Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ozymandias Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

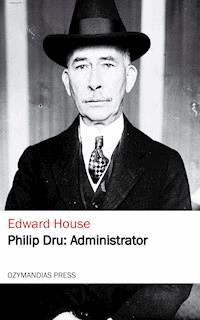

Philip Dru leads the democratic western United States in a civil war against the plutocratic East, and becomes the acclaimed leader of the country until he steps down, having restored justice and democracy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 285

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PHILIP DRU: ADMINISTRATOR

Edward House

OZYMANDIAS PRESS

Thank you for reading. If you enjoy this book, please leave a review.

All rights reserved. Aside from brief quotations for media coverage and reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form without the author’s permission. Thank you for supporting authors and a diverse, creative culture by purchasing this book and complying with copyright laws.

Copyright © 2016 by Edward House

Published by Ozymandias Press

Interior design by Pronoun

Edited by Ozymandias Press

Distribution by Pronoun

ISBN: 9781531279332

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Graduation Day

The Vision of Philip Dru

Lost in the Desert

The Supremacy of Mind

The Tragedy of the Turners

The Prophet of a New Day

The Winning of a Medal

The Story of the Levinskys

Philip Begins a New Career

Gloria Decides to Proselyte the Rich

Selwyn Plots with Thor

Selwyn Seeks a Candidate

Dru and Selwyn Meet

The Making of a President

The Exultant Conspirators

The Exposure

Selwyn and Thor Defend Themselves

Gloria’s Work Bears Fruit

War Clouds Hover

Civil War Begins

Upon the Eve of Battle

The Battle of Elma

Elma’s Aftermath

Uncrowned Heroes

The Administrator of the Republic

Dru Outlines His Intentions

A New Era at Washington

An International Crisis

The Reform of the Judiciary

A New Code of Laws

The Question of Taxation

A Federal Incorporation Act

The Railroad Problem

Selwyn’s Story

Selwyn’s Story, Continued

Selwyn’s Story, Continued

The Cotton Corner

Universal Suffrage

A Negative Government

A Departure in Battleships

The New National Constitution

New State Constitutions

The Rule of the Bosses

One Cause of the High Cost of Living

Burial Reform

The Wise Disposition of a Fortune

The Wise Disposition of a Fortune, Continued

An International Coalition

Uneven Odds

The Broadening of the Monroe Doctrine

The Battle of La Tuna

The Unity of the Northern Half of the Western Hemisphere Under the New Republic

The Effacement of Philip Dru

What Co-Partnership Can Do

GRADUATION DAY

IN THE YEAR 1920, THE student and the statesman saw many indications that the social, financial and industrial troubles that had vexed the United States of America for so long a time were about to culminate in civil war.

Wealth had grown so strong, that the few were about to strangle the many, and among the great masses of the people, there was sullen and rebellious discontent.

The laborer in the cities, the producer on the farm, the merchant, the professional man and all save organized capital and its satellites, saw a gloomy and hopeless future.

With these conditions prevailing, the graduation exercises of the class of 1920 of the National Military Academy at West Point, held for many a foreboding promise of momentous changes, but the 12th of June found the usual gay scene at the great institution overlooking the Hudson. The President of the Republic, his Secretary of War and many other distinguished guests were there to do honor to the occasion, together with friends, relatives and admirers of the young men who were being sent out to the ultimate leadership of the Nation’s Army. The scene had all the usual charm of West Point graduations, and the usual intoxicating atmosphere of military display.

There was among the young graduating soldiers one who seemed depressed and out of touch with the triumphant blare of militarism, for he alone of his fellow classmen had there no kith nor kin to bid him God-speed in his new career.

Standing apart under the broad shadow of an oak, he looked out over long stretches of forest and river, but what he saw was his home in distant Kentucky—the old farmhouse that the sun and the rain and the lichens had softened into a mottled gray. He saw the gleaming brook that wound its way through the tangle of orchard and garden, and parted the distant blue-grass meadow.

He saw his aged mother sitting under the honeysuckle trellis, book in hand, but thinking, he knew, of him. And then there was the perfume of the flowers, the droning of the bees in the warm sweet air and the drowsy hound at his father’s feet.

But this was not all the young man saw, for Philip Dru, in spite of his military training, was a close student of the affairs of his country, and he saw that which raised grave doubts in his mind as to the outcome of his career. He saw many of the civil institutions of his country debased by the power of wealth under the thin guise of the constitutional protection of property. He saw the Army which he had sworn to serve faithfully becoming prostituted by this same power, and used at times for purposes of intimidation and petty conquests where the interests of wealth were at stake. He saw the great city where luxury, dominant and defiant, existed largely by grace of exploitation—exploitation of men, women and children.

The young man’s eyes had become bright and hard, when his day-dream was interrupted, and he was looking into the gray-blue eyes of Gloria Strawn—the one whose lot he had been comparing to that of her sisters in the city, in the mills, the sweatshops, the big stores, and the streets. He had met her for the first time a few hours before, when his friend and classmate, Jack Strawn, had presented him to his sister. No comrade knew Dru better than Strawn, and no one admired him so much. Therefore, Gloria, ever seeking a closer contact with life, had come to West Point eager to meet the lithe young Kentuckian, and to measure him by the other men of her acquaintance.

She was disappointed in his appearance, for she had fancied him almost god-like in both size and beauty, and she saw a man of medium height, slender but toughly knit, and with a strong, but homely face. When he smiled and spoke she forgot her disappointment, and her interest revived, for her sharp city sense caught the trail of a new experience.

To Philip Dru, whose thought of and experience with women was almost nothing, so engrossed had he been in his studies, military and economic, Gloria seemed little more than a child. And yet her frank glance of appraisal when he had been introduced to her, and her easy though somewhat languid conversation on the affairs of the commencement, perplexed and slightly annoyed him. He even felt some embarrassment in her presence.

Child though he knew her to be, he hesitated whether he should call her by her given name, and was taken aback when she smilingly thanked him for doing so, with the assurance that she was often bored with the eternal conventionality of people in her social circle.

Suddenly turning from the commonplaces of the day, Gloria looked directly at Philip, and with easy self-possession turned the conversation to himself.

“I am wondering, Mr. Dru, why you came to West Point and why it is you like the thought of being a soldier?” she asked. “An American soldier has to fight so seldom that I have heard that the insurance companies regard them as the best of risks, so what attraction, Mr. Dru, can a military career have for you?”

Never before had Philip been asked such a question, and it surprised him that it should come from this slip of a girl, but he answered her in the serious strain of his thoughts.

“As far back as I can remember,” he said, “I have wanted to be a soldier. I have no desire to destroy and kill, and yet there is within me the lust for action and battle. It is the primitive man in me, I suppose, but sobered and enlightened by civilization. I would do everything in my power to avert war and the suffering it entails. Fate, inclination, or what not has brought me here, and I hope my life may not be wasted, but that in God’s own way, I may be a humble instrument for good. Oftentimes our inclinations lead us in certain directions, and it is only afterwards that it seems as if fate may from the first have so determined it.”

The mischievous twinkle left the girl’s eyes, and the languid tone of her voice changed to one a little more like sincerity.

“But suppose there is no war,” she demanded, “suppose you go on living at barracks here and there, and with no broader outlook than such a life entails, will you be satisfied? Is that all you have in mind to do in the world?”

He looked at her more perplexed than ever. Such an observation of life, his life, seemed beyond her years, for he knew but little of the women of his own generation. He wondered, too, if she would understand if he told her all that was in his mind.

“Gloria, we are entering a new era. The past is no longer to be a guide to the future. A century and a half ago there arose in France a giant that had slumbered for untold centuries. He knew he had suffered grievous wrongs, but he did not know how to right them. He therefore struck out blindly and cruelly, and the innocent went down with the guilty. He was almost wholly ignorant for in the scheme of society as then constructed, the ruling few felt that he must be kept ignorant, otherwise they could not continue to hold him in bondage. For him the door of opportunity was closed, and he struggled from the cradle to the grave for the minimum of food and clothing necessary to keep breath within the body. His labor and his very life itself was subject to the greed, the passion and the caprice of his over-lord.

“So when he awoke he could only destroy. Unfortunately for him, there was not one of the governing class who was big enough and humane enough to lend a guiding and a friendly hand, so he was led by weak, and selfish men who could only incite him to further wanton murder and demolition.

“But out of that revelry of blood there dawned upon mankind the hope of a more splendid day. The divinity of kings, the God-given right to rule, was shattered for all time. The giant at last knew his strength, and with head erect, and the light of freedom in his eyes, he dared to assert the liberty, equality and fraternity of man. Then throughout the Western world one stratum of society after another demanded and obtained the right to acquire wealth and to share in the government. Here and there one bolder and more forceful than the rest acquired great wealth and with it great power. Not satisfied with reasonable gain, they sought to multiply it beyond all bounds of need. They who had sprung from the people a short life span ago were now throttling individual effort and shackling the great movement for equal rights and equal opportunity.”

Dru’s voice became tense and vibrant, and he talked in quick sharp jerks.

“Nowhere in the world is wealth more defiant, and monopoly more insistent than in this mighty republic,” he said, “and it is here that the next great battle for human emancipation will be fought and won. And from the blood and travail of an enlightened people, there will be born a spirit of love and brotherhood which will transform the world; and the Star of Bethlehem, seen but darkly for two thousand years, will shine again with a steady and effulgent glow.”

THE VISION OF PHILIP DRU

LONG BEFORE PHILIP HAD FINISHED speaking, Gloria saw that he had forgotten her presence. With glistening eyes and face aflame he had talked on and on with such compelling force that she beheld in him the prophet of a new day.

She sat very still for a while, and then she reached out to touch his sleeve.

“I think I understand how you feel now,” she said in a tone different from any she had yet used. “I have been reared in a different atmosphere from you, and at home have heard only the other side, while at school they mostly evade the question. My father is one of the ’bold and forceful few’ as perhaps you know, but he does not seem to me to want to harm anyone. He is kind to us, and charitable too, as that word is commonly used, and I am sure he has done much good with his money.”

“I am sorry, Gloria, if I have hurt you by what I said,” answered Dru.

“Oh! never mind, for I am sure you are right,” answered the girl, but Philip continued—

“Your father, I think, is not to blame. It is the system that is at fault. His struggle and his environment from childhood have blinded him to the truth. To those with whom he has come in contact, it has been the dollar and not the man that counted. He has been schooled to think that capital can buy labor as it would machinery, the human equation not entering into it. He believes that it would be equivalent to confiscation for the State to say ’in regard to a corporation, labor, the State and capital are important in the order named.’ Good man that he means to be, he does not know, perhaps he can never know, that it is labor, labor of the mind and of the body, that creates, and not capital.”

“You would have a hard time making Father see that,” put in Gloria, with a smile.

“Yes!” continued Philip, “from the dawn of the world until now, it has been the strong against the weak. At the first, in the Stone Age, it was brute strength that counted and controlled. Then those that ruled had leisure to grow intellectually, and it gradually came about that the many, by long centuries of oppression, thought that the intellectual few had God-given powers to rule, and to exact tribute from them to the extent of commanding every ounce of exertion of which their bodies were capable. It was here, Gloria, that society began to form itself wrongly, and the result is the miserable travesty of to-day. Selfishness became the keynote, and to physical and mental strength was conceded everything that is desirable in life. Later, this mockery of justice, was partly recognized, and it was acknowledged to be wrong for the physically strong to despoil and destroy the physically weak. Even so, the time is now measurably near when it will be just as reprehensible for the mentally strong to hold in subjection the mentally weak, and to force them to bear the grievous burdens which a misconceived civilization has imposed upon them.”

Gloria was now thoroughly interested, but smilingly belied it by saying, “A history professor I had once lost his position for talking like that.”

The young man barely recognized the interruption.

“The first gleam of hope came with the advent of Christ,” he continued. “So warped and tangled had become the minds of men that the meaning of Christ’s teaching failed utterly to reach human comprehension. They accepted him as a religious teacher only so far as their selfish desires led them. They were willing to deny other gods and admit one Creator of all things, but they split into fragments regarding the creeds and forms necessary to salvation. In the name of Christ they committed atrocities that would put to blush the most benighted savages. Their very excesses in cruelty finally caused a revolution in feeling, and there was evolved the Christian religion of to-day, a religion almost wholly selfish and concerned almost entirely in the betterment of life after death.”

The girl regarded Philip for a second in silence, and then quietly asked, “For the betterment of whose life after death?”

“I was speaking of those who have carried on only the forms of religion. Wrapped in the sanctity of their own small circle, they feel that their tiny souls are safe, and that they are following the example and precepts of Christ.

“The full splendor of Christ’s love, the grandeur of His life and doctrine is to them a thing unknown. The infinite love, the sweet humility, the gentle charity, the subordination of self that the Master came to give a cruel, selfish and ignorant world, mean but little more to us to-day than it did to those to whom He gave it.”

“And you who have chosen a military career say this,” said the girl as her brother joined the pair.

To Philip her comment came as something of a shock, for he was unprepared for these words spoken with such a depth of feeling.

Gloria and Philip Dru spent most of graduation day together. He did not want to intrude amongst the relatives and friends of his classmates, and he was eager to continue his acquaintance with Gloria. To the girl, this serious-minded youth who seemed so strangely out of tune with the blatant military fanfare, was a distinct novelty. At the final ball she almost ignored the gallantries of the young officers, in order that she might have opportunity to lead Dru on to further self-revelation.

The next day in the hurry of packing and departure he saw her only for an instant, but from her brother he learned that she planned a visit to the new Post on the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass where Jack Strawn and Philip were to be stationed after their vacation.

Philip spent his leave, before he went to the new Post, at his Kentucky home. He wanted to be with his father and mother, and he wanted to read and think, so he declined the many invitations to visit.

His father was a sturdy farmer of fine natural sense, and with him Philip never tired of talking when both had leisure.

Old William Dru had inherited nothing save a rundown, badly managed, heavily mortgaged farm that had been in the family for several generations. By hard work and strict economy, he had first built it up into a productive property and had then liquidated the indebtedness. So successful had he been that he was able to buy small farms for four of his sons, and give professional education to the other three. He had accumulated nothing, for he had given as fast as he had made, but his was a serene and contented old age because of it. What was the hoarding of money or land in comparison to the satisfaction of seeing each son happy in the possession of a home and family? The ancestral farm he intended for Philip, youngest and best beloved, soldier though he was to be.

All during that hot summer, Philip and his father discussed the ever-growing unrest of the country, and speculated when the crisis would come, and how it would end.

Finally, he left his home, and all the associations clustered around it, and turned his face towards imperial Texas, the field of his new endeavor.

He reached Fort Magruder at the close of an Autumn day. He thought he had never known such dry sweet air. Just as the sun was sinking, he strolled to the bluff around which flowed the turbid waters of the Rio Grande, and looked across at the gray hills of old Mexico.

LOST IN THE DESERT

AUTUMN DRIFTED INTO WINTER, AND then with the blossoms of an early spring, came Gloria.

The Fort was several miles from the station, and Jack and Philip were there to meet her. As they paced the little board platform, Jack was nervously happy over the thought of his sister’s arrival, and talked of his plans for entertaining her. Philip on the other hand held himself well in reserve and gave no outward indication of the deep emotion which stirred within him. At last the train came and from one of the long string of Pullmans, Gloria alighted. She kissed her brother and greeted Philip cordially, and asked him in a tone of banter how he enjoyed army life. Dru smiled and said, “Much better, Gloria, than you predicted I would.” The baggage was stored away in the buck-board, and Gloria got in front with Philip and they were off. It was early morning and the dew was still on the soft mesquite grass, and as the mustang ponies swiftly drew them over the prairie, it seemed to Gloria that she had awakened in fairyland.

At the crest of a hill, Philip held the horses for a moment, and Gloria caught her breath as she saw the valley below. It looked as if some translucent lake had mirrored the sky. It was the countless blossoms of the Texas blue-bonnet that lifted their slender stems towards the morning sun, and hid the earth.

Down into the valley they drove upon the most wonderfully woven carpet in all the world. Aladdin and his magic looms could never have woven a fabric such as this. A heavy, delicious perfume permeated the air, and with glistening eyes and parted lips, Gloria sat dumb in happy astonishment.

They dipped into the rocky bed of a wet weather stream, climbed out of the canyon and found themselves within the shadow of Fort Magruder.

Gloria soon saw that the social distractions of the place had little call for Philip. She learned, too, that he had already won the profound respect and liking of his brother officers. Jack spoke of him in terms even more superlative than ever. “He is a born leader of men,” he declared, “and he knows more about engineering and tactics than the Colonel and all the rest of us put together.” Hard student though he was, Gloria found him ever ready to devote himself to her, and their rides together over the boundless, flower studded prairies, were a never ending joy. “Isn’t it beautiful—Isn’t it wonderful,” she would exclaim. And once she said, “But, Philip, happy as I am, I oftentimes think of the reeking poverty in the great cities, and wish, in some way, they could share this with me.” Philip looked at her questioningly, but made no reply.

A visit that was meant for weeks transgressed upon the months, and still she lingered. One hot June morning found Gloria and Philip far in the hills on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. They had started at dawn with the intention of breakfasting with the courtly old haciendado, who frequently visited at the Post.

After the ceremonious Mexican breakfast, Gloria wanted to see beyond the rim of the little world that enclosed the hacienda, so they rode to the end of the valley, tied their horses and climbed to the crest of the ridge. She was eager to go still further. They went down the hill on the other side, through a draw and into another valley beyond.

Soldier though he was, Philip was no plainsman, and in retracing their steps, they missed the draw.

Philip knew that they were not going as they came, but with his months of experience in the hills, felt sure he could find his way back with less trouble by continuing as they were. The grass and the shrubs gradually disappeared as they walked, and soon he realized that they were on the edge of an alkali desert. Still he thought he could swing around into the valley from which they started, and they plunged steadily on, only to see in a few minutes that they were lost.

“What’s the matter, Philip?” asked Gloria. “Are we lost?”

“I hope not, we only have to find that draw.”

The girl said no more, but walked on side by side with the young soldier. Both pulled their hats far down over their eyes to shield them from the glare of the fierce rays of the sun, and did what they could to keep out the choking clouds of alkali dust that swirled around them at every step.

Philip, hardened by months of Southwestern service, stood the heat well, except that his eyes ached, but he saw that Gloria was giving out.

“Are you tired?” he asked.

“Yes, I am very tired,” she answered, “but I can go on if you will let me rest a moment.” Her voice was weak and uncertain and indicated approaching collapse. And then she said more faintly, “I am afraid, Philip, we are hopelessly lost.”

“Do not be frightened, Gloria, we will soon be out of this if you will let me carry you.”

Just then, the girl staggered and would have fallen had he not caught her.

He was familiar with heat prostration, and saw that her condition was not serious, but he knew he must carry her, for to lay her in the blazing sun would be fatal.

His eyes, already overworked by long hours of study, were swollen and bloodshot. Sharp pains shot through his head. To stop he feared would be to court death, so taking Gloria in his arms, he staggered on.

In that vast world of alkali and adobe there was no living thing but these two. No air was astir, and a pitiless sun beat upon them unmercifully. Philip’s lips were cracked, his tongue was swollen, and the burning dust almost choked him. He began to see less clearly, and visions of things he knew to be unreal came to him. With Spartan courage and indomitable will, he never faltered, but went on. Mirages came and went, and he could not know whether he saw true or not. Then here and there he thought he began to see tufts of curly mesquite grass, and in the distance surely there were cacti. He knew that if he could hold out a little longer, he could lay his burden in some sort of shade.

With halting steps, with eyes inflamed and strength all but gone, he finally laid Gloria in the shadow of a giant prickly pear bush, and fell beside her. He fumbled for his knife and clumsily scraped the needles from a leaf of the cactus and sliced it in two. The heavy sticky liquid ran over his hand as he placed the cut side of the leaf to Gloria’s lips. The juice of the plant together with the shade, partially revived her. Philip, too, sucked the leaf until his parched tongue and throat became a little more pliable.

“What happened?” demanded Gloria. “Oh! yes, now I remember. I am sorry I gave out, Philip. I am not acclimated yet. What time is it?”

After pillowing her head more comfortably upon his riding coat, Philip looked at his watch. “I—I can’t just make it out, Gloria,” he said. “My eyes seem blurred. This awful glare seems to have affected them. They’ll be all right in a little while.”

Gloria looked at the dial and found that the hands pointed to four o’clock. They had been lost for six hours, but after their experiences, it seemed more like as many days. They rested a little while longer talking but little.

“You carried me,” said Gloria once. “I’m ashamed of myself for letting the heat get the best of me. You shouldn’t have carried me, Philip, but you know I understand and appreciate. How are your eyes now?”

“Oh, they’ll be all right,” he reiterated, but when he took his hand from them to look at her, and the light beat upon the inflamed lids, he winced.

After eating some of the fruit of the prickly pear, which they found too hot and sweet to be palatable, Philip suggested at half after five that they should move on. They arose, and the young officer started to lead the way, peeping from beneath his hand. First he stumbled over a mesquite bush directly in his path, and next he collided with a giant cactus standing full in front of him.

“It’s no use, Gloria,” he said at last. “I can’t see the way. You must lead.”

“All right, Philip, I will do the best I can.”

For answer, he merely took her hand, and together they started to retrace their steps. Over the trackless waste of alkali and sagebrush they trudged. They spoke but little but when they did, their husky, dust-parched voices made a mockery of their hopeful words.

Though the horizon seemed bounded by a low range of hills, the girl instinctively turned her steps westward, and entered a draw. She rounded one of the hills, and just as the sun was sinking, came upon the valley in which their horses were peacefully grazing.

They mounted and followed the dim trail along which they had ridden that morning, reaching the hacienda about dark. With many shakings of the hand, voluble protestations of joy at their delivery from the desert, and callings on God to witness that the girl had performed a miracle, the haciendado gave them food and cooling drinks, and with gentle insistence, had his servants, wife and daughters show them to their rooms. A poultice of Mexican herbs was laid across Philip’s eyes, but exhausted as he was he could not sleep because of the pain they caused him.

In the morning, Gloria was almost her usual self, but Philip could see but faintly. As early as was possible they started for Fort Magruder. His eyes were bandaged, and Gloria held the bridle of his horse and led him along the dusty trail. A vaquero from the ranch went with them to show the way.

Then came days of anxiety, for the surgeon at the Post saw serious trouble ahead for Philip. He would make no definite statement, but admitted that the brilliant young officer’s eyesight was seriously menaced.

Gloria read to him and wrote for him, and in many ways was his hands and eyes. He in turn talked to her of the things that filled his mind. The betterment of man was an ever-present theme with them. It pleased him to trace for her the world’s history from its early beginning when all was misty tradition, down through the uncertain centuries of early civilization to the present time.

He talked with her of the untrustworthiness of the so-called history of to-day, although we had every facility for recording facts, and he pointed out how utterly unreliable it was when tradition was the only means of transmission. Mediocrity, he felt sure, had oftentimes been exalted into genius, and brilliant and patriotic exclamations attributed to great men, were never uttered by them, neither was it easy he thought, to get a true historic picture of the human intellectual giant. As a rule they were quite human, but people insisted upon idealizing them, consequently they became not themselves but what the popular mind wanted them to be.

He also dwelt on the part the demagogue and the incompetents play in retarding the advancement of the human race. Some leaders were honest, some were wise and some were selfish, but it was seldom that the people would be led by wise, honest and unselfish men.

“There is always the demagogue to poison the mind of the people against such a man,” he said, “and it is easily done because wisdom means moderation and honesty means truth. To be moderate and to tell the truth at all times and about all matters seldom pleases the masses.”

Many a long day was spent thus in purely impersonal discussions of affairs, and though he himself did not realize it, Gloria saw that Philip was ever at his best when viewing the large questions of State, rather than the narrower ones within the scope of the military power.

The weeks passed swiftly, for the girl knew well how to ease the young Officer’s chafing at uncertainty and inaction. At times, as they droned away the long hot summer afternoons under the heavily leafed fig trees in the little garden of the Strawn bungalow, he would become impatient at his enforced idleness. Finally one day, after making a pitiful attempt to read, Philip broke out, “I have been patient under this as long as I can. The restraint is too much. Something must be done.”

Somewhat to his surprise, Gloria did not try to take his mind off the situation this time, but suggested asking the surgeon for a definite report on his condition.

The interview with the surgeon was unsatisfactory, but his report to his superior officers bore fruit, for in a short time Philip was told that he should apply for an indefinite leave of absence, as it would be months, perhaps years, before his eyes would allow him to carry on his duties.

He seemed dazed at the news, and for a long time would not talk of it even with Gloria. After a long silence one afternoon she softly asked, “What are you going to do, Philip?”

Jack Strawn, who was sitting near by, broke out—“Do! why there’s no question about what he is going to do. Once an Army man always an Army man. He’s going to live on the best the U.S.A. provides until his eyes are right. In the meantime Philip is going to take indefinite sick leave.”

The girl only smiled at her brother’s military point of view, and asked another question. “How will you occupy your time, Philip?”

Philip sat as if he had not heard them.

“Occupy his time!” exclaimed Jack, “getting well of course. Without having to obey orders or do anything but draw his checks, he can have the time of his life, there will be nothing to worry about.”

“That’s just it,” slowly said Philip. “No work, nothing to think about.”

“Exactly,” said Gloria.

“What are you driving at, Sister. You talk as if it was something to be deplored. I call it a lark. Cheer the fellow up a bit, can’t you?”

“No, never mind,” replied Philip. “There’s nothing to cheer me up about. The question is simply this: Can I stand a period of several years’ enforced inactivity as a mere pensioner?”