13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

The tragic story of how Rudyard Kipling sent his son to his death in the First World War. The year is 1913 and war with Germany is imminent. Rudyard Kipling's determination to send his severely short-sighted son to war triggers a bitter family conflict which leaves Britain's renowned patriot devastated by the warring of his own greatest passions: his love for children - above all his own - and his devotion to King and Country. David Haig's play My Boy Jack was first staged at Hampstead Theatre in 1997. It was revived at the Theatre Royal, Nottingham, in 2004, and toured the UK. The play was filmed for television in 2007, with Daniel Radcliffe as Jack and the author himself as Kipling.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

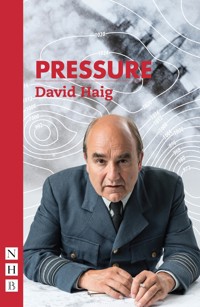

David Haig

MY BOY JACK

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Original Production

Characters

Act One

Act Two

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

My Boy Jack premiered at Hampstead Theatre, London, on 13 October 1997. First preview was 9 October. The cast was as follows:

RUDYARD KIPLING

David Haig

CARRIE KIPLING

Belinda Lang

JOHN (‘Jack’) KIPLING

John Light

ELSIE (‘Bird’) KIPLING

Sarah Howe

GUARDSMAN BOWE

Billy Carter

GUARDSMAN DOYLE, COL. RORY POTTLE, MR. FRANKLAND

Fred Ridgeway

GUARDSMAN McHUGH, MAJOR SPARKS

Dermot Kerrigan

Director

John Dove

Designer

Michael Taylor

My Boy Jack was made into a television film and first broadcast on ITV on Remembrance Day, 11 November 2007. It premiered in the United States of America on PBS on 20 April 2008. The cast included:

RUDYARD KIPLING

David Haig

CARRIE KIPLING

Kim Cattrall

JOHN (‘Jack’) KIPLING

Daniel Radcliffe

ELSIE (‘Bird’) KIPLING

Carey Mulligan

Director

Brian Kirk

Screenplay

David Haig

Characters

RUDYARD KIPLING

Mid-forties, wiry, energetic, walrus moustache, huge eyebrows, balding, spectacles

CARRIE KIPLING

Rudyard’s wife. Mid-forties, short, handsome, somewhat formidable

JOHN (‘JACK’) KIPLING

Rudyard’s son. Sixteen years old at the beginning of the play. Tall, gangly, and extremely short-sighted

ELSIE (‘BIRD’) KIPLING

John’s older sister. Eighteen years old at the beginning of the play. Intelligent, forthright, inquisitive

GUARDSMAN BOWE

GUARDSMAN McHUGH

GUARDSMAN DOYLE

Members of John’s platoon of Irish Guards

MR. FRANKLAND

A friend of Guardsman Bowe

MAJOR SPARKS

An Army Doctor

COL. RORY POTTLE

Representative of the Army Medical Board

The play requires a cast of seven actors

ACT ONE

Scene One

September 1913.

Drawing room. ‘Batemans.’ RUDYARD KIPLING’s home in Sussex. In the room is a book case, a long table, and an oak cabinet, above which hangs a large oil portrait of a six-year-old girl.

RUDYARD is alone. He is opening a parcel. In it are the scores of several Music Hall songs.

RUDYARD. Oh, good.

He places the music on the table, and gleefully lights a cigarette. He picks up one of the scores.

Oh good, good, good, good, good, good, good, good.

As he reads the score, he taps out a rhythm and hums tunelessly. He stops for a moment, looks at his watch, goes to the door and shouts upstairs.

Come on Jack, let’s be having you, we’re up against it!

He returns to his music and starts to sing – badly. Half way through the rendition, RUDYARD’s son JOHN enters. Unnoticed, he listens to his father sing.

‘When I take my morning promenade, Quite a fashion card, on the Promenade. Oh! I don’t mind nice boys staring hard, If it satisfies their desire.

‘Do you think my dress is a little bit, Just a little bit – well not too much of it, Tho’ it shows my shape just a little bit, That’s the little bit the boys admire.’

JOHN. Daddo . . . ?

RUDYARD. At last! Let’s have a look at you.

JOHN. Excellent song.

RUDYARD. ’Tis a good one.

JOHN. Which is it?

RUDYARD. You know it don’t you?

JOHN. Do I?

RUDYARD. When I Take My Morning Promenade.

JOHN. Oh, yes.

RUDYARD. Didn’t you recognise it?

JOHN. Well . . .

RUDYARD. That does not say much for the voice.

JOHN. Perhaps I’d have got it if it was the chorus.

RUDYARD. I absolutely was singing the chorus.

JOHN. Oh. Sorry.

RUDYARD. Anyway.

JOHN. It is usually sung by a woman, so . . .

RUDYARD. Jack – close subject. Let’s have a proper look at you. Aren’t you excited old man?

JOHN. I don’t know what to expect.

RUDYARD. Well, they’ll check you over, they might want a bit of a chat . . . (He looks at JOHN’s suit.) The kit is first-rate . . . where’s your pince-nez?

JOHN. I can’t get to grips with it.

RUDYARD. Well you must. They give a man a different expression as compared to spectacles.

JOHN. It won’t stay on my nose.

RUDYARD. Have you got it about you?

JOHN. I think so.

RUDYARD. Well, let’s have a look – Pop it on.

JOHN. I don’t want to wear it.

RUDYARD. Jack, we need the overall impression. Pop it on please.

JOHN blearily removes his spectacles. He puts the pince-nez on.

JOHN. It doesn’t suit me.

RUDYARD. Yes it does. Turn to the side. Face me. I think it’s good. I wonder if you shouldn’t brush your hair back, away from the face?

JOHN. Why?

RUDYARD. You’ve got a high forehead, it’d be a shame to waste it.

JOHN. What’s a high forehead got to do with it?

RUDYARD. It’s a sign of intelligence.

JOHN. It can’t be.

RUDYARD. I am assured it is . . . here’s a comb – give it a try.

JOHN does so.

Where’s mi baccy? (He locates his pipe.) Let me tell you the programme, you go before the Army Medical Board at three o’clock this afternoon.

JOHN. Who’ll be there?

RUDYARD. An army doctor, probably someone on the board . . . it’s just a preliminary canter, I’m sure it’ll be thoroughly un-daunting. And afterwards we celebrate – we head for the Alhambra.

JOHN has brushed his hair and balanced the pince-nez on his nose, to ensure that it stays in place he has to stand with his head back and his chin in the air.

JOHN. There.

RUDYARD. I like that!

JOHN. What will they want to chat about?

RUDYARD. Well, . . . I tell you what, let’s have a little rehearsal. I’ll fire a couple of basic questions at you, and you answer me as naturally as you can . . . wearing the pince-nez . . .

JOHN. No.

RUDYARD. Why not?

JOHN. Do I have to?

RUDYARD. Of course we don’t have to . . . it’s not for my benefit.

JOHN. Oh don’t be like that Daddo. Let’s do it then, ask me a question.

RUDYARD. Not if you don’t think it’s going to help.

JOHN. I do, I do. Please ask me.

RUDYARD. I think it’ll be useful.

JOHN. It will.

RUDYARD. I’m not doing this for fun. It’s for your sake.

JOHN. I know.

RUDYARD. Alright. First question. John, why are you so keen to join the Army?

JOHN. Well . . . the army needs volunteers . . . I can’t balance the thing . . .

RUDYARD. All the more reason to practice now. Concentrate. Yes, the Army needs volunteers – why?

JOHN. Um . . . it needs volunteers because Germany has been preparing for war . . . for years . . . and . . .

RUDYARD. Specify. How many years?

JOHN. Um . . . (Silence.)

RUDYARD. Well, her intentions were clear as long ago as 1870. 1870 to 1913 is?

JOHN. Um, forty years.

RUDYARD. Nearer forty-five isn’t it?

JOHN. Do I need to say that?

RUDYARD. Absolutely, yes. Facts at your fingertips. Go on.

JOHN. It won’t stay on Daddo.

RUDYARD. It’s good Jack, keep going.

JOHN. I feel ridiculous.

RUDYARD. Keep going.