me from my curiously quiet and obsessive studies of their possessions.

I am unfair to Billie in my memories, though I know that my feelings were shared by my grandmother, who eventually had to look after her when the woman became 16ill with age. Going through many photographs that my grandmother saved from the purge of Billie’s existence, conducted by her sister after she passed away, they showed evidence that Billie had at least attempted some compromise. In one photograph, she can be seen clearly in Phyllis Ewans’ favourite spot, in Snowdonia in North Wales, attempting to befriend a local sheep; her hand reaching out with a contradictory mixture of confidence and nervousness. On the rear of the photograph, written in Phyllis Ewans’ beautiful handwriting, is written: ‘Billie making friends with the land.’

17I began to ponder what she had meant by such a curious description: did she believe Billie to be inducted into her vision of the landscape simply through some interaction with a farm animal? Perhaps Phyllis Ewans had thought that such an action, so out of character on her sister’s part, meant an inevitable leeway in her thinking, an absolution of the resentment towards the rural climes which so often played a vital role in the loneliness of research. But the lack of similar photos shows, to my mind, that this was a rare case, one born of ‘a lack of men one weekend’, as Phyllis Ewans sharply put it one day many years later. I learned that this resentment was part of a wider divide between the sisters, and it was something that I became aware of even when visiting as a child.

It was only after Billie’s death that I would walk up to her bedroom and find her personality neatly contained within the confines of her single room in the house. The room was alien compared to the others. There were no mounted moths or moth-trapping equipment, no books, no walking sticks and very little in the way of objects that showed an interest in anything her sister cared for. A huge wooden wardrobe with mirrored panels bulged with the immense weight and volume of the clothes housed within. The air had a mist that was perceivable in the white rays of sunlight drifting through the murky net curtains. But – and I considered this even then – the mist was not fragments of wings from decaying Lepidoptera, but the disturbed remnants of powdered make-up. In many ways, they were the scales of another deceased creature. I rarely entered the room after she died, for my 18visits lessened as Phyllis Ewans prepared to move house. Before this, my visits had germinated great gaps of time in between, Billie’s dwindling life garnering a flicker-book effect, her body fading into the air around her. My interest in her waned from visit to visit but this, in hindsight, had always been dictated by seeing such a life edited through the intonations of her sister.

Despite Phyllis Ewans travelling regularly for conferences and in search of further specimens of moths around Europe, most of the documented evidence suggests that Billie did, in fact, travel more widely and more often than her sister. This may have had something to do with Phyllis Ewans’ role in several academic departments around the country, which must have curtailed her opportunities to travel far and for pleasure. Billie, in almost total contrast, worked several minor jobs in various retail roles, including numerous make-up counters in department stores. With this income and freedom, she evidently travelled with an unusual voraciousness. I found a particularly captivating picture of Billie taken in India riding an elephant. In the picture, she seems rather regal riding upon it, clearly attempting to remain composed despite the animal obviously being riled and in the middle of an undoubtedly loud roar. Neither of the sisters ever discussed the details of Billie’s trips, of course. Phyllis Ewans would never in her life engage in such an activity, never mind insist on a photograph documenting it; proudly freezing the moment in time, ready to be displayed to friends and relived infinitely. There was clearly some pride 19in the photograph at any rate, as it was kept in its own special protective holder made of a luxurious cream card, since discoloured and frayed around the edges with age.

20Perhaps Phyllis Ewans did indeed wish to travel more, especially outside of Europe which she explored in some detail in the earlier years of her life. ‘Billie may have travelled a great deal,’ Phyllis opined to me with dismissive envy on one visit, ‘but she saw very little overall, considering.’

My grandmother eventually became an unofficial carer for the older sister. Phyllis Ewans had neither the time nor the compulsion to look after her. Even when her work did not draw her out of the house and down to London on the train, she still barely acknowledged the presence of her gradually crumbling sister. It was during one of these much later visits that Billie mentioned something in passing that further ignited my interest in Phyllis Ewans, firing my curiosity. When she believed my grandparents to be busy organising food on a winter visit, she fixed a stare at her sister, who was reading a book defiantly in the adjacent wooden chair, and rasped with a strange melancholy, ‘We’re alone now and will die so but I’m sorry.’ It was as if I was not in the room, like I had faded into the strangely florid patterns of the dated wallpaper, watching this private moment between the sisters in secret. Phyllis Ewans would continually deny, even up until the day she herself died, that Billie in fact said anything of the sort during that evening. What had Billie done, I thought, that Phyllis Ewans considered so awful as to behave so coldly towards her? Even my grandmother, forever in my thoughts as my most patient relative, occasionally lost her patience with Phyllis Ewans and her coldness towards her sister. Such a detached demeanour took my naturally caring and affectionate grandmother by surprise.21

One summer’s day, I joined my grandmother on her daily visit to check up on Billie and her dying body. On entering the house, to which she had been given a key, she found Billie having spilt a hot drink, her arm partly burnt. The pain had caused her to faint and, though Phyllis Ewans denied hearing any such commotion – she was apparently working upstairs, sorting through a variety of garden tiger moths caught in a local patch of woodland – my grandmother did not for a moment believe her. I remember the vision of Billie’s slumped body and see it as the moment when she had all but died. Her funeral a week or so later was merely a triviality, despite Billie surviving for a few days after the accident. The shock of this event, and the implication that Phyllis Ewans’ detachment verged on neglect, meant that my grandmother would subsequently grow apart from her, and was incredibly surprised some years later to find my own friendship with her to be so all-encompassing and dramatically detailed.

My memories of Billie’s funeral service are aptly somewhat mixed. This is due in part to the frantic atmosphere that her death in the hospital initially caused, especially to my grandparents, both of whom were left to deal with the technicalities of the death in spite of the deceased’s sibling still being alive. The gaps in this period were later filled in by my grandmother who still harbours a great resentment towards Phyllis Ewans, even after she died. It was at this point that I made the visit to her room mentioned earlier, due, rather naively, to my grandmother insisting on fetching several changes of clothes for Billie’s stay in hospital, knowing full well that she had not long to live. One of the most surprising things 22I found in her room was a single Polaroid of Billie and Phyllis Ewans standing side by side. At that time, I had never seen a photo of the sisters together, and I was even more surprised to find that the location of the photograph was somewhere rural. Phyllis Ewans had clearly persuaded her sister to accompany her once more on a walking trip in Wales at some point in the recent past.

The house in the photo, which I paid little attention to then, would later be recognised as a key location in her shadow life. Though the ambivalence was still perceivable in the pair, it was the closest I had come to seeing them happy together; a moment long since dead. Had this moment been savoured as evidence by Billie; that she had at least attempted to make amends with her sister? It played upon my mind, reminding me that I was still in the dark regarding what exactly her sister had to make amends for. I kept the photo, worried that, once Phyllis Ewans began sorting out the room and the house, she would undoubtedly throw it away. Years later, my reasoning was proved correct when I confronted her with it. ‘I have something to show you,’ I remember saying in the large front room of her south London house. Seeing the photo, she exclaimed with some dismay, ‘Oh you should have thrown that thing away.’

23I was unsure whether she was referring to the photo or, in fact, to the very trace of the memory. Her sister had tried to meet her halfway, walking with her despite her great discomfort. I wondered how long the trip had lasted, what the pair had discussed on the long meanders up the many Snowdonian hills and mountainsides – if they had walked at all, that is. Phyllis Ewans may have wanted to discard the memory but I was determined to keep it. It sat for many years with the mounted moths that I inherited from her, the moths taking precedence in the weeks after Phyllis Ewans died, when my obsession with the women verged on an illness: the illness of Miss Ewans, as I would later take to calling it. I made sure to keep the picture propped up alongside a mounting of some garden tigers that I had cleaned up, removing the layers of dirt and dust from the glass frame.

For a brief period after Billie died, visiting the house was distinctly uncomfortable, caused by a rift that grew quickly between Phyllis Ewans and my family. She did not bother to venture to the hospital to wish any sort of goodbye to her sister, and ignored my errand to her sister’s room in search of nightwear; clothing for a ghost now venturing away from the land of its body. It could be said that she ignored what my visit to her sister’s room implied, so I thought after I had collected the items. It should have emphasised that her sister was now close to dying, but it seemed to her simply another visitation, a rattling spirit causing mild disturbances in the next room.

My grandmother and grandfather commented on the lack of empathy from Phyllis Ewans who, far from 24mourning by any publicly recognised standard, seemed almost stronger, as if a great weight had finally been lifted from her shoulders. My grandmother would often say, with a surprisingly out of character morbid humour, that she believed Phyllis Ewans had only called on the afternoon Billie had been injured because the sight of the unconscious body, sat gathering dust in the living room, had distracted from her research. ‘The bloody body was distracting her from her moths,’ my grandmother had said.