Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Dylan Thomas is one of most beloved poets of the twentieth century. Richly melodious and expressive, Thomas's poems strike to the heart of eternal themes of living and dying, of childhood days lost and the vigorous beauty of nature. With restless creativity, he made the English language anew and his work inspired countless artists from Igor Stravinsky to Bob Dylan.In this new selection, Cerys Matthews brings together poems from across Thomas's career - including some of his very earliest works - to showcase the blossoming of his singular poetic voice. Full of lush imagery and unforgettable lines, this is the perfect introduction to a remarkable writer.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

‘His poetry leaves echoes in the mind as music does, as all true poetry should… The whole man, body and mind, and the whole life are in the words. We see ourselves on the page, feel the arrow in the heart’

GUARDIAN2

3

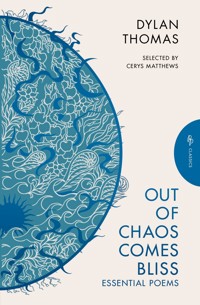

OUT OF CHAOS COMES BLISS

DYLAN THOMAS

SELECTED AND INTRODUCED BY CERYS MATTHEWS

PUSHKIN PRESS CLASSICS

Contents

Introduction

I’d be a damn fool if I didn’t!

I read somewhere of a shepherd who, when asked why he made, from within fairy rings, ritual observances to the moon to protect his flocks, replied: ‘I’d be a damn fool if I didn’t!’ These poems, with all their crudities, doubts, and confusions, are written for the love of Man and in praise of God, and I’d be a damn fool if they weren’t

(DT, November 1952, in a Note to his Collected Poems)

And ‘I’d be a damn fool if I didn’t!’ pretty much summed up my reaction when Pushkin Press asked me to pull this book together. Worm into the apple of his works and bring up a new collection—for the suns of 2024? YES! With bells on.

Enter another quote from DT (throughout, as you’ve probably guessed, Dylan Thomas will be referred to as DT) to offer up my freewheeling selection process:

Read the poems you like reading. Don’t bother whether they’re important, or if they’ll live. What does it matter what poetry is, after all? If you want the definition of poetry, say poetry IS what makes me laugh, or cry or yawn, what 10makes my toenails twinkle, what makes me do this or that or nothing and let it go with that.

(DT, in response to a question asked by a University of Texas student in 1950)

So here we have them, poems which make toenails twinkle, make you laugh or cry, which sing the loudest, have the most unforgettable imagery, lines, the best stories, are most revealing about the world then or now—or about the man, and boy, who held the pen.

Many of these poems were written by DT while he was still a teenager. I was curious to see just how early you can trace this precociousness. With excitement, I include several examples of ‘unpublishable’ juvenilia never before published together, including his first nationally published poems, first for Wales only, and then his first issued UK-wide.

For further interest about his family and the early years, here is an extract of a conversation between my uncle Colin Edwards and DT’s mother Florence in 1958:

‘He must have been a very bright child.’

‘Oh, he was. And then, whenever it was wet or anything, you had no trouble in entertaining him. Give him plenty of notepaper or pencils, he’d go into his own little bedroom and write and write and write. And reams of poems.’

‘At what age did this start?’

‘Oh, he started about eight, I should think. And he’d ask his sister, Nancy, sometimes, “What shall I write about now?”

11And you know what sisters are, they’re not very patient with their brothers, and she’d say, “Oh, write about the kitchen sink!” He wrote a poem, a most interesting little poem, about the kitchen sink. Then about an onion.’

(From Dylan Remembered: Vol I, 1914–1934, ed. David N. Thomas)

You’ll find more from this conversation, as well as other quotes and notes about the poems, at the back of this book, though I’m not sure DT would approve of these, either: he was the one who called the juvenilia ‘unpublishable’.

He would most probably rather we let the poems talk for themselves, and for us to take them literally, draw a breath and jump in with

‘i am going to read aloud.’

And off you’d go reading.

But that’s him, and this is my tribute to him, and he’s not here, alas, to fight. Besides, I’d like to imagine that he’d rather enjoy the ride in a way. As for the endnotes, I’ve included quotes from DT regarding specific poems as often as I thought worked.

Now, back to the reciting:

Then the man rose and rhythmically swaying on the ball of his feet… he let loose the wanton power of his voice… It made us yield to his spell… words were full of witchery.

(Professor Cecil Price, head of English at Swansea University, who invited DT to speak to students in April 1951)

12I don’t remember quite when I was bedevilled by his words. I grew up with the same view of the crescent-shaped bay in Swansea, but we never studied DT’s writing at school.

My uncle Colin, mentioned above, amassed hundreds of hours of taped interviews in the 1950s and 1960s with DT’s closest family, friends and associates (grist to the mill for many a subsequent book and article by academics), but I was too young or foolish to make the most of that connection.

It wasn’t until I was away from Wales, in South Carolina, pregnant with my first child, when I happened on a tiny tree-ornament book of DT’s, A Child’s Christmas in Wales (first published 1950):

‘Our snow was not only shaken from whitewash buckets down the sky, it came shawling out of the ground and swam and drifted out of the arms and hands and bodies of the trees; snow grew overnight on the roofs of the houses like a pure and grandfather moss, minutely ivied the walls and settled on the postman, opening the gate, like a dumb, numb thunderstorm of white, torn Christmas cards.’

‘Were there postmen then, too?’

‘With sprinkling eyes and wind-cherried noses, on spread, frozen feet they crunched up to the doors and mittened on them manfully. But all that the children could hear was a ringing of bells.’

‘You mean that the postman went rat-a-tat-tat and the doors rang?’

‘I mean that the bells the children could hear were inside them.’

13I was smitten, the tender writing seen above, the humour, heart and cheek—lines like ‘Ernie Jenkins, he loves fires’, ‘an aunt now, alas, no longer whinnying with us’, and scenes of chaos played out in homes across Christmas:

Auntie Bessie, who had already been frightened, twice, by a clock-work mouse, whimpered at the sideboard and had some elderberry wine. The dog was sick. Auntie Dosie had to have three aspirins, but Auntie Hannah, who liked port, stood in the middle of the snowbound back yard, singing like a big-bosomed thrush.

Roll on twenty years and DT has become a massive part of my life—I’ve got a musical of A Child’s Christmas running in Minneapolis for its second year, an illustrated children’s edition of Under Milk Wood (1954) with artist Kate Evans, a ballet choreographed around his poems and I have written and presented many documentaries with DT at their heart.

But let’s go back to him then, and Professor Cecil Price again: ‘His poetry was an incantation, a charm to rob evil and good of their influences and leave us all naked things of sense.’ Which means job done for DT. Here he is answering the question ‘Have you been influenced by Freud and how do you regard him?’:

Yes. Whatever is hidden should be made naked. To be stripped of darkness is to be clean, to strip of darkness is to make clean. Poetry, recording the stripping of the individual darkness, must inevitably cast light upon what has 14been hidden for too long, and by so doing, make clean the naked exposure

(From ‘Answers to an Enquiry’, first published in New Verse, 11th October 1934)

But why did DT start writing poetry in the first place? Again, here he is:

I should say I wanted to write poetry in the beginning because I had fallen in love with words. The first poems I knew were nursery rhymes, and before I could read them for myself I had come to love just the words of them, the words alone… There they were, seemingly lifeless, made only of black and white, but out of them, out of their own being, came love and terror and pity and pain and wonder and all the other vague abstractions that make our ephemeral lives dangerous, great, and bearable.

(From ‘Poetic Manifesto’, first published in Texas Quarterly, 1961)

Let me take you back to 2009. I’m now in one of the front-row terraced houses that line the Mumbles Road with Gwen Watkins, writer and widow of poet Vernon Watkins and DT’s friend, who was telling me about this very thing: the young Dylan was in love with the sounds of words, especially ‘Ride a cock-horse to Banbury Cross’. Remember it? It goes like this:

Ride a cock-horse to Banbury Cross,

To see a fine lady upon a white horse;

15Rings on her fingers and bells on her toes,

And she shall have music wherever she goes.

That line—‘And she shall have music wherever she goes’—could well be describing DT’s wordplay: he took the English language and made it sing.

It’s now 2023, I’m mildly hungover on a very wet August Saturday and reading in the window, watching the River Thames:

Under the mile off moon we trembled listening

To the sea sound flowing like blood from the loud wound

And when the salt sheet broke in a storm of singing

The voices of all the drowned swam on the wind.

(From ‘Lie still, sleep becalmed’)

As in the song ‘Wichita Lineman’, we hear Dylan Thomas humming through the lines… singing in the wires.

We’re here with him now—the sounds he conjures—and I am taken back to chapel, where we’d go three times on a Sunday, bathed by the warm heart of hymns—seducing—and bookended with more storytelling, this time from the pulpit, and another familiar sound, the dynamics and drama, ebb and flow of a sermon.

On he goes in ‘Lie still, sleep becalmed’:

We heard the sea sound sing, we saw the salt sheet tell.

Lie still, sleep becalmed, hide the mouth in the throat,

Or we shall obey, and ride with you through the drowned.

16The world of Dylan Thomas is a giving one. Once you connect with his writing, be it from a play, an essay, story or poem, his words never leave you. Favourite lines or images find homes in the nooks and crannies of your mind, and, once in a while, pop out:

‘What’ll the neighbours…?’

‘Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

‘Fishingboatbobbing sea’

‘Do not go gentle’

‘And death shall have no dominion’

‘Books that told me everything about the wasp, except why’

‘Got off the bus, and forgot to get on again’

‘Yes, Mog, Yes’

And the line which gave this book its title—‘out of the chaos would come bliss’—from his poem ‘Being but men, we walked into the trees’.

Like every great artist, his style reads as effortless, though he often acknowledged the labour behind the magic:

What I like to do is to treat words as a craftsman does his wood or stone or what-have-you, to hew, carve, mould, coil, polish and plane them into patterns, sequences, sculptures, fugues of sound expressing some lyrical impulse, some spiritual doubt or conviction, some dimly realised truth I must try to reach and realise.

(‘Poetic Manifesto’)

17His delight in the malleability and sound of language, his understanding across both Welsh* and English, and knowledge of Auden, Donne, Joyce, Blake, Keats, Shakespeare, Wilfred Owen, among others, come together and make his work striking and original.

He’d have been familiar with the Welsh-language Bible, Welsh-language chapel services (he too went three times on a Sunday) and also the Mabinogion, a collection of stories passed on orally then written down in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. These were presented in Middle Welsh—largely understandable to the modern Welsh speaker. Dylan was even named after one of the characters, Dylan ail Don (Dylan, second wave) from ‘Math fab Mathonwy’.

On this note, the name was used very rarely—hard to imagine now, it being so popular across the Atlantic too, in whichever spelling…

Another note to add: Dylan, in Thomas’s case, must rhyme with villain, according to his mam, Florrie. This is not the conventional Welsh way: conventionally Dylan would sound like Dull-Anne, with emphasis on the dull.

Back to my book, which I hope you’re not finding dull so far. Why am I presenting this in 2024? And why poetry? Again I turn to DT to see what he says on the matter; did he intend his poetry to be useful?

18My poetry is, or should be, useful to me for one reason: it is the record of my individual struggle from darkness towards some measure of light… My poetry is, or should be, useful to others for its individual recording of that same struggle with which they are necessarily acquainted.

(‘Answers to an Enquiry’)

Here’s DT again, from his essay ‘On Poetry’ in Quite Early One Morning (1945):

A good poem is a contribution to reality. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. A good poem helps to change the shape and significance of the universe, helps to extend everyone’s knowledge of himself and the world around him.

With these lofty ambitions in mind, this is probably a good place and time to end my ramblings and instead let me welcome the poems themselves to take centre stage.

I hope you enjoy.

I hope too that you’ll find the magic in them there syllables…

cerys matthews

* Although there’s no recording of DT speaking Welsh, there’s no way he didn’t understand it. Back in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s it would have been the predominant language used by the farming communities of Carmarthen and West Wales, where he spent so much of his childhood. More on that in the endnotes.

(VERY) EARLY POEMS

20

The Song of the Mischievous Dog

There are many who say that a dog has its day,

And a cat has a number of lives;

There are others who think that a lobster is pink,

And that bees never work in their hives.

There are fewer, of course, who insist that a horse

Has a horn and two humps on its head,

And a fellow who jests that a mare can build nests

Is as rare as a donkey that’s red.

Yet in spite of all this, I have moments of bliss,

For I cherish a passion for bones,

And though doubtful of biscuit, I’m willing to risk it,

And love to chase rabbits and stones.

But my greatest delight is to take a good bite

At a calf that is plump and delicious;

And if I indulge in a bite at a bulge,

Let’s hope you won’t think me too vicious.

‘The Second Best’

You ask me for a toast to-night

In this familiar hall,

Where well-known objects greet the sight,

And boyhood’s days recall.

‘Some honoured name,’ I think you said,

But what have I to say?

The King, the Services, the Head,