Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

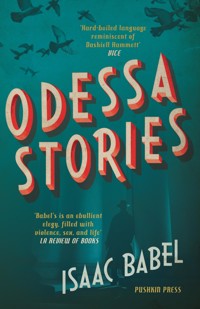

A new mass-market edition of the acclaimed stories of violence, crime and sex 'One of those "where have you been all my life?" books'Nick Lezard, Guardian In the city of Odessa, the lawless streets hide darker stories of their own. From the magnetic cruelty of mob boss Benya Krik to the devastating account of a young Jewish boy caught up in a pogrom, Odessa Stories uncovers the tales of gangsters, prostitutes, beggars and smugglers: no one can escape the pungent, sinewy force of Isaac Babel's pen. Translated with precision and sensitivity by Boris Dralyuk, whose rendering of the rich Odessan slang is pitch-perfect, this acclaimed new translation of Odessa Stories contains the grittiest of Babel's tales, considered by many to be some of the greatest masterpieces of twentieth-century Russian literature. Isaac Babel was a short-story writer, playwright, literary translator and journalist. He joined the Red Army as a correspondent during the Russian civil war. The first major Russian-Jewish writer to write in Russian, he was hugely popular during his lifetime. He was murdered in Stalin's purges in 1940, at the age of 45.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 203

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PUSHKIN PRESS

Odessa Stories

‘The salty speech of the city’s inhabitants is wonderfully rendered in a new translation by Boris Dralyuk… Hardboiled language reminiscent of Dashiell Hammett’

Vice

‘One of those “where have you been all my life?” books’

Nicholas Lezard, Guardian

‘Babel is required reading’

Eileen Battersby, Irish Times Books of the Year

‘Sparkling, wily and loose-tongued… Babel’s dialogue calls for a daring translator… Boris Dralyuk delivers brilliantly’

TLS

‘A gripping, poignant collection of stories about his home city by one of the leading lights of European modernism’

New European

‘Elegiac, but not in the usual sense: Babel’s is an ebullient elegy, filled with violence, sex, and life’

LA Review of Books

‘This is a wonderful, highly readable collection of stories’

The London Magazine

‘[Isaac Babel’s stories] opened a door in my mind, and behind that door I found the room where I wanted to spend the rest of my life’

Paul Auster

‘Electric, heroically wrought prose’

John Updike

CONTENTS

ODESSA STORIES: ISAAC BABEL AND HIS CITY

Boris Dralyuk

AN OLD JOKE: A Jew is kvetching (complaining, for the uninitiated) to a stranger about never having had any children. “But that’s the way it is with my family,” he groans. “My father was childless, and so was my grandfather before him…” Flummoxed, the stranger asks, “Then where did you come from?” The Jew replies, “From Odessa.”

Why start there? Well, as the saying goes, there’s a grain of truth in every joke. (And when it comes to Odessa, the scales tip altogether: the version I grew up hearing is that there’s a grain of joke in every joke.) In its wily way, this little gag tells us a whole lot about my native city. Who is this fellow, anyway? All Jews in jokes kvetch—it’s what they do—but his griping is over the top, excessively schmaltzy and, in the end, entirely absurd. Is our hero off his nut, a far-gone luftmensch? Or is he trying to pull one over on the stranger, playing for sympathy so as to separate a fool from his money? That would make him a rogue, a schnorrer with chutzpah to spare.

Humour and dreamy eccentricity, daring and double-dealing—part and parcel of the Odessa myth, which has grown up around this notoriously lawless provincial capital on the coast of the Black Sea since its founding in 1794. As Jarrod Tanny argues in City of Rogues and Schnorrers, his marvellous study of the myth’s evolution, “Much like Shanghai, New Orleans, and San Francisco’s Barbary Coast, old Odessa was both venerated and vilified as a city of sin—heaven for some, hell on earth for others—a haven for smugglers, thieves, and pimps who boasted of their corruption through endless nights of raucous revelry.”1 What set this particular band of “smugglers, thieves, and pimps” apart is that many of them were Jews, the most adventurous machers among the thousands of their co-religionists who poured into the “Russian Eldorado” from Eastern European shtetls. And they weren’t just adventurers: they were funny, making your sides split with laughter as they slit the side of your purse.

There weren’t many other places these Jewish fortune-seekers could have gone. In the nineteenth century, Odessa, with its major commercial port, was the most cosmopolitan and least tradition-bound city in the Russian Empire’s Pale of Settlement, which was home to half of the world’s Jews. Odessa’s economy boomed and its population kept doubling in size about every other decade, reaching 400,000 by 1900. Approximately 140,000 of that 400,000 were Jews, an enormous proportion by any standard and the second largest Jewish population in the Empire after Warsaw—which had more Jews than any city in the world other than New York.

To be sure, Jews left an indelible mark on the cultures of Warsaw and New York, as well as of Vilnius and Kiev, but Odessa, the fate of which has been so thoroughly intertwined with Jews from the start, became a uniquely Jewish city. Odessa’s distinctive and instantly recognizable language is a Russian dialect spiced with Yiddish words and grammatical structures, and, perhaps even more importantly, inflected by Yiddish intonation and pronunciation; it is spoken by Odessa’s Jews, Ukrainians, Russians and Greeks alike. The city’s transgressive culture heroes—thieves and gangsters like Sonya the Golden Hand (Son’ka Zolotaya Ruchka, née Sheyndlya-Sura Solomoniak, 1846–1902) and Mishka the Jap (Mishka Yaponchik, né Moyshe Vinnitsky, 1891–1919)—were regarded with awe by Odessans of all backgrounds, and tales of their feats spread like wildfire through the Russian-speaking world. Their fame hasn’t waned: both Sonya and Mishka were recently the subjects of big-budget Russian TV mini-series (airing in 2007 and 2011, respectively).

The fact that these dubious figures were lionized indicates the darker side of Jewish history, not just in lawless Odessa but throughout the Russian Empire. Whatever they were in real life (and let’s face it, they were psychopaths), in the Jewish imagination they became Robin Hoods, social bandits using their natural gifts to triumph over systemic discrimination and—at least in the case of Mishka—to redistribute the oppressors’ wealth among the community. It serves to recall that old Odessa wasn’t just the land of opportunity: it was the site of many horrific pogroms, during which hard-boiled Jewish gangsters rose like golems to defend their people.

Sonya and Mishka are by now so thoroughly cloaked in legend that they might as well be entirely fictional—and, indeed, it is fiction proper, along with poetry, popular song and film, that has fixed the myth of Odessa in the public imagination. There are statues of Ostap Bender, the quip-spewing Soviet trickster at the centre of Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov’s picaresque novels The Twelve Chairs (1928) and The Golden Calf (1931) in sixteen Russian and Ukrainian cities, and the “criminal” songs popularized by Leonid Utyosov (1895–1982), one of Odessa’s proudest citizens and Stalin’s favourite performer, are still sung—Odessan accent and all—by Russian-speakers wherever the winds of history have tossed them. But no author has done more to solidify the myth, and to raise Odessan lore to the level of art, than Isaac Babel (1894–1940), one of the greatest prose stylists of the twentieth century and a victim of Stalin’s terror.

Born in Moldavanka, Odessa’s counterpart to London’s Whitechapel and New York’s Lower East Side, Babel was raised in a well-heeled Jewish family. He spent his early childhood in the city of Nikolayev (now Mykolaiv, Ukraine). When the boy was eleven, the Babels relocated to a nice part of Odessa, but the budding author’s affinity for life’s seamy, variegated underbelly drew him back to Moldavanka, where he collected material for a cycle of stories that transformed the exploits of Mishka the Jap and his ilk into a modernist epos. Published in newspapers and journals in the early 1920s contemporaneously with his Red Cavalry stories, which chronicled his service in the Red Army during the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–21, Babel’s Odessa Stories consolidated the city’s myth, never shying away from its darker elements. His depiction of the Mishka-like Benya Krik, “King” of Odessa’s underworld, is bracingly ambiguous—alluring and terrifying in equal measure. This volume also features tales that draw on Babel’s childhood and youth in Odessa and Nikolayev, including ‘The Story of My Dovecot’, perhaps the most harrowing narrative of anti-Semitism in both its systemic and convulsively violent aspects ever constructed.

Of course, what really keeps you hanging on Babel’s every word are the words themselves, that rich Odessan argot. As Froim the Rook says of Krik, “Benya, he doesn’t talk much, but what he says, it’s got flavour. He doesn’t talk much, but when he talks, you want he should keep talking.” This, after the gutsy Benya barges in on the one-eyed gang boss and declares, “Look, Froim, let’s stop smearing kasha. Try me.” Once Froim gets a taste of that “kasha”, he can’t help giving Benya a try.

The language of Odessa, with its Yiddish inflections and syntactic inversions, its clipped imperatives and its freight of foreign words, was in the air all around me as I was growing up. Little did I know that a similar melting pot, New York’s Lower East Side, had made a similar “kasha” out of English at around the time Benya’s archetypes were raising hell in Moldavanka. When I discovered the novels of Samuel Ornitz, Michael Gold, Henry Roth and Daniel Fuchs, the plays of Clifford Odets and the stories of Bernard Malamud, I felt right at home.2 I was also fatefully drawn to the Black Mask school of detective fiction, which brought a tough, vivid urban vernacular—the language of gunsels and private eyes—into the mainstream. My English Benya is, linguistically, a product of my misspent youth with the pulps. But I don’t think I’m doing him a disservice by having him tell a kid, “You got words? Spill.” After all, Isaac Babel and Dashiell Hammett were born only a month and a half apart in 1894.

The liberties I’ve taken with the dialogue are not terribly radical. In general, I’ve tended toward concision, feeling it more important to communicate the tone—the sinewy, snappy punch—of the gangsters’ verbal exchanges than to reproduce them word for word. A longer phrase that rolls off Benya’s tongue in Russian may gum up the works in English. For instance, in the original Russian, Benya refuses to smear kasha “on a clean table”. In English, “on a clean table” felt superfluous. Both the tone and the image were sharper without it. To my ear, the pithy “let’s stop smearing kasha” has the force and appeal of an idiom encountered for the first time. In other places, I’ve sought equivalents for idiomatic Russian (or Odessan, or even simply Babelian) turns of phrase. For example, when an old matchmaker warns Froim that his daughter is hungry for romance, he puts it this way: “I see your child is asking to be let out onto the grass” or “to pasture”. The Russian is concise and clear in its meaning. A literal translation would either be cluttered or semantically hazy. I opted for “I see your baby girl is champing at the bit”, which is clear, full of character and preserves the thread of equine imagery running through the tale.

Naturally, Babel’s narrator—the young Odessan romantic with glasses on his nose and autumn in his heart—demanded a different tack. I’ve tried to render his vision as precisely as possible. Fidelity was indeed a matter of vision. What, for example, do the snaking tables in the courtyard do at the start of ‘The King’: “coil” (as an earlier translation has it) or “wind” through it? It’s hard to imagine the long wooden tables coiling; they’re probably set up lengthways in two or three sinuous columns, as these things are still done in Odessa. And what exactly does Lyubka the Cossack do to the drunken sailor: “punch” (as the same earlier translation has it) or “push” him with her fist? On that warm Odessan night, with everyone’s head swimming in Bessarabian wine, all movement is slow and gentle—even the violence.

As for tone, I took every opportunity to inflect the English text with lyrical Yiddish inversions, mirroring the Yiddishized Russian (e.g. “and they sang in rich voices, these patches of orange and red velvet”). To sum up, my priorities were visual precision and lyricism in the narrative, and piquancy in the dialogue.

Previous translators have taken what I believe to be the gangsters’ noms de guerre as surnames. I have rendered them all in English—for instance, Lyova “the Russkie” (Katsap—a derogatory Ukrainian term for Russians), Lyovka “the Bull” (Byk), Kolka “the Pin” (Shtift) Pakovsky and Misha “the Bullseye” (Yablochko). The nickname of one-eyed Froim “the Rook”, a major character, has usually remained unrendered, but the early story ‘Justice in Quotes’ makes it clear that “Grach” (Rook) is indeed a nickname, alluding to Froim’s corvine features and his black soul, and that his surname is actually Shtern.

*

Success has many fathers. If you find something to like in this translation, then most of the credit goes to my brilliant editors at Pushkin Press, Gesche Ipsen, Julia Nicholson and Bryan Karetnyk; to my indispensible friends and consiglieri Robert Chandler, Maria Bloshteyn, Michael Casper, John Shannon, Roman Koropeckyj, Jeff Brooks, Emily Finer and Michael Alpert; to Rebecca Taylor, who commissioned an earlier version of this introduction for Jewish Renaissance magazine; and, above all, to my mother Anna Glazer, with whom I picked over every word. If nothing here pleases you, blame a childless schnorrer from Odessa.

NOTES

1 Jarrod Tanny, City of Rogues and Schnorrers: Russia’s Jews and the Myth of Old Odessa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), p. 2.

2 In her excellent study Jewish Gangsters of Modern Literature (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000), Rachel Rubin links Babel’s work to that of Gold, Ornitz and Fuchs.

PART I

Gangsters and Other “Old Odessans”

THE KING

THE WEDDING CEREMONY was over and the rabbi lowered himself into an armchair, then he stepped outside and saw the tables set up all along the courtyard. There were so many of them that they stuck their tail right through the gate onto Gospitalnaya Street. The velvet-draped tables wound through the yard like snakes with patches of every colour on their bellies, and they sang in rich voices, these patches of orange and red velvet.

The flats had been turned into kitchens. A meaty flame, a plump, drunken flame, gushed through their sooty doors. The aged faces, wobbly jowls and grimy breasts of housewives baked in its smoky rays. Sweat rosy as blood, rosy as the foam on a mad dog’s lips, streamed down these piles of overgrown, sweetly stinking human flesh. Three cooks, not counting the hired help, were preparing the wedding feast, and over them reigned the eighty-year-old Reyzl—tiny, humpbacked, and traditional as a Torah scroll.

Before the feast got going, a young fellow nobody knew wormed his way into the yard. He asked for Benya Krik. He took Benya Krik aside.

“Listen, King,” said the young man, “I’ve got a couple words for you. Aunt Hannah sent me, from Kostetskaya Street…”

“All right,” said Benya Krik, whom everyone knew as the King. “You got words? Spill.”

“Aunt Hannah, she told me to tell you there’s a new chief in town, took over the police station yesterday…”

“Knew about that the day before yesterday,” said Benya Krik. “Keep talking.”

“The chief, he got all the cops together, gave them a speech…”

“New broom sweeps clean,” said Benya Krik. “Wants a raid. Keep talking…”

“But when, King—you know when he wants it?”

“The raid’s tomorrow.”

“King, it’s today.”

“Who says, kid?”

“Says Aunt Hannah. You know Aunt Hannah?”

“I know Aunt Hannah. Keep talking.”

“…The chief got the cops together and gave them a speech. ‘We’ve got to stifle that Benya Krik,’ he says, ‘because where there’s an emperor, there can’t be no king. Today, when Krik’s marrying off his sister and they’re all in one place, that’s when we raid…’”

“Keep talking.”

“…Then the coppers, they got scared. They said, if we raid today, when Benya’s having a feast, he’s gonna be sore, gonna waste a lot of blood. So the chief says, pride’s more important…”

“All right, get going,” said the King.

“So what do I tell Aunt Hannah, raid-wise?”

“Tell her Benya knows, raid-wise.”

And he left, this young man. Three of Benya’s friends left too. They said they’d be back in half an hour. And they came back in half an hour. That’s all there was to it.

The guests weren’t seated according to seniority. Foolish old age is no less pitiful than cowardly youth. And they weren’t seated according to wealth. A heavy wallet is lined with tears.

The bride and groom had first place at the table. This was their day. Next came Sender Eichbaum, the King’s father-in-law. That was his right. And Sender Eichbaum’s story is worth hearing, because it isn’t a simple story.

How did Benya Krik, gangster and king of the gangsters, become Eichbaum’s son-in-law? How did he become the son-in-law of a man who owned no fewer than sixty milk cows? It all goes back to a shakedown. Only a year ago Benya wrote Eichbaum a letter.

“Monsieur Eichbaum,” he wrote, “I ask you to come to 17 Sofiyevskaya Street tomorrow morning and place twenty thousand roubles under the gate. If you do not do this, what awaits you is unheard of, and you will be the talk of all Odessa. Respectfully, Benya the King.”

Three letters, each more direct than the last, went unanswered. So Benya took certain measures. They came at night—nine men with long sticks in their hands. The tops of the sticks were wrapped in tarred hemp. Nine blazing stars lit up over Eichbaum’s stockyard. Benya knocked the locks off the shed and led the cows out, one by one. A guy with a knife stood waiting. He tipped each cow over with one blow and plunged the knife into its bovine heart. The torches blossomed like fiery roses on the blood-soaked ground, then shots rang out. Benya started shooting to drive away the milkmaids, who’d come running to the cowshed. And the other gangsters followed suit, firing shots in the air, because if you don’t shoot in the air you could kill someone. And then, when the sixth cow fell at the King’s feet with a dying moo, Eichbaum himself ran into the yard in nothing but his long johns and asked:

“Benya, what’s this?”

“Monsieur Eichbaum, I don’t get my money, you don’t keep your cows. Simple as that.”

“Step inside, Benya.”

Inside they came to terms. The slaughtered cows were split evenly between the two of them. Eichbaum was guaranteed immunity and issued a stamped certificate to that effect. But the miracle—that came later.

During the shakedown, on that terrible night when the stabbed cows bellowed and their calves slipped and slid in maternal blood, when the torches danced like black virgins and the milkmaids squirmed and screamed before the barrels of friendly Brownings—on that terrible night, old man Eichbaum’s daughter, Celia, ran out into the yard in her nightshirt. And the King’s triumph proved to be his downfall.

Two days later, without any warning, Benya returned all the money he had taken from Eichbaum, and then he came calling in the evening. He had an orange suit on, a diamond bracelet gleaming beneath his cuff; he came into the room, greeted Eichbaum, and asked for his daughter Celia’s hand in marriage. The old man nearly had a stroke, but he stood up. He still had a good twenty years in him.

“Listen, Eichbaum,” said the King, “when you die, I’ll bury you at the First Jewish Cemetery, right by the gates. I’ll put up a tombstone of pink marble, Eichbaum. I’ll make you an Elder of the Brodsky Synagogue. I’ll abandon my profession, Eichbaum, and we’ll partner up in business. We’ll have two hundred cows, Eichbaum. I’ll kill all the other dairymen. No thief will walk down the street where you live. I’ll build you a dacha by the beach, at the sixteenth tram stop… And remember, Eichbaum, you weren’t no rabbi in your youth either. Just between us, that will didn’t forge itself, did it? And you’ll have the King for a son-in-law, not some snot-nosed kid—the King, Eichbaum…”

And Benya Krik, he got his way, because he had passion, and passion rules the world. The newlyweds spent three months in fertile Bessarabia, swimming in grapes, plentiful food and the sweat of love. Then Benya returned to Odessa so as to marry off his forty-year-old sister, Dvoyra, who had a goitre that made her eyes bulge. And now, having told the story of Sender Eichbaum, we can get back to the wedding of Dvoyra Krik, the King’s sister.

At this wedding they served turkey, roast chicken, goose, gefilte fish and fish soup in which lakes of lemon glimmered like mother-of-pearl. Flowers swayed above the dead goose heads like lush plumage. But does the foamy surf of Odessa’s sea wash roast chickens ashore?

On that starry, that deep blue night, the noblest of our contraband, everything for which our region is celebrated across the land, did its destructive, seductive work. Wine from abroad warmed stomachs, broke legs in the gentlest way possible, numbed brains and brought up a belching as sonorous as the call of a battle horn. The black cook from the Plutarch, which had come in from Port Said three days earlier, smuggled in round-bellied bottles of Jamaican rum, oily Madeira, cigars from Pierpont Morgan’s plantations and oranges from the environs of Jerusalem. That’s what the foamy surf of Odessa’s sea washes ashore; that’s what Odessa’s paupers can hope to get their hands on at Jewish weddings. Odessa’s paupers got their hands on Jamaican rum at Dvoyra Krik’s wedding, sucked up their fill like treyf pigs and raised a deafening clatter with their crutches. Eichbaum undid his vest, gazed at the stormy gathering with narrowed eyes and hiccupped lovingly. The orchestra played flourishes. It was like a divisional parade. Flourishes—nothing but flourishes. The gangsters, who sat in serried ranks, were at first put off by the presence of strangers, but then they loosened up. Lyova the Russkie smashed a bottle of vodka over his beloved’s head. Monya the Gunner fired a shot in the air. But their enthusiasm reached its peak when, in accordance with ancient custom, the guests began to present the newlyweds with gifts. The synagogue shammeses leapt onto the tables and sang out the number of tendered roubles and silver spoons to the sound of the raucous flourishes. And here the King’s friends showed the true worth of Moldavanka’s blue blood and its yet unextinguished chivalry.1 Their careless gestures filled silver trays with gold coins, jewelled rings and coral necklaces.

These aristocrats of Moldavanka were squeezed into crimson vests, rufous jackets gripped their shoulders, and their fleshy legs nearly burst through leather of the purest azure. Standing tall and sticking out their bellies, the gangsters clapped to the music, shouted “give ’er a kiss” and threw the bride flowers, while she, forty-year-old Dvoyra, sister of Benya Krik, sister of the King, disfigured by disease, with an outsize goitre and bulging eyes, was perched on a mountain of pillows beside a frail boy who had been purchased with Eichbaum’s money and was numb with anguish.

The rite of gift-giving was coming to a close, the shammeses had grown hoarse and the bass wasn’t getting along with the fiddle. A faint odour of burning suddenly wafted over the courtyard.

“Benya,” said Krik’s papa, an old drayman who was known as a roughneck even among other draymen. “Know what I think, Benya? What I think is the soot’s burning…”2

“Papa,” the King told his drunken father. “Please, I ask you, eat a little, drink a little, and don’t pay no mind to that nonsense…”

And Papa Krik followed his son’s advice. He ate a little, drank a little. But the cloud of smoke grew more and more noxious. Some patches of sky were turning pink. And a flame’s tongue had already shot up into the heavens like a sword. The guests rose in their seats and began sniffing at the air, and their women squealed. The gangsters exchanged glances. Benya alone, noticing nothing, was inconsolable.

“They’re spoiling my feast,” he cried, full of despair. “Friends, please, I ask you, eat, drink…”

But at that moment the same young man who’d come earlier appeared in the yard.

“King,” he said. “I’ve got a couple words for you…”

“All right, spill,” said the King. “You’re never short a couple words…”

“King,” the unknown young man said and chuckled. “Funny thing, the police station, it’s burning like a candle…”

The shopkeepers were numb. The gangsters grinned. Sixty-year-old Manya, matriarch of the Slobodka3 crew, stuck two fingers in her mouth and gave a whistle so shrill it sent those around her reeling.