One Lucky Devil E-Book

2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Shadowpaw Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Born in Scotland, Sampson J. Goodfellow emigrated to Toronto as a child. Like many young Canadian men, he returned to Europe to serve his new country in the First World War, first as a truck driver, then as a navigator on Handley Page bombers.

Over a span of just six years, Sam witnessed Canada’s deadliest-ever tornado, sparred with world-champion lightweight boxers, survived seasickness and submarines, came under artillery fire at Vimy Ridge, was bombed by German aircraft while unloading shells at an ammunition dump at Passchendaele, joined the Royal Flying Corps, was top of his class in observer school, became a navigator, faced a court-martial for allegedly shooting up the King’s horse-breeding stables, survived being shot down by anti-aircraft fire, was captured at bayonet point and interrogated, became a prisoner of war in Germany...and, in the midst of all that, got engaged.

When Sam was listed as missing, the family of his fiancée went to a fortuneteller for news of his fate. “You couldn’t kill that devil,” she told them. “He is alive and trying to escape.” She was right.

With a sharp eye, a keen mind, a strong body, and an acerbic tongue, Sam survived, as one RAF officer put it when he returned to England after the Armistice, “enough to be dead several times.”

“You have been through hell,” a military doctor told him, “and you have been very lucky as a soldier and airman.”

Sampson J. Goodfellow really was “one lucky devil.” This is his story, in his own words.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 175

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

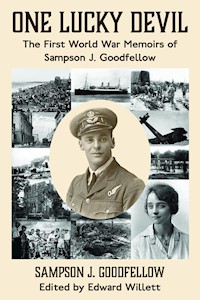

One Lucky Devil

The First World War Memoirs of Sampson J. Goodfellow

Sampson J. Goodfellow

Edited byEdward Willett

ONE LUCKY DEVIL:

The First World War Memoirs

of Sampson J. Goodfellow

Text copyright 2018

Estate of Sampson J. Goodfellow

All rights reserved

All images believed to be in public domain.

Cover design by Edward Willett

ISBN 978-1-9993827-6-6

Kindle ISBN 978-1-9993827-7-3

Epub ISBN 978-1-9993827-8-0

Order from:

SHADOWPAW PRESS

303 - 2333 Scarth Street

Regina, Saskatchewan

Canada S4P 2J8

www.shadowpawpress.com

Contents

Foreword

1. A Scottish Childhood

2. A New Country

3. A Machinist in Regina

4. Education and Enlistment

5. Farewell to Family

6. Not-so-Jolly Old England

7. Le Havre to the Somme

8. A Bad Winter

9. Vimy Ridge

10. Under Fire at Passchendaele

11. Into the Flying Corps

12. An Advanced Course

13. Bad Trouble in Bath

14. A Non-Military Engagement

15. Top of the Class

16. Court-Martial

17. “The Slaughter was Terrible”

18. “Good-bye, They Have Got You This Time!”

19. “I Want Your Squadron!”

20. Prisoner of War

21. Armistice

22. “A Dirty-Looking Devil”

23. Wedding Bells

24. A Return to Childhood Haunts

25. The Curious Case of the Zoological Gardens Steam Engine

26. “I Wish We Had More of Your Caliber”

27. The Canadians Run Amok

28. Officer in Charge

29. A New Life Begins

About Sam and Nancy Goodfellow

About the Editor

Foreword

I NEVER MET SAM GOODFELLOW. He died in 1979, when I was at university in Arkansas. After graduation I returned to my home town of Weyburn to work at the Weyburn Review, and almost ten years passed before I moved to Regina. But nine years after I arrived in the city, I married Margaret Anne Hodges, P.Eng., Sam’s granddaughter, and acquired a wonderful mother-in-law, Dr. Alice Goodfellow—Sam’s daughter.

Dr. Goodfellow, who passed away in 2013, lived in the house that Sam and Nancy bought in 1939. Now I live in that house, with Margaret Anne and our daughter, also named Alice. A lot of our furniture once belonged to Sam and Nancy, including a wonderful grand piano, and there are knick-knacks and oddments and keepsakes galore that date to their married life, and even before—for example, opera scores that Nancy brought from England. (Some of these formed the basis for a series of spots I did on CBC Saskatchewan’s Afternoon Edition radio program when Colin Grewar hosted it, called, “Things I Found in My Mother-in-Law’s House.”)

As a result, I rather felt I did know Sam, even before I discovered the memoirs he had written late in life, sometime in the 1970s. Typed up and bound in loose-leaf notebooks, they fascinated me from the beginning with their account of his childhood in Scotland, his early years in Toronto and Regina, and, especially, his service in the Great War.

Ten years ago, I posted these memoirs (at the time, largely unedited) online, on my website, www.edwardwillett.com. But with the arrival of 2018, and with it the centennial of the Armistice that ended the First World War, I decided it was time to act on an idea I’d had from the beginning: to properly edit and release in print form Sam’s personal account of his early life and experiences during the war.

Earlier this year I started my own publishing house, Shadowpaw Press, with the thought that this would be one of its earliest releases. And so, here it is: one man’s sharply observed account of his service in the war that ended one hundred years ago this November.

I have edited with a light hand, correcting grammar and spelling here and there and making an effort to ensure that place names and other proper nouns are correct (where there’s significant uncertainty, I’ve inserted an editor’s note). But by and large, these are Sam’s words, just as these are Sam’s experiences.

I hope you find them as fascinating and enlightening as I did, and that you will feel, as do I, that you’ve met someone you’ll remember all your life.

Edward Willett

Regina, Saskatchewan

October 2018

1

A Scottish Childhood

One day when I was twelve years old, I said to my mother, “What happened when I was around three or four years old?”

Mother looked at me. “What do you mean? What do you remember?”

“I really don’t know,” I said, “but something has bothered me for a long time. There seems to have been a great disturbance, a quarrel, a fight, or some misunderstanding. Please tell me what it was.”

After a moment, Mother said, “Very well, I’ll tell you. It’s only right that you should know. The incident you refer to was when your father wanted to go to the United States of America to start a new life. He felt that on account of conditions in Scotland, and with so many others emigrating to America, that it would be the best for you and your brother, and also me. The Americans were opening up their country—they were wanting people for agriculture and manufacturing and more. It was a new country, with greater opportunities for workers, and no class distinction. They wanted pioneers.”

But, Mother told me, she had a premonition that if my father went, she would never see him again, that he would either desert her or be killed—and she was correct: she was later informed he had been killed in a rail accident before he could save enough money to send for us. He had been buried in Philadelphia.

Mother said she was surprised I could remember the incident. “It must have made a great impression!”

Mother always seemed to be able to glimpse into the future. Perception or intuition, call it what you will, she always knew what was happening to any of her relatives, and was always correct. At my young age, it seemed very frightening.

Sometimes friends would come to our house to have their fortunes told with playing cards or have their tea leaves or palms read (a common practice at the time when people visited each other’s homes). It was lots of fun because I made jokes about it, but when the reading came true, I shivered.

My father had been the youngest boy of his family and was well and truly spoiled. He could not stand discipline or chastisement, and so he left his home town of Hanley, Staffordshire, and went to Edinburgh, Scotland, where a brother, Fred, was living. That didn’t suit him either, so he wandered all over Scotland for a while, before finally returning to Edinburgh.

By all accounts he was a handsome daredevil, always up to some prank with his chums. When his friends—ex-soldiers, sailors, and others—decided they were going to America, of course he wanted to go along—which he did.

As a result, Mother was left with two children, me and my little brother, Fred, two years my junior, to rear and educate. We lived in many different homes under poor conditions, and our health started to fail.

I remember falling sick and being rushed to the hospital with a childhood disease. I remember it not so much because I was sick (it wasn’t long before I was out), but because one day Mother brought me a banana. It was the first I had seen, and it tasted wonderful.

Another incident while living in Edinburgh that I remember well was the day we were taken to the sea-side resort of Portobello (remember the school-girl rhyme in The Pride of Miss Jean Brodie, “Edinburgh, Leith, Portobello, Musselburgh, and Dalkeith?”). Whoever took us did not know that children left alone have the habit of wandering, which Fred and I did.

Our wandering ended when we were picked up by the local policemen and taken to the police station. The police at the station had lots of fun with us. I can remember (as if it were yesterday) them buying us ice cream—or it may have been hokey pokey (penny a lump!). When Mother got in touch with the police, they hated to see us go because they were having so much fun amusing us.

Portobello Beach, ca. 1900 (City of Edinburgh Council).

I can also remember going to Holyrood Palace, which at that time was a soldiers’ barracks. The soldiers, too, would have lots of fun with us, and give us a penny.

Finally, Mother decided we had to leave Edinburgh. After she saw an advertisement in The Scotsman newspaper, we were taken to Langside Cottage, in the country outside of Dalkeith.

Langside Farm Cottage near Dalkeith (seen here in Google Street View). This may be the same cottage, or at least in the same location.

It was a lovely place. You came up a grade from Dalkeith, with a forest on the righthand side and farmers’ fields on the left. At the corner was a rise of ground where I used to lie, dreaming about what I would do when I grew up, my imagination running wild (although I never thought I would go to Canada, since I didn’t know there was such a place!).

On Saturday and Sunday, the poachers would come out with their hounds to chase the rabbits—provided the gamekeeper was not around. If the gamekeeper appeared, they would chain up their dogs, leaving the gamekeeper with no proof they were poaching—they just said they were exercising their dogs.

The land belonged to the Duke of Buccleuch, and the farmers were mostly tenant farmers. Behind one of the fields was a small pond where we kids used to swim in the nude.

I remember vividly one time when, while the older people had dinner in the cottage, Fred and I stayed in the yard and sat on a little bench. They gave us our meal, which was half an egg each.

Fred looked at it in disgust. “Half an egg!”

“You got the best of it,” I pointed out. “You got the bottom half, which is round and larger. I got the top, which is very pointed!”

Langside Cottage belonged to the Reid family. Mr. Reid was an official at a mine a few miles away. He and his wife had two sons, Tom and Jim, and a daughter, Alice, for whom they had built a special rose garden. They also had a vegetable garden. (The men of the family mostly kept to the horse yard, which was huge.)

Jim, the youngest child (and spoiled as a result), was a few years older than us. He was a card, always up to some mischief. He was done with lessons at the village school and did all the work around the cottage, looking after the horses and gardens, a big job.

Mother had arranged for us to live with the Reids while she returned to Edinburgh to work. She said she would come frequently to see us, which she did.

Sometimes Mother took us to Edinburgh to see Punch and Judy at Princes Street Gardens and to play on the lawns. One time, Mother took us to Leith, where we got on the boat and went under the Forth Bridge and as far as Rosyth. It must have been that trip, seeing the Forth Bridge, that made me decide to be an engineer: I wanted to build bridges and canals.

I was told that painting the bridge was a continuous process, that when they finished one end they started to paint again at the other. I could believe it, because it was such a huge structure.

The bridge over the Firth of Forth, ca. 1900 (Wikimedia Commons).

One Easter, Mother dyed eggs and took us to Arthur’s Seat. At the time it had a lovely pond and lawns. (When I visited Arthur’s seat during the First War, it was a terrible mess!)

When Mr. and Mrs. Reid went to Dalkeith or other nearby towns in their single-horse cart they would take Fred and me along and buy us treats: gingerbread cake, or a Lucky Bag (which contained a toy and miscellaneous candies), or a licorice strap, made of strips that we could peel apart and chew.

I remember one occasion when we were left at home under Jim’s authority. Jim said, “Let us make some potato stovies.” But we didn’t have any potatoes, and of course, we couldn’t use Mrs. Reid’s spuds, or we would get found out. (You know what frugal Scots are like!)

Jim said, “Get out your little cart and get some out of the farmer’s field next to the cottage.”

The Scottish farmers in this district rotated their crops. The potatoes in this field had been harvested and were stored in the field. This was done by digging a huge ditch a couple of feet deep in the ground, lining it with straw, and then piling in the potatoes below and above the ground and covering them with straw sheaves.

Fred and I went out and filled our barrow with the potatoes, then I got up on the straw potato hut to see if anyone was coming before we went on the road home. The road had a little bend, and who should be coming along but the policeman from the village where our school was.

As it happened, I was pulling the cart. Fred spread himself out over it so the policeman wouldn’t see the potatoes. We had a laugh with the policeman and then said goodbye when we pulled into the Reids’ yard. We thought we’d pulled the wool over his eyes, but no doubt the policeman knew what we were up to!

Then Jim told us the Reids had been told to help themselves whenever they wanted turnips or potatoes, because they did favours for the farmer, such as acting as caretakers. This came as a great relief. Fred and I had thought we would go to prison for life, but it turned out it was just Jim delighting in giving us a scare.

Jim made the stovies, and they tasted lovely. We cleaned up everything so Mr. and Mrs. Reid would not know, but they were suspicious anyway, because the three of us couldn’t eat our evening meal!

The Reids were great people. They understood the pranks of boys and closed their eyes to our little tricks. That being said, though, there was another time when Fred and I really did get into trouble.

We always went to a farm with a tin pitcher for the milk. When we came home from school, a walk of about three miles, sometimes we would have a drink out of the pitcher and put in water from the burn—but this time we drank too much and, of course, put in too much water.

Mrs. Reid remarked that the milk was getting too poor and looked at Fred and me; we looked guilty, and Mrs. Reid instantly knew what we had done. We were sent to bed without our supper. Jim sneaked in some food to us, but believe me, it was a lesson: we never took another drink of the milk.

In the morning, when we got up at seven to go to school, we would get a bowl of porridge, a slice of homemade bread, a glass of milk, and then away we went, meeting the farm children from the district as we walked the three and a half miles to our two-room school. In one room, a lady taught the juniors, while in the other, a man taught the higher grades.

For lunch, we’d have treacle on a slice of bread (we were given a penny each morning to pay for it) and a glass of water, and then away we’d go to play rounders or soccer (though, of course, in Scotland we called it football).

(Because I played rounders so much at school in Scotland, when I later became a junior baseball player in Toronto, I did not have to be told or taught the fundamentals of the game. They’re the same: hit the ball and run to get on base. Of course, baseball is more scientific.)

In the afternoon, when we got home to the cottage, we were given a bowl of porridge until the men came home.

During our stay at Langside Cottage, an uncle, Mr. Andrew Baillie, who had married Mother’s older sister and operated a steam laundry in the City of Toronto, visited his father in Edinburgh, and also visited my mother. He acquainted her with the opportunities in Canada for her two boys, and after giving it a great deal of thought (because she held a very good position), Mother finally decided to emigrate to Canada when my uncle returned home.

It was the summer of 1902. I was nine and a half and my brother was seven and a half. At school, I had progressed to the senior grades, while Fred was still in the lower grades.

Mother came to Langside Cottage to take us back to Edinburgh. The Reids were downhearted to see us leave but wished us good luck in our new country of Canada.

We reached Edinburgh on the night of May 31, 1902—the day the Boer forces surrendered to end the Second Boer War—and stayed at a private hotel on Princes Street, with a balcony where we could sit and see Princes Street Gardens and Edinburgh Castle. The fireworks display was beyond description, and the people on the street were jubilant, shouting and dancing. The lady who operated the hotel and her daughter were with us, and we had a wonderful night.

The next morning came too soon. We departed Auld Reekie for Glasgow, where we saw the large ocean-going ships in the River Clyde, one of which was to take us to our new country: Canada.

What I could not understand about Glasgow was how the street cars operated with an overhead wire, because our cars in Edinburgh moved by gripping an underground cable (the same system used by the famous cable cars in San Francisco).

Springburn Road, Glasgow, ca. 1900 (from an old postcard).

I stood on the street trying to understand how the cars could move with a little wheel on the end of a pole, until someone informed me about the magic of electricity.

We boarded our ocean liner and were soon on our way down the Clyde. It was “Auld Lang Syne,” at least for me.

2

A New Country

At the south end of Ireland we stopped to take on passengers from a ferry boat, then we were on our way across the Atlantic. It was a rough passage: several times the hatches were closed, preventing us from going on deck, and one time the angle of the deck was so acute my uncle’s leg went through the deck guard railing.

We saw whales spouting water in the air, and fish following us. As we approached the shores, swarms of gulls surrounded the boat, looking for food.

We finally reached the St. Lawrence River, and then Quebec, where the third-class passengers disembarked. It was peculiar to see how the native French Quebec people dressed, and hear the language they used. We could not understand them. I wondered if I would have to learn a new language.

We finally got on a train (with very hard seats) and travelled through a beautiful countryside, seeing some wonderful sights. I immediately fell in love with my new country.

Yonge Street, Toronto, during the celebrations marking the end of the Boer War, just days before the Goodfellow family arrived (photo by William James, via Wikimedia Commons).

At last, we reached Toronto, where we were met by the Baillies: my mother’s sister, Cecilia, four girls (Calia, Anna, Bella, and Alice), and a teenaged boy, William.

The transfer to a new country did not, at the beginning, work out very well, because it turned out that all my mother’s relatives wanted from her was unpaid labour.

Fred and I attended Ryerson School. We wore Scottish clothes, and because we were immigrants we didn’t get along with the teachers. As well, the children of our age and older would fight with us—if we could not outrun them, we had to stay and fight.

Fred, being younger, got a lot of beatings—I had to come to his aid many times, until we finally convinced them that we could hold our own, and better. (In fact, several times the fathers of some of the other children came to our house to complain about us giving their children black eyes and cut lips.)

As the weeks passed, it started getting cold. Mother asked for her pay and was told the keep for her and her two boys was the pay. “I work from seven in the morning until ten at night,” she protested. “The boys need winter underwear and heavy clothes and I need clothes, too.” It made no difference.

Finally, my aunt told my mother that her husband had paid our way to Canada.