11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

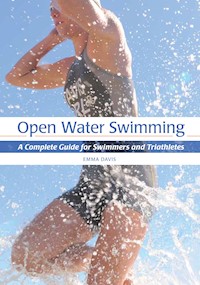

Open Water Swimming: A Complete Guide for Swimmers and Triathletes is aimed at all levels of open water swimmer, from beginners right through to competing professionals. It covers all aspects of the sport: its history and health benefits; a thorough introduction to getting started; a full discussion on training equipment and how it should be used; the safety and legal aspects of choosing a suitable location for swimming; acclimatization for both the beginner and the experienced swimmer. The author then goes on to explain in detail all technical aspects of open water swimming; sighting; drafting; turning around buoys; entraces, exits and transitions. Topics covered include: the importance of nutrition - for training, competition and improving recovery - and injury prevention and rehab, including a programme for core stability and stretching. The only open water swimming guide to be written by a professional athlete and Olympian. Basic training programmes for Triathlon 750m and 1500m distances, Ironman events and 10km and channel swimming. Superbly illustrated with 75 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 156

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Open Water Swimming

A Complete Guide for Swimmers and Triathletes

Open Water Swimming

A Complete Guide for Swimmers and Triathletes

EMMA DAVIS

This e-book first published in 2013 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

© Emma Davis 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 610 9

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

1Introduction to Open Water Swimming

2Equipment and Getting Started

3Open Water Acclimatization

4Situations to Avoid

5Sighting

6Competitive Open Water Swimming

7Swim Drafting

8Starts, Exits and Turning around Buoys

9Nutrition

10Basic Training Programmes

11Possible Injuries and their Management

12Frequently Asked Questions

13The Final Word

Glossary

Further Information

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are many people without whom this book would not have been written, and I would like to take this opportunity to express my thanks to as many of them as possible. First of all, thank you to my amazing friend and photographer Kirsty Nethercott, my swimming and rehabilitation models Matthew Langston and Luke Francis, computer expert Alex Todd for his help with the anatomical body diagrams, to my two very special proof readers, Ann and Phil, who never tired of re-reading, and to all those at Hampton Pool, Open Water Swim and Liquid Leisure.

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION TO OPEN WATER SWIMMING

Quite simply, open water swimming is swimming in open water: that is, swimming outside in lakes, rivers, canals, reservoirs or the sea. For those who are adrenalin junkies, open water swimming can encompass so-called ‘extreme swimming’, the riskiest and potentially the most dangerous form of swimming there is.

The History of Open Water Swimming

Open water swimming as a sport dates back to 1810 when Lord Byron swam from Europe to Asia across the Hellespont, or the Dardanelles as we now call it. At the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 the swimming event was held in open water, but as the participating nations became wealthier and more sophisticated, the number of public swimming pools gradually increased, and so it became customary to swim in a pool. This was mirrored in the events of the Olympic Games, as the open water swimming event was eventually replaced by pool swimming, and the number of events proliferated.

But we have moved full circle, because at the Sydney Olympic Games in the year 2000 the triathlon made its first appearance, an event involving a 1,500m swim in Sydney harbour; and in 2008 at the Beijing Olympic Games, open water swimming was back as a competition in its own right, as a 10km race. The General FINA World Championships now include 5, 10 and 25km open water swims, and open water swimming is currently experiencing a real explosion in both mass participation and performance level competition.

We will now explore some of the reasons why you should follow suit and take up open water swimming.

The Benefits of Open Water Swimming

The most important reason for taking up open water swimming, as with any sport, is for pure enjoyment. The feeling of being suspended is so special: in the water your body feels lighter, more elegant and free – it is a whole other world. In the water most of our senses are greatly restricted – eyesight is blurred, hearing is minimal, and there isn’t anything to smell or taste – and because of this, the one sense that we have left, touch, is heightened. Thus in the water we feel everything to a much greater degree: the way the water pushes back on our hand and arm as we pull ourselves through it; how the hairs on our legs restrict its flow; the splash of it on our face; even the nastiness of it going up our nose. This is one of the few situations where you are able to experience the sense of touch to such an extent.

Swimming indoors is pleasure enough, but why not head outside to nature? No more the boredom of swimming up and down the pool, endlessly counting the number of lengths you have swum; and also no more all the nasty chemicals required to keep the swimming pool fresh and sanitary – you no longer smell of chlorine for days after you swim, the air is fresh and clean, and there is so much to see! Why stare at a black line when you could be following a ghost carp or even swimming alongside a dolphin?

Swimming is also one of the most body-friendly forms of exercise. It is impact free and therefore kind to joints and bones, and is an extremely good source of whole body exercise, facilitating muscular contractions that are neglected during other forms of exercise. Even greater benefits can be experienced in cardiovascular efficiency, joint flexibility and muscular condition. The breathing muscles in particular – the diaphragm, and the outer and intercostal muscles – are targeted, and there is really no other form of exercise that so effectively hits these muscle groups. Consequently swimming is an ideal form of exercise for people with breathing conditions such as recurrent bronchitis or asthma. All in all, the improvements to health and the individual’s quality of life can be felt almost instantaneously.

These bodily changes occur when just swimming in a pool, but when open water swimming we enter into a whole new dimension of the sport and will encounter even greater advantages. We will experience other factors such as currents, waves and the wind, three elements that add to the challenge – the effort feels harder, with the wind and the currents pushing us back and the waves crashing down on us – or we may suddenly come across a buoy we need to navigate around, or a swimmer to avoid or overtake.

At first, all this may seem to be a down side to open water swimming, with hazards and features that we wish weren’t there or that we would prefer to avoid. We may wish we could just flick a switch and turn off the weather or slow down the current, move a buoy a little to the left, and get rid of all those other annoying swimmers – but with experience you will find that these are really the benefits, as they increase the excitement and enhance your workout.

From a health point of view the benefits are substantial, even over indoor swimming. In these tougher weather conditions our stabilizing muscles – the rotator cuff, serratus anterior, levator scapulae and lower trapezius – become more central in the equation: we must change our stroke pattern to go round buoys, and increase the pace to stay with the pack or overtake. All of this varies the challenge to our energy system: it avoids the repetitive strain that can be experienced in pool swimming, but in turn produces the balanced spread of work that we need.

From the perspective of rehabilitation, open water swimming is fantastic. The overuse injuries that swimmers tend to incur are less likely in open water swimmers: the fact that the stroke has to be constantly altered means that the motion is never quite the same so the muscles used are varied, and as a consequence, nothing is overused. Many of the areas that pool swimmers need to work on to ensure their musculature remains balanced (thus minimizing the risk of injury) are being taken care of whilst training specific areas – and at the same time, we are tapping into aspects of physiology that are difficult to access with other activi-ties.

Now is the time to get started, so dive in!

CHAPTER 2

EQUIPMENT AND GETTING STARTED

One of the great things about swimming as a hobby or sport – and open water swimming is no exception to this – is that you don’t need to invest large sums of money in sophisticated kit before you can take up the sport. Furthermore everything you need to enjoy your sport can be packed into and carried in a small holdall, so you can be much more flexible and spontaneous than some other popular sports such as golf, skiing or sailing, for example. Essentially all you need to start open water swimming is yourself, a stretch of water, and the will to get in and give it a go. However, in practice there are a few things that can be of help and will make the experience more pleasant.

Basic Equipment

Swimming Costume

First on your list should be a swimming costume. Although there are a few stretches of water where ‘skinny dipping’ is permissible, they are few and far between in the UK. This needn’t be anything fancy, just something to keep your modesty. It is possible to purchase extremely expensive costumes, which claim to do all sorts of things with the aim of making you faster in the water. They do succeed in this, as can be seen in the swimsuit regulation debacle of 2008–10, when suits such as the speedo LZR racer and Blue Seventy Nero Comp were released on to the market at the beginning of 2008. These suits work in different ways to increase a swimmer’s buoyancy, the LZR suit compressing the muscles and trapping air, whereas the Nero Comp is made of special material similar to that of a wetsuit: the higher you are in the water the less resistance you create, which means you will swim faster. In 2010, FINA – the international governing body of swimming, diving, water polo, synchronized swimming and open water swimming – banned certain swimsuits from FINA-approved events, stating:

FINA wishes to recall the main and core principle that swimming is a sport essentially based on the physical performance of the athlete.

Just as car racing is often considered nowadays to be more about the car and less about who is driving it, these suits were deemed to give such an advantage that swimming was becoming more about technology than athleticism. Records were being broken everywhere, and by a degree that had never been seen before in the history of swimming. The new FINA rules state that:

•Male swimsuits should only cover the area from the waist to the knee and women’s counterparts the shoulder to the knee

•Suits must be of a ‘textile’ or woven material (although what they mean by ‘textile’ was not qualified)

•They must not have any fastening devices such as zippers (although drawstrings are allowed)

These regulations are only for FINA-approved events and thus will only affect open water swimmers competing under the auspices of that organization. In some triathlon or non FINA-approved open water swimming events, a swimskin may be allowed when a wetsuit is not: these are similar to wetsuits but not as thick, and thus not as buoyant. However, they will give you an advantage over those wearing just a regular swimsuit.

If you enjoy acquiring the latest, fanciest bit of kit for your hobby and can afford it, then you can consider buying the latest race-legal suit you can find. However, this expenditure is really not necessary in order for you to take up open water swimming – just as you don’t have to buy a Ferrari in order to start driving. Unless you are competing at the highest level, such a purchase would be simply an indulgence.

Goggles

A good pair of goggles is essential. Everyone has a differently shaped face, and thus a pair that fits one swimmer will not necessarily fit another. A good test is to push the goggles gently into your eye sockets and see if they stick: if they remain in place for a few seconds, then it is likely that you have found a good match for your face shape.

When goggles are brand new they have a layer of anti-fog solution on the inner side of the lens, but over time and with use this wears off, and your goggles may start to fog up as you are swimming. This will be more noticeable when swimming in cold water. When this starts to happen it doesn’t mean that you must immediately purchase a new pair, as it is possible to defog your goggles to prolong their life. There are specific anti-fog solutions applied direct to the lenses that are commercially available, or there are a couple of cheaper options that work well. The first, and a good alternative to the more expensive, commercially available products, is to coat the inner side of the lenses in toothpaste or washing-up liquid, and then wash them out – but be sure to rinse the lenses thoroughly before wearing them, as you don’t want an eyeful of either substance!

The other alternative is cheaper still – in fact it is completely free! Simply spit into the lenses of your goggles, rub the spittle around, and then rinse them out just before you enter the water.

PUTTING ON HAT AND GOGGLES

It is wise to wear your goggles under your swimming hat, as this protects them from being knocked off by another swimmer in crowded conditions. So, first place your goggle lenses on to your eye sockets, and then pull the strap over your head. Most goggles have a double strap at the back, which can be spread out on your head to ensure a sturdy hold. If you have long hair, tie this up into a ponytail first, and secure one strap above the ponytail and one below. Then put your hat on over the goggles. The seam down the middle of the hat should go down the middle of your head from front to back.

If you find that your goggles are continually slipping, wear two hats, one under your goggles and one over them.

Hats

It is advisable to wear a swimming hat in open water unless the water temperature is very hot, in which case swimming without a hat can help to cool your core temperature.

A silicon hat is a more comfortable option than a latex cap, which may pull at your hair. Cotton hats can also be used and are good in hot conditions as they will allow heat to escape from your head more efficiently, and thus lower your core temperature. For speed, however, silicon tends to be the first choice – and furthermore silicon hats will last longer than latex hats if taken care of properly: they should be washed out with fresh water each time after wearing, and left to dry at room temperature in a shady spot.

Wetsuits

Most open water swimmers will need a wetsuit. There are plenty available at greatly varying prices, and if you do want to indulge your craving to spend, here is where to put your cash.

Wetsuit fit is extremely important, and you should always try before you buy. Most wetsuit manufacturers nowadays will allow you to try a ‘demo’ wetsuit actually in the water before you buy, so do this if at all possible. If you cannot find anywhere that allows this, at least try on the wetsuit on dry land, and do a few arm swings or strokes to see how it fits.

Use the manufacturer’s size guide to pick out a suit that you think will be a good fit. Then with the zip at the back, pull the legs of the wetsuit up your legs as you would pull on a pair of tights or leggings: the crotch must be pulled up snuggly into your crotch and all the wrinkles smoothed out. Now do the same with the arms, ensuring that they are pulled up securely all the way into your armpits. It is important to pull the crotch and armpits of the wetsuit all the way up, because if you don’t, when you attempt to swim your muscles will have to work harder to overcome the resistance of the wetsuit.

Finally do up the zip; if possible, ask a friend to do this for you, as they can smooth out the zip lining and make sure that it remains smooth as they do it up. As shown in the photos, with ‘normal’ zips, pull the zip-pull over the top of the neck flap, and then pull the neck flap firmly, but not too tightly, across, ensuring that the male and female parts of the velcro are pushed together. With reverse zips the zip-pull can hang down loosely, though in some suits there is a small spot of velcro to which to attach it.

Apply Vaseline or some such lubricant on the back of your neck to help prevent chaffing, and you are ready to go.

The Right Size

So how do you know if you have the right size? It is normal that the wetsuit will feel restrictive and tight on land and to an extent in water, so do not decide on a suit simply because it feels comfortable on first wearing. Things to look out for that indicate a suit is too large for you include water entering at the neck or arms, or water pooling in your lower back. This is why it is preferable to try out the suit in water before you decide whether to buy.

On the other hand, if you feel your breathing is restricted because the wetsuit is tight across your chest, this would indicate that it is too small.

Remember, a wetsuit will stretch a little with wear, but it will never shrink or pull back into shape, so err on the side of too tight rather than too slack. However, if you are not satisfied with the fit, don’t be afraid to try another manufacturer because, just like everyday clothes, all makes fit slightly differently.

Fig. 2.1a–gEnsure the wetsuit is pulled fully up to your crotch.

Make surehat you pull the arms right up to your armpits.

With the zip-close flat, pull the zip up and close the velcro over the zip-pull.

Where Can I Swim?