11,14 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

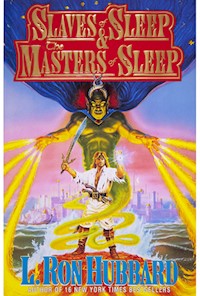

Jan Palmer has everything—except happiness. He wishes to escape to another world. But be careful what you wish for.... Waking out of a deep sleep, he escapes—into a living nightmare. In a realm of deadly secrets and dangerous dancing girls, he discovers that humankind’s fate lies in his hands. Abounding in revelation, this is a tale that might just open your eyes. “I stayed up all night finishing it. The yarn scintillated.” —Ray Bradbury

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 527

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1993

Ähnliche

Selected fiction works by L. Ron Hubbard

FANTASY

If I Were You

Slaves of Sleep & The Masters of Sleep

Typewriter in the Sky

SCIENCE FICTION

Battlefield Earth

Final Blackout

The Great Secret

The Kingslayer

The Mission Earth Dekalogy:*

Volume 1: The Invaders Plan

Volume 2: Black Genesis

Volume 3: The Enemy Within

Volume 4: An Alien Affair

Volume 5: Fortune of Fear

Volume 6: Death Quest

Volume 7: Voyage of Vengeance

Volume 8: Disaster

Volume 9: Villainy Victorious

Volume 10: The Doomed Planet

Ole Doc Methuselah

To the Stars

HISTORICAL FICTION

Buckskin Brigades

Under the Black Ensign

MYSTERY

Cargo of Coffins

Dead Men Kill

Spy Killer

WESTERN

Branded Outlaw

Six-Gun Caballero

A full list of L. Ron Hubbard’s fiction works can be found at GalaxyPress.com

*Dekalogy—a group of ten volumes

Thank you for purchasingSlaves of Sleep & The Masters of Sleep by L. Ron Hubbard.

To receive special offers, bonus content and info on new fiction releases by L. Ron Hubbard, sign up for the Galaxy Press newsletter.

Visit us online at GalaxyPress.com

SLAVES OF SLEEP & THE MASTERS OF SLEEP

© 1993 L. Ron Hubbard Library. All Rights Reserved.

Any unauthorized copying, translation, duplication, importation or distribution, in whole or in part, by any means, including electronic copying, storage or transmission, is a violation of applicable laws.

Cover Art: Gerry GraceCover artwork: © 1993 L. Ron Hubbard Library. All Rights Reserved.

Mission Earth is a trademark owned by L. Ron Hubbard Library and is used with permission. Battlefield Earth is a trademark owned by Author Services, Inc. and is used with permission.

Print ISBN: 978-1-59212-218-9EPUB edition ISBN: 978-1-59212-615-6Kindle edition ISBN: 978-1-59212-088-8Audiobook ISBN: 978-1-59212-219-6

Published by Galaxy Press, Inc.7051 Hollywood Boulevard, Hollywood, California 90028

www.GalaxyPress.com

Contents

Publisher’s Note

Preface

Slaves of Sleep

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

The Masters of Sleep

Foreword

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

About the Author

Glossary

Publisher’s Note

This is the first time that L. Ron Hubbard’s fantasy novel, Slaves of Sleep and its sequel, The Masters of Sleep, have been published in a single volume. Though published years apart, both novels chronicle the adventures of Jan Palmer in the parallel worlds of Earth and the Land of the Jinn.

“Slaves of Sleep” was published originally in the July 1939 issue of Unknown—the most celebrated and respected fantasy magazine of its day. The long-awaited follow-up, “The Masters of Sleep” appeared in the October 1950 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

Fantasy was just one of the many genres in which Mr. Hubbard excelled during his long and productive career as a professional writer. During his lifetime, he wrote over 260 novels, novelettes, short stories, screenplays and dramatic works encompassing a wide variety of subjects.

He initially established his reputation as an author of fast-paced adventure, detective and western fiction. Later, he wrote innovative science fiction and fantasy stories that gave new directions to these genres and established him as one of the founders of the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

In 1980, in celebration of his 50th anniversary as a professional writer, L. Ron Hubbard returned to the genre of science fiction and completed one of the biggest and most popular science fiction novels ever written: Battlefield Earth. L. Ron Hubbard’s masterpiece of comic satire, the 1.2 million word Mission Earth dekalogy (a set of 10 books), was published between 1985 and 1987. Battlefield Earth and each volume of the Mission Earth series became New York Times and international bestsellers and continue to appear on bestseller lists throughout the world.

Galaxy Press is undertaking a publishing plan to rerelease all of L. Ron Hubbard’s classic works of fiction. A number of these, including Buckskin Brigades, Final Blackout, Fear and Ole Doc Methuselah have already been published, each with a companion audio edition.

—The Publisher

Preface

Aword … to the curious reader:

There are many persons in these skeptical times who affect to deride everything connected with the occult sciences, or black arts; who have no faith in the efficacy of conjurations, incantations or divinations; and who stoutly contend that such things never had existence. To such determined unbelievers, the testimony of the past ages is as nothing; they require the evidence of their own senses, and deny that such arts and practices have prevailed in days of yore, simply because they meet with no instances of them in the present day. They cannot perceive that, as the world became versed in the natural sciences, the supernatural became superfluous and fell into disuse; and that the hardy inventions of art superseded the mysteries of man. Still, say the enlightened few, those mystic powers exist, though in a latent state, and untasked by the ingenuity of man. A talisman is still a talisman, possessing all its indwelling and awful properties; though it may have lain dormant for ages at the bottom of the sea, or in the dusty cabinet of the antiquary. The signet of Solomon the Wise, for instance, is well known to have held potent control over genii, demons and enchantments; now who will positively assert that the same mystic signet, wherever it may exist, does not at the present moment possess the same marvelous virtues which distinguished it in olden time? Let those who doubt repair to Salamanca, delve into the cave of San Cyprian, explore its hidden secrets and decide. As to those who will not be at pains to make such investigation, let them substitute faith for incredulity and receive with honest credence the foregoing legend.

So pled Washington Irving for a tale of an enchanted soldier. And in no better words could the case for the following story be presented. As for the Seal of Sulayman,* look to Kirker’s Cabala Sarracenica. As for genii (or, more properly, Jinns, jinn or Jan), it is the root for our word “genius”, so widely are these spirits recognized. A very imperfect idea of the jinn is born of the insipid children’s translations of The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment, but in the original work (which is actually an Arabian history interspersed with legends) the subject is more competently treated. For the ardent researcher, Burton’s edition is recommended, though due to its being a forbidden work in these United States, it is very difficult to find. There is, however, a full set in the New York Public Library where the wise librarians have devoted an entire division to works dealing with the black arts.

Man is a very stubborn creature. He would rather confound himself with “laws” of his own invention than to fatalistically accept perhaps truer but infinitely simpler explanations as offered by the supernatural—though it is a travesty to so group the omnipresent jinn!

And so I commend you to your future nightmares.

L. Ron HubbardThe Pacific Northwest1939

*Sulayman (less properly, Solomon), who ruled in Jerusalem about 960 BC, has left his impression on almost every land but especially Persia, Arabia and, in general Africa, where dark tales may be found in moldy books which do not at all agree with the prosaic histories written in modern times. Lord of more than mere man, the treasures he amassed are still rumored to be hidden. His seal is still known in all lands where the black arts flourish and might be said to be the most universal of all magic symbols, probably because of the power Sulayman gained through the use of the original. It consists, properly, of two triangles upon one another to form a six-pointed star which in turn is surrounded by a circle representing fire. –L.R.H.

Slaves of Sleep

CHAPTER ONE

The Copper Jar

It was with a weary frown that Jan Palmer beheld Thompson standing there on the dock. Thompson, like some evil raven, never made his appearance unless to inform Jan in a somehow accusative way that business, after all, should supersede such silly trivialities as sailing. Jan was half-minded to put the flattie about and scud back across the wind-patterned Puget Sound; but he had already luffed up into the wind to carry in to the dock and Thompson had unbent enough to reach for the painter—more as an effort to detain Jan than to help him land.

Jan let go his jib and main halyards and guided the sail down into a restive bundle. He pretended not to notice Thompson, using nearsightedness as his usual excuse—for although nothing was actually wrong with his eyes, he found that glasses helped him in his uneasy maneuvers with mankind.

“The gentleman from the university is here to see you again, Mr. Palmer.” Thompson scowled his reproof for such treatment of a man of learning. Everybody but Jan Palmer impressed Thompson. “He has been waiting for more than two hours.”

“I wish,” said Jan, “I wish you’d tell such people you don’t know when I’ll be back.” He was taking slides from their track, though it was not really necessary for him to unbend his sail in such weather. “I haven’t anything to say to him.”

“He seems to think differently. It is a shame that you can’t realize the honor such people do you. If your father …”

“Do we have to go into that?” said Jan, fretfully. “I don’t like to have to talk to such people. They … they make me nervous.”

“Your father never had any such difficulties. I told him before he died that it was a mistake …”

“I know,” sighed Jan. “It was a mistake. But I didn’t ask to be his heir.”

“A healthy man rarely leaves a will when he is still young. And you, as his son, should at least have the courtesy to see people when they search you out. It has been a week since you were even near the offices.…”

“I’ve been busy,” defended Jan.

“Busy!” said Thompson, pulling his long nose as though to keep from laughing. He had found long, long ago, when Jan was hardly big enough to feed himself, that it was no difficult matter to bully the boy since there would never be any redress. “Busy with a sailboat when fifteen Alaskan liners are under your control. But you are still keeping the gentleman waiting.”

“I’m not going to see him,” said Jan in a tone of defiance which already admitted his defeat. “He has no real business with me. It is that model of the Arab dhow. He wants it and I can’t part with it and he’ll wheedle and fuss and …” He sat down on the coaming and put his face in his palms. “Oh, why,” he wept, “why can’t people leave me alone?”

“Your father would turn over in his grave if he heard that,” said the remorseless Thompson. “There isn’t any use of your sitting there like a spoiled child and wailing about people. This gentleman is a professor at the university and he has already looked for you for two hours. As long as you are a Palmer, people will continue to call on you. Now come along.”

Resentfully, well knowing he should slam this ancient bird of a secretary into his proper position, Jan followed up the path from the beach to the huge, garden-entrenched mansion.

Theoretically the place was his, all his. But that was only theoretically. Actually it was overlorded by a whiskered grandaunt whose already sharp temper had been whetted by the recent injustice of the probate court.

She was waiting now, inside the door, her dark dress stiff with disapproval, her needlepoint eyes sighted down her nose, ready to pick up the faint dampness of Jan’s footprints.

“Jan! Don’t you dare soak that rug with saltwater! Indeed! One would think you had been raised on a tide flat for all the regard you have for my efforts to give you a decent home. JAN! Don’t throw your cap on that table! What would a visitor think?”

“Yes, Aunt Ethel,” he replied with resignation. He wished he had nerve enough to say that the house was evidently run for no one but visitors. However, he supposed that he never would. He picked up his cap and gave the rug a wide berth and somehow navigated to the hall which led darkly to his study. At the end, at least, was a sanctuary. Whatever might be said to him in the rest of the house, his own apartment was his castle. The place, in the eyes of all but himself, was such a hideous mess that it dismayed the beholder.

In all truth the place was not really disorderly. It contained a very assorted lot of furniture which Jan, with his father’s indulgent permission, had salvaged from the turbulent and dusty seas of the attic. The Palmers, until now, had voyaged the world and the flotsam culled from many a strange beach had at last been cast up in these rooms. One donor in particular, a cousin who now rested in the deep off Madagascar, had had an eye for oddity, contributing the greater part of the assembled spears and headdresses as well as the truly beautiful blackwood desk all inlaid with pearl and ivory.

This was sanctuary and it irritated Jan to find that he had yet to rid himself of a human being before he could again find any peace.

Professor Frobish raised himself from his chair and bowed deferentially. But for his following stretch, it might have been supposed that he had been two whole hours on that cushion. Jan surveyed him without enthusiasm. Indeed there was only one human being in the world to whom Jan granted enthusiastic regard and she … well … that was wholly impossible. The professor was a vital sort of man, the very sort Jan distrusted the most. It would be impossible to talk such a man down.

“Mr. Palmer, I believe?” Jan winced at the pressure of the hand and quickly recovered his own. Nervously he wandered around the table and began to pack a pipe.

“Mr. Palmer, I am Professor Frobish, the Arabianologist at the university. I hope you will forgive my intrusion. Indeed, it shows doubtlessly great temerity on my part to so take up the time of one of Seattle’s most influential men.”

He wants something, Jan told himself. They all want something. He lighted the pipe so as to avoid looking straight at the fellow.

“It has come to our ears that you were fortunate enough to have delivered to you a model—if you’ll forgive me for coming to the point, but I know how valuable your time is. This model, I understand, was recovered from a Tunisian ruin and sent to your father.…”

He went on and on but Jan was not very attentive. Jan paced restively over to the wide windows and stood contemplating the azure waters backed by the rising green of hills and, finally, by the glory of the shining, snowcapped Olympics. He wished he had been sensible enough to stay out there. Next time he would take his cabin sloop and enough food to last a day or two—but at the same time, realizing the wrath this would bring down upon him, he knew that he would never do so. He turned, puffing hopelessly at his pipe, to watch the Arabianologist. Suddenly he was struck by the fact that though the man kept talking about and pointing to the model of the ancient dhow which stood upon the great blackwood desk, his interest did not lie there. On entering the room it might have, but now Frobish’s eye kept straying to the darkest corner of the room. What, Jan wondered, in all these trophies had excited this fervid man’s greed? Certainly the professor was having a difficult time staying on his subject and wasn’t making a very strong case of why the university should be presented with this valuable model.

Jan’s schooling, while not flattering to humanity, was nevertheless thorough. His father, too engrossed in shipping to give much time to raising a son, had failed wholly to notice that the household used the boy to bolster up their respective prides which they perforce must humble before the elder Palmer. And, as a Palmer, it would not be fitting to give the boy a common education; he had even been spared the solace of youthful companionship. And now, at twenty-seven, he was perfectly aware of the fact that men never did anything without thought of personal gain and that when men reacted strangely they would bear much watching. This professor wanted something besides this innocent dhow. Jan strolled around the room with seeming aimlessness. Finally, by devious routes, he arrived beside the corner which often caught Frobish’s eye. But there was no enlightenment here. The only thing present was a rack of Malay swords and a very old copper jar tightly sealed with lead. The krisses were too ordinary, therefore it must be the jar. But what, pray tell, could an Arabianologist discover in such a thing? Jan had to think hard—all the while with placid, even timid countenance—to recall the history of the jar.

“And so,” Frobish concluded, “you would be doing science a great favor by at least lending us this model. There is none other like it in existence and it would greatly further our knowledge of the seafaring of the ancient Arab.”

It had been in Jan’s mind to say no. But the fellow would stay and argue, he knew. Personally he had rather liked that little dhow with its strangely indestructible rigging.

“I guess you can have it,” he said.

Frobish had not expected such an easy victory. But even so he was not much elated. He told Jan he was a benefactor of science and put the model in its teak box and then, hesitantly, reached for his hat.

“Thank you so much,” he said again. “We’ll not be likely to forget this service.”

“That’s all right,” said Jan, wondering why he had given up so easily.

And still the professor lingered on small-talk excuses. At last he ran out of conversation and stood merely fumbling with his hat. Jan scented trouble. He did not know just how or why, but he did.

“This is a very interesting room,” said the professor, at last. “Your people must have traveled the Seven Seas a great deal. But then they would have, of course.” He gave his hat a hard twist. “Take … er … take that copper jar, for instance. A very interesting piece of work. Ancient Arab also, I presume.”

Jan nodded.

“Might I be out of order to ask you where it came from?”

Jan had been remembering and he had the answer ready. And though he suddenly didn’t want to talk about that copper jar he heard himself doing so.

“My father’s cousin, Greg Palmer, brought it back from the Mediterranean a long time before I was born. He was always bringing things home.”

“Interesting,” said Frobish. “Must have been quite a fellow.”

“Everybody said he wasn’t much good,” said Jan. He added ruefully, “I am supposed to be like him, they say. He never held any job for long but they say he could have been a millionaire a lot of times if he had tried. But he claimed money made a man put his roots down. That’s one thing he never did. That’s his picture on the wall there.”

Frobish inspected it out of policy. “Ah, so? Well, well, I must say that he does look a great deal like you—that is, without your glasses, of course.”

“He—” Jan almost said, “He’s the only friend I ever had,” but he swiftly changed it. “He was very good to me.”

“Did—ah—did he ever say anything about that copper jar?” Frobish could hardly restrain his eagerness.

“Yes,” said Jan flatly. “He did. He said it was given to him by a French seiner on the Tunisian coast.”

“Is that all?”

“And when he left it here Aunt Ethel told him it was a heathen thing and that he had to put it in the attic. I used to go up and look at it sometimes and I was pretty curious about it.”

“How is that?”

“He made me promise never to open it.”

“What? I mean—is that so?” Frobish paced over to it and bent down as though examining it for the first time. “I see that you never did. The seal is still firmly in place.”

“I might have if Greg hadn’t been killed but …”

“Ah, yes, I understand. Sentiment.” He stood up and sighed. “Well! I must be going. That’s a very fine piece of work and I compliment you on your possession of it. Well, good day.” But still he didn’t leave. He stood with one hand on the doorknob, looking back at the jar as a bird will return the stare of a snake. “Ah … er … have you ever had any curiosity about what it might contain?”

“Of course,” said Jan, “but until now I had almost forgotten about it. Ten years ago it was all I could do to keep from looking in it.”

“Perhaps you thought about jewels?”

“No … not exactly.”

Suddenly they both knew what the other was thinking about. But before they could put it into words there came a sharp rap on the door.

Without waiting for answer, a very officious little man bustled in. He stared hard at Jan and paid no attention whatever to the professor.

“I called three times,” he complained.

“I was out on the Sound,” said Jan, uneasily.

“There are some papers which have to have your signature,” snapped the fellow, throwing a briefcase up on the blackwood desk and pulling the documents out. It was very plain that he resented having to seek Jan out at all.

Jan moved to the desk and picked up a pen. He knew that as general manager of the Bering Sea Steamship Corporation Nathaniel Green had his troubles. And perhaps he had a perfect right to be resentful, having spent all his life in the service of the late Palmer and then having not one share of stock left to him.

“If I could have your power of attorney I wouldn’t have to come all the way out here ten and twenty times a day!” said Green. “I have ten thousand things to do and not half time enough to do them in and yet I have to play messenger boy.”

“I’m sorry,” said Jan.

“You might at least come down to the office.”

Jan shuddered. He had tried that, only to have Green browbeat him before clerks and to have dozens and dozens of people foisted off on him for interview.

Green swept the papers back into the briefcase and bustled off without another word as though the entire world of shipping was waiting on his return.

Frobish’s face was flushed. He had hardly noticed the character of the interrupter. Now he came to the jar and stood with one hand on it.

“Mr. Palmer, for many years I have been keenly interested in things which … well, which are not exactly open to scientific speculation. It is barely possible that here, under my hand, I have a clue to a problem I have long examined—perhaps I have the answer itself. You do not censure my excitement?”

“You have researched demonology?”

“As connected with the ancient Egyptians and Arabs. I see that we understand each other perfectly. If this was found in waters off Tunisia, then it is barely possible that it is one of THE copper jars. You know about them?”

“A little.”

“Very few people know much about the jinn. They seem to have vanished from the face of the earth several centuries ago, though there is every reason to suppose that they existed in historical times. Sulayman is said to have converted most of the jinn tribes to the faith of Mohammed after a considerable war. Sulayman was an actual king and those battles are a part of his court record. This, Mr. Palmer, is not a cupid’s bow on this stopper but the Seal of Sulayman!” Frobish was growing very excited. “When several tribes refused to acknowledge Mohammed as the prophet, Sulayman had them thrown into copper jars such as this, stoppered with his seal, and thrown into the sea off the coast of Tunis!”

“I know,” said Jan, quietly.

“You knew? And yet … yet you did not investigate?”

“I gave my word that I would not open that jar.”

“Your word. But think, man, what a revelation this would be! Who knows but what this actually contains one of those luckless ifrīts?”

Jan wandered back to his humidor and repacked his pipe. As far as he was concerned the interview was over. He might be bullied into anything but when it came to breaking his word … Carefully he lighted his pipe.

Frobish’s face was feverish. He was straining forward toward Jan, waiting for the acquiescence he felt certain must come. And when at last he found that his own enthusiasm had failed to kindle a return blaze, he threw out his hands in a despairing gesture and marched ahead, forcing Jan back against a chair into which he slumped. Frobish towered over him.

“You can’t be human!” cried Frobish. “Don’t you understand the importance of this? Have you no personal curiosity whatever? Are you made of wax that you can live for years in the company of a jar which might very well contain the final answer to the age-old question of demonology? For centuries men have maundered on the subject of witches and devils. Recently it became fashionable to deny their existence entirely and to answer all strange phenomena with ‘scientific facts,’ actually no more than bad excuses for learning. Men even deny telepathy in the face of all evidence. Once whole civilizations were willing to burn their citizens for witchcraft, but now the reference to devils and goblins brings forth only laughter. But down deep in our hearts, we know there is more than a fair possibility that such things exist. And here, man, you have a possible answer! If all historical records are correct, then that jar contains an ifrīt. And if it does, think, man, what the jinn could tell us! According to history, they were versed in all the black arts. Today we know nothing of those things. All records died with their last possessors. Most of that knowledge was from hand to hand, father to son. What of the magic of ancient Egypt? What of the mysteries of the India of yesterday? What race in particular was schooled in their usages? The jinn! And here we have one of the jinn, perhaps, entombed in this very room, waiting to express his gratitude upon being released. Do you think for a moment he would fail to give us anything we wanted in the knowledge of the black arts?”

The fragrant fog from his pipe drifted about Jan’s head and through it his glasses momentarily flashed. Then he sank back. “If I had not already thought this out, I would have no answer for you. There is no doubt but what the ifrīt—if he is there—has died. Hundreds or thousands of years—”

“Toads have lived in stone longer than that!” cried Frobish. “And toads possess none of the secrets for which science is even now groping. A small matter of suspended animation should create no difficulty for such a being as an ifrīt. You quibble. The point is this. You have here a thing for which I would sell my soul to see and you put me off. Since the first days in college when I first understood that there were more things in this Universe than could be answered by a slide rule and a badly conceived physical principle, I have dreamed of such a chance. I tell you, sir, I won’t be balked!”

Jan looked questioningly at Frobish. The fellow had suddenly assumed very terrifying proportions. And it was not that Jan distrusted his physical ability so much as his habitual retreat before the face of bullying which made him swallow now.

“I have given my word,” he said doggedly. “I know as well as you that that jar may well contain a demon from other ages. But for ten years I slaved to forget it and put it out of my mind forever. And I do not intend to do otherwise now. The only friend I ever had gave me that jar. And now, with Greg Palmer dead in the deep of nine south and fifty-one east, I have no recourse but to keep the promise I gave him. He was at pains to make me understand that I would do myself great harm by breaking that seal and so I have a double reason to refuse. I could let nothing happen to you in this …”

“My safety is my own responsibility. If you are afraid …”

Jan, carried on by the dogged persistence of which he was occasionally capable—though nearly always against other things than man—looked at the floor between his feet and said, “I can say with truth that I am not afraid. I am not master of my own house nor of my slightest possessions; I may be a feather in the hands of others. But there is one thing which I cannot do. I do not want to speak about it any further.”

Frobish, finding resistance where he had not thought it possible, backed off, studying the thin, not unhandsome face of his host as though he could find a break in the defenses. But although Jan Palmer wore an expression very close to apology, there was still a set to his jaw which forbade attack. Frobish gave a despairing look at the jar.

“All my life,” he said, “I have searched for such a thing. And now I find it here. Here, under the touch of my hands, ready to be opened with the most indifferent methods! And in that jar there lies the answer to all my speculations. But you balk me. You barricade the road to truth with a promise given to a dead man. You barricade all my endeavors. From here on I shall never be able to think of anything else but that jar.” His voice dropped to a pleading tone. “In all the records of old there are constant references to ifrīts, to marids and ghouls. We have closed our eyes to such things. It is possible that they still exist and it would only be necessary to discover how to find them. And there is the way to discover them, there in that corner. Can’t you see, Mr. Palmer, that I am pleading with you out of the bottom of my heart? Can’t you understand what this means to me? You … you are rich. You have everything you require.…”

“I have nothing. In all things I am a pauper. But in one thing I can hold my own. I cannot and will not break my word. I am sorry. Had you argued so eloquently for this very house you might have had it because this house is a yoke to me. But you have asked for a thing which it is beyond my power to give. I can say nothing more. Please do not come back.”

It was a great deal for Jan Palmer to say. Green and Thompson and Aunt Ethel would have been rocked to their very insteps at such a firm stand had they witnessed it. But Jan Palmer had not been under the thumb of Frobish from the days of his childhood. This concerned nothing but the most private possession a man can have—his honor. And so it was that Frobish ultimately backed out of the door, too agitated even to remember to take the Arabian dhow.

Before Jan closed off the entrance, Frobish had one last glimpse of the copper jar, dull green in the light of the sinking sun. He clamped his mouth shut with a click which sounded like a bear trap’s springing. He jerked his hat down over his brow. Swiftly he walked away, looking not at all like a fellow who has become reconciled to defeat.

Jan had not missed the attitude. He had lived too long in the wrong not to know the reactions of men. He had seen his mother hounded to death by relatives. He had felt the resentment toward wealth, really meant for his father. He had been through a torturous school and had come out far from unscathed. He knew very definitely that he would see Frobish again. Wearily he closed his door and slumped down in a chair to think.

CHAPTER TWO

Jinnī Gratitude

Each evening, when the household was assembled at the dining table, Jan Palmer had the feeling that the entire table’s attention was devoted to seeing whether or not he would choke on his next mouthful. As long as his father had been alive, this had been the one period of the day when he had been certain of himself. His father had occupied the big chair at the head, filling it amply, and treating one and all to a rough jocosity which was very acceptable—until his father had retired to his study for the night. Then it seemed that his rough jests were not at all lightly received. Quite obvious it had been that fawning was a wearying business at best and that those so engaged were apt to revert at the slightest excuse.

Jan didn’t come close to filling the big chair. His slight body could have gone three times between the arms of it. And Aunt Ethel and Thompson, and occasionally, as tonight, Nathaniel Green, found no reason whatever to do any fawning.

Having very early deserted the bosom of his family for the flinty chest of Socrates, Jan knew quite well that if he had had the dispensing of funds comparable to those of his father in his entire control, smiles and not scowls would now be his lot. But the Bering Sea Steamship Corporation was not showing much of a profit. Just why he did not know. He had never peeped into the books but he supposed that these continual strikes had something to do with it. The company paid Thompson and most of Jan’s lot went directly to Aunt Ethel for household expenses. He had, therefore, no spare dollars to spread around.

The deep, dank silence was marred only by the scraping of silver on china. It was as if they all had secrets which they were fearful of giving away to each other or as if they could say nothing but things so awful that they wouldn’t even let Jan hear them. The old house, with its ship models on the mantel and the great timbers across the ceilings and the hurricane lanthorns hung along the walls, wouldn’t have been much louder had it had no occupants at all.

Jan was glad when the gloomy footman put indifferent coffee before them. If he was careful he could gulp it down and get away without a thing being said to him.

But his luck didn’t hold. “Jan,” said Nathaniel heavily, “I trust you will be home this evening.” The question implied that Jan was never to be found at home but always in some dive somewhere, roistering.

“Yes,” said Jan.

“You saw fit to leave today when I needed your signature. When I finally connected with you, I had only time to get the most urgent matters attended to. You are too careless of these serious matters. There are at least twenty letters which only you can write, unfortunately. I am forced to demand that you finish them tonight. If I but had your complete power of attorney you would save me much needless labor. I have so many things to do already that if I were six men with twelve hands I couldn’t get them done in time.”

Strangely enough it came as welcome news to Jan. He almost smiled. “I am sorry I can’t be of more help but I’ll be glad to do the letters tonight.”

Nathaniel grunted as much as to say that Jan better had if he knew what was good for him. And Jan took the grunt as a cue for his departure. Swiftly he made his way to his apartments, fearful that this wouldn’t come out the way he hoped it would.

The first thing he did was strip off his clothes and duck under a shower. He came forth in an agony of haste, losing everything and finding it and losing it again as he swiftly assembled himself. His wardrobe was able to offer very little as Aunt Ethel purchased most of his clothing and did little purchasing. But the dark blue suit was neatly pressed and his cravat was nicely tied and he had no more than finished slicking back his blond hair when a knock sounded.

Hurriedly he flung himself into his chair by the desk and scooped up a book. Then he called, “Come in,” as indifferently as he could.

Alice Hall stepped firmly into the room. As Nathaniel’s stenographer it was her duty, two or three times a week, to call in the evening to let Jan catch up on company correspondence. She was the last of six such stenographers and ever since she had first taken the job four months before, Jan had lain awake nights trying to figure out a way to make certain that she would hold her job. It was not so much that she was beautiful—though she was that—and it wasn’t entirely because she was the only one who did not seem to look down upon him. Jan had tried to turn up the answer in vain. She was a lady, there was no denying it, and she was far better educated than most stenographers, evidently having done postgraduate work. She did not make him feel at ease at all but neither did she make him feel uneasy. When he had first beheld her he had had a hard time breathing.

Her large blue eyes were as impersonal as the turquoise orbs of the idol by the wall. She was interested, it seemed, in nothing but doing her immediate job. Still, there was something about her; something unseen but felt, as the traveler can sense the violence of a slumbering volcano under his feet. Her age was near Jan’s own and she had arrived at that estate without leaving anything unlearned behind her. There was almost something resentful about her, but that too was never displayed.

Now she put down her briefcase and took off her small hat and swagger coat and seated herself at a distance from him, placing her materials on a small table before her. She arranged several letters in order and then stepped over to the blackwood desk and laid them before Jan who, to all signs, was deeply immersed in a treatise on aerodynamics.

Truth told, he was afraid to notice her, not knowing anything to say besides that which had brought her there and not wanting to talk about such matters to her.

She twitched the papers and still he did not look up. Finally she said, “You’re holding that book upside down.”

“What? Oh … oh, yes, of course. These diagrams, you see …”

“Shall we begin on the letters? This one on top is from the Steamship Owners Alliance, asking your attendance at a conference in San Francisco. I have noted the reply on the bottom.”

“Oh, yes. Thank you.” He looked studiously at the letter, his ears very red. “Yes, that is right. I won’t be able to attend.”

“I didn’t think you would,” she said unexpectedly.

“Uh?”

“I said I was sure you wouldn’t. They asked you but Mr. Green will go instead.”

“He wouldn’t want me to go,” said Jan. “He … he knows much more about it than I.”

“You’re right.”

Jan detected, to his intense dismay, something like pity in her voice. Pity or contempt; they were brothers anyway.

“But he really does,” said Jan. “He wouldn’t like it if I said I would go.”

“He’ll be the only nonowner there.”

“But he has full authority.…”

“Does he?” She was barely interested now. Jan thought she looked disappointed about something. “Shall we get on with these letters?”

“Yes, of course.”

For the following two hours he stumbled through the correspondence, taking most of his text from Alice Hall’s suggestions. She wrote busily and efficiently and, at last, closed her notebook and put on her hat and coat.

“Do you have to go?” said Jan, surprising himself. “I mean, couldn’t I send for some tea and things? It’s late.”

“I’ll be up half the night now, transcribing.”

“Oh … will you? But don’t you finish these at the office in the morning?”

“Along with my regular work? A company can buy a lot for fifteen dollars a week these days.”

“Fifteen … but I thought our stenographers got twenty-five.”

“Oh, do you know that much about it?”

“Why … yes.” He was suddenly brightened by an idea. “If you have to work tonight perhaps I had better drive you home. It’s quite a walk up to the car line.…”

“I have my own car outside. It’s a fine car when it runs. Good night.”

He was still searching for a reply when she closed the door behind her. He got up, suddenly furious with himself. He went over to the fireplace and kicked at the logs, making sparks jump frightenedly up the flue. In the next fifteen minutes he thought up fifteen hundred things to say to her, statements which would swerve her away from believing him a weak mouse, holed up in a cluttered room. And that thought stopped him and sent him into a deep chair to morosely consider the truth of his simile. Time and again he had vowed to tell them all. Time and again something had curled up inside of him to forbid the utterance.

Sunk in morbid reverie, he failed to hear Aunt Ethel enter and indignantly turn out the lights without seeing him in the chair. He failed to see that the fire burned lower and lower until just one log smoldered on the grate. He failed to hear the clock strike two bells, and so the night advanced upon him.

With a start he woke without knowing that he had been asleep. He was cold and aching and aware of a wrong somewhere near him. Once again sounded the creepy scratch and Jan stood up, shaking and staring intently into the dark depths of the room. Someone or something was there. He did not want to turn on the light but he knew that he must. He found the lamp beside the chair and pulled its cord. The blinding glare whipped across the room to throw his caller into full relief.

The curtains were blowing inward from the open window and the papers were stirring on the blackwood desk. And in the corner by the copper jar stood Frobish, nervous with haste, a knife peeling back ribbons of lead from the seal. For an instant, so intent was the interloper, he did not become aware of the light. And then he whirled about, facing Jan.

Frobish’s eyes were hot and his face drawn. There was danger in his voice. “I had to do this. I’ve been half crazy for hours thinking about it. I am going to open this copper jar and if you try to stop me …” The knife glittered in his fingers.

It was very clear to Jan that he confronted a being whose entire life was concentrated upon one object and who was now driven to a deed which, had conditions been otherwise, would have horrified no one more than Professor Frobish. But, with his goal at hand, it would take more than the strength of one man to stop him.

“You said you promised,” cried Frobish. “I have nothing to do with that. You are not opening the jar and you were not commissioned to see that it was never opened by anyone. Your cousin was protecting only you and himself. He cared nothing about anyone else. If any harm comes from this, it is not on your head. Stay where you are and be silent.” He again attacked the stopper.

Jan, his surprise leaving him, looked anxiously along the wall. But there were no weapons on this side of the room beyond an old pistol which was not loaded and, indeed, was too rusty to even offer a threat.

A sudden spasm of outrage shook him. That this fellow should presume to break in here and meddle with what was his was swelled with years of resentment against all the countless invasions of his privacy and the confiscations of his possessions.

Shaking and white, Jan advanced across the room.

Frobish whirled around to face him. “Stand back! I warn you this is no ordinary case. I won’t be balked! This research is bigger than either you or me.” His voice was mounting toward hysteria.

Jan did not stop. Watchful of the knife, unable to understand how the professor could go to such lengths as using it, he came within a pace. Frobish backed up against the wall, breathing hard, swinging the weapon up to the level of his shoulder.

“I’ve dreamed for years of making such a discovery. You cannot stop me now!”

“Be quiet or people will hear you,” said Jan, cooled a little by the sight of that knife. “You can leave now and nothing will have happened.”

Frobish was quick to sense the change. He reached out and shoved Jan away from him to whirl and again pry at the stopper. Jan seized hold of his shoulder and spun him about. “You’re insane! This is my house and that jar is mine. You have no right, I tell you.”

Savagely Frobish struck at him and Jan, catching the blow on the point of his chin, dropped to the floor, turned halfway about. Groggily, he shook his head, still unwilling to believe that Frobish could fail to listen to reason, unable to understand that he was dealing with forces and desires greater than he could ever hope to control.

Once more Frobish flung him away and would have followed up, but behind him there sounded a thing like escaping steam. He forgot Jan and faced the jar to instantly stumble back from it. Jan remained frozen to the floor a dozen feet away.

Black smoke was coiling into the dark shadows of the ceiling, mushrooming slowly outward, rolling into itself with ominous speed. Frobish backed against a chair and stopped, hands flung up before his face, while over him, like a shroud, the acrid vapors began to drop down.

Jan coughed from the fumes and blinked the tears which stung his eyes. The stopper was not wholly off the jar and stayed on the edge, teetering until the last of the smoke was past, when it dropped with a dull sound to the floor.

The smoke eddied more swiftly against the beams. It became blacker and blacker, more and more solid, drawing in and in again and finally beginning to pulsate as though it breathed.

Something hard flashed at the top of it and then became two spiked horns, swiftly accompanied by two gleaming eyes the size of meat platters. Two long tusks, polished and sharp, squared the awful cavern of a mouth. Swiftly then the smoke became a body girt with a blazing belt, two arms tipped by clawed fingers, two legs like trees ending in hoofs, split toed and as large across as an elephant’s foot. The thing was covered with shaggy hair except for the face and the tail which lashed back and forth now in agitation.

The thing knelt and flung up its hands and cried, “There is no God but Allah, the All Merciful and Compassionate. Spare me!”

Jan was frozen. The fumes were still heavy about him but now there penetrated a wild animal smell which made his man’s soul lurch within him in memory of days an eon gone.

Frobish, recovered now and seeing that the thing was wholly on the defensive, straightened up.

“There is no God but Allah. And Sulayman is the lord of the earth!”

“Get up,” said Frobish. “We care less than nothing about Allah, and Sulayman has been dead these many centuries. I have loosed you from your prison and in return there are things I desire.”

The ifrīt’s luminous yellow eyes played up and down the puny mortal before him. Slowly an evil twist came upon the giant lips. A laugh rumbled deep in him like summer thunder—a laugh wholly of contempt.

“So, it is as I thought it might be. You are a man and you have loosed me. And now you speak of a reward.” The ifrīt laughed again. “Sulayman, you say, is dead?”

“Naturally. Sulayman was as mortal as I.”

“Yes, yes. As mortal as you. Man who freed me, you behold before you Zongri, king of the ifrīts of the Barbossi Isles. For thousands of years have I been in that jar. And would you like to know what I thought about?”

“Of course,” said Frobish.

“Mortal man, the first five hundred years I vowed that the man who let me free would have all the riches in the world. But no man freed me. The next five hundred years I vowed that the man who let me out would have life everlasting even as I. But no man let me out. I waited then for a long, long time and then, at long last, I fell into a fury at my captivity and I vowed—you are sure you wish to know, mortal man?”

“Yes!”

“Then know that I vowed that the one who let me free would meet with instant death!”

Frobish paled. “You are a fool as I have heard that all ifrīts are fools. But for me you would have stayed there the rest of eternity. Tonight I had to break into that man’s house to loose you. It is he who has held you captive, who would not let you go.”

“A vow is never broken. You have freed me and therefore you shall die!” A thunderous scowl settled upon his face and he edged forward on his knees, unable to stand against the fourteen-foot ceiling.

Frobish backed up hastily.

The ifrīt glanced about him. Near at hand were the Malay krisses and upon the largest he fastened, wrenching it from the wall and bringing the rest of the board down with a clatter. The great executioner’s blade looked like a toothpick in his fist.

Frobish strove to dash out of the room but the ifrīt raked out with his claws and snatched him back, holding him a foot from the floor.

“A vow,” uttered Zongri, “is a vow.” And so saying he released Frobish who again tried to run.

The blade flashed and there was a crunching sound as of a cleaver going through ham. Split from crown to waist, Frobish’s corpse dropped to the floor, staining the carpet for a yard about.

Jan winced as something moist splashed against his hand and swiftly he scuttled back. The movement attracted the ifrīt’s attention and again the claws raked out and clutched. Jan, assailed by fuming breath and sick with the sight of death, shook like a rag in a hurricane.

The ifrīt regarded him solemnly.

“Let me go,” said Jan.

“Why?”

“I did not free you.”

“You kept me captive for years. That one said so.”

“You cannot,” chattered Jan, “you cannot kill a man for letting you free and then kill another for … for not letting you free.”

“Why not?”

“It … it is not logical!”

Zongri regarded him for a long time, shaking him now and then to start him shivering anew. Finally he said, “No, that is so. It is not logical. You did not let me free and I said no vow about you. You are Mohammedan?”

“N-N-No!”

“Hm.” Again Zongri shook him. “You are no friend of Sulayman’s?”

“I … n-n-no!”

“Then,” said the ifrīt, “it would not be right for me to kill you.” He dropped him to the floor and looked around. “But,” he added, “you held me captive for years. He said you did. That cannot go unpunished.”

Jan hugged the moist floor, waiting for doom to blanket him.

“I cannot kill you,” said Zongri. “I made no vow. Instead … instead I shall lay upon you a sentence. Yes, that is it. A sentence. You, mortal one, I sentence,” and laughter shook him for a moment, “to Eternal Wakefulness. And now I am off to Mount Kaf!”

There was a howling sound as of winds. Jan did not dare open his eyes for several seconds but when he did he found that the room was empty.

Unsteadily he got to his feet, stepping gingerly around the dead man and then discovering to his dismay that he himself was now smeared with blood.

The executioner’s knife had been dropped across the body and, with some wild thought of trying to bring the man back to life, Jan laid it aside, shaking the already cooling shoulder.

Realizing that that was a fruitless gesture he again got to his feet. He did not want to be alone for the first time in his life. He wanted lights and people about him. Yes, even Green or Thompson.

He laid his hand upon the door but before he could pull, it crashed into his chest and he found himself staring into a crowd in the hall.

Two prowler car men, guns in hand, were in front. A servant stood behind them and after that he could see the strained faces of Aunt Ethel and Thompson and Green.

A flood of gladness went through him but he was too shocked to speak. Mutely he pointed toward Frobish’s body and tried to tell them that the ifrīt had gone through the window. But other voices swirled about him.

“Nab him, Mike. It’s open and shut,” said the sergeant.

Mike nabbed Jan.

“Deader’n a doornail,” said Mike, looking at the bisected corpse. “Open and shut.” He took out a book and flipped it open. “How long ago did you do it?”

“About five minutes!” said Thompson. “When I first heard the voices in here and sent for you, I didn’t expect anything like this to happen. But I heard the sound of the knife and then silence.”

“Five minutes, eh?” said the sergeant, wetting the end of his pencil and writing. “And what was this all about, you?”

Jan recovered his voice. “You … you think I did this thing?”

“Well?” said Mike. “Didn’tcha?”

“No!” shouted Jan. “You don’t understand. That jar—”

“Fell on him, I suppose.”

“No, no! That jar …”

Intelligence flashed in Aunt Ethel’s needlepoint eyes. She flung herself upon Jan, weeping. “Oh, my poor boy. How could you do such an awful thing?”

Jan, startled, tried to shake her off, urgently protesting to the sergeant all the while. “I told him not to but he broke through the window and pried at the stopper …”

“Who?” said Mike.

“I’ll handle this,” said the sergeant in reproof.

“He means Professor Frobish, his guest,” said Thompson. “The professor came to see him about an Arabian ship model this afternoon.”

“Huh, murdered his guest, did he? Mike, you hold on here while I send for the homicide squad.”

“Don’t!” shouted Jan. “You’ve got it all wrong. Frobish broke in here to let—”

“Save it for the sergeant and the boys,” said Mike, shaking him to quiet him down.

Jan glared at those around him. Thompson was looking at him in deep sorrow. Aunt Ethel was wiping her eyes with the hem of her dressing gown. And all the while Nathaniel Green was pacing up and down the room, squashing fist into palm and muttering, “A murder. A Palmer, a murderer. Oh, how can such things keep happening to me? The publicity—and just when the government was offering a subsidy. I knew it, I knew it. He was always strange and now, see what he’s done. I should have watched him more closely. It’s my fault, all my fault.”

“No, it’s mine,” wept Aunt Ethel. “I’ve tried to be a mother to him and he repays us by killing his guest in our house. Oh, think of the papers!”

It went on and on. It went on for the benefit of the newspapermen who came swarming in on the heels of such a name as Palmer. It went on to the homicide squad. Over and over until Jan was sick and wobbly.

The fingerprint men were swift in their work. The photographers took various views of the corpse.

And then an ambulance backed up beside the Black Maria and while Frobish was basketed into the former, Jan, under heavy guard, was herded into the latter.

And as they drove away, the last thing he heard was Aunt Ethel’s wail to a latecoming newsman that here was gratitude after all that she had done for him too, and wasn’t it awful, awful, awful? Wasn’t it? Wasn’t it? Wasn’t it?

CHAPTER THREE

Eternal Wakefulness

Jan was too stunned by the predicament to protest any further; he went so willingly—or nervelessly—wherever he was shoved that the officers concluded there was no more harm left in him for the moment. Besides, a gang of counterfeiters was occupying the best cells and so a little doubling was in order. Jan found himself thrust into a cubicle, past a pale, snake-eyed fellow, and then the door clanged authoritatively and the guard marched away.

Seeing the cell and the cellmate and believing it was a cell and a cellmate were two entirely different things. Jan sat down on a bunk and looked woodenly straight ahead. He was in that frame of mind where men behold disaster to every side but are so thoroughly drenched with it that they begin to discount it. It was even a somewhat solacing frame of mind. Nothing worse than this could possibly happen. Unlucky Fate had opened the bag and pulled out everything at once and so, by lucid reason, it was impossible for said Unlucky Fate to have any further stock still hidden.

“That’s my bunk,” snarled the cellmate.

Jan obediently moved to the other berth to discover that it was partly unhinged so that a man had to sleep with his head below his feet. Further, the cellmate had robbed it of blankets to benefit his own couch and so had exposed a questionable mattress.

Jan’s deep sigh sucked the smell of disinfectant so deeply into his lungs that he went into a spasm of coughing.

“Lunger?” said the cellmate indifferently.

“Beg pardon?”

“I said have y’got it inna pipes?”

“What?”

“Skiput.”

“Really,” said Jan, “I don’t understand you.”

“Oh, a swell, huh? What’d they baste you wit’?”

“Er …”

“How’s it read? What’s the yarn? What’d they book you for?” said the fellow with great impatience. “Murder? Arson? Bigamy? …”