Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

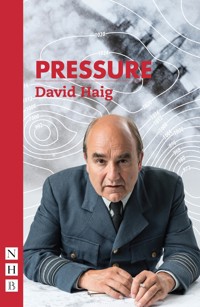

An intense real-life thriller centred around the most important weather forecast in the history of warfare. June 1944. One man's decision is about to change the course of history. Everything is in place for the biggest invasion ever known in Europe – D-Day. One last crucial question remains: will the weather be right on the day? Problematically there are two opposing forecasts. American celebrity weatherman Colonel Krick predicts sunshine, while Scot Dr James Stagg, Chief Meteorological Officer for the Allied Forces, forecasts a storm. As the world watches and waits, General Eisenhower, Allied Supreme Commander, must decide which of these bitter antagonists to trust. The decision will not only seal the fates of thousands of men, but could win or lose the entire war. An extraordinary and little-known true story, David Haig's play thrillingly explores the responsibilities of leadership, the challenges of prophecy and the personal toll of taking a stand. Pressure premiered at the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh, in May 2014 before transferring to Chichester Festival Theatre, in a production directed by John Dove, with the author playing James Stagg.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 131

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

David Haig

PRESSURE

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Original Production

Characters

Pressure

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Pressure was presented as a co-production between the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh and Chichester Festival Theatre, and first performed at The Lyceum on 1 May 2014. The cast was as follows:

DR JAMES STAGG

David Haig

YOUNG NAVAL RATING

Scott Gilmour

LIEUTENANT BATTERSBY/CAPTAIN JOHNS

Anthony Bowers

COMMANDER FRANKLIN/GENERAL ‘TOOEY’ SPAATZ

Gilly Gilchrist

ANDREW

Robert Jack

ELECTRICIAN/ADMIRAL BERTRAM ‘BERTIE’ RAMSAY

Michael Mackenzie

KAY SUMMERSBY

Laura Rogers

GENERAL DWIGHT D. ‘IKE’ EISENHOWER

Malcolm Sinclair

COLONEL IRVING P. KRICK

Tim Beckmann

AIR CHIEF MARSHALL SIR TRAFFORD LEIGH-MALLORY

Alister Cameron

Director

John Dove

Designer

Colin Richmond

Lighting Designer

Tim Mitchell

Deputy Lighting Designer

Guy Jones

Composer/Sound Designer

Philip Pinsky

Video Designer

Andrzej Goulding

The production transferred to the Minerva Theatre, Chichester, on 31 May 2014.

Characters

LIEUTENANT KAY SUMMERSBY

DR JAMES STAGG

ANDREW

NAVAL METEOROLOGIST

GENERAL DWIGHT D. ‘IKE’ EISENHOWER

COLONEL IRVING P. KRICK

CAPTAIN JOHNS

NAVAL RATING

ELECTRICIAN

SIR TRAFFORD LEIGH-MALLORY

ADMIRAL SIR BERTRAM ‘BERTIE’ RAMSAY

GENERAL ‘TOOEY’ SPAATZ

COMMANDER COLIN FRANKLIN

LIEUTENANT DAVID BATTERSBY

And a SECRETARY, an AIDE

This ebook was created before the end of rehearsals and so may differ slightly from the play as performed.

ACT ONE

Scene One

1.00 p.m. Friday, 2 June 1944.

Southwick House, Portsmouth, England. Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.

A large room dominated by floor-to-ceiling French windows leading out to a small balcony. From the balcony, a view of the staggering Naval armada packed into Portsmouth Harbour – battleships, destroyers and landing craft, rail to rail, as far as the eye can see.

A stiflingly hot, summer afternoon. The sun streams through the windows, dust motes in the air. The room looks… transitional, as if waiting for someone to give it a purpose. Piles of wooden chairs, tables, a single telephone. There’s a giant noticeboard, punctured by hundreds of drawing pins, but no notices. Leaning against this wall are two sets of library steps on wheels. There’s an old upright piano in the corner.

LIEUTENANT KAY SUMMERSBY (thirty-five years old) sits at a table by the window, sorting through a huge pile of correspondence. She is attractive, vivacious, the daughter of an Irish cavalry officer. She is also General Dwight D. ‘Ike’ Eisenhower’s chauffeur, unofficial aide and confidante. She is dressed in the uniform of the Motor Transport Corps. The uniform is worn out. The seat of her skirt, shiny from constant driving, her jacket, faded.

KAY, like all the characters in the play, looks unslept. She lifts her head to feed off the warmth of the sun, but her peace is disturbed by the sudden roar of a fleet of bombers passing overhead, heading for the French coast. Their shadows blot out the sun.

The noise of the bombers masks the sound of the door opening. An ordinary-looking man with a tidy moustache enters. He is dusty, sweaty and is wearing an ill-fitting RAF uniform. He carries a suitcase and a briefcase. This is DR JAMES STAGG, Chief Meteorological Officer for the Allied Forces.

He looks around him.

STAGG. I must be in the wrong room.

KAY jumps to her feet.

KAY. Good afternoon, sir.

STAGG checks the number on the door.

STAGG. Room six, first floor?

KAY. Yes, sir.

STAGG. Should you be in here?

KAY. I beg your pardon, sir.

STAGG. Should you be in here?

He takes a sheet of paper out of his pocket and checks it.

Room six. You’ll need to clear your stuff out.

KAY (demanding some sort of normal exchange). How do you do. I’m Lieutenant Summersby.

STAGG. James Stagg. Is there only one telephone?

I’ll need more than that. Who should I talk to?

KAY. I’ll find out.

STAGG (looking around him. Shocked). This is just a room.

KAY. I’ll tell the General you’ve arrived.

STAGG. Which General?

KAY. General Eisenhower.

A moment as STAGG digests this.

STAGG. He knows I’m arriving today.

KAY. Does he? It may have slipped his mind, he’s a rather busy man.

STAGG. It won’t have slipped his mind.

They stare at each other. STAGG, impassive. KAY, annoyed. She spins on her heel and leaves the room.

STAGG immediately removes KAY’s correspondence from her table, dumping it on the floor, then he drags the table further into the room. He does the same with the other table and places a chair behind each.

He takes out a handkerchief and mops his brow, then opens the French windows and goes out onto the balcony. Shielding his eyes from the sun, he looks up at the sky, turning slowly on the spot, he looks north, east, south and west. As a cricketer would check the pitch, so the meteorologist checks the sky.

There is a knock on the door. STAGG returns from the balcony.

Come in.

A young man (ANDREW), excited and out of breath, enters in the uniform of a junior Air Force officer.

ANDREW. Welcome to Southwick House, Dr Stagg.

STAGG. Thank you.

STAGG claims one of the two tables as his own and starts unpacking his briefcase.

ANDREW. It’s a great honour to meet you, sir.

STAGG says nothing. He sets out mathematical instruments and an array of pencils and coloured pens on his table.

I so enjoyed your paper on the Coriolis effect.

STAGG. It’s a fascinating subject.

ANDREW. I’m a great admirer of the Bergen School. Upper-air structures.

STAGG. You’re on the right lines then.

A young NAVAL METEOROLOGIST hurries past the open door, but stops when he sees ANDREW. He hands ANDREW a piece of paper.

NAVAL METEOROLOGIST. Latest thermograms, sir. Stevenson screen two.

ANDREW. Thank you.

The METEOROLOGIST marches off. (Whenever the door is open, we’re aware of voices, footsteps, doors slamming. A constant buzz of urgent activity.)

(To STAGG.) I’m seconded to you, sir, for as long as you’re here, if there’s anything you need…

STAGG (tension in his voice). I need everything. Look at this room. I need an anemometer, a Stevenson screen, thermometers, barograph, barometer, telephones.

ANDREW. Admiral Ramsay has a forecast room downstairs, I’ll see what I can find.

STAGG. I’d be grateful.

The NAVAL METEOROLOGIST returns. He salutes sharply and hands STAGG a rolled-up chart.

NAVAL METEOROLOGIST. Synoptic chart, sir. 1300 GMT.

STAGG takes it.

STAGG. Very good. How frequently are you producing charts?

NAVAL METEOROLOGIST. Every six hours, sir.

STAGG. Normal synoptic hours?

NAVAL METEOROLOGIST. Yes sir. 0100, 0700, 1300 and 1800.

STAGG. And intermediates at 0400, 1000 and 1600?

NAVAL METEOROLOGIST. Yes, sir.

STAGG. Thank you.

The METEOROLOGIST leaves. STAGG wheels a set of library steps to the giant notice board and climbs the steps.

ANDREW. Shall I give you a hand, sir?

ANDREW wheels the other steps over and climbs them. STAGG hands him one end of the chart.

I’m Andrew Carter, by the way. From the Met Office. Flight-Lieutenant Carter I should say. They plonked me in the Air Force, I’ve no idea why.

STAGG. No. (A beat, then:) I’m a Group Captain, I’ve never been near an aeroplane.

STAGG pins the top of the chart.

ANDREW. Good journey, sir?

STAGG. Eighteen miles in seven and a half hours. An average of 2.4 miles per hour.

ANDREW. The roads are impossibly busy.

Short silence.

Apparently, there are so many extra tanks and troops in the country, only the barrage balloons stop Britain from sinking.

STAGG. Aye, so I heard. It’s a fine, sunny day, I should have walked.

ANDREW. Bit warm for walking, sir. We have a screen in the grounds. The midday reading was 92.4.

STAGG has finished pinning the chart.

STAGG. You can let go.

They release the chart which unrolls down the noticeboard. It’s a massive synoptic weather chart, stretching from Newfoundland in the west to Central Europe in the east, from Greenland in the north to the North African Coast in the south. Written along the top is the caption: ‘1300 GMT FRIDAY JUNE 2 1944.’

For STAGG, a new weather chart is like a Christmas present. He is instantly absorbed. ANDREW could be a million miles away. STAGG gently touches the chart, then traces his finger along one of the finely drawn lines.

The chart could be as big as 12’ x 4’, big enough anyway to be seen clearly by the whole audience.

A high-ranking American officer appears in the open doorway below them. He takes a deep drag on an untipped Chesterfield and looks up at STAGG.

IKE. Good news?

STAGG is too absorbed to reply. He glances briefly at the American officer, then turns back to the chart. ANDREW, on the other hand, scuttles down his library steps and slams to attention.

ANDREW. Sir!

STAGG continues to examine the chart, he places his hand over the Arctic Circle.

STAGG (half to himself). Full of menace…

He climbs down a few steps and places his hand on the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

…these are formidable…

He climbs off the steps and pushes them to one side. He places his hand over the Azores at the bottom of the chart.

…this is gentler… but interesting.

IKE. Good prognosis?

STAGG. When Colonel Krick arrives, we’ll confer, then I believe I report to General Eisenhower.

IKE. I am General Eisenhower.

GENERAL DWIGHT D. ‘IKE’ EISENHOWER, Allied Supreme Commander with sole responsibility for the D-Day landings.

ANDREW remains rigidly at attention. STAGG looks genuinely amazed.

STAGG. I thought your voice was familiar. It’s seeing you in the flesh, rather than just speaking to you on the telephone… and in your photographs you seem to have more hair than you actually have.

IKE cannot find a suitable response.

ANDREW (to STAGG). I’ll see what I can find downstairs, Dr Stagg.

ANDREW leaves. IKE closes the door. The buzz of voices in the corridor is muted.

IKE takes a packet of Chesterfields out of his pocket and lights a new one with the tip of the old.

IKE. You got an ashtray in here?

STAGG. I’ve got very little of anything in here.

IKE. Not a problem. What do you need?

STAGG. Everything. A forecast room is a specific environment, this is just a room. It’s certainly not good enough for the purpose.

IKE. Give Lieutenant Summersby a list of what you want.

IKE walks towards the balcony.

I need you to be close. I’m a couple of doors down.

Suddenly his right knee buckles under him.

Goddammit!!

He grabs one of the tables to support himself.

I have a knee. Goddamn!

IKE gently flexes his leg.

Boring! Cartilage. Football injury.

Gingerly, IKE takes a couple of steps.

Not talking about soccer, Dr Stagg, I’m talking about American football… more like your ‘rugby’, am I right? You ever play rugby?

STAGG. On occasion, sir.

IKE. If we ever get a spare moment, you’re gonna tell me what in heck is going on in that game. I saw a match once and I sure as hell didn’t know.

IKE limps out onto the balcony. He stubs out the old Chesterfield with his foot.

What a beautiful day. Flaming June!

What part of Scotland are you from?

STAGG. Dalkieth, sir. A wee town by Edinburgh.

IKE. God I love that city! First time I saw the castle on the rock – man! I’m from Kansas, I didn’t see a hill till I was twelve years old.

IKE takes a deep drag on the new cigarette and blows smoke into the blue sky. He looks down at Portsmouth Harbour.

Seven thousand Naval vessels, Dr Stagg.

He turns back to STAGG.

Seven thousand vessels, one hundred and sixty thousand ground troops, two hundred thousand Naval personnel, fifteen hospital ships, eight thousand doctors, four airborne divisions. The biggest amphibious landing in history. And let me tell you, every piece of the jigsaw is in place. Every man and woman involved is ready and waiting. There’s no more to learn. It’s time to run with the ball. But… there is still one uncertainty, one imponderable that can stop this thing happening… that’s why I’ve put you in this room. I want you right beside me for the next four days.

STAGG. I worry…

IKE. Not your job.

But STAGG persists.

STAGG. I worry that what you require of me is scientifically impossible.

IKE waits for STAGG to continue.

Long-term forecasting is only ever informed guesswork.

IKE. Monday isn’t long term, for God’s sake.

STAGG checks his watch.

STAGG. Sixty-five hours to go. In this part of the world, anything more than twenty-four hours is long term.

IKE. You listen to me, soldier. Your Met Office tells me you’re a genius, you’re tearing up the rulebooks. I don’t care how you do it, but I’m relying on you and Colonel Krick to tell me if the weather’s gonna be good on Monday.

STAGG. And on Sunday I will be able to offer you a degree of certainty.

IKE. Sunday’s too late, goddammit. I need to know now. You got me?

STAGG is silent.

We’ve got one chance, Dr Stagg. One chance only to get this right.

IKE walks towards the door, still limping slightly.

Ask them to bring up a bed, you’re gonna need it.

IKE is almost out of the door, then he turns back.

For the next four days, you’re part of the family. Same team, same ‘end zone’. Pardon me, wrong game. What would you call the end zone?

STAGG. The try line?

IKE. Sounds good. Same team, Stagg, same try line.

IKE leaves, closing the door. STAGG mops his brow again. Another fleet of bombers roars overhead.

STAGG opens his suitcase and takes out a framed photograph of a heavily pregnant woman holding a child. He stares at the picture for a moment, then sits at his table, placing the photo in front of him.

He concentrates on the chart on the wall and starts to make notes.

A knock on the door.

STAGG. Come.

KAY enters.

KAY. I’ve brought the ‘little blue book’.

She flicks through to the correct page.

If we lost this, the Allies would probably lose the war! Your first meeting will be at 1500 hours. General Eisenhower, Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, Admiral Ramsay and General Spaatz will be present. They would like to meet you here. In this room.

STAGG nods, concentrating on the chart. He changes pencil and draws a series of lines.

Does that give you enough time?

STAGG. If Krick arrives soon.

Silence. STAGG continues to draw lines, rub them out, refine them, make notes. KAY watches him work. KAY is not sure whether STAGG is talking to her, but suddenly he expresses his thoughts out loud.

What he ignores is the third dimension, vertical structures, the upper air. This jet is thin, rapid, straight. No meandering, no Rossby waves. Freezing tongues of disruption pushing south. Vicious extrusions of cold air. He cannot ignore that.

KAY. Who’s ignoring it?

STAGG looks up, surprised. He had forgotten KAY was in the room. He stares at her, then returns to his work.

STAGG. Sooner or later, the Arctic air will penetrate the westerly flow. L2 and L3 will be reinvigorated. But he won’t see it.

STAGG falls silent again, making further notes. Then, suddenly:

I sent Flight Lieutenant Carter in search of equipment. There’s been no foresight at all, the set-up’s amateur! These tables should have sloping tops, I need paper, ink, pencils, thermometers, barograph, barometer… telephones, I must have more telephones.

KAY. I’ll see what I can do.

STAGG. It’s urgent.

KAY. Everything, Dr Stagg, is urgent. I’ll do my best.

It’s at this moment that KAY notices the correspondence she was working on, piled up on the floor. She marches over and starts to pick it up, placing it on top of a filing cabinet. She is furious, but her tone is controlled and polite.

Dr Stagg, this is the Supreme Allied Commander’s personal correspondence. These are heartfelt, handwritten letters, sent from all over the world to General Eisenhower…

The NAVAL METEOROLOGIST enters and hands STAGG some papers.

NAVAL METEOROLOGIST. Radio soundings for the past twenty-four hours, sir. From weather ships Dog, Baker and How.

KAY continues brightly: