7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

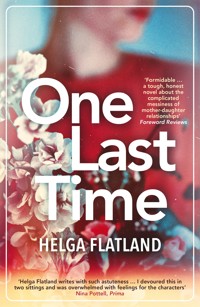

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Anne's diagnosis of terminal cancer shines a spotlight onto fractured relationships with her daughter and granddaughter, with surprising, heartwarming results. A moving, elegant and warmly funny novel by the Norwegian Anne Tyler. 'Helga Flatland writes with such astuteness … Her portrayal of a fractured family trying to cope through emotional personal circumstances was perfect. I devoured this in two sittings and was overwhelmed with feelings for the characters' Nina Pottell, Prima 'Sometimes you simply don't have words to express the beauty and experience of a book – this is one of them' Louise Beech _______________ Anne's life is rushing to an unexpected and untimely end. But her diagnosis of terminal cancer isn't just a shock for her – and for her daughter Sigrid and granddaughter Mia – it shines a spotlight onto their fractured and uncomfortable relationships. On a spur-of-the moment trip to France the three generations of women reveal harboured secrets, long-held frustrations and suppressed desires, and learn humbling and heart-warming lessons about how life should be lived when death is so close. With all of Helga Flatland's trademark humour, razor-sharp wit and deep empathy, One Last Time examines the great dramas that can be found in ordinary lives, asks the questions that matter to us all – and ultimately celebrates the resilience of the human spirit, in an exquisite, enchantingly beautiful novel that urges us to treasure and rethink … everything. For fans of Elena Ferrante, Maggie O'Farrell, Mike Gayle, Joanna Cannon, Sally Rooney and Carol Shields. _______________ 'The most beautiful, elegant writing I've read in a long time. If you love Anne Tyler, you will ADORE this' Joanna Cannon 'Flatland is hailed as "the Norwegian Anne Tyler", but, for me, she writes like Flatland, which is more than good enough' Saga 'A poignant and beautifully written story ... intimate, evocative and moving' Kristin Gleeson 'Helga Flatland possesses a pen made from fluent wisdom, subtle humour and elegance' Carol Lovekin 'Absolutely loved its quiet, insightful generosity' Claire King 'So perceptive and clever' Rónán Hession 'A thoughtful and reflective novel about parents, siblings and the complex – and often challenging – ties that bind them' Hannah Beckerman, Observer 'This is a super exploration of families that I'd urge you to read for the subtle prose, with well defined characters and a strong storyline' Sheila O'Reilly 'Love the sophistication, directness and tenderness of this book' Claire Dyer 'The most clear-eyed, honest, yet sympathetic examination of relationships that I have ever read' Sara Taylor 'The author has been dubbed the Norwegian Anne Tyler and for good reason … If you love books about dysfunctional families, you'll love this' Good Housekeeping 'In quiet prose, Helga Flatland writes with elegance and subtle humour to produce a shrewd and insightful examination of the psychology of family and of loss' Daily Express

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 381

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Anne’s life is rushing to an unexpected and untimely end. But her diagnosis of terminal cancer isn’t just a shock for her – and for her daughter Sigrid and granddaughter Mia – it shines a spotlight onto their fractured and uncomfortable relationships.

On a spur-of-the moment trip to France the three generations of women reveal harboured secrets, long-held frustrations and suppressed desires, and learn humbling and heart-warming lessons about how life should be lived when death is so close.

With all of Helga Flatland’s trademark humour, razor-sharp wit and deep empathy, One Last Time examines the great dramas that can be found in ordinary lives, asks the questions that matter to us all – and ultimately celebrates the resilience of the human spirit, in an exquisite, enchantingly beautiful novel that urges us to treasure and rethink … everything.

One Last Time

Helga Flatland

Translated by Rosie Hedger

In the middle of your life, death comes calling, Here to measure you up. You forget His visit and life continues. But still He sews your suit in secret Tomas Tranströmer

Tomas Tranströmer

CONTENTS

1

I bring the blade of the axe down on her neck. Drop the head into one bucket, the body into another, hear the way her claws scrape slightly against the plastic before silence falls once again. I head into the barn and fetch the next one, clutch her tight to my breast as I walk, feel her tremble there, the quiver of her pulse beneath her feathers, I whisper quietly to her before turning her over, holding her by the legs until she calms down. Quickly I lay her on the chopping block, stretch out her neck, deliver a hard blow to the head with the blunt end of the axe, and in one swift gesture I spin it around in the air and swing it back down again, slicing off her head with the axe blade.

I’ve forgotten to close the barn door, one of the hens has escaped and is standing in silence just outside. She gazes at me. She looks distraught, possibly confused, as if she can’t believe what she’s just witnessed, I feel for her, wonder if I should return her to the others and save her for last, or if she’ll simply wander around, dreading the inevitable for longer than is necessary. Gustav would have laughed at me, told me I’m crediting them with feelings they don’t have, feelings of my own.

‘Come on, old friend,’ I whisper, crouching down on my haunches, feeling an aching sensation in my knees, throughout my whole body, need to call Sigrid, take out the grain feed in my pocket, lure her in, she whips her head first to the left, then to the right.

I don’t even particularly like hens, and this flock has long since stopped laying, I’ve only kept them for nostalgic reasons – and to maintain the illusion of some sort of working set-up. A farm needs animals, Viljar had said when he was last here. I agreed with him to some extent, but keeping five hens that no longer lay for the sake of grandchildren who visit four times a year is no longer reason enough.

The hen can’t resist temptation in the end, wanders over and eats out of my hand. I stroke her feathers and let her finish the grain before butchering her.

2

‘Sigrid? Your mother rang,’ Aslak says as I step in the front door, he’s lying on the sofa with his back to me and picks up my phone as if to show me the conversation, but without turning to look at me. ‘Something about some hens, I think.’

‘What do you mean, you think?’ I ask, taking off my shoes and coat.

‘Well, it was definitely something about hens, but I didn’t grasp exactly what it was all about, to be honest with you,’ he says.

‘Well done,’ I remark dryly, sinking into the chair beside him, can’t face saying any more than that.

He chuckles, turns around and casts a glance in my direction.

‘That’s what happens when you forget your phone. You look tired,’ he says, a comment I take as an acknowledgement.

I am tired. So tired that every conversation, every gesture, every thought is an exertion.

‘Well, it’s Friday,’ Aslak says, as if to wrap up my thoughts, he smiles and pats my thigh. ‘Viljar wants tacos, but don’t blame me, all this stuff about everyone having tacos on a Friday night must be something he’s picked up at preschool. Do you know if Mia’s coming?’

Mia is with her father, and clearly not planning on joining us. Aslak looks so hopeful that I can’t face breaking it to him that she hasn’t been in touch for several days now.

‘Aren’t you going to get changed?’ I ask him instead, nodding at his work trousers. ‘Given that it’s Friday, and all that?’

I put off ringing Mum, head on up to see Viljar, who is sitting inside the little tepee in his room with his iPad resting in his lap.

‘Hi there, buddy,’ I say, sticking my head inside the tepee and kissing his cheek, my lips brush against salty, damp crumbs around his mouth, I realise his face and hands are bright orange. ‘Have you been snacking on cheese puffs before dinner?’ I ask loudly.

Viljar nods, his gaze still fixed on the screen, Peppa Pig. Aslak has no doubt given him the whole bag, some form of compensation, I think, if not, then it’s intended as some sort of dig, it can’t be anything else, but I’ve stopped trying to get my head around whatever it is he’s trying to achieve. I suspect that he doesn’t know anymore, either. I tease the bag from Viljar’s clutches, fortunately without objection.

‘Just one more episode,’ I say as Peppa and the rest of her family break out in the same absurd laughter that concludes each episode, family morale always perfectly intact, and Viljar casually, competently scrolls down the list of episodes.

I take a shower, wash my hair twice, lather myself in antibacterial soap I brought home from the office, scrub my body, under my nails, can’t get clean enough, there’s still bacteria on my skin and in my hair from all those patients with their rasping coughs, open sores, itchy crotches and overburdened souls. Some days it is as if their problems consume me, I can’t get a foothold, they just take what they want and leave. Days like that leave me powerless to argue, I dole out sick leave and prescriptions, refer people for MRIs and CT scans, send them to cardiac experts, all as my self-confidence plummets and my anxiety soars.

When I come back downstairs, I see that Aslak has fallen asleep on the sofa, I suppress the urge to wake him, to shout that if anyone should be sleeping on the sofa it’s surely me, but I leave him be, I don’t have the heart to complain or to start an argument when I haven’t the ability to say what I really want or feel. An argument that will reveal, above all else, the fact that I don’t really know what I want or feel. He’s lying with his arms crossed behind his head, I notice that he’s wearing his gold chain again, the one he received as a confirmation gift, the same one he stopped wearing when we moved to Oslo.

The carrier bags on the kitchen countertop are packed full, milk and sour cream and mince, the cartons and packets are wet with condensation. I wonder how early Aslak actually left work, how long he’s been lying on the sofa while Viljar has screen time in his room, a concept that Aslak refuses to acknowledge. He makes his way into the kitchen as I’m browning the mince, stands behind me and wraps his arms around me, kisses the nape of my neck. It’s a rare occurrence, I turn around and lean against him for a moment, sniff at his left armpit. I miss the smell of him when he used to get home after a day of lugging around and slotting together enormous planks of wood, the smell that conveyed strength and a primitive sense of security. He established himself as a furniture maker when we moved to Oslo and only ever smells faintly of wood oil and detergent these days.

I was the one who wanted to leave, I was the one who wanted to come here, I was the one who wanted this life.

He holds me for a while, tightens his grip before sighing and letting go, starts setting the table. I try calling Mia for a second time, silently pray that she’ll pick up the phone, can’t go making many more unanswered calls to her phone without her reading something into it, two missed calls could still just mean that I want to talk to her. I used to attempt to get through to people over and over again until I got hold of them, it took me a while to grasp the idea that doing so could be considered invasive or alarming, perhaps I didn’t really grasp it properly until the day Mia lost her temper with me. If I don’t pick up the phone, surely you realise that I’m busy, nobody rings five times in a row unless it’s some sort of emergency, she said, why the hell do you always have to be so intense?

She doesn’t pick up, of course, and I can picture her, sitting in Jens and Zadie’s kitchen, relaxed, smiling, the three of them making dinner together, the conversation flowing, all in English of course, for Zadie, something Mia thinks is a great learning opportunity, particularly useful since she’s planning on moving to London to study next year. I resist the temptation to leave her an irate voicemail, bemoaning the deep injustice around the fact that Jens, finally a fully-functioning adult at the age of forty-five, should find an obliging daughter, primed and waiting for him after all the years of hard work and love that Aslak and I have invested in her – particularly after the last few hellish years, which have featured endless rounds of upset and confrontation, arguments that have left me dumbfounded at what the unfamiliar individual before me is capable of thinking and bellowing. Where does this come from? I’ve wondered, it bears no resemblance to my own darkness, my own sense of rage, it bears no resemblance to me at all. Mia has been so controlled, so precise, at times so cunning and cold during confrontations, that on occasion, in the wake of our arguments, I’ve had to look at pictures of her as a young girl to remind myself that I still love her. This is all Jens, I’ve tried telling myself and Aslak several times, this is his doing, his genes, his absence.

But it bears no resemblance to Jens, either. He’s chronically evasive, incapable of making a single decision, of standing for anything other than his own impulses. I met him when I was nineteen, when he turned up in the village as a junior doctor – attractive only due to the fact that he was an outsider, that he offered something different, something new, an alternative to everything small and spent and cramped. And attractive because he had the ability to drown things out; he was excessive, transparent. I think you’ve been waiting for me, Sigrid, he remarked to me over his fourth beer on the night I met him. It was only later that it occurred to me that he was probably high on all sorts of opiates at the time, but it hadn’t mattered, there was no fight left in me, I was snared, trapped. After his foundation years ended he stuck around – because of me, I thought, because we’d settled on something without ever making it explicit, a life and a future together. I didn’t realise how aimless he was, how flighty – didn’t realise what I’ve since repeated to myself hundreds of times: that he was fragile, dependent, damaged, that he needed picking up, craved constant recognition or admiration or intoxication simply to keep himself afloat. Without the slightest hint of embarrassment, he would tell me about glowing praise from adoring patients, or commend his own skills and attributes in such an explicit manner that I misinterpreted it as an expression of sheer self-confidence and a statement of truth. It was a new experience for me, to find myself so wholly absorbed by another person in such a way, never able to get enough or be close enough. A yearning for him could flare up within me at any given moment, I could find myself pining for him, for more of him, even at times when we couldn’t possibly be any closer, when there wasn’t a millimetre of space between our bodies.

When I was five months pregnant with Mia, a complaint was made against him. A colleague discovered that he had issued a huge number of prescriptions for addictive medication, and in the space of just a few days, Jens decided that he needed a change of scenery. I’ve never told anyone that the person who drove him to the airport to travel to Bangladesh with an aid organisation was me, pregnant, furious and infatuated.

Mia calls me back after we’ve finished our tacos, after I’ve sung Viljar’s obligatory lullabies. Aslak and I are watching a film, each sitting on our own sofa. It’s so long since I last objected to spending our weekends in front of the television. At the very beginning of our relationship, more or less without thinking I tried to pressure Aslak into following the same routines that Jens and I had followed when we had been together; I can’t recall us spending a single evening watching television in all the years we spent together, I only recall conversations, sex, sorrow, arguments and reconciliation, all played out in an all-consuming vicious circle. We must have had more settled days, but I remember us as if in constant motion. Aslak’s sense of calm and stillness forces different shapes to emerge, different patterns, another life altogether. And had Jens not moved back to Oslo a year ago and invaded my life, invaded Mia’s, I wouldn’t be spending yet another evening impatiently comparing him to Aslak.

‘Hi, love,’ I say as I answer the phone, keeping my tone bright and breezy.

‘Hi, you called me?’ Mia says.

‘Yes, it’d just be nice to know if we should include you in our plans for dinner or not,’ I reply.

I sit there on the sofa, pulling at a loose thread along the seam of one of the cushions, where Aslak’s work trousers have chafed against the fabric every day after work without fail. He pauses the film.

‘I know, but if you don’t hear from me, then surely you realise I’m not coming,’ she says, and I try to listen out for Jens in the background, sounds, conversations, something to indicate what they’re up to, I hope they’re watching TV.

‘It’d be nice to hear either way,’ I say. ‘I hardly see you these days.’

This is close to crossing a line I promised myself I’d never cross with my children; I promised myself I’d never make them feel guilty, never leave them with the feeling that they owe me anything.

‘You saw me two days ago, Mum,’ Mia says, sounding more resigned than plagued by a guilty conscience.

‘But will you be staying there all weekend?’ I ask.

‘I don’t know, Dad and Zadie might be going out somewhere tomorrow night, so I think I’ll come back home if they do,’ she says, and the fact that she still refers to Aslak and me as home trumps both the fact that she’s started calling Jens ‘Dad’ and the desire to ask where he and Zadie might be going.

‘That’ll be nice. We’ll see you tomorrow, then,’ I reply, and out of the corner of my eye I see Aslak straightening up.

‘Sure, maybe. Grandma rang me a while ago, by the way, but I didn’t get to my phone in time, and now she’s not picking up when I try to call her back.’

‘She’s called us too, but it’s nothing urgent, Dad says it was just something or other about the hens,’ I tell her.

Aslak shuffles around on the sofa. There’s a brief pause.

‘OK, so, I’ll see you tomorrow or Sunday, then,’ Mia says. ‘Bye.’

‘OK, bye then,’ I reply.

Aslak looks at me as I hang up.

‘I’m sure she’ll be back tomorrow,’ I tell him, trying to smile, in that moment remembering Mia as a baby, lying on Aslak’s chest, the way he would gently blow on her head to help settle her.

It’s not unusual for Mum to call Mia, they often chat, probably more often than I speak to either of them on the phone. But there’s something about the timing, or perhaps it’s just me. Perhaps I’m always on my guard when Mum calls, and perhaps the relief that it’s never anything serious erases my memory of the anxiety I feel at receiving each call. Either way, it’s unlikely that Mum would have called to talk to me about the hens. I try calling her back once we’re in bed, but she doesn’t pick up. I check Facebook before bed, as I often do, to see how long it is since she, Mia and Magnus were last online. Mum was active nineteen minutes ago, I relax my shoulders. I register the fact that it’s also nineteen minutes since Jens last logged in.

I lie there and listen to Aslak breathing and the distant alarm in the city that I’ve never become accustomed to, it still disturbs me, even though I object when Aslak complains and says it’s impossible to sleep with the windows open in the summertime. Rubbish, this is one of Oslo’s quietest neighbourhoods, I told him during one of our first summers here, pushing open the window that looks onto the garden, you won’t find anywhere quieter than this if you want to live in the city, I continued. I’m not the one who wants to live here, he replied, closing the window.

I was the one who wanted to move to Oslo when I was done with my foundation training, when I was done with my studies and everything that had gone before them, done with village life, done with my feelings for Jens, done with Dad, done with Mum’s invasive loneliness. Aslak and Mia had to adapt to my needs, as he put it years later, not sounding angry or accusatory, more as if he were simply acknowledging the fact. I can’t carry an eternal debt of gratitude to you, I shouted at the time, not that he’s ever asked for gratitude, not once. But over the past year I’ve felt his need for some sort of assurance on a daily basis, payback in the form of some kind of commitment that I can never leave him. In the worst moments, my jealousy of Mia – her rebellion and freedom, the way she’s pulling away from Aslak – leaves me livid, and in that same instant, guiltily I grieve.

Mia has landed a job with a production company while she takes extra study credits, earning her own money for the first time in her life – the momentous discovery of economic freedom has propelled her need for independence. She arrives on Sunday morning, the previous day’s make-up smudged beneath her eyes, wearing a pair of jogging bottoms she’s borrowed from someone or other, too unflattering and far too baggy to belong to one of her female friends. She takes a seat at the kitchen table and helps herself to the bacon I’ve made for Viljar and Aslak. It takes all my strength not to tell her that I wasn’t counting on her being here for breakfast.

It must be nice having a grown-up daughter when you’re still so young yourself, you must be like friends, my own friends have said to me on more than one occasion. I’ve agreed with them, definitely nice, really nice to be a young mother to a daughter Mia’s age, yes, it is a bit like being friends, definitely. But I don’t want to be Mia’s friend in any way, shape or form. I don’t need to know where she spent last night, for example, not as long as she seems happy in herself. Mia, for her part, is still working out where the line is, occasionally she shares uncomfortably intimate details with me about her newly discovered and constantly expanding adulthood, while other weeks she’s silent and stand-offish with me. I want her to be able to tell me anything, I thought to myself when she was a child, that’s the sort of mother I want to be, and to remain, but in practice a line has appeared when it comes to Mia.

She looks happy, she looks like Jens, like him and him alone, as she fortunately laughs at one of Aslak’s many jokes. He’s trying too hard; I hope he’s able to strike a balance. I’ve witnessed numerous situations over the past few months, Aslak so happy and hyped up at any interaction between them, the fleeting moments of attention that Mia has graced him with, that he crosses a line only Mia and I can see, and then she unexpectedly utters some condescending comment, in the worst case involving Jens, as if it were coincidental.

Throughout her upbringing, Aslak has been the one to have meaningful conversations with her about Jens, and to be asked the most questions about him. You can’t say things like that, Aslak told me when Mia was six years old and wanted to include Jens in a picture of the three of us. She wondered what colour his hair was, I shrugged, said she could decide for herself. She was confused, of course, looked to Aslak. He’s got the same colour hair as you, he said. And the same colour eyes, he added hastily, without looking at me. She doesn’t need to know every little thing about him, I remarked later. She’s going to find out what she wants to know about him sooner or later, and I don’t want to be the one standing in the way of that, Aslak replied. His approach worked well until Jens moved to Oslo, until he came and cast Aslak and me in a different light, gave her something to compare us against.

The change is vague and irrefutable, I can’t find the words to articulate it, but neither do I dare pushing her further towards Jens, and both Aslak and I find ourselves unwillingly tiptoeing around her. It drives me mad, a fire rages within me, fuelled by a thousand comments and bellowed requests for her to turn her music down, to clean the bathroom as we agreed she would, to let us know if she’s coming home for dinner, not to throw coloured socks in with a white wash, not to forgive him, not to idolise him, not to disappear in him.

The past year has offered an uncomfortable taste of what life will be like when she moves out, I’ve felt myself struggling to breathe whenever I think about it – that she should be so far from me, and that I’ll be left to discover what Aslak and I are without her.

‘Did you manage to get through to Grandma?’ Mia asks as Aslak and I clear the table, she’s sitting on the bench with her legs tucked up beneath her.

‘No, I’ll call her later, but it’s nothing to worry about,’ I say.

‘Sure,’ Mia replies, ‘but I’m the sort of person who can’t help but worry.’

‘Oh, you are, are you?’ I reply, chuckling.

‘Oh, whatever,’ Mia replies, ‘you know what I mean.’

We’ve had this conversation many times before, I can’t help but remark on the need that she and her entire generation has to assert their own characteristics and personality traits. I’m a very empathetic person, a young girl who turned up in my office with a broken arm said to me once. I nodded as I looked at her arm, unaware of the context. Hmm, yes, is that hard for you, I replied, unsure. Not really, she replied breezily, things just hit me hard, if you know what I mean. I see, I replied, sending her off for an x-ray.

There’s something uncomfortable about being told what I should think about you, I’ve tried explaining to Mia. It fell on deaf ears. It’s more uncomfortable having someone see you the wrong way, she replied with a shrug, and perhaps she’s right.

Monday arrives with such a normalising force that I almost burst into tears on the train to Ellingsrud. The autumn darkness unites us passengers in a fellowship that I never feel on bright summer mornings, a sociable silence, perhaps a sense of mutual sympathy, an acknowledgement that we are among those who have been roused from their slumber at six o’clock in the morning to make it to work on time, in spite of the bleak November darkness and biting cold, no sign of snow. I am part of this fellowship, my shoulders pulled up to my ears as I blow into my hands, but there’s no month that I like more. No events, no annual celebrations, no emergencies, just the uninterrupted and tranquil darkness that eats away at the days in ever greater chunks.

The forty-minute commute to work and back has become the highlight of my day, a comfortable intermediate moment when I’m able to escape demanding patients and equally demanding relatives. As I step off the train, I try to call Mum for the third time, but get no reply, and for the first time since Friday I allow myself my usual worry for her, a feeling that is of such a constant and fixed size within me that it could be an aching body part in its own right, occasionally tamed, but ever present.

I spend a disproportionately long time seeing my first patients, as usual, spend far too much time with Ingrid. She’s ninety years old, and always carries a bag of boiled sweets, which she hands out to patients in the waiting room and staff on the front desk; she always strokes my cheek before she leaves, like some sort of universal grandmother figure. Her presence is so comforting and mild that I just want to keep her here with me, to suppress any thoughts of the day to come. Afterwards I’m struck with guilt on behalf of my next patients, guilt at having shown favouritism, and I spend much longer than necessary carrying out a gynaecological examination and signing off on a driver’s licence.

Just as I’m about to fetch Frida, who I know has already been sitting in the waiting room for an hour and a half, as she always does, Mum finally calls. Just before I manage to pick it up, Frida opens the door to my office. I reject the call.

‘Frida, you need to wait for me to come and get you. We’ve talked about this, haven’t we?’ I reply, trying to take a pedagogical approach without coming across as patronising, an impossible balance, particularly when Frida behaves like an impatient child.

‘But my appointment was at ten past, and your last patient left ages ago,’ she replies.

‘Go back out to the waiting room and wait to be called, please,’ I say, but Frida doesn’t believe that I’m being serious, she hovers in the doorway, uncertain. ‘I mean it,’ I tell her, turning to face my computer screen, swallowing.

‘I think I’m about to have the baby,’ she says.

‘You’re not,’ I tell her, still facing the screen, clenching my teeth until she finally closes the door.

I sit there for a few minutes and stare at her medical records without reading them, then make for the waiting room and call her back in. She’s already crying before she reaches my office, but I’ve grown used to that, her tears no longer knock me off balance, and I know that if I give her so much as a glimpse of hope or care beyond the professional boundaries, she’ll eat me alive, skin, hair, the lot.

I gave her a hug on one of the first occasions that I met her, didn’t know how to handle her depression and fear – and her expression intimated her belief that, once again, even after years knocking around a system that couldn’t accommodate her, she’d found someone who could help her. I’m going to help you, I thought at the time, still in the belief that I could. There are still days when I think I can, days that I believe the fact I’m here is help enough, someone stable she can talk to, with clear boundaries between us established over time.

It was difficult to like her the first time she turned up in my office. She was clingy and full of complaints, headstrong, with a medical record that she knew by heart, an endless list of hospital admissions, medication, social-security measures, a patchy record of attending psychiatric appointments, and an unreasonable number of GPs she had worked her way through. She’s been my patient for seven years now.

‘So, how are things?’ I ask once she’s taken a seat, passing her a box of tissues, as usual.

‘I think I’m about to have the baby,’ she says again. ‘Please,’ she continues.

She hiccups as she leans over her knees, her stomach pushing against her thighs, clasps her hands behind her head, rocking back and forth.

‘You’re not going to have the baby just yet, you’re only twenty-four weeks pregnant,’ I tell her. ‘But we’re past the halfway mark now, Frida, you can do this.’

I curse myself at my use of the word we, still make fundamental mistakes in my eagerness to help, to give her a sense of solidarity, when the most important thing is that she knows above all else that she’s alone in this, nobody is going to come and save her. Nobody apart from me, that is, and the thought sends me into a panic, the idea that I’m all she’s got.

‘I can’t do it, I want it gone,’ she shouts at the floor. ‘It’s eating away at me.’

A terrifying number of her thoughts remind me of those I had when I was pregnant with Mia, I remember how fear and loneliness manifested itself in absurd feelings and notions of being consumed. In Frida’s medical records, I’ve written that her thoughts are a sign of illness, that she’s imbalanced, on the verge of psychosis.

‘Nothing’s eating away at you, there’s a lovely, healthy baby growing inside you,’ I tell her, feeling that I’m choosing all the wrong words, the thing growing inside her is the very thing that it’s impossible for her to relate to, I remember that, but I don’t have any reserve energy to spend on finding the right way to approach her today, I’m already running over half an hour late after seeing only three patients. ‘Shall we take your blood pressure, then we’ll measure your bump after that?’

Frida gives in, straightens herself up, rolls up her sleeves. Her slender lower arms are covered in criss-crossing white scars. I didn’t mention them the first time I saw them, I remember her anticipation as I rolled up her sleeve, and her subsequent disappointment at my lack of reaction. The memory pains me, I could have offered her that satisfaction, I’ve thought to myself since, after getting to know her, growing fond of her.

Often I see myself when I look at her, recognise myself in her, she’s living out so many of my own inclinations, the things I need to control, to keep in check. I can’t get enough of seeing how she pushes the limits of every chart, boundless in her approach to the world around her.

I stand at the kitchen worktop in the break room and eat a yoghurt for my lunch, feeling like time passes more quickly if I don’t sit down, and the smartwatch Aslak gave me for Christmas has already reminded me umpteen times that I need to get moving. The two other doctors I share a practice with are sitting with their phones in their hands as they eat, in spite of the fact that we decided long ago that lunch would be device-free time, a ‘tranquil oasis’ in our day, a half-hour period during which we could chat and keep one another up-to-date on things, share our experiences and any potential frustrations.

I take the rest of my yoghurt into my office, call Mum. She picks up straight away.

‘Finally,’ she says.

‘Hi to you too,’ I say.

‘I’ve been trying to get hold of you all weekend,’ she says.

‘Hardly, you’ve tried calling me once. If anything, the opposite is true, I’ve tried calling you back several times now,’ I reply.

She falls silent for a few seconds, I can hear the sound of the kettle in the background, picture the kitchen at home, Mum in her yellow cardigan, her green teacup.

‘None of you picked up when I called, in any case,’ she says. ‘I was starting to think there might be some conspiracy in the works.’

She chuckles briefly.

‘I wouldn’t worry about that, I haven’t heard from Magnus in weeks,’ I reply. ‘Was there something in particular you wanted to discuss?’

‘No, it was really just about the hens, I told Aslak when I spoke to him that I wanted to speak to you all before I butchered them, Viljar is so fond of them, and…’

Mum has had chickens ever since Dad became disabled and they’d had to slaughter the cattle and sheep, she insisted that a farm needed animals and promptly acquired twelve birds. I remember seeing headless chickens running around the yard at home after Mum had beheaded the first brood. She had invited her natural-sciences class along to give them a chance to learn about the circle of life, the fact that the chicken breasts they had for dinner didn’t simply materialise in the supermarket freezer aisle. They don’t come from tough, old birds like those either, Mum, Magnus said to her, but Mum carried on bringing students to watch the birds being butchered right up until a few parents complained to the headteacher on behalf of their traumatised children.

Viljar has, as far as I know, never had any kind of special fondness for Mum’s chickens, quite the opposite, in fact, he’s shown clear and somewhat troubling signs of a general phobia of birds, the root cause of which I haven’t bothered to investigate. To claim that she’s thinking of Viljar is just another way of making me feel guilty.

‘It’s nice of you to think of Viljar,’ I remark. ‘But obviously you have to do what you think is best when it comes to the chickens, Mum.’

‘Well, it’s too late now in any case,’ she says. ‘I slaughtered them on Thursday.’

3

‘But if you already slaughtered them on Thursday, then I’m not sure I understand quite why it was so important to get a hold of us on Friday,’ Sigrid says.

I fill the tub on the kitchen countertop with the boiling water from the kettle, don’t know how to carry on the conversation, shouldn’t have chosen such a roundabout approach involving the hens, should have gone straight to the heart of the matter, as I’d intended to on Friday, but all weekend I’ve imagined Sigrid and the impossible prospect of having to bring more of me and my issues to the fore.

‘No, I meant Friday, I slaughtered them on Friday,’ I tell her. ‘But that’s enough about all that. How are things with all of you?’

‘Good thanks, but I’m at work just now, so if it’s not urgent than perhaps we can talk this afternoon instead,’ she suggests, she sounds hesitant, no doubt keen to avoid committing herself to yet another conversation.

I always think something might change when I speak to her, I don’t realise it until the call is over, I’m always left with a sense that something has been left unsaid. I often feel frustrated for days following our conversations, at the reproach in her tone and her pauses, the brief moment of silence she leaves before she answers, as if to give me time to say more.

‘Of course,’ I tell her. ‘Of course we can speak this afternoon.’

I carry the tub outside, only got as far as plucking the birds roughly and removing the innards on Friday before I had to concede defeat and place the half-prepared carcasses in the freezer. I hauled my body onto the sofa after that, where I lay for hours, exhausted. The chickens are piled up inside the freezer out in the barn, which is already full of game that I haven’t managed to bring myself to eat, but which I found myself equally unable to dispose of after giving in and placing Gustav in a nursing home.

I can’t imagine I’ll eat any of the chickens either, but it feels significant, turning them into food in this way, no detours or unnecessary carbon emissions. I fetch one of the headless carcasses from the freezer, try to avoid reading any of the labels on the rest of the meat, Gustav’s sloping handwriting, Elk Tenderloin 2009, the last year he’d joined the hunt, when the others had practically had to carry him out to his post. They had honoured him with tenderloin steaks from one of the elks they’d shot, something that left him feeling more embarrassed than having insisted on joining the hunt in the first place. He was wheelchair-bound by the following year.

I give the frozen chickens a better clean, my fingers in their yellow rubber gloves growing stiff with the cold, but I refuse to give in, need to finish the job before Sigrid calls me back; I am struck with a sense that everything has to be in order before I tell her, I realise that I probably ought to go and see Gustav first too, get all of my tasks out of the way.

Gustav is sitting by the window when I arrive, as usual, looking down on the farm and on me. His hair is grey, almost white, and still thick in contrast to his slender frame. I am occasionally surprised when I see him as he truly is; the fact that he no longer looks the way he does in my mind’s eye, my memories.

‘Hello, you,’ I say, leaning over and giving him a hug. ‘Didn’t they shave you today, either?’ I ask, stroking his stubbly cheek.

He lifts his gaze and looks at me, starts to laugh, he still has a surprisingly good set of teeth, strong and white. He’s always taken care of his teeth, he used to say that you could tell a lot about a person from how well they looked after their teeth, and he followed a strict routine when it came to brushing and flossing every morning and evening. Even after he could no longer remember how to turn on the shower, he carried on cleaning his own teeth.

I release the brake on his wheelchair and wheel him to his room, can’t bear to sit there being gawked at by the carers or other patients. I think you’re supposed to call them residents, Mum, Magnus said when he was last here. He was sitting at the table in the corner with Sigrid and me, we talked around Gustav, as always ends up being the case when they come, we’ve never been able to find a method of communication that includes him. I can’t talk to Gustav the way I do when it’s just the two of us, and I don’t imagine Sigrid and Magnus can, or want to, either. Why should I call them residents? I asked. The only reason they live here is because they’re ill, and ill people receiving treatment are, by their very nature, patients, I continued. Sigrid nodded, but I’ve heard her refer to her own patients as users or something along those lines on numerous occasions, something intended to confer a more equal status upon them. I’ve confronted her about it, why on earth would any patient want to share an equal status with their doctor, that would certainly leave me feeling deeply concerned, I told her the last time we spoke, you’ve gone there seeking help, that’s the whole point. That requires some sort of hierarchy. Sigrid said nothing, just flashed Magnus the same knowing look she so often does, self-pitying, almost pleading, seeking reassurance, as if I had attacked or criticised or offended her during the conversation, during every conversation.

Either way, I feel less confident about my own arguments now. Referring to myself as a patient does, on the one hand, offer a certain passivity, a safe denial of liability, but on the other hand it is a role I cannot completely identify with, it’s perfectly possible that I might end up feeling more like a user, some sort of participant with a greater degree of control.

The other residents are much older than Gustav on the whole, and on numerous occasions I’ve felt that the situation must be accelerating his cerebral atrophy, finding himself surrounded by stooped, ailing individuals. Whenever I make my way across the car park towards the entrance to Gustav’s final fixed abode, I allow all my thoughts about how awful it must be for him to live here to wash over me.

Today things feel slightly more straightforward, I even manage to make a little small talk with Gustav on our way to his room, smile at the carer I usually do my best to avoid because I can’t bear the disapproval I see in his expression. Once Gustav and I are alone in his room, my shoulders relax. I take off my cardigan, park his chair by the headboard of his bed then lie down there, my head on his pillow, breathing in his scent. I inhale deeply, exhale slowly, reach out a hand and stroke his face once again, take his hand and squeeze it in mine, unable to hold back my tears. For the first time since Thursday, I cry. I suddenly feel so sorry for Gustav, it’s unbearable to think how awful it must be for him.

‘Don’t mind me, I’ve been dealing with the chickens all day,’ I remark as I look up at him, try to squeeze out a chuckle as I wipe away my tears with the sleeve of his jumper. ‘I know you’ve never understood it, but you can become fond of them.’

He pulls his hand back, but there’s nothing aggressive about the gesture. I take it once again. Carefully place it on my chest, over my T-shirt, my own hand on top of his. I lay my head back and relax, feel myself beginning to nod off until I suddenly feel him squeezing my breast. I turn to face him, smile. I shuffle upwards in the bed, resist the temptation to move his hand to other parts of my body, still recall his wild fury when I sat on his lap one Sunday a few years ago. And his reactions on the countless occasions that I’ve touched him in ways that no longer have any place in our life. Sometimes I think that my touch is to blame, my body against his, that it awakens memories, a desire for which he has no outlet – or perhaps that the damaged nerve endings in his brain confuse desire and anger. But more often than not it is the way that he pushes me away, squirming free, that serves as a reminder of just how much he blames me, perhaps even loathes me, for giving up on him and moving him in here. A long time has passed since I last dared expose myself to such rejection, but today I find that I can’t help myself, I squeeze his hand where it rests on my breast, need to feel his presence, which is, in many ways, much less complicated now than it was when he was in good health.

I consider rehearsing my conversation with Sigrid, but decide against it. Even though Sigrid and various other doctors have stressed the fact that he no longer remembers any of us, occasionally I catch a glimpse of something within him, a gesture or expression that doesn’t fit in the context of his illness – and since no one can know for certain exactly what he picks up on and what passes him by, I’ve decided to proceed on the basis that he understands more than we think.

‘I had a long chat with Sigrid a little while ago,’ I tell him, getting up. ‘She wanted me to say hello and to tell you that she misses you,’ I continue as I roll his chair into the bathroom, parking him in front of the mirror and finding his razor.