Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

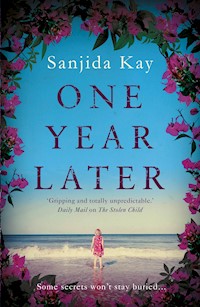

Since Amy's daughter, Ruby-May, died in a terrible accident, her family have been beset by grief. One year later, the family decide to go on holiday to mend their wounds. An idyllic island in Italy seems the perfect place for them to heal and repair their relationships with one another. But no sooner have they arrived than they discover nothing on this remote island is quite as it seems. And with the anniversary of the little girl's death looming, it becomes clear that at least one person in the family is hiding a shocking secret. As things start to go rapidly wrong, Amy begins to question whether everyone will make it home...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 403

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ONE YEAR LATER

Also by Sanjida Kay

Bone by BoneThe Stolen ChildMy Mother’s Secret

Published in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Sanjida Kay, 2019

The moral right of Sanjida Kay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Atlantic Books Ltd considers the quotes included within this text to be covered by the Fair Dealing definition under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and as subsequently amended. For more information, please contact Atlantic Books Ltd.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 255 5

Export trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 879 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 256 2

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To my family

–Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Ah me! how hard a thing it is to say

What was this forest savage, rough, and stern,

Which in the very thought renews the fear…

I did not die, and yet I lost life’s breath.

The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri

PROLOGUE

He stands on the edge of the cliff and stares at the drop below. It’s early, around 5 a.m., and he’s only had two hours’ sleep. He blinks, rubs his eyes. The wind, skimmed straight from the sea, is cold, and he can taste the salt on his tongue. There’s a pale-blue line where the ocean meets the sky: the first sign of the approaching dawn. He has a torch in his pocket, but it’s of little use, faced with the dark expanse of beach below him. He shifts slightly and feels the earth give way beneath one foot.

He doesn’t have long.

The tide is almost fully in, and the man who’d phoned him had said she was at one end of the beach. The caller was drunk; he said he was on his way home from the festival, although that in itself was suspicious, because no one lives at this end of the island, save for the Donati family and the people staying in the holiday house below their farm. The man was slurring his words – fear, combined with the alcohol, making him barely comprehensible. He didn’t say which end of the beach. Martelli had driven here as fast as he could, radioing for the ambulance from the car. He offers a silent prayer: that she is above the tideline, that he can find her in time, that she’s still alive.

The clouds shift; the line of light over the water turns to buttermilk, and he thinks he can see her. Could be rocks or flotsam. Or a body. If it is the English girl, she’s lying stretched out on the sand below the headland, where this spit of land joins il cavalluccio marino.

He clicks the torch on and starts down the cliff path. It’s treacherous in daylight, never mind at night: narrow, twisting and steep, stones breaking through the soil. He slips, thinks he’s going to lose his footing. He can’t see how far it is to the bottom. He slides, collapses back against the side of the cliff, grabbing handfuls of vegetation to stop himself from falling the rest of the way. Loose grit and pebbles slide from beneath his boots, and he can smell the sweet, sharp scent of thyme and wild marjoram where he’s crushed the plants in his fists. It’s momentarily comforting: his grandma puts them in her rigatoni campagnolo. But then his torch hits a rock on the shore and the bulb smashes. He’s in darkness, his breath ragged in his throat. He pushes himself half-upright and scrambles the rest of the way down. His ankle throbs where he’s grazed it. The paramedics are not going to be able to carry her up here on a stretcher, he thinks, and the tide is approaching so fast, he’s not sure if they’ll make it round the headland, either.

If she’s still alive.

He runs across the sand, through crisp, dried seaweed and a ragged line of plastic bottles, Coke cans scoured clean, baling twine and polystyrene chips. The tourists can’t reach this beach, so no one clears away the rubbish. She’s on her side, one arm flung out, her legs at a disjointed angle. Has she fallen from the cliff? The rocks surrounding her are sharp as needles, erupting through the sand like prehistoric teeth. The foam-tipped edge of a wave creeps across the toes of her right foot. She’s missing one sandal. Her white summer dress is rucked up, exposing her thighs, revealing part of one breast. He throws himself onto his knees next to her. Her dark hair is wet and covers her face, so he can’t see what she looks like – if she is the missing girl. But he can see the blood: an uneven pool staining the sand, spreading out from the back of her head.

Where the hell is the ambulance?

His radio crackles, but there’s no word from the paramedics. He gently touches her with the tips of his fingers, and she’s cold, so cold.

Mio Dio.

He’s never seen a dead body before and his stomach clenches into a tight fist. Briefly he brushes the crucifix hidden under his shirt and then slides his hand beneath her hair, feeling for a pulse.

PART I

JULY, BRISTOL

1

AMY

It’s as if the day has gone into reverse. Amy puts on lipstick and feels like she’s getting ready for work instead of a night out with her husband. There’s something hard and smooth in the pit of her stomach; it’s the shape of an avocado stone, but larger, heavier. She can’t remember the last time she and Matt went out. Before, probably. Most things happened before. She scrutinizes herself. She’s thirty-six, but she looks ten years older; there are hollows beneath her cheeks, and her face has concertinaed into those folds that athletes get when their body fat drops. She’s never been thin before. She always wanted to be slimmer, but now that she is, she hates it. Misery skinniness might look good in photos, but it’s unattractive in real life. Matt winces sometimes when they try and make love, as if he might break her or she’ll pierce him with a hipbone. She tries a smile. It’s what the self-help books say: Smile and then you’ll really start feeling happy! She covers the place where her dress gapes across her chest with a scarf and tucks the lipstick into the pocket of her handbag.

Nick should be here soon, she thinks. He’s late, but then he always is. She goes to check on the children. Theo is sitting up in bed, reading.

‘How fast can light travel?’ he asks, without looking up. Although he’s only eight years old, it feels as if he’s been obsessed with space his entire life.

‘Oh, I know this one! Seven times round the Earth in one second.’

The upbeat voice she tries to use with the children sounds fake and brittle, even to her.

‘How many stars are there in space?’

‘As many as the grains of sand in the sea.’

He rolls his eyes. ‘Wrong.’

‘Okay then. Seventy thousand million million million.’

‘Seventy sextillion, you mean,’ he says, but there’s a grudging note in his voice.

‘I’ve been revising.’ She gives him a kiss. ‘Night, love. You remember Uncle Nick will be looking after you?’ He nods. ‘Fifteen more minutes and then put your light out.’

She peeks into Lotte’s room. There are pink-and-purple unicorns spiralling across the ceiling from a night-light. Lotte, two years younger than Theo, has been in bed for longer and is already snoring softly. Amy touches her forehead with the back of her hand. She feels hot, so she pushes the bedcovers down a little and worries whether it was sensible to let her wear a long nightie. She switches the night-light off, remembering, as she always does, that it isn’t Lotte’s.

Ruby-May’s bedroom is opposite. Amy stands in the doorway. The room isn’t quite dark: the curtains are open slightly and a street light shines through. She can see the curve of Ruby-May’s new bed. Her youngest daughter was delighted that she didn’t have to sleep in a cot any more and she was now officially a big girl. Amy resists the urge to draw the curtains fully closed, but she can’t help going in and sitting at the end of the bed. It’s so low down, her knees are almost level with her chin. She picks up Ruby-May’s doll, Pearl, and sets it on her lap. Its hard, plastic hands poke into her ribs. On the shelf opposite is Ruby-May’s Beatrix Potter collection; it was Amy’s, when she was little. Lined up in front of the books is a set of Beanie Boos, with large eyes that glitter in the muted light. There’s a thin bottle of gin tucked behind The Tale of Peter Rabbit, but she resists that urge too. She listens for her daughter’s breathing, as she does every night, and then stretches her hand across the Peppa Pig duvet cover.

Ruby-May slept tucked in a tight curl, like a fern frond before it unrolls.

She touches the spot where Ruby-May’s toes would have been.

She can’t imagine anything more soulless than a child’s empty bed at night.

Matt used to make her leave their daughter’s room, but he’s given up. On her or on himself, she’s not sure. Sometimes she still spends the night here, but every trace of Ruby-May’s smell has gone. She glances at her watch and tells herself that she needs to make an effort. We’re going out, for the first time in over a year. She forces herself to get up, to put the doll down, to hold back her tears. But instead of going to her husband, she slides Peter Rabbit and The Tale of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle forward and, with one finger, hooks out the bottle. It’s a cheap one from Aldi and, over the artificial juniper, she can smell the sharpness of neat alcohol. She takes a sip and then another, and feels the warmth bloom across the back of her throat: a line, like a burn, running down her chest. One more and then she replaces the bottle and smooths the pillow. Her skin is so dry, her knuckles catch on the cotton.

In one month, it’ll be a year. A year since their youngest daughter died. Ruby-May, the brightest jewel, her gorgeous girl. She’d always wanted Ruby-May to have her surname and not her husband’s – Ruby-May Flowers sounds so much more romantic than Ruby Jenkins. She can’t even bring herself to imagine the anniversary. It falls on the day before what would have been Ruby-May’s fourth birthday.

I can’t be here. I can’t do this any more.

The books all say that time heals. But nothing can cauterize her pain.

Matt doesn’t look up when she walks into the sitting room. He’s hunched over his laptop, catching up on work emails. Once, he’d have told her how nice she looked. She doesn’t look nice any more, though, she thinks. Maybe it’s not something he even considers any longer.

‘No sign of him?’ she asks, although it’s obvious Nick hasn’t turned up.

‘No. Have you called him?’

She’s already sent him one text and now she sends another, still trying for cheery and not as if she’s blaming him.

‘Just ring him,’ says Matt. ‘I’ve already had to pay a late fee to Uber.’

She goes into the kitchen where the signal’s better and stands by the window into the garden. Nick’s mobile goes straight to voicemail.

‘Nick, I hope you’re okay? We’re ready! The reservation is… well, it’s now. Can you give me a call, let me know you’re on your way?’

She phones the restaurant and puts the reservation back by half an hour. She checks there are still Ubers in their area. Matt could always drive, if there aren’t any when Nick finally turns up. She opens one of the drawers in the kitchen and takes a mint out from the packet hidden under the box of bag clips and bottle openers.

She stands in the sitting-room doorway and watches her husband. His hair has gone silver around the edges and there’s the beginning of a bald patch on his crown. She can’t be bothered any more. It’s all so pointless. She’s about to say they should just stay in, when Matt gets out his phone. He goes over to the window.

‘Nick, mate. Where the hell are you? Get your arse over here.’

She joins him on the window seat. It’s like a microclimate: cooler than everywhere else in the house. The sun is setting and there’s a pink streak over Bristol’s skyline. The room is scattered with bits of plastic – Lego and Octonaut figures, Sylvanian Families animals and a Playmobil zoo – which don’t quite obscure the fallen glasses and dirty cereal bowls. She should tidy it up, but her bones feel weary.

‘Shall we…’

‘Yeah,’ he says.

He goes into the kitchen and she can hear him banging cupboards, turning on the oven. He filled the freezer with readymeals and packets of frozen vegetables when she lost the will to cook. He comes back with two glasses, a bottle of wine and a pack of tortilla chips.

When he switches on the TV, her sister’s face fills the screen. Bethany’s talking animatedly, her dark, glossy hair swinging. She’s wearing navy nail varnish and skinny black leather jeans with a sheer blouse. You can see her bra when she leans forward and the studio lights shine through the fabric.

‘Must have been her last one,’ says Matt, turning up the volume.

Amy feels, as she does every time she sees her sister, a kind of cringing embarrassment: not because her sister is terrible – she isn’t, she’s good at what she does – but at the thought of being on live television, of having to say the right thing without stuttering, whilst somebody else is talking in your ear at the same time as you’re trying to listen to a studio guest and make intelligent and witty conversation or read the autocue. She would hate it – the scrutiny, and the effort it takes to look like that: not a chip in her polish, not an eyebrow hair out of place. Bethany once showed Amy her Twitter feed after a show, and it was a deluge of comments about what she was wearing, how she looked and what the male viewers would like to do to her. Amy had been horrified, but Bethany had just shrugged.

‘You should see my Facebook messages. Anyway, it means they’re watching,’ she’d said.

And now, of course, what she feels for her sister has become more complicated.

The doorbell rings and Matt pads through the hall in his socks to let Nick in.

‘Nick Flowers, you’re an hour late.’

‘I’m sorry, mate. I was in the studio and lost track of time.’

‘And you had your phone turned off?’

‘Had it on silent. You know what Tamsyn’s like.’ He comes into the sitting room, shucking his coat onto the sofa, and hugs her. His stubble grazes her cheek. ‘I’m really, really sorry, Ams. You can still go. I can stay as late as you like.’

She can’t remember the last time he was here. She doesn’t want to try. Was it really almost a year ago? He’s met them in cafes, and taken the children to the park. But he hasn’t been in their house for more than a few minutes. She guesses it’s because he can’t bring himself to walk past Ruby-May’s bedroom, which she’s left almost exactly as it was, one year ago.

‘Matt’s put something in the oven.’

‘Lasagne,’ says Matt. ‘Do you want some, now you’re here?’

‘Guys, I feel terrible – making you miss.…’ He catches sight of Bethany. ‘That’s The Show, right?’

‘It’s an old one. We had it on catch-up,’ Amy says. ‘Did she ever tell you why she left and came back to Bristol?’

Nick sits on the sofa, and Matt hands him a glass of Merlot and tops up hers. Nick shifts uncomfortably. He must have been in touch with Bethany.

‘You know what Bethany’s like. She probably changed her mind about working on it. Or fell out with someone.’

‘That’s more like it,’ says Matt, going into the kitchen. ‘She never got on with that new girl, did she?’ He hesitates and she knows he wants to say The brown one, but Sara knocked that kind of thing out of him. ‘The one with the Scottish accent,’ he says after a beat. ‘Tiffany MacGregor or something.’

He reappears a couple of minutes later with a tray; plates of gloopy slices of lasagne and peas; another bottle of red.

‘Thanks, Matt,’ says Nick, passing a plate to Amy.

‘How’s work?’ Matt asks.

‘Same. Tamsyn breaks my balls on the days she wants me in the studio, but then I can go for a week without any work.’

‘You should set up on your own. Take control of your life.’ Matt shovels in a sloppy forkful of pasta. ‘Do an MBA or a course on entrepreneurship. Can even do them online now.’

Her brother doesn’t even bother responding to this. Once he’d have given Matt a playful punch and told him he’d got into photography because he wanted to be an artist – not a suit, like him.

She eats listlessly, hardly tasting the food, and after she’s had a couple of bites, her stomach starts to convulse, as it always does at this point. Bethany is talking about holidays: apparently Croatia is the new destination; she raises her carefully groomed eyebrows archly. When was this filmed? May? It’ll be the summer holidays in a week and Amy hasn’t thought about where they’ll go or what they’ll do with the children, once they’re off school. She sets her plate aside. Nick glances at her and frowns, but doesn’t say anything.

Bethany’s voice – low, husky, as if she’s secretly smiling – tells them of Croatia’s exotic azure waters and rocky coastline, but how you can still buy English classics – beer and chips – on the seafront. The camera (they must have hired a drone) zooms over the cliffs and across vineyards and lines of dark, conical trees.

‘It’s almost the… the – it’s nearly a year since…’ says Nick. ‘I was thinking we should do something.’

It’s as if her younger brother has said exactly what she was thinking.

‘We could go away,’ Amy says. ‘Hire a holiday house and be away for… be away for—’

‘A holiday?’ Matt says. ‘Really?’

‘I can’t be here,’ she says. ‘You know that.’ Her voice rises.

The thought of being in this house, pretending to be cheerful for Theo and Lotte, fills her with a kind of panic. What would they do? Buy flowers, field condolences, all whilst trying not to think of her daughter as she last saw her, her lips swollen, her skin grey, her fingertips wrinkled…

Matt covers her hand with his own.

‘And we can’t go to Somerset.’

‘No,’ he says. ‘Shall we talk about it later?’

‘Italy. Italy would be perfect. It’ll be sunny. It won’t be remotely like here. The children will love it – they’ll have a good time. Somewhere with a beach.’

‘There won’t be any flights or villas left,’ says Matt. ‘We’ve left it too late.’ He’s been eating mechanically. It’s a new habit, to make sure he has ingested enough ‘nutrients’ to satisfy his doctor. He methodically spears the last of his peas onto his fork and takes a gulp of wine to force down the food. She can’t be bothered to talk to her GP any more.

‘No one will be able to reach us. I won’t have to speak to anyone asking how we are.’

‘We could get something online,’ Nick says. ‘Loads of people are letting their houses privately now, on Airbnb, that kind of thing.’

Matt reluctantly sets down his fork, as if he’s accepted that he’ll have to discuss Ruby-May’s anniversary in front of Amy’s brother.

‘Do you mean the… the five of us,’ Matt says, gesturing towards Nick, ‘plus Chloe?’

Chloe, Matt’s daughter from his previous marriage, is almost sixteen. Amy nods doubtfully. She might not want to come. Matt hasn’t counted Bethany. Or their dad.

‘I’ll ask Sara.’ Matt still sounds unconvinced. ‘That’s if we can find flights, and somewhere to stay, at such short notice.’

‘It’s in a month, not next weekend,’ Amy says and Matt gives her a dull look. She never used to speak to him like that, and she wonders if Matt mentioning his ex-wife has set her off.

‘What if,’ Nick says, swallowing his pasta, ‘what I meant was, what if we all went? The whole family. We should do something, you know, on the day. Together.’

He can’t say the word, either. An anniversary has always been a joyful occasion: the anniversary of when she and Matt first got together, their wedding anniversary.

‘All of us?’ Matt asks again.

‘It’s not like we’ve seen each other much. It might help, you know?’ Her brother clears his throat. ‘I’m not sure how – well, how else are we going to get past this? We’ve only got each other, since Mum left, and Dad…’ He tails off.

‘Including Bethany?’ Matt’s lips are set in a thin line.

‘I’ll talk to Bee,’ Nick says.

Matt glances at Amy to see how she’s going to react. When she doesn’t say anything, he picks up the plates and balances them in a messy tower, stacking them on top of the forks.

‘Come on, guys. She needs to be there.’

Matt carries the debris from their meal into the kitchen. Amy squeezes her eyes shut.

‘Amy, she’s your sister. She’s devastated by what happened. Have you even seen her?’ Nick asks.

She shakes her head. ‘A couple of times since the funeral. She thinks I hate her.’

‘Understandable,’ Nick says. They sit in silence for a moment. She doesn’t know if he means it’s understandable they haven’t met up, or understandable that she can’t bear being with her sister any more. ‘I know what she’s doing, from following her on Instagram,’ he adds. ‘You two were always closer than me and Bee. You can’t let that go.’

He’s right, of course. Her sister, who is thirty-four, is only two years younger than her. Nick was the baby of the family. He’ll be thirty this year. The kitchen door slams as Matt goes into the garden. He used to love it: on fine evenings he’d potter about out there, mowing the lawn, digging over flower beds, scrubbing the algae from the patio paving stones. Now it’s feral: a riot of bindweed and brambles; there are holes in the trampoline netting, and ash saplings have invaded the plant pots.

‘And what about—’

‘We can’t leave him behind.’

‘I can’t, Nick.’

‘It wasn’t his fault.’ Nick sounds like a robot. She’s lost count of the times he’s said that to her.

‘I don’t know how you can even say that. After what happened.’

He sighs. ‘He’s our dad. He’s getting older. We need to look after him.’

‘That’s not the point. If he’d only accepted that it was his fault and apologized.’ Nick looks down at his hands. ‘No. There’s no way he can come with us,’ she continues. ‘And don’t even think about asking Matt. He’d kill Dad, if he turned up.’ She takes a sip of her wine and rubs her eyes. ‘It’s a good idea to go away, though. I don’t want to stay here with the kids on my own.’

The credits to The Show start rolling over Bethany, her male co-star and the new girl – Tiffany – who seems to have replaced her. Bethany is waving manically.

‘Bethany Flowers,’ Nick says in a faux announcer’s voice, as if their sister were a movie star. And then in his normal voice he adds, ‘I don’t think she likes being on regional telly. Not quite the viewing figures. Do you want me to ask her about going on holiday?’ He glances sideways at her. ‘Assuming Matt agrees.’

Amy nods. ‘He’ll have to. I’ll speak to Luca too.’

‘Luca?’

‘His family live in Italy. He might come for a few days, help with Lotte and Theo, so we can have a bit of a break, and then he could go and visit them. He should be with us anyway. He’s almost part of the family, after all this time.’

Luca is studying for an MSc in child psychology and helps them with the school run when he’s not at university. He used to look after Ruby-May while Amy is at work. Nick nods, although Amy wonders if her brother has spoken to Luca since last year. He might not even have talked to him when they were in Somerset for Ruby-May’s birthday. The police had already arrived by the time Nick turned up. She can see the top of Matt’s head silhouetted against the darkening sky. He’s sitting on a broken bench just below them.

‘You can ask Bethany. Just don’t mention it to Dad. I should check on the kids,’ she says.

‘I’ll go,’ says Nick, ‘seeing as I’m meant to be babysitting them.’

‘If Theo is still awake, don’t stay there chatting to him about spaceships,’ Amy says. ‘Or Star Wars, Star Trek or intergalactic space flight, in any way, shape or form.’

She watches Nick hesitate at the bottom of the stairs, as if bracing himself, and then he jogs heavily up. She goes to the window and stares down at her husband, wondering if they can resurrect this evening, maybe put a film on. Go to bed early and try and summon up some passion, or even some semblance of feeling for each other. She should go out to him. She wonders if he knows about the bottle of gin in the garden shed (that one’s from Tesco and tastes even worse). But as if he feels her watching him, he returns to the kitchen, walking with the slow, stooped hunch of someone much older, and starts stacking the dishwasher. She’s relieved she won’t have to pretend, and pours another large glass of wine. She drinks it fast, without tasting it.

ONE YEAR AGO, SOMERSET

2

NICK

As far as I know, it happened like this. To my shame, I wasn’t there when it mattered.

Of course you weren’t! Bethany would interject, if she were here now. You’re always bloody late!

They’d all travelled down on the Friday and I could have got a lift, but I was working. I planned to go that Saturday morning but, thanks to my catastrophic timekeeping, I missed my train. The next one left an hour later and stopped at every hole in the wall and that, I guess, is why I wasn’t there when it counted. Still, at the time, I was pretty pleased with myself, because I’d found this toy unicorn with purple fur, massive sparkly blue eyes and a rainbow horn that I knew Ruby-May would love. I still have it. I suppose I should give it away, but I don’t like to think of another child playing with it.

It was 15 August, the day before Ruby-May’s third birthday, and everyone had gathered at Dad’s. The Pines is a rambling farmhouse that our parents, David and Eleanor, converted years ago, and although it no longer has the land it came with, it still has a huge garden. It sits on the lower slopes of the Mendips in Somerset, the woods behind, green fields gently falling away in front of it. On a good day – and 15 August, with its clear blue skies, was one of those days – you can see over the tops of the seaside towns of Clevedon and Weston-super-Mare and all the way across the Severn estuary to Wales. It’s where we grew up, Amy, Bethany and I.

That afternoon, Amy, my eldest sister, and her husband, Matt, drove to Clarks Village in Street. The Clarks factory, where they make their famous, sensible shoes, is there, as well as an outlet mall. They took their oldest two children with them, Theo and Lotte, so they could buy them a cheap pair each, ready for the new school term at the start of September. Amy wanted to pick up some extra things for the party too – she’d made the birthday cake and she had some sliced white for the children’s sandwiches, but she thought she’d get a quiche, posh crackers and cheese, and sparkling soft drinks made out of insane combinations of fruit and flowers, which no one in their right mind should buy. At least that’s what I imagine she wanted. I can’t believe she would have given Ruby-May a bought cake back then, even though afterwards she couldn’t manage to heat up a ready-meal. Or eat. They left Ruby-May behind. The toddler would have caused chaos in the shop, and as she was only going to nursery in the autumn, she didn’t need new shoes.

Our middle sister, Bethany, had offered to look after Ruby-May. Bethany’s good with children. She’s a TV presenter, so you can imagine that her over-the-top energy, disregard for rules and ability to perform on demand goes down well with small people. So that afternoon, as I was inching across the countryside, Brean Down a gleaming Arthurian mound in the distance, Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut playing on my iPhone, Amy, Matt, Lotte and Theo were in Street looking at shoes, and Bethany, Ruby-May and Dad were at The Pines. Dad is in his seventies now and is not as sprightly as he was. He spent most of the afternoon dozing on a wooden sun-lounger in the herb garden at the front of the house: it’s a real suntrap.

I should mention at this point that they weren’t the only people at The Pines. Matt’s teenage daughter, Chloe, from his previous marriage, was sunbathing next to Dad. After a while, she grew bored and went indoors – to do her homework, she said, but she was probably attempting to hook up with her friends over the lousy Internet connection. I found her half-empty glass of lemonade later, abandoned by the garden table, with a striped straw and a drowned wasp in it.

The only other person who was there that day was also inside. Luca – Amy and Matt’s ad-hoc childminder. The master’s degree he’s studying for is in child psychology, although I’m not sure how relevant that is, but his ability to relate to kids is probably why Ruby-May loved him so much. Matt has to leave the house by 7.30 a.m., and Amy has a part-time job as a charity fundraiser, so for three days a week Luca took Lotte and Theo to and from school, and looked after Ruby-May. I guess he’d have taken her to nursery that September, if things had turned out differently.

I learned all of this later. At the time I wouldn’t have known the minutiae of their daily lives and I’d never met Luca. I usually just turned up with sweets and caused chaos. That’s what uncles do, right? Anyway, Luca was there to celebrate Ruby-May’s birthday and maybe have a break from Bristol and enjoy the countryside. That morning he’d got up early and gone for a run.

At least, that’s what the police told me.

Luca is tall and rangy, and I imagine him loping through the dawn-stretched shadows across the dew-soaked fields. He said he spent the rest of the day in his room, studying.

I say his room, although it was actually Eleanor’s, our mother’s. She used to paint there because it has the best light in the afternoons – it’s at the front of the house, but at the far corner. You can see part of the herb garden from one of the windows, and glimpse the lines of thyme that she sowed in the cracks between the paving stones. Now it’s the spare room: Dad painted it white, even the floorboards, and a rug covers the worst oil-paint stains. When the sun warms the wood, I can still smell the linseed.

I don’t go in there much.

I’m procrastinating.

So, as I was saying, Bethany was playing with Ruby-May. They would have gone outside. Bethany doesn’t like being cooped up or staying still. And it is an amazing garden if you’re a small child and you’re fearless, or haven’t yet learned to be fearful. Bethany would have been tearing around the place: hide-and-seek in the orchard, singing and swinging Ruby-May on the rope strung from the large tree in the corner, racing across the lawn, mooing at the cows in the field at the end. She doesn’t have the patience for imaginary games, so they probably avoided the wooden Wendy house with its teaset laid out ready for a pretend birthday party; and I can’t believe she’d have gone near the ruins of the old cottage, after what happened there when we were kids. She also avoided the pond.

The pond is large, for a garden. In summer, when the water level dips, it still comes up to my waist. Our mother designed it: that August, the flags had finished flowering, but there were water lilies and dragonflies patrolling its borders. Eleanor used to sit on the sloping bank on a mossy bench and paint it. Once we were born, she refused to have it filled in, although Dad said a child can drown in just two inches of water. Maybe even then he didn’t quite trust our mother’s maternal instincts.

Dad had the local builder put up a low fence around the pond: it’s high enough to deter a small child, and he installed a gate with a Yale lock on it. You need a key to open it. Eleanor hated it and stopped painting the water lilies. No loss to the art world, I thought, when I was younger. It’s not like she’s bloody Monet. But I know now that some artists still hold it against my father. It was all part of the story they told about him: how he tried to lock Eleanor up, hedge her in. Control her. Make her look after her own children.

That afternoon Bethany saw she had several missed calls. The phone signal is terrible at The Pines. Because she works in TV, there’s no such thing as a weekend. The producers, the researchers, her agent all call her any time of the day or night. I thought it was an affectation back then. Bethany was working on a high-profile TV programme called The Show. Very meta. It was prime time, BBC1, but a new co-presenter had just been brought in, who was younger, bouncier, bubblier and mixed-race with a Scottish accent – the BBC was trying to up its diversity quota. Tiffany McKenzie. I thought Bethany was being an insufferable diva and didn’t want to share the spotlight; I didn’t realize what she was going through.

Sometimes, in the early mornings, it’s as if there’s a film projected against my eyelids: Ruby-May is a blonde blur, streaking through the orchard, her long hair stretched out behind her; the grass is preternaturally green, sun sparks off the red Katy apples and a cloud of rooks is flung across the sky.

Bethany woke our father and deposited Ruby-May on his lap. She told him to look after his granddaughter for half an hour while she went inside and made some calls on the landline.

It was more like an hour by the time she’d finished talking to her agent, the director of the shoot, the producer, the executive producer and then her agent again, to complain about what the director, the producer and the executive producer had said, and no doubt she also had to coordinate with her personal make-up artist, because The Show had axed hair and make-up during the latest round of cost-cutting.

The garden was unusually quiet when she went back out, blinking at the harshness of the sun after being cosseted by the dim light filtering through the mullioned windows into our dining room. She walked round the house to the herb garden and saw that Dad was still there, slumped in the sun-lounger, fast asleep.

There was no sign of Ruby-May.

JULY, BRISTOL

3

NICK

I’m walking to the studio when Amy calls. For once, I’m not late. I meant to get in early, though, to Photoshop the pictures from last week’s shoot and catch up on invoices for Tamsyn. The lowlying mist over the river is rapidly being burned off by the sun. I pass Underfall Yard and head towards the marina. Tamsyn’s studio is near Spike Island, an artists’ cooperative, where my ex-girlfriend Maddison makes her hip screen-prints, and almost next door to a historic ship, the SS Great Britain. I took Ruby-May, Lotte and Theo there last year for one of my uncle-outings. Ruby-May loved it: she ran around the ship screaming, pretending to eat the fake jellies and occasionally getting lost by hiding in the cabins (I didn’t tell Amy that part), but Lotte wasn’t so keen, and she and Theo had nightmares for a week afterwards. There’s a butcher’s room with models of flayed animals strung from their heels, including a dolphin. The kitchen was swarming with stuffed rats and smelt of fish, and the neighs of a panic-stricken horse reverberated through the dark hold. Quite clever really, but I suppose living on a ship a few hundred years ago (I don’t actually know when, I didn’t read the blurb) was pretty grim. Amy had been annoyed: What were you thinking, Nick?

Amy tells me she’s found a beautiful house, on an island off the coast of Italy, that’s ‘incredibly reasonable for August’ and is big enough for all of us. It’s got a swimming pool and it’s near a quiet beach. There are direct flights to Pisa from Bristol, and then you catch a train to the coast and a ferry. She’s got it all worked out. I’m surprised that Amy’s found somewhere so fast, but I guess I shouldn’t be, as she always used to be dynamic and organized. Before. I know it was my idea that we gatecrash Amy’s holiday, but I’m not sure I can afford it. ‘Incredibly reasonable for August’ sounds like code for ‘too much for a photographer’s assistant’. I have to be there, though. I’ll ask Tamsyn for some extra work or an advance on my laughable salary. I wonder whether Matt is happy, or at least not suicidal at the prospect of a holiday with the Flowers.

‘Have you talked to Bethany yet?’ Amy asks. ‘I need to book it, if she’s coming, or find a smaller place if she isn’t.’

‘I’m on my way to see her.’ I hesitate. ‘Amy, have you thought any more about—’

My sister’s voice sounds raw, as if she’s been crying, but her tone is final: ‘We don’t want him to come with us.’

This area, once so rundown with abandoned factories and the remnants of the boat-building industry, is going through a resurgence. Though I guess not for the boat yards. There’s a new tapas bar on the opposite side of the Avon that looks like it should be in San Francisco; blocks of flats have sprung up: with their white walls and jaunty-coloured window ledges, they’re reminiscent of cruise liners; the old gasworks has been converted into luxury penthouses, all steel and sepia-tinted glass. The flat my father used to live in during the week, when he was working at Bristol University, is perched up on the hill behind – he’s letting me stay there for now. Bethany, after she left home, had a better offer and went to stay with one of Dad’s friends – some prof with a posh house in Clifton – instead. Now she’s renting one of those apartments nearby that were swanky about a decade ago. It’s off Caledonian Road and is so close to the studio, we could hang out, if she liked me more than she does.

When I call my sister, she answers on the first ring, with a ‘Haaaaay’, like I’m her favourite person. ‘It’s Mr Nick Flowers.’ She sounds far too chipper for this hour in the morning – and for a conversation with her brother, when we haven’t actually spoken much for months.

‘Do you want a coffee? I’m passing – on my way to work.’

Only a small lie, as I’m walking in the opposite direction, but I don’t expect Bethany will stop long enough to figure it out.

‘I’m with Joe,’ she says, like I should know who that is.

Her boyfriend? That was fast; she hasn’t been in Bristol long. I can hear a man’s voice in the background.

She laughs. ‘Chill. It’s my brother.’

A jealous boyfriend?

‘We’re about to do HIITs on the towpath. Joe thinks you’ll distract me. So yeah, get us an espresso from that caff past Wapping Wharf. Make that two – Joe wants one. Apparently caffeine blitzes fat.’

I duck down Gas Ferry Road, alongside Aardman Animation and Tamsyn’s studio, and come out by the place Bethany’s talking about, which is basically a shed on the waterfront. As I reach the river, a girl with a swishy blonde ponytail in a kayak speeds past. Bethany and Joe are doing short sprints and then pausing. Joe is holding a phone that beeps when the intervals start and stop; I figure he must be her personal trainer. He’s wearing baggy black shorts and nothing else: he’s completely ripped. I hate him already. Bethany is in Lycra and a baseball cap and shades, as if she really is famous and might be papped at any second. I sit on a stone bench with the espressos and wait for them. When they stop for a few seconds in between their shuttle runs, Bethany drapes an arm around Joe’s shoulders and takes a photo of the two of them. He’s glistening with sweat, she’s all cleavage popping out of her sports bra, the sun sparking off the edge of her Oakleys. Joe pulls away and counts more loudly to the next interval, as if he’s annoyed with her for not taking this seriously.

When they’re done, they jog over, breathing heavily.

‘Hi, I’m Joe,’ he says, putting out his hand to shake mine. ‘Thanks for the coffee. Can I give you some cash?’

Bethany waves this away on my behalf. So he’s polite as well as good-looking; he has brown, curly shoulder-length hair, large dark eyes that slope down at the corners, designer stubble and a massive grin. He looks like a puppy and it’s impossible to dislike him, especially as he pulls a T-shirt out of his back pocket and puts it on, so that I don’t have to stare at his abs. I can’t remember ever actually seeing mine, even when I was a kid.

‘We’ve got another half an hour to go,’ says Bethany, taking a sip of coffee. ‘Got to get my money’s worth,’ she adds, elbowing Joe. She finishes sending the photo to Instagram and shows us the picture. The likes are already flooding in. She has one of those blue ticks next to her name, so you know she’s the real Bethany Flowers, and she’s got more than 100K followers.

‘It’s not like you to be sociable at this hour.’ She looks at me pointedly, as if to say, Or after all this time. ‘It’s the anniversary, isn’t it? It’s coming up soon.’

I nod, my throat suddenly dry. I tell her about our plan, to go away together to Italy.

‘Frankly, I’d rather hack off my own arm with a blunt penknife, but I get why she doesn’t want to be here. I’m not going, Nick. I’ve only just started this new job at the BBC and I can’t ask for time off already.’

‘Italy?’ says Joe, sounding childishly excited. ‘Whereabouts?’

Bethany rolls her eyes.

‘An island off an island. It sounds pretty cool. Remote, rural. The “real” Italy.’ I do air quote marks. ‘Beautiful sandy beaches. Pizza every day. Beer; no, hang on, what do you drink? Prosecco on tap.’

Joe does a thumbs up at me behind Bethany’s back. I think back to last week. It was the first time I’d been to Amy’s house for, well, ages; it was the first time she’d asked me to babysit for over a year, and I’d shown up late. It reminded me of what I’ve been missing: my family. I might find it hard to be with them some of the time, but I can’t manage another year like this one.

‘I’ll tell her you won’t speak to your new boss about taking a week off so that you can be with your family for the anniversary of the death of your three-year-old niece,’ I say.

‘You shit.’

‘Whoa,’ says Joe. ‘Bee, you’ve got to be there! Family is the most important thing there is,’ he adds, his expression earnest.

That was too much. I change tack. ‘Anyway, aren’t you freelance? And the star of the show? It’s good for your image if you aren’t always available.’ She narrows her eyes, trying to assess whether I’m taking the piss. It might still be regional telly, but the new show she’s presenting has almost a million viewers. ‘With your powers of persuasion you’ll have your new telly chief wrapped around your little finger in no time.’

‘Stuart Linfield is the exec, and there’s no way. Quit now, before you come up with any more crap.’

‘I don’t want to be there on my own?’ I make it into a question, as if I’m trying out the line for size.

‘Ah,’ she says, punching me on the shoulder, ‘that’s the real reason.’

‘Come on, where’s your sense of adventure? At the very least, you’ll get a tan.’

‘Sense of self-preservation more like.’ She pauses. ‘Is Dad going?’

I shake my head and for a moment there’s silence while we both look at our feet. If our father hadn’t been looking after Ruby-May, our niece would still be alive, an almost-four-year-old, believing in unicorns and dreaming of being an astronaut. I don’t say it because, well, it wouldn’t help, but I think about it all the time; and I guess Bethany probably does too.

She avoids my eyes. ‘Probably for the best.’ She suddenly swings round. ‘Hey, Joe, why don’t you come with us?’ He looks floored and glances at me, but Bethany carries on talking. ‘I’ll need to keep training. And we could do those photos you were talking about for the book. Nick’s a photographer. He’ll take them. Joe wants to write a book,’ she tells me, speeding up, her words scrambling out of her. ‘He’s got to write a synopsis and add some photos, to pitch it to a publisher. We could shoot them on the beach. I’m going to write the introduction.’

‘It doesn’t seem appropriate,’ says Joe, pushing his hair off his face.

I notice he’s wearing an Alice band, like Lotte’s, but it’s not particularly girly on him, in spite of his long hair.

‘You don’t need to be there for the… for the anniversary. Just come for a few days. Two or three. Think of it like a working holiday. We’ll come up with the pitch. We’ll do our workout in the mornings and you can chill in the afternoons.’

‘What do you think?’ Joe asks me.