Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

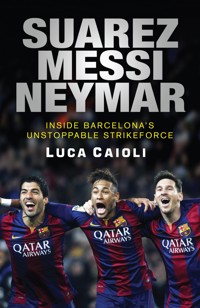

Barcelona has long been regarded as a home of beautiful football. In July 2014, already boasting Lionel Messi and Neymar, Barça added Luis Suárez to complete a forward line that was undeniably special, even by their own high standards. They had taken greatly differing paths from South America to the starting line-up at the Nou Camp. Messi joined Barcelona aged just thirteen, Neymar served a spectacular apprenticeship in Brazil and Suárez enjoyed spells with Ajax and Liverpool – three prestigious educations with an emphasis on attractive play. Through exclusive testimonies from friends, families, managers and teammates, acclaimed football writer Luca Caioli documents their individual journeys and examines the phenomenal success of Barça's 'MSN' years to date, including the 2015/16 league and cup double.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 203

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SUÁREZ MESSI NEYMAR

About the author

Luca Caioli is the bestselling author of the biographies Messi, Ronaldo, Neymar, Suárez and Balotelli, all published by Icon Books. A renowned Italian sports journalist, he lives in Spain.

SUÁREZ MESSI NEYMAR

INSIDE BARCELONA’S UNSTOPPABLE STRIKEFORCE

LUCA CAIOLI

First published in the UK and USA in 2014

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Reprinted with revisions 2016

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Grantham Book Services,

Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa

by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed in Canada by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300

Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

Distributed in the USA

by Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

ISBN: 978-190685-086-9

Text copyright © 2014, 2016 Luca Caioli

Translation copyright © 2014, 2016 Sheli Rodney

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in New Baskerville by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

Introduction

1 The scouts

2 Football: a passion since childhood

3 Family

4 Clubs

5 National team

6 High points

7 Low points

8 Neymar’s arrival

9 World Cup

10 Secrets of success

11 Suárez’s arrival: early days

12 MSN

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Suárez, Messi and Neymar … 9, 10 and 11 … FC Barcelona’s lucky numbers. They are widely considered to be the most powerful strike force in the world, the holy trinity that have taken Barça to incredible heights in the short time they have played together. What’s more, the club that has dominated the last decade of European football is now betting on an entirely South American trio. Meanwhile, eternal rival Real Madrid has taken the polar opposite approach with an equally magnificent formation of three players born and trained in Europe: Portuguese Cristiano Ronaldo, Frenchman Karim Benzema and Welshman Gareth Bale.

Of course, Leo Messi is homegrown. Barça is his first and only team, at least for now. Back in his hometown in Argentina he played briefly for Newell’s Old Boys in the youth leagues, but he moved over to join Barcelona’s youth academy while he was still a boy. He has come up through the ranks of La Masia, and he knows the playing style, what the club represents, its aspirations. But he has also inherited the Latin American culture of playground and street football and all its traditions. It’s a ‘bilingual’ background that can only benefit his relationship with his two teammates.

Messi has played with Neymar for three seasons and Suárez for two, and the understanding between the three of them is evidently better than ever. In fact, it is extremely unusual for the Flea to have found such symbiosis with other strikers. There were others before Ney and Lucho (as Luis is known), such as Samuel Eto’o, David Villa and Zlatan Ibrahimović, but they all ended up leaving Barça. Now, however, they are on a roll, which is not always easy to achieve in a sport as competitive as football. ‘Let’s not kid ourselves, it’s surprising that they get on so well. And that’s the key to things running so smoothly. If they didn’t have that relationship, Barça wouldn’t have won everything it’s won, and things wouldn’t be like this now,’ explains former Blaugrana captain Carles Puyol in an interview with Barça TV. ‘We don’t pay attention to the statistics, we’re just enjoying the moment,’ adds Suárez. ‘We have a great relationship on and off the pitch. We’re not performing for anyone else, it all comes from inside. We just enjoy ourselves.’ And Barça central midfielder Ivan Rakitić agrees: ‘Although they have very different personalities, they are in perfect harmony on the pitch. It sounds over the top, but I’m telling you, Messi, Suárez and Neymar are the best friends in the whole world, possibly the best in the history of football.’

For Neymar it was more difficult to integrate into the Barça ranks than it was for Luis. On top of that, his performance on the pitch was quickly eclipsed by the controversy surrounding his signing and his legal problems. And it was his first experience of European football, so it was only natural there would be a period of adjustment. For his part, Lucho was hounded by headlines following his biting incident involving Italy’s Giorgio Chiellini during the Brazil World Cup, an act that earned him an eight-match suspension from international football and a four-month ban.

Suárez apologised publicly prior to his move to Barcelona, but after the deal was announced there were mutterings that the Uruguayan would not be a good fit for the Catalan team’s values. Whatever his flaws, there is no denying his abilities, which have made him one of Uruguay’s top players – and one of the best paid. Since the move, Luis has once again demonstrated his versatility and capacity to adapt. This is one of his greatest strengths, which made him an indispensable player in all of his former teams: Montevideo’s Nacional, Groningen, Ajax and Liverpool. He is well versed in historic clubs and demanding competitions such as the Premier League – enriching experiences that have enabled him to integrate at Barça, and particularly with Leo and Ney.

The three players have very different physiques and abilities. Suárez represents strength, Neymar is technically skilful, while Messi, as the winner of five Ballon d’Ors, has it all. A trio of aces that can champion a second golden age for Barça, like that of the Guardiola years. The statistics speak for themselves: 130 goals between them across all competitions in the 2015–16 season. They are all natural goal-scorers, used to winning prizes and breaking one record after another. It’s incredible considering Luis and Lionel are only 29, and Neymar is just 24. They have all enjoyed immense success so far, so it will be interesting to follow their progress over the next few years with the Blaugrana (‘Blue and Clarets’, as Barça are known in Catalan).

Their triumphs on the pitch have also made them genuine idols, global icons on the level of rock stars or Hollywood actors, followed by millions. They stir up a frenzy both on and off the pitch and their faces and shirts are among the biggest sellers worldwide. Everything they do is heavily scrutinised and their personal lives are the subject of as much fascination as their sporting achievements – fuelled further every time they post a picture of themselves with their partners or children on one of their various social media pages. They are more than just sportsmen: they are wizards with the ball, but they are also extremely bankable public figures across every conceivable market. They are 21st-century footballers – as successful commercially as they are on the pitch.

This is the tale of three kids who knew from an early age that they wanted to be the best, and stopped at nothing to achieve their goals. There are surprising similarities in their parallel stories, which have now finally converged. Here we recount their childhood, family life, first brush with football, club successes, national careers, and key moments of triumph and pain. The chapters that follow offer an insight into three exceptional sportsmen – fierce, tireless warriors. Numbers 9, 10 and 11, the three magic numbers, the three stars of FC Barcelona.

Chapter 1

The scouts

Luis Suárez, Leo Messi and Neymar Júnior almost certainly wouldn’t be global football stars if not for the people who discovered them. Or at least, the road to success would have been significantly longer. Because it’s not enough just to have great skills. Becoming a football star is as much about being lucky enough to get noticed – having someone recognise your potential even while you’re still a youngster playing a childhood game. Here we pay tribute to the three people who ‘discovered’ the three Barça forwards.

* * *

El Cabeza or Cabezón – ‘Big Head’, as Suárez’s friends and family call him – owes a lot to his paternal uncle, Sergio ‘El Chango’ Suárez. He was the one who taught him how to kick a ball at four years of age, when Luis was the Deportivo Artigas mascot. El Chango lived in a modest, low-rise house in Salto, in Barrio Cerro. Despite the rundown nature of the area, the locals took pride in their surroundings.

El Chango is shy. He works as a carpenter, but he previously played for amateur Uruguayan teams Deportivo, Fénix and Colombia – a couple of which are now defunct. When asked what Luis was like back then, his uncle smiles. ‘He was just like he is now. Football was everything to him. He woke up with a football and went to bed with one.’ He paints a picture of a strong player with a constant desire to improve. ‘At first Luis was a bit awkward with the ball, but he committed to every shot. He never left a play unfinished. He wanted to win. He wanted to score, he wanted to be the goal-scorer, whatever it took. Just as he does now.’

Is it really possible that one of the most prolific strikers in Premier League history was so clumsy as a child? ‘He was better in defence, so much so that when we played against tough opponents, I put him in goal,’ admits Sergio. ‘He didn’t like that but he did his best. He saved the day on many occasions.’

It is difficult to imagine Barcelona’s latest star signing as a goalie, but El Chango has proof in the form of a plastic bag bulging with mementos. With a smile just like his nephew’s, the greying, bespectacled uncle flips through the photos. There is the Deportivo Artigas kids’ team with Luis in front of goal, there are photos of the kids lined up with arms folded and serious expressions, staring into the lens – just like adult players do before a big match. They are wearing red with white and blue stripes and light blue shorts. ‘The strip is pretty much the same as that of Independiente Argentino,’ notes Sergio. It’s hard to spot Luis. ‘You should recognise him here,’ he says, pointing out a dark, scruffy-haired kid with a cheeky smile They are lined up in order of height at the edge of the tufty grass pitch. Sergio is also visible – considerably younger, with dark brown hair, busy lining them up. Luis is third along with shorts that are too big for him, holding back a smile.

Another picture shows Luis in goal, with a haircut reminiscent of the Beatles. This time he’s in an orange strip, standing in the second row with his hands behind his back, right next to his uncle who is trying to get a kid in front of him to stop fidgeting. The trip down memory lane brings back plenty of memories. One of the best is when, ‘in the middle of a match, Luis raised his hand and asked the referee to stop play so he could go to the toilet. Another one is when he was five years old. He was playing when he saw his brother, Paolo, in the crowd, eating a piping hot pizza. Luis kicked the ball into touch and ran to Paolo to get a slice. Paolo told him to get back on the pitch but Luis was having none of it. Luis was yelling, he wanted the pizza. Typical boyish antics. Luis was a good kid, just like he is now.’

Luis has always acknowledged that it was his uncle who taught him to kick a ball, but El Chango is reluctant to take any credit: ‘I didn’t teach him anything. He already had the basics. What he has achieved is all down to him.’

It’s a very different picture from the one painted by Braian Rodríguez, a striker with Chilean first division club Everton de Viña del Mar, who also played at Deportivo Artigas as a kid. ‘El Chango taught us to love football and to live it with passion. This was important advice which, as a kid, stays with you for the rest of your life. He taught us how to move on the pitch and caress the ball. He explained how to kick, tackle, free yourself from markers and finish off a move. He taught us that football is a team game and that there is no point playing for yourself, that passing is key. All of these things are counterintuitive when you are a kid. He was a great teacher. Without his help, we may not have made it to where we are today.’

* * *

Leo Messi may not have made it to the top if the late Salvador Ricardo Aparicio hadn’t believed in him when he was just a boy. Aparicio spent his whole life working on the railways. As a youngster he wore the number 4 shirt for Club Fortín and, more than 30 years ago, he coached children on Grandoli’s pitch. ‘I needed one more to complete the team of children born in 1986. I was waiting for the final player with the shirt in my hands while the others were warming up. But he didn’t show up, and there was this little kid kicking the ball against the stands,’ recalled Don Apa – as he was affectionately known in Leo’s hometown of Rosario – whenever anyone asked him how he discovered the Blaugrana star. ‘The cogs were turning and I said to myself, damn … I don’t know if he knows how to play but … So I went to speak to the boy’s grandmother, who was really into football, and I said to her: “Lend him to me.” She wanted to see him on the pitch. She had asked me many times to let him try out. On many occasions she would tell me about all the little guy’s talents. The mother, or the aunt, I can’t remember which, didn’t want him to play: “He’s so small, the others are all huge.” To reassure her I told her: I’ll stand him over here, and if they attack him I’ll stop the game and take him off.” Well … I gave him the shirt and he put it on. The first ball came his way, he looked at it and … nothing.’ Why? ‘He’s left-footed, that’s why he didn’t get to the ball.’ He goes on: ‘The second it came to his left foot, he latched onto it, and went past one guy, then another and another. I was yelling at him: “Kick it, kick it.” He was terrified someone would hurt him but he kept going and going.’ Leo’s first coach couldn’t recall whether he scored the goal, but what he did remember was that he had never seen anything like it. ‘That one’s never coming off,’ he said to himself. And he never took him off.

Like El Chango, Aparicio also kept a bag full of precious memories from the old days. His favourite was a photo of a green pitch, a team of kids wearing red shirts and, standing just in front of a rather younger-looking Don Apa, the smallest of them all – the white trousers almost reaching his armpits, the shirt too large, the expression very serious, bowlegged. It’s Leo. He looks like a little bird, like a flea, as his brother Rodrigo used to call him.

‘He was born in ’87 and he played with the ’86 team. He was the smallest in stature and the youngest, but he really stood out. And they punished him hard, but he was a distinctive player, with supernatural talent. He was born knowing how to play. When we would go to a game, people would pile in to see him. When he got the ball he destroyed it. He was unbelievable, they couldn’t stop him. He scored four or five goals a game. He scored one, against the Club de Amanecer, which was the kind you see in adverts. I remember it well: he went past everyone, including the keeper. What was his playing style? The same as it is now – free. What was he like? He was a serious kid, he always stayed quietly by his grandmother’s side. He never complained. If they hurt him he would cry sometimes but he would get up and keep running. That’s why I argue with everyone, I defend him, when they say that he’s too much of a soloist, or that he’s nothing special, or that he’s greedy,’ the coach said after Lionel became a global star.

The first time Leo came home from Spain, Don Apa went to visit him. He never forgot that particular reunion. ‘When they saw me it was madness,’ he used to say. ‘I went in the morning and when I returned it was one o’clock the next morning. We spent the whole time chatting about what football was like over there in Spain.’ On another occasion, when the neighbourhood organised a party in Lionel’s honour, the old maestro didn’t get to see his former pupil as Leo wasn’t able to make it. He called later to apologise, with a promise to see him next time. Señor Aparicio was never bitter about it – on the contrary, he always spoke with much affection about the little boy he coached all those years ago. He even cried watching him on TV as he scored his first goal in a Barça shirt. His daughter, who was in the other room, asked: ‘What’s wrong dad?’ ‘Nothing,’ he said, ‘it’s emotional.’

* * *

Roberto Antônio ‘Betinho’ dos Santos’s story is rather different to the other two: discovering Neymar Júnior changed his life. ‘In 2002 when Santos tried to coax Neymar Júnior away from the team but without me, Neymar Pai did not accept. He said, “My son needs Betinho at the moment.” When Santos tried again and managed to agree a contract, Neymar Pai insisted that I went to Santos with Neymar Júnior. I have Neymar Pai to thank for my job,’ he recalls with a smile. The São Vicente native and former amateur right winger still travels the length and breadth of Brazil – and the world – in search of new talent. He has always had a good eye for spotting a diamond in the rough. In 1990 he saw São Vicente five-aside club Beira-Mar and discovered Robson de Souza, aka Robinho, the former Real Madrid, Manchester City and AC Milan forward who is now on loan to Santos.

But the Neymar story is particularly exceptional. ‘It was the end of 1998 and I was watching a match on Itararé beach in São Vicente. I was distracted by my son – I turned round to see where he had got to, and I noticed a tiny kid, with short hair and skinny legs. He was running up and down the makeshift stands they had put up for the event. He was running with total ease, as though he were running on a completely flat surface, no obstacles. That’s what stood out for me. It was like a light bulb moment.’ At the end of the match the scout asked the father’s permission to let him try out at Tumiaru. Neymar Pai agreed. ‘The first time I saw him touch a ball, my heart started beating like mad,’ recalls Betinho. ‘I saw the footballing genius that he could become.’

But what were Neymar’s talents at that young age? ‘Football was an innate ability for him. He already had his own style, even at six years of age. He had speed and balance and he invented imaginative tricks of his own. He loved to dribble, he knew how to shoot and he wasn’t afraid of his opponents. He was different from the others, you could put him in the midst of 200 other kids his age, and even then he would shine.’ Betinho continues: ‘What was lacking was strength and stamina, which is completely normal for a kid at that age. He needed to refine and improve his skills and technique, by playing in a team but without losing his passion for dribbling.’

Betinho took ‘Juninho’ – as Neymar’s family call him – with him to teams where he coached: Portuguesa, Gremetal and a second spell at Portuguesa. ‘Neymar was different: he was a very intelligent player. He thought quickly, his mind saw things before the others did. He was always one step ahead. He knew where the ball would end up and how his opponent would react. He took on board my advice and that of the other coaches, and put it into practice. He was the first to arrive at training and the last to leave the pitch. He loved playing with the ball.’

But what sort of six-year-old was he? ‘He was a happy little boy, always cheery, always smiling. He had a nice way about him. He was good at school and he liked studying. He got on well with adults and classmates alike. He was friends with everyone and a born leader. His mates trusted him because of what he could do on the pitch. I am very proud of the fact that I was the first coach of a player that is now known all over the world.’

Chapter 2

Football: a passion since childhood

Why do you love football so much?

‘I don’t know. I first took a liking to it as a child, as all children do, and I still enjoy it a lot. For me, playing ball is one of the most beautiful things in the world.’

It’s true, football has been Leo Messi’s greatest love since he was a little boy – although it wasn’t his first. At three years old, Leo prefers picture cards and much smaller balls – marbles. He wins multitudes of them from his playmates and his bag is always full. At nursery or at school there is always time to play with round objects. Then, for his fourth birthday, his parents give him a white ball with red diamonds, and it is then, perhaps, that the fatal attraction begins. One day he surprises everyone. His father and brothers are playing in the street and Leo decides to join the game for the first time. On many other occasions he had preferred to keep winning marbles – but not this time. ‘We were stunned when we saw what he could do,’ says his father, Jorge Messi. ‘He had never played before.’

From that moment on, he and his football are inseparable. ‘He was a typically shy child and he talked very little. He only stood out when he played ball. I remember that at break time in the school playground the captains who had to pick the teams always ended up arguing because they all wanted Leo, because he scored so many goals. With him they were sure to win. Football has always been his passion. He often used to miss birthday parties in order to go to a match or a practice,’ recalls his childhood friend Cintia Arellano. And when asked today how he gained such confidence and learned so many tricks, the Flea replies: ‘By spending every moment with a football. When I was little I would stand all on my own on a corner and kick the ball around continuously.’