8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

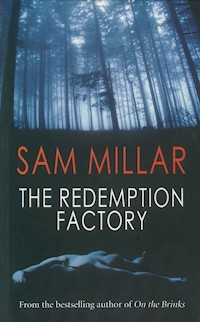

- Herausgeber: Brandon

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Security guards told the police that they were surprised by assailants who had somehow evaded the sophisticated security system. They could not say how many robbers there were…it appears to be one of the biggest robberies in U.S. history.' New York Times, front page In 1993 $7.4 million was stolen from the Brink's Armored Car Depot in Rochester, New York, the fifth largest robbery in US history. Sam Millar was a member of the gang who carried out the robbery. He was caught, found guilty and incarcerated, before being set free by Bill Clinton's government as an essential part of the Northern Ireland Peace Process. This remarkable book is Sam's story, from his childhood in Belfast, membership of the IRA, time spent in Long Kesh internment camps and the Brinks heist and aftermath. Unputdownable.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Reviews

“On The Brinks tells the story of an IRA activist imprisoned in the worst jails in Ireland, prior to one of the most famous robberies in American history. It this were fiction, it would be an excellent thriller, but it’s a true story, sustained by terrific writing.”Rolling Stone

“The indomitable Irish. On The Brinks is an amazing book built in two stages. Belfast, firstly, New York, each other. Two cities for two extraordinary lives. The story of those years is terrible humiliation, torture, acts of barbarism, man reduced to the level of a beast. Between Nazi concentration camps and gulags, Long Kesh finds its place among these horrors.”Le Figaro

“The life of Samuel Millar is worthy of an extraordinary film noir. And for once, the expression is not overused.”Le Parisien

“This man [Millar] is a true force of nature … with a strong will, a spirit unswervingly tough. On The Brinks is a piece of history narrated with humor, humility and simplicity. How can such a combination be possible? Yet it is true and an incredible story of Sam Millar, the indomitable Irish. Grab a copy now.” Corine Pirozzi, Huffington Post

“Cleverly structured as a succession of short, incisive chapters, the earthy titles despite the darkness of the story, the story grabs us from the very first lines. Humorous and self-deprecating … you are insured of a terrific and poignant read.”La Croix

“Security guards told the police that they were surprised by assailants who had somehow evaded the sophisticated security system. They could not say how many robbers there were … it appears to be one of the biggest robberies in U.S. history.”New York Times, front page

“Michael Mann’s Heat meets In the Name of the Father. Powerful …”Village Voice, New York

“Naked … for years on end in a freezing cell … beatings … whatever … Millar went through it all.” Pulitzer Prize-winning author William Sherman, Esquire magazine

“… fascinating …” “Dateline NBC”, New York

“His extraordinary life …”Irish America magazine

“One of the most powerful thrillers of the year.” Olivier Van Vaerenbergh, Le Vif, Belgium

“A book that will become a classic …”Irish Herald, San Francisco

“While most writers sit in their study and make it up, Irish crime writer, Sam Millar, has lived it. Read this remarkable book and see how.” Cyrus Nowrasteh, award-winning writer/director, Warner Brothers

“Powerful. Brilliant. On The Brinks is the kind of book all writers wish they had written – but thank the gods they didn’t have to live it! Millar’s the genuine tough guy personified who makes all other crime writers look like wimps.” Jon Land, New York Times bestselling author, Betrayal: Whitey Bulger and the FBI Agent Who Fought to Bring Him Down

“Mesmerizing and fascinating, On The Brinks is one of the most revealing and powerful memoirs you will ever read.”New York Journal of Books

“Hollywood couldn’t have done it better.”Irish Voice, New York

“… many twists and turns … perfect for a film …”Irish Times

“His brilliant memoir, On The Brinks, is a tale of surreal childhood in Belfast, of years of horror and torture and brutality in Long Kesh … The title of the book is testament to the author’s blackest humour which courses through the dark red memories of prison torture …”Irish Examiner

“By any standards Sam Millar has led a remarkable life. This memoir divides comfortably between the North [of Ireland] and New York. Millar’s vivid recollection of privations withstood during the blanket protest offers grim testimony to the limits of human endurance. Like others around him Millar would not be broken, even when political conviction was reduced to dogged resistance against a repressive prison regime. He then emigrated to New York, worked in illicit casinos. The American chapters unveil a gambling underworld run by New York’s Irish gangs. The empire wasn’t built to last but Millar eyed a much bigger prize … teaming up with an associate to rob $7.2 million from the hitherto impregnable Brinks Security operation in Rochester. It was a daring and bloodless heist … No one can dispute Sam Millar is an incredible survivor. Most certainly, a life less ordinary … compulsive reading …”Irish Independent

“Incredible … a masterpiece. A story Millar details in breathtaking panache.”Verbal Magazine

“His memoir, On The Brinks, has all the makings of a Hollywood blockbuster … cool narration of a life on the edge … he has a distinctive style and a compelling story. With the right marketing, this book will become a bestseller.”Books Ireland

“Millar takes the reader into the centre of one of the biggest robberies in US history. An extraordinary book … a gripping story of his life in prison to best-selling author … readers of On The Brinks will be on the edge of their seats waiting for another from Millar …” Books, Belfast Telegraph

“Once you put On The Brinks down, you will immediately pick it up again. Breathtakingly honest … a compelling tour de force …”Irish News

“Sam Millar is a fascinating guy. One of Ireland’s top crime writers … On The Brinks is an electrifying memoir …”Irish World, London

“An extraordinary life … a terrific book – absolutely.” Pat Kenny, TodayWith Pat Kenny, RTÉ

“Pat Kenny on RTÉ Radio 1 was positively revelling in the presence of Belfast writer Sam Millar and his memoir On The Brinks. It wasn’t too hard to hear why … we remain unused to hearing such conviviality from Kenny, or indeed most other RTÉ presenters … Kenny will be kicking himself that he hadn’t saved this for his Late Late Show …” Harry Browne, Radio Review, Irish Times

“A remarkable life by any standards … a fascinating read …” Mark Cagney, TV3

“On The Brinks is a tremendous read. The treatment of character is tremendous and the narrative is entirely gripping. The style is a well-controlled first-person telling which could very well not work if you were not so sure of what you are about. It belongs in the wider sense to the same literature as On Another Man’s Wounds, or rather the sequel The Singing Flame.” Dr Bruce Stewart, The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature

“On the Brinks is compelling and powerfully written with a style that makes it hard to put down … it is Millar’s ability to give a detached view of the brutalities and mistakes of his own life that makes On the Brinks read more like a work of fiction than the memoir it actually is.”Irish Emigrant, Book Review

“On The Brinks is an epic tale … his amazing life story … Millar is a great story teller who takes us right into the darkest recesses of his mind … gripping as he gives readers a rare insight into the US system of justice … an extraordinary journey … I have read many accounts of the H-Block/Blanket Protest, but Millar’s intensely personal account of the routine deprivation, brutality and isolation is by far the best I have read to date.”North Belfast News

“A masterpiece. Make no mistake about that.”Andersonstown News

“Millar who is wrongly imprisoned for being part of an ‘illegal organisation’ is sent to the notorious fortress boasted by Thatcher as the ‘H-Blocks’. In On The Brinks we encounter some of the most inhuman acts of this century, as we follow the plight of the prisoners, their hardship and their horrific human endurance. Even though Millar describes these times in a brutal, honest and disturbing way, he also exerts humour which takes your mind off the brutality for a moment and creates a perfect juxtaposition. On The Brinks deals with human suffering and endurance which is so horrific it makes it hard to believe that it actually happened. It is Millar’s ability to relieve his suffering in such a brutality honest way that gives the book its real strength. Emma Horgan, The Voice

“A remarkable life … reads like a movie script … an amazing story … riveting.” Marty Whelan, Open House, RTÉ

“It is not often that a reader is fortunate enough to strike gold and come across a gem of this quality. On The Brinks is one that reviewers sometimes take to awkwardly describing as unputdownable. That rings as gawkily as unletgoable. A term like ‘stunning’ better fits the elegance with which Sam Millar conveys his story. His early life prior to going to jail is fascinating for his story telling ability alone. This former republican prisoner came up on the outside track unnoticed, eventually leaving his literati comrades watching the dust kicked up by his heels. Riveting … brilliant …” Dr Anthony McIntyre, Good Friday: The Death of Irish Republicanism

“Read this brilliant memoir from the creator of the equally brilliant Karl Kane books. A review couldn’t do it justice. It goes from Millar’s depressing and oppressed childhood as an Irish nationalist in the North of Ireland, to his long stint in prison where he is tortured for his political activities, to his time in New York as a blackjack dealer, and finally to his famous caper – a Brinks robbery in upstate NY. Goes from sad to funny to exciting. Good advice: don’t expect an old van to start with eight million dollars in the back – it’s heavier than you think! Absolutely unputdownable!”Noir Journal, USA

Dedication

I dedicate this new edition of On The Brinks to the memory of my father, Big Sam, a rebel and nonconformist in the true sense of the word. And to my mother, Elizabeth. The dark place has finally gone, and redemption has been granted to both of us.

An Appreciation

Many thanks to my family circle here in Ireland as well as Europe, Argentina, Australia, Canada and USA, and all my relations and friends for their support of my previous books. To all the clans: Millars, O’Neills, Morgans, Clarkes and McKees. A special thank you goes to my brothers and sisters, Mary, Danny, Joe and Phyllis. To all those who helped On The Brinks win the prestigious Aisling Award, and making it a bestseller. A special mention to Dr Roger Derham, Brenda Derham, Valerie Shortland and all at Wynkin de Worde, for having faith in the original book, and the dedication and kindness you granted me. Also, Gaye Shortland, author of Rough Rides in Dry Places, for leading me to their doorstep. Also, The O’Brien Press for bringing the book to a new generation of readers, and special thanks to Eoin O’Brien for his meticulous eye to detail. Finally, and most importantly, a big kiss and thank you to my best friend and wife, Bernadette, and children, Kelly-Saoirse, Ashley-Patricia, Corey-Joseph and Roxanne. Now that On The Brinks is ready for my publisher, once again I no longer have an excuse not to cut the grass, make the tea, see the latest movie, go for a walk, stop drinking so much damn coffee …

A writer without interest or sympathy for the foibles of his fellow man is not conceivable as a writer. Joseph Conrad

We have always found the Irish a bit odd. They refuse to be English. Winston Churchill

Contents

Introduction

By James Thompson, critically acclaimed bestselling American author, Snow Angels and the Inspector Vaara series.

On the Brinks is a story of the Old Gods. The Fenians. Bran, Sceolan, Lomair, others. Sam Millar. Belfast boy. IRA man. Political prisoner. Long Kesh. The Maze. The H Blocks. The protests. On the blanket, freezing and naked, covered in human filth. An engineer of the largest prison break in European history. The mastermind behind the fifth-largest heist in US history.

Millar is our Oisín, and like Oisín, when he entered the gates of Long Kesh Prison, three hundred years of age fell upon him. He suffered unimaginable torment for his beliefs. He could have stopped that torment at any time with two simple words. ‘I relent.’ But he never uttered those words, and relent he never did. To read On the Brinks is to feel shame. To feel shame because almost all of us know, deep in our hearts, that we would have relented within hours, that we would have lacked the inner strength of will to stand up for our beliefs, the courage of our convictions, while our minds and bodies were ravaged, year after insufferable year. To feel shame because we belong to a race which inflicts such savagery upon its own kind. Yet On the Brinks leaves us with hope, because no manner of brutality led to the destruction of Millar’s spirit. Despite all, his remains a powerful voice today.

Well over a hundred years ago, in his poem “The Wanderings of Oisín”, William Butler Yeats summarised the story of Millar and those that suffered with him, predicting it as if he were Nostradamus peering into still water and watching the future of Ireland unfold. I leave it to Yeats, in his conversation between Oisin and St Patrick, to tell the tale.

James Thompson

Prologue

Hollywood couldn’t have done it better. Irish Voice,New York

Security guards told the police that they were surprised by assailants who had somehow evaded the sophisticated security system. They could not say how many robbers there were … it appears to be one of the biggest robberies in U.S. history.New York Times,front page

When I met him later that night, he was smiling, hand outstretched, as if greeting me for the first time in years.

“Don’t say a word in the car,” I whispered, a plastic grin on my face. “There’s a possibility of it being bugged.”

We drove down Lake Avenue, towards the beach, in total silence.

I parked the car behind some sand dunes, and then proceeded to remove a few Buds from the back seat.

Not too far away from us, a young couple were sitting on a grassy hill, eating greasy sandwiches, watching people on the beach beginning to pack and leave.

It was late evening but the heat was still horrendous. A fleshy-coloured moon dangled in the late sky, hanging like unsacked testicle. Crickets were making small talk and mosquitoes bit on my ears as I watched calmness come to splintered waves. A seagull hovered effortlessly in the thick air, killing itself laughing. Later, I would remember the albatross in the Ancient Mariner. Much later, I would remember a seagull by the name of Stumpy in Long Kesh prison …

When we were out of earshot, I quickly came to the point. “How’d you like to make some serious money?”

“How serious?” he asked, taking a slug of Bud, balancing his words carefully. He remained noncommittal.

“Maybe a million,” I answered nonchalantly, placing the beer to my lips while watching his reaction.

The Bud hit the back of his throat, making him cough and splutter.

“Are you shitting me?” he said, wiping the spillage from his chin.

“This is our target,” I said, kneeling on the sand, ignoring his question.

With my finger, I started to draw a deep wound in the sand. Before long, I had sketched the rough layout of a bird’s-eye view of the building in question, a collage of rectangles and squares. I didn’t speak. Even when the waves slowly crept in, erasing my work, I said nothing, waiting for it to disappear.

“Let’s go,” I eventually said, brushing the sand from my jeans while rays of rolling water embraced the sand, kissing it before retreating like a chased child.

We began walking along the beach, whispering into each other’s ears like lovers on a first date. An old lady walked by, exercising her dog, her eyes never leaving us. Shaking her head with disgust, she watched us disappear behind sand dunes, as if witnessing some sort of secret, sexual encounter.

When the time came, I looked back on that eventful day, realising I had been shitting him. It was more than a million. A hell of a lot more.

American history was about to be made, and I was the one going to pen it …

PART ONE

BELFAST BLOODY BELFAST

I care not. I have been stripped of my clothes and locked in a dirty, empty cell, where I have been starved, beaten, and tortured, and like the lark I fear I may eventually be murdered. But, dare I say it, similar to my little friend, I have the spirit of freedom that cannot be quenched by even the most horrendous treatment. Of course I can be murdered, but while I remain alive, I remain what I am, a political prisoner of war, and no one can change that.Bobby Sands

In Britain, we are often told there is an Irish problem, but the truth is there is a British problem in Ireland. Occupation failed, partition failed, Stormont failed, direct rule failed, strip-searching, plastic bullets and the H-Block failed because they were all designed to retain British rule.Tony Benn

CHAPTER ONE

The House

APRIL 1965

And this also … has been one of the dark places of the earth.Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

They fuck you up, your mum and dad. They may not mean to, but they do.They fill you with the faults they hadAnd add some extra, just for you.Philip Larkin, This Be The Verse

I was born in Belfast and lived in Lancaster Street, a street whose most famous sons included world boxing champion John Joseph “Rinty” Monaghan, and renowned Irish artist John Lavery. Among Lavery’s many famous paintings was that of Kathleen Ní Houlihan on the first Irish Free State bank-notes; his wife, Hazel, was used as the model.

After moving from his humble abode in the street, it wasn’t too long before Lavery became internationally famous. He moved to London, where he subsequently lent his palatial house at Cromwell Place in South Kensington to the Irish delegation led by Michael Collins during negotiations for the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921. After Collins was killed, Lavery painted a portrait of him, titled Michael Collins, Love of Ireland. This despite rumours that Collins was having an affair with Hazel while staying in London.

Lavery may well have been good enough company for Collins, but he sure as hell wasn’t good enough for our wee street. We never spoke much of the gifted man, for the simple reason that he committed one of the most unpardonable sins known to us: accepting a knighthood from the British Empire. From a street that would see three-quarters of its male population interned without trial, or sent to Long Kesh by the infamous non-jury show-trials of Diplock, it was easy to understand why.

Lancaster Street had a history of sectarian riots, dating back as far as anyone could remember. Orange Order mobs, accompanied by the peelers, attacked it frequently, usually leaving gallant defenders of the street wounded or dead. In September 1921, the New York Times reported on page five that: SHOOTING IS RESUMED IN BELFAST STREETS: Boy Dies of Wounds, Making Total Dead 18.

The street was named after a Quaker school and educational system founded there, but those of us living in the street much preferred the story that it was named after Burt Lancaster, the brilliant American actor whose grandparents originated from Belfast before immigrating to America.

My mother, Elizabeth, was a workaholic, perpetually scrubbing and cleaning. She always smelt of Daz, bleach and the carbolic soap that stained her hands the colour of raw wounds. While my father, Big Sam, worked as a merchant seaman, she ran a semi-boarding house that contained the grand total of one lodger. She never made a penny from the house and was perpetually in debt because of it. Her purse was testimony to that. It was a working-class purse. Fat. Fat with the pain of pawn tickets and IOU’s. Fat with poverty, like the false swelling bellies of starving children in far-away Africa.

That night before my father’s departure to sea, they were arguing over her loneliness and his need to be free.

Silently, I crept to their bedroom door, tapping meekly on it, hoping neither would hear. This was my way of clearing my conscience, the rationalisation of a coward trapped in his own paralysis. The door never opened, and I managed to quickly slither back to bed, relieved, dreading the distorted looks on their faces, knowing they would have hated me for what I knew.

The next day, I returned home from school with my friend, Jim Kerr. We kicked at an old ball we had found on the way.

“Will I call for you after supper?” he asked, while heading the ball expertly.

“I’ll call for you,” I said, dreading the thought of my mate seeing what I knew was waiting for me.

“Okay. Make sure you call.” He kicked the ball ahead, and rushed after it, probably thinking he was Georgie Best.

When I entered the house, my mother was sitting on the sofa, smiling strangely to herself. She stood, and then leaned to kiss me, but I pushed her away, betrayed.

“You’ve been drinking,” I accused. “And after all you said?”

Her skin always glistened in the dull sunlight as the alcohol rose to the surface, seeping through her pores. She smelt strongly of mints – a smell I came to dread – using the sweets in a vain effort to camouflage the horrible stench of dead leaves that settled heavily on her breath; of brandy in all its degrading cheapness. It never failed to transform her into a mumbling, sobbing wreck.

“Your father’ll be home next month, Son,” she said, wiping her flour-covered hands nervously on an apron. The apron was covered with windmills and trumpet-headed daffodils swaying in the breeze. “He doesn’t need to know, does he, about the wee bit of drinking?”

Already her words were coming out slurred. Soon she would start crying, telling me how lonely she was; how my father was to blame, for being away so long at sea.

I hated her when she was like this. Did she not know how humiliating it was for me to sneak into the off-license, hoping no one – especially my mates – would spot me? To add insult to injury, the man behind the counter always gave me that knowing, devious wink that said: Your ma’s secret is safe with me, wee Sammy. Don’t you worry your wee head. His words were slippery, like a snail captured by the sun. I would remember him and his sneaky face, years later, even though he no longer existed in this world.

“You won’t tell your father,” she repeated again, fearful of my silence.

“Leave me alone,” I said.

She smiled sadly, attempting another kiss, burning my mouth with the brandy wetness on her lips.

“Keep away from me! You’re disgusting!” I shouted, pushing her back onto the sofa. “I hate you when you’re like this. I’m telling Dad, when he comes home!”

But when she sobbed those terrible sounds, her hands covering her face with shame, I knew I would never tell.

I placed my hands on her head, hoping to soothe her. “Don’t cry, Mum. I won’t tell him.”

But she couldn’t look at my face; simply wanted me to leave the room. When I did, she continued her mumbling, whispering, “Your father need never know …”

As time progressed and her mental health deteriorated further, she began picking at the wallpaper with her fingernails, leaving them a bloody mess and the walls devastated like leprosy. Neighbours began to talk about her, about the state of the house.

It was shortly after that she solved it all, choosing to live in the shadow of the dead in exchange for the debt of the living. And while we slept, the rain against the window filled her head with a reservoir of eerie dreams, easing the pain that had crushed her for years.

CHAPTER TWO

Leaving

MAY 1965

The thought of suicide is a great consolation: by means of it one gets successfully through many a bad night.Nietzsche, Jenseits von Gut und Böse

Between the idea, And the reality, Between the motion, And the act Falls the shadow.TS Eliot, The Hollow Men

As a child, Saturday mornings always attracted me to the local pub, at the bottom of our street on York Street. Outside the pub, crates of empty Guinness bottles were pyramided against the wall, smell fermenting in the early sun. Their contents were gone with last night’s dreams, leaving only a few teardrops of the black stuff glimmering at the bottom of each bottle. Flies, vile and lazy, nestled drunkenly on the bottlenecks, buzzing angrily at their hangovers.

“Whaddye want?” asked the barman, suddenly appearing at the doorway of the pub, scrubbing brush and bucket in his large, working-class hands.

“Nothing,” I replied. “Just looking.”

“Then go look elsewhere.”

He hated anyone watching him struggle with last night’s vomit. It permeated the ground, staining it like great maps of the world.

“Not want me to kill the flies for you?” I asked, showing him my Irish News rolled into a peeler’s baton.

He stared at me for a few seconds, then skyward for divine guidance.

“Okay … but don’t eat ’em,” he grinned, but I only nodded solemnly and turned to the task of transforming fat-bellied flies into perfect inkblots of death.

A dog came to watch, but soon became bored, and began chasing itself in an odyssey of arse-sniffing circles, as if fascinated by its own hairy hole.

Sometimes, if the barman remembered, he brought me a Coke, making me swear to Our Lady that I’d return the empty bottle. I always did, no matter how much I wanted to keep it for target practice in Alexander Street’s derelict houses.

The dog suddenly began sniffing suspiciously at a dead sparrow on the ground. The bird’s anorexic legs were protruding upwards, like miniature branding irons towards the sky.

“Can ye hear ’em?” asked the barman as he threw a bucket of steaming hot water and disinfectant about the pub’s entrance. “Well? Can ye?”

Of course I could hear them. The lexicon of Clockwork Orangemen floating acoustically from Clifton Street, where they had gathered en masse below the pigeon-stained statue of King Billy. From there they would march to the Glorious Field, unfurling their banners of intolerance and hatred, flanked by benign old ladies resplendent in their Union Jack dresses and Fuck The Pope hats.

As the Orangemen approached the shadow of Saint Patrick’s Church, it was as if they had suddenly become possessed: leaden faces swelling with anticipation; eyes bulging like ping-pong balls, and thick, ruddy necks trafficking with corduroy veins the size of football laces exposing their congenital abhorrence of all things Catholic.

My father always said that Orangemen were full of sour grapes and whine. It was hard to argue against his logic, because he would know, of course, his father being a leading Orangeman …

* * *

My grandfather, Alexander Millar, came from a staunch Protestant family whose loyalty to God and Ulster was never questioned. He marched to the Field every Glorious Twelfth, and no doubt had his eye on becoming Grand Master, with great visions of riding down Clifton Street atop a white horse like his hero, King Billy, long hair cascading like singer, Tiny Tim.

He was one of the first to sign the Ulster Covenant, at City Hall, 28 September 1912, protesting against Home Rule. Over half a million men and women signed the Ulster Covenant, and the parallel Declaration.

It was rumoured he signed it in his own blood. Unfortunately, that’s all it was – a rumour. Contrary to all the urban legends surrounding the signing of the Ulster Covenant, only one signature was ever dipped in blood, that of Frederick Hugh Crawford, who was to become the Ulster Volunteers’ Director of Ordnance.

Because of his strong Protestant beliefs, Catholics meant little to my grandfather. Their strange beliefs and customs were difficult to comprehend. They were an invisible people. There, but not really there; moving, but going nowhere. He believed the dogma that Catholics in the North had only themselves to blame for their dire situations of abject poverty and unemployment, and that, perhaps, they didn’t really want to work. They bred too quickly, also, and didn’t believe in controlling their sexual urges – or at least using conventional methods to mitigate their effects.

At the Somme, he was badly wounded, and received three medals for bravery. Tragically, however, two of his brothers were to die on the same bloody field in France, fighting for an empire I would later fight against.

Despite his Orange Order credentials, he didn’t hate Catholics, but he certainly had no love for them. He was a very tolerant person, my grandfather. As long as Catholics knew their place and didn’t bother him, things would be fine. That was until he actually met a Catholic and committed the ultimate crime of falling in love with one.

My grandmother, Elizabeth O’Neill, was a Catholic, from the South. A fiery woman, she took nonsense from not a soul – including her soon-to-be husband.

Elizabeth quickly established the law the first time Alexander proposed to her: “Any children that God may bless us with, will all be brought up Catholics.” No ifs, ands or buts. “If you don’t like it, end this right now.”

Had he ended it there and then, of course, my life would no doubt have taken a different course. Instead, he decided if not to actually become a Catholic, to at least help them on their way, by fathering almost a dozen little Millars, outdoing “The Waltons” by at least two.

Most of the children gave Elizabeth or Alexander little or no trouble, with the exception of son, Danny. It was rumoured that he had left home secretly to become a priest, rather than offend his father by becoming one in Belfast, causing more embarrassment for Alexander’s side of the family. The truth was a bit more complicated, and slightly more interesting. Prior to his leaving, Danny was having an affaire de coeur. Unfortunately, the woman was married. Worse, her husband was a member of the RUC.

Perhaps Uncle Danny had been watching too many romantic Errol Flynn swashbuckling movies, but in a bold – some would say foolish – move, he stole the man’s gun and shot him, in the privates and privacy of his own home, which can be quite sore, apparently. Hauled off to jail, court papers state:

MAGISTRATE MR P.J. O’DONOGHUE R.M. and other MAGISTRATES:

DANIEL MILLAR of 18 LANCASTER STREET was charged with having on MONDAY in his possession or under his control a WEBLEY REVOLVER and 24 rounds of ammunition with intent to endanger life or enable other persons to do so. He was further accused of having an explosive substance in his possession for an unlawful object and without holding a firearms certificate, and with occasioning actual bodily harm to WILLIAM MELI. DISTRICT INSPECTOR FERRIS prosecuted and MR G. MAGEE defended. DET SERG W.J. McCAPPAN gave evidence that he went to the residence of the accused and told him that he called to see him regarding the shooting incident with a revolver that had occurred between himself and WILLIAM MELI at ALEXANDER STREET on MONDAY. He replied: “I know nothing about it.” On being cautioned he said that he had given it away to a boy, and that he could not give his name, as he lived a long way from LANCASTER STREET. He then requested witness to accompany him to his bedroom where he took the revolver from his suitcase, which was underneath his bed. He handed witness the revolver, which was loaded in six chambers. He also took from the suitcase a box containing nine live revolver cartridges and handed them to witness also. When charged at GLENRAVEL STREET POLICE STATION, accused said that: “I did not mean to do any harm with the revolver – it was just a practical joke.” WILLIAM MELI said he knew of no reason why the accused should do him any injury. DANIEL MILLAR was released on bail for a week, and told to report to GLENRAVEL STREET POLICE STATION.

It was practically unheard of for a Catholic to have bail granted for such serious charges in the sectarian satellite, but granted it was. Some people said my grandfather reached out to old friends in the Orange Order, asking them to persuade the judge to grant bail. Some say William Meli dropped the charges, fearing a scandal and becoming a laughing stock for being shot in that most private of places. Whatever the reason, money was raised, and within that week of freedom, Uncle Danny disappeared from the land of Ireland forever, ending up on the streets of Buenos Aires, where he soon discovered that life really is a box of chocolates. Life suddenly got a lot sweeter for Danny, when he married into one of the wealthiest families in Argentina, makers of fine chocolate.

Ironically, years later, when our house was searched for guns belonging to the IRA, it was my grandfather’s Orange sash hanging proudly on the wall beside portraits of the Pope and John F Kennedy that not only confused the raiding party of peelers, but made them rethink their strategy and offer profuse apologies for searching the house of a true son of Ulster. They quickly abandoned the search, empty-handed.

* * *

“Bastards,” said the barman to himself. “Hope to fuck a few of ’em die of a heart attack in this heat. That’ll take the sectarian marching out of ’em. Orange bastards.”

Just as the dog bowed its spine, preparing to leave its shitty mark, there was the sickening sound of wood on bone, as the barman cracked the unfortunate creature over the head with his scrubbing brush.

“Get, ye dirty bastard!” he screamed, sending the injured dog running for its poor life. A few seconds later, he spat, just where he had spent all morning scrubbing, before walking back to serve a customer tapping an empty glass annoyingly against the counter.

Peering in the window, I could see the counter lined with pints of perfect Guinness. Rivulets of condensation were forming on the fat bodies of the pints, sitting there, sweating tantalisingly, tight, like a synod of clergy in secretive discussion.

Suddenly, in the window’s reflective glass, I spotted a familiar shape jumping up and down, directly behind me.

“Yer da’s lukin’ fer ye, Sammy!” screamed Gerry Green, waving his hands frantically, from across the street.

There was nothing Gerry loved better than bringing bad news. The more distressing the news, the happier he became. He was the local bully, but an unusual one because he had a conscience and only hit you when you deserved it – which was usually twice a day, except on Fridays when he got his pocket money. He never touched you on Friday. A decent bully, I suppose. He was three years older than me, with glass-cutting blue eyes. A family of pimples inhabited his entire face. He’d no doubt be a horror to look at in later years.

“Yer da’s shoutin’ all over the place like a mad man fer ye. Luks like yer in fer it!” he hallelujahed, as I crossed over to the other side of the street.

To see someone “in fer it” could bring tears of joy to Gerry’s blue eyes. He was practically pissing himself with happiness escorting me back down Lancaster Street, fearful I would escape whatever justice awaited me.

“Luks like yer gonna get a good boot up the arse, Sammy,” said Gerry, encouragingly, marching triumphantly behind me.

From a distance, I could see the towering and intimidating figure of my father, standing outside our house. As I neared, a rosary of knots formed in my stomach, warning me.

“Where’ve you been?” Dad was putting on his jacket, as he handed me a bag of fruit. His shoes were gleaming, as usual, because he was a great believer in the Cherry Blossom legend: Ashine on your shoe says a lot about you. “Didn’t I tell you not to be going away from the door?”

“I was just helping the barman kill flies.”

“You shouldn’t have left the door. When I tell you to do something in future, make sure you do it. Now, hurry up and get your coat and let’s get going. We’re late.”

Gerry was devastated. I didn’t get a good boot up the arse. Not even a slap on the head. For a moment, I thought he would complain to my father about misguided leniency. Instead, he simply walked away, head down, despondent.

“For heaven’s sake, will you cheer up a bit?” Dad said, as we turned the corner of the Crumlin Road. “It’s the hospital; not O’Kane’s – not this time, anyway.”

O’Kane’s was the local undertakers, but as far as I was concerned there was little difference between it and the dreary wards of the Mater Hospital, which we entered twenty minutes later.

“How is she today, doctor?” Dad said, stopping beside the young doctor outside the ward.

“A slight improvement from yesterday, Mister Millar. We hope to give her soup, later. She had some tea last night, but couldn’t hold it down for long. I’m sure you appreciate that it’s a very slow process.”

A soft breeze suddenly began rallying the combined stenches of piss, vomit, disinfectant and the dry talc smell of death, filling the corridors and my nostrils with a debilitating dread of all hospitals.

Entering the small ward, a nurse escorted us to a bed at the end. The nurse looked sadly at me before moving on with the rest of her duties.

On the bed, my mother lay motionless, her pallid complexion as one with the linen sheets, making her almost invisible.

It wasn’t her first attempt at suicide, but it was her most imaginative as well as elaborate. Instead of simply opting for an overdose, she had decided to slash both her wrists also. This time she almost made it, having been pronounced DOA by the doctor on duty. Her effort was frustrated only by the attentive eyes of my older brother Danny, who, upon hearing the doctor’s verdict, became maniacal and demanded a medical miracle.

It worked. God granted the miracle. She would live to die another day.

I knew she could hear me whispering in her ear as my father sat silently, chained to the guilt of wasted memories that were cemented in the heat of anger and fury. “You could’ve waited,” I accused. “I told you my exam results were due and that I would do well. But you don’t care, do you? I hope you die, next time.”

She ignored me, feigning the death she had yet to perfect. A log, stiff with shame and loneliness. Suddenly, her exhausted eyes turned dark. The way a beetle’s shell looks when raindrops fall on it.

It was the last time I would ever see her, as she fled into shadows a few nights later. And when neighbours snidely insinuated she wouldn’t be back, I knew they were mistaken. They didn’t know what I knew: she had only smoked two of her Park Drive. She would be back for the rest.

But even the pictures on the wall knew better. The Sacred Heart became more melancholy, while the vulpine grins of the princes of Rome and Camelot mocked my naiveté. They knew.

Oh, what a fool I had been.

From that day, I could never listen to Middle of the Road’s classic wee number, “Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep (Where’s Your Mama Gone?)” without feeling sick to the stomach with anger and betrayal.

CHAPTER THREE

A Very Hot Summer

AUGUST 1965

Everything that deceives also enchants.Plato

And life is thorny and youth is vain And to be wroth with one we love Doth work like madness on the brain.Samuel Taylor Coleridge

A madness of sorts possessed Dad now that he was onhis own. For a while, things were great, as he pitied me more than himself. But as the cold reality began to bite at him, he slowly reversed his feelings in favour of himself, finding fault with everything I did. I had to run like hell when he sent me on an errand. He would time me, always criticising with a “what the hell kept you?” It would have made no difference had I broken the world record, it would still be “what the hell kept you?”

Of all the days I hated, Friday mornings, before school, were the worst, having to deal with George Flanders, the greengrocer from hell.

“How many, young Millar?” asked Flanders, a giant with tight clothes, lamb-chop side-burns, a ruddy complexion and an enormous nose that defied gravity. The kids called him Banana Nose. His eyes had the tight look of someone who scrutinised beaten dockets, hoping beyond hope. The same eyes could remove skin, burn you with their intensity.

“Fifty, Mister Flanders,” I squeaked, hating this part: the barter of apples from my father’s tree.

Flanders handled one of the apples, rubbing his thumb against the texture, before smelling it with his giant nostrils. “Four cabbages. Howsabouthathen?”

“My dad said five cabbages, four carrots and a quarter stone of blue spuds.” I always wished Flanders would speed it up, in case one of my mates came in for an apple, and ended up witnessing my humiliation.

“Ha! Yer da’s arse is out the window! I’m a greengrocer, but I’m not green.” Flanders laughed. He was now juggling some of the apples, like a clown, winking as he pretended to let them fall.

Dead, supine flies lined the window of the fruit shop like a contiguous military convey debilitated by superior forces, while their air-borne comrades struggled menacingly above, attached to flypaper, tearing off their own limbs. I would stare at the adhesive, fascinated by its struggling victims, trying in vain to detach themselves from the sticky graveyard. It reminded me of the currant buns sold next door in Mullan’s bakery. I had never tasted one in my life. Never would.

That’s life, I thought, one big sticky ending that comes to us all.

“Ye’ve caught me in a generous mood, young Millar,” Flanders said, his face a politician on polling day. “Four cabbages. And here’s some carrots as well.”

It was over. He had won. I had lost. As usual.

As I left his shop, Flanders handed me a pear. It was badly bruised and had his teeth marks in it. “Here, that’s for yerself. And tell yer da he’s gotta git up early ta catch me!”

I could still hear his laughter halfway down the lane.

“That’s all you got?” Dad said, looking on the exchange with disdain.

Why didn’t you go yourself? I would ask, in my dreams. Afraid of the humiliation?

But if Friday mornings were bad, Friday nights were a nightmare. I had to run to Peter Kelly’s for fish and chips. And even though I would run like a madman and the fish and chips would’ve burnt the mouth off him, Dad would still greet me with: “These are freezing. What the hell kept you …?”

As I ran, people would stare at me, as if I’d become completely mad. Despite this, I still couldn’t find the courage to refuse to run, in case I incurred Dad’s wrath. But all that was about to change, when one Friday night someone else’s madness intervened.

The line at the chippy snaked the corner, stretching all the way to McCleery Street. Everyone loved Peter’s fish and chips, so there seemed to be a perpetual queue at it, especially Fridays and Saturdays, when working-class people had some money in their pockets.

Dad’ll kill me, was all I could think of as I ran even faster to get my place in the queue.

“I watch ye every Friday night. Ye think ye are somebody, don’t ye?”

He was a bit younger than me. His face was filthy, as if a dirty rag had attached itself to his skin, sucking the life out of him.

I was so exhausted I could hardly breathe, let alone answer.

“What’s its name?” he said, running in perfect unison beside me.

“What? Get away from me, will you?” Everyone was watching the two of us.

“Yer horse, stupid? What’s yer horse’s name?”

I tried to ignore the head-case.

“They call my horse Silver. Just like the Lone Ranger’s,” he said, proud as a peacock up at Bellevue Zoo.

My chest was burning with exhaustion. I needed to stop.

“The great thing about Silver is that he’s invisible. I’m the only one who can see him.” Suddenly, he did a strange, jerking movement, before patting the neck of the invisible horse. “Easy, boy. Easy. No one’s gonna hurt ye.”

Ignoring the threat on my face, he continued talking.

“The great thing about Silver being invisible is when he shites all over the street. Nobody can see it, so they walk on it! I laugh when I see them walking into their houses, trailing Silver’s invisible shite along with them! And the smell! Worse than visible shite, I can tell ye! Everyone laughs at me, but I always get the last laugh. Don’t I, Silver?”

Without warning, he leapt two feet into the air, patting the nervous horse, reassuring it. “Easy! Easy, Silver. Good boy.”

Everyone was grinning at us, but before I could grab him he shouted: “See ye! Hi ho Silver, away!”

And away he went, slapping the arse off himself, jumping over bin lids and empty cardboard boxes.

That was it, I decided. No more running like a madman. Dad could do what he liked to me, but I’d been humiliated enough.

I was more than surprised when Dad didn’t force the issue and was quite proud of my stand. But pride always comes before a fall and a week later, to my horror, he enrolled me in the local boxing club, where I won many friends as a walking punch-bag.

It would be many months before I’d meet the Lone Ranger again. His face was a mask of sweat as he cleared three bins with ease.