Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arc Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: Visible Poets

- Sprache: Englisch

Peatlands is the first bilingual single collection of Mexican poet Pedro Serrano's work to be published in the UK. Introduced by WN Herbert, the poems are as linguistically thrilling as they are wide-ranging: with subjects as diverse as snakes and swallows, valleys and skyscrapers, weariness and love. This book is also available as a eBook. Buy it from Amazon here. Pedro Serrano is the author of six poetry collections published between 1986 and 2009. He also co-edited the 2000 anthology The Lamb Generation, which brought together translations of 30 contemporary British poets. His poems have appeared in the likes of MPT, The Rialto and Verse, and in 2007 he was awarded a Guggenheim Poetry Fellowship. He lives in Mexico City. Anna Crowe's other translations include Joan Margarit's collections Tugs in the Fog (2006; ISBN 9781852247515) and Strangely Happy (2011; ISBN 9781852248932), both published by Bloodaxe, and the Arc anthology Six Catalan Poets (2013; ISBN 9781906570606). She lives in St Andrews.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 88

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by Arc Publications,

Nanholme Mill, Shaw Wood Road

Todmorden OL14 6DA, UK

www.arcpublications.co.uk

Original poems copyright © Pedro Serrano 2014

Translation copyright © Anna Crowe 2014

Introduction copyright © W. N. Herbert 2014

Copyright in the present edition © Arc Publications 2014

978 1906570 85 9 (pbk)

978 1906570 86 6 (hbk)

978 1908376 81 7 (ebk)

Design by Tony Ward

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The publishers are grateful to the editors of the following magazines in which these translated poems have appeared: ‘Schoolchildren on Via Augusta’ and ‘Port’, The Rialto (Spring 2009); ‘Rodin’s Garden’, ‘Swallows’ and ‘The Cove at Aiguafreda’, Boulevard Magenta (Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2009, issue 4); ‘Swallows’ Modern Poetry in Translation (Third series, no. 10); ‘Feet’, ‘Snake’, ‘Inside the Chapel’, ‘Lustral’, ‘Swallows’ and ‘Regent’s Canal’, Mexican Poetry Today, 30 Voices ed. Brandel France de Bravo (2010).

A separate translation of ‘Three Lunatic Songs’ was published in a partiuta edition by the Mexican composer Hilda Paredes. The music is for counter-tenor and string quartet, and was first performed at the Wigmore Hall, London, and in Paris, in 2011.

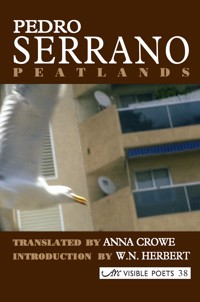

Cover photograph: © Pia Elizondo, 2014, by kind permission of the photographer

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part of this book may take place without the written permission of Arc Publications.

Esta publicación fue realizada con el estímulo del Programa de Apoyo a la Traducción (PROTRAD) dependiente de instituciones culturales mexicanas.

This publication was made possible with the help of the Translation Support Program (PROTRAD), under the auspices of Mexican cultural institutions.

Arc Publications ‘Visible Poets’ series

Series Editor: Jean Boase-Beier

Pedro Serrano

PEATLANDS

Translated by

Anna Crowe Introduced by

W. N. Herbert

2014

CONTENTS

Series Editor’s Note

Translator’s Preface

Introduction

del / from

EL MIEDO / FEAR

Dibujo de las cosas

•

Sketch of Things

El agua que bebemos

•

The Water That We Drink

La lluvia seca

•

Dry Rain

Reconstrucción

•

Rebuilding

Desecación

•

Desiccation

El sol en ascuas

•

The Sun on Live Coals

La fuerza

•

Strength

de / from

IGNORANCIA / IGNORANCE

La sirena

•

The Mermaid

La vendedora

•

Saleswoman

La condena

•

The Sentence

Las hojas, segunda estancia

•

Leaves, Second Dwelling

Tres canciones lunáticas

•

Three Lunatic Songs

Confianza del viento

•

The Wind’s Trust

de / from

TURBA / PEAT

“No hay posesión…”

•

“There is no ownership…”

“Todo se apelotona…”

•

“Everything coagulates…”

“El dolor de los dientes…”

•

“Toothache…”

“Cae el saco oscuro de avispas…”

•

“Dark with wasps…”

“Una brújula azul…”

•

“A blue compass-needle…”

“Lo que tengo es la pluma…”

•

“What I have is the pen…”

“Este es el punto ciego del agua…”

•

“This is water’s blind spot…”

“Como un caracol sordo…”

•

“Like a deaf snail…”

“Contra sí mismo el cuerpo se revuelve…”

•

“The body turns round upon itself…”

de / from

NUECES / KERNELS

Tuscania

•

Tuscania

Puerto

•

Port

Tormenta en Tollington Way

•

Storm on Tollington Way

Colebrook Row

•

Colebrook Row

Regent’s Canal

•

Regent’s Canal

Revólver

•

Revolver

Serpiente

•

Snake

El escriba

•

The Scribe

El arte de fecar

•

The Liminating Art

Rosario

•

Rosary

Lustral

•

Lustral

Desplazamiento de la copa

•

The Glass Displaced

Los pies

•

Feet

Acotamiento

•

Drawing the Boundary

de / from

RONDA DEL MIG / RONDA DEL MIG

Golondrinas

•

Swallows

Jardín de Rodín

•

Rodin’s Garden

Escolares en Vía Augusta

•

Schoolchildren on Vía Augusta

Cala de Aiguafreda

•

The Cove at Aiguafreda

En capilla

•

Inside the Chapel

Biographical Notes

SERIES EDITOR’S NOTE

The ‘Visible Poets’ series was established in 2000, and set out to challenge the view that translated poetry could or should be read without regard to the process of translation it had undergone. Since then, things have moved on. Today there is more translated poetry available and more debate on its nature, its status, and its relation to its original. We know that translated poetry is neither English poetry that has mysteriously arisen from a hidden foreign source, nor is it foreign poetry that has silently rewritten itself in English. We are more aware that translation lies at the heart of all our cultural exchange; without it, we must remain artistically and intellectually insular.

One of the aims of the series was, and still is, to enrich our poetry with the very best work that has appeared elsewhere in the world. And the poetry-reading public is now more aware than it was at the start of this century that translation cannot simply be done by anyone with two languages. The translation of poetry is a creative act, and translated poetry stands or falls on the strength of the poet-translator’s art. For this reason ‘Visible Poets’ publishes only the work of the best translators, and gives each of them space, in a Preface, to talk about the trials and pleasures of their work.

From the start, ‘Visible Poets’ books have been bilingual. Many readers will not speak the languages of the original poetry but they, too, are invited to compare the look and shape of the English poems with the originals. Those who can are encouraged to read both. Translation and original are presented side-by-side because translations do not displace the originals; they shed new light on them and are in turn themselves illuminated by the presence of their source poems. By drawing the readers’ attention to the act of translation itself, it is the aim of these books to make the work of both the original poets and their translators more visible.

Jean Boase-Beier

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

When Pedro Serrano was invited to read his work at StAnza, Scotland’s International Poetry Festival, in 2005, I had the task of providing English translations of about ten of his poems. Many of these were taken from his most recent but unpublished collection, Ronda del Mig (this is the name of a circular road that runs round the centre of Barcelona – Serrano had been invited to teach for a few years at one of the city’s universities). Working on this handful of poems, I was struck both by the lyricism and complexity of the language, and the compelling quality of the voice which was like nothing I had ever read before: they were humane, rich and mysterious poems and I knew then that I wanted to try to translate much more of his work so that English readers could come to know and appreciate it. Pedro sent me a copy of Desplazamientos (Candaya, Barcelona 2006) – the volume of selected poems which draws on all the collections, published and unpublished, after 1986. I knew that it would be a challenge. I am not of that school of translators that seek to hitch a ride on the original and create something quite different of their own making. I believe in staying as close as possible to the voice and spirit of the orginal, listening for a tone of voice, being alert to nuances and ambiguities, to the echoes that float up from other places, listening to the poem as a piece of music, as well as a complex weaving of thoughts and images. Fortunately, English is a language rich in synonyms, with a Latinate voice and an Anglo-Saxon voice, and well-able to match the mellifluous qualities of Spanish.

I think that what the reader of Pedro Serrano’s poetry first becomes aware of is a most amazing eye at work: each poem unfolds through a highly-focused, loving attention, in language that is both precise and ardent, whether the subject is the moon, a dingy London canal, the human body, love-making, feet, stones on a beach, an Italian landscape, or the movement of small children coming out of school. The image of the gaze is central to his work, the gaze but also the sense of touch. For him, days are like windows, and in his later poetry, his passionate gaze observes and often touches the natural world of snake, swallow, lizard, snail, valleys and skyscapes, trees and dung-beetles. In ‘The Water That We Drink’, from Fear, the poet’s gaze embraces his family after the death of his sister – a loving gaze that is both calm and concerned, that looks and does not judge, assuaging fear and providing an acceptance of things as they are. His poetry faces up to chaos and accepts it, searching with the exile’s longing for the origin of things, the place where objects, bodies and words come together. In his poems, Serrano often links objects subliminally through a succession of vowel sounds, and in these translations I have sought to replicate this.

Likewise from Fear, ‘Dry Rain’ finds chaos even in the act of creation: this is a courageous poem about the desolation of spirit that the act of creation – in this case writing – brings. Its opening lines admit that

At times the poem is a collapse,

a slow and painful landslide,

a dark and scandalous rockfall.

I have tried to reproduce the poet’s patterns of assonance in the Spanish with patterns of my own in English, in this case with a series of short ‘a’ sounds, as in ‘bat’. Writers among us will feel the truth of his description of writing, and feel the force of his imagery: the poet continues by observing that the act of creation, for all its pain and chaos, provides its own healing: “The poem writes itself like a scab” he goes on, and it is precisely in “the striations of soil, / the landmarks and overturned plants, / the fractured dryness in the after-silence,” that the poem writes itself. Another poem that is, I think, central to Serrano’s poetics is ‘The Scribe’ and comes from his collection, Nueces, which we might translate as ‘Kernels’. It opens with a familiar Serranian trope, the image of a man at a window, and I find this a most moving poem, in which we catch the poet surprising himself with how modest and even despised memories can be transformed into something remarkable and beautiful:

Out there the countryside of his childhood shines,

a cradle song, some joke or other.

The evening is red and slow,

his memory is nothing but literary.

And it is out of the débris of childhood – “his old junk, his shadows” – with their “toilsome couplings and painful twists”, but also their “quiet toughness and their cunning”, that the poet is able to “inherit songs and feathers and biscuits and socks” and make

… from this pain…