8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

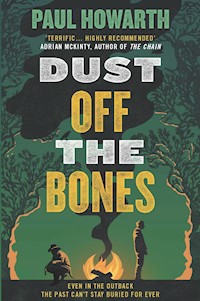

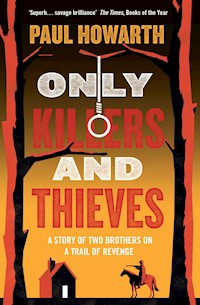

Set in the searing, deserted outback of 19th century Australia, a powerful debut novel about family, empire and race One scorching day in Australia's deserted outback, Tommy McBride and his brother Billy return home to discover that their parents have been brutally murdered. Distraught and desperate for revenge, the young men set out in search of the killers. But the year is 1885, and the only man who can help them is the cunning and ruthless John Sullivan - wealthy landowner and their father's former employer. Rallying a posse of men, Sullivan defers to the deadly Inspector Noone and his Queensland Native Police - an infamous arm of colonial power whose sole purpose is the 'dispersal' of Indigenous Australians in 'protection' of settler rights. The retribution that follows will leave a lasting scar on the colony and the country it later becomes. It will also haunt Tommy for the rest of his life. Set against Australia's stunningly harsh landscapes, Only Killers and Thieves is a compelling, devastating novel about cruelty and survival, injustice and honour - and about two brothers united in grief, then forever torn apart. Paul Howarth was born and grew up in the UK before moving to Melbourne in his late twenties. He lived in Australia for over six years, gained dual-citizenship in 2012, and now lives in Norwich with his family. He graduated from the UEA Creative Writing MA in 2015 and was awarded the Malcolm Bradbury Scholarship. Only Killers and Thieves is his first novel.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

For Sarah

‘[He], with his little band of black boys at his heels, inspired the aborigines with such a wholesome dread, that it was only necessary, when on any of their marauding expeditions, to say [his name] and they would go yelling pell-mell into the bush.’

—Description of a Native Police officer inThe Queenslander, 13 February 1875

CONTENTS

CENTRAL QUEENSLAND, AUSTRALIA

1885

1

THEY STALKED THE RUINED scrubland, searching for something to kill. Two boys, not quite men, tiny in a landscape withered by drought and drenched in unbroken sun. Vast plains pocked with spinifex and clumps of buckbush, grass brittle as old bone, red soil fine as gunpowder underfoot. There’d not been rain for a year. The whole bush smelled ready to burn. Dust blew in rivulets between the clutches of scrub and slid in great sheets over open ground. No cattle grazing here. What remained of the mob was down valley, closer to the creek, where the water ran in a trickle through a trough of dry mud and the surrounding floodplain offered the last of the feed. Now all that lived in these northern pastures were creatures meant for the terrain: lizards, snakes, spiders; possums, dingos, roos. Often there’d be rabbits but even the rabbits knew to shelter from the afternoon sun. Only the flies were moving; there was nothing for the brothers to hunt.

They paused and stood together with their rifles down, grimly surveying the surrounds, breathing hard, the air too hot and thick to properly fill the lungs. The older of the pair took off his hat, wiped his brow with his wrist, spat. He settled the hat back on his head. It didn’t fit him well. The younger’s fit him even worse. Tommy and Billy were fourteen and sixteen years old, and both wore their father’s old clothes: tan moleskin trousers tied off with a greenhide belt, dark and sweat-stained shirts. They exchanged a weary glance and stood waiting. A light breeze blew. The shrill rattle of cicada screams. Flies covered the boys’ shirt backs and crept towards their eyes and earholes until a casual swipe of the hand flicked them away. That lazy stockman’s salute picked up from their old man, or something they were born with, maybe. Flies had been coming at them their entire lives; they’d been fighting them off since the crib.

‘Well,’ Billy said, ‘I reckon we might as well quit.’

‘She won’t be happy.’

‘She can please herself. It ain’t our fault there’s a drought.’

Tommy opened his flask, tilted back his head, eyes closed against the sun, and drank. The water tasted stale and metallic and caught in the back of his throat. He winced as it went down, a childlike revulsion against the taste. Still some boy left in him yet: whereas Billy now had stubble and their father’s broad frame, Tommy’s body was slender, his nose was freckled, his eyes a watery blue. His hair was fairer than his brother’s too, tints of red in a certain light, which came from their mother’s side. She was Irish, their father Scots, and there was English blood in both lines. If they were dogs they’d have been called mongrels. Australian was a whole new breed.

Billy held out his hand out for the water, Tommy passed it across, and as his brother drank Tommy’s gaze wandered over that barren and rubbled ground to the thin blue gum forest that marked the northern boundary of their run, shrouded in a fine eucalyptus mist.

‘Hey,’ he said, nodding. ‘Be shade in them trees.’

Billy lowered the flask. ‘I ain’t hot.’

‘Me either. I mean the rabbits. Might even find us an old-man roo.’

Billy scoffed, flicked water at Tommy’s face.

‘Don’t bloody waste it,’ Tommy said, wiping himself down. ‘That’s all there is left.’

‘Tastes like foot wash anyhow.’

‘Give it here then.’ Tommy took back the flask and stoppered it. ‘So, what about them trees?’

Billy considered it a moment, then set off walking north. Tommy followed. The cicadas fell silent. The only noise out there the scuff of their boots and whisper of their moleskins as they trudged through the rocky scrub. Tommy checked behind them as he walked. Mile after mile of empty terrain—it was already an hour’s walk back to where they’d tied the horses in a stand of ironbarks, might be half that again by the time they reached the blue gums, and then the long ride home. Most likely all for nothing. Neither had fired his rifle since they’d left the house just after noon, or even taken aim.

It was cooler in the trees. Shadow dappled the forest floor. Deadfall and leaves crunched underfoot, a taint of eucalyptus in the air. With their rifles raised the brothers began flushing between the trunks, some tall and white, others gnarled and twisted by the sun. They moved slowly. Scanning side to side, heads cocked to listen, silence all around. With the dogs they might have fared better, but Father had them for work. He never spared them: poor old Red and Blue.

Suddenly something bolted, crashing away through the brush, Billy first after it, Tommy just behind, both of them tearing between the trees, jumping fallen logs and bulging roots, carrying their rifles two-handed, ready to aim, but the thing was always beyond them, never a clear view, a shadow slipping through the sunlight, until even the sound was so faint that Tommy could hear nothing over his own ragged breathing. He slowed and then stopped, his hands on his knees, Billy coming back towards him, calling, ‘What you quit for? What’s wrong?’

Tommy shook his head. ‘It’s gone.’

‘We might have caught it yet.’

‘You get a look see what it was?’

‘Dingo, I reckon.’

‘Dingo would have fought us. That quick, likely an emu.’

They recovered their breathing, Tommy leaning against a smooth-barked trunk, Billy peering through the thinning trees to where the forest ended and the next tract of open ground began.

‘You know what’s over there?’

‘Course I do,’ Tommy said. Broken Ridge cattle station accounted for almost the entire district; excepting their own selection, and one or two others like it, there was not much this side of Bewley that wasn’t the squatter John Sullivan’s land.

‘Want to take a look?’

‘What for?’

‘You ain’t curious?’

‘We should be getting back.’

But Billy was already moving, weaving through the trees. Tommy let him go. He cleared his nose, took another drink from the flask. Billy called for him to come. He was standing at the tree line, waving like he’d discovered virgin land. Tommy sighed, trudged after him, then stood with his brother looking out over the fringe of a landholding a hundred times the size of their own. Broken Ridge was no selection: Sullivan’s grandfather had been the first white man to settle this part of the frontier, had taken all he could defend, no purchase, no lease, and the next two generations had pushed the boundaries further still. Now John Sullivan owned the entire district—and everyone in it, Father claimed—without so much as a shilling having ever been paid.

The immediate terrain was familiar: bare ochre earth scattered with boulders and scree, termite mounds as tall as a man. But where the land opened out and sloped into the valley, Tommy could see a distant meadow with what looked to be Mitchell grass growing improbably lush and green, the dark shapes of livestock dotted throughout. Beyond the meadow and the tree-lined patchwork of surrounding paddocks and fields, the jagged red ridge for which the station was named sawed against the sky, the foothills part-shadowed as if wildfire-scorched.

‘One man,’ Billy said quietly. ‘One man owns all of that. And here’s Daddy barely making it still. All these years, and we ain’t worth the dags on Sullivan’s arse.’

Tommy looked at him sideways. ‘You might not be.’

‘I mean it. When I get my own run…’

Billy drifted into silence, the dream of it, his long-held plans.

Tommy said, ‘We should go.’

‘We ain’t doing no harm.’

‘You know what Daddy would say. Anyhow, it’s a long ride home.’

Billy smirked at him, then stepped deliberately from the tree line, spread his arms and turned around. ‘See? What did you reckon, the ground would give out?’

He shouldered his rifle on the strap and swaggered away. Tommy cursed, ran after him, and together they wandered cautiously between rock mounds ringed by snake tracks, more clumps of spinifex, occasional mulga trees and Moses bushes and the flat-leaf tendrils of prickly pear. The valley opening before them, the pastures running on and on… it seemed incredible to Tommy that Sullivan’s land could be fed by the same creek that flowed barely shin-high on their own. Unless it wasn’t—there might have been another river that Tommy didn’t know. It was possible. Broken Ridge was big enough that there could easily have been two.

They’d been walking less a mile when Tommy saw the first horse coming over the rise. He threw out a hand and grabbed Billy by the shirt and pulled them both down to their knees, his eyes on the horse all the while. It was heading east to west, only five hundred yards away, and was ridden by a very tall man, sitting fully erect in the saddle, wearing a slouch hat and longcoat flapping open at the sides. After him came another rider, this one small and hatless, then a further five horses, seven in all, trotting in a single-file column. Trailing behind them were three native men chained together at the necks, running in the dust thrown up by the hooves and struggling to keep their feet. Whenever one fell the others did too, causing the convoy to halt and the rear-most rider to shout and curse and yank on the chain, hauling them upright in a clumsy jerking dance, whereupon the convoy would move forward until the next man fell, and the dance started over again.

All this the brothers watched wide-eyed, neither of them speaking, barely breathing so it seemed, until finally Billy took Tommy’s arm and dragged him in a crouch to a pair of Moses bushes growing side by side. They sprawled on their bellies and crawled underneath, thorns snagging their shirt backs and scraping their skin, wriggling far enough through to see the convoy again. Once more it had stalled. Another of the men had gone down. The rider yelled and pulled the chain, but this time there was no response. The group watched and waited. The rider got down from his horse. He was wearing a kind of police uniform, as were three of the others: white trousers, blue tunic, peaked hat. He walked over to the fallen native and kicked him. The native shifted in the dirt. The trooper slapped the other two about their heads, then kicked the man again. When still he didn’t rise, the trooper returned to his horse, pulled a rifle from his pack and looked towards the front of the line. The tall man nodded. The trooper stood over the native, aimed and fired.

Tommy saw the body flinch before the sound of the shot came tumbling over the plains. A noise escaped him. A soft and high-pitched breath. He could feel his heart hammering against the ground as the fading rifle report was followed by a muted cheer. The other riders were clapping. The trooper gave a little bow. He bent and uncuffed the body from the neck chain then bullied the remaining men into line. They rose cowering behind their hands. The trooper shook out the chain and remounted his horse, but the party didn’t move on. The front two men were talking. The tall man extended an arm and pointed to where Tommy and Billy hid. Other heads turned their way. Then all but the last horse broke into a gallop and fanned wide across the plain and Tommy gave out a moan like a just-kicked dog.

‘Keep quiet,’ Billy whispered. ‘Don’t move.’

On the horses came. The ground rumbled with their hooves. Billy was edging backwards and was almost out of the bush when Tommy realised he was gone. He pawed at his brother’s collar; Billy brushed him off and warned him again not to move. ‘Don’t!’ Tommy was saying. ‘Don’t!’ But Billy was almost out now, shuffling himself clear, the shock in his face like a man falling, clutching at the air.

Through the branches Tommy watched him rise slowly to his feet and lift his rifle above his head, barely the strength to manage it, his whole body wilting as the horses bore down, full gallop still, and not fifty yards away. Billy stepped into the clearing, everything trembling, his legs jagging back and forth, stumbling backwards as the riders reined their horses so late they were almost upon him, turning his head against the dust cloud that washed over him on the wind.

Two riders came out of the line, walking their horses slowly on. Tommy recognised both of them—John Sullivan and his offsider, Locke—but the troopers were like no kind of police he’d ever seen. They were black. Three uniformed natives, rifles in their hands, cartridge belts slung across their chests. The tall man in the longcoat was white and very slim; he kept back from the group and began with the makings of a pipe, as Sullivan and Locke drew up directly in front of where Billy stood. Sullivan was plump and red-faced and wore a stained and sodden shirt carved by braces digging into his chest. Thinning hair sprouted wildly from his scalp, and his little eyes pinned Billy in a glare. Beside him, Locke chewed on his tobacco like a cow at her cud, his face in shadow beneath the brim of his hat, stubbled jaw working up and down. A short-blade sword hung at his side; it glinted as he leaned in the saddle and spat a thick string of brown saliva onto the ground by Billy’s boots. Billy lowered his rifle. He lifted his eyes towards the men.

‘You would be one of Ned’s boys, I take it?’ Sullivan said.

‘Yessir, Billy McBride.’

‘And the other one? I forget now, which of you’s which?’

Tommy’s innards quickened. Billy glanced across but didn’t answer. Sullivan said, ‘Either he comes out himself or we’ll fetch him—however you prefer.’

Tommy’s head hung. He blinked into the dust. Dryly he swallowed, then with his rifle in his hand he shuffled out of the bush and walked meekly in front of the group, eyes down, couldn’t meet their stares. When he reached Billy’s side he stood so close to his brother that their arms and shoulders touched. Fingers brushing fingers; neither pulled away.

‘Well, it’s been a while,’ Sullivan said. ‘You’re almost fully grown.’

Father kept the children hidden whenever Sullivan came to the house, sent them to the stables, the barn, the sheds. It hadn’t always been like that—Tommy remembered the squatter once giving him a small wooden horse, which only years later had Father taken from him and burned.

‘So,’ Sullivan said, dropping the reins and folding his arms, ‘you want to tell me what you’re doing with them rifles on my land? Your old man send you up here? Not duffing my cattle, were you, boys?’

‘No, sir,’ Billy said. ‘We was hunting rabbits and got lost, that’s all.’

‘Got lost? Missed the tree line when you crossed it, did you?’

‘There was a dingo,’ Billy said hopefully. ‘Or a emu, we wasn’t sure. We chased it and forgot where we was. We wasn’t duffing, I swear.’

Sullivan sniffed and looked about, as if searching for proof.

‘Thing is, son, whether it’s a dingo or emu or bloody kangaroo, once it’s this side of the trees it’s mine to hunt not yours. Didn’t your father teach you where the boundary between us lies?’

‘Yessir,’ Billy said quietly. ‘But, ain’t them things everyone’s? On account of they’re wild?’

‘Sounds just like a nigger,’ Locke said. He twisted around to look at the two distant captives and the trooper holding their chains and spat.

‘No, son,’ Sullivan said. ‘No, they’re not.’

In the silence that followed, Tommy glanced at the tall man sitting at the back of the group. He was smoking his pipe and gazing without interest into the scrubs, smoke d ribbling from under his moustache and drifting over his face like a caul. His skin was stretched tightly over his cheekbones, and his eyes were soft and milky, no colour in them at all, fogged like a lantern whose wick has burnt out.

Sullivan said, ‘You’re wondering about my associates here… well, the man at the back there is Inspector Edmund Noone of the Native Mounted Police. These are his troopers. As I’m sure you know, their business is the dispersal of those who don’t belong. Chiefly that means myalls, but Mr Noone’s talents aren’t particular to the colour of a man’s skin: boys, he knew you were hiding in those bushes probably before you even got there yourselves.’

Noone turned his gaze on them. Tommy looked immediately at the ground.

‘Now usually,’ Sullivan continued, ‘Mr Noone will punish trespassers to the fullest extent of the law. To disperse them, as it were, as you have just seen. But since he’s here on my account, and since this is my land, I suppose I have a say. So, here are the terms: first, that I never catch you past them trees again…’

He paused and looked at Billy, who nodded eagerly in reply.

‘And second, that you tell your father what happened here today, understand?’

‘Yessir,’ Billy said. ‘Yessir, we will.’

‘And you?’

Billy elbowed Tommy in his side. He nodded.

‘He don’t speak for himself? To my thinking a deal should be agreed out loud.’

‘Say it,’ Billy hissed.

‘Yessir.’

‘Good,’ Sullivan said, taking up his reins. ‘Then on your way.’

The boys backtracked hesitantly, as one by one the group turned their horses and rode towards the trooper holding the two chained men. Only Noone remained. Still smoking his pipe, watching the boys like he hadn’t noticed the others leave. His gaze was steady and firm and his eyes were very white. Tommy felt that gaze run through him. It tiptoed down his spine. Billy tugged on his arm, pulled him away, and they set off scrambling for the distant trees.

The first time Tommy looked behind him, Noone was still there, watching. The second time he looked, he was gone.

2

WHEN THEY RODE INTO the yard Mother was on the veranda sweeping, fighting her perpetual war against dust. A thin woman with a thin broom, pale in the shade of the porch, beating the wooden deck. Every day she swept, often many times, driving the dirt from inside their slab-walled house and around the small verandah, then expelling it down the steps. She swept, she cooked; privately, she prayed. She carried eggs from the fowl house in the folds of her apron; she taught all of her children to read. She had a hankering for the city. For city values, at least. She was a country girl now but not by birth—somehow she’d drifted out here. First to Roma, then Bewley, then this parcel of frontier land she’d wistfully named Glendale. Other than the dead centre, there was nowhere further to drift.

As the two boys dismounted, she finished her round of sweeping then stood on the front steps with the broom in her hands and watched them walk their horses past the house, towards the stables, across the yard. Tommy felt his throat tighten. Still an urge to run to her, to confess, to allow himself to be held, but Billy had made it clear they weren’t to talk. Said Sullivan only wanted Father knowing because of the trouble it would cause. Mother smiled at them as they crossed in front of the house and Billy said it again, ‘Not a word, Tommy,’ but quietly, through lips pulled tight in a smile of his own.

‘Well?’ she called. ‘What have you brought me?’

‘Scrubs are empty,’ Billy replied. ‘There ain’t nothing left.’

She raised her eyebrows. ‘I’m sure Arthur would have managed fine.’

‘So send him out next time.’

‘Tommy—what’s your excuse?’

‘Sorry, Ma.’

She flapped a hand dismissively. ‘Ah, away with you. Useless boys. Me and Mary would fare better. Or maybe you just prefer my potato stew?’

‘Best this side of Bewley!’ Billy shouted. Mother laughed and shook her head and went back up the steps and inside.

They walked on. Past the long bunkhouse that had once held a dozen men and was now home to only two: Arthur plus the new boy, Joseph, Father’s native stockmen. The double doors were open but there was no one inside, and when they got to the stables the other stalls were empty, meaning the men were still out working, seeing to the mob. There wasn’t long before the saleyards: their year, their futures, tallied and sold.

In silence they unsaddled the horses, brushed them, fed them, tipped water on their backs, hung the damp blankets on the outside rail to dry. They walked down through the yard together, towards the well and the rusted windmill squeaking with each turn. Tommy fell back to let Billy have the first wash; he hauled up the bucket, watching Tommy as he pulled.

‘There ain’t no sense worrying about it. They never meant us any harm.’

‘You were scared the same as me.’

‘Only because of them natives. Bloody hell, Tommy—black police!’

Billy laughed nervously as he said it, dragging the bucket over the rim of the well and sloshing water onto the ground. He knelt and began drinking, washing himself down; Tommy stole fitful glances across the empty yard. Just the mention of them made him nervous, blurred memories of rifle muzzles and cartridge belts and the uniforms they wore. He hadn’t looked at their faces, hadn’t dared. Tommy knew nothing about the Native Police—Father didn’t like talking about trouble with the blacks. Over the years he’d heard stories about fighting in the district—the whole colony, in fact—from stockmen and drovers and the odd traveller passing through. But Father wouldn’t discuss it. Not their business, he said. They had plenty of their own problems without getting involved in someone else’s war.

Billy finished washing and stood. Tommy came to take his turn. He tipped out the bucket and threw it into the well, heard it clattering against the walls then splash into the water far below. He waited while it filled.

‘They probably deserved it,’ Billy said. ‘Might have done anything.’

‘Trespassing, Sullivan reckoned.’

‘All I’m saying is there ain’t no sense worrying about what we don’t know.’

Tommy didn’t answer. He held Billy’s stare. Billy shook his head and walked around the front of the verandah, towards the steps, and Tommy began pulling on the rope. He paused to listen to his brother’s boots on the verandah boards, the door slapping closed in the frame, then lifted the bucket clear of the well. He knelt on the ground and drank, the water dusty but cool, set about washing his face and neck and at one point sank in his whole head. He stayed under as long as he was able, eyes closed, listening to the tick of the wood and the beating of his own heart, a strange kind of peace in the confines of the pail, muffling the outside world. But then came a crack of gunfire and he saw the body twitch, the trooper standing over it performing his little bow, and in the silence of the water he heard the horses advancing upon them, the rumble of their hooves in the ground.

Tommy lurched out of the bucket, gasping, jerking his head around. The yard behind him was empty. There was laughter from inside the house. Mary’s voice, light and playful, some jibe at Billy’s expense. Tommy pushed himself to standing and collected his hat. Water ran from his hairline, dribbled off his chin. He kicked over the bucket, the dirty puddle seeping into the soil, then he walked around the side of the house scuffing the wetness from his hair. He paused. In the north, beyond the cattle yards, three horses were coming in from the scrubs, lit by the fading sunlight in a rich and golden hue. Father, Joseph, and Arthur, the dogs trotting with them, a thin dust trail behind. Tommy took a deep breath and let it out slowly through his nose. He walked up the steps and went inside.

* * *

They sat around the table, mopping potato stew with freshly baked bread, Mary bemoaning her brothers and the lack of meat in the meal. She was eleven years old but thought herself eighteen; round-faced, with her mother’s fair colouring, and little time for a woman’s lot. She’d been pestering Father to let her work the scrubs ever since she was able to ride. Now all she wanted was to go hunting instead of staying home with her chores.

‘And who would help me?’ Mother asked her. ‘Or do I grow another hand?’

‘These two galoots. Let them clean and sew and see to the chooks. We’d be eating a nice fat possum if you let me go out. Or a kangaroo.’

‘There ain’t no roos,’ Billy said. ‘Anyway, how would you get one back?’

‘Drag it if I had to, but I wouldn’t have rode so far.’

‘That was his idea,’ Tommy told them. ‘I never wanted to go north.’

‘Only to keep clear of the mob,’ Billy protested. ‘No other reason than that.’

Father sat back in his chair, chewing, a faint smile on his lips. He moved with a cattle man’s stiffness, and like all cattle men his eyes were narrowed in a near-permanent squint. He wore his beard short, his dark hair too, and the lines in his face looked chiselled from birth. Only a few years past forty, he had the weariness of a much older man. Like every day was a struggle. Which in truth it was.

Father folded his arms and looked between his children. He was sitting at the head of the table, framed by the last of the sunset in the open window behind. Enough daylight still that a candle could be saved, and no need for a fire just yet. There would be, soon enough, once the sun was fully down. The walls of the house were made of ill-fitting timber slabs, and the roof was shingled in bark, and both let in draught and dust and rain, if ever rain fell. Only the original building had a floor: the main room and a bedroom off it, separated by a blue curtain door. Annexed out back was another bedroom, where all three children slept, and an open-air scullery had been tacked onto the northern side. The whole dwelling leaned like a drunk on his horse, steadfastly refusing to fall.

‘Your sister has a point,’ Father said finally. ‘You had any sense you wouldn’t have been up that way at all. You’re as likely to find something in the yard.’

‘We did, though,’ Billy said. ‘Maybe a dingo or emu, we wasn’t sure.’

‘Well, they do look about the same,’ Father said. Mother and Mary laughed.

‘We couldn’t see it properly for the trees.’

‘Oh, aye? And which trees were those then?’

Billy fell quiet. Tommy lowered his eyes too. Father wiped his bread around his plate, leaned his elbow on the table and tore off a corner with his teeth. He chewed lazily, waiting. Mary’s head jerked between her brothers like a bird hunting grubs.

‘What’s the matter?’ she said. ‘Where’d you go?’

‘Nowhere,’ Billy snapped. ‘Just… trees.’

‘The blue gums up Sullivan’s way?’ Father asked, but Billy only shrugged. Father turned to Tommy. ‘You’ll have to answer for him. Your brother doesn’t seem to know where he’s been.’

Tommy felt Billy staring. ‘We thought there might be rabbits in the shade.’

Father leaned both elbows on the table, hunched over his bowl. ‘Might be a golden bloody goose for all I care, you stay away from Sullivan’s place, understand? You’ve the whole country to hunt in—why in hell d’you go up there?’

‘Cause they’re galoots, I already told you.’

‘Enough, Mary,’ Mother said.

‘What’s your problem with him anyway?’ Billy asked. ‘What’s he ever done to us?’

Father sniffed and sat upright. He popped the last of his bread in his mouth and said, chewing, ‘There is no problem. Just do as you’re bloody told. Bloke like that could shoot you if he caught you hunting on his land.’

‘We weren’t on his land,’ Billy said quickly.

‘Close enough. Don’t hunt in them trees again.’

‘They weren’t hunting, neither,’ Mary said. ‘They were taking a nice long walk.’

She laughed and Billy pushed her. Mary squealed and ducked away. Mother grabbed both of their arms and told them to settle and eventually they went back to their meal. Tommy paid no attention. He was staring into his bowl, watching the stew creep through the crumb of his bread, grain by grain by grain. He lifted the bread to his mouth but it collapsed into mush in his bowl. He glanced up and found Father watching him; Father rolled his tongue, shook his head, looked away.

* * *

He was woken by Billy kicking, fighting in his sleep. Tommy shoved him, rolled onto his back and lay listening to the tick and yawl of the scrubs outside and the catch in Billy’s throat when he breathed. The bed wasn’t wide enough to lie like this—his shoulder dug into Billy’s spine—but Tommy liked watching the stars through the gaps in the shingle roof. Sometimes there’d be a faller, and he would make a wish, but he never got to see one fall the whole way. The width of a crack and that was all. Like a match being struck in the sky.

He shivered, reached for the blankets, felt his nightshirt clinging damp against his skin. Though the night was cool he’d been sweating; might have been dreaming himself, maybe. When they’d first come to bed, Billy had accused him of dobbing to Father about them having been up in those trees. But Mary had been listening from her cot across the room, so they lay in sullen silence in the dark, until both fell asleep and they were at it again, arguing in their dreams.

Tommy swung out his feet and stood, crossed the room to Mary’s cot. She was huddled in her blankets, her mouth hanging open, spittle running from the corner of her lips. He smiled and turned away, paced up and down, rubbing himself briskly, trying to get warm. He paused by the doorway curtain. A faint light framed its edge: the fire was burning still. He pulled back the curtain, went into the other room and stopped just past the threshold. Though the fire was glowing, it was candlelight he had seen. Father was at the table, a bottle at his elbow, a glass in his hand, his pocket notebook open before him, the little red pencil resting in the fold.

Father looked up slowly. The light from the tallow candle flickered on his face. One half in darkness, the other in flame. He peered at Tommy a long time.

‘What is it, son?’

‘Billy’s kicking about.’

‘So kick him back.’

‘I did.’ Tommy’s eyes went to the hearth, and again he shivered. ‘Thought I might use the fire a while.’

‘You sick or anything?’

‘I don’t think so.’

Father gestured grandly towards the fireplace. Tommy came around the table and stood with his back to the embers, waiting for the warmth, avoiding Father’s stare. Father poured himself a drink and sipped it, offered the glass to Tommy. Tommy shook his head.

‘Help if you’ve a fever.’

‘I’m not sick, I said.’

Father nodded slowly, lips pursed, head rocking up and down. The fire spat and hissed. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘it felt earlier there was something you and Billy might be keeping to yourselves.’

‘Only that we were up in them trees. We knew it wasn’t allowed.’

‘Nothing else happened?’

‘Like what?’

‘Anything. You two have been off all night.’

Tommy shook his head. A quick little burst side to side. Father sniffed and drank again, hesitated, then drained the glass. ‘Ah, it’s not your fault. This ain’t no place to live, raise a family. I shouldn’t have to warn my own children off the bloody neighbour’s land.’

‘Weren’t you friends once? You and Sullivan?’

Father drew himself tall, scraped his palms over the tabletop.

‘Working for a bloke doesn’t make him your mate, Tommy. The opposite, in fact. That was a long time ago anyway; lots of things have changed.’

Tommy was about to respond when Father leaned on his elbow and pointed at him, continued, ‘A man shouldn’t answer to anyone. He makes his own way in the world. You understand what I’m telling you? Being a wage slave ain’t much better than being a blackfella; you’re both some other bugger’s boy. What you want is your freedom. Don’t give it away, Tommy. Not for any price.’

He wagged his finger then dropped it, rapped his knuckles twice on the wood. He closed the little notebook, laying one hand on top while the other poured a drink. Thoughtfully he sipped it. Staring into the candle flame.

‘How bad is it?’ Tommy asked quietly.

‘There’s a drought. The cattle’s starving. How bad d’you reckon it is?’

‘Will we be alright, though?’

Father looked up then. His eyes softened and his mouth pulled tight in a grimace, and he breathed out heavily through his nose. ‘Aye, we’ll be alright.’

‘But, they’re starving, you just said.’

Father reached for Tommy’s arm, pulled him close, then cupped the back of his neck and dragged him down until the two of them were butting heads. Tommy could smell the rum. He squatted awkwardly in the embrace, as Father brought his other hand around and slapped him on the cheek.

‘You know I love you, Tommy. That I’ll look after you, all of you, keep you safe. You make a decision you think is for the best and it’s too late when you realise it’s not. I’m bloody trying though, eh. Doing the best I can. All I need from you and your brother is to help with the work and do what you’re told, and we’ll get ourselves out of this mess. Reckon you can do that for me? Can you do that, son?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good lad,’ Father said, patting his cheek again. ‘Proud of you. Good lad.’

He released him. Tommy retreated to the fire. Father saw off his drink and pushed himself to his feet. The chair scraped on the boards. He picked up his notebook and wedged it into his shirt-breast pocket, then moved unsteadily around the table, holding the chairbacks as he went. The candle flame wavered in the disturbed air. The wick was almost drowned. Father lunged across the open space to his bedroom, paused at the curtain and said, ‘Busy day tomorrow. Don’t be late turning in.’

‘I’ll just wait till I’m dry.’

He looked at Tommy queerly. ‘Dry?’

‘It’s sweat,’ he said, smiling. ‘It’s only sweat, that’s all.’

Father returned the smile, pulled open the curtain, and went into the bedroom. Tommy heard him staggering about, taking off his clothes, then the creak of the bed and low voices exchanging a few words. After a moment there was silence, nothing but the crackle of the bush outside, that constant rustling, and the faraway howls of dingos hunting in the night. Father began snoring and the silence in the house was broken, and Tommy was grateful that it was. Grateful for the distraction, for his family, for the warmth of the fire on his back.

3

AFTER BREAKFAST TOMMY AND Billy pulled on their boots and came out onto the verandah and found Arthur standing alone with the horses and dogs in the yard. The sun was not long up, the morning still cool, the sky fresh and clean and new. Tommy raised a hand against the glare as he came down the steps, and the old blackfella laughed his rattling laugh and called, ‘Ah, look at em! Like two baby possums just crawled out the nest!’

Tommy had known Arthur all his life. He’d come with Father from Broken Ridge when Father first took on the selection, and these days was part of the family just about: other stockmen came and went but Arthur had always been there. When Tommy was a boy he’d seemed truly ancient, but after all these years he’d hardly aged. He wouldn’t say how old he was, claimed not to know himself. Other times he’d twirl a hand in the air like he was conjuring, then make some outlandish claim. He was a hundred, a thousand, as old as the trees; or he was still only seventeen, or twenty-one, immune to the passage of time.

The dogs ran towards them as the boys crossed the yard. Red and Blue were heelers, a kelpie-dingo cross bred for the scrubs, and excited to be working despite working every day. Tommy scratched Blue’s ear and patted his flank. Red circled Billy impatiently, hoping for the same.

‘Where’s the others at?’ Billy asked Arthur.

‘Sheds,’ he replied, nodding in that direction, flicking tangles of grey hair. The grey had crept into his beard too, but hadn’t taken it yet, the beard a thick black slab reaching down to his chest. He was still smiling, his laughter slow to fade, the skin creased in heavy folds around his nose and eyes. One of his front teeth was missing: Arthur had grown up the old way.

‘Heard you youngfellas got lost yesterday. Best stay close out there, I reckon. Big old place them scrubs. Dangerous country for two lost boys.’

Tommy smirked, but Billy snapped, ‘We was hunting, not lost.’

‘Well,’ Arthur said, sorting through the various sets of reins and offering one to Billy, ‘your old man wants you on Jess anyhow, stop you wandering off.’

Billy scowled at the packhorse, heavily laden with supplies. Feed bags, water bags, lifting ropes, dog muzzles, even the billycan for their tea. Jess had a put-upon expression well suited to her trade, and for all the world seemed to return Billy’s scowl; the horse looked just as unenthusiastic about their pairing as he.

‘Joseph can take her. I’ll ride Annie.’

‘Boss says Joseph’s on Annie today.’

‘Beau, then.’

Arthur began chuckling. He shook his head. ‘Your brother’s on Beau. It’s Jess or nothing for you, except maybe a bloody long walk.’

Tommy mounted up quickly, before Arthur changed his mind. Beau was a dun-grey gelding he preferred over all the rest. Other than Buck, the brumby Father broke and would let no one else ride, the horses were generally shared. But everyone had their favourite, and being the new boy Joseph was usually given Jess. Billy was still complaining as he took hold of her reins, the packhorse standing sullen as a mule. He mounted her roughly. Jess stepped and flicked her head, but Billy brought her around hard and she settled soon enough. She wasn’t the type that needed romancing; small mercies at least.

Arthur mounted up too, and together they sat waiting, until Father and Joseph came out from the store shed, Joseph carrying the last of the supplies. As he secured them onto the pack-saddle, Father stood between Tommy and Billy and held up the flask of strychnine powder for both of them to see.

‘Don’t touch this,’ he said, more to Tommy than Billy, it seemed.

‘I know that,’ Tommy said.

‘Well, I’m telling you again: don’t touch it.’

‘Alright, but I know.’

Father wedged the flask into his saddlebag, buckled the strap, mounted up, and they waited for Joseph to finish loading, all of them watching him, this new man in their little crew. He had short hair, no beard and looked barely out of his teens. Tommy didn’t fully trust him yet, had hardly ever heard him speak. Three months he’d been at Glendale, and he’d barely said a word, not to the family at least. Mother thought him surly, she’d said so more than once, and Father didn’t disagree—he’d only taken him on because Reg Guthrie quit for the diggings and he couldn’t afford another white man’s wage in a drought. Arthur’s opinion had swung it; he’d decided Joseph was alright. That was enough for Father. For all of them, in truth.

Joseph finished packing and mounted up. Father whistled for the dogs and they rode out, heading north and then west, empty country to the horizon and for many miles beyond.

* * *

Mid-morning they found their first carcass. The dogs stopped their weaving through the spinifex and pointed themselves stiffly at the scrub. Steadily the five horses approached, no faster than walking pace in this heat. There was no shade, no respite from the sun, the wind only made it worse. All of them were sweating. Dark stains on their shirt backs, faces glistening beneath the brim of each hat. Joseph had his shirt open, and the sweat stood in beads on the scars that climbed ladderlike up his chest. Tommy couldn’t stop staring at them, couldn’t help but guess what those scars meant. They looked like notches: a tally carved into the skin. The thought chilled him. He counted four scars—did that mean four men? And what about those troopers yesterday? How many must they have had? Were their torsos, their entire bodies, riddled with marks?

Tommy was pulled out of himself by Father swinging down from his horse, handing off his reins to Arthur and walking towards the dogs. Flies hung over the clutch of scrub in a rolling dark cloud, diving and lifting and diving again. The dogs yapped then fell still. The others waited. Wafts of spoiled meat carried on the air. Tommy took off his hat, wiped himself down, swatted the flies. He glanced at Billy, looking miserable on Jess—Tommy knew how her gait would be hurting his backside; there was no pleasure in riding that horse. He offered what was meant as a conciliatory smile. Billy snorted and looked away.

With his sleeve covering his mouth Father leaned over the carcass like a man over a ledge, then came back shaking his head.

‘No good. Maggots are already in there. Must be three days old at least.’

Arthur handed back his reins. ‘Dingos get into her yet?’

‘Aye,’ Father said. He mounted up and took the notebook from his shirt pocket, licked the tip of the pencil and made a mark.

‘Not blackfellas, though?’ Arthur asked him.

‘Nope. Drought. Which is something, I suppose.’

They moved on. Tommy looked at the cow as they passed. She was sprawled on her side in the dirt, hide hacked open, innards dragged out. There were pockmarks in her skin from the eagles and crows, and both eyes were gone. Flies lay upon her like a newly grown pelt; as one they rose when the horses went by, a shadowlike swarm hanging then descending again as soon as the party was clear.

The next carcass was more recent, not yet a day old. Father inspected it then came back and unbuckled the strychnine flask from his saddlebag.

‘You two muzzle the dogs. Joseph, open her up.’

The young stockman frowned at the instruction. Arthur explained, mimicking a blade with his hand, pointing at the cow and the flask Father held. Joseph shook his head. He turned and stared off into the scrub and Arthur reached out and slapped him on the arm, but Joseph didn’t respond.

‘Problem?’ Father asked.

‘Might be,’ Arthur said, glaring at Joseph as he fidgeted on his horse. This wasn’t the first time he’d been like this. Tommy remembered him refusing to shift grain sacks, not long after he was first set on, claimed they were too heavy to lift. There’d been days he’d missed the sun-up, gone off wandering and come back hours later, then whenever Father got into him, Joseph would just stand there and take it, not a word in return, like it was nothing to him, like he didn’t care. He had a long and empty stare that slid right off you, but there was always something brooding in him. Mostly against Father. The two of them had been at odds from the start.

‘Bloody hell, Arthur, will you just tell him.’

Arthur drew his bowie knife and offered it hilt first. Joseph glanced at the knife then away. Arthur said, ‘Well I ain’t bloody doing it, and he’s not gonna ask the boys. So it’s either you or the cow, mate—which’ll it be?’

Joseph chewed on his tongue, then reached out and took the knife. They all dismounted. Joseph threw Father a look as he went by. Father shook his head and went after him, directed where to make the cut. Joseph lifted the hind legs, sawed the carcass sternum to tail; the innards came sluicing out. Joseph stood aside, holding the knife, blood coating his forearms, and Tommy found himself counting the scars on his chest again.

‘Tommy! Wake up, son!’

Father was unscrewing the strychnine. Tommy took a muzzle from Billy, caught hold of Red and pinned him between his knees, wrestled the muzzle on. Red didn’t like it but knew what to expect: both dogs had been with the family since they were pups. Tommy tied the buckle and held Red back, Billy did the same with Blue, all of them upwind of the cow. Father motioned for Joseph to lift the hide, and when he did so Father tipped in the powder then quickly jumped away. Joseph let the belly flap closed, walked back to his horse. Already the flies were gathering—the dingos would soon catch the scent. But strychnine was totally odourless: before they knew what they’d eaten, they’d be dead.

They poisoned two other carcasses as they rode across that featureless scrubland broken only by lonely gum trees or thin pockets of brigalow, all of it drenched in a hard and endless sun. There was a gentle incline to the landscape, sloping down towards the distant creek, and from here they could just about glimpse the ranges in the west, a low dark outline crouched upon the horizon like a storm cloud touching the earth. It was a week’s ride to those ranges, across unsettled country where few men had ever been, no telling what lay beyond. Father had a surveyor’s map showing their selection and the surrounding land, everything to the north, south or east. The lines only went so far west then faded into nothingness; the interior blank, like some vast uncharted sea.

The cattle they found wandering loose needed droving back down to the creek. Father and Arthur mustered them easily, one on each side, their horses positioned just so, walking them slowly forward, everything nice and calm. Tommy was always impressed by how simple it looked, when he knew it was anything but. Small details. Mostly reading the cattle, Father said. The last few years Tommy had been allowed to go out with the men on the main spring muster, but he’d done little more than make the tea and cook. That was how everyone started, Father had told him. That was how you learnt.

Some of the cattle they found simply lying in the scrub, too weak and exhausted to stand. The dogs nipped around them but even then they wouldn’t move: gaunt, with their legs tucked beneath them and tongues lolling, moaning pitifully when the horses came into view, might as well have been waiting to die.

‘She’ll need lifting,’ Father said, when they came across the first. He nodded at Tommy and Billy. ‘On you go then, get her up. Billy’s got the sling.’

They looked at each other. ‘Just us two?’ Tommy asked.

‘Aye, just you two. Or did you reckon I’d forgotten about yesterday?’

‘She’s only a littl’un,’ Arthur said. ‘Doubt she weighs much more than you.’

Arthur was laughing as Tommy climbed down. He’d helped lift cattle before but never done it on his own. He walked around to join Billy, who was unstrapping the harness from his pack, a home-made sling of stained canvass with thin ropes through metal eyelets in each corner of the sheet.

‘You know how to do this?’ Tommy whispered.

‘Course I do. So do you. Come on.’

They spread the sling on the ground beside the cow, Billy at the hindquarters, Tommy at the head, and worked it under her body with the ropes. The cow watched them warily, grumbling and shifting as they dragged the sling through. Tommy stood back panting, but Billy was already passing his end of the harness back over the cow and tying off the ropes to pull it snug. Tommy copied him, glancing up at Father, who stared impassively down.

‘I didn’t ask you to dress her, Tommy. Lift the bloody thing!’

They got a grip on the ropes and began pulling. The cow didn’t so much as flinch. Tommy’s hands slipped on the rope, his palms burned on the weave. Billy was struggling just the same; he wrapped the rope around his forearm, Tommy did likewise, both of them grunting and cursing, their boots sliding backwards in the dirt. And still the cow didn’t move.

Tommy turned his back on her, hooked the rope over his shoulder like a horse pulling a dray. He lost his hat. The sun stung his eyes, sweat soaked his face, his hands were burning and somewhere the dogs were barking, then suddenly Arthur was shouting, ‘Yes, boys! Lift her! Yes!’ and there was movement behind them, the cow inching sideways through the dirt. Tommy glanced over his shoulder and saw her rock herself forward, then the hind legs straightened and she was tottering unsteadily to her feet. He dropped the rope and collapsed. Billy began cheering, Arthur too; even Father smiled. The boys untied the harness and the dogs got into the cow, making sure she kept her feet, and Tommy and Billy came together in a clumsy half-embrace.

‘Alright, that’ll do,’ Father said. ‘Get it rolled and packed away. I doubt we’re done with it yet.’

They all took the ropes for the next one, and three more after that, and by the time they reached the creek they were driving two dozen head back into the main mob. If it could be called a mob: a smattering of moaning cattle strung out across the floodplain, desperately foraging for feed. The grain sacks piled on Jess were emptied in the troughs, but there was only so much grain to go around. Father watched the cattle bitterly. A kind of hatred in his eyes. Blaming them, almost. As if what had become of them was somehow their own fault.

The group took lunch by the creek, in the shade of the red gums that grew along its banks. Salted beef, bread and butter, but it was too hot for tea and there was no sense risking a fire. Bush this dry was like tinder. One spark and it went up.

After they’d eaten they lay on the bank while the horses took a spell, and soon there were sounds of light snoring as one or another slept. Tommy lay looking up at the leaves, listening to the trickling creek and remembering the rains they used to get when he was young. When the flow became a torrent and the whole floodplain drowned—they’d have been six feet underwater, lying on this bank. Miles downstream, there was a waterhole called Wallabys, where the family went in the summertime to bathe. The river fed a waterfall spouting directly from the rock face, and the pool was often deep enough to dive. He wasn’t much of a swimmer, but he’d loved it, the feeling of plunging into that pool, Mother clapping each dive from the side. How many years since they’d been there? When was the last time he swam?

Tommy rolled his head towards Father, sitting along the bank, his notebook open in his lap, staring across the creek. The land on the other side belonged to Sullivan: the creek marked the western boundary of Glendale. Father noticed Tommy watching, closed the notebook, put it away.

‘I’ll bet you’re bushed after all that?’ he asked him.

‘I’m alright,’ Tommy said. ‘Hands are a bit sore.’

‘You did well. I didn’t reckon you’d lift her.’

‘Showed you then, didn’t we?’ Tommy said, smiling. Father smiled too. There was a pause, then Tommy asked him, ‘So how bad is it? How many we lost?’

‘Ah, don’t worry about it. Couple of dozen, that’s all.’

‘Feels like more.’

‘Is that right now?’

‘There’s no grass. How long have they got?’

Father sighed and looked at the creek. ‘They’ve got long enough.’

Billy was lying on Tommy’s other side. He rose onto his elbow and called, ‘I’ll bet John Sullivan’s got plenty fodder. Grass to spare up there.’

‘I’ll bet you’re probably right,’ Father said.

‘So why not ask if we can graze them? Only till the sales come round, and if he wants something for it we’ll pay him out of the take.’

Father snorted bitterly. ‘Like he doesn’t get enough.’

‘Still, it’s better for us than if the whole mob starves.’

‘The answer’s no, Billy.’

‘Can’t hurt at least to ask him.’

‘Yes it can. The answer’s no.’

Father rocked himself forward and groaned as he climbed to his feet. He nudged Arthur and Joseph awake with his boot cap, then went to where the horses were tied in the trees. The group rose wearily, gathered up their things, and followed. As they walked, Tommy leaned close to Billy and whispered, ‘How would you know about Sullivan’s paddocks if we never went past them blue gums?’

Billy shrugged. ‘I’ll say I was only guessing. You saw what he has, though. Imagine the take if we got them fattened up first.’

‘He won’t ask him. You won’t change his mind.’

‘I know. Man’s more stubborn than that bloody packhorse. My arse is on fire, Tommy. I’ll be lucky if I can sit down for a week!’