11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Forum

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

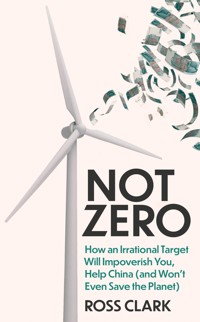

'Bravely challenging the Establishment consensus … forensically argued' - Mail on Sunday The British government has embarked on an ambitious and legally-binding climate change target: reduce the country's greenhouse gas emissions to Net Zero by 2050. The Net Zero policy was subject to almost no parliamentary or public scrutiny, and is universally approved by our political class. But what will its consequences be? Ross Clark argues that it is a terrible mistake, an impractical hostage to fortune which will have massive downsides. Achieving the target is predicated on the rapid development of technologies that are either non-existent, highly speculative or untested. Clark shows that efforts to achieve the target will inevitably result in a huge hit to living standards, which will clobber the poorest hardest, and gift a massive geopolitical advantage to hostile superpowers such as China and Russia. The unrealistic and rigid timetable it imposes could also result in our committing to technologies which turn out to be ineffective, all while distracting ourselves from the far more important objective of adaptation. This hard-hitting polemic provides a timely critique of a potentially devastating political consensus which could hobble Britain's economy, cost billions and not even be effective.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Not Zero

How an Irrational Target Will Impoverish You, Help China (and Won’t Even Save the Planet)

ROSS CLARK

Contents

Preface

The morning of 21 July 2023 delivered a political surprise in Britain. It wasn’t that the Conservative Party had heavily lost two by-elections held the day before – the government was deeply unpopular for a variety of reasons, and voters have long been using by-elections in order to record a protest against a sitting government. The shock was that the Conservatives had failed to lose the third by-election held on the same day. Voters in Uxbridge and South Ruislip – the seat of the former Prime Minister Boris Johnson – had narrowly elected the Conservative candidate.

The reason for the non-defeat seemed clear. Voters who might otherwise have protested against the Conservative government had chosen instead to protest against the decision of the Labour Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, to extend his ultra-low emission zone (ULEZ) to outer London. It meant that anyone with a petrol car which failed to conform to Euro 4 emissions level (in practice most cars more than 15 years old) or a diesel car which failed to reach Euro 6 emissions level (most cars more than seven years old) would have to pay a daily charge of £12.50 to drive their car anywhere in London’s 32 boroughs. Some of the poorest motorists who relied on cars or vans to get about (such as nurses, carers on night shifts, or tradespeople who need to carry around a lot of kit) would be hit. And no, few plumbers were impressed by the suggestion of shadow cabinet minister viiiDavid Lammy that they might care to take the tube to work with their toolboxes, U-bends, blowtorches and all.

The by-election result confirmed a point which had been made in the hardback edition of this book, published in February 2023: that while the public is happy to support green policies in general and net zero policies in particular, support tends to die away very quickly when people are presented with specific policies which threaten to hit them personally, either through extra taxes or charges or through restrictions on their freedom. While ULEZ is not strictly about carbon emissions – the Euro regulations on which it is based cover nitrogen dioxide and particulate emissions from engines – it was a clear marker that politicians cannot take support for green issues for granted.

Yet the reaction to ULEZ seemed to catch both the Labour and Conservative parties by surprise. That Parliament was imposing an open-ended bill on the UK public did not seem to occur to the MPs who, in 2019, nodded through a target for the UK to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, although a growing number of MPs are now daring to question the wisdom of making this legally binding commitment. The two main parties have simply assumed that people were so concerned about climate change that they would accept virtually any measure that was introduced to tackle it. They have been working on the assumption either that untested technologies will automatically fall into place to allow life in net zero Britain to continue as before, minus the carbon emissions – or that the public will willingly pay the costs to replace gas boilers with heat pumps, swap petrol cars for electric ones, as well as travel less and curtail their leisure activities.

The summer of 2023 proved to be something of a watershed in the debate over net zero – not just in Britain but elsewhere. While the weather in Europe and North America ixprovided ample opportunities for those out to exaggerate the effects of climate change, with footage of every heatwave, wildfire and storm tweeted out by an eager body of activists, economic reality has begun to bite. Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has forced a rethink of energy policy across Europe. Coal mines have been reopened, facilities to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) hurriedly assembled. While no country that has made a commitment to net zero has yet formally gone back on it, there has been a modest retreat in the more controversial policies. The European Union relaxed a previous decision to ban petrol and diesel cars by 2035 and decided that cars powered by internal combustion engines would still be allowed after that date so long as they could run on synthetic fuels (given that you can make synthetic fuels to any recipe you like it means an effective stay of execution for all petrol and diesel cars).

In Britain, the Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, travelled to Aberdeen in July 2023 to announce that the government would grant over a hundred new licences for oil and gas extraction in the North Sea. Previously, the government had been happy to allow the industry to run down, in the belief that the future lay in renewable energy. Fossil fuels would still be supplying a quarter of the country’s energy even after 2050, Sunak suggested – with Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) used to mop up carbon emissions. The government department which handled energy matters was renamed the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, marking a sharp change in emphasis.

In September 2023 Sunak announced that some deadlines would be relaxed. The date for banning sales of new petrol and diesel cars was put back from 2030 to 2035, and sales of new oil and gas boilers can continue until the same date. Homeowners will no longer be put under pressure to upgrade their homes to an Energy Performance Certificate rating of xC or above – something which could cost tens of thousands of pounds in many cases.

It is not the end for Britain’s legally binding net zero target; in August 2023 Sunak ruled out dropping it or holding a referendum on the subject. Nevertheless, an air of realism has begun to creep into the debate, if not among Sunak’s critics, many of whom are within his own party. The year 2050 is still sufficiently far off – it lies beyond the expected careers of those currently in government – that the serious practical problems presented by the target do not yet loom as large as they will come to do in the coming years.

The debate has moved on in several ways since the first edition of this book was completed in November 2022. It has become clearer that the sharp downward trend in the price of renewable energy has, for now, come to a halt. In the summer of 2022 it became fashionable to quote an assertion by the website Carbon Brief that wind energy was ‘nine times cheaper’ than gas-powered electricity. As explained later on, this was never a realistic figure – it was based on comparing the long-term guaranteed prices offered to the owners of wind farms with the ‘day-ahead’ prices which have to be paid to the owners of gas-fired power stations to persuade them to fire them up for a few hours when wind and solar energy are scarce. What has changed since 2022, though, is that wind farm companies are no longer prepared to accept the low prices that they were then. The ‘nine times’ claim was made on the back of an auction won by Swedish wind farm operator Vattenfall, which agreed to supply electricity from its proposed Boreas wind farm in the North Sea for the equivalent of £37.35 per MWh at 2012 prices (now closer to £45 per MWh). But in July 2023 the company pulled the plug on the project saying that it was no longer viable to supply power at that price thanks to a 40 percent surge in the cost of constructing a wind farm.1 Advocates of renewables, such xias Labour’s climate change secretary Ed Miliband, who a year earlier had been championing the apparent low cost of wind energy, sharply changed tack and complained that the sector is not sufficiently subsidised.

It becomes increasingly hard to see how Britain, or any other country which has made such a commitment, can reach net zero by 2050. Targets are already slipping. According to WindEurope, a trade body for the wind industry, orders for new turbines across Europe fell by 47 percent in 2022 compared with 2021, as higher installation costs ate into future revenues.2 Electric car sales have settled at around one sixth of the UK market, and with subsidies and tax advantages being withdrawn it is becoming clear that electric cars are not going to sell themselves on the back of their virtues – if the technology does not improve to bring prices down they will have to be forced on the public. The government is struggling to give away vouchers for new heat pumps. Under its Boiler Upgrade Scheme £450 million worth of £5,000 grants – i.e. a total of 90,000 – have been made available to fund heat pump installations between 2022 and 2023. But by June 2023, already 13 months into the scheme, only 19,000 applications had been made.3

None of these technologies, it needs to be emphasised, take us to net zero in themselves. To achieve that, the government will have to find carbon-neutral ways of storing large quantities of intermittent energy, the manufacture of electric vehicles must be decarbonised, steel, plastics and all, and the electricity to power the heat pumps must also be fully decarbonised. Persuading people to switch to these devices is merely the first stage in a long process of decarbonising those sectors.

Meanwhile, there is little sign of the boom in ‘green jobs’ that we were promised as a result of the net zero commitment – not in Europe at least. On the contrary, green jobs are draining away from Britain and the rest of Europe to China xiiand the United States. China, reports the Global Wind Energy Council, now accounts for 60 percent of the global wind turbine market, a share which it is growing at the expense of European manufacturers.4 How come? Chinese-made turbines are cheaper partly as a result of lower energy costs there – more than half of which is generated by filthy coal. The quest for clean energy in Britain, in other words, is helping to boost coal consumption, and therefore carbon emissions, in China. Yet those Chinese emissions don’t count towards Britain’s carbon budget, which includes only emissions physically spewed out in Britain. That needs to be borne in mind when government ministers try to claim that emissions have fallen by nearly half since 1990.

In any case, the rate at which emissions are falling has begun to slow as we pick off the low-hanging fruit – in particular the replacement of coal-fired power stations with a mixture of wind, solar and gas. In March 2023 the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero reported that UK emissions had fallen by 2.2 percent in 2022 compared with 2021. But much of this was down to mild weather (and high energy prices) dissuading homeowners from turning on the heating – emissions from the heating of buildings fell by 16 percent. Strip away the effect of mild weather and the government conceded that greenhouse gas emissions had actually risen by 0.7 percent on a like-for-like basis.5 It is going to be a very tricky road ahead if we are really to eliminate net emissions by 2050.

But is anyone else going to come with us? The world’s two biggest emitters, China and the United States, still show no interest in following Britain and the handful of other countries which have set legally binding targets to reach net zero by 2050. They may have aspirations, but not targets written into law which will cause them problems of the kind that Britain is already facing. While Britain and other European countries xiiimake the sacrifices, the United States and China are quite brazen about their aim to reap the profits. President Biden has used climate change as an excuse to instigate a new age of protectionism – handing out grants and tax incentives through his Inflation Reduction Act to people and businesses who buy American-made green products such as electric cars. Since 2022 this has blown up into a diplomatic row between the US and the EU. British and other European manufacturers wanting to export cars to the United States now have to bear high energy costs thanks to net zero; they now also have to compete in a market in which US manufacturers are subsidised.

UK businesses are already being lured across the Atlantic by the handouts. In May 2023, Tevva, an Essex-based company developing battery- and hydrogen-powered lorries, reported that it had received multiple approaches from government officials across the United States trying to entice it with offers of grants and tax breaks – and was minded to take up one of the offers.6 The Inflation Reduction Act is unlikely to do the United States much good in the long run – it is horrendously expensive for US taxpayers and is likely to provoke a trade war which will harm the country in other ways. But it isn’t doing Britain or other European countries much good either. Far from being united on a journey to net zero, as our political leaders are wont to say, climate change is being ruthlessly exploited to promote and protect US industry – while we shackle ours with net zero regulations, taxes and levies.

One development since the first edition of this book went to press is the issue of climate reparations – the idea that Britain and other countries that were early to industrialise owe compensation to developing countries which are said to be suffering the effects of man-made climate change. It is an idea promoted, for example, by Ed Miliband who while avoiding the term ‘reparations’ told the BBC in November 2022 that Britain should be paying ‘loss and damage’ to countries such xivas Pakistan, which had suffered serious flooding three months earlier. Actually, Britain already pays substantial sums in aid to Pakistan: £200 million in development aid in 2020 and £26 million in emergency aid after the August 2022 floods. But there are two problems with holding an early industrial country like Britain financially responsible for recent flooding. Firstly, Britain is rapidly slipping down the chart of countries ranked by cumulative historical carbon emissions. At 78.5 billion tonnes it is already well behind China (249 billion tonnes),7 one of the developing countries that has suggested it is owed reparations. The whole concept of climate reparations makes no allowance for the massive good that has been done through industrialisation – which has transformed the lives of almost everyone on Earth.

Secondly, the link between global warming and extreme weather events is a lot less clear-cut than is often made out. The evidence that carbon emissions are responsible for worsening the 2022 Pakistan floods would certainly struggle to stand up in court. In September 2022 the Guardian, among other news outlets, reported that climate change had made the floods ‘up to 50% worse’. This was based on a study by the group World Weather Attribution, which seeks to calculate the role of climate change in extreme weather events by comparing what has actually happened with what climate models predict would have happened in a world that was 1.2 degrees Celsius cooler. But the study itself did not have the certainties used in the headlines. It concluded, in the case of rainfall totals for the worst five days of the monsoon period, that ‘some of these models suggest climate change could have increased the rainfall intensity up to 50%’. Dig a little deeper, and you see that the models were all over the place – and some even predicted that rainfall totals would have been greater in cooler world. While one model suggested climate change had increased rainfall intensity by 56 percent, another suggested xvthat it had reduced it by 21 percent.8 As we shall see later, that is the reality with extreme weather and global warming – the evidence is weak and often points in contrary directions. And far from all observed changes in the climate are negative. In some ways, the trends are beneficial.

None of this means that we shouldn’t act to reduce carbon emissions, and this book does not argue against that. There are very good reasons why we should be concerned about the extra carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases which have been pumped into the atmosphere, and why we should seek to cut, and eventually eliminate, emissions. But the legally binding commitment to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 made by Britain and some other countries is a hostage to fortune that was made without proper regard to the costs and practicalities. It promises to cause financial hardship and to thwart economic growth. That is the case made in this book – and one which has grown only stronger in the year since the first edition was published.

September 2023

Notes

1 Rachel Millard, ‘Blow to UK renewable plans after Vattenfall halts wind farm project’, Financial Times, 20 July 2023.

2 ‘Investments in wind energy are down – Europe must get market design and green industrial policy right’, WindEurope press release, 31 January 2023, windeurope.org/newsroom/press-releases/investments-in-wind-energy-are-down-europe-must-get-market-design-and-green-industrial-policy-right/.

3 ‘Boiler Upgrade Scheme statistics: June 2023’, Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, 27 July 2023, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/boiler-upgrade-scheme-statistics-june-2023.

4 Yasuki Okamoto, ‘Chinese manufacturers dominate wind power, taking 60% of global market’, Nikkei Asia, 19 August 2023, asia.nikkei.com/Business/Energy/Chinese-manufacturers-dominate-wind-power-taking-60-of-global-market.

52022 UK Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Provisional Figures, Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, 30 March 2023. Available at assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1147372/2022_Provisional_emissions_statistics_report.pdf.

6 ‘The Inflation Reduction Act is turning heads among British businesses’, Economist, 16 May 2023.

7ourworldindata.org.

8 ‘Climate change likely increased extreme monsoon rainfall, flooding highly vulnerable communities in Pakistan’, World Weather Attribution, 14 September 2022, www. worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-likely-increased-extreme-monsoon-rainfall-flooding-highly-vulnerable-communities-in-pakistan/.

1.

The conference of idle promises

It begins, like a Victorian melodrama, with a train, lashed by a Halloween storm, pulling to a halt in the English countryside. As the minutes turn to hours – a fallen tree has blocked the line – the increasingly restive passengers begin to converse, in this case via Twitter, and realise they are not random individuals; they are there for a reason. They are all travelling to the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow where the UK government, which is hosting the event, will try to convince the world to follow its unilateral example and legally commit to reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050. And they begin to see their predicament through that prism. The global ambassador for a development charity opines that British public transport infrastructure is in a dire state. The President of the Federation of Austrian Industries is regretting that, having flown in to Heathrow from Mexico in the morning, he hadn’t done as many of his fellow delegates had done and taken an onward jet to Glasgow.

But a storm is no longer allowed simply to be a storm; rather it is a portent of global doom. It is Jon Snow, the anchor on Channel 4 News, who catches the mood of the train as he tweets: ‘En route to COP26 – trees and branches affected by climate change have slowed our rail journey – tho the branches have been cleared we are down to 5mph – What an irony! What a message! We MUST change! Dare we hope that we shall?’2

The Earth is warming and there have been observed changes in the climate, and in sea levels, which pose problems for human societies. But to blame the storm that brought down the power lines on climate change is directly at odds with observational evidence presented in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment report – seen by many as the bible of climate science – published in August 2021. That cited evidence that the wind speeds over land throughout the northern hemisphere have been falling in recent decades. Moreover, the number of intense storms – those with a central pressure of lower than 960 millibars – in the North Atlantic have fallen sharply since 1990.1 In other words, if climate change is having any effect on your chances of a rail journey in Britain disrupted by high winds it is to reduce them. Not to mention that the reason trees fall on railway lines in Britain more than they used to is that since the end of the steam train era, trees and bushes beside railway lines have been allowed to grow up in order to help with biodiversity. Network Rail even promotes the estimated 6 million trees which line railways in Britain as having a role in ‘much-needed carbon capture’2 – too bad if falling branches delay your train.

But these are details which get lost in the climatic hyperbole which surrounds the COP26 summit. The growing divide between the statements of campaigners who claim to have science on their side and what scientific data actually says goes unnoticed. In COP26 land it is accepted wisdom that mankind, along with the planet, is on the brink, and only drastic action will save us – no matter what the cost to society and to ordinary people. The summit’s opening presentation quickly attains the air of an evangelical rally, with world leaders – many of whom having flown in hours earlier on gas-guzzling private jets, emitting between five and 14 times as much carbon as they would have done had they flown by commercial plane33– trying to outdo each other in their doom-laden addresses. The then UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson – who, six years earlier, wrote that the ‘fear’ of man-made climate change was ‘without foundation’ – expresses the zealotry of the convert by telling delegates that the world is now ‘a minute from midnight’. The UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, announces that we are all ‘digging our own graves’ by failing to cut carbon emissions. Documentary-maker David Attenborough declares that humans ‘are already in trouble’. The Prince of Wales, whom Johnson later calls a ‘prophet’, demands a ‘vast, military-style campaign’ to defeat climate change. But it is the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, who outdoes everyone else by stating that failing to address climate change would ‘allow a genocide on an infinitely greater scale’ than the Holocaust – a comment for which he later apologises.

It gradually becomes clear, once the Archbishop has left his pulpit, that not everyone in the congregation quite shares the same devotion to the cause. US President Joe Biden arrives in a cavalcade of 21 vehicles from Edinburgh airport, and then appears to fall asleep in the conference chamber – surely the most carbon-intensive afternoon nap in history. Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping haven’t bothered to come at all – the latter an especial disappointment given that his country accounts for 33 percent of the world’s carbon emissions.4 As for Putin, he recorded a video message for the forestry and land use conference part of COP26, but that was all.

A few promises and pledges are wrung out of world leaders. Xi Jinping has already said that his country will try to become carbon neutral by 2060, a full decade after the UN would like – and, unlike Britain’s commitment to reach net zero, it isn’t written into law. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi says his country will attempt to eliminate net carbon emissions 4by ten years later, in 2070 – but he wants huge sums of Western money in return for his pledges. A deal is cobbled together in the hope of decreasing the rate of deforestation in some countries – although within two days Indonesia has already begun to pour cold water on the deal by saying that it will not allow the deforestation deal to get in the way of development; in other words it will continue to chop down trees where that is required to create new oil palm plantations and the like. Seventy-seven countries sign a pledge to phase out coal power by 2030 (in the case of developed countries) or by 2040 (in the case of developing ones). But even then many countries only sign because of the caveat ‘or as soon as possible thereafter’. Joe Biden – worshipped by progressives who see him as the antithesis of the isolationist Donald Trump – is expected to be among those who sign. Then, a day beforehand, his Democratic party loses the governorship of the state of Virginia – which has a big coal-mining industry – and Biden wobbles, declining to sign.

The final pact commits no country to do anything by any particular date. It is a mish-mash concocted to offer something to everyone. It takes care to include, for example, the phrase ‘climate justice’, which has been wafted around on placards outside the hall by activists. Yet the pact places no legal commitment on any countries to phase out the burning of fossil fuels (although Britain and a few other countries have placed that commitment on themselves). India and China successfully object to a clause which mentions ‘accelerating efforts to phase out unabated coal power’, so that the words ‘phase out’ are replaced with ‘phase down’ – whatever that means. As India points out, the communiqué says nothing about phasing out oil and gas, so why should countries with coal reserves suffer? Britain and other wealthy nations, on the other hand, agree to a clause regretting that they haven’t yet stumped up the £100 billion of cash they have promised 5to pay poorer countries to help them cope with a transition away from fossil fuel, and demanding that they double this promised sum. That, and the reference to ‘climate justice’, makes it clear what is coming: there are going to be multiple demands for cash from any country which fancies it – and it is going to come out of the pockets of taxpayers in wealthy countries. Any country with high historical carbon emissions – and Britain, as the seat of the industrial revolution, is top of the list – is going to be on the hook.

Where does this fit with climate science? That concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have increased since the mass burning of fossil fuels is beyond doubt. So, too, is the warming trend in global temperatures over the past century and a half – which, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), has seen global temperatures rise by an average of between 0.8 and 1.3 degrees Celsius. How much of the latter is caused by the former is something we can never know for sure, but the conclusion of the IPCC that ‘it is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land’ is not unreasonable. That it would be better if we weren’t changing the composition of the atmosphere is something on which we ought all be able to agree. The world has a strong incentive to reduce, even eventually eliminate, emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet the political campaign for net zero has gone way beyond what climate science can stand. It has become a world where every climatic extreme, every piece of adverse weather, is blamed on human influence and is a portent of an even more doom-laden future to come. Hence a heatwave in July 2022, which set a new high-temperature record in Britain and sparked wildfires in the Gironde department of south-western France, becomes a ‘heat apocalypse’ in the words of a French meteorologist.5 A Norfolk garden which suffered a fire in the 6heat became a scene ‘like Armageddon’.6 We are told by an 8-year-old climate activist that ‘the planet is dying’,7 that 320 million people face starvation by 2030.8

The constant use of such language and assertion helps us neither understand climate change nor come up with a reasoned policy on what to do about it. It is just silly, emotional language, with news organisations, politicians, state officials and campaigners trying to outdo each other in the extremeness of their language. We hear constantly, too, of how climate change is supposedly causing devastating floods, storms, tornados and even freezing spells. In contrast to rising temperatures, for which we have good data, the claim that climate change is bringing us other kinds of extreme and undesirable weather is somewhat less supported by data. On the contrary, as we shall see later on, in some cases data points in the opposite direction to the lazy claims being made.

There are two wings to the net zero movement. The first argues that the only route to salvation is for us all to reduce our living standards, to abandon consumerism or even to do away with capitalism for good. This is the wing represented at its extreme end by Extinction Rebellion and other protest groups. The second argues that technology will save us without us having to make great sacrifices – indeed, it often asserts that far from costing us, the net zero target will end up enriching us by unleashing a rush of wealth-creating innovation that otherwise would not have taken place. The market, somehow, will provide. This is broadly the position of Britain’s Conservative government.

Both these wings have lost touch with reality. The first, because it overstates climate science and because it fails to grasp that people – the poor especially – are not going to accept being made poorer. Going vegan, or giving up the car commute for a morning cycle ride might be pleasant-enough options for the well-off, but the poor are not going to be 7prepared to shiver or go hungry in the name of cutting carbon emissions. And they really would shiver and go hungry. If you want to reach net zero over the next few years through the curtailment of lifestyles you are not going to achieve it without returning society to a pre-industrial level of subsistence.

But the second school of thought is equally naive in expecting technology magically to allow us to achieve net zero emissions without any reduction in our living standards. The industrial revolution of the 18th century, and all subsequent advances which have transformed human societies, have been based on one thing above all others: a source of cheap, concentrated energy – whether that be coal, oil or nuclear. To expect the same level of wealth in an economy based on far less dense forms of energy, such as wind and solar – which appears to be the current expectation of the UK government and other European governments – is not realistic. To expect to be able to achieve net zero without a serious cost to the economy is no more than Panglossian optimism. It would require multiple forms of new technology which either have not yet been invented or which have yet to be proven on a commercial scale. And it would require all this to be achieved in less than 30 years’ time.

Whenever you make these points, however, they tend to be batted away with the generalised assertion – without any evidence to support it – that ‘the costs of acting are much less than the costs of not acting’ (if, indeed, you are not dismissed as a ‘denier’). The prospects of future climate change are so grim, we are told, that failing to commit to net zero by 2050, or some date very soon after that, is simply not an option.

Really? Throughout COP26 we keep hearing about ‘the science’ – a supposed set of truths which cannot be challenged. But it is remarkable how few actual climate scientists are delivering the lectures at COP26; those who undertook the 8painstaking studies which went into the IPCC report published three months earlier, and whose work points to some interesting, some conflicting changes in the climate but hardly to cataclysm, seem mysteriously absent. Climate change is a world that has come to be controlled by activists and campaigners who claim to be on the side of science and reason but who are really spinning narratives which suit ulterior motives.

By the end of COP26 it becomes painfully clear that there is a schism between mostly European countries, which, in keeping with the fiery rhetoric of many from the podium, have resolved to eliminate their carbon emissions at any cost, and those like Russia, China and the United States, which have signalled very clearly that while they will try to reduce emissions they will not compromise economic growth in order to do so. While plenty have made promises and expressed aspirations, Britain remains one of the very few countries to have tied itself down with a legally binding commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Glasgow is the confirmation of a political alignment which has been in the making for several years but which now becomes visible with even more clarity. It is no longer West versus East, North versus South, but the committed players in the fight against climate change and the less committed players. They are playing a very, very different game, with very different consequences for their citizens.

239Notes

1 Natalia Tilinina et al., ‘Comparing cyclone life cycle characteristics and their interannual variability in different reanalyses’, Journal of Climate 26:17, 2021, 6419–38, doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00777.1.

2Biodiversity Action Plan, Network Rail, 2020. Available at www.networkrail.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Network-Rail-Biodiversity-Action-Plan.pdf.

3 ‘Private jets: Can the super-rich supercharge zero-emission aviation?’, Transport & Environment, 27 May 2021, www.transportenvironment.org/discover/private-jets-can-the-super-rich-supercharge-zero-emission-aviation.

4 ‘Global CO2 emissions rebounded to their highest level in history in 2021’, International Energy Agency (IEA) press release, 8 March 2022, www.iea.org/news/global-co2-emissions-rebounded-to-their-highest-level-in-history-in-2021.

5 Daniel Keane, ‘“Heat apocalypse” warning in France as wildfires spread’, Evening Standard, 18 July 2022, www.standard.co.uk/news/world/europe-heatwave-heat-apocalypse-warning-france-wildfires-b1013103.html.

6 ‘UK heatwave: Wildfire left garden like Armageddon – Norfolk renters’, BBC News, 20 July 2022, www.bbc.com/news/av/uk-62244872.240

7 Sunil Kataria and Mayank Bhardwaj, ‘“Planet is dying”, India’s 8-year-old climate crusader warns’, Reuters, 28 September 2020, www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-youth-india-idUSKBN26J0ZH.

8 Ilona Amos, ‘COP26: Climate change will see 320 million people worldwide facing starvation this decade, report warns’, Scotsman, 8 November 2021, www.scotsman.com/news/environment/cop26-climate-change-will-see-320-million-people-worldwide-facing-starvation-this-decade-report-warns-3449974.

2.

Self-sacrifice

In May 2019 Theresa May, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, was on her way out, her short and unhappy time in office nearly at an end. Her three-year premiership had been dominated by Brexit – Britain’s departure from the European Union – for which the British public had, shockingly to some, voted in 2016. Some blamed May for failing to secure a trade deal, or even a withdrawal deal, with the EU. Others saw her as the victim of her own MPs, who had been unable to agree on any of the possible deals that she had put before the House of Commons. By now her position was untenable, and a leadership election to choose a successor as Conservative Party leader and Prime Minister was underway.

On her way out of the door, however, she planted a very large bomb to be detonated beneath her successors. Amid the drama and chaos of Brexit, it was hardly even noticed by the British public. Yet it had far greater implications – and potentially far more destructive power – than even the matter of Britain’s departure from the EU. The bomb had the seemingly innocuous name ‘Climate Change Act (2050 Target Amendment) Order 2019’. It wasn’t even a new Parliamentary act, rather a small amendment to one which had been passed eleven years earlier, the Climate Change Act 2008. Whereas the original act had legally committed Britain to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent (relative to 1990 levels) by 2050, the new amendment demanded that net emissions 10be reduced to net zero by this date – with any lingering emissions compensated for by measures to remove carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

The change was nodded through by the House of Commons without even a vote. In the hour and a half allotted for debate only one MP expressed reservations – Labour backbencher Graham Stringer, one of the few members of the House of Commons with scientific qualifications, asked why the government had not produced an ‘impact assessment’ as it does with most pieces of legislation and was told by a government minister that it wasn’t necessary. Two days later the House of Lords – the upper house of the UK Parliament – did hold a vote and passed an amendment complaining that the government had ‘given little detail of how the emissions target will be met’ and that it had ‘made a substantial change in policy without the full and proper scrutiny that such a change deserves’. But the Lords didn’t actually oppose the net zero target – they voted for it in spite of complaining the government had failed to show any indication as to how it could be reached. And thus, with hardly a whimper, a piece of legislation with huge implications for UK citizens and UK industries became law.

Net zero. It sounded a noble objective. As Chris Skidmore, the government minister who introduced the bill to the House of Commons, observed, it would mean Britain becoming the first major economy in the world to make a legally binding commitment to eliminate greenhouse emissions. But what did it really mean, what was it going to cost, and did any of the MPs who had just nodded it through actually understand the implications?

The government’s case was based around a claim made some months earlier by the Climate Change Committee (CCC) – which advises the government on climate policy – that achieving net zero emissions by 2050 would cost 11between 1 and 2 percent of GDP per annum by 2050 – roughly equating to an eventual bill of £1 trillion by that date. But this, said the minister, was before you took into account the many benefits, such as increased air quality and what he called ‘green-collar jobs’. Moreover, he implied that falling costs would reduce the bill further. Forget the bill, in other words; it will be a modest fee given what we will gain.

Not one MP pointed out the folly: how can you possibly estimate the cost of doing something when you have no idea how it can be done? By 2019, Britain was well on its way to phasing out coal power and generating around 15 percent of its electricity from wind farms and solar farms. A small proportion of electric cars were already on the road. But fossil fuel-free aviation? Decarbonisation of the steel and cement industries? Satisfying an enormous hike in demand for power as cars and domestic heating were switched from oil and gas to electricity? Energy storage to cope with the intermittent nature of wind and solar energy? These were among the many technological problems with which the country had hardly begun to grapple. While in some cases solutions might exist in theory or have been demonstrated on a laboratory-scale, no one knew whether they could successfully be scaled up and at what cost. As John Kerry, the US climate envoy, was later to say, half the technology which will be required to achieve net zero has yet to be invented.1 The UK Parliament, however, had just approved a law obligating the country to net zero with no idea of how, when or whether that technology would be developed – and not the faintest idea of what it would really cost.

When National Grid ESO – the company which runs the electricity grid in Britain – attempted to calculate its own estimate of the cost of reaching net zero by 2050 it came up with an answer dramatically different to that of the CCC. In 2020 it presented four different scenarios of how Britain might 12attempt the transition, involving different blends of renewable energy, changes in consumer behaviour and so on. Its estimated costings in each case came out at around £160 billion a year of investment, eventually reaching a total of around £3 trillion.2 That was three times the figure which the CCC had touted just a year earlier – and National Grid was only trying to price up the decarbonisation of the energy sector, not agriculture and difficult-to-decarbonise sectors such as steel and cement. To MPs who had treated the CCC’s figure as gospel, and nodded through the 2050 target, it was a sharp reminder that they had committed the country to an open-ended bill, the eventual size of which no one could reasonably guess – other than to say it was going to be huge. Those MPs knew full well the government’s lousy record on estimating costs of things we do know how to do – such as building a high-speed railway in the shape of HS2 from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds, whose estimated costs nearly trebled from £37.5 billion in 2009 to £107 billion in 2019.3 Yet they had swallowed whole an attempt to put a price on doing something which had vastly more unknowns and which involved technologies yet to be invented or proved on a commercial scale.

It took two years for the government itself to come up with some kind of plan of how it would reach net zero. Britain could do it ‘without so much as a hair shirt in sight’, wrote Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the foreword to his Net Zero Strategy, published in October 2021. ‘No one will be required to rip out their existing boiler or scrap their current car.’ By 2035, the document went on to say, the UK would be powered entirely by clean electricity ‘subject to security of supply’. To this end it was going to invest in floating wind farms and, by 2024, make a decision as to how to fund a large nuclear plant (yes, just one, and it was only the decision that would be made by 2024; it would take another decade or so 13to build). There would be investment in hydrogen, so that hopefully by 2035 we might have a public hydrogen supply to replace the gas supply (although a decision on whether to pursue this was delayed until 2026). Also by 2035, the price of electric heat pumps might have come down – might – to make them a practical replacement for new gas boilers which would by then be banned. New petrol and diesel cars would be banned from 2030, hybrids from 2035. There would be £750 million of investment to plant new woodlands and restore peat bogs.

But the Net Zero Strategy left more questions unanswered than it answered. How are we to establish security of electricity supply if we come to rely even more on intermittent renewables? How is one nuclear power station going to solve our problems when it – along with the one currently under construction at Hinkley in Somerset – won’t even replace Britain’s seven existing nuclear power stations, all of which are due to reach the end of their working lives by 2035? Does the government really have confidence that it will turn out to be economical to produce hydrogen by zero-carbon means – as opposed to manufacturing it from coal and gas, as almost all the world’s hydrogen is currently produced? You can order us all to buy electric cars, but how are you going to make sure that the cars are themselves zero carbon, given that a hefty proportion of a vehicle’s lifetime’s emissions are tied up in its manufacture? If we are going to cover the countryside with woodland, where does that leave food production? Are we going to be even more reliant on importing it from overseas, with the consequence that our food might end up with a higher carbon footprint than now?

On top of that was left dangling the biggest question of all: what is it all going to cost us, and who is going to end up paying the bill? On the same day that the Net Zero Strategy was published, the Treasury produced its own assessment of 14the costs of net zero. Did the Treasury agree with the Climate Change Committee’s assessment that it would cost no more than £1 trillion, or National Grid’s estimate of £3 trillion for the energy sector alone? It couldn’t say. It offered no estimate of the cost of net zero, arguing, rather, that it wasn’t possible to make such an estimate at this stage. As for who will pay, that was at least becoming clear. We were all going to be paying, either through our taxes or through supplements on our energy bills.

Britain, in short, is to embark on an experiment unique in human history, in which it voluntarily rejects whole areas of established technology which currently make society and the economy function, and tries to replace them with novel technologies, some of which do not currently exist and others of which may exist on a demonstration level but have not yet been scaled up. And the whole project has to be completed in just 27 years, no allowances, no wriggle room. It will be an industrial revolution to put all previous periods of human progress in the shade – if it can be achieved. But there is a very, very big and expensive ‘if’ there. It is generally good to be ambitious and optimistic. There is a point, however, at which it becomes foolishness.

Is there even a Plan B in case technology disappoints and it proves not possible to decarbonise Britain without causing huge damage to the economy? I asked the business secretary, Kwasi Kwarteng, this in October 2021 and he denied there was a need for such a plan. No minister seems brave enough to say that the 2050 target may have to be revisited. Asked in July 2022 whether they were committed to the 2050 target, all five remaining Conservative leadership candidates confirmed that they were – although one, Kemi Badenoch, had previously suggested the target might have to be moved out to 2060 or 2070.4 All objection to the Net Zero Strategy has been brushed aside by government ministers who insist there really is no 15alternative: so dire is the climate emergency that we simply have to decarbonise everything we do – fail to do so and we will be lashed by ever more dramatic weather: tossed, boiled, frozen and drowned. Behind it, though, lies a Little Englander fantasy: that somehow we can tackle climate change on our own, even if other countries do not follow our example. Yet Britain accounts for less than 1 percent of global emissions (or a bit more if you count them on a consumption basis rather than emissions basis, as we shall see later).

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, China, which accounts for 33 percent of global emissions, is addressing climate change in its own way – one which isn’t going to put constraints on its industries or involve the impoverishment of its people. And many other countries are adopting the same attitude.

Notes

1The Andrew Marr Show, BBC, 16 May 2021.

22020 Future Energy Scenarios: Costing the Energy Sector, National Grid ESO, November 2020.

3 ‘High Speed 2 costs’, Institute for Government, 29 January 2020.

4 Christopher McKeon, ‘All Tory leadership candidates confirm commitment to net zero’, Evening Standard, 18 July 2022, www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/kemi-badenoch-caroline-lucas-alok-sharma-liz-truss-prime-minister-b1013144.html.

3.

Meanwhile, in China

The COP26 conference was preceded by a number of incidents of adverse weather over the summer of 2021 which increasingly came to be blamed on man-made climate change. A heatwave in British Columbia, floods in the Rhineland, wildfires in California and Turkey; all were depicted as signs of a growing climate emergency which was taking even climate scientists by surprise with its ferocity.

Or at least they were in the West. World Weather Attribution, a joint project by Imperial College London, the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and others, published a study which at first sight appeared to blame the Rhineland floods fairly and squarely on man-made climate change. Rainfall of the intensity which had occurred on the two days before the Rhineland floods, media reports confidently stated, was now up to nine times as likely to occur as it was in the mid-19th century, when the world was 1.2 degrees Celsius cooler than it is now. Anyone who bothered to read the paper itself would have reached a somewhat different conclusion. The modelling used in the study had produced such a wide spread of results – it suggested that the risk of such rainfall had increased by between 1.2 and 9 times – as to be meaningless. The scientists indeed admitted that their analysis ‘pushes the limits of what current methods of extreme event attribution are designed for’.1 Moreover, the study only assessed the risk of the rainfall experienced 17on the two days immediately prior to the floods. Yet, as was admitted, a large factor behind the floods was the state of the ground prior to those two days – it was saturated after weeks of above-average rain. In fact, climate models have tended to predict drier summers for the Rhineland,2 suggesting that the peculiar set of circumstances which preceded the floods of July 2021 might be less likely to occur in a warmer world.

This did not stop the summer’s floods from becoming a rallying cry for COP26, with Alok Sharma, the president of the event, describing flooding in the UK as a ‘sober reminder’ of why the world desperately needed to cut carbon emissions. Surveying the damage in the Rhineland, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said: ‘We have to hurry, we have to get faster in the fight against climate change.’

In China, however, a very different attitude prevailed. The week following the Rhineland floods saw serious floods in the Henan province of central China. In the city of Zhengzhou, several passengers were drowned on metro trains. Across the region as a whole, 302 people were reported to have died.3 Coming hot on the heels of the German floods, Western media were quick to attribute the disaster to climate change. It was widely reported to have been the heaviest rain in a thousand years – a claim which seems to have emanated from the meteorological station at Zhengzhou but which stands at odds with the meteorological record. Although there is some evidence that heavy precipitation is increasing in China, the deluge of 2021 was far from unprecedented; worse had occurred in living memory. In July 2021 Zhengzhou recorded 24 inches of rain over three days. Yet at Linzhuang, close to the Banqiao Dam 100 miles to the south, 1,605 mm of rain (63 inches) was recorded over the same period in 1975 when Typhoon Nina struck; 830 mm (33 inches) fell in a single six-hour period. On that occasion, 26,000 people were killed directly by the flood, 10 million people were left homeless 18and a further 100,000 deaths were attributed to the famine and disease which followed.4

In contrast to Western media, in China there was little attempt to blame the 2021 deluge on climate change. Ren Guoyu of China’s National Climate Centre was reported to have ‘dismissed the connection between heavy rain in Zhengzhou and global climate change’ and instead blamed it on ‘abnormal planetary scale atmospheric circulation’ – weather, in other words.5

Climate change has not gone unrecognised by the Chinese government. For the past decade the China Meteorological Administration Association has published a ‘Blue Book’ giving its own assessment of climate change, which closely matches that of the IPCC (the IPCC report itself that is, not the reporting of it). The 2020 edition, for example, declares that average global temperatures have risen by 1.1 degrees Celsius ‘since preindustrial times’. As far as rainfall is concerned, it notes that ‘heavy precipitation events’ increased in China between 1961 and 2019.6

Nor is China absent from efforts to decarbonise its economy. While continuing to build new coal plants the country is a heavy investor in renewable energy. Indeed, it is the world leader. In 2021, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, it had 282 GW of installed capacity of wind power, along with 254 GW of solar. The next country on the list, the United States, had 118 GW of wind power and 76 GW of solar.7

In September 2020, addressing the UN via video, Chinese President Xi Jinping had a surprising announcement to make. Having previously avoided committing his country to reach net zero carbon emissions, he was now suggesting that China would reach this goal by 2060: ‘Guided by the vision of building a community with a shared future for mankind, China will continue to make extraordinary efforts to scale up its nationally determined contributions. China 19will adopt even more forceful policies and measures, and strive to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060, thus making greater efforts and contributions toward meeting the objectives of the Paris Agreement.’