On Dangerous Ground E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

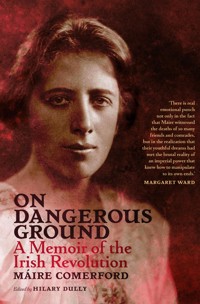

On Dangerous Ground is the revolutionary period memoir of Republican Máire Comerford (1893–1982). This striking memoir, one of the last of its era, includes Comerford's original text, written mainly in the 1940s and '50s, and new material unearthed from her extensive archive that also contains a wealth of photographs and memorabilia from the period. The memoir begins with Comerford's recollection of Sunday strolls to Avondale, former home of Charles Stewart Parnell, who was a neighbour of her father, the mill owner James Comerford. As a young woman, she experiences a 'political awakening' at the hands of a fierce Unionist woman in a secretarial college in London. Máire Comerford (the only Catholic in the class) begins to engage with Irish history books to counterbalance this brush with religious sectarianism. On her return to County Wexford to live with her mother's people – a move necessitated by the family's change of fortune – she re-enters the genteel world of fox hunting and luncheon parties. The memoir paints an intriguing picture of rural life of the time heralding the arrival of the motorcar, social and economic conditions, the rise of the Gaelic League, debates about Home Rule, and the First World War. While the description of her surroundings as a young adult is intriguing and often charming, change is in the air in Ireland and a sharp and wide-ranging political analysis is ever present throughout her writing. Following Comerford's witness account of Dublin during the 1916 Rising, she begins a life of political engagement, joining Cumann na mBan, Sinn Féin and the Gaelic League. In 1919, she moves permanently to Dublin to live with and work for renowned historian and nationalist, Alice Stopford Green. There, she becomes immersed in Republican politics and the War of Independence. Comerford's memoir gives voice to the experience of Republican women during revolutionary times, highlighting the immense contribution of women in the struggle for an Irish Republic. She works all over the country, moving arms, carrying dispatches, finding safe houses, researching atrocities and working assiduously for Ireland. She experiences raids, prison vigils, funerals of her comrades and dangers of all kinds, but nothing cuts as deep as the sense of utter betrayal following the signing of the Treaty in 1922. Comerford takes the anti-Treaty side, is imprisoned a number of times and endures a 27-day hunger strike. Following her release, she leaves Ireland on a tour of east coast American cities to raise funds for the Republican cause at the behest of de Valera. She returns to a harsh, poverty-stricken and lonely existence, eking out a living on a hilltop poultry farm in Wexford. But while her memoir ends in bleak times, her overarching vision suggests an unquenchable optimism – and that the fight will go on. An epilogue by the editor chronicles the years between 1927 and her death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 610

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ON DANGEROUS GROUND

A Memoir of the Irish Revolution

ON DANGEROUS GROUND

A Memoir of the Irish Revolution

MÁIRE COMERFORD

Edited by HILARY DULLY

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

First published 2021 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © 2021 The estate of Máire Comerford

Introduction © Margaret Ward

Epilogue © Hilary Dully

Index by Julitta Clancy

Paperback ISBN 9781843518198

eISBN 9781843518204

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Lilliput Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Printed in Kerry, Ireland, by Walsh Colour Print

Contents

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION: Máire Comerford – an appreciation

On Dangerous Ground

Avondale

Rathdrum

Ballycourcey

From School to Rotten Row

Home Rule

World War

Etchingham

Rising

The Risen People

Ashe

Sisters

Conscription

Women

1918 Election

The First Dáil

Living on the Green

My Half-Mile Radius

Inside Nos 6 and 76

Close Shaves, and Vigils

Raids, Escapades and Escapes

Visits and Visitors

Bodenstown to Leitrim

Trips to Tipp

A Spy and a Mystery Man

Wicklow and Local Bodies

Unwelcome Visitors

1920–21

Arrests and Escapes

White Cross

Housekeepers

Thin Red Line

Truce

Beds

Dresses and Delegations

The Split

Flying the Flag

Making and Breaking Pacts

The ’22 Election

Post-election ’22

Inside the Courts

The Hotel

Driving and Dodging

The Final Chapter

EPILOGUE: What Máire Did Next

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

APPENDIX: Newspaper Articles on Máire Comerford, 1923

INDEX

PLATES

PREFACE

When I first met my husband, Joe Comerford, in the mid-1980s, I also ‘met’ his much-loved aunt, Máire Comerford, although she had died a couple of years previously. Initially, I made Máire’s acquaintance though her library of heavily thumbed and annotated Irish history books and pamphlets, in her collection of Republican memorabilia, in the boxes of her extensive archive – piled high in her former home, St Nessan’s in Sandyford village, Dublin. But most of all I got to know Máire Comerford through the pages of her memoir of the Irish Revolution. When I read her account of that turbulent (and still strongly contested) period of Irish history, I was enthralled by her bravery, idealism and unbreakable commitment to fighting for an independent Irish Republic. I was also struck by the fact that she was, for all intents and purposes, a female combatant on a war footing in the Irish Revolution. In the 1980s, the role played by women during the revolutionary period, apart from figureheads such as Countess Markievicz and Maud Gonne McBride, was largely unknown. Máire’s account not only focused on her story in the fight for independence from Britain, it also introduced a band of extraordinary women and men engaged in the same pursuit – some well-known, but many others virtually lost to history. This great citizen army, mobilized in common cause, is surely one of the most intriguing aspects of the War of Independence; On Dangerous Ground brings us closer to understanding how this worked on a day-to day basis. That their common goal was thwarted, at least in part, makes the tragedy of the Civil War all the more poignant.

My approach to editing the memoir was grounded in a simple methodology, or guiding principle – to preserve the authenticity of Máire’s voice in the telling of her own story. I was determined to avoid any retrospective contextualization of her witness account. Máire believed, as I do, that the construction of history is rarely a neutral exercise; it is constantly evolving and changing through new research and interpretation, often in tune with the forces of present-day political realities and power struggles.

Máire Comerford deposited a version of her memoir with University College Dublin Archive in the 1970s, but this document was far from complete. An exploration of the contents of her archive revealed that there was additional memoir material available, including the concluding chapters of this edited version. I also discovered chapters and notes related to Máire’s childhood and upbringing, and the social and political forces pre-1916, which began to shape and change the temper of the country. These forces, including the fight for Home Rule for Ireland, World War I and the rise of the Volunteers, combined to set in train the gradual politicization of a young woman, living on the fringes of the gentry in County Wexford. Máire was christened Mary by her parents and was known as Mary Comerford to most of her comrades during the revolutionary period, and by her wider family for the duration of her lifetime. This Mary/ Máire identity is central to understanding her political awakening and subsequent life-long Republicanism. As such, throughout the memoir, she is occasionally Mary, but more often Máire.

Máire Comerford spent the latter years of her life writing, rewriting and editing her own narrative. My first job as editor was to gather together all this material and to begin the process of creating a broadly chronological narrative from the various versions of the available memoir chapters. I was always conscious that On Dangerous Ground was written to examine the revolutionary period from a Republican perspective. Máire made no apology for that, for this was exactly what she set out to do. She was clear that her memoir was not a historical account in the formal academic sense. Rather, On Dangerous Ground is a participatory witness account of the period, up to the sad conclusion in the bleak aftermath of the Civil War. It is a history told and examined by a woman who was present, on active service, her boots on the ground and moving all around the country. She had skin in the game, and her life on the line. And therein lies its unique historical value. I saw it as my job to find a framework that would allow her story to also tell the wider story of the period, without losing the resonance that comes from actually having been there, totally invested in the Cause; then subjected to a soul-crushing political and military defeat at the hands of former comrades.

Máire continued to write well into her old age with the intention that this memoir would be published in her lifetime – that On Dangerous Ground would find a place in the rich tapestry of the history of this fascinating time. Sadly, this was not to be. As editor of her memoir, I can only hope that almost forty years after her death, I have served her intentions well.

Hilary Dully

INTRODUCTION

Máire Comerford – an appreciation

AS A YOUNG, eager graduate student, desperate to find out more about the activities of Ireland’s revolutionary women, it was suggested to me that I should arrange to meet Máire Comerford. In my shy letter of introduction, I ended by saying that I would be in her debt forever. How true were those words. How much we are all in her debt becomes apparent on reading this wonderful account of her life and her participation in the Irish revolution. Her clear eye, extraordinary recall and attention to detail, coupled with an unerring ability to be at the heart of so much of the action, provides the reader with a witness account that rivals any of those produced by her male contemporaries. Her political acuity, evident in her growing understanding of the forces that were to create what she always termed the ‘counter-revolution’, generates an additional layer of complexity. There is real emotional punch not only in the fact that Máire witnessed the deaths of so many friends and comrades, but in the realization that their youthful dreams had met the brutal reality of an imperial power that knew how to manipulate to its own ends.

The organization she joined, Cumann na mBan, was the women’s auxiliary to the male Volunteer movement. It began as a support organization, raising funds, learning first aid and making up field kits, but by the time of the War of Independence it was a highly militarized body, working closely with the men, moving armaments, scouting for operations, passing messages and finding shelter for those on the run. In the Civil War period, the women’s role was even more vital, and almost 500 were imprisoned by their former comrades. The majority of female activists stayed in their local area, supporting the guerrilla war from their home base. After the 1920 local government elections a small proportion of women also gained experience of local politics as they worked to establish the administration of Dáil Éireann. What makes Máire Comerford’s autobiographical account of those days so valuable is the fact that she did not remain with her Wexford branch of Cumann na mBan but became an activist in many different spheres. As she said to me in 1975, ‘the work I got into independently [of Cumann na mBan] was much more interesting – it brought me out around the country’. Through the distinguished historian Alice Stopford Green she became acquainted with many influential figures. As worker for Sinn Féin, the Dáil and the White Cross, travelling throughout the country, her lively intelligence and powers of description make her an invaluable witness.

Even as a young child Máire’s eye for a telling detail is remarkable. The Comerford family home in Rathdrum was close to Avondale, the Parnell estate. Her father James had been friendly with Parnell and after his death her redoubtable mother Eva would visit the ageing Delia, then living alone. When the contents of the house were auctioned, the ruined state of the Parnell billiard table made a deep impression; a small vignette, but an effective illustration of the sorry history of the Parnell split and the gradual demise of Irish parliamentarianism.

Although Catholic, the Comerfords were part of the gentry of Wexford. Eva was the daughter of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Esmonde and a tennis champion, golfer and expert rider to hounds. However, family finances declined as James Comerford resisted market demands to bleach his flour. After his death his widow brought her family back home to Wexford. As Máire’s journey into political activism began, so too did her clashes with the wider family, who eventually sent her to a fashionable convent school in England. There are many echoes of Kate O’Brien. When she is taken to a debate on home rule by her cousin, Sir Thomas Esmonde MP, sitting alone in the ‘ladies cage’ as Anna Parnell did before her, her unease with British rule over Ireland intensifies. After attending a performance of Cathleen Ni Houlihan in the Royal Court Theatre, Sara Allgood in the leading role, Máire knew her course in life was settled: ‘I wanted to win back the Four Green Fields.’ Her secretarial school in London was run by a friend of her mother’s, a ‘furious Unionist of Anglo-Irish landlord stock’, who gave her pupils the Ulster Covenant and speeches of Carson as exercises for shorthand and typing. Máire, picked on as the only Catholic, soon made up her mind: ‘I would be nobody’s secretary except on my own terms – in, and for, Ireland.’

She began by helping her cousin Ellice Pilkington, honorary secretary to the United Irishwomen, soon to rename itself the Irish Countrywomen’s Association. It was Máire’s first experience of a conscious policy of keeping women out of the political sphere. Her emerging feminism began to be articulated as she argued good decisions could only come from ‘an equal partnership between the sexes’. She struggled to learn Irish but loved the Gaelic League, which gave them ‘a classless society of idealists. It was not to last long, but it was lovely to be in it.’

Her ability to find herself in the heart of events begins in Easter 1916 when she stays with an invalid cousin in Rathgar. Returning from Blackrock on the Easter Monday she discovers she was now in the heart of the rebellion and her excitement is conveyed as she walks along the tramlines, crowds talking and wild rumours spreading. A sentry at the St Stephen’s Green barricade would have brought her into Countess Markievicz but she returns to Rathgar, promising to come to the Green the next day. However, next morning she sees blood in the doorways around Harcourt Street but no sentry. It would be her only missed opportunity.

Her sympathies lay with Liberty Hall, which she had visited when she first came up to Dublin and went back to when her family arranged a shopping trip to Dublin. Máire (having secreted a few stone of Wexford potatoes as a present) met Markievicz and Marie Perolz (who offered to supply her with a .22 revolver). She becomes firm friends with the group of Wexford activists, Seán Etchingham, Father Sweetman and Aileen K’Eogh, matron at Father Sweetman’s school. When Aileen is arrested Eva Comerford cycles the twenty miles to help at the school. Dulcibella Barton, sister of Robert Barton, part of the local gentry, is also strongly Republican. Máire ends up escorting many of those on the run to the Barton home, both in the Tan War and in the Civil War.

Appointed a Cumann na mBan organizer for North Wexford, helping with anti-war campaigns – ‘with that soil under one’s feet, and a job to be done, it was heaven to be young’ – she finally gained her independence when Alice Stopford Green, a paying guest at her mother’s home (together with Jack Yeats and others) invited her to live in her St Stephen’s Green home and work as her secretary and researcher. Here she meets the famous and the influential. In late evening she also has ‘three or four hours of glorious freedom’ ‘to see what one person could do for the Irish Republic’. There are fascinating snippets of social history: the small girls Mrs Green calls ‘Dublin’s little mothers’ escorting toddlers and babies from the slums to the sandpit at the Green, and small boys pretending to shoot each other, ‘Alan Bell – your time has come.’ The apple and flower sellers with their ‘capacious aprons’ ever ready to help a Volunteer with a smoking revolver or undischarged bomb, ‘Drop it here, son’. The half-mile radius of the Stopford Green house was a hive of Republican activity, with the Dáil, Sinn Féin and Cumann na mBan all having HQs nearby.

In October 1920 Stopford Green released Máire to work for the Dáil Publicity Department, reporting on the Tan reign of terror. In early 1921 she was working for the White Cross, reporting on the impact of the destruction of homes and factories and liaising with clergy as relief was paid through parish committees. She meets many of those working to maintain administrative structures, despite the dangers. Some were women – like Maria Curran, chair of Arklow Urban Council, whose services were never properly recognized. Throughout, Máire is alert to the contribution of women. A chapter, ‘Women’, pays tribute to the contribution of feminists like Hanna Sheehy Skeffington while also criticizing Cumann na mBan for letting down women at the end of the war: ‘It never occurred to me to doubt that the Republican government, when we put it in power, would do justice to both sexes equally and, of course, to all of the people.’ Another chapter, ‘Housekeepers’, includes Mrs Woods, ‘when it came to hiding a hacksaw in a cake, Maa Woods was an artist’; the invalid Molly Childers, lying on her sofa, whom she believed had more backroom influence ‘than any other woman in Irish history’ and recognition of the homes where women took great risks in hiding armaments and providing safety to countless men on the run: ‘It took a woman to hold her own floor and hope to be left behind on it after the raiders were finished.’

Máire gradually came to believe that Stopford Green and some of her close associates were pressing for a British compromise to bring an end to war. In Máire’s eyes, victory could contain ‘no compromise, blurred allegiance or any toleration of British rule’. Her worry was that the inexperience of the Irish leaders might lead them to accept joining the emerging Commonwealth. It was Máire and Liam Mellows who rushed to de Valera to tell him of rumours that a compromise solution without a republic had been advanced, and it was Máire, back in the Stopford Green house, who typed up the terms of the truce, given to her by Diarmuid O’hÉigeartuigh. Her misgivings grew. Young officers were now seen around Dublin in new uniforms ‘plus the latest thing in green leather coats and fast cars’. By the time of the Treaty shops were selling ‘Volunteer equipment’ so ‘the stage Irishman got a new uniform’. She now left the employment of Stopford Green and transferred to the Dáil lecture committee. Her friend Lily O’Brennan was over in Hans Place with the Irish delegation and rumours of too much alcohol circulating began to spread.

Unlike many, Máire devotes attention to the Northern counties and their abandonment. She was critical of the fact that the Dáil was not included in any discussion on partition or consulted on the content of the meeting between de Valera and Joe Devlin prior to the 1921 elections. She was an election organizer in Maghera, ‘filled with both fear and fervour’, and always believed that if those who had been elected to Northern constituencies had given up their Southern seats and insisted on representing Northern constituents in the Dáil, they could have posed a real challenge to the partition settlement.

Back to Wexford as an anti-Treaty election organizer with an inadequate £5 a week, the ever-resourceful Máire organized and led a raid on thirty post offices, netting £80 in stamps and a calling to Dublin, to be ‘ticked off very severely’ by Seán T. O’Kelly. Still not thirty and therefore ineligible for the vote, she was determined to have her say in the election. Someone found the name of a dead woman and let her cast her ballot.

As move and countermove towards a civil war begin, Eva Comerford comes to Charlotte Despard and Maud Gonne MacBride, helping the Belfast refugees sheltering in Roebuck House. Bored with gardening, Máire leaves Roebuck and volunteers at the Four Courts, remaining there throughout the bombardment. Refusing to surrender she slips away and offers her services to those in the Hamman Hotel. Markievicz is there on the roof, in her ‘usual state of being alert with a rifle poised’. The descriptions of the Dublin resistance are memorable. There are vignettes of all the key figures and unforgettable images, like the pyramid of bath towels in the middle of the hotel foyer shielding Father Albert hearing confession, and the unending chain of men carrying filled sandbags to the roof. At the end she is a member of the Cumann na mBan guard of honour at Cathal Brugha’s funeral, watching flies moving on his face. She joins the retreating forces, driving a Republican car and ‘more in the IRA than out of it’ and is eventually arrested, informed on by her former colleague Min Ryan, now married to Richard Mulcahy. Shot and wounded while in Mountjoy she is later transferred to the North Dublin Union, from where she escapes.

Another election, this time organizing in County Cork before being sent by de Valera on a propaganda mission to the USA. Smuggled over on a false passport as ‘Edith Lewis’ she is desperately homesick but home, when she returns, is no longer a place of comradeship and excited hopes. Now there are years of poverty and isolation as she tries to scrape a living as a poultry farmer in Wexford, with land loaned to her by her friend Father Sweetman. She remains a Cumann na mBan activist, suffering further imprisonment, but by the time of her expulsion from Sinn Féin in 1927 concludes that the Republican opposition is going nowhere. Ultimately, her hopes were with the younger generation that she befriended so generously.

I am delighted that, at long last, the manuscript Máire Comerford devoted the last years of her life to writing is now in print. To her and to all the women of that revolutionary generation, my deepest appreciation.

Margaret Ward

ONDANGEROUS GROUND

Avondale

WHEN I WAS a child it was a Sunday ritual in Rathdrum for people taking an after-dinner walk to stroll the mile or two to Avondale – the ancestral home of Charles Stewart Parnell. While travelling there and back before benediction, I came to know every stone of that road. I was born in 1893 and first travelled it by perambulator, but as I grew older, and began to eavesdrop on adult conversation, I do not recall any talk that the grown-up people must have had among themselves, remembering Parnell’s glory, and his disgrace.1 When later I was told about the fateful day of Parnell’s final homecoming, from Brighton to Glasnevin, I imagined the ritual Sunday walk might be classed as a kind of permanent continuation of the funeral march for Parnell, who did great things for Ireland.

When we walked the avenue and reached the big house itself – long empty of human life – we took turns looking through a window into the square hall, where bundles of papers were piled along the walls. This was Avondale as it was before the auction; I recall the billiard table in the hall, the green baize risen up to form mountains and valleys, where moulds grew in more vivid colour, in the damp closeness of the house. At home I had been taught that our billiard table was sacred and that no child might put a finger on the green part of it; that Parnell’s table should be in that condition made a deep impression on me. The house must have been closed for five or six years at the time of which I write.

My father, James Comerford, and Parnell were born about the same time – in the Famine years. One was Catholic and the other Protestant, but they both rode and drove the best horses to be had and liked to play cricket. I do not remember that my father ever mentioned Parnell until the time of the auction. Then, I heard the discussion between him and my mother about the book that must be bought. This book, The Rise and Fall of the Irish Nation by Jonah Barrington, really belonged to my father. Parnell had borrowed it and now we wanted it back to have in memory of him. As it turned out we did not retrieve our book because the library in its entirety was bought up beforehand. What we did manage to purchase was a Sheraton tea caddy on legs; I remember that coming home, and the polishing it got.

Long afterwards my mother told me the story. When my father and Parnell were both young men, and friendly neighbours, Parnell sometimes dropped in on my father to find him busy in his flourmill. Parnell was just home from Cambridge University and preparing to take up the reins of his ancestral estate. His mother, Delia Stewart, daughter of the famous American naval admiral, lived with him at Avondale. Charles was then unmarried.

Our mill in Rathdrum may well have been the most up to date of its time. The Comerford brothers and business partners, my father and Uncle Bill, had incorporated their own inventions in its works. The patents and pricelists for machines, which they built and sold both in England and Europe, still exist. My father was known for demonstrating the efficiency of the grindstones, balanced according to his particular invention; he liked to insert a visiting card, his own or his guests, to show how he could shear away the printed name without breaking the card itself. After some such occasion as this, Parnell lamented that he had nothing to do and they exchanged books; after- wards he told my father that The Rise and Fall of the Irish Nation had turned his thoughts to politics. In it Parnell read of the part played by his ancestor, Sir John Parnell, in the rise of the Volunteers2 of 1782, and his opposition to the Act of Union3 enacted in 1801.

Old Mrs Parnell continued to live in Avondale when Charles and his sister Fanny were both dead, and her other children absent. When she was newly married, my mother made regular visits to Mrs Parnell and afterwards told of her apprehension when she found the old lady, seated in the cane chair, which she continually drew nearer to the hearth, as she read a book by the light of a candle held in her hand. Mother recalled seeing some leaves of the book scorched where they had caught fire, and the old lady, patting it with her hand, had quenched the flame. She returned from Avondale frightened at the danger the elderly woman was in, but Mrs Parnell could not be persuaded to protect herself. As was inevitable, that brave and generous American lady died in a fire.

In her day in Dublin, Delia Stewart Parnell held an open house for the Fenians.4 When she toured the United States in the Irish cause Delia was acclaimed as the daughter of an American hero and in this role her popularity widened the Irish influence beyond the normal scope of the immigrants and their descendants. Mother was the only witness I ever knew to Delia Parnell’s old age, which was sad, lonely, and I think by the standards of her class at the time, poverty-stricken.

Our Comerford branch came to Rathdrum from Ballinakill in County Offaly. Kilkenny, like Galway, had its ‘Tribes’; but the Catholic Tribes like the Walshes and the Comerfords were evicted from the city of Kilkenny and ordered to live at Ballinakill. All this happened a very long time before our story began in Rathdrum. In a quiet way the Comerfords belonged to a class of Irish person who seemed relatively unaffected by the Penal Laws against Catholics; people engaged in primary industries – brewers, millers, wool merchants – who thrived relative to the many Irish people who depended for their livelihood on the land and nothing else. We were well enough off to enjoy life to the full and to be socially accepted as much, or almost as much, as other well-off Catholics of independent means at the beginning of the twentieth century. My mother, Eva Esmonde, was judged to have come down in the world when she married my father. On her equally Catholic but prouder side, there was a pedigree – supplied by request from the senior Esmonde family members to the editors of Debrett, and likewise to Burke.5 I never knew anyone to buy either volume, but I held onto some proofs, which came every year until we were dropped.

But we, the younger branch, went even further to the right and were downright ‘Castle Catholic’.6 This happened when my grandfather won a Victoria Cross – for throwing himself on a shell in the Crimea and thereby quenching it. He came home from the Crimea and Burmese War and landed at Southampton. But the welcome there was too much for him and our family folklore tells of Queen Victoria giving him a day or two to sober up, before she could pin the Victoria Cross on his breast at a separate ceremony; this was followed in Ireland by a hero’s wedding to my grandmother, who was a ‘Castle’ beauty of several seasons. When my grandparents married, my grandfather was given the job of Deputy Inspector in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). Thomas Esmonde VC was a small man with a black beard, who enjoyed riding in races. He was in command of the RIC at the time of the Orange?7 riots in Belfast in 1867. His descriptions of action in the city included charging around on a horse, trying to provide protection for Catholic Mill girls, who were cut off by the mob from collecting their wages. In the end, when quiet was restored, Grandfather Esmonde had to send to Dublin for an implement to un-lead the police rifles. The usual way was to fire them off but he dared not do that, lest the sound of a thousand shots might cause the trouble to surge up again.

My grandfather had an accident to his eye in the hunting field and the family moved to Bruges in Belgium, where he died. They were living there at the time of the Franco-Prussian War. Mother’s account of the enforcement of conscription, and their friendship with the people in the country place where they lived, was often repeated when we were children. Only a proportion of the young men had to go to war, and the fate of all was decided publicly by lot. The ceremony produced a gathering of the families of the youths. For them, the drawing of a conscript’s lot was equivalent to a sentence of death; there was little or no hope that the unfortunate chosen would be seen alive in their native place ever again. Mother cannot have been more than ten years old when she witnessed these scenes, which undoubtedly made an enormous impact on her, and, in course of time, on me.

In contrast to this, it seemed to me that she was rather more reticent about the political events and the circumstances of their lives after they returned to Ireland. Granny was still beautiful and was welcomed back into the Castle set. When she took up residence in Kildare Street, lodging for the season of balls and receptions, my debutante aunts found their way somewhat obstructed at times by granny’s elderly suitors plopping on their knees to propose marriage.

Of my three aunts, two, Zephie and Millie, were too loyal to their Church to marry the young Protestant officers with whom they fell in love, and from whom they parted in a firm spirit of resignation. My mother, Eva, never went to the Castle but this was not because she didn’t like dancing. She often described how she and her sisters and brother hired a strange one-horse covered vehicle, travelling up a dozen rough and muddy miles each way to attend dances in what were certainly landlord-class houses. Mother told me how on one night of heavy frost, on their way to a ball at Mount Nebo near Gorey, they had to get out in all their finery and push the contraption up Hollyfort Hill. This was probably in the late 1880s – a time when blinds had to be drawn in landlords’ and agents’ houses before the oil lamp could be lit; this was in case some angry Land Leaguer8 might shoot at an enemy of the people, unwary enough to show himself between a lighted lamp and an uncovered window.

In her sisters’ view, when Mother married my father, she married the baker and therefore beneath her. I, it turned out, was only to be expected from such a union. But there was a very real affection between us and the aunts and it was proved on both sides. Later, in moments of pain and anguish to them, because of my politics or associations, I never heard them say anything stronger than, ‘Of course you would not understand but this is what we think.’

If people concerned themselves with all their ancestors, instead of those they like best, it would be understood that if heredity does indeed influence actions it must in a very chancy and unpredictable way. For as well as being the daughter of an Empire soldier – perhaps to be classed a mercenary like more Irishmen of his kind – Mother was also a direct descendant of Doctor Esmonde, who sat in the Back Lane Parliament of 1792 in Tailors’ Hall with Theobald Wolfe Tone,9 and was afterwards hanged where O’Connell Bridge now stands.

1 Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–1891) began his political career as a land reform advocate and was first elected to the British parliament for the Irish Home Rule League (later the Irish Parliamentary Party) in 1875. Parnell employed obstructionist methods in parliament in order to bring Irish issues centre stage. His ‘disgrace’ was heralded by the divorce proceedings brought by fellow Irish politician William O’Shea, citing the adultery of his wife, Katherine, with Parnell. This led to a public scandal and a split in the Irish Parliamentary Party.

2 The first Volunteers were enrolled in Ireland in 1778, following the outbreak of war between Britain and France and amidst rumours of the imminent invasion of Belfast by the French. The Volunteer movement grew to a membership of 80,000 men by 1782. The Volunteers of this period espoused loyalty to the Britain Crown, alongside a resolve to uphold a distinct Irish strategy.

3 The Act of Union of 1801 rested on legislation, introduced in 1800, which effectively dissolved the Irish parliament that had existed since the thirteenth century, bringing Ireland into a legislative union with Great Britain. There was resistance to the proposed legislation in the Irish parliament but, through bribery or patronage, the government of William Pitt secured a majority in both houses of parliament and the Union came into effect in 1801.

4 The Fenians were a nineteenth-century resistance organization, based in Ireland, the USA and Britain, who engaged in revolutionary activities, including a failed uprising against the British in 1867.

5 Debrett’s Peerage and Baronetage is a publication listing the titled aristocracy or British peerage, first published in London in 1802 by John Debrett as Peerage of England, Scotland, and Ireland. A similar publication – Burke’s Peerage, first published in 1826, was a guide to the Peerage of Great Britain and Ireland.

6 The derogatory term ‘Castle Catholic’ was applied to well-off Irish Catholics integrated into the pro-British establishment and administration in Dublin Castle.

7 The Orange Order is an Irish Protestant, political and sectarian society, named for the Protestant William of Orange (King William III of Great Britain), who defeated the Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The society was formed in 1795, arising out of local sectarian conflict in County Armagh, but over time increased its influence, becoming an important infrastructural element of political Unionism.

8 Land Leaguers were members or supporters of the Irish National Land League, founded in Castlebar, Mayo, in 1879, when Charles Stewart Parnell was elected president. The League worked to abolish landlordism in Ireland and to enable tenant farmers to own the land they worked.

9 In 1792 Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763–1798) was appointed assistant secretary of the Catholic Committee, set up to improve the rights of Irish Catholics in Ireland. In December 1792 members of the committee met in Tailors’ Hall in Back Lane, Dublin, subsequently known as the ‘Back Lane Parliament’. Wolfe Tone was one of the founding members of the United Irishmen (1791) and a leader of the rebellion against the British in 1798. He was captured and sentenced to death by hanging in November 1798. Days after his sentencing Wolfe Tone died in prison from a self-inflicted wound to his throat.

Rathdrum

I DID NOT KNOW of it for many a year afterwards but Ardavon, the house where I was born and spent my childhood, was built a little bigger in all its dimensions than the limit that was permitted on the Meath Estates for Lord Meath’s Catholic tenants. Ardavon was a beautifully placed house with a view of the Vale of Clara, overlooking the mill, which was my father’s pride and joy.

The Lord Meath of my childhood was a venerable gentleman with a flowing white beard. He was then Lord Lieutenant of the county and the times had changed. It was the policy to appoint Catholic magistrates at that time. This was ‘an honour’, which my father had declined. Voices in the hall of Ardavon drew me from my bed one evening, probably around 1900. I watched through the bannisters, from the upstairs landing, a heated argument between the two, when my father refused to agree to whatever was under discussion. I found out later that Lord Meath had called to announce that he had put my father’s name down as a magistrate, whether he liked it or not! I heard my father resist and repeatedly say no until the old gentleman gave up and went on his way.

The old mill was burned down in 1885, some years before my parents met and married; the grindstones were never to be set and balanced again. It was quickly rebuilt and equipped with the latest roller machinery, which was then making a revolution not only in the flour-milling industry but also, as happened eventually, in the diet of the people, as the craze developed for whiter and whiter flour. The new mill had only been up and running for three days when some hundred members attending the British and Irish Millers Convention, which was held in Dublin that year, visited it in 1886. The press account describes the mill and its machines, with mahogany furnishings, silk sifting, and the new dust-catcher – the last of the firm’s inventions, which was sold all over the world. The quality of the flour was praised and mention was made of semolina, the new-fashioned product made from the germ of the wheat. The germ was now being taken from the flour, and therefore from the bread, in order to have flour that would last longer and make a whiter loaf.

I suppose things went well for the next ten or so years. My parents married in 1892. My father’s wild oats were well sown. He handed the hunting hounds over to Lord Wicklow,1 and gave up steeplechase riding, as an amateur jockey under the alias of ‘Mr Thorne’. My parents met hunting and married when my father was forty-eight and my mother thirty-one. In those days the railway had important social significance and the hunting people engaged special carriages and horseboxes for their meets; then, in the evening, they held parties while waiting on railway sidings to be picked up by the returning train. My mother was Irish women’s tennis champion for two years; she was also a hard and valiant rider in the hunting field, and a very good golfer. When their four children were old enough our parents gave us donkeys and ponies. I rode in a box saddle before I could walk, and don’t remember having to walk anywhere until I was well into my teens.

I was the eldest and luckiest of the four children, and because of being older than my sister and two brothers, our wonderful childhood, up to the time we had to meet the real world, was best for me. Most children now seem to be taught to be afraid; we learned to fear nothing, and to perfect ourselves in dangerous country skills – with horses, with fire and water, and judgment of tides and river currents, with the behavior of cattle, rams and ganders, strange dogs, and boats; we learned to judge speed, if only of horse or bicycle. From the time our legs were firmly under us, our parents encouraged us in independence and widening adventures – climbing, rambling across country, exploring without let or hindrance.

There were, however, certain rules of expected conduct. If bucked by your pony, make no fuss, get up again, and again, no matter how often he bucks you, no matter how hurt; afterwards water and feed the pony before you eat yourself; never cheat at games; don’t whinge. When there was an occasion for tears, I held them until I got to a warm, dark stable, where I could be nuzzled by a soft nose, and caressed by the warm breath of an animal; my tears may have startled the half curious, but wholly uncritical beasts.

My parents were musical and hoped for musical talent in the family. In this, I was the conspicuous disappointment. Coaxing, coercion, and even bribery to induce me to stay at the piano, all failed; instead, I developed tactics of passive resistance, which were to serve me well in other circumstances of life in later years. My mother and father never, in bad times or good, suggested or required from any of their children any compromise to expediency; that was the world into which we were born, and in which I participated with zest and vigour, until the times changed. I dimly recollect a point in time when our parents recognized that their girl children, as well as their boys, would have to earn a living. This registered for the first time on a Saturday night when I was called to the table to help count the takings, putting the money into little heaps. It was a task not destined to tax any of us much in the years ahead.

There was no love lost between my mother and my father’s relations. Mother would have liked to have a family home of their own rather than living in the firm’s house, with business intruding all the time. When Uncle Bill died, his nephew became the new partner in the firm and began to push relentlessly for the newer milling methods. I remember great arguments, elevated feeling in Ardavon, when my father refused to use artificial methods to whiten the flour. In the mill, men in white coats followed my father with samples of other people’s flour, which he brushed aside in high temper. My father said that the business had become dishonest and dishonourable, and that he would not tamper with people’s food. He would have nothing to do with bleached bread and resisted the new bleaching process to the point of ruin. Instead of being at the top of his profession, my father now had his back to the wall. Every Saturday when the travelling salesmen came in with money to be counted on the dining-room table, and with next week’s orders, it was the same story – business was falling off. The mills we were in competition with were offering the whitest of white flour. The law is strict now regarding the use of ‘conditioners’ in the manufacture of flour but there was no such protection for the public when the battle was fought out in our home at the turn of the century.

Ardavon, so close to the mill, was a busy place and visitors came and went. ‘Here comes the snipe,’ my mother would say when we heard the clatter of horse’s hooves trotting into the yard. This was her description of the Barton sisters, Daisy and Dulcibella from Annamoe, who often came in the hunting season, like the snipe to lowlands in wintertime. We enjoyed their cheery company while the horses rested, before they clattered off again. Dulcibella was destined to be the staunch little figure who surmounted many contingencies when she took charge for her brother Robert Barton at Glendalough House, Annamoe, when he was a Minister in the Government of the First Dáil; or away in prison in the stormy years that were still ahead of us then. Dulcibella was a light sleeper and very keen of hearing. During the War of Independence, and afterwards the Civil War, many a man on the run rested safely with her, relying on the fact that she heard the footsteps of raiders from the moment they touched the well-raked gravel paths approaching the hall and side doors of Glendalough House, which came to be known far and wide as ‘glan’ – a safe house.

Another visitor to Ardavon, who was to make a big impression on me, was Father Sweetman,2 or The Very Rev. Dom J.F. Sweetman OSB – a great personality of his generation. A massive figure of a man, he was wearing white flannels when he walked up the little path from the station one summer day in 1905 or 1906. His blackthorn stick was easily the same thickness as my arm. He was looking for boys for his new school in Wexford and wanted my brothers, Tom and Sandy. Both went to his school near Enniscorthy; later the school, Mount St Benedict, moved to Mount Nebo, near Gorey. On that first occasion of our meeting, I distinctly remember standing jealously aside, furious that he paid no attention to me. He was, however, destined to be part of my story again and again.

Father Sweetman gloried in the fact that he was born on the slopes of Gibbet Hill at Clohamon in County Wexford. From the time he went to school at Downside in England he was determined to be a Benedictine monk, and to bring the order back to Ireland, from where it had been banished long before. It was to get money for that purpose that he volunteered to be a chaplain with the British army in Africa during the Boer War. The army pay supplemented his own family money that went into establishing his school. Other things that he brought back from Africa were good stories, great sympathy for the Boers, and a taste for their tobacco. To hundreds of people, he was simply known as ‘the Reverend Man’.

When I first met Father Sweetman in the early years of the twentieth century, rural Ireland was undergoing great change. Tenants were buying land under the land acts, and men could acquire ownership of land as of right. In all Irish history there had probably not been so many who would become, as it seemed, their own masters in their own fields; men whose rent would never again be increased if they made improvements; men who believed they had the chance to shape their lives and little knew of the odds against them. There was not a man at the fair at Rathdrum, or any other fair in Ireland, who experienced the delight of turning his first sod on his own land – or a woman who lit the oil lamp in her own home, knowing she could paint the door and pay for it out of her egg money – who could have conceived that great change was so close at hand.

Those were the days when people were only beginning to know the countryside outside the small circle where it was pleasant to drive a horse out and back in a day, from and to their homes; apart from that there was the train with the possibility it opened of travelling by sidecar in a similar circle from any of the stations where these cars lined up for hire. We were into the 1920s before taxis would challenge the sidecars.

I saw a motor car for the first time on a Sunday, when the people were walking to Avondale: the second time we were riding along and the horses were sent plunging and rearing. Not long afterwards Lord Wicklow appeared at the hunt meets in an enormous, pale yellow car, chauffeur-driven. I remember his anger one day when he learned that his English chauffeur had driven slowly behind our fleeing ponies, carrying us the whole way home from a meet at Churchmount, and caused us to miss the hunt. Until the motor car came, horses never encountered anything on the roads that could go faster than they could. Our well-fed hunters and trap horses could not bear to be passed, perspiring all over, even when they had ceased to be much afraid when a car overtook. Motorcars took the pride out of the harness horse.

I doubt that bicycles were common much before the time me and my elder brother got them at the age of about ten and twelve. I remember my mother and Aunt Millie learning to cycle at the same time. My bicycle opened Ireland to me. By the time I was twenty-five I had explored the coasts, riding every mile – Wexford, Waterford, Cork, Kerry; and Arklow, Wicklow, Dublin, Drogheda, Dundalk, Belfast, the Giant’s Causeway, Derry and Donegal. I cycled to Kilkenny, and stood on the Hill of Uisneach3 in Westmeath. At first it would be an absence from home for one or two nights. I packed food and carried small money, all that could be saved and enough to buy bed-and-breakfast once or twice. After that the holiday was by muscle power and cost little.

Travelling out from home, I struck across country, not by the biggest roads, which were liable to be very dusty in summer. Tar has taken the buoyancy out of the roads now, and widening has made them trap the winds, so that bicycling is more difficult. The narrow, winding roads of yore were fresh and beautiful, with ass cars meandering and people relaxed, shouting their greetings to one another as carts and traps met and passed, and no one in fear of imminent death.

Our bicycles were the fastest things, at least on down hills, where we let them rip, dodging potholes. History has happened on many of those roads I travelled since I first explored them. Now there are more stopping places, to read a name, say a prayer or learn a story at locations that have been added to the historical places of Ireland.

1 Lord Wicklow, Ralph Francis Howard (1877–1946), was the 7th Earl of Wicklow, an Anglo-Irish peer with an estate at Shelton Abbey, near Arklow, County Wicklow.

2 Dom Francis Sweetman (1872–1953) was a Benedictine monk, Irish patriot and founder of Mount St Benedict, a school for boys in Gorey, County Wexford.

3 The Hill of Uisneach in County Westmeath is the mythological centre of Ireland and an ancient ceremonial site. Spanning five millennia, Uisneach is considered to be one of the most sacred sites in Ireland.

Ballycourcey

MY FATHER had an accident while hunting; the muscle of his leg was severed when a horse jumped on it. As well as being angry about the flour situation, he was now crippled. I remember his hands, always very clean, his two sticks, his white overalls, his care and courtesy if he peeled an orange and handed it to me without his hands ever having touched the part I was to eat – so different was his from other people’s way with us. I was thirteen when my father died after a long illness. He had only succeeded in delaying ‘progress’ for one small firm for a few years but his fight was an honourable one and a cause of pride, which we never regretted, although it left us poor.

After his death there was a big arbitration about the business and when this was complete my mother’s capital was about the same as a few years income in the prosperous years. She had four of us to rear and educate and decided to leave Rathdrum and return to her own people. I can only remember the very few friendships that survived my father’s death, our change of fortune and place of residence. Among these worthy exceptions were the Barton sisters of Annamoe, who mother loved dearly.

Mother brought us back to Wexford, her native county. My mother’s brother, Uncle Tommy Esmonde, had established his mother and sisters in a pleasant Georgian farmhouse and a hundred-acre farm at Ballycourcey, Enniscorthy. This became the family headquarters until, a couple of years later, Mother rented Slaney Lodge, less than two miles away. Following his education by the Benedictines at Downside Abbey, Uncle Tommy went into the service of the Irish Land Commission. This was the agency that facilitated the transfer of a very great proportion of the agricultural lands of Ireland from the landlords to the people following the Land War, in which Parnell had been the leader. The time came when Uncle Tommy could afford to own a good-sized farm himself. He stood loyally between a multitude of his female relations and the collapse of their financial resources. While carrying everyone’s burdens Uncle Tommy remained somewhat aloof and managed to keep us children a little afraid of him. He was an excellent farmer, and a public-spirited man, very serious-minded, always working, and one of the first to persuade famers to organize in their own interests. When he was drowned in the Leinster1 in 1918 the farmers of Wexford put a very fine monument on his grave in Glasnevin.

The Esmonde family was in essence West British. My mother, with her three sisters and only brother, had a happy, carefree childhood, but the letters that passed between their elders were full of anxieties occasioned by the poverty that crept on them slowly, but relentlessly. None of them had any training that would enable them to mend their fortunes; all had been brought up in a world of privilege and leisure. The family held themselves detached from the nationalist politics of Sir Thomas Henry Grattan Esmonde MP – the head of the extended family, who was Mother’s first cousin. Sir Thomas, who often included ‘Henry Grattan’ in his name, was pleased as could be to be the grandson, through the female line, of the Irish patriot Henry Grattan – a distinguished Liberal in the old Protestant parliament (abolished by its own corrupt Act in 1801). Thomas Esmonde’s career in the House of Commons started under Parnell and lasted until we, of Sinn Féin, defeated him in the election of 1918. When I remember him first, he was a member of the party that John Redmond2 gathered together to heal the Parnell split. It was an oft-repeated family story that my grandmother wept with shame when Sir Thomas actively worked in favour of the tenants and against the interests of her friend and neighbour, the landlord George Brooke, during the No Rent campaign in the 1880s.

When we settled in Wexford, Granny was still mistress of Ballycourcey. She had retired to an armchair and put a lace cap on her thinning hair from the age of about fifty. Whatever current small dog dwelt in what must have been the supreme comfort of her floor-length skirts. She was attended by the two unmarried aunts, Millie and Zephie, and several maids. When granny went out it was always in the phaeton. This was a low, four-wheeled, open-sided carriage. The animal I remember her driving was Synx, an old racehorse retired from Ballinkeele Stables, owned by her cousins. Synx was so big and the phaeton so long that granny could not turn on ordinary country roads. It always exasperates me now to hear people talk about the dullness of country life!

The news came from The Irish Times in Dublin and from the local newspaper, and most memorably through the servants. ‘Maggie Brady says, so it must be true’ clinched many an argument. Maggie was pure gold and the talented wife of a farm labourer. There was no extra work she would not undertake if it would help to keep food on the table for her large family. Maggie was up to date in all things, trying out every new piece of advice offered by Miss Slattery – the poultry instructress who travelled the whole of North Wexford, driving her pony one day, and bicycling another. Maggie had honey, eggs and poultry in her ass car when she went to Enniscorthy every market day. In her spare time she came to help with our washing or butter-making, made cakes and brought us all the news. I never remember a time when she was not working. When rebellion arrived Maggie was devotedly Republican, and any matters or emergencies that came her way were certain to be handled with intelligence and without fear. But Maggie Brady had a bad old age. The Easter revolution of 1916 gave great joy and hope to the poor; afterwards, when there was no longer any need to stop for assistance, men in big motor cars went past those doors, except, perhaps, at election time.

In the long winter evenings in the drawing room at Ballycourcey we grouped around the little pools of light from two or three oil lamps. It seemed to me that we spent a great deal of time mending the woollen or lisle stockings, which made small resistance to our active toes and required much darning. By evening too, the elders of the family were finished with The Irish Times and our turn came to read it. I began to follow affairs outside the home.

We obtained most of our fun from riding and hunting. This was always supposed to pay for itself and my aunts tried their best to make pin money through occasional horse deals. This business was often spoiled by Uncle Tommy, who scorned the old established conventions, whereby it was ‘up to’ the buyer to carry his own share in valuing the beast, and bargaining about the price. Uncle Tommy always told the truth, and nothing but the truth. But this adherence to truthfulness only made the other side suspicious that some further defects, other than those that had been stated, were present. When Uncle Tommy pointed to the animal’s hock and foretold the probability that a curb or a spavin might develop there, this was a thing the dealer had, of course, spotted from the first glance; reference to the weakness only made the buyer think that his attention was being diverted from the possibility that the horse was a windsucker or a whistler. Many good farmers were breeding half- or three-quarter bred hunters from their Irish draft mares. Some had thoroughbreds. My Aunt Zephie was a great judge of horses and always hoped to find an exceptional young horse. In one of her last bids for fortune, Zephie managed, with her last hundred pounds, to get ‘on the turf’ as an owner of two famishing grey racehorses. One broke its neck training and the other was placed in the Grand National more than once, and afterwards sold to the States – but all successful things happened after circumstances had compelled her to sell.

Aunt Millie was an artist with paint and brush but devastating with hammer and nails when she attempted to repair some shattered fragments of antique furniture, bought for shillings at auction. She drove a beautifully sprung low gig, painted blue and black, with bells on the pony’s collar. Millie bred Pomeranians, or sometimes spaniels, for sale; but when the puppies were reared she was too kind-hearted to sell them, except to homes where she knew they would be well treated; but there, alas, the money would often be as scare as it was with us – so finances had a way of not working out. Millie was a wasted artist, who would certainly have developed her talent if she had ever in her life been able to support herself away from home. She was selflessly generous – one lovable individual among the millions of good women who got no chance to blossom in life. Millie had a great sense of humour and had many a good story, which she told with an array of gesticulations. Her stories were always short and crisp, as were her comments when we came into the years when the Volunteers3 began to organize. The fashion for brown suiting, something like the colour of shoe polish, seemed to be peculiar to the Volunteers. I remember Aunt Millie noted this, when she made a remark out of the blue one evening, as we were all gathered around the oil lamps in the dining room at the never-ending job of mending stockings. ‘Tommy Brady is wearing a chocolate suit and he is walking very straight,’ she said. Millie said no more but we all knew what she meant – that Tommy, who was Maggie Brady’s son and one of my Uncle’s trusted farmhands, was now a member of the Volunteers.

1 RMS Leinster was an Irish ship operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company, serving as the Kingstown (now Dun Laoghaire) to Holyhead mailboat. On 10 October, bound for Holyhead, the ship was torpedoed by a German submarine. The Leinster sank just outside Dublin Bay. There were 813 people on board and 569 were lost – the greatest ever loss of life in the Irish Sea.

2