Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

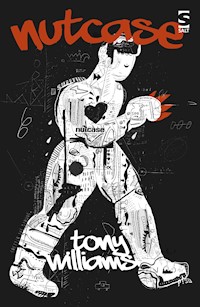

Aidan Wilson's misfortune is to be hard as nails In this darkly hilarious and seriously horrifying book Williams tells the story of Aidan, a vigilante and young offender from one of Sheffield's roughest estates. At breakneck speed, we see Aidan's world unravel as he goes from hero to outlaw, fighting against all-comers and the circumstances he can't escape. But is he a victim or architect of his own demise? A brutal and breathtaking account of living with violence in the English city. There are lots of crime novels, but Nutcase is something different: a novel about crime which isn't interested in the conventions of crime fiction. The novel is based on a specific Icelandic saga: the Saga of Grettir the Strong. Nutcase explores the lives of people who live with violence on a day-to-day basis – how it shapes and distorts their lives, and ultimately becomes part of the normality that they live with.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

NUTCASE

by

TONY WILLIAMS

Aidan Wilson’s misfortune is to be hard as nails

In this darkly hilarious and seriously horrifying book Williams tells the story of Aidan, a vigilante and young offender from one of Sheffield’s roughest estates.

At breakneck speed, we see Aidan’s world unravel as he goes from hero to outlaw, fighting against all-comers and the circumstances he can’t escape. But is he a victim or architect of his own demise?

A brutal and breathtaking account of living with violence in the English city.

There are lots of crime novels, but Nutcase is something different: a novel about crime which isn’t interested in the conventions of crime fiction. The novel is based on a specific Icelandic saga: the Saga of Grettir the Strong.

Nutcase explores the lives of people who live with violence on a day-to-day basis – how it shapes and distorts their lives, and ultimately becomes part of the normality that they live with.

PRAISE FOR PREVIOUS WORK

‘These tiny fragile stories are stuffed to the brim with wit and energy and love. Their architecture is perfect, as if a thousand complex worlds had been painted onto a grain of rice. If you’re like me you’ll want to read them over and over to unearth their secrets and find out why they leave such a long and lovely aftertaste.’ —David Gaffney

‘Tony Williams has successfully used the medium of literature to weave in and out of the life of the average person, re-creating those lives for our reading pleasure. The emotion, humour and awkwardness in these tales is the closest thing to real-life I have read in an extremely long time and I would certainly recommend this book to anyone looking for a good book that will keep you on your toes.’ —Sabotage Reviews

‘There are some perfect little gems in this work; my particular favourite was the two-page story about a man who is jealous of his girlfriend’s pet chickens and how he gets his revenge.

It does give a funny, and sometimes wrenching view of the lives of us eccentric Brits.’ —NewBooks Magazine

About the author

TONY WILLIAMS’s All the Bananas I’ve Never Eaten won the Saboteur Award for best short story collection. His poetry includes The Corner of Arundel Lane and Charles Street and The Midlands. He lived in Sheffield for more than a decade before moving to rural Northumberland. He works in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Nutcase

TONY WILLIAMS’s All the Bananas I’ve Never Eaten won the Saboteur Award for best short story collection. His poetry includes The Corner of Arundel Lane and Charles Street and The Midlands. He lived in Sheffield for more than a decade before moving to rural Northumberland. He works in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

International House, 24 Holborn Viaduct, London EC1A 2BN United Kingdom

All rights reserved

Copyright © Tony Williams, 2017

The right of Tony Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2017

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-107-9 electronic

Nutcase

1

Mick Wilson was a man of steel. He would work a shift without cracking a smile and then go home and eat his tea with Marie and the kid, saying nowt, and then go on to the Dog & Partridge and stand at the bar and sink six pints, saying nowt, and then go home to bed. Where sometimes, but not often, he would insist with Marie.

‘You should use a johnny,’ she said. ‘We don’t want another, at our age.’

Sometimes he’d had enough of Marie. All she was interested in was her fucking soaps. So he ignored her and carried on.

The kid, who was called Davey, was a waste of space. He wore hair gel. He missed school to go smoking weed up the railway line. He sneered when Mick asked him about coming to the works.

‘Dead end that is. May as well cut out the middleman and get straight on the dole.’

This was back in the days when Thatcher was shagging the steel industry up the arse.

Mick said, try a cutlers shop then, or there was always labouring. But Davey signed up to college, which meant pootling off to a seminar three mornings a week and shagging that Becky and drinking cider in the afternoons. In the evenings, when Mick was sitting down to his tea and Davey was about to go off out with his mates, the two of them would have these terrible rows. Marie had to shut the living room door and turn up the telly.

It was worse if they happened to get in from the pub at the same time. They waved their arms and raved at each other, with their eyes rolling around their pissed faces. The swearwords spewed out of their mouths like sick. Then one day Mick completely lost it and gave Davey the old Wilson right hook. Except he lost his footing and missed, and put his fist through the frosted glass of the door.

All the time Marie was calling the ambulance, Davey was laughing and saying, ‘You stupid fucking old cunt. It’s a good job you fucking missed.’

The next week, Davey signed up to go and work on the rigs.

‘It’s good money,’ he said to Marie. She was crying the whole time he was packing up his stuff, and Becky was there saying, ‘We’ll be able to afford our own place now. You and Mick’ll have a bit of peace,’ but Marie just kept crying. Mick was downstairs with a face like thunder, off work with his cut hand, and Marie was snivelling.

‘I don’t know what the problem is,’ said Becky, who saw Davey as the perfect boy, pretty like Emilio Estevez but sensitive like Rob Lowe.

‘Oh, just fucking leave it,’ said Davey, and toted the holdall over his shoulder. Marie watched them down the street.

Becky was right: it was good money on the rigs, and it suited Davey fine, popping down every few weeks to shag her senseless and drink himself silly, then fuck off again on the train to Aberdeen where he didn’t have to think about her except for a lovey-dovey five-minute phone call before he went to sleep. Of course, with all the shagging she got up the duff, and it was good to miss all the throwing up too. But as it happened, he was on shore leave when the birth happened, so he could go in and see her the next day.

It was a boy. It looked like any other baby. They called it Ryan. ‘Him,’ said Becky, but Davey ignored her.

Because they’d sort of fallen out with Mick and Marie, and Davey was away most of the time on the rigs, Becky moved out of the flat and back in with her mum and dad in Leeds. When Davey came back, it wasn’t the same any more: Becky’s mum and dad were hanging around, in the way, and although he loved little Ryan there was only so much pushing prams round parks you could do. Having a baby also made it a lot harder to find time to jump in the sack. So sometimes he only called in for a night in Leeds and then pushed on to his mate Arshan’s in Sheffy for some spliffs and cans.

‘I’ll just fucking kill myself, then shall I,’ said Becky one time as he was getting up to go. ‘You just want to come down here and screw me and then you fuck off again. And what about Ryan? Don’t you care about him? He doesn’t even know who you are. He just looks at you funny like you was a stranger and grabs on tighter.’

‘And whose fault’s that, then?’ said Davey, even though he knew it was his.

And the funny thing was, she didn’t kill herself, but a month or so later Becky died of hypovolemic shock from an undiagnosed ectopic pregnancy, and that was that. Out of the blue. The doctor kept saying it was very rare, but these things did happen. ‘I bet they fucking do,’ said her dad, ‘only not to people who live in big houses out by Otley.’ Davey threatened to sue the hospital, but of course that was just a lot of hot air.

Becky’s mum was like a sad robot, keeping going and businesslike through her tears. She collared Davey. ‘I think it’s best if Ryan stays with us, don’t you? You’re not interested in the poor little bugger.’

Davey bristled up ready for a fight, but then he stopped and thought about it. Becky’s little brother and sister were there playing with Ryan and he was giggling and hiccuping, and Davey thought, ‘Christ yes, he’s well shot of me,’ so he said, ‘Aye, alright.’ And he got on the train back to Aberdeen with eight cans of Stella and told the poor sod next to him all about how he was a free man again, but wasn’t it sad that his girlfriend had died, he loved her really, but heigh-ho never mind, about a hundred and twenty-seven times.

Somehow life on the rigs, which had all been a big lads’ adventure when there was Becky to escape from, was a bit more depressing now that she was dead and he had a lot of time to think about her smile and the way she used to tickle his feet and so on. And he couldn’t count down the days till he called in to see her on the way to Arshan’s. There was just the rig – all that grey choppy sea heaving away day after day. He got a bit sick of it. And then it didn’t matter anyway, because he’d failed one of the drugs tests they did periodically, and he got the sack. So he turned up at Arshan’s with his old battered holdall and asked to kip on his sofa.

‘Sure,’ said Arshan, who figured he could do with another pair of hands when he went debt collecting.

It was good for a week or so, but then Arshan started to look pissed off when he came down in the morning to see Davey stretched out in front of the telly stinking of overnight farts. So Davey put his name down for a council flat, signed on, and got himself some cash-in-hand labouring. He sold a bit of Arshan’s weed for him, on the side. It was good money, all that, when you added it up.

When Marie called to say Mick had died, heart attack, he got on a bus and went to the funeral. He even took her flowers. And after that he called in every Sunday for a gravy dinner.

2

One time Davey popped round to Arshan’s to pick up a bag of skunk and there was this girl there, feet propped up on the arm of the sofa, doing her nails.

‘Hello,’ said Davey. ‘You’re alright.’

She looked him up and down and raised an eyebrow disdainfully, but you could tell she was impressed.

‘She’s alright,’ he said to Arshan, as they were setting up the scales on the kitchen table.

‘Who is?’

‘Her.’ Davey gestured next door. ‘Your new bird.’

‘Oh, Jasmine? It’s not like that. She’s, like, a second cousin or something. She’s staying for a while. Why? You like her?’

Davey did. So he took Jasmine out clubbing a few times, and they started to wake up in bed together the next morning with stinking heads and big healthy appetites like you get after a night of exercise. After a while she moved into his flat, and not long after that the exercise had its effect: they started sprogging off and the council moved them into a pebble-dashed semi.

‘Where are you from?’ Marie asked Jasmine when they met. ‘I mean originally.’

But Jasmine said, ‘Bolton,’ and poured herself another spritzer.

Marie said, ‘Should you be drinking that?’ and Jasmine said, ‘Nope.’

When Davey got back from the lav, they were sat in silence – Marie fuming, Jasmine cool as you like.

‘She’s common as, that one,’ said Marie, next time Davey came round on his tod. ‘You know they wipe their arse with their hands, don’t you?’

‘So do you, you daft cow,’ said Davey.

‘That’s not what I mean and you know it. I use toilet paper.’

‘So the only difference between you and her is a sheet of bogroll?’

‘Two sheets,’ said Marie in an icy whisper. ‘I fold it over.’

That was the end of the gravy dinners, but Davey and Jasmine were having more fun at home of a Sunday, listening to tunes and smoking some of that good weed of Arshan’s. Davey was a bit worried at first in case some other cousins who were a bit less chilled out than Arshan might come round and string him up by his balls, but Jasmine just laughed and said it wasn’t that sort of family. So they settled down and got quite well-known on the estate, walking the dog and selling weed, Davey knocking lads’ heads together if they got too rowdy, having these barbecues and letting the whole street come along.

In Davey’s head, it was like The Godfather. But instead of fruit stalls and big black sedans and pizza restaurants, it was boarded-up pubs and curry houses that did pizzas and burgers as well, deadlocks and barbed wire, flytipping and rats and burnt-out cars turning up in the woods. Then the local nature types would come and do a litter pick, with a special yellow tub for ‘sharps’, which meant the smackheads’ needles. Davey would let the dog chase them back to their branded Puntos and give them the rods while they glared out at him, calling the police on their mobile phones.

It was the sort of area where social workers said, ‘She’ll do what for a choc ice?’

And because Davey wasn’t a smackhead and Jasmine had been nearly twenty-two when they met, he thought of himself as Mr Responsible.

‘Mr Responsible for this country going to the dogs,’ said old Nev, who read the Express and had a heart condition. He thought people like Jasmine should be sent back to Pakistan or wherever, but he always had a good look at her arse when he stood behind her in Costcutter.

3

Davey and Jasmine had four kids: Kayla, Amy, Nick, and Aidan.

Kayla was the oldest and trained as a beautician, then married this mad bugger called Steven Cox and spent her whole life visiting him in Belmarsh. Kayla could have done something with her life – you could imagine her as a paramedic, or something, if things had turned out differently. Amy was the total opposite, so knackered by booze and smack at nineteen that Davey and Jasmine were already picking out tunes for the crematorium, but then she met this completely straight car salesman called Martin and went off to live in a Barratt home far away from anyone she could score off. Martin pampered her like a princess and kept the door locked, and it was all a bit creepy like he wanted her to rely on him so he could control her, but at least she was clean most of the time.

Nick was quiet and kept his head down, took up boxing at thirteen and went to technical college after he left school. Everyone liked him, though his little brother Aidan said he was as boring as rugby league. Nick had a face that made people feel like they could trust him. He appeared on the last series of Blind Date, but he wasn’t picked. It was such a shame.

Aidan was something else. Even as a little kid he was a mouthy bugger – right sarky, and hard with it. Swearing at teachers, setting fire to litter bins, smashing windows. Swearing at the police who picked him up and took him to school, then waiting till they’d gone and walking out again. That time he slapped the deputy head. Trouble, basically. Davey didn’t take to him (‘He’s a little shit’), but he was Jasmine’s favourite, and she let him get away with murder.

When he was nine, Davey came in and told Aidan to clean his trainers, but instead Aidan smeared them in dog shit and chucked them up on the roof of the bus stop.

‘You little bastard,’ said Davey, but Jasmine said it was just a prank and boys would be boys.

Another time, Davey asked Aidan to get him a can of Stella from the fridge and a spliff that he had ready rolled on the worktop. Aiden went, but after a while he didn’t come back so Davey went to look for him. He found him sitting up a tree in the park, drinking the beer and smoking the spliff. Davey started effing and blinding, as you would, till Aidan chucked the nearly full can at his head and half brained him. So Davey’s effing and blinding some more and shaking the tree, and Aidan’s laughing his head off and shouting, ‘Fuck off grandad!’ at the top of his voice.

All the local kids were standing round pissing themselves, and Davey was totally humiliated. When Aidan eventually came home, Davey gave him a bit of a whack, but Jasmine kept an eye on things to save him from a proper beating.

There was a pervert who used to hang about the wilder end of the park where it led on to the allotments and the back of the railway line. He used to hide in the bushes and flash at the kids who took a short cut through the fence to get to the estate. The kids never said anything to grown-ups about him because it didn’t occur to them. The flasher was just one of those dangers you had to cope with on your way home from school, like dog shit and barbed wire and older kids kicking you in the face.

He would step forward with a funny grin on his face and open his coat, and there would be this big red stiffy, all knobbly bits and wrinkles like a turkey’s neck. Usually the kids would just look at it and stop talking and go white, and keep walking till they were past.

As far as they knew he had never dragged anyone into the bushes and strangled them, but that was like obviously what he had in the back of his mind, and the kids sort of knew that when he stepped out in front of them and they saw his thing and felt sick.

Then one day Aidan was walking home with a few others. He had an empty Coke can that he had ripped open into a metal ribbon, for no particular reason, and he was swinging it round like a chain as he walked. The flasher stepped out from the bushes and opened his coat, and there was this horrible shining cock all close up in front of their faces.

They all stopped and stood there, and then Aidan stepped forward and swung the torn-open Coke can at the pervert’s cock. Straight away a load of blood spurted from the cock where the metal had cut it, down at the base towards the loose skin of his nutsack. Aidan jumped back out of the way of the spurting blood, and then they all stood and laughed at the flasher while he clamped his hands over his knob and tried to stop the blood coming out. But it wouldn’t stop coming. It was running all over his hands and down his legs, and his stiffy melted away in no time. Then the flasher pulled his coat back round him and ran off across the park, whispering, ‘You fucking little bastard,’ but not daring to shout in case it made the dog walkers turn round and look.

Aidan was a hero at primary school for like a week after that. Until the incident with the Mr Freezes in the girls’ bogs.

4

By this time, Davey and Jasmine had had another baby, a boy called Jay, and even though he had been an accident, Davey worshipped the ground he walked on. Now that Davey had calmed down a bit and wasn’t so bothered about getting completely off it all the time, it was like he was going to try to be a proper dad to Jay, and the others and in particular Aidan could fuck off out of it. Davey would buy these spenny glass jars of food for the baby, but Aidan was lucky if he got chips and scraps.

‘That’s charming, that is,’ said Aidan. ‘When you have a midlife crisis it’s your bird you’re supposed to trade in for a younger model, not your kids.’

But Davey had found out about Aidan nicking his fags, and he gave him a couple of hard cuffs to the lip.

When Aidan was twelve, Davey and Jasmine took little Jay away for a night or two at Filey. Davey said to Aidan, ‘Don’t burn the place down, will you,’ and gave him thirty quid. He told him to make sure he walked the dog, and said that if he didn’t and she shat everywhere, Aidan would be the one who had to clear it up.

The dog was a four-year-old staffie called Meg. She was alright with the family, but with strangers and other dogs she was like Gnasher. All yapping and straining and bared teeth and that. It gave Aidan a headache.

The first night he took her up to the park and let her run around a bit. She nearly caught a duck, and then had a go at this bloke’s pug. The bloke picked up the pug and was trying to bollock Aidan, but he still had Meg jumping up at him trying to get the pug, and he was having to sort of kick her away without getting bitten.

‘Sorry,’ said Aidan, trying to grab her collar to pull her away. The bloke was telling him off like an angry science teacher. Once Aidan had Meg on the lead he just walked off. On the way home he kept shouting at her, because although the bloke had been a dick about it, Aidan knew that it was Meg’s fault or more to the point Davey’s for not training her properly.

In the morning he took her out again, the other way this time, down to the woods at the other end of the estate. She ran off again, and this time when he caught up with her she had this cat by the back leg, ragging it about, trying to kill it. Aidan tried to get her jaws apart with his hands and ended up with cuts from her teeth and the cat’s claws. He picked up a big branch that was lying about and started laying into her with it. He had to hit the dog a lot of times before she’d let go of the cat, and then when he was dragging her home she was walking funny, sort of limping with her whole body.

When Davey got home and saw her he went apeshit. She had basically just laid in her bed the whole time since Aidan got her back. Davey got Jasmine to take her down the vet’s, and it turned out she had a broken leg and broken ribs and some internal injuries and had to be put down, and Jasmine and Davey narrowly avoided getting prosecuted for animal cruelty.

‘It weren’t my fault,’ said Aidan. ‘She was killing this cat.’

This time Jasmine didn’t stop Davey giving him a proper leathering. It was the first and last time that happened. After that, Aidan got too big for Davey to risk it. And after that the two of them permanently fell out, even though they lived in the same house, ignoring each other, staying out of each other’s way. All the rest of his life Aidan was missing one of his bottom front teeth because of the leathering he got for killing Meg the dog.

He got up to all sorts of other stuff, too. The usual: nicking stuff, getting pissed, skiving school. He burned a lad’s neck with a heated-up Zippo and tripped Ian Haynes in the Gala Bingo car park, and broke his leg. He paid Kelly Stone a quid to let him draw lipstick specs on her tits and a big gob where her belly button was, and then to pull her pants down to make a beard. It turned out Kelly Stone didn’t have much hair yet so it was like a wispy goatee. After that it seemed like he should do something else, so he threw a breeze block through the window of the oriental supermarket and then asked her to go down on him. But Kelly Stone ran away and didn’t seem to like him after that.

There was the time he opened all the cages in the pet shop, and the time he fired his air pistol at the tram from the roof of Jack Fultons Frozen Foods, and the paint he sprayed all over the gates of the meat paste factory. But he was usually smart enough not to get caught, and the day he killed his own dad’s dog was the mentallest thing he did, and the thing he was best known for, growing up.

5

There were all sorts of young lads who used to hang about on the estate. Some of them were dicks, but some of them were alright.

Nick knew these brothers, Carl and Connor, who used to go with him to the boxing gym. But old Stu had had to stop taking the sessions because of the trouble with his prostate, so they ditched the gloves and started meeting up for bare knuckle fights in the service yard behind the incinerator. It was just for fun. No money changed hands, and they had a rule that you couldn’t go for the other person’s face. After a couple of weeks they were all walking around really gingerly as if they had sunburn, with big bruises like mildew under their tops. But their faces were clean so their bosses and mums and social workers couldn’t bend their ears about it.

One Saturday morning when Aidan was about thirteen, he went with Nick to see if they could get this motorbike out of the canal. Some kid had nicked it the night before, ridden it up and down the Parkway and then chucked it in. One handlebar and mirror were visible above the surface of the water. Nick had this idea they could get it out and clean it up and sell it.

‘It’ll be knackered,’ said Aidan, but he went along anyway because it was a sunny day and there was fuck-all else to do.

There was already a crowd there when they arrived – Carl and Connor and one or two others, and a few little shrimps who were always hanging around. Connor had told one of the shrimps to wade out to the bike, and now he was sat on the bodywork with the canal up to his belly, enjoying the attention.

‘Take the other end of this,’ Connor was saying, and trying to fling out one end of a length of blue nylon rope so he could catch it.

‘Get off it and stand it up,’ someone else was shouting.

The others were saying, ‘Watch out for sharks,’ and, ‘Chuck summat at him.’ And, ‘Knock the little fucker off.’

And the little shrimp was giving them all the rods and grinning.

‘This is a waste of time,’ said Aidan, and sat down on the wall and smoked a Lambert & Butler.

After a while someone brained the shrimp with a lump of loose concrete they’d found on the towpath, and he fell in the canal and climbed out.

‘You fucking bastards,’ he kept saying. ‘I’m going to get my dad.’

They jeered, but the next thing a plod car pulled up on the bridge above them, and though they hadn’t done anything against the law they had enough sense to run. The next thing, they ended up in the service yard, which was sort of a safe haven for them, and Carl and Connor started setting up one of their fights.

Aidan got matched up against this dude called Foxy, who was nearly seventeen, and Nick said he was a half-cousin or something. He was walking round Aidan in a circle giving him these little jabs to the chest. Aidan hadn’t been to one of the fights before, and although he’d been told about the no faces rule, he hadn’t really been paying attention. So after Foxy had danced round him a couple of times, giving him these tap-taps on the chest, Aidan lamped him.

It wasn’t a proper hit – it didn’t catch him right. But it bloodied Foxy’s nose and he came right back at Aidan and caught him under the ear and stamped at his leg, and the next thing they were fully going at it, swinging each other round by the shirt and kicking the shit out of each other. Carl and Connor and Nick managed to pull them apart. Everyone was laughing and swearing, Aidan was spitting blood on to the floor, and Foxy was looking at where his sleeve had got torn. Nick was still holding Aidan’s arms but he said, ‘Alright, I’m not a fucking dog, you can let me off the lead now,’ and Connor was laughing and saying, ‘Calm down, twats,’ and they did.

On the way home Aidan said to Nick, ‘I could have had him, easy.’

‘Yeah,’ said Nick, like he wasn’t impressed.

But Carl said, ‘He’s not bad at fighting, your brother,’ to Nick, and even though he said it as if Aidan wasn’t there, you could tell it was meant to be a compliment.

6

A year or so after that, Arshan came to stay with Davey and Jasmine while his own house was being fumigated for bed bugs. He was worth a bob or two now – he ran his uncle’s restaurant and owned a couple of minicabs that operated out of a first-floor flat on Sharrowvale Road. Plus he was still shifting healthy amounts of weed. They sat out the back grilling Savers chicken breasts and drinking Red Stripe.

‘How are the boys getting on, then?’ asked Arshan, wiping his can across his brow. It was dead hot. Jasmine was sitting there in just her bra.

‘Nick’s doing alright. He’ll be done with his apprenticeship next year, and then he’ll be on good money.’

‘And Aidan?’

Davey made a face and guffed. ‘He doesn’t listen to a word I say. Whatever he ends up doing, it’ll be what Aidan wants. He won’t be told.’

‘He’s a big lad.’

‘Aye, and he’s got a big mouth, too. It’ll get him into trouble. I try not to let it get to me but I know we’re going to have an almighty bust-up one day.’

After the chicken they carved up a mint Viennetta. Arshan said, ‘A few of us are going to Amsterdam next weekend. It’ll be carnage. We could take him along, get him out of your hair for a few days?’

‘Awesome,’ said Davey, and it was all arranged.

‘No whores or Class As,’ said Jasmine, fiddling with her straps.

There was a group of twelve of them. ‘Like the fucking apostles,’ said Arshan, but they all gave him blank looks. They got a National Express to Newcastle then piled on to the ferry. Arshan had said to bring some cans so they didn’t have to pay the ferry prices. Aidan had a bag of Carlings from Londis, a couple of packets of ready salted and a steak bake.

They sat in the lounge area and drank for a bit, then headed off on deck, some to chuck up and the others to laugh at them and throw sandwiches for the birds. Aidan came inside again and played for a while on an old Virtua Cop 3 console, trying to impress these posh girls from Harrogate, but then their teacher turned up. So he went back to the seats where his stuff was, but all his cans had gone. There was just a few crisps trodden into the carpet.

He steamed round the lounge and then out on deck, and found this mate of Arshan’s, Shaun something, finishing a mouthful of food over a Carling.

‘Have you had my beer?’ said Aidan.

‘You what?’ said Shaun something.

‘You heard,’ said Aidan, and caught him a smack round the side of the head.

This Shaun wasn’t much older than Aidan, and he wasn’t half the size. Before he’d got up Aidan had given him a few more in the head, and the last one sent his head back hard against a metal stairway. He gave him a few kicks in the ribs, and then heard voices coming so walked quickly off round the corner.

Back in the lounge they asked him if he’d seen Shaun. ‘Yeah,’ he said, jabbing his thumb over his shoulder. ‘Some fucker’s kicked his head in. It’s them United fans.’

‘Is it fuck,’ said Arshan, looking into Aidan’s face, which was kind of shining as if he was really high or pissed. But he only said, ‘We’d better go and make sure he’s alright, then.’

Some dude, a big steroid-popper who was Shaun’s uncle or something, had steam coming out of his ears, but he couldn’t get at Aidan there in full view of everyone. ‘You’ve fucking had it, sunshine,’ he said, drawing his finger across his throat.

Aidan blew him a kiss.

‘Oh, for fuck’s sake,’ said Arshan.

Anyway, it didn’t matter because the ferry CCTV had caught the whole thing, and when they got into IJmuiden the Dutch police were waiting. Aidan had to stay on the ferry to go back and face the music in Newcastle. Jasmine had to come up on the train and pay fifty quid police bail.

‘Your dad’s off his nut,’ she said. ‘You can’t come home or he’ll wring your neck. And anyway Shaun’s uncles’ll kill you if they find you on the estate.’

They decided that Aidan should stay up in Newcastle for the time being. There was a bloke called Ross who ran an iffy business delivering white goods and furniture, who Jasmine knew from way back.

‘Is he an ex?’ said Aidan.

‘He wishes.’

7

They met Ross in the car park of a pub in Byker. He said he’d heard Aidan was a real ball-ache, but he looked strong so he’d take him. ‘There’s a spare room at my flat. No shagging my daughter. Do as I say and we’ll be fine.’

‘How old’s your daughter?’ asked Aidan, and Jasmine clipped him round the ear.

‘Shut up,’ she said. ‘For all you know she’s your half-sister.’

They both looked at her.

She counted out two hundred quid in twenties and gave it to him. ‘Don’t take any shit from anyone,’ she said, ‘but don’t give none either. And use a rubber.’

Aidan grinned. Then they all got in the front of Ross’s Transit, dropped her at the Metro station and drove up the dual carriageway to the depot.

‘Fit, your mum,’ said Ross.

Aidan put his feet up on the dashboard and said nothing.

The depot turned out to be a grotty warehouse unit where some Somali lads were hefting boxes about on sack barrows and arguing with each other in Somalian.

‘What are they saying?’ said Aidan.

‘Who gives a fuck?’ said Ross, and bogged off again in his van.

Whether they were illegals wasn’t clear, but it was obviously cash in hand. Every few minutes a van would arrive back, and they’d stack it up quick with stuff, and then the driver and his mate would hop in and speed off to deliver it. Aidan sat on his arse and watched them, drinking a banana Frijj. A couple of times they asked him to help, but he just laughed at them. ‘Work harder!’ he said. ‘Lazy bastards!’

After Ross had got back, the Somalians had a word with him, and he came and had a word with Aidan.

‘It’s pissing them off a bit, you sat about not helping. They say you’re looking for a hiding.’

‘That’d liven things up. I reckon I could take out three of them before they had me.’

Ross shook his head. ‘You haven’t got a clue, have you? Just do some fucking work. I’ve had word HMRC might come down here later, and we need to get all this crap shifted before they do.’

So Aidan leapt up and started grappling boxes around. They were all amazed at what he could do, for a kid. He lifted washing machines on his tod, one after another, and had to be stopped in the end when the transit he was loading was right down on its axles. The Somalis were more friendly then, offering him fags, and when the gear was all gone and they were about to make themselves scarce, in case HMRC did show up (although this was probably a lie Ross made up to make them work quicker), they gave Aidan a pouch of khat.

‘You did OK,’ said Ross on the way home. ‘Sometimes you just have to keep your head down. They’re good lads. You’ve got a face for attracting trouble – you don’t need to go looking for it.’

Yeah, yeah – he sounded like Davey. Aidan looked out of the window at the kebab shops and bookies and the girls in short skirts walking down the pavement.

‘I bet you wank about my mum, don’t you?’ he said.

‘Sometimes,’ said Ross.

8

Life with Ross was alright. Some days Aidan would go to work with him, picking stuff up, lugging it around, in return for his board and a bit of cash. Some days he wouldn’t bother, but would just lie about in the morning watching daytime telly. Ross’s daughter Sally would walk through wrapped in towels from the shower and they would be rude to each other in that spiky flirting way, but Aidan wasn’t quite sure how to take things further. She was like nineteen or something, and he didn’t want to come across as a stupid kid. After she’d gone to college he might toss himself off, and then get dressed and have a wander up through the estate.

There was a pub with a flat roof called The Coal Barge, and Aidan took to hanging about the beer garden in the afternoons with a man called Eddie. Eddie was a doler with smudged old tattoos on his hands, and a bit creepy. What was he doing hanging around with a young lad? But Aidan figured he could kick the shit out of him no probs, so it was safe to let him buy him beer. Eddie went on about all sorts of shit – Tories, pervs, Mackems, MPs, Shearer and coke. He said he’d been invalided out of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, but it seemed more likely he was just a lying twat.

He’d say, ‘Scargill had it right. A line of coppers and a line of us, going at it. Class war. That’s what it’s all about.’

‘Who’s Scargill?’ said Aidan, and Eddie cracked a wry face and pulled on his rollie.

Below the pub was a little park, and one day Aidan saw Sally come in and sit down on a bench and sit there crying.

‘What’s up with her,’ said Eddie. ‘I’d cheer her up.’