Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

'In this wonderfully eclectic collection of essays Adam Scovell makes a beguiling guide, leading us along numerous haunted byways of British and European literature, television and cinema.' – Edward Parnell, author of Ghostland 'Scovell's incisive essays, distributed across space-time, come together in this volume to form a cohesive travelogue through the hinterlands of our cultural landscape and the imaginal topographies of great artists, writers and filmmakers. It's an enriching journey that takes regular pitstops in those enchanted zones where a place and its stories are one and the same.' – Gareth E. Rees, author of Sunken Lands For more than a decade, writer and filmmaker Adam Scovell has been preoccupied by the strange connections between place and culture: curious about the graves of writers, determined to find the locations of iconic films, intrigued by the landscapes that inspired novels. From obscure British television to European cinema, the poems of playwrights to the psychogeography of Weird Fiction, Local Haunts brings together a collection of essays, photographs, travelogues, and journalism that explores the connections between art and the landscapes that inspire it. With particular focus on several key figures that emphasised place in their work – including W.G. Sebald, Alan Garner, Agnès Varda, M.R. James, and Marguerite Duras – Scovell examines culture that is haunted by locales, rural and urban. Taken from a range of print and digital publications, including work published by Sight & Sound, Literary Hub, Caught By The River, and Little White Lies, as well as Scovell's Celluloid Wicker Man site that brought many ideas surrounding Folk Horror and the Urban Wyrd to prominence in the early 2010s, Local Haunts brings together a decade of work treading the ghostways and the corpse roads of film, literature, and art.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Local Haunts

Non-Fiction 2012–24

Adam Scovell

Influx Press London

For Laura

‘There are no walls or fences. My garden’s boundaries are the horizon.’

– Derek Jarman

Contents

Introduction

I have always been drawn to strange, forgotten and uneasy places. I adore locales haunted by ghosts of the culture that I love, by synchronicities between individuals and buildings long since passed; by things ignored by most passers-by. These are what I call my local haunts.

Over the last decade or so of writing, I have not only explored and questioned ideas surrounding the links between place and culture, but have actively sought to visit and photograph places haunted by such culture; determined (though not always successful) to find potential connections between people, the artwork they have made and where they have made it.

While focusing on place as a theme in works of narrative art does have its interest, whether in novels, films, or anything else, I am in hindsight more personally interested in the maps that such idiosyncratic approaches to place chart by chance. Few exercises in creative research can have as profound an effect on the perception of a place as trudging off to find some little-known cultural marker: a location from a film, a street where a playwright lived, the grave of an author.

However, the irony present throughout is that such locality in relation to me personally is through cultural interest rather than genuine geographical connection, as odd as that may seem for people more naturally grounded in the places they’re born in. These are locales I feel I have 2inherited a connection to through the arts rather than by dint of where I was born.

Cities become film sets. Streets become libraries. Fantasy and reality blur.

Throughout the last decade, I have been lucky enough to indulge my interests, whether for my own website (when I was afforded greater freedom by money from an academic grant for a totally unconnected PhD), or for other websites that, too, have shared my interest in either culture coloured by place or places coloured by culture.

In spite of each article reprinted here having had a certain amount of rewriting, editing and new research applied since the original publication, I am still incredibly grateful to my various editors over the years who have given me the chance to carve an admittedly unusual niche for myself while never faltering in their support under the pervasive pressures of our increasingly homogenous clickbait era.

A quick glance through the contents will show that a number of key figures preoccupy me more than most. I make no apology for this, aware that several articles exploring the work of M.R. James, W.G. Sebald and Marguerite Duras may not be of interest to everyone. But I hope the potential maps provided here, through words and photographs, may encourage others to visit these unusual places and, equally, explore the unique and wonderful works they inspired.

This volume is split into three sections which naturally overlap. The opening section explores work dealing with writers. The last explores work in film and television, while the middle bridges the gap between the two, exploring both in a very literal sense. This was somewhat easier than collecting 3all the articles together that focus on the same writers and filmmakers, or ordering things chronologically. Due to the nature of a few figures, some appear across all three sections. By formatting the articles as such, it should highlight that the relationship between place and culture is a two-way street. One unavoidably informs the other, no matter the medium.

It must be said that, in collating this body of work, which represents a geographical as much as a mental map of the last ten years or so of my life, I am under no illusion that such visits or approaches guarantee any new understanding of a particular book, film or anything else. Nor do I deny that such an interest can be, at times, a lonely one. It is simply a surrendering to my curiosity, and that is all. I cannot pretend that such visits always provide insight, and I am, by my own admission, suspicious of those who do mark such connections with the confident assertion of having discovered some great alchemical secret that other writers and critics may have missed.

However, I am more than happy to approach culture from this direction, simply for my own pleasure. It is rewarding in ways that are difficult to fully explain or convey, and certainly I have found that insight does occasionally arise from such visits, some of which is hopefully present on the pages that follow.

I hope most of all that this book is of interest to those who, like me, share such curiosity in finding, exploring and celebrating culture’s own local haunts, wherever they may be.

Off the beaten track we go.

Adam 17/11/23

Literature

The Lonely Ghosts of M.R. James

I was shooting some Super-8 footage early one morning on the shingle beach of Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast when the mist started to rise. Walking the coastline in order to film a short ode to the master of the English ghost story, M.R. James, and in particular his short story ‘A Warning to the Curious’, meant ghosts were very much on my mind.

The haze slowly rose with the sun and, stood outside Sluice Cottage (the abandoned building that supposedly found its way into James’s story as the previous home of its reclusive, unforgiving spectre William Ager), the path crossed the marsh beyond with far more confidence and fortitude than I had. It was an undeniably unnerving place.

As so often happens on walks into literary works, new realisations became apparent; not simply that James had tapped into a place’s genuine eeriness to tell his macabre ghost story, but that the perspective of his stories was solitary.

Being alone in that landscape and wandering along the empty shingle beaches, as well as the marshes that seemed to exhale a strange, morbid light, showed how solitude was essential to James and his characters who, for various reasons of naivety, arrogance and greed, stumble into dangers alone, as in a nightmare. 8

Within the strange, unsettled horror of James’s ghost stories, there’s a sense of melancholy because of this solitude. The writer, a Victorian out of time and living through the dramatic changes of the Edwardian age, seems an anomaly, settling into safe havens away from the progress of modernity and his own dawning horror at its approach.

Following an almost perfect academic trajectory from Eton to Cambridge as a student, Provost at King’s College, and then finally Provost at Eton before his death, James was a writer who turned calmly away from the world around him. Such a withdrawal imbued his work with small joys: of a scholarly academic finding new curios, the pleasures of cobwebbed details. But the inevitable isolation such a life ultimately entailed was present as well.

Though James’s scholarly achievements were monumental, and still in some ways unsurpassed, he is better known for his macabre tales, which all but defined the English ghost story as an accursed form in itself. Possessed of unique antiquarian detail, James’s prose mixed a dusty sense of the ancient with an unconsciously literary sensibility, creating genuine fear and moments of distilled malevolence.

Yet underneath all of this is a perceptible sadness, the macabre hiding a more earnest loneliness. James structured his ghost stories not simply around the visceral imagery of texts and antiquity, with which he had surrounded himself for the majority of his life, but around a very real frustration: an isolated life that arguably forced the academic to make the most of more ghostly pleasures.

James first presented his haunting stories to the Chit-Chat society of King’s College, specifically when winter arrived and Christmas was close. Little could the listeners 9have known what primal horror awaited them on those early readings. Even in hindsight, the choice of reading aloud – for a society renowned for not being particularly concerned with many things bar trivialities, snuff, claret and social pleasures – still seems unusual in hindsight.

Of course, their success inspired James to eventually publish, writing stories more and more to be read rather than as a minor distraction for his peers during the Christmas period. But there’s something in this act, and in the stories themselves moving from social performance to written shorts, that conveys the true solitude of M.R. James; the man on the quiet country path, alone except for the ghosts of other concerns.

Solitude

The loneliness of James’s stories is often pervasive. Even when there is more than one person within the scenario leading to a haunting, the figure in question is usually alone or will eventually end up alone for a final ghostly retribution.

Solitude is part of the process of being haunted. Eeriness in such stories is derived from others seeing the act from afar or hearing of it second-hand via word of mouth; shrouded rather than fully present.

James’s protagonists – academics, cosmopolitans, meddlers – walk knowingly into this solitude, the company of men gradually fading from memory as if the scenario around them has become too implausible to share.

From James’s very first ghost story, ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrap Book’, it’s as if characters chase after time alone as much as the antiquarian and archaeological knowledge they 10desire. Our protagonist in this case, ‘a Cambridge man’, specifically leaves his colleagues in Toulouse to visit the churches of St. Bertrand de Comminges alone.

These friends ‘were less keen archaeologists than himself’, and he goes on ahead, such is the character’s desire to see the various historic artefacts and architecture of the town. Beneath this simple haze of minor detail lies something more telling: the Cambridge man’s mentality. He’s not merely on holiday for pleasure, but is driven by needs that even people within his field, his peers and colleagues, fail to fully understand. It’s the quiet beginning of all loneliness.

These lone men are tasked with sifting through history, pulling out the occasional object from the slipstream; objects that suggest a receding past that others, supposedly now over the horizon, are still unnervingly in consideration of. This is a task for those in solitude.

Professor Parkin of ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to you, M’Lad’ avoiding the offers of golfing games in favour of solitary walks along the coast in search of Knights Templar burial grounds; Wraxall of ‘Count Magnus’ on his lone walks past the tomb of the haunted count, desiring to see him until his hopes become horrifically realised; or Paxton in ‘A Warning to the Curious’, the amateur on the same Suffolk coastline I walked who found a cursed Saxon crown but is swept away by longings for the days when its ghostly protector didn’t provide him with constant companionship.

It’s often said that James’s characters are autobiographical, a number of traits being clearly derived from the man’s own persona: the academic nature, the fustiness, the fear of the unknown and the modern, even down to the man’s own holiday habits, often doubling up as pleasurable research 11trips to note historical interests, architecture, and sometimes the simple rapture of the landscape. But also within them is a leaning towards solitude, a recognition that, for whatever reason (often read as James’s own reality as a non-practising homosexual man in an era when such things were actively legislated against), the country path was only ever wide enough for one; choked by seclusion and the ghosts thinly veiled within it, always following.

Trauma

Trauma is embedded into the soil of James’s ghost stories. Sometimes this trauma sets in motion the narrative, but other times it is the finale coming full circle or the climax that befalls the prying protagonists. Trauma blackly manifests through this duality, as an anticipator of a violent reoccurrence and as a grammatical end to the meddling.

This trauma need not always be violent or even result in death, though it more often than not does, especially if it is anticipatory of the narrative arc and essential to the accursed nature of the land.

In ‘The Ash Tree’, a woman is burned for being a witch. The evidence of Sir Matthew Fell of Castringham – a relative of the later protagonist Sir Richard Fell – condemns the witch to certain death, though not before she curses him and the ash tee that looms outside his bedroom window. The trauma is already interred within the East Anglian land, her body later found under the tree after much demonic turmoil has unfolded. Trauma for James, it could be said, is cyclic.

Equally, in ‘Lost Hearts’, the ghosts – two children murdered by a deranged alchemist seeking their organs for 12a potion granting eternal life – are representative of a past trauma and a warning of the impending danger for the young protagonist whose heart will complete the alchemist’s bloody ritual in search of immortality.

If the trauma isn’t already embedded, then it slowly but certainly appears on the horizon for James’s solitary walkers. They sometimes walk after it in curiosity, but soon find their feet retreating on the pebbly beaches and empty country paths.

In ‘Oh, Whistle…’, this is apparent, though not necessarily violent. The character’s trauma is eventually one of a contradictory loss of faith in the rational; his views of the world around him dramatically changed by a fearful encounter with ruffling bed sheets. ‘There is really nothing more to tell, but,’ so James writes, ‘as you may imagine, the Professor’s views on certain points are less clear-cut than they used to be.’ The change is dramatic, though not necessarily always conducted down a deathly cul-de-sac.

James’s most melancholic stories, however, do end in violence, and, especially in his later writing, the trauma related to a supernatural encounter is very often deadly.

This is never more evident than in ‘A Warning to the Curious’, a story whose structure somewhat resembles ‘Oh, Whistle…’and yet features a decidedly more tragic tone. It’s impossible to shake off the feeling that, writing after the experiences of seeing many of his students and colleagues killed during the First World War, James’s more encompassing sadness is draped over his writing, darkening its hues and removing its original fireside warmth.

In ‘A Warning…’, a familiar scenario is present: a lonely wanderer searching for a lost, valuable object – the lost 13crown of Anglia – only to find it guarded by a relentless protector. Yet, unlike with Parkin, there is no moment of consideration for Paxton. His trespass, even when reversed with the crown apologetically returned to the soft soil, cannot be forgiven.

Paxton’s death is one of James’s most violent and leaves its trace on the narrator far more than others. The narrator describes in stark detail the physical wounds the poor man received: his ‘mouth was full of sand and stones, and his teeth and jaws were broken to bits’. He may as well have been the victim of a shredding round from a Vickers gun. But perhaps the most melancholy aspect of the story is detailing the sheer disappearance of the dead man. ‘Paxton was so totally without connections that all the inquiries that were subsequently made ended in a No Thoroughfare,’ writes James.

The character was so isolated, so beyond the help of anyone, that, even after the vengeful ghost of William Ager has torn his face to smithereens, the trauma pales in comparison to the wider tragedy of a man so acutely alone in the world, even in death.

Sorrow

One of the most famous fragments, oft repeated, from Robert Burton’s monumental TheAnatomyofMelancholyis also apt for James’s stories, and perhaps could even describe the author himself. ‘He that increaseth wisdom,’ wrote Burton, ‘increaseth sorrow.’ Knowledge comes with the burden of melancholy, a heightened awareness of the world and a more astute understanding of its fallacies and tragedies. 14

Intellectualism is an increasingly isolating pursuit. Even Albrecht Dürer, when sketching Melancholiain 1514, placed the character frowning and forlorn, surrounded by the apparatus of knowledge but decidedly solitary, except for an equally moribund cherub and a dog whose ribs shine through its fur to such an extent that it may actually be dead.

James’s figures fit within this model. They are often seeking knowledge through paraphernalia, relics, artefacts and objects of all kinds. Through finding cursed gold, a whistle, a child’s heart, or a Saxon crown, the lonely men believe something will be closer and within their grasp.

This knowledge is not always academic, nor is it purely satiating intellectual satisfaction. Somerton of ‘The Treasure of Abbott Thomas’ can barely hide his greed for the cursed alchemist’s gold behind a disintegrating veil of antiquarian curiosity. Again, like ‘A Warning…’, the ghost is unforgiving, the story perhaps a comment on academic arrogance, even if it was ultimately a last-minute addition for James’s first published volume. But the drive towards these things is portrayed with genuine curiosity, one that is really James’s more than anyone else’s.

It’s James who cycles alone to village churches desiring their awnings, who pores over old manuscripts, and catalogues Cambridge University’s archive of ancient texts and papers. James is the lone figure in the end, even when surrounded by peers and friends at the crackling fireside. He can’t help but seem melancholic, retreading the ghost roads of his memories in solitude, on trips where the only company in the end is the accursed and the unholy.

I was grateful for my lift arriving after hours of filming on the marshes and beaches of Aldeburgh. The feeling of 15being joined only by those unseen faded with the pale mist as a bright sun came up and brushed it aside. It never receded for James, however; he was always alone in the land. Considering the company that eventually arose to break the silence of his haunted wanderings, perhaps that is for the best.

Published by The Nightjar, 24/01/19

The Synthetic Landscape of J.G. Ballard

We’re living in J.G. Ballard’s world, so we’re often told. Such is the precision of Ballard’s not-so-futuristic predictions that it has become cliché to link our current political, technological, architectural and even social states to the man’s writing. But, outside of his great 1970s social dystopias such as High-Rise(1975) and ConcreteIsland(1974), as well as his morbid millennial retail-park nightmares of Millennium People(2003) and KingdomCome(2006), Ballard’s shorter writing has just as much to say about our time as his more famous novels.

This familiarity may be because we have moved on so little from the period of Ballard’s most popular writing, but it fails to lessen the effect of reading his work; forever inducing a look up from the page just to check that he’s not still about, somehow taking notes as the world beyond his death merges with those he created.

This feeling occurred for me most powerfully a few years back, not in front of a London high-rise or underneath a cavernous motorway as to be expected, but while visiting the ex-weapons testing facility of Orford Ness in Suffolk. Equally, it was not a novel of Ballard’s that gave rise to this feeling, but a short story written in 1964: ‘The Terminal Beach’. 17

Ballard’s story is tragic and surprisingly emotional, far from his more typical laboratory approach to character and narrative. So often does he toy with his characters’ lives that he resembles a mad scientist enjoying cruel experiments unleashed upon animals.

The story concerns a lonely man called Travern who takes refuge on the nuclear testing island of Eniwetok after the death of his wife and son. Similar to a number of Ballard’s novels, the story links the decline of the environment to the character’s mental state; the nuclear fallout from various tests suffered by the landscape decaying alongside Travern’s inner state.

Ballard psychoanalyses his character, not through some deep probing of the past, but by giving a segmented tour of the island and the carcass of its facilities; grief as damnation alley. Travern is rooting around his own cracked mind just as much as he is around the smashed, Geiger-melted concrete. He even hides from a naval search party who represent everything in humanity that he can no longer bear. Solitude in the deadly ruins is better than the companionship of the children of the atom.

‘The Terminal Beach’ is, in a way, a nuclear ghost story. It’s certainly not a naïve ‘Ban the Bomb’ tract. Travern sees visions of his deceased loved ones visiting his new edgeland territory as his mind disintegrates. They watch him from the dunes, drifting nearer as he reaches a critical mass of instability. Sitting patiently, he waits for them to speak. But there are no voices left in this world, one scarred by the continued need for nuclear weapons.

The ghosts of many atrocities haunt the text, almost cathartically like the silent screams emanating from the 18calamities barely twenty years old at the time of Ballard’s writing. Perhaps this is why, like so much of the writer’s work, ‘The Terminal Beach’ has aged so well. It’s not simply because the threat of a nuclear holocaust is still conceivable (and seems to have found an unlikely new, if oversensitive, early warning system today in the form of social media), but because there’s an anticipation to the narrative, an acceptance that the testing of such weapons unavoidably suggests their eventual use.

Apocalypse is not a theory for Travern but reality.

The island of the story was a heavy testing site for the United States, who eventually planted a huge concrete deposit there for all sorts of nuclear debris. It’s a genuine concrete island, far more disturbing than Ballard’s actual ConcreteIsland, that strange edgeland under the Westway from his 1974 novel.

My day at the National Trust terminal beach in Suffolk still stirs my thoughts with both inspiration and fear. It was a filming trip that took me on a visit to this strange coastal zone. The trip certainly reminded me of Ballard’s story.

Author Robert Macfarlane helped organise access to some of the famous laboratories on the site to film them, the same laboratories described by W.G. Sebald in TheRingsof Saturn(1996) as resembling pagodas. These are where Sebald imagined himself ‘amidst the remains of our own civilization after its extinction in some future catastrophe’.

In an essay for the Guardian, Macfarlane describes Orford Ness as ‘a dreamscape co-designed by MR James, JG Ballard and Andrei Tarkovsky’. The Ballardian element referenced here is undoubtedly a nod to ‘The Terminal Beach’, the likeness between the two places uncanny to experience, even if in differing climes. 19

The warden of Orford Ness drove us into the heart of this zone on a small electric cart straight out of a science-fiction film. The battered mesh fences, shingle pathways and marshland blurred together as my knuckles turned white from holding onto the deranged vehicle. It was, quite simply, a journey into the terminal beach, albeit one haunted by the potential of nuclear fallout rather than actual half-life hazards like Travern faces.

Ballard writes in his story that the ‘series of weapons tests had fused the sand in layers, and the pseudogeological strata condensed the brief epochs, microseconds in duration, of thermonuclear time’. There is more than a passing likeness here, even if Orford Ness was only officially the site for testing the firing mechanisms (and God knows what else). Its shifting shores feel equally scarred and difficult to measure.

Walking and filming around Orford Ness resulted in the same feeling as reading Ballard’s story: that of a temporal overlap, like receding and incoming tides briefly meeting to create a vortex. The past is there, haunting with the clanking chains of Cold War paranoia. But, if we are unlucky, so is our future.

Published by Fourth Estate, 29/11/17

Salvaging the Ashes of H.R. Wakefield

The smell of burning must have taken on a chemical flavour as the documents were piled onto the flames rippling behind the grating. In my mind’s eye, I can see a worn-down man, someone who has probably seen more of the world’s darkness than he realistically would have liked, stoking the fire. Piles of ephemera are littered at his feet: letters yellow with age; typed and handwritten manuscripts telling bizarre tales of the uncanny; even some photographs of the man himself.

He was trying to disappear.

In one sense, it was a burning of his mere identity: an action that suggests, more than anything else, a desire to become a ghost before his time. The vanishing man was Herbert Russell Wakefield, a writer of ghost stories. Judging by the lack of discussion of his work today, he almost succeeded in his task. As with everything in our age of digital eternal return, however, disappearance is only the first step towards reappearance.

Unsurprisingly, considering the denomination of his name, Wakefield wrote a combination of ghost stories and weird fiction. Christian names are a curse to weird fiction writers. Like H.P. Lovecraft, M.R. James and E.F. Benson, 21Wakefield wrote short tales of the supernatural, slotted into the everyday lives of his distinctly Edwardian era.

Though writing with similar emphasis on personal terror as the writers he followed – James, Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, et al – his writing soon slipped from the public consciousness, falling rapidly out of print and only reprinted a handful of times after the Second World War. Even a collected volume in the 1970s, when a taste for such stories was rife once more, failed to garner the sort of attention given to reprints of similar writers and their work. Wakefield is notable by his consistent absence, as if his ritualistic burning cursed future attempts to bring him back from the grave.

He was born in Sandgate, Kent, the third child of his clergyman father Henry Wakefield, the eventual Bishop of Birmingham. He went to boarding school in Wiltshire – Marlborough College, to be exact – before, like many Old Marlburians, entering Oxbridge to study History at Oxford’s oldest institution, University College. Following in the footsteps of Percy Shelley and C.S. Lewis did little for him, as he spent more time on sports, passing through the college with only a reasonable grade and future expectations.

He took his first steps into publishing soon after graduating, working as secretary to the mogul-esque press baron Alfred Harmsworth, before the First World War brought that career to a halt. Serving in the Royal Scot Fusiliers, he saw action in a number of battles and soon rose to the rank of captain. Certainly, reading the stories he would soon produce, war regularly rears its head as the cause of the disturbed state of his protagonists.

The other pillar of his characters’ lives was an equally brutal endeavour: working in the publishing industry. 22After a stint in America, coupled with a failed marriage, he found a home in London and worked his way up the ranks at William Collins, eventually becoming a chief editor. His characters are frequently intertwined with publishing and, even more so, in the writing of ghost stories. Because of this, his stories sometimes lapse into something akin to ghostly auto-fiction, spiced up with biting critiques of his industry’s smarminess.

By the late 1920s, he’d started work on his ghost stories, publishing TheyReturnatEvening:aBookofGhostStoriesin 1928. He would go on to publish several volumes and become a regular name in anthology editions and magazines of weird fiction, producing a vaguely respected body of work that would soon fall into shadow. By the end, he seemed jaded with it all. ‘I’ve written my last ghost story,’ he wrote in the introduction to his final volume, StrayersfromSheol(1961). ‘I believe ghost story writing to be a dying art.’

So what lay behind Wakefield’s stories? Where did they share likenesses and differences with his contemporaries? And will his spirit be summoned again from the groaning shelves of dusty libraries, or should he be left to rest with the ashes in his fireplace as he so clearly desired?

Shadows

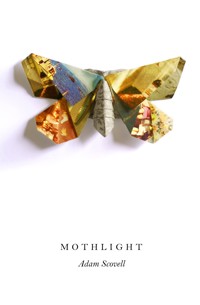

In an apt crossover between reality and fiction, my one and only volume of Wakefield’s stories was gifted to me via a partly fictional character. The fictionally malevolent but assuredly real and incredibly friendly nonagenarian Phyllis Ewans (who inhabited my first novel, Mothlight(2019)) left her collection of macabre books to me after she died. 23

Among them was one dusty volume of Wakefield’s stories; an original 1932 edition of GhostStoriesprinted as part of Jonathan Cape’s Florin Series that boasts being ‘the right size for all times, and the right price for these times’. That price was 2snet each. In this series, Wakefield shared space with the likes of Flaubert, Hemingway and the Brontës. In his lifetime, at least, his status was assured.

Reading Wakefield in the context of the writers he openly admired can be a strange experience, like coming upon misremembered echoes and even retellings of other works. In many ways, his stories (at least those I’ve managed to find) fill a gap between the fusty, antiquarian world of M.R. James and the weirder, post-Pinter world of Robert Aickman, all horn-rimmed spectacles and PlayforToday. Wakefield is a sort of missing link between the two, with one overriding concern that partly accounts for the eventual disappearance of his work: the insufferable social milieu of his characters.

The ordinariness of his stories is double-edged, explaining both their strengths and weaknesses. If P.G. Wodehouse had considered more ghastly matters than the wrong tie or an accidental engagement, perhaps his stories might have resembled Wakefield’s to some degree.

A sense of class hierarchy is present from the first tale that opens GhostStories, ‘Messrs. Turkes and Talbot’. Like many of his protagonists, Bob Fanning is the Oxford-educated son of rich parents who decides, almost on a whim, to go into publishing, where he ‘spends most of his time yawning over typed garbage’. Some things never really change.

Though Wakefield’s characters are not especially malicious, it’s hard to feel any sympathy for their experiences. 24At times, the violent, unforgiving spirits found in James’s work are much missed. In ‘Old Grey Beard’, one of Wakefield’s stranger and more daringly erotic stories, even the image of a sultry, caressing grey beard haunting the dreams of a young woman, April Mariella, cannot distract from her intolerable social surroundings. Ghosts and demons appear a welcome distraction.

The troubled story of April ends in peaceful contemplation and contentment with her marriage to the ‘bland and innocent’ Mr Peter Raines, who, having recently left Oxford (again), is about to publish a ‘slim volume of essays’ entitled ConstructiveToryism. On reading this, I briefly missed the presence of William Ager, the ghost with a decidedly more unforgiving disposition from James’s ‘A Warning to the Curious’ (1925).

Another common occurrence to examine before visiting the more attractive elements of Wakefield’s work is his obsession with detailed golfing scenarios. In a number of stories, golfing technique and ability are used to gauge the character for the reader rather than actual characterisation. It’s almost impossible to get away from this world; one that is reminiscent, perhaps ironically, of the psychotic narrator in Patrick Hamilton’s HangoverSquare(1941). In a Wakefieldian setting, golfing prowess would have been enough to secure social standing in the circle of Earl’s Court fascist acquaintances of Hamilton’s George Harvey Bone.

In ‘The Red Hand’, Wakefield’s writerly protagonist considers making one of his own characters left wing because ‘Magazine readers hate “Reds” worse than murderers – there were more of ’em.’ Couple this with the protagonist of ‘Mr Ash’s Studio’ – who, having written 2540,000 words, declares, regarding people he disagrees with, ‘as golfers say I “don’t want them back”’ – this gives us a sense of Wakefield’s world, and his lack of insight in contrast to writers such as Hamilton. The latter understood that the banality of the hateful human elements manifesting in Europe then also enjoyed a few occasional rounds on the fairway.

Putting aside golf, the real haunting in these stories isn’t the implied spirit or malevolent creature but often the valets, golf caddies and servants drifting at the edges, seeming little more than a nuisance. It’s a dated precedent, but one worth opening the discussion of Wakefield’s work with, simply to show his period twinge and blind spots. For, from these everyday elements, there arises a more interesting thing: Wakefield’s modernity.

Modern Spirits

In trying to summarise Wakefield’s stories, the best template I could find was in their likeness to the darker films of Ealing Studios, notably its chief portmanteau horror DeadofNight(1945). With an array of short segments of varying quality, they all explore that same Edwardian world, from club performers to tweed-wearing upper-middle-class cads in cottages. If that film’s own particular golfing segment, featuring the equally Wakefieldian Charters and Caldecott, represents the lesser aspect of his work, then its incredibly effective final story – involving a cursed ventriloquist’s doll – captures the atmosphere of Wakefield’s stronger work.

There’s little doubt that, despite some passing resemblances to M.R. James’s stories, Wakefield’s are more 26defiantly modern. His world has little in common with the fusty, hallowed realms of James’s scholarly dons, with Lovecraft’s ancient evils or Machen’s excavated eeriness. Wakefield is even postmodern in regard to his relationship with James specifically, referencing his stories overtly several times, including in ‘Nurse’s Story’, which has the following exchange between a young child and a nurse:

‘And you read too many of those ghost books. That James, he gives me the creeps!’

‘Oh, I love them, Nurse; especially, “Oh whistle and I’ll come to you!”’

In a number of stories, Wakefield’s strangeness manifests in more than simply postmodern quotation, but uniquely in the presence of that most dreaded of elements for James: sex.

As James wrote in one introduction to a volume of ghost stories, he found writers who brought sex into ghost stories frustrating. ‘They drag in sex, too,’ he wrote, ‘which is a fatal mistake; sex is tiresome enough in novels; in a ghost story, or as the backbone of a ghost story, I have no patience with it.’ This may also explain why James was so cautious in praising Wakefield’s work.

In the same introduction, James suggested of Wakefield and his volume TheyReturnatEveningthat the author ‘gives us a mixed bag, from which I would remove one or two that leave a nasty taste. Among the residue are some very admirable pieces.’ It’s impossible not to understand what James is really talking about here, slipping into the same tactile language that Wakefield’s more affair-filled, quietly seductive stories use. We know what that residue is. 27

In ‘Mr Ash’s Studio’, the narrative is overtly sleazy. A writer – of ghost stories, of course – rents a studio in which is housed the painting of a woman regularly covered in bizarre red moths that attack on sight. It turns out later that Mr Ash, the partying artist and previous owner of the studio, was eventually betrayed by the woman in the portrait, who married another man in Surrey. Scandal is suggested as far worse a manifestation than demonic insects.

Equally, many stories have some undercurrent of sexuality; affairs are rife and middle-class, tense and simmering like in David Lean’s BriefEncounter(1945). Women are sometimes presented as the femmesfatalesof noir novels: glamorous but deadly, proportioned to the male gaze but ultimately to its downfall. Wakefield’s modern acceptance of melodramatic sexuality adds an edge to his stories absent in the work of many of his peers.

Ordinary Dread

Wakefield was not confined to this urbane and modern form of horror. He also ventured into more typical old worlds that other writers of his stripe inhabited. In ‘The First Sheath’ (1940), the strangeness resides in the almost clichéd, tradition-ridden English village where, as one of the story’s narrators suggests, ‘there are maypoles, of all indecorous symbols, and beating the bounds, a particularly interesting survival with, originally, a dual function; first they beat the bounds to scare the devils out, and then they beat the small boys that their tears might propitiate the Rain Goddess.’

It’s almost the norm for this form of weird fiction to, at some point, paint villages as housing secrets, cults and 28violence; so much so that Wakefield’s stories in this vein, while accomplished, are hardly essential or new.

It’s Wakefield’s unusual, modern domesticity that frames his originality best. ‘The Cairn’, for example, follows a pair of interlopers looking to climb a semi-fictionalised escarpment in the Lake District. Despite the locals warning against climbing it when snowy – due in part to some unnamed and suspect creature reminiscent of Maupassant’s Horla – an unfortunate climb does take place.

Rather than getting straight to the action or taking time on place and setting (a common feature of the form), Wakefield spends more time sketching the character of the naïve climbers.

The leading man, Pat Seebright, ‘made an easy £10,000 a year in his father’s stock-broker’s firm’. His life is laid out for the reader in all its tedious detail, yet the effect is wonderful. Pat’s climbing partner is less successful but, interestingly, Wakefield implies an amorous relationship between them, expressed in part by having the pair fall in love with the same woman as a substitute.

The modern lives of these city slickers are not merely an excuse for their naivety, but often take up the sort of detailed space usually reserved for malicious history, ancient folklore and local superstition. Wakefield finds the modern everyday just as interesting and as suffused with curious detail.

In many of the stories, he doesn’t even contend with such rural settings, reaffirming his horror with what could be called urban folklore, or what I’ve previously termed the urban wyrd.

In ‘Used Car’, an old American car turns out to be imported from Chicago, and is the final resting place of 29several gangsters and a double-crossing floozy. The upper-class family of buyers and their driver begin to replay history, lapsing through time slips into the final moments of murder, feeling as if they’re being choked.

Outside of self-published ‘real’ ghost story volumes, and E. Nesbit’s ‘The Violet Car’, the closest thing I’ve come across to this outlandish but effective story is in hearsay regarding the missing Nigel Kneale-penned episode of the BBC science-fiction anthology series OutoftheUnknown. TheChopper(1971), as Kneale called it, was equally haunted, and an unfortunate Patrick Troughton contended with the spirits of the bike’s previous rider. That, however, was in the early 1970s, when such modern quirks had fully established themselves; commonplace items of day-to-day life then normalised enough to be deployed in stranger fictions.

Wakefield wrote ‘Used Car’ in the early 1930s, before cars were so dominant in public life. It shows, to my eye at least, that he had a unique understanding of stranger day-to-day aspects, and how new technology had the potential to slip into the weird and the terrifying. There are few writers of the post-war years who, because of this, do not owe Wakefield in some way for his Victorian – even Dickensian – capacity for being terrified of (and questioning) the cursed machinery that popped up in the twentieth century.

Salvaging the Ashes

So, what to make of Wakefield’s legacy? Though for a time mentioned alongside the writers he admired, and even suggested as being a potential successor to their enjoyable 30evils, his stories are in far lower standing today. Even writers specialising in exhuming these types of forgotten figures have referred negatively to his work for its seeming mediocrity, often unfairly so. Perhaps there’s a uniquely eccentric character to his stories that does not translate well for modern readers.

Wakefield’s characters are often artists or writers, and the way they are characterised evokes images of Bloomsbury sets and earlier pre-war bohemia. In his noted classic ‘The Red Lodge’, an artist takes his family away to help with his work, only to succumb to strange visions and hauntings. The creative process is painful for Wakefield and for his characters. The sheer number of stories involving the publishing industry and struggling writers is too long to list. Yet this is when Wakefield is at his most biting and witty.

In another story, ‘The Red Hand’, we follow a writer in first person as he returns to the draft of an incomplete ghost story. The way the fable is constructed means it’s almost a dramatisation of a real-time edit, far more experimental in quality than other ghost stories of the period. It’s only when the dreaded red hand of his narrative finally breaks from his page onto ours that the oddness of the story becomes truly apparent.

Wakefield can’t help but allow his criticism of the industry to come through in the story, reminding us, after all, that he was the man who burned as much evidence as possible of his own writing life. Of course, some does still exist, including the occasional photograph. But it appears he was pretty successful in his destructive endeavour. ‘He had a conscience. In his dirty little way he was an artist. But 31never would he write again…’ as he suggested in ‘The Red Hand’. His honesty and accidental autobiography are almost too sharp to bear.

Reading my old volume of GhostStoriesaround October, I once again pictured the face in Wakefield’s photographs burning behind the grate of a fireplace. Sometimes it’s best to honour the wishes of writers and accept their desire for disappearance.

In Wakefield’s case, however, I instinctively stretch out a hand in reflex towards the fire, and grab a clump of those still-warm, smouldering ashes; hoping to maybe conjure in a circle of words the standing of a lost, sometimes flawed, but ultimately innovative writer of pleasing terrors.

Published by The Nightjar, 27/12/20

Alan Garner’s Remembered Landscapes

Throughout his career, Alan Garner has dedicated many books to questioning the landscape of his native Alderley Edge in Cheshire. Under the guise of the fantastical, at the heart of all Garner’s work lies a sense of place dictating the direction of his stories. Alderley is not a mere narrative device so much as an expression of personal experience. Garner not only still lives in the location, but is continually haunted by it.

More than most British writers, Garner has livedthe places of his books. It’s a rare feature in the age of extended travel and a hyper-globalised populace. He has spent most of his life in and around Alderley, predominantly in Congleton under the shadow of the Lovell Telescope of Jodrell Bank. It’s a place imbued with strange tales and folklore; where the cosmic and the archaic intertwine with ease.

In particular, Garner has been fixated on the Edge that gives Alderley its name: a stone precipice with sweeping views out over the Cheshire plains, all the way to Manchester when the skies are clear (looking like a Mordorian realm from afar, sitting obtusely on the green plain). From his debut novel TheWeirdstoneofBrisingamen(1960) to his memoir, WhereShallWeRunTo?(2018), place is fixed, not simply to set the scene or to provide a backdrop, but because it defines everythingin Garner’s work. 33

Garner’s prose is carved from rock and wood, giving the impression that it has always been here, and the feeling that he is continuing the tradition of his craftsman heritage. Considering a memoir by Garner is in itself an intriguing proposition, if only because his work has often been drenched in biography and the place that coloured it. Was one really necessary when the man’s history is there in between the wizards and time-shifts of his fiction?

On a wall near the house of his birth, his forefather’s name is cut into the stone, a signature of a modest masonry achievement and a call from those once there to future ancestors. Garner’s prose is the same modest signature etched from the elements; of the land remembered and of the remembering land.

Remembering the Land

Especially in his fiction, Garner places land on par with character. In his novel TheOwlService(1967), for example, the majority of the book is taken up either with dialogue or place description; there’s very little in between. A good example is this simple but beautiful passage: ‘Alison sat in the shade of the Stone of Gronw among the meadowsweet. Clive stood in the river.’ This binary allows for a melding of inner and outer worlds, meaning the reader can see quite plainly how place slowly becomes pivotal to the lives of the characters. Rarely do they fail to mention or imply some aspect of their location: the roads, paths, hills, forests, peaks and fields that surround them make up a fair amount of their discussion.

They remember the land even when they wish to forget it. 34

Susan and Colin of the Weirdstonetrilogy walk the same paths that Garner walked with his father; around the Edge itself, up to Stormy Point and past the various wells that litter the area. One in particular stands out: the ‘Wizard’s Well’ that’s rumoured to be a product of Garner’s great-great-grandfather, its carved wizard face specifically. It’s the same wizard who would eventually turn up as Cadellin Silverbrow in TheWeirdstoneofBrisingamen.

As Garner wrote in that book:

Just as they were about to turn for home after a climb from the foot of the Edge, the children came upon a stone trough into which water was dripping from an overhanging cliff, and high in the rock was carved the face of a bearded man…

The passage could easily be from WhereShallWeRunTo? with its detail gleaned from memory.

It’s fitting that a similar narrative of wandering with his father found its way into his memoir. If anything is remembered from Garner’s past, it’s almost always enshrined by place. Even when his emotions are the overriding element being summoned, as in his novel Red Shift(1973), they are almost always remembered through (and preserved by) place like an insect in amber.

The Land Remembering

In an essay from TheVoiceThatThunders, Garner writes of the Edge that it ‘both stopped, and melted time’. In his fiction and essay writing, the landscapes of Cheshire, Wales 35and Alderley have potential sentience. If his characters at any point forget the importance of the place around them, then it will do its utmost to remind them.

Alison of TheOwlServiceand her frustration at being stuck on holiday in the Mawddwy Valley is a good example of this, as is Ian in Thursbitch(2004), who is reluctant to leave the ailing Sal to the mercy of the temporally permeable Pennines.

Ever since RedShift, temporal shifts have dominated Garner’s landscapes, often hinting towards a kind of agency. The three male characters of RedShift, Ian and Sal of Thursbitch, and even William Buckley of Strandloper(1996) all partake in some unspoken communion with the terrain around them, as if the past filters in and allows access to some deeper truth.

Reading Garner’s non-fiction, this is clearly reflective of his own relationship with the land. However, to label the latter as an expression of psychology undermines what is really happening, as it seems so essential to all of his post-RedShiftnarratives, perhaps even being their key instigator. This is even when, as in these later novels, the elements of place-painting are reduced to an absolute minimum.

Psychology seeks answers. Garner’s writing, on the other hand, is pure expression, intuition even.

Place instead haunts through names and language, sometimes so intensely localised, unfamiliar and idiosyncratic to the north-west of England that they seem possessed of incantation as much as geography.

This emphasis on locality feels like a form of remembering, an interaction beyond exploration and normal language. It tells of a dangerous openness to place if unaware or dark of heart. 36

In another essay, Garner wrote of the Edge that:

It is physically and emotionally dangerous. No one born to the Edge questions that, and we showed it proper respect.

This respect is not superstitious or even melodramatic. It’s simply an acknowledgement of a heightened awareness of place in temporal terms; one that is part of a shared continuity with generations gone by.

The past is not fixed underneath the rock and soil but constantly drifting back and forth as the land remembers, even when we briefly forget.

Published by Fourth Estate, 10/08/18

The Haunted Realms of The Owl Service

I can’t remember exactly when I first read Alan Garner’s The OwlService(1967). Like its inspiration, TheMabinogion, or the Stone of Gronw that sits at the centre of its mystery, it seems to have always been there.

It’s an unusual feeling because the novel is not particularly old by standards of literature – it turns fifty on the 21st August 2017 – and yet it feelsolder. It may carry the trappings of a very particular analogue period of the twentieth century – with its 35mm cameras in particular playing a vital role – but Garner’s connection to deep, unfolding history allows TheOwlServiceto function very much like a more antiquarian text.

This is, however, in contrary to the actual writing, which is deeply modern in form, experimenting with voice and perspective in ways that still seem daring today. This short novel, award-winning in the arena of children’s fiction at least, feels unearthed from the ground and yet constructed through accumulated retellings by modernists at the fireside, every evening’s version adding layers of crumbly mystery.

Garner began writing TheOwlServiceafter a number of coincidences. The first was being given a dinner service patterned with an owl-and-flower motif; the flowing design 38effectively portrays owls made of flowers, or perhaps flowers made of owls. The plate was designed by Christopher Dresser, and typically fed into the Cheshire writer’s propensity for drawing on his everyday life and surroundings, even when writing and considering narratives of fantasy.

The second coincidence was a trip that Garner took to Bryn Hall in Dinas Mawddwy. The reality of place always takes precedence in Garner’s work. The house and surrounding valley seemed a perfect landscape in which to begin a continuation of TheMabinogion; the twelfth and thirteenth-century collection of Welsh tales divided into branches of legend, myth and adventure. TheOwlService is in itself an archaeology of the branch that concerns Math, son of Mathonwy, telling of a love triangle and the jeopardy that comes from a betrayal.

Garner’s narrative follows Alison and her new stepbrother Roger, who are taken to the Welsh valleys by their recently wedded parents, to their holiday cottage which resides deep in the countryside. The house is maintained by a groundskeeper called Huw, a housekeeper called Nancy, and her young son, Gwyn.

When Alison hears a scratching noise in the roof above her bedroom, Gwyn goes to investigate and finds a dinner service covered with a strange design, part owl, part flower. Alison begins to make cut-outs of the flowers, making them into owls before the designs disappear.

Eerie events unfold as the tale of Blodeuwedd from The Mabinogion