Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Luca Caioli

- Sprache: Englisch

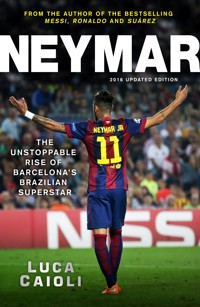

FROM THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF MESSI AND RONALDO Tipped for greatness from an early age, it's easy to think that every moment of Neymar's life has been played out under the glare of a spotlight. But did you know that Real Madrid were just €60,000 away from signing him in 2006? Or that a phone call from Pelé stopped Neymar leaving Santos for Chelsea in 2010? Or that his move to Paris Saint-Germain in 2017 caused tension with his new teammates? Find out about all this and more in Luca Caioli's tirelessly researched biography, featuring exclusive interviews with those who know him best, including friends, family, coaches and teammates. Includes all the action from the 2017/18 season and the 2018 World Cup

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

NEYMAR

Updated Edition

LUCA CAIOLI

Contents

Chapter 1

Prose and Poetry

A conversation with José Miguel Wisnik

Who are the best ‘dribblers’ in the world and the best goalscorers? The Brazilians. It goes without saying that their football is football poetry: it revolves around dribbling and goals. Catenaccio [an extremely defensive style] and triangulation represents football prose: it is based on synthesis; a collective and organised game, i.e. reasoned execution of the football code.

Writing in a 1971 essay entitled ‘Il calcio “è” un linguaggio con i suoi poeti e prosatori’ (‘Football “is” a language with its poets and writers of prose’), Pier Paolo Pasolini, film director, writer and great football fan, set out the similarities between literary genres and styles of playing football, offering a significant distinction between football poetry and football prose: a dichotomy which José Miguel Wisnik, Brazilian musician, composer, essayist and professor of Brazilian literature, uses as the basis for his analysis of the game he so dearly loves. He is a huge fan of Santos.

His reasoning is set out in a book, Veneno remédio: o futebol e o Brasil (‘Poison remedy: football and Brazil’), published a few years ago. Today he reflects on what Neymar means, or what he could mean, for the history of football in his country. This is a player whom he jokingly describes as ‘the Baudelaire of football’. Sitting comfortably in his study in São Paulo, he takes his time before the verbal floodgates open.

‘Brazilian football created a tradition which is based on the ellipse, a style of play which consists of creating non-linear ways of occupying space and breaching the defence. I based my ideas on what Pasolini wrote about football prose and football poetry. We say that football prose is more linear, more tactically responsible, collective, defensive; it involves counterattack, triangulation, cross-overs and rational movements. The idea of football poetry is that of a football which creates new spaces out of nowhere in a non-linear way, using dribbling as the deciding factor. It can be used to penetrate the opponent’s space or just to be effortlessly beautiful or effective. It can be a means to an end or a way to get to goal. Mané Garrincha, for example, took dribbling to the extreme but at the same time was very effective. In the history of Brazilian football, there were glorious moments where dribbling was just for the sake of it but at the same time effective.

‘In the 1930s, when Gilberto Freyre analysed Brazil from a sociological, anthropological and historical perspective, he noted that the identity of Brazilian football was closely linked to the identity of the half-caste people. The Brazilians took the English choreographed, formulaic style and turned it into more of a dance, mixing nifty footwork and capoeira and samba dance skills. This obviously has had a huge impact on how our culture is interpreted: the idea that efficiency is only valued if it is accompanied with pleasure; in other words, the ideal situation is bringing together the concepts of work and partying. Brazilian football, in this context, is both the poison and the antidote because it is a form of cultural realisation like popular music or carnival, but it is also a problem because it promotes the idea that our culture glorifies laziness and gratuity over efficiency.’

Can we go back to the concept of football and poetry and how it takes us to Neymar?

‘Sure. That was just an introduction. So, Brazilian football gave a style to English football which Freyre defines as curvilinear and Pasolini poetic. A style of play which was developed in South America in the 1960s and reached a climax in the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. At this time, Brazilian football created a repertoire of non-linear moves which can be considered as ellipses, a concept of both geometry and rhetoric. Moves which are based on curves or freezing of time. Just think about all the various types of dribbling: dummies to the left, shimmies to the right, fakes, using the moment to beat your opponent in a static situation. Also the one-two, the lob, the “falling leaf” where the ball would deftly swerve downwards just at the right time. A classic repertoire which existed in Brazilian football from 1962 to 1970. It then existed only as a trait or style but from the 1970s onwards Brazilian football adapted to the new reality in international football, i.e. physical and athletic fitness, team play, different formations and specialisation of attackers and defenders.

‘In the World Cups of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, Brazil tried various solutions. The football poetry was still there somehow, with players like Zico, Sócrates and Falcão playing in 1982, or with Romario, who in 1994 still played ellipse football in a national team which had adopted a more prosaic style. Up until the arrival of Ronaldinho, a footballing genius who brought back the entire repertoire of Brazilian football. You could see Didi’s “falling leaf”, Pelé’s lob or Garrincha’s dribbling. Ronaldinho was an artist of mannerisms, almost as though he was “quoting” other players’ famous moves. Ronaldinho is well aware of this and as an author quotes another writer, he “quotes” a goal of a player from the past.’

And now we get to Neymar …

‘Yes, all of the above was to get to Neymar. In a time when no one believes a poetic tradition exists and that it is disappearing even in Brazil due to a tendency to play football prose, along comes Neymar. A player who represents someone who wants to keep this poetic style alive.

‘Neymar has an extraordinary dribbling repertoire. Impressive, I would say: a repertoire that shocks you with its inventiveness, its freshness. It is pure ellipse football. If you don’t believe me, watch the dribbling with his heel against Seville in one of the first games of the [2013/14] Spanish league season: something unexpected, which no one even dreamed of.

‘At Santos, from when Neymar was thirteen years old, he was marked out as the future champion. He is part of a generation which has been trained and grown to be something important. Often important groundbreaking news does not live up to the hype. Neymar, however, completely lived up to the qualities that were ascribed to him. In addition to his magical ability on the ball, he has a natural charisma, extraordinary likeability and the ability to manipulate his public image, just like a pop star. He has conquered the hearts and minds of girls and the public alike and is acknowledged by other clubs’ fans and by great players from the past and present. In his years at Santos he showed all his exuberance, all his ability to dribble the ball, thus confirming that the tradition continues with him.

‘Yes, Neymar is a poet, a graffiti artist: his sonnets are daubed all over the city’s walls. His hair, his way of putting his shirt collar up and his celebrations are all part of his poetic performance. Neymar is a sort of modern-day man of the people, full of energy and life and an absolute star of the current era. He has great vision on the pitch, he has killer passes and he has a superb ability to capitalise on opportunities. He is not just a great dribbler; his relationship with dribbling is not merely rhetorical, as with Robinho who was a poor finisher and whose one-two passes were often just for effect. Neymar has a technologically advanced style, intricate but frighteningly effective. Efficient but without losing its appeal for the spectator. It is on another level, brand new and gives a new dimension to poetic football.

‘I see him being in a very interesting situation. Much has been said about him being able to adapt to the Seleção [Brazil’s national football team]; he proved this during the Confederations Cup. La Canarinha [another nickname for the national side] has found a style of play which exploits Neymar’s potential to the maximum. The great expectation is how he will fit in at Barcelona. Santos managed to keep him until 2013. Seeing that a player who was at the height of his powers was not sold to a European club or an East European club straightaway was important for Brazil’s self-esteem. To be honest, at Santos he was left to his own devices and I hoped he would go to Barcelona to mature in international football.’

Can Neymar’s poetry and Barcelona’s prose fit together?

‘Barcelona’s football is not football prose. It is a complete mutation in how to play football in that it combines occupation of space and expansion of the area of play on the wings, which echoes the Dutch style of play, with South American football traits such as the tiki-taka heel flick. You could define it as football written in prose, extremely agile but not overly structured. The presence of Messi and the dribbling which pierces the defence leaves one in no doubt of the determining presence of South American football. I believe that Barcelona, in its great moments, has squared the circle. To bring together prose and poetry, to bring together European football and South American football and to go beyond football’s classic dichotomy. What will happen now there is Messi and Neymar? They have different styles. Messi’s dribbling is not as exuberant as Neymar’s: it is efficient; there is a sense of mystery about the way he moves forward with the ball – you can hardly tell how he does it. He does not move like a Brazilian. His intuition is out of this world, he has a sixth sense for when his opponent is about to present him with an opportunity or when space is opening up. Messi is the straight line to Neymar’s ellipse.’

Chapter 2

Mogi das Cruzes

Chaotic traffic: scooter and motorbike horns blasting. Flyovers, skyscrapers, low-level housing, viaducts searing above traffic jams, industry, roadworks, favelas. São Paulo, a megalopolis with 11 million inhabitants, seems to go on forever; it seems to want to keep visitors in its clutches and not let them go. The city spreads along the three-lane Rodovia Ayrton Senna, the newest of its kind in the country, dedicated to the eponymous national hero and São Paulo racing driver who died during the Imola Grand Prix on 1 May 1994.

The bus leaves from the Rodoviario de Tiete Terminal (the largest in Latin America and the second largest in the world after New York), with passengers scurrying here and there as they go on their way. The bus is perfectly on time but struggles to get out of the city traffic jams; it scrapes past lorries and cars which dart in and out of the lanes. A toll booth, and it changes motorways. As it heads for Itaquaquecetuba, the city finally lets the bus out of its clutches into the open countryside, which is green and with a plethora of hills that look as though they were sketched out using a ruler. Kites fly high in the sky and bone-dry, dusty football pitches, dotted between the vegetation, mark the favelas clinging on to the hillside: red bricks that look like they have been stuck together by a kid playing with Lego, makeshift roofs, satellite dishes, large sheets to cover construction works that have never been completed. Stagnant water, burnt-out cars, kids crossing the motorway on their bikes to get back home with their shopping.

Then the sharp downhill of Serra de Itapey. At the bottom, the skyscrapers of Mogi da Cruzes, one of the Alto Tiete municipalities, an area to the east of greater São Paulo. It was here that Neymar Santos da Silva played football, and here where his son, Neymar Junior, was born: a place with 40,000 inhabitants, its population having doubled in the last fifteen years as commuters have flooded in. They live here and every morning head off to work in the capital; every evening, on the platform at Estação da Luz in São Paulo, they wait patiently to be squashed into the carriages on Line 11 of the Companhia Paulista de Trens Metropolitanos, a creaky and rickety local train which takes them home.

At least there is work in Mogi, where industrial behemoths such as General Motors, Valtra (manufacturers of tractors), Gendau Group (steel works) have plants and employ a large portion of the population. The tertiary sector boasts companies such as Tivit and Contractor, two of the largest telemarketing companies. Agriculture is booming: vegetables, mushrooms, persimmon fruit, medlar and flowers (principally orchids). Stunningly beautiful examples of the latter – in an explosion of colours, whites with shades of fuchsias, violets and lilacs such as the Olho de Boneca (Dendrobium nobile) – are on show in one of the town’s tourist attractions: the Orquidario Oriental. ‘Oriental’? Yes, you read right: the East.

At the start of the 20th century, Mogi experienced an influx of immigrants from Japan: men and women who worked in agriculture, horticulture and trade. They created a lively and flourishing community that did not lose touch with its roots: there are monuments, restaurants, cultural associations, festivals, schools, and the town has been twinned with Toyama and Seki. It is a shame that Torii, the Japanese-style gate, symbol of the Japanese immigrants, which was situated at the entrance to the town, was taken down in the spring of 2013 for health and safety reasons. The heavy rains had severely damaged it.

Luckily, one of the other icons of Mogi has not been ruined by the bad weather. A massive shiny sculpture in stainless steel, towering thirteen metres into the sky, at first sight it looks like Don Quixote from La Mancha but it is actually an homage to Gaspar Vaz for the 450th anniversary of the founding of the city. Gaspar Vaz was the rusher who opened the way to Mogi from São Paulo and founded the town in 1560. From Avenida Engenhiro Miguel Gemma, where there is a shiny statue of the adventurer who came to the area looking for gold (or natives who he could turn into slaves), the bus reaches the Geraldo Scavone terminal in a few minutes. Exactly one hour to travel around 50 kilometres between São Paulo and the town.

Through the cobbled streets of Vila Industrial and we arrive at Estádio Municipal Francisco Ribeiro Nogueira, better known as Nogueirão. The large gate is shut but someone comes and opens it. This is the home of União Mogi das Cruzes Futebol Club, a club which celebrated its centenary on 7 September 2013. It was founded by Chiquinho Veríssimo, a white textile tradesman, and Alfredo Cardoso, a black shoe-smith. The club was born on Brazil’s Independence Day. The football kit is red and white or completely red, with a Tiete valley snake for its mascot (Mogi in the local native tongue means ‘the river of the cobras’).

União is one of the oldest footballing clubs in the region. Over its long history, it has seen the first touches of players like Cacau (now playing for Stuttgart), Maikon Leite (now playing for Náutico) and Felipe (now playing for Flamengo). It has always been a club which fluctuates between amateur football (in 1947 it was champion of the regional Amador tournament) and the lower Brazilian leagues.

Its golden era was from the 1980s to the start of the 90s, when it fought for promotion to the first division of the Paulista league. However, it did not make it and the only league title it has won is the 2006 Campeonato Paulistão Second Division title. Three years later came its worst year ever: União, or Brasinha as it is known in the town, became ‘the worst team in the world’: eighteen defeats in nineteen matches and 75 goals against, a record which relegated the club to the fourth division. Today it is not doing much better, in terms of either its results or its finances – in fact the situation is so bad that the centenary celebrations were a washout. Senerito Souza, the chairman of the club, said better celebrations may be held in the future.

Meanwhile, the players train for the next league match. At 11.30am the first team play a friendly against the reserves. The sun beats down and the red-brick chimney stack on the far side of the stadium casts its shadow over the green pitch.

On the pitch, behind the metal fencing that separates the pitch from the stands (which can take up to a maximum of 10,000 spectators), sports manager Carlos Juvêncio, or ‘Pintado’ (‘painted’ – due to vitiligo which left white blotches on his beautiful black face) watches over the youngest players. When the players get to the changing rooms, I get the chance to have a chat with him.

‘How was Neymar da Silva Santos O Pai, Neymar Jr’s father, as a player?’ I ask.

Pintado replies, ‘A good forward, a number 7. He played on the wing; he was quick, skilful, good at dribbling, he always targeted his opponent. He was a cheery chap, extrovert, a nice person, easy to get on with.’

It is a view shared by his ex-teammates, such as defenders Montini and Dunder and goalkeeper Altair. Everyone agrees that Neymar was good with the ball at his feet. An old-fashioned forward who did not score many goals but was good at playmaking and crossing the ball.

Things change when I pose a question about the skills of both the father and son, about what Neymar Jr has inherited from his dad. Pintado, who played alongside ‘Pai’ in 1993 and 1994, wearing the number 3 shirt for União, well remembers Neymar Jr from when he was just a little boy: ‘Pai brought him to training. He was the team mascot.’ He recalls how both father and son had the same touch and ability to dribble; Neymar Jr was quicker though, lighter on his feet, faster, more creative. Ex-Seleção goalkeeper Valdir Peres, who played in the Spain World Cup in 1982 and was União coach in 1993 and 1995, is of the same opinion. ‘Neymar Jr,’ he says, ‘is a better dribbler and always looks to finish off his moves and score goals.’ ‘He has a better technique,’ adds Lino Martins, who at the end of his professional career played at União with Neymar Pai and then coached Neymar Jr in Santos’s Juniors team.

Neymar da Silva Santos arrived at União Mogi in 1989. He was 24. He was born in Santos on 7 February 1965, the middle son of Berenice, a housewife, and Ilzemar, a mechanic. He has a brother, José Benicio, or ‘Nicinho’, and a sister, Joana D’Arc, or ‘Jane’.

He grew up playing for the Santos Juniors team. When he was sixteen, he moved to Portuguesa Santista where he became a professional footballer. He then began a sort of pilgrimage from one club to another, all of them small fry: Tanabi in the São Paulo region, Iturama and Frutal in the state of Minas Gerais. There, in the south-east of Brazil, Neymar Pai contracted tuberculosis. This put him out of action for a year. He decided to quit football and to go back to work as a mechanic at his father’s garage. However, he then received an offer from Jabaquara, a historic club in the metropolitan area of Baixada Santista.

His father was not enthusiastic but Neymar accepted anyway. During the week he worked as a mechanic and at weekends he played. He strung four good games together, one of which was a friendly against União Mogi. The referee for the match, Dulcídio Wanderley Boschilla, pointed him out to the managers of Mogi, who were immediately interested. At the end of the first interview, he was sent to train with the first team. At the end of the second interview with the chairman at that time, José Eduardo Cavalcanti Teixeira, or ‘Ado’, Neymar signed a contract, for one season, expiring in 1989. ‘In those days the salaries were not very high,’ Pintado recalls, ‘The sponsor was UMC, the University of Mogi. We were paid more or less 350 reais a month but it was enough to live on.’

After years of flitting from one city to another, from one changing room to another, Neymar found himself at Mogi. He was amazing on the pitch and a real success in that A3 league. He played so well that he attracted attention from other clubs in the region. Officials at Rio Branco do Americana, a club in the small city of Americana in the state of São Paulo, were impressed by Neymar when he played against their team at the old stadium in Rua Casarejos and they wanted him, whatever the price.

Despite their loss to União, Rio Branco won the title. A striker was needed to strengthen their line-up. They offered Neymar a decent amount and Neymar was about to accept. It was a one-off chance of a lifetime. União’s former treasurer Moacir Teixeira recalls, ‘He needed money for his family. He wanted to buy a house for his folks who lived in Baixada Santista.’ Neymar made his wishes completely clear to the club’s managers – who had no intention of letting him go.

‘He was our best striker; he was a great person who deserved everything he had worked for,’ says the former treasurer. So Moacir, together with nine other União fans, formed a group to match Rio Branco’s offer using their own funds. The agreement was made on 21 December 1989 with ten signatories. The group of investors bought Neymar’s registration and ensured he could continue to play for Mogi. The transaction value was 100,000 cruzados novos, 10,000 per signatory, ‘and with no interest, with no economic return,’ comments Moacir. In today’s money it would be around 55,000 reais (about €17,000).

This was a lot of money at the time! Neymar was finally able to buy a house for his mother at São Vicente and he bought himself a car: a Monza. He felt rich, but economic and financial reforms introduced as part of the Collor Plan led to him losing his savings. In the first half of 1990, he played for União; in the second half of the year, as the club was not taking part in any tournaments, he played for Coritiba, Cataduvense and Lemense. By this time, he wanted to have a family. So in 1991, at age 26, in the church of São Pedro ‘O Pescador’, in São Vicente, he married Nadine Gonçalves. They had met when she was sixteen and he was eighteen and a rising star at Portuguesa Santista.

Their first son was born at 2.15am on 5 February 1992, in Mogi das Cruzes. Nadine’s waters broke the day before and she was taken to Santa Casa de Misericordia hospital: an impressive white and pale blue building which stands out from the city streets. The birth was natural and there were no complications – mother and son were fine. The baby weighed 3.78kg, about 8lb 5oz. The new parents found out that it was a boy only when he came into the world – an ultrasound was too expensive for them.

The first doctor to look after mother and son was Luiz Carlos Bacci (now deceased), followed by Benito Klei. It was the latter who discharged them. Being a fan of the club, he knew the baby was the son of a União player, but only when reading the birth certificate years later did he realise that he helped bring the Santos star into the world. ‘At that time Neymar Jr did not have the Mohican hairstyle so it was difficult to recognise him,’ jokes the director of the department of gynaecology and obstetrics at Santa Casa. The da Silva Santos family was accompanied home by União’s physiotherapist, Atilio Suarti. Neymar O Pai had called him and asked him to come and pick them up.

But what was the name of the little baby? Both parents were unsure of what to call him. First Nadine wanted to call him Mateus; his father agreed. They used this name for a week but they were not convinced and, in the end, when Neymar Pai recorded his son’s name at the registry, he changed his mind and gave him his own name: Neymar, adding ‘Junior’. Within the family walls, he was known as ‘Juninho’.

Nadine and Neymar Pai were happy with the arrival of Neymar Junior. Valdir Peres recalls, ‘He turned up at the hotel where the club was staying in a euphoric state. He swore that his son would one day be the best Brazilian football player ever.’ This was a statement that triggered a whole host of friendly insults and snide remarks.

The da Silva Santos family lived on the fourth floor of block C of the Safira flats, number 593 of Rua Ezelino da Cunha Glória, barrio Rodeio, a middle-class residential development three kilometres from the town centre, built by a metallurgy cooperative syndicate. The pastel-coloured buildings cling to the hillside at the foot of Serra do Itapeti, where the view opens out over Mogi. Theirs was an average-sized apartment paid for by União Mogi. Today not many remember that little boy with curly hair who lived there until he was four. ‘They were a quiet, shy family who did not attract much attention,’ recalls Licianor Rodrigues, one of the da Silva Santos family’s neighbours.

One Sunday in June 1992, after a league match against Matonese, during which he scored the equaliser for União, and before starting training, Neymar Pai decided to go and see his family in São Vicente. He loaded up his car and headed off. Nadine was sitting at his side and Juninho, just four months old, was sleeping on the back seat. It was a rainy day and the tarmac was wet. The Rodovia Indio Tibiriça was a two-way road. It was the long descent down the Serra and it was always tricky and dangerous. Every few hundred metres a sign warned of fog and reduced speed limits: just 40 kilometres per hour in some places. Suddenly a car on the opposite side of the road tried to overtake and cut into the oncoming traffic. Neymar Pai swerved and tried to accelerate out of the way but he was in fifth gear and the impact was unavoidable. The other car hit Neymar’s car head on and wedged itself into the driver’s door.

Neymar Pai’s left leg ended up on the right: his pelvis and pubis were dislocated. He could not move. Distraught, he spoke to his wife and told her he was dying. The pair looked behind them and Juninho was not there. They thought that he had been thrown out of the car on impact. They thought they had lost him forever. Neymar Pai prayed for God to take his life but save Juninho. Their car was teetering on a ledge, above the river. Nadine could not get out on her side as she would have fallen into the raging torrent below. One or two cars stopped to help and Juninho was found underneath the seat, covered in blood. His parents were beside themselves with fear for their son. An ambulance took them to the nearest hospital.

When Neymar Pai was reunited with his wife and son, Nadine was fine apart from a few scratches. Juninho had a large plaster on his head – the blood had come from a small cut on his head, caused by a piece of flying glass.

Neymar Pai was not so lucky: he had a dislocated pelvis – a serious injury. He had to have an emergency operation. He spent ten days in hospital and then four months at home in bed, suspended from a machine. He was unable to play for almost a year and had to undergo treatment, rehabilitation and physiotherapy with the help of Atilio Suarti and União masseur Antonio Guazzelli. This had been a serious accident, and it affected the rest of Neymar Pai’s career. He was not able to regain his touch. However, he did not stop playing. This was his life, his livelihood.

On 31 May 1995 he donned the famous red União Mogi centre forward shirt for a friendly exhibition match. The match was being staged to celebrate the reopening of Nogueirão. The opposition was Santos Futebol Clube, who played in the Divisão Especial (today League A1), whereas Mogi were in Intermediaria (today League A2). At Santos there were players like Toninho Cerezo and Jamelli. Mogi were coached by Valdir Peres and boasted players such as goalkeeper Haroldo Lamounier and Ricardo.

The match put Edson Cholbi Nascimento, or Edinho – Pelé’s son – and Neymar da Silva Santos, father of the future Neymar Jr, up against each other. On the one hand, a boy who had listened to the advice of his father on how to behave in life; on the other, a father who was to give to his son (as he continues to do to this day) advice on how to become a great footballer and on how to choose the right career path. Edinho, a goalkeeper, was 25 years old and was playing a routine match. Neymar Pai was 30 and will always remember the match, because it was a match against Santos and he was asked to take the free kicks. Edinho saved his attempts with ease: Neymar bodged them all. A shame. Mogi wanted to win but against professional players it was not possible. The match ended in a draw: 1–1. One goal for Jamelli of Santos and one for Gilson da Silva of Mogi. A good result in any case. The reopening event carried on according to plan.

One year later, on 11 March 1996, the da Silva Santos family welcomed a new member: Rafaela was born.

After many happy years playing for União, Neymar decided to embark on a new adventure. He went back to his parents’ house in São Vicente in barrio Nautica 3 for a time, and started to look for a new contract. This time he ended up at Operário of Várzea Grande, Mato Grosso.

The chairman of the club, Maninho de Barros, saw Neymar Pai play for Batel de Paraná. He was looking to strengthen his team. He did not know the name of the footballer who was playing such an excellent match, even scoring a goal. At half time, he asked Laurinho, a striker for Batel, who he was and at the end of the match he met up with Neymar Pai and offered him a transfer to Várzea Grande.

Neymar wanted to think about it, and to discuss it with his family. It was only after speaking to an executive at Operário and learning that he could move his family there that Neymar Pai accepted the offer. He was to wear the tricolour shirt of Várzea Grande.

His opening match was the semi-final of the state tournament and the hopes of the chairman were realised: Neymar scored and provided the final pass for another goal in the 4–1 win against Cacerense. In the final, Operário faced União de Rondonópolis. In the first leg, away from home, Neymar did not play and the match ended in a draw. In the return leg on 3 August 1997, Neymar Pai played and the match ended 2–1.

For Operário it was a twelfth Mato Grosso league title. For Neymar da Silva Santos it was the only league title of his career, a career which ended in 1997 at the ripe old age of 32. He felt old: since the accident, his body had not responded as he wanted it to; the pain during matches and training began to hit home. The continuous transfers began to weigh on him and his family. The contracts were less lucrative and he had no hope of achieving anything else in his profession. He headed home to start a new life with plenty of surprises in store.

Chapter 3

São Vicente

Cups, trophies, medals of all types, shapes and sizes from various sports: the display cabinets of the Clube de Regatas Tumiaru are full of souvenirs of past titles spanning its 108-year history.

It started with the aim of ‘bringing young people together via sport and in particular water sports’. The club’s first premises were on the waterfront in São Vicente, right next to the historic port of Tumiaru from which it gets its name. Today the clubhouse is located at number 167 in what is known locally as ‘post office square’ but officially is Praça Coronel Lopes. The black and white two-storey building bears the club’s coat of arms: two crossed oars, a lifebuoy and the date 1905. We are in the centre of São Vicente, the first city founded by the Portuguese in South America, on 22 January 1532.

São Vicente is a municipality of the small region of Santos and shares the island with the neighbouring city. It is known for its tourism and its trade, attracting hoards of visitors. Of note is the monument celebrating 500 years of Brazil, designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer: a white platform on the top of Ilha Porcha, which provides an incredible view of the coast. It is not to be missed.

The guided tour of Clube Tumiaru is also worthwhile – the city centre site, that is, not the site on the waterfront. There is an open-air swimming pool, training rooms, a gymnasium for capoeira, dance, tai chi chuan, judo and gymnastics, and the futebol de salão hall. The hall is enormous, with semi-circular vaults, large windows which light the hall, stands to the side, and wooden parquet floor ruined by years of matches. The hall is empty, as it is early morning. Training and lessons take place in the afternoon. Here on this pitch, at age six, Neymar Jr began to play football for a club.

A bola (the ball) has always been his love, his object of desire. His uncontainable passion for the ball is so strong that in May 2012 he stated, ‘a bola is like the most jealous woman in the world. If you do not treat her well, she will not love you and she can even hurt you. I love her to bits.’

He has shown this passion right from when he was a young boy. His mother, Nadine, remembers one time at the market when she was buying potatoes. He was only two years old at the time and ‘Juninho’ risked his life crossing the road to chase after a little yellow plastic ball. And just like Neymar has said a thousand times, Nadine remembers that he used to sleep with a ball. After only a few years, Neymar had collected no fewer than 54 balls in his room. It was not Neymar’s room; more like the balls’ room. The room was so full of balls that Neymar had to scrunch himself up in the corner of the bed. A bola was even in the photos of his childhood. In one photo of him, taken when he was just a young boy, he is wearing the Santos shirt and under his arm he is carrying a black and white patched ball.

Neymar Pai was amazed that when Juninho was only three years old, instead of grabbing the ball with his hands and shouting, ‘It’s mine’, he gave it back with his feet. For him, football was important, something serious; he had what Brazilians call jeto; that is, aptitude, talent. In his grandparents’ house in barrio Nautica 3, father, mother and kids all slept in the same room. Between the mattress, the wardrobe and the chest, there was very little space but Juninho made the most of this tiny corridor by playing football. The mattress was perfect for training as a goalkeeper: blocks, dives and saves on the line. When he was tired, he could always use his sister and cousin Jennifer as goalposts while he practised free kicks and penalties.

And yet when Neymar Jr first makes his mark, it is not with the ball at his feet. Roberto Antônio dos Santos, aka Betinho, passionately tells the story of the first time he saw Neymar Junior: ‘It was the end of 1998 and I was watching a match on Itararé beach in São Vicente. Tumiaru were playing Recanto de la Villa. I was concerned for my son, I looked around to check where he had gone and a little boy, as thin as a rake, with short hair and stick-like legs, caught my eye. He was running up and down the stands which they had installed for the event. He ran effortlessly, as though he was running on the flat, as though there were no obstacles in his way. He ran without stopping for one second. His fitness, his agility and his coordination made an impression on me. It was something rare for a tiny young boy. This made a difference to me. A light came on in my head. I asked a friend, “Who is that boy?” He told me that it was son of Neymar Pai who was playing in the match for Recanto and had just missed a penalty. I looked at the father: he was well built and had good ball control. I looked at Nadine, who was attending the match: she was tall and thin. I immediately began to think about the genetics of Neymar Jr’s parents: they were two fine biological specimens. This made me wonder how the little’un would play football.’

This was the discovery of the star about whom everyone is talking.

Fifty-six years old, with a laugh that regularly breaks up his discourse, Betinho is a former right-winger at amateur level. Born in São Vicente, Betinho works in Santos’s youth set-up and travels all over Brazil, indeed all over the world, looking for new talent. In 1990, Betinho discovered Robson de Souza, aka Robinho, in Beira Mar, a futsal club in São Vicente. Robinho now wears number 7 for AC Milan.

In his office on the second floor of Vila Belmiro, Santos FC’s stadium, Betinho does not hold back from telling me about the young Neymar Jr: ‘At that time, I was coaching Clube de Regatas Tumiaru. I was putting together a team of young kids born in 1991 and 1992 to play in the São Vicente league. At the end of the match, I went to speak to his father to see if he would let me take Neymar Jr to Tumiaru for a trial. Neymar Pai accepted and the boy came with me. The first time I saw him touch a ball, my heart started beating like mad. I saw the footballing genius that he could become. I realised that lightning had struck twice in the same place. First Robinho and now another rare pearl, both in São Vicente. You find footballing talent where kids are most in need. And in São Vicente there are lots of people who come from poor regions. Families who cannot afford to live in Santos because it is too expensive. Here there is a gold mine of talent.’

It is almost impossible to get a word in edgeways with Betinho. But I want to understand how he worked out, from just a glance at Neymar Jr running up and down the stands, that he could be good at football. Betinho’s answer is inspirational: ‘God gave me the talent to see players who can make the difference and are one step ahead of the rest.’

It is worth noting that by the time he discovered Neymar, Betinho had already been working as a talent scout for five to six years – something which, together with divine intervention and the undoubtedly talented kids of Mogi Da Cruzes, helped him to choose.

But what were Juninho’s talents at that young age? ‘Football was something which came from the inside for Neymar Jr. At six years old he already had his own style. He was fast and poised, he had great imagination with the ball and could make something out of nothing. He loved dribbling, he knew how to kick the ball and was not afraid of taking players on. He was different to the others, you could have put him with 200 kids his age and he would have stood out just the same.’

Betinho gets up to explain a fundamental concept, starting with music, in particular the samba. ‘When I used to put samba music on, I would see him move, gyrate, dance as he did when he had the ball at his feet.’ Despite being a little bit overweight, Roberto Antônio dos Santos demonstrates a few steps to explain that without this movement of the hips and legs, you cannot become a great Brazilian footballer. He continues, ‘Neymar at that time did the ginga movement.’

Ginga is the fundamental movement of capoeira, the Brazilian martial art introduced to the country by African slaves, which combines combat, dance, music and corporeal expression. Ginga is a coordinated movement of both the arms and the legs which prevents an attacker from having a fixed target, thus tricking him and making him attack so that the capoeirista can then counterattack. The word stands for movement of the body that can represent sensuality, malice, skill or dexterity. The etymology of the word could be the ancient French jangler, which derives from the Latin joculari, meaning ‘joke, pretend and have fun’.

Leaving etymology to one side, ginga is something magical; something Brazilians have in their blood from birth: a gift, an innate talent for movement, for dance, for football, for shimmying, for dummying opponents on the football field. It is the spirit and identity of Brazilian football. And this quality is one that Juninho had in spades at only six years old, according to his talent scout.

Betinho continues: ‘What was lacking was strength and stamina, something which is completely normal for a kid at that age. He needed to refine and improve on his skills, his technique, by playing in a team but without losing his passion for dribbling the ball.’

Betinho gave his body and soul to make sure Juninho’s skills developed. He took him to play in a futsal tournament in Jabaquara, a nearby town. The team won the trophy. Neymar Jr was the leading goalscorer and the best player of the competition. Betinho also took the young Neymar with him to teams where he coached: Portuguesa, Gremetal and a second spell at Portuguesa.

With curly hair and a few milk teeth missing, and wearing the white shirt with sky blue trim and the coat of arms with the crossed oars on the chest, Neymar started to make a difference on the coloured parquet salão pitch. (The game of futebol de salão, or futsal, where small-sided teams play on indoor courts with a smaller than usual ball, was invented in 1933 in Montevideo by Professor Juan Carlos Ceriani Gravier, who wanted to get his students playing football in a small gymnasium.) He wore number 7, and his Clube de Regatas club membership card, no. 1419, had a serious-looking photo of the young star.

Betinho’s hopes were realised. He knew that he had a pearl in his grasp. He continues, ‘Neymar was different: he was a very intelligent player. He thought quickly, his mind saw things before the others did. He was always one step ahead. He knew where the ball would end up and how his opponent would react. He took on board my advice and that of the other coaches. He then metabolised the advice and put it into practice. He was the first to arrive at training and the last to leave the pitch. He loved playing with the ball. I cast my mind back to Robinho at the same age and Neymar seemed more talented. I said so to his father: “You have a son who can be one of the greatest footballers. He will be at least as good as Robinho.”’

Neymar Pai, who never got to the top of his profession, believed him and had complete faith in him – though naturally he continued to monitor his son’s progress.

Betinho comments, ‘Both Neymar’s mother and father were close to him: they always followed what he was doing. They treated him with great affection and love. Even if the finances of the family were not the best, they always did what they could for their son. They educated him to be honest, sincere – you know, a good boy.’

But what was he like when he was six years old?

‘He was a happy little boy, always cheery, always smiling. He had a nice way about him. He was good at school and he liked studying. He got on well with adults and classmates alike. He was friends with everyone and a born leader. His mates trusted him because of what he did on the pitch. I am very proud of the fact that I was the first coach of a player that is now known all over the world.’

Betinho shows me photos of him with the star, including one Neymar Jr put on Instagram after a match. He also shows me a white Santos shirt with a dedication: ‘To my first coach with love from your friend and athlete Neymar Junior.’

That the young man now wears the number 11 shirt for Barcelona is thanks to Betinho and his eagle eyes; his having seen Neymar’s potential and opened the doors to the world of football. In turn, Betinho is indebted to Neymar Jr and his family for their loyalty and decency: ‘In 2002 when Santos tried to coax Juninho away from the team but without me, Neymar Pai did not accept. He said, “My son needs Betinho at the moment.” When Santos tried again and managed to agree a contract, Neymar Pai required that I went to Santos with Neymar Junior. I have Neymar Pai to thank for my job.’ Betinho laughs when telling this story.

When asked how he sees his pupil now, Betinho answers, ‘As of 2009 when he started playing for Santos’s first team, Neymar has been miraculous. He has matured. He has refined his skills. In a few years, he has won individual and team titles. This is the experience he has taken with him to Barcelona.’

But will playing with Messi, Iniesta and Xavi influence his game? ‘When Pelé played for the Brazilian team which won the 1970 World Cup, he played with Rivelino, Tostão and Jarzinho. Neymar is a star playing with other stars. I hope that he will soon be the best in the world. Yes, I am sure, Neymar will be better than Messi and after having given so much joy to my country, he will give joy to the entire world.’

Chapter 4

Praia Grande

He cleans his hands with a rag, straightens his hair, then looks straight ahead and, indicating the adjacent construction site, says, ‘That there is the best goal Neymar has scored.’ Gilberto Leal is a mechanic on the outskirts of Praia Grande. His used tyre shop is right in front of a white wall. On the large tin gate hangs a sign:

Dados informativos da obra. Cesionario: Instituto Projecto Neymar Junior. Local: Jardim Gloria Quadra 27 A y 27 B. Tipo de Obra: Costrução da Centro Social y Esportivo.

(Information about the works. Contractor: Neymar Junior Project Institute. Location: The Garden Gloria Quadra 27 A and 27 B. Type of Work: Sports and Social Centre.)

An employee with a white helmet and blue overalls opens the doors of the workshop to visitors who want to find out a bit more. It is lunchtime: builders and workmen are eating under a makeshift canopy. Two HGVs loaded with concrete pillars and a crane dominate the area which was once a football field, that of Gremio. It is here that the Neymar Institute will be opened in 2014, spread over 8,400 square metres running along the length of the Avenida Ministro Marcos Freire. It is a sports complex with a football pitch, swimming pool, gym, multi-sports hall, auditorium and refectory. The stated aim is to ‘contribute to socially disadvantaged families’ socio-educational development through sport’. During the first phase it will have capacity for 300 kids aged between seven and fourteen, from poor backgrounds with a per capita income of R$140. In phase two, it is expected that the institute will help 10,000 people of various ages. Gilberto comments, ‘It is a good idea. Let’s hope that it brings many good things to this area. Jardim Gloria is not a favela but almost. Life here is not easy, especially for young kids.’

This verdict is confirmed by two social workers: juvenile delinquency, street crime and lack of prospects are the problems facing the area of Praia Grande, a town with 29,000 inhabitants, twenty minutes’ drive from Santos. It is a real problem zone.

On 18 January 2013, the plan for the Institute was presented at the Palacio Das Artes in the town. Neymar Pai and Neymar Jr were on the stage, together with the local councillor who was hosting. ‘Juninho’ stated that he was very happy with the project: ‘[We are happy] to be building a space for kids and for the inhabitants of Jardim Gloria. We do not want to discover a new star but rather help families realise a dream and help young kids develop and make plans for their lives. I hope the Institute can serve as an example.’

Neymar Jr is happy to be setting up this place, a place that he would have liked to have experienced when he was kid but no such place existed. He is happy to give back to the people of the area what he and his family got from them. He is happy to do something for the place where he grew up and where he spent most of his childhood. He commented, ‘I played on the streets here with my friends: I had great fun in the endless marbles matches; here I played with my kite.’

Neymar Jr moved here from São Vicente with his family when he was seven years old and he lived here until he was fourteen. They lived at number 374 Rua B, Jardim Gloria: