NER-A-CAR E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

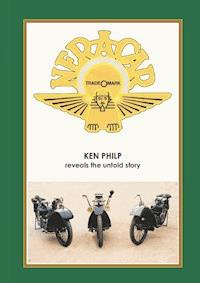

Life-long motorcyclist Ken Philp reveals the story of the Ner-a-Car in England. Reference is also made to the American story. There are over 50 black-and-white illustrations, many from the 1920's. There are also over 50 colour photographs, depicting the machines during restoration, and both them and others being ridden in recent years. The brief restoration accounts involve a 1925 Model C and a 1925 American model. Other references are made to the restoration of a 1921 Model A and getting a 1926 Model B ready for the road after many years in a Museum.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 182

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents.

About the Author.

Foreword

Acknowledgements.

A little about my motorcycling life

How it all began

NN 4411

Further Research.

The Origins of the Ner-a-Car.

Early Production – 1

Harry Hollins Powell.

Early Production – 2

First Production.

Finningley.

What Happened at Finningley?

The man in the photograph.

The Inter-Continental Engineering Company Ltd.

Kingston-on-Thames.

Success!

The Chassis and Other Cycle Parts.

Engine Sizes and Types.

The Friction Drive.

The Hub-centre Steering

Models Made In England

Numbers produced

Differences in the American models.

Design Changes.

Contrasts

The end of production.

Mrs. Janson.

Cannonball Baker

Ner-a-Cars in other competitions

Experiences in Restoration.

Riding Impressions.

…and finally, into a new millennium!

Conclusions

Supplement.

List of Museums That Have Neracars.

Bibliography.

About the Author.

Ken Philp trained as a Marine Engineer, and then moved on to Power Stations. He followed this by transferring to the associated Transmission Grid System, where he spent many years as a Grid Control Engineer, before retiring at Privatisation.

In all that time he has always owned and ridden motorcycles, but has never been deeply involved with vintage models until he was offered the chance to get involved with his friend’s Ner-a-Car.

This is his first attempt at writing a book.

The Author with the Ner-a-Car Model B kindly loaned to him by Kelham Island Industrial Museum, Sheffield.

Foreword.

It was not my intention originally to try to produce a complete history of the machines and factories but this offering has accidentally ended up part way down that road. So much new information has come to light that it feels like a duty as well as a pleasure to record and pass it on, especially as it corrects a few widespread items of misinformation. It is mainly concerned with the English production, although there will be references to the American operation where necessary. It is also an attempt to resolve anomalies and errors that I have come across during that time. It is as accurate as possible, and where there is some doubt then I have expressed it.

My involvement has been principally with four machines, a Model A of 1921, a Model B of 1926, a Model C of 1925, and an American-built 1925 model sold when new in France. Some of the technical details that are unusual, and sometimes baffle those who are not familiar with these machines, will be described as simply as possible, with photographs where appropriate.

Acknowledgements.

My thanks go to Terry Smith, the owner of the Model A, who really set me off on all of this! He gave me my first ride, and access to his well-restored machine for some of the photographs.

Also to G. Stuart Mayhew, the owner of the Model C and the American model. (Stuart is also the proprietor of North Leicester Motorcycles, the foremost Moto Morini dealer.) I have been privileged to have an almost free hand with these two machines, which has been greatly appreciated. Stuart has also encouraged me to complete this, and has acted as proofreader. His son, Alex, has also been a great help with computer programming.

I am indebted to Miss Powell and her relative, Mrs. Knight, who have kindly given permission to reproduce all the information that I have been privileged to see.

Carl Neracher Morris and his cousin, Marcia Gilfillan Diehl, have been very helpful with photos from the 1920’s era.

The Local Studies Library, Sheffield Libraries, Archives and Information, through Mr. D. Hindmarch, also gave permission to reproduce the photographs of the Ner-a-Car production line and factory.

Mr. Cedric Blaker allowed me to reproduce his prized photographs of Mrs. Janson.

I am extremely grateful to Fiona Elliott and Dennis Dawson, Curator and Engineer respectively of the Kelham Island Industrial Museum, Sheffield, for the loan of the Model B, which gave me a ride in the 2001 Banbury Run and other outings.

My son, Martin, has taken quite a lot of time to provide some of the photographs. Others who were very helpful were Chris Brown, Damon and Natalie Dardaris, Malcolm Dungworth, Tony Dymott, Brian Lilley, Peter Miller, Steve Myers, John New, Bernard Owens, Mr. and Mrs. Rowley, Geoffrey Stein, Mr. A.G. Taylor, Frank Wood, and Geoff Wren. There are probably others, so if I’ve missed you out, please accept my thanks.

I must also give heartfelt thanks to my wife, Pat, who dusts around the paperwork that I have collected in our back bedroom for the past few years, and who has at times taken what to her were boring messages. She has also patiently listened to me chattering on about many details that excited ME but not her!

A little about my motorcycling life.

I was born and brought up in Cornwall, and inherited my lifelong interest in motorcycles from my father and uncles who had been motorcyclists in their younger years. My father, in fact, had his first “get-off” at the age of 15 when trying to prove that his older brother’s 350 2-speed - a New Imperial - was quicker than his mate’s 250 3-speed. He had just passed the 250 when the front tyre blew up! I still have a photo of that bike.

My own riding started back in my teens, in the 1950’s. My father allowed me to learn on his BSA Golden Flash and sidecar. Over the years I have had several bikes, nothing very exotic, but a few unusual machines, such as a Heldun Hammer 50 c.c. scrambler, and even a Francis Barnett Fulmar into which I hung a British Anzani 250 c.c. 2-stroke twin. The oldest and most exotic was a 1939 Scott 600 c.c. Clubman Special - I remember it had plunger rear suspension with solid brass sliders and the extra cylinder barrel oil holes to be fed by a second Pilgrim pump. Pity I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but I was only 19. My father got it for me while I was at sea - it cost just £15. It had to go because it occasionally boiled over, and then split open the radiator. I didn’t realize back then that it just needed new crankshaft seals!

My riding has been varied, but a lot has been off-road. In the mid 1960’s I rode a Cotton fitted with a British Anzani 2-stroke twin in Southern Centre trials. I then had a Sprite Trials 197, a self-assembly kit to avoid Purchase Tax, uprating it to a 250 later. A Triumph TRW was another converted to use off-road, then a BSA B40 followed this. I helped at several Welsh Two-day Trials on these, route marking and course opening/closing in the 1970’s and early 1980’s. Another machine of note was a Greeves Scottish into which I fitted yet another British Anzani. I told you that some were unusual!

Of the bikes that I’ve owned, I’ve never been glad to see the back of any of them. I now own two Moto Morinis, a Kanguro trail bike model that I rode in Fun Enduros for 7 years, and a Dart sports model, both fitted with the 344cc veetwin.

My father and uncles always said that the Ner-a-Car was most unusual, and that it’s handling was excellent - indeed, that’s all that they mentioned about it, along with the fact that it had hub-centre steering. I often wondered about it, but never had the chance to play with one - until recently, that is.

Terry started to restore his Model A with nothing more than this.

How it all began.

In the mid-1990’s a friend of mine, Terry Smith, acquired a Ner-a-Car. When I first saw it I was by no means impressed. You will appreciate why when you look at the photograph.

I thought that it was almost impossible to restore, so didn’t show much interest. Terry used to talk about the problems encountered during restoration, and then showed me some of the pieces that he had made from cardboard patterns copied from another machine. His workmanship was exceptional, and it was obvious that it would end up in excellent condition. My interest was naturally increased.

One thing that was missing was the Chassis number plate. This is a brass plate screwed onto the chassis on the left side just below the rear of the petrol tank. On Terry’s, the screws were there, with remnants of the plate ends, but the middle section with the number had been ripped off during the 75 years that it had lain idle. The turning point for me was that I was offered the opportunity of being the Test Rider on completion provided that I traced the original Chassis number! As you can imagine, it took me a whole nano-second to agree, being a lifetime motorcyclist. I had a little experience of this type of research with a Greeves Scottish about 20 years ago, only in that case I didn’t have the Registration number, but was successful after about 3 months research.

So I started my research. It led to more than just tracing the Chassis number. My interest has grown and grown over the years as I’ve found out little snippets and have been led down other avenues connected with the machines. Now it has led to this attempt at passing on the accumulated details of the Ner-a-Car.

All because I started looking for a Chassis number!

The first and last early tax disc.

Reading the reverse is interesting! This is why we believe it was only on the road for eight months.

Note the reply from the Local Taxation Office in 1961.

NN 4411.

What a nice symmetrical Registration Number!

Going back to the late 1950’s, Terry had seen this bike in roughly the condition in the picture, in a local motorcycling garage. He was offered it for £2, but he refused because, when the owner told him the make, Terry didn’t really believe him! Just after that it was bought – for £4 – by an acquaintance of Terry’s. (Terry was passed the receipt with the bike.)

When Terry got the bike there was a little information about it, but not much. Nothing had been done to it in the intervening 35+ years. Happily, we knew the Registration Number, and knew from that that it was a local machine. It also had a Tax Disc from 1923 with it that turned out to be the only one it ever had!

The engine number was also plain to see on the crankcase. The previous owner had attempted to obtain duplicate documents in the early 1960’s, but was refused – note the official written reply shown opposite. The previous owner DID manage to get it onto the computerized system later on, however.

The first line of inquiry was obviously the D.V.L.A. but this was unfruitful. So I visited the Local History Archives, which sometimes have the details of the original Registration Application, passed to them when the Local Vehicle Registration offices closed down. This was fruitful in one sense, because, while the details of Terry’s machine were not there, the details of the vehicles each side of Terry’s Registration number were there. This confirmed the date of original Registration as being that on the Tax Disc. Thus, we originally dated it as a 1923 model – wrongly, as time would tell.

Still no sign of that Chassis number, though.

Further Research.

Along with the bike there was some information from magazines such as Classic Bike and Classic Motorcycle. I also got information from the set of books called The World of Motorcycles, which is made up from the bound volumes of the mid-1980’s magazine On Two Wheels. One of the next actual visits was the Vintage Motor Cycle Club library, where I found quite a lot of information from contemporary magazines such as The Motor Cycle and Motor Cycling.

However, there was some conflicting (and sometimes incorrect) information in nearly all the sources of written details that I investigated, which is one of the reasons why I became more determined to find out more about them. One somehow expects machines displayed in Museums to be accurately restored, but it became apparent that this could not be relied upon as some of the models were wrongly finished, or the information with them is incorrect, or the machines are incomplete.

Places that I’ve been to in an attempt to get accurate information are the Public Records Office at Kew, the new British Library, Sheffield Local Studies Library, Sheffield Archives, Kelham Island Industrial Museum at Sheffield, and some of the original factory sites. I’ve also been through a few old newspaper archives to verify “hearsay” reports.

I’ve also contacted other Museums, office addresses, and Local Studies Libraries, and got into contact with American enthusiasts who have an interest in the bikes. I even contacted Companies House, and Customs and Excise – the reason for the latter will be given later.

So read on to find out how I fared, and whether I earned my ride by finding the Chassis number.

The Origins of the Ner-a-Car.

Photograph of Carl Neracher circa 1920.

One thing that IS well known is that the Ner-a-Car was designed by Carl A. Neracher, (pronounced NERacker). He had a background in automobile engineering, and as such he brought car practices into his design, such as a pressed steel chassis, and hub-centre steering operated by a drag link. The name, too, reminds one of a car, “near a car”, as well as it being a slight alteration to his name. The exact date when it was designed is not known, but is thought to have been about 1918.

The earliest Patent Applications seem to have been in 1919 in the U.S.A., but apparently these were not granted until machines had been in production for about 4 years. As far as British Patents are concerned, there are two granted to Neracher, one in late 1920, and another in early 1921. The numbers are 155862/19 and 158702/19. These were noted on the original transfers that adorned the first models of machines made in England, but not on later models.

The original American design consisted of a pressed steel chassis with hub-centre steering, a low saddle, footboards, and fitted with a 2-stroke engine. The front mudguard was quite large, fixed to the chassis, and provided good protection from the elements. The transmission was by friction drive from the rear of the flywheel – both this and the hub-centre steering will be described later together with photographs.

That basic design continued throughout its production both in America and England without major changes, although English models had a number of differences from the American ones. A greater range of models was also built over here, as we shall see.

According to J.Allan Smith, whose involvement is discussed later, the intention was to produce “a machine weighing less than 200 pounds which could be ridden by either lady or gentleman in any costume without injury to their attire from mud or grease.”

All this, but I’m no nearer to finding the Chassis number.

Early production – 1.

My quest for the Chassis number was still on and, with no success in this country so far, I wondered whether the early machines in England were imported. So where could I get information about Imports? Customs and Excise was suggested, remember I mentioned them earlier. Apparently it would be possible with some items if the records were still available, but would be a mammoth task involving checking through Bills of Entry at the Port that may have imported them, and I had no evidence of anything like that. So that was discounted.

The next place to try would be America, if they were made there. I wrote to the Syracuse Chamber of Commerce, Syracuse being the town where they were produced. They passed my letter on to the Onondaga Historical Association. They were very helpful, in that they sent some copies of newspaper cuttings, and put me on to two people who have a lot of information on the machines, and have a small museum. They are Frank Westfall, and Damon Dardaris. Damon and his wife Natalie are my contacts, and they, too, have sent relevant cuttings. Some of the following information comes from them. They also put me in contact with Geoffrey Stein, who has done a tremendous amount of research on Ner-a-Cars – he is an Associate Curator in the History Department of New York State Museum. We have exchanged a little information, and I thank them all for their interest and assistance.

As Carl Neracher was American it is natural to think that production started over there. To discuss this we have to go back to the period before 1918 and talk about someone who was instrumental in getting production up and running. That person was Joseph Allan Smith.

Joseph Allan Smith was what we would call a high-flier today. He was a leader and manager who moved relatively quickly from one position to another. By 1918, at the age of 45, he was President of The United States Light And Heating Company, of Niagara Falls, with an office in New York. I thought that this was probably a generating Company, but when I eventually got a letterhead from 1908 it says “Railway Trains Electrically Lighted, Heated and Ventilated From Car Axle. Country Residence Lighting and Heating.” He was also President of the New Process Gear Corporation of Syracuse at the same time!

J. Allan Smith. This is believed to have been taken on board ship during his trip to England in 1919 with Carl Neracher.

Copy of a letterhead stating the purpose of the U.S. Light and Heating Co. It also makes the connection between Allan Smith and Harry Powell – his role will be discussed in a later chapter.

Vintage motorcyclists in England have no doubt heard of the Wall Auto Wheel. The American magazine MotorCycling and Bicycling, in its issue of March 29th 1922, referred to this and said that this (quote) “had the financial backing of the author, A. Conan Doyle, and a London banker. The London banker requested President Smith to dispose of the manufacturing rights of the Wall Auto Wheel in the States. This effort resulted in the compilation of statistics which in turn resulted in Smith’s interesting the Chief Engineer of a prominent automobile manufacturing company.”

The magazine then continues to say that these statistics “interested Mr. Smith and his friend, the engineer, to such an extent that various types of foreign-made machines were studied and tried. The engineer designed a lightweight machine which is now in production in this country.”

Thus the Neracar was born, Carl Neracher being the engineer!

However, it would seem that they had difficulty in arousing interest, and thus financial support. The Ner-A-Car Corporation was set up in New York State in April 1920, with the first offices in a Syracuse hotel. There was no immediate factory, and hence no production, until the factory premises was occupied at South Geddes Street, Syracuse, New York State, in May 1921. I have included a poor photocopy of that building overleaf. Note the name on the building – In America the motorcycle is the NERACAR, with no hyphens. The NER-A-CAR Corporation has the hyphens.

By this time it would seem that the money was available, with several wealthy backers on the Board. The only one we would recognize in England was King C. Gillette, of the Gillette razor. Apparently he was photographed in 1922 on a Ner-a-Car celebrating his 67th birthday.

Factory building at South Geddes Street, Syracuse, N. Y.

Production was further delayed, though. It was scheduled for November 1921, but apparently some of the tooling gave problems, which delayed the appearance of the machines for early 1922. Even in March delays were being experienced, reportedly due to the non-supply of a suitable rear mudguard. The above-quoted magazine mentions this delay. Production must have got under way just after this, as there are several reports of successful rides in America later in 1922.

So, was this the first time and place that they were produced? Or do I need to look elsewhere to find the Chassis number? To answer this we need to go back a few years again, and consider how they came to be produced in England.

Harry Hollins Powell.

For me, this is the most important new part of the story in the English history of the Ner-a-Car. Harry Powell’s name had never come up in any writings that I had come across previously, nor had anybody mentioned him in conversation.

H.H.Powell. This is a similar photograph to the one in his 1919 Passport.

When I received information and some pictures from Damon and Natalie it was fairly obvious that there was a difference between the American models and Terry’s. So was his machine made in England, not imported? The idea that it was an import had come about because of the remains of a transfer on Terry’s bike. I hadn’t seen this transfer before he prepared the front mudguard for painting, which removed all traces, but Terry said that it said something like “Intercontinental Engineering”.