11,12 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

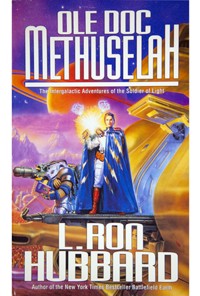

If you love Star Trek, you will love Ole Doc Methuselah.

He’s renowned throughout the universe, a star among stars. . . Ole Doc Methuselah is his name, and saving the universe is his game. He journeys with his bag of tricks to the far corners of the cosmos, cutting out the corruption and cruelty, and containing the warped psychology plaguing mankind.

So if you’re looking for an adventure to remember, this is just what the doctor ordered.

“Classic adventures by a classic writer.” —Roger Zelazny

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 386

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1992

Ähnliche

Selected fiction works by L. Ron Hubbard

FANTASY

If I Were You

Slaves of Sleep & The Masters of Sleep

Typewriter in the Sky

SCIENCE FICTION

Battlefield Earth

Final Blackout

The Great Secret

The Kingslayer

The Mission Earth Dekalogy:*

Volume 1: The Invaders Plan

Volume 2: Black Genesis

Volume 3: The Enemy Within

Volume 4: An Alien Affair

Volume 5: Fortune of Fear

Volume 6: Death Quest

Volume 7: Voyage of Vengeance

Volume 8: Disaster

Volume 9: Villainy Victorious

Volume 10: The Doomed Planet

Ole Doc Methuselah

To the Stars

HISTORICAL FICTION

Buckskin Brigades

Under the Black Ensign

MYSTERY

Cargo of Coffins

Dead Men Kill

Spy Killer

WESTERN

Branded Outlaw

Six-Gun Caballero

A full list of L. Ron Hubbard’s fiction works can be found at GalaxyPress.com

*Dekalogy—a group of ten volumes

Thank you for purchasing Ole Doc Methuselahby L. Ron Hubbard.

To receive special offers, bonus content and info on new fiction releases by L. Ron Hubbard, sign up for the Galaxy Press newsletter.

Visit us online at GalaxyPress.com

OLE DOC METHUSELAH

© 1992 L. Ron Hubbard Library. All Rights Reserved.

Any unauthorized copying, translation, duplication, importation or distribution, in whole or in part, by any means, including electronic copying, storage or transmission, is a violation of applicable laws.

Cover Art: Gerry GraceCover artwork: © 1992 L. Ron Hubbard Library. All Rights Reserved.

Mission Earth is a trademark owned by L. Ron Hubbard Library and is used with permission. Battlefield Earth is a trademark owned by Author Services, Inc. and is used with permission.

Print ISBN: 978-1-59212-911-9EPUB edition ISBN: 978-1-59212-917-1Kindle edition ISBN: 978-1-59212-912-6Audiobook ISBN: 978-1-59212-393-3

Published by Galaxy Press, Inc.7051 Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood, California 90028

GalaxyPress.com

Contents

Introduction

Preface

Ole Doc Methuselah

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Her Majesty’s Aberration

The Expensive Slaves

The Great Air Monopoly

Plague

A Sound Investment

Ole Mother Methuselah

About the Author

Glossary

Introduction

It was the autumn of 1947—the tenth year of a golden age for John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction, the magazine that had reshaped and redefined science fiction into its modern form. Campbell, coming to the editorship of Astounding at the age of 27 in October, 1937, had tossed out within a year or two most of the old-guard writers who had dominated the magazine, and had brought in a crowd of bright and talented newcomers: such people as Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, L. Ron Hubbard, A. E. van Vogt, L. Sprague de Camp, Theodore Sturgeon, Fritz Leiber, Lester del Rey. They—and a few veterans like Jack Williamson and Clifford D. Simak—wrote a revolutionary new kind of science fiction for Campbell, brisk and crisp of style, fresh and lively and often irreverent in matters of theme, plot and characterization. The readers loved it. Astounding was the place where all the best stories were—many of them now classics, which have stayed in print for fifty years—and both the magazine and its larger-than-life editor were regarded with awe and reverence by its readership and by most of its writers as well.

Hubbard—whose famous writing career had begun in the early 1930’s in such wild-and-wooly pulps as Thrilling Adventures, Phantom Detective, Cowboy Stories, and Top Notch, and the more prestigious magazines as Argosy, Adventure, WesternStories, PopularDetective and FiveNovelsMonthly, had been especially commissioned by publishers Street & Smith to write for Astounding magazine’s editor John W. Campbell Jr. in 1938. At 27, just a few months younger than Campbell, he was already the author of millions of published words of fiction, and Campbell wanted him for his knack of fast-paced story-telling and his bold ideas. Soon Hubbard was a top figure in the Astounding of the 1940’s and in its short-lived but distinguished fantasy companion, Unknown, with such Hubbard stories and novels as “The Tramp” (1938), “Slaves of Sleep” (1939), “Typewriter in the Sky” (1940), “Final Blackout” (1940), “Fear” (1940), “The Case of The Friendly Corpse” (1941) and “The Invaders” (1942). But then Hubbard too went off to military service, and his contributions to Campbell’s magazines ceased for five years.

The extent of Hubbard’s popularity among the readers of Astounding and Unknown in the first few years of Campbell’s Golden Age was enormous. No better proof of that can be provided than a letter from a young reader that was published in the April, 1940 issue of Unknown, listing his ten favorite stories of 1939. Three of them—“The Ultimate Adventure,” “Ghoul” and “Slaves of Sleep”—were by L. Ron Hubbard. (The young reader’s name was Isaac Asimov, who would soon be one of Campbell’s Golden Age stalwarts himself.) So when Hubbard finally returned to the pages ofAstounding in the August, 1947 issue with a grim three-part novel of the postwar atomic-age world, “The End Is Not Yet,” reader response was enthusiastic.

But there was more to Hubbard’s return than the readers of that season suspected. Even while “The End Is Not Yet” was still being serialized, Campbell began to offer them the start of another major Hubbard enterprise—the first of a series of high-spirited space adventures under the pseudonym of Rene Lafayette. Entitled “Ole Doc Methuselah,” it appeared—without any of Campbell’s customary advance build-up—as the lead story of the October, 1947 Astounding, which also carried the final segment of the Hubbard novel.

The “Lafayette” pseudonym was not new. Hubbard had used it at least once before, in the April, 1940 issue of Unknown, on a short novel called “The Indigestible Triton.” The name was simply a variation on Hubbard’s own—(the “L.” in “L. Ron Hubbard” stands for “Lafayette”)—and almost certainly was used on “The Indigestible Triton” because of the extraordinary number of Hubbard stories that had been appearing in Campbell’s magazines in 1940: editors often get uneasy when one writer appears to be too prolific. Very likely the pseudonym was revived for “Ole Doc Methuselah” for much the same reason. With “The End Is Not Yet” already running in Astounding, Campbell would not have wanted to use the same author’s byline twice in the same issue.

“Ole Doc Methuselah”—the first of the seven galactic exploits in the book you are now holding—is an entertaining adventure hearkening back to Hubbard’s other genre writing—perhaps reminiscent of one of his classic westerns: The glamorous, mysterious young doctor and his comic but highly effective sidekick come riding into town to set things straight. The bad guys have set up a phony land-development scheme, saying that the railway will be coming through soon and everybody in town will get rich. But of course it’s a swindle, and it will be up to the young doctor and his buddy to defeat the villains and set everything to rights.

The readers loved it. “The Analytical Laboratory,” the reader-response poll that Campbell published every month, reported in the January, 1948 Astounding that it had been the most popular story in the October issue. (The conclusion of Hubbard’s “The End Is Not Yet” serial finished in second place.) Campbell himself noted, in commenting on the results, that he personally would classify the story “as fun rather than cerebral science fiction—and its position [in the poll] testifies that any type of science-fiction, well done, will take a first place!”

Cartier’s lively, boldly outlined drawings provided images of Doc and his alien slave Hippocrates as definitive as those that Tenniel did for Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland,” and gave the reader a cue not to take the story too seriously. Everyone knew right away that Ole Doc was a high-spirited romp—Campbell and Hubbard in an unbuttoned mood, sharing some fun with their readers for some great entertainment.

Cartier, who illustrated more stories by Hubbard than anyone else, has written fondly of his association with Hubbard’s work and with “Ole Doc Methuselah” in particular. “Illustrating Ron’s tales was a welcome assignment,” he said, “because they always contained scenes or incidents I found easy to picture. With some writers’ work I puzzled for hours on what to draw and I sometimes had to contact Campbell for an idea. That never happened with a Hubbard story. His plots allowed my imagination to run wild and the ideas for my illustrations would quickly come to mind.… It was Ole Doc’s adventures that many people, including myself, recall most fondly. Readers like my depiction of Hippocrates and I always enjoyed drawing the little, antennaed, four-armed creature. Oddly enough, in 1952 my wife, Gina, found a large five-legged frog in our yard.… Needless to say, the mutant frog was instantly dubbed Hippocrates or Pocrates, for short. He resided with honor in a garden pool and was featured in many local newspaper articles. The frog’s existence was as if Ron’s writings and my illustrations had come to life to prove that science fiction’s imaginative ideas are quite within the realm of possibility.”

A month after his debut, Ole Doc Methuselah returned, with “The Expensive Slaves“ in the November, 1947 issue. Again praised in the letter column of “The Analytical Laboratory,” there was no question that the series had been successfully launched, and the readers of the era—I was one—looked forward eagerly to the next episode.

They didn’t have long to wait. Doc was back in the March, 1948 issue with “Her Majesty’s Aberration.” The fourth in the series—“The Great Air Monopoly”—appeared in September, 1948. The April, 1949 issue brought “Plague,” a long lead story which gave the series its first display on Astounding’s cover. Two months later came “A Sound Investment.” (Campbell, announcing that story in the previous issue, commented, “This is one series in which the continuing hero is frankly and directly labeled as being deathless, incidentally; you won’t often find an author admitting that.” January, 1950 saw publication of “Ole Mother Methuselah,” the seventh of the Ole Doc Methuselah series.

And there the series ended. Hubbard had other projects of a whole new scope. In the May, 1950 Astounding Campbell published Hubbard’s non-fiction essay, “Dianetics, the Evolution of a Science,” and shortly afterward came Hubbard’s book, Dianetics,TheModernScienceofMentalHealth. It would be many years before Hubbard would write science fiction again.

Ole Doc Methuselah—the seven stories collected here is Hubbard’s most genial book. We see amiably miraculous events described in broad, vigorous strokes. Ole Doc, in three hours of deft plastic surgery, undoes an entrenched tyranny and restores an entire world’s social balance. Space pirates, land barons, vindictive Graustarkian queens, sinister magnates who make air a marketable commodity—nothing is too wild, too implausible, for the protean Hubbard. The immortal (but human and sometimes fallible) superhero and his wry, nagging alien pal are plainly destined to succeed in everything they attempt, and the key question is not if but how they will undo the villain and repair the damage that he has done.

That having been said, though, it would be a mistake to minimize these seven stories as light literature turned out by a great science-fiction writer in a casual mood. They have their roots in pulp-magazine techniques, but so did nearly everything that Campbell published in that era. In a time before network television and paperback books, the pulp magazines were the primary source of entertainment for millions of readers, and the best pulp writers were masters of the art of narrative.

The action in the Methuselah stories is fast and flamboyant and the inventiveness breathless and hectic. The mind of a shrewd and skilled storyteller can be observed at work on every page, and the stories grow richer and deeper as the series progresses—note, particularly, the touching moment in “The Great Air Monopoly” when Doc enters Hippocrates’s working quarters aboard their ship. (“A bowl of gooey gypsum and mustard, the slave’s favorite concoction for himself, stood half eaten on the sink, spoon drifting minutely from an upright position to the edge of the bowl as the neglected mixture hardened. A small, pink-bellied god grinned forlornly in a niche, gazing at the half-finished page of a letter to some outlandish world.… Ole Doc closed the galley softly as though he had been intruding on a private life and stood outside, hand still on the latch. For a long, long time he had never thought about it. But life without Hippocrates would be a desperate hard thing to bear.”) And though a lot of Doc’s medicinal techniques look more like magic to us, I remind you of Arthur C. Clarke’s famous dictum that the farther we peer into the future, the more closely science will seem to us to resemble magic. Ole Doc is nine hundred years old—he took his medical degree from Johns Hopkins in 1946—and looks about twenty-five; but who is to say that people now living will not survive to range the starways nine hundred years from now? It may not be likely, but it’s at least conceivable—and fun to think about.

The stories are good-natured entertainment; and they give us something to think about. As Alva Rogers pointed out in A Requiem for Astounding, his classic history of John Campbell’s great magazine, “The ‘Ole Doc Methuselah’ stories were immensely enjoyable; there was nothing pretentious about them, they were full of rousing action, colorful characters, spiced with wit, and yet, underneath it all, had some serious speculative ideas about one possible course organized medicine might take in the future and a picture of medical advances that was very intriguing.” They were well-loved stories in their day, rich with their sense of wonder; and here they are again, to delight, amuse and amaze a new readership now.

—Robert Silverberg

Award-winning author, Robert Silverberg, has written over 100 books and numerous short stories—and is equally renowned as a top editor of science fiction anthologies. —The Publisher

Preface

The Universal Medical Society—is the supreme council of physicians organized in the late Twenty-third century after the famous Revolt Caduceus which claimed the lives of two billion humanoids of the Earth-Arcton Empire through the villainous use of new medical discoveries to wage war and dominate entire countries. George Moulton, MD, Dr. Hubert Sands the physio-chemist, James J. Lufberry, MD, and Stephen Thomas Metridge, MD, who was later to become as well known as Ole Doc Methuselah, had for nearly a hundred years kept to a laboratory studying far beyond contemporary skills and incidentally extending their work by extending their own lives, came out of retirement, issued a pronunciamento—backed with atomic and du-ray hand weapons and a thousand counter-toxins—which denied to the casual practitioner all specialized medical secrets. Thus peace came to the Empire. Other systems anxiously clamored for similar aid and other great names of medicine quietly joined them. For centuries, as the Universal Medical Society, these men, hiding great names under nicknames, who eventually became a fixed seven hundred number, maintained a Center and by casual patrol of the Systems kept medicine as well as disease within rational bounds. Saluting no government, collecting no fees, permitting no infringement, the UMS became dreaded and revered as The Soldiers of Light and under the symbol of the crossed ray rods impinged their will upon the governments of space under a code of their own more rigorous than any code of laws. For the detailed records and history of the UMS, for conditions governing the hundred-year apprenticeship all future members must serve and for the special codes of call and appeal to the UMS in case of plague or disaster, consult L. Ron Hubbard’s “Conquest of Space,” 29th Volume, Chapter XCLII.

—Rene LaFayette

Ole Doc Methuselah

Chapter One

Ole Doc Methuselah wasn’t thinking what he was doing or he never would have landed on Spico that tempestuous afternoon. He had been working out some new formulas for cellular radiation—in his head as usual, he never could find his log tables—and the act of also navigating his rocket ship must have been an unconscious too much for him. He saw the asteroid planet, de-translated his speed and landed.

He sat there for some time at the controls, gazing out into the pleasant meadow and at the brook which wandered so invitingly upon it, and finishing up his tabulations.

When he had written down the answer on his gauntlet cuff—his filing system was full of torn scraps of cuffs—he felt very pleased with himself. He had mostly forgotten where he had been going, but he was going to pour the pile to her when his eye focused upon the brook. Ole Doc took his finger off the booster switch and grinned.

“That sure is green grass,” he said with a pleased sigh. And then he looked up over the control panels where he hung his fishing rod.

Lord knows what would have happened to Junction City if Ole Doc hadn’t decided to go fishing that day.

Seated on the lower step of the port ladder, Hippocrates patiently watched his god toss flies into the water with a deft and expert hand. Hippocrates was a sort of cross between several things. Ole Doc had picked him up cheap at an auction on Zeno just after the Trans-System War. At the time he had meant to discover some things about his purchase, such as his metabolism and why he dieted solely on gypsum, but that had been thirty years ago and Hippocrates had been an easy habit to acquire. Unpigmented, four-handed and silent as space itself, Hippocrates had set himself the scattered task of remembering all the things Ole Doc always forgot. He sat now, remembering—particularly that Ole Doc had some of his own medicine to take at thirty-six o’clock—and he might have sat there that way for hours and hours, phonograph-recordwise, if a radiating pellet hadn’t come with a sharp zip past his left antenna to land with a clang on the Morgue’s thick hull.

ZIP!CLANG!

Page forty-nine of the TalesoftheEarlySpacePioneers went smoothly into operation in Hippocrates’s gifted if unimaginative skull, which page translated itself into unruffled action.

He went inside and threw on Force Field Beta minus the Nine Hundred and Sixtieth Degree Arc, that being where Ole Doc was. Seeing that his worshiped master went on fishing, either unwitting or uncaring, Hippocrates then served out blasters and twenty rounds to himself and went back to sit on the bottom step of the port ladder.

The big spaceship—dented a bit, but lovely—simmered quietly in Procyon’s inviting light and the brook rippled and Ole Doc kept casting for whatever outrageous kind of fish he might find in that stream. This went on for an hour and then two things happened. Ole Doc, unaware of the force field, cast into it and got his fly back into his hat and a young woman came stumbling, panic-stricken, across the meadow toward the Morgue.

From amongst the stalks of flowers some forty feet high emerged an Earthman, thick and dark, wearing the remains of a uniform to which had been added civil space garb. He rushed forward a dozen meters before he paused in stride at the apparition of the huge golden ship with its emblazoned crossed ray rods of pharmacy. Then he saw Ole Doc fishing and the pursuer thrust a helmet up from a contemptuous grin.

It was nearer to Ole Doc than to the ship, and the girl, exhausted and disarrayed, stumbled toward him. The Earthman swept wide and put Ole Doc exactly between himself and the ladder before he came in.

Hippocrates turned from page forty-nine to page one hundred and fifteen. He leaped nimbly up to the top of the ship in the hope of shooting the Earthman on an angle which would miss Ole Doc. But he had no more than arrived and sighted before it became apparent to him that he would also now shoot the girl. This puzzled him. Obviously the girl was not an enemy who would harm Ole Doc. But the Earthman was. Still, it was better to blast girl and Earthman than to see Ole Doc harmed in any cause. The effort at recalling an exact instance made Hippocrates tremble and in that tremble Ole Doc also came into his fire field.

Having no warnings whatever, Ole Doc had just looked up from disentangling his hook from first his shirt and then his thumb and beheld two humans cannonading down upon him.

The adrenalized condition of the woman was due to the Earthman, that was clear. The Earthman was obviously a blast-for-hire from some tough astral slum and he had recently had a fight, for two knuckles bled. The girl threw herself in a collapse at Ole Doc’s feet and the Earthman came within a fatal fifteen feet.

Ole Doc twitched his wrist and put his big-hooked fly into the upper lip of the Earthman. This disappointed Ole Doc a little for he had been trying for the nose. The beggar was less hypothyroid than he had first estimated.

Pulling his game-fish bellowing into the stream, Ole Doc disarmed him and let him have a ray barrel just back of the medulla oblongata—which took care of the fellow nicely.

Hippocrates lowered himself with disappointed grunts down to the ladder. At his master’s hand signal he came forth with two needles, filled, sterilized and awaiting only a touch to break their seals and become useful.

Into the gluteal muscle—through clothes and all, because of sterilizing radiation of the point—Ole Doc gave the Earthman the contents of needle one. At the jab the fellow had squirmed a little and the doctor lifted one eyelid.

“You are a stone!” said Ole Doc. “You can’t move.”

The Earthman lay motionless, wide-eyed, being a stone. Hippocrates carefully noted the time with the fact in order to remind his master to let the fellow stop being a stone sometime. But in noting the time, Hippocrates found that it was six minutes to thirty-six o’clock and therefore time for a much more important thing—Ole Doc’s own medicine.

Brusquely, Hippocrates grabbed up the unconscious girl and waded back across the stream with her. The girl could wait. Thirty-six o’clock was thirty-six o’clock.

“Hold up!” said Ole Doc, needle poised.

Hippocrates grunted and kept on walking. He went directly into the main operating room of the Morgue and there amidst the cleverly jammed hotchpotch of trays and ray tubes, drawers, masks, retorts and reflectors, he unceremoniously dropped the girl. Monominded now, for this concerned his master—and where the rest of the world could go if it interfered with his master was a thing best expressed in silence—Hippocrates laid out the serum and the proper rays.

Humbly enough, the master bared his arm and then exposed himself—as a man does before a fireplace on a cold day—to the pouring out of life from the fixed tubes. It took only five minutes. It had to be done every five days.

Satisfied now, Hippocrates boosted the girl into a proper position for medication on the center table and adjusted a lamp or two fussily, while admiring his master’s touch with the needle.

Ole Doc was smiling, smiling with a strange poignancy. She was a very pretty girl, neatly made, small waisted, high breasted. Her tumbling crown of hair was like an avalanche of fire in the operating lights. Her lips were very soft, likely to be yielding to—

“Father!” she screamed in sudden consciousness. “Father!”

Ole Doc looked perplexed, offended. But then he saw that she did not know where she was. Her wild glare speared both master and thing.

“Where is my father?”

“We don’t rightly know, ma’am,” said Ole Doc. “You just—”

“He’s out there. They shot our ship down. He’s dying or dead! Help him!”

Hippocrates looked at master and master nodded. And when the servant left the ship it was with a bound so swift that it rocked the Morgue a little. He was only a meter tall, was Hippocrates, but he weighed nearly five hundred kilos.

Behind him came Ole Doc, but their speeds were so much at variance that before the physician could reach the tall flowers, Hippocrates was back through them carrying a man stretched out on a compartment door wrenched from its strong hinges for the purpose. That was page eight of FirstAidinSpace, not to wrestle people around but to put them on flat things. Man and door weighed nearly as much as Hippocrates but he wanted no help.

“‘Lung burns,”’ said Hippocrates, “‘are very difficult to heal and most usually result in death. When the heart is also damaged, particular care should be taken to move the patient as little as possible since exertion.…”’

Ole Doc listened to, without heeding, the high, squeaky singsong. Walking beside the girl’s father, Ole Doc was not so sure.

He felt a twinge of pity for the old man. He was proud of face, her father, gray of hair and very high and noble of brow. He was a big man, the kind of a man who would think big thoughts and fight and die for ideals.

The doctor beheld the seared stains, the charred fabric, the blasted flesh which now composed the all of the man’s chest. The bloody and gruesome scene was not a thing for a young girl’s eyes, even under disinterested circumstances—and a hypo would only do so much.

He stepped to the port and waved a hand back to the main salon. There was a professional imperiousness about it which thrust her along with invisible force. Out of her sight now, Ole Doc allowed Hippocrates to place the body on the multi-trayed operating table.

Under the gruesome flicker of ultraviolet, the wounded man looked even nearer death. The meters on the wall counted respiration and pulse and hemoglobin and all needles hovered in red while the big dial, with exaggerated and inexorable calm, swept solemnly down toward black.

“He’ll be dead in ten minutes,” said Ole Doc. He looked at the face, the high forehead, the brave contours. “He’ll be dead and the breed is gone enough to seed.”

At the panel, the doctor threw six switches and a great arc began to glow and snap like a hungry beast amid the batteries of tubes. A dynamo whined to a muted scream and then another began to growl. Ozone and brimstone bit the nostrils. The table was pooled in smoky light.

The injured man’s clothing vanished and, with small tinks, bits of metal dropped against the floor—coins, buckles, shoe nails.

Ole Doc tripped another line of switches and a third motor commenced to yell. The light about the table graduated from blue up to unseen black. The great hole in the charred chest began to glow whitely. The beating heart which had been laid bare by the original weapon slowed, slowed, slowed.

With a final twitch of his wrist, Ole Doc cut out the first stages and made his gesture to Hippocrates. That one lifted off the top tray which bore the man and, holding it balanced with one hand, opened a gravelike vault. There were long green tubes glowing in the vault and the feel of swirling gases. Hippocrates slid the tray along the grooves and clanged the door upon it.

Ole Doc stood at the board for a while, leaning a little against the force field which protected him from stray or glancing rays, and then sighing a weary sigh, evened the glittering line. Normal light and air came back into the operating room and the salon door slid automatically open.

The girl stood there, tense question in her every line, fear digging nails into palms.

Ole Doc put on a professional smile. “There is a very fair chance that we may save him, Miss—”

“Elston.”

“A very fair chance. Fifty-fifty.”

“But what are you doing now?” she demanded.

Ole Doc would ordinarily have given a rough time to anyone else who had dared to ask him that. But he felt somehow summery as he gazed at her.

“All I can, Miss Elston.”

“Then he’ll soon be well?”

“Why … ah … that depends. You see, well …” How was he going to tell her that what he virtually needed was a whole new man? And how could he explain that professional ethics required one to forgo the expedience of kidnapping, no matter how vital it might seem? For what does one do with a heart split in two and a lung torn open wide when they are filled with foreign matter and ever-burning rays unless it is to get a new chest entire?

“We’ll have to try,” he said. “He’ll be all right for now … for a month, or more perhaps. He is in no pain, will have no memory of this and if he is ever cured, will be cured entirely. The devil of it is, Miss Elston, men always advance their weapons about a thousand years ahead of medical science. But then, we’ll try. We’ll try.”

And the way she looked at him then made it summer entirely. “Even …” she said hesitantly, “even if you are so young, I have all the confidence in the universe in you, Doctor.”

That startled Ole Doc. He hadn’t been patronized that way for a long, long time. But more important—he glanced into the mirror over the table. He looked more closely. Well, he did look young. Thirty, maybe. And a glow began to creep up over him, and as he looked back to her and saw her cascading glory of hair and the sweetness of her face—

“Master Doctor!” interrupted the unwelcome Hippocrates. “The Earthman is gone.”

Ole Doc stared out the port and saw thin twirls of smoke arising from the charred and blasted grass. The Earthman was gone all right, and very much gone for good. But one boot remained.

“Looks,” said Ole Doc, “like we’ve got some opposition.”

Chapter Two

“We were proceeding to Junction City,” said the girl, “when a group of men shot down our ship and attacked us.”

Ole Doc picked a thoughtful tooth, for the fish he had caught had been excellent—deep fried, southern style. He felt benign, chivalrous. Summer was in full bloom. He was thinking harder about her hair than about her narrative. Robbery and banditry on the spaceways were not new, particularly on such a little-inhabited planet as Spico, but the thoughts which visited him had not been found in his mind for a long, long time. She made a throne room of the tiny dining salon and Ole Doc harked back to lonely days in cold space, on hostile and uninviting planets, and the woman-hunger which comes.

“Did you see any of them?” he asked, only to hear her voice again.

“I didn’t need to,” she said.

The tone she took startled Ole Doc. Had he been regarding this from the viewpoint of volume sixteen of Klote’s standard work on human psychology, he would have realized the predicament into which, with those words, he had launched himself. Thirteen hundred years ago a chap named Malory had written a book about knight-errantry; it had unhappily faded from Ole Doc’s mind.

“Miss Elston,” he said, “if you know the identity of the band then perhaps something can be done, although I do not see what you could possibly gain merely by bringing them to the Bar of the Space Council.”

Hippocrates was lumbering back and forth at the buffet clearing away the remains of the meal. He was quoting singsong under his breath the code of the Soldiers of Light, “It shall be unlawful for any medical officer to engage in political activities of any kind, to involve himself with law, or in short, aid or abet the causes, petty feuds, personal vengeances …’” Ole Doc did not hear him. The music of Venus was in Miss Elston’s voice.

“Why, I told you about the box, Doctor, it contains the deed to this planet and, more important than that, it has the letter which my father was bringing here to restrain his partner from selling off parcels of land at Junction City. Oh, Doctor, can’t you understand how cruel it is to these people? More than ten thousand of them have come here with all the savings they have in the universe to buy land in the hope that they can profit by its resale to the Procyon-Sirius Spaceways.

“When my father, Judge Elston, first became interested in this scheme it was because it had been brought to his attention by a Captain Blanchard who came to us at our home near New York and told us that he had private information that Spico was completely necessary to the Procyon-Sirius Spaceways as a stopover point and that it would be of immense value. Nobody knew, except some officials in the company, according to Captain Blanchard, and my father was led to believe that Captain Blanchard had an excellent reputation and that the information was entirely correct.

“Blanchard came here on Spico some time ago and laid out the necessary landing fields and subdivided Junction City, using my father’s name and money. He circulated illustrated folders everywhere setting forth the opportunities of business and making the statement that the Spaceways would shortly begin their own installation. Thousands and thousands of people came here in the hope either of settling and beginning a new life or of profiting in the boom which would result. Blanchard sold them land still using my father’s name.

“A short while ago my father learned from officials of the company that a landing field was not necessary here due to a new type of propulsion motor which made a stopover unnecessary. He learned also that Captain Blanchard had been involved in blue-sky speculations on Alpha Centauri. He visiographed Blanchard and told him to cease all operations immediately and to refund all money, saying that he, Judge Elston, would absorb any loss occasioned in the matter. Blanchard told him that it was a good scheme and was making money and that he didn’t intend to refund a dime of it. He also said that if my father didn’t want himself exposed as a crook, he would have to stay out of it. Blanchard reminded him that only the name of Elston appeared on all literature and deeds and that the entire scheme had obviously been conceived by my father. Then he threatened to kill my father and we have been unable to get in contact with him since.

“I begged my father to expose Blanchard to the Upper Council but he said he would have to wash his own dirty linen. Immediately afterwards we came up here. He tried to leave me behind but I was terrified that something would happen to him and so I would not stay home.

“My father had the proof that the Procyon-Sirius Spaceways would not build their field here. It was in that box. Blanchard has kept good his threat. He attacked us, he stole the evidence, and now—” She began to sob suddenly at the thought of her father lying there in that harshly glittering room so close to death. Hippocrates phonograph-recordwise was beginning the code all over again. “‘It shall be unlawful for any medical officer to engage in political activities of any kind, to involve himself with law, or in short, aid or abet the causes, petty feuds, personal vengeances …’”

But Ole Doc’s eyes were on her hair and his mind was roaming back to other days. Almost absently he dropped a minute capsule in her water glass and told her to drink it. Soon she was more composed.

“Even if you could save my father’s life, Doctor,” she said, “it wouldn’t do any good. The shock of this scandal would kill him.”

Ole Doc hummed absently and put his hands behind his head. His black silk dressing gown rustled. His youthful eyes drifted inwards. He thrust his furred boots out before him. The humming stopped. He sat up. His fine surgeon’s hands doubled into fists and with twin blows upon the table he propelled himself to his feet.

“Why, there is nothing more simple than this. All we have to do is find this Blanchard, take the evidence away from him, tell the people that they’ve been swindled, give them back their money, put your father on his feet and everything will be all right. The entire mess will be straightened out in jig time.” He beamed fondly upon her. And then, with an air of aplomb, began to pour fresh wine. He had half filled the second glass when abrupt realization startled him so that he spilled a great gout of wine where it lay like a puddle of blood on the snowy cloth.

But across from him sat his ladye faire and now that he had couched his lance and found himself face to face with an enemy, even the thought of the shattered and blackened remains of the Earthman did not drive him back. He smiled reassuringly and patted her hand.

Her eyes were jewels in the amber light.

Chapter Three

Junction Citywas all turmoil, dust and hope. There were men there who had made a thousand dollars yesterday, who had made two thousand dollars this morning, and who avidly dreamed of making five thousand before night. Lots were being bought and sold with such giddy rapidity that no one could keep trace of their value. Several battered tramp spaceships which had brought pioneers and their effects lay about the spaceport. Rumors, all of them confident, all of them concerning profit, banged about the streets like bullets.

Smug, hard and ruthless, Edouard Blanchard sat under the awning of the Comet Saloon. His agate eyes were fixed upon a newly arrived ship, a gold-colored ship with crossed ray rods upon her nose. He looked up and down the crowded dusty street where spaceboot trod on leather brogan and placesilk rustled on denim. Men and women from a hundred planets were there. Men of hundreds of races and creeds were there with pasts as checkerboard as history itself, yet bound together by a common anxiety to profit and build a world anew.

It mattered nothing to Edouard Blanchard that bubbles left human wreckage in their wake, that on his departure all available buying power for this planet would go as well. Ten thousand homely souls, whose only crime had been hope, would be consigned to grubbing without finance, tools or imported food for a questionable living on a small orb bound on a forgotten track in space. Such concerns rarely trouble the consciences of the Edouard Blanchards.

The agate eyes fastened upon an ambling Martian named Dart, who with his mask to take out forty percent of the oxygen from this atmosphere and so permit him to breathe, looked like some badly conceived and infinitely evil gnome.

“Dart,” said Blanchard, “take a run over to that medical ship and find out what a Soldier of Light is doing in a place like this.”

The Martian fumbled with his mask and then uneasily hefted his blaster belt. He squirmed and wriggled as though some communication of great importance had met a dam halfway up to the surface. Blanchard stared at him. “Well? Go! What are you waiting for?”

Dart squirmed until a small red haze of dust stood about his boots. “I’ve always been faithful to you, Captain. I ain’t never sold you out to nobody. I’m honest, that’s what I am.” His dishonest eyes wriggled upwards until they reached the level of Blanchard’s collar.

Blanchard came upright. There was a sadistic stir in his hands. Under this compulsion Dart wilted and his voice from a vicious whine changed to a monotonous wail. “That was the ship Miss Elston ran to. I’m an honest man and I ain’t going to tell you no different.”

“But you said she escaped and I’ve had twelve men searching for her for the past day. Damn you, Dart. Why couldn’t you have told me this?”

“I just thought she’d fly away and that would be all there was to it. I didn’t think she’d come back. But you ain’t got nothing to be afeared of, Mr. Captain Blanchard. No Soldier of Light can monkey with politics. The Universal Medical Society won’t interfere.”

Captain Blanchard’s hands, long, thin, twisted anew as though they were wrapping themselves around the sinews in Dart’s body and snapping them out one by one. He restrained the motion and sank back. “You know I’m your friend, Dart. You know I wouldn’t do anything to hurt you. You know it’s only those who oppose my will whom I, shall I say, remove. You know that you are safe enough.”

“Oh yes, Captain Blanchard, I know you are my friend. I appreciate it. You don’t know how I appreciate it. I’m an honest man and I don’t mind saying so.”

“And you’ll always be honest, won’t you, Dart?” said Blanchard, white hands twitching. He smiled. From a deep pocket he extracted first a long knife with which he regularly pared his nails, then a thick sheaf of money, and finally, amongst several deeds, a communication which Mr. Elston had been attempting to bring to Spico. He read it through in all its damning certainty. It said that the Procyon-Sirius Spaceways would not use this planet. Then, striking a match to light a cigar, he touched it to the document and idly watched it burn. The last flaming fragment was suddenly hurled at the Martian.

“Get over there instantly,” said Blanchard, “and find out what you can. If Miss Elston comes away from that ship unattended, see that she never goes back to it. And make very certain, my honest friend, that the Soldier on that ship doesn’t find out anything.”

But before Dart had more than beaten out the fire on the skirt of his coat, a youthful, pleasant voice addressed them. Blanchard hastily smoothed out his hands, veiled his eyes, and with a smile which he supposed to be winning faced the speaker.

Ole Doc, having given them his “good morning,” continued guilelessly as though he had not heard a thing.

“My, what a beautiful prospect you have here. If I could only find the man who sells the lots—”

Blanchard stood up instantly and grasped Ole Doc Methuselah by the hand, which he pumped with enormous enthusiasm. “Well, you’ve come to the right place, stranger. I am Captain Blanchard and very pleased to make your acquaintance, Mr.—”

“Oh, Captain Blanchard, I have heard a great deal about you,” said Ole Doc, his blue eyes very innocent. “It is a wonderful thing you are doing here. Making all these people rich and happy.”

“Oh, not my doing, I assure you,” said Captain Blanchard. “This project was started by a Mr. Elston of New York City, Earth. I am but his agent trying in my small way to carry out his orders.” He freed his hand and swept it to take in the dreary, dusty and being-cluttered prospect. “Happy, happy people,” he said. “Oh, you don’t know what pleasure it gives me to see little homes being created and small families being placed in the way of great riches. You don’t know.” Very affectedly he gazed down at the dirt as though to let his tears of happiness splash into it undetected. However, no tears splashed.

After a little he recovered himself enough to say, “We have only two lots left and they are a thousand dollars apiece.”

Ole Doc promptly dragged two bills from his breast pocket and handed them over. If he was surprised at this swift method of doing business, Captain Blanchard managed to again master his emotion. He quickly escorted Ole Doc to the clapboard shack which served as the city hall so that the deeds could be properly recorded.

As they entered the flimsy structure a tall, prepossessing individual stopped Blanchard and held him in momentary converse concerning a program to put schools into effect. Ole Doc, eyeing the man, estimated him as idealistic but stupid. He was not particularly surprised when Blanchard introduced him as Mr. Zoran, the mayor of Junction City.

Here, thought Ole Doc, is the fall guy when Blanchard clears out.

“I’m very glad to make your acquaintance Mr.…” said Mayor Zoran.

“And I yours,” said Ole Doc. “It must be quite an honor to have ten thousand people so completely dependent upon your judgment.”

Mayor Zoran swelled slightly. “I find it a heavy but honorable trust, sir. There is nothing I would not do for our good citizens. You may talk of empire builders, sir, but in the future you cannot omit mention of these fine beings who make up our population in Junction City. We have kept the riffraff to a minimum, sir. We are families, husbands, wives, small children. We are determined, sir, to make this an Eden.” He nodded at this happy thought, smiled. “To make this an Eden wherein we all may prosper, for with the revenue of the Spaceways flooding through our town, and with our own work in the fields to raise its supplies, and with the payroll of the atomic plant which Captain Blanchard assures us will begin to be built within a month, we may look forward to long, happy and prosperous lives.”

Ole Doc looked across the bleak plain. A two-year winter would come to Spico soon, a winter in which no food could be raised. He looked at Mayor Zoran. “I trust, sir, that you have reserved some of your capital against possible emergencies, emergencies such as food, or the cost of relief expeditions coming here.”

Captain Blanchard masked a startled gleam which had leaped into his agate eyes. “I am sure that there is no need for that,” he said.

Mayor Zoran’s head shook away any thought of such a need. “If land and building materials have been expensive,” he said, “I am sure there will be more money in the community as soon as the Spaceways representatives arrive, and there is enough food now for three weeks. By the way,” he said, turning to Blanchard, “didn’t you tell me that today was the day the officials would come here?”

Blanchard caught and hid his hands. “Why, my dear mayor,” he said, “there are always slight delays. These big companies, you know, officials with many things on their minds, today, tomorrow, undoubtedly sometime this week.”