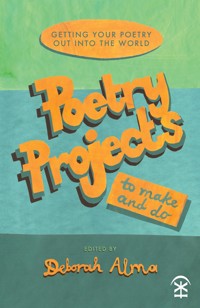

Poetry Projects to Make and Do E-Book

16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nine Arches Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Poetry Projects to Make and Do, edited by Deborah Alma, The Emergency Poet, is a 'how to' handbook of essays, prompts, advice, and ideas designed to help both aspiring and established poets find new ways not only to create new poetry, but to share and take it out into the world through collaboration, projects, performances – and more. With an array of real-life examples from experienced poets, Poetry Projects to Make and Do provides imaginative case-studies and inspiration for readers to roll up their sleeves and get stuck in. Each essay encourages experimentation alongside plenty of practical tips and guidance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Poetry Projects

to Make and Do

Poetry Projects to Make and Do

Edited by Deborah Alma

ISBN: 978-1-913437-62-6

eISBN: 978-1-913437-63-3

Copyright © the individual authors.

Cover artwork and all page motifs © Sophie Herxheimer.

www.sophieherxheimer.com

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, recorded or mechanical, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The individual authors have asserted their rights under Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of their work.

First published November 2023 by:

Nine Arches Press

Unit 14, Sir Frank Whittle Business Centre,

Great Central Way, Rugby.

CV21 3XH

United Kingdom

www.ninearchespress.com

Printed in the United Kingdom on recycled paper by: Imprint Digital

Nine Arches Press is supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

Contents

INTRODUCTION:Deborah AlmaOn Making It Happen

PART ONE: Projects Just For You

Roz GoddardNetting the Golden Fish: Reading Like a Poet

Nina Mingya PowlesPaper Journeys: Making Poetry Zines

Sophie HerxheimerOn Interplay: Image, Language, and Sound

Arji ManuelpillaiSo, You Wanna Make a Podcast?

Tamar YoseloffInnovation and Intervention: Making Poetry Pamphlets

Jane BurnPaint and Poems: The Aggregate Life

Helen DewberyMaking a Poetry Film

Caleb ParkinMycelia, Hedgerows and Tupperware: the Practical Sides of Wellbeing for Poets

PART TWO: Projects for Groups and Creative Collaborations

Casey BaileyWhy Collaborate? Let Me Burn Your Page and Show You the Ash

Jasmine GardosiWorking with Music: Ten Things I’ve Learnt

Gregory LeadbetterPoetry, Photography, and the Making of Balanuve

Helen IvoryThe Poetry Feedback Group

Clare ShawWorking with Vulnerability in Groups

Pat EdwardsCreating your own ‘Poetry Community’: Giving Back, Taking Part, Reviewing, Reading, and Making Space for Others

Jonathan DavidsonFunding Your Plans

PART THREE: Projects in Public

Julia BirdLearning to Loom: Producing, Staging and Touring Poetry Shows

Jo BellThere’s a Unicorn in the Staff Canteen! Being a Poet in Residence

Degna StoneUnfolding, Meandering and Falling: The Art of Responding to a Commission

Daisy Henwood & Lewis BuxtonHow to Make Toast: Producing Poetry Events

Jacqueline SaphraThe Theatre of Poetry and the Poetry of Theatre

Roshni BeeharryTaking Poetry into Unexpected Places: Writing with Healthcare Staff, Students and Those with Health Conditions

Jean AtkinWriting in the Community

Jane CommaneStanding in the Rain Together: Why We Should Take Poetry Out Into the World

Further Reading

Biographies

About the author and this book

Deborah Alma

Introduction: On Making It Happen

There’s an internet meme I came across with a quote from Buddhist teacher, author and nun Pema Chodron set against a wild and stormy Himalayan backdrop.

Let your curiosity be greater than your fear.

I usually find inspirational memes really irritating, but this one got through somehow. As I write this, about to set off towards the mountain of another project that’s too big for me, there it was! These words more-or-less sum me up.

First comes the idea, the project, the sense of adventure. This is exciting. It’s like falling in love. Something chemical happens in the brain; you’re hooked. For me the approach to a new project feels like my approach to a new poem. They have in common a state of receptiveness, playfulness and being open to the most fantastical of possibilities. I have learnt to lean into the idea and start to move in that direction however far-fetched it may seem and begin to have conversations with friends and potential collaborators. Those first steps are significant. Somehow a good idea can then take on a life of its own and a forward momentum. You find you’ve started something.

For me, this is not the time to look too hard at the possible pitfalls. It’s a state of creativity, visualisation and imagination. The reasons not to do this project will come crowding in later. If you write a checklist at this stage, it may get you nowhere and the idea may be abandoned too soon. Don’t expect to have everything in place; you don’t need to have all the answers to how or even why at this stage. Delight in disorder. (Robert Herrick). This attitude of receptivity and flexibility will serve you in good stead once your project starts to come to life and starts to go where it needs to go.

I remember feeling this sense of being taken over by excitement when I came across a 1950’s ambulance for sale on eBay back in 2011 and immediately visualised what was to become the long-running Emergency Poet project. Travelling dressed as a doctor, with Nurse Verse and a pharmacy of poetry in pills under the awning; I could see it all in my imagination even as I was bidding in the auction. I think that there was not one person at the time amongst my friends and family who thought that this was a sensible idea. The naysayers are useful however – they may have good and valid points and your answers will test both the idea and your resolve. I must admit to also wanting to prove them wrong. I enjoyed the risk, which was not as risky as it seemed in actual fact. Although I was a low-income single parent and bought it with my overdraft facility, at the same time I knew I could always sell it and get my money back.

For me it was important to have an attitude that I would either ‘succeed’ or learn something. There was no such thing as failure. To allow oneself to enter this apparently naïve state may not be easy. You may have to let go of a little dignity and stop caring what other people think of you. The vintage ambulance parked outside our house was an agony for my then teenage sons and the neighbours. They had to get used to it. The fact is that most people will think of what you’re up to only fleetingly, if at all and get on with their own lives. It doesn’t matter. You will be doing what you want to do. This can be a great place of self-actualisation, however small. Your life and your work are becoming the same thing. This I believe is a great achievement. Congratulations!

I seem to have an extreme case of the making-it-happen disease. I grew up in a household where we waited until we had enough money / time / energy to paint the room / go on holiday / move job or house; waiting for all the ducks to line up prettily in a row. Of course, those ducks kept shifting about and nothing got done. I resolved not to be like that. I may have overdone it.

In each project or undertaking, I always and quite early on, consider my fallback position. What’s the worst that can happen? If that’s not so bad, that’s your safety net. My safety net is a very comfortable one involving tea, cake and friends. Your own safety net is always there and knowing it’s there will get you through the bad days – a little spring in the net and up you get. The safety net with the ambulance was improving a vintage vehicle with the potential of selling it on if necessary (and in fact when I did eventually sell it, it had gone up in value). Later, and after one unsuccessful Arts Council bid, there was a second attempt and a little bit of funding support to enable me to do things better. Maybe some external funding can be your safety net, although I was determined to do it anyway and I think the Arts Council like to know this about a project.

You will explore new things; you will learn and grow, and learn when to change direction, re-think or do things differently. There can be no failure, only adaptation or growth. You will be altogether more contented and properly yourself in the world. This is an attractive and energetic state and draws towards it people that want to work with you. You will find yourself on an upward spiral; it’s still hard work but very rewarding.

Don’t confuse this naïve state with ignorance. It can seem that way to people looking-on. It is just seeing the most positive outcome and working towards that. Ignorance is all about not looking and avoiding the problems – don’t do that! It’s just that the received wisdoms, the sensible approach, the properly costed, the mature decision can be a chimera; something hoped for but impossible to achieve. I don’t at all mean to advocate recklessness; remember you have always have your safety net; but what have you got to lose? You really have so much to gain.

If your project necessarily involves working with or for others, it makes sense that you are properly part of these communities and then you will have worked with them already and know how they work. I remember when my friend Dr Katie Amiel and I were talking of putting together the poetry anthology These Are the Hands – Poems from the Heart of the NHS we had first to find a publisher. We could have approached a large/mainstream publisher with Michael Rosen and the Royal College of General Practitioners on board, but I had worked with my good friend and publisher Nadia Kingsley of Fair Acre Press when editing #Metoo – Rallying against sexual assault and harassment – a women’s poetry anthology and it had been a great pleasure to work with her. We worked well together, plus she was retraining to become a GP. It felt right.

I’m a firm believer in a kind of karmic attitude to working on projects. I believe that in order to ask something of a community you must first have given and given some more. In the world of poetry, this means you buy the books, go to the open mics, read the poems of friends and others, and share their successes, workshops and readings on your social media and more. Only then can you ask. I don’t mean this cynically – that you give only in order to receive – but that you involve yourself in a community so you work with relationships that are real and authentic. It is not who you know, but how you know them. And thank you so much Nadia for both of those books!

When working collaboratively, start from a position of ‘I don’t need anything from you, but what can we do together?’ Be open to ideas and suggestions from others, listen really carefully to each other and learn what is realistic to expect from each other in terms of commitment, time and energy. Be prepared to be flexible when people can’t do as much as they had hoped.

I also learnt that if people offer to help, always say ‘yes’. Someone else’s energy, belief and generosity for your project is too valuable to turn down, even if it’s hard to accept – there will always be something they can do. If you find it uncomfortable to work alongside someone or to hand over too much control, try asking them to distribute flyers, or help set up a room, or simply to share something on social media. I have learnt that people really do like to be involved.

If you can, surround yourself with people that believe in your project, their confidence will buoy you up when you falter. They may become the place to express any vulnerabilities and uncertainties, may assist with lightening the workload, and can play a crucial role in developing resilience.

* * *

There’s plenty of excellent advice in this book on the nuts and bolts of bringing your project to life; Jonathan Davidson’s excellent essay advises on how to attract funding, Caleb Parkin reminds us to look after ourselves as creative people in the process, Clare Shaw speaks eloquently of working with vulnerability when working with groups, and Jean Atkin has good advice on making a living as a writer in the community. All of the essays provide ideas, advice and insights, that range from setting up some space and time for yourself to write and think, right through to working with groups in a wide range of settings. You will find inspiration, wisdom and practical solutions and heads-up for the potential pitfalls.

The book is divided into three distinct sections. The first section, Projects Just For You, includes essays for developing and extending your own practice as a poet; these include Jane Burn who writes about the interconnectedness of her visual and written art, Roz Goddard reminding us of how to read mindfully in order to develop our writing practice, and Nina Mingya Powles inspiring us to think about zine-making.

In Part Two, the essays are concerned with working with groups or in collaboration with others; from Casey Bailey asking the question about why collaboration can be so enriching, to Jasmine Gardosi exploring working with musicians, and Pat Edwards on making space for the work of others in some way, whether it’s in reviewing or literally making space to hear other poets in a festival or open-mic setting.

The last section of the book is concerned with creating new poetry projects in the public sphere and making a living as a poet in the world; from Jane Commane’s essay on taking poetry out into the world, to Jo Bell’s essay on setting up residencies, and Degna Stone’s guidance on commissions and drawing inspiration in museum and gallery spaces, all of which offer practical advice and ideas. There’s plenty more here also on setting up live and touring performances, taking poetry into theatrical spaces, and projects in other more unusual settings such as in healthcare.

Behind and beyond all of this excellent advice are the ideas and will and drive in the first place. This is what will make it happen – you –and you are brilliant. I would like this book to be the gentle hand in the small of your back saying ‘Go on. Go on. You can do it.’

ACTIVITY: Small and easy-to-swallow purgatives for writer’s block, stimulants for novel ideas & curatives

for sluggish blood

Cultivate boredom. A place between is essential for new ideas. Take steps to find this space. Is it a short train journey? A coffee shop that’s particularly unstimulating? Keep your notebook in your bag or pocket.

Write a few sentences about an experience you had of doing something for the first time that you thought you couldn’t do and that now comes pretty easily to you, e.g. riding a bike, using a computer, a new mobile phone.

Identify what’s blocking your writing – address a curse in its name. Write the curse in red ink and bury it in the garden or in a plant pot.

Have you ever entered a house or room when you shouldn’t have? Write about the experience. Describe the room in minute detail, as well as your feelings. What did you find?

Write a list (no need to be definitive) of ten books you have loved or that have some meaning to for you in some way. By each book, write three words you’d use to describe it, or which take you to the time of reading. Find connections with what you have written.

Write a poem or piece of writing infused with a colour, without actually naming the colour. See if you can make it painterly, e.g. an imaginative walk encountering a frog, a fern curling, a glass of lime juice.

If you could take a week outside of your everyday life to do nothing but read and write, where would you go? Describe your week. What do you need?

Sit still and quiet, and listen. Listen and identify each of the sounds you can hear. Write them down; the pipes rushing with water, a passing car, a floorboard thud from another flat. Keep going until you come upon a sound that you can’t identify. What might it be?

Part One

Projects Just For You

Roz Goddard

Netting the Golden Fish: Reading Like a Poet

When I was a teenager in the seventies filling notebooks with outpourings of dark feelings and notions, my father paid good money to have my poems published. I spotted a small ad in the Daily Mirror asking poets to submit their best poems for inclusion in an anthology – which I duly did. The reply was encouragingly swift and let me know I was the new Sylvia Plath and could I send £40 for inclusion in the anthology? My dad paid up. The anthology, when it arrived, was a green exercise book with my poems squashed toward the bottom of page eighty-three. I’ve never forgotten the disappointed surprise tinged with shame – it woke me up somewhat. I knew nothing then. I didn’t read poetry. Why bother? I was a genius. I like to think Dad’s money wasn’t wasted – I read lots of poetry now, some of which are fully accessible in the library of my heart.

My long-time friend and poet Jonathan Davidson is an advocate of reading poems slowly, giving them their due attention, often returning to them over a period of years. On a recent walk, he produced from his wallet a fragile and many-times folded copy of the W. S. Graham poem ‘Johann Joachim Quantz’s Five Lessons’ – a poem that has been a companion to him for over thirty years: “when solace is required, it is this little piece of genius that I reach for.”

In his recently published essay ‘The Slow Poetry Movement’ (Redden Press, 2023), he advocates experiencing “as deeply as possible the pleasures and illuminations that can unfold from spending time with a poem”. I agree.

I can remember the moment I came across Katherine Mansfield’s poem ‘Pulmonary Tuberculosis’. It felt like I’d been waiting for it my whole life – an ‘Oh, I see’ moment. I seemed to have gone beyond my initial comprehension of the poem – an intellectual understanding if you like – to access a deeper resonance that tapped into an experience of illness I instinctively knew could open significant doors to new ways of thinking for me.

Mansfield suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis for much of her life and was regularly treated in sanatoriums for her illness. Here’s the poem:

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

The man in the room next to mine has the same complaint

as I. When I wake in the night I hear him turning. And then he

coughs. And I cough. And after a silence I cough. And he

coughs again. This goes on for a long time. Until I feel we are

like two roosters calling to each other at a false dawn. From

far-away hidden farms.

Since I was young, I’ve been deeply affected by illness. My mother was gravely ill when I was a child and I remember that painful, twilight time of not knowing whether she would live or die. During those days of my mother’s illness, reading became a sanctuary in the uncertainty and sadness. I read Johanna Spyri’s Heidi over and over, finding thrill and solace in a child’s life on the mountainside under the big, open sky – a fantasy landscape far from my Black Country street with its booming power forges and mysterious warehouses. The stoicism and beauty of the Mansfield poem appeals to me: the scene, the stuckness of two people in illness – together but separate. They are fellow travellers communicating beyond words. It illustrates the tenderness and compassion that can be felt when witnessing the pain of others – it’s a poem about our human predicament and the choices we have in how we deal with sorrow and helplessness. Mansfield is an observer of her experience as well as being in it.

I was diagnosed with breast cancer at the end of 2020 and, during that time of deep anxiety, I returned to this poem to remind myself that I’m not alone and also that I have a choice about how I view and assimilate my experience.

If I can bear to be with the pain of diagnosis, what it might mean for my future, be tender with the experience – it could be helpful.

Our reading choices are always telling us something about where we’re at in our lives. Currently my addiction to soft-boiled crime fiction is telling me I’m feeling overwhelmed in my life and need to carve out some time to enter the world of forensic archaeology, sand dunes and peril that isn’t my own. I’m pulled along by the propulsive narrative, lightly-sketched characters and a desire for certainty my own life can’t deliver. If I reflect on my reading habits – it always brings me closer to myself; getting closer to myself opens up my choices about how I live – I’m observing rather than simply consuming.

I often lead poetry writing workshops and begin the session with a period of mindful reading practice – an opportunity to read in silence together, uninterrupted in a conducive space. Maybe you’d like to try it for twenty minutes? Here goes: Select a book pretty much at random from your shelf. Sit down somewhere comfy and, as you read, become aware of how you’re reading. This might include noting the pace you read: fast or slow? Is the text causing a particular response? Maybe it’s speaking deeply to you or causing resistance. Notice what’s resonating. Stay with the words or phrases, perhaps writing down what you find interesting. Is the text speaking deeply to you? What’s it saying? How does it make you feel?

It’s an instructive exercise as it’s rare to examine how we read rather than what we’re reading. I was recently reading a poet new to me and was surprised by how resistant I was to the work: it was thematically challenging and formally difficult, and my attention regularly drifted off. During a pause, I wondered how this might be a richer experience for me – the answer was to give the poetry a better quality of attention; my mind was dismissing the work too soon.

I often follow the mindful reading session with a led meditation which you’ll find in the appendix – it seems to be a good companion to the sense of awareness that’s been developed from mindful reading. As a practising Buddhist, I meditate regularly. Meditation has been described as the “art of being with oneself” or as Alan Watts has written “being in the eternal flow”. It’s a stillness practice that brings me back to myself by deepening my awareness of feelings, emotions and thoughts – like catching a net of golden fish as they swim up. What I discover can be surprising, difficult, beautiful. I’ve found that sitting still over a period of time opens up new spaces in myheart and mindinto which diverse ideas have the opportunity to incubate and flower – in other words, the ideal conditions for new poems to emerge.

I’m currently fascinated by Zuihitsu, a form of Japanese poetry that feels like a poetic partner to meditation. In her 2006 collection of poems, The Narrow Road to the Interior, Kimiko Hahn muses on its definition. She looks for something that comes close to “a sense of disorder that feels so integral” and finds Donald Keene’s definition that, with its urgency and instinctual composition, Zuihitsu “follows the impulse of the brush”.

I wanted to explore the idea of following the ‘impulse of the pen’. Those of us who have attended writing workshops over the years will be familiar with the automatic writing ‘killing the white’ or freewriting exercise designed to subvert the judging mind and produce a more natural flow of writing. I’m discovering in my own writing that by going deeper into an image or feeling, a rich flow of fragments and juxtapositions start to shine that seem to come from a place between the heart and the belly – a flow around a theme combined with a surprising tone that I’m enjoying.

Meditation and silence have helped me conceive and approach a different way of writing – not an intellectual, thought-through process but rather an instinctive response to the deepest rivers of my feelings and experience, being alive to what it means to be alive in all its complexity and how I might express that creatively.

Recently, I’ve returned to keeping a journal as a way of systematically accessing my thoughts and feelings – trying to truthfully record how I feel about the heartache and joys of my life. I returned to Marion Milner’s A Life of One’s Own, first published in 1934, in which she discovers that keeping a journal enables her to “plunge into the deeper waters of the mind … suggesting creatures whose ways I did not know.”

Her journal becomes a deep, and faithful record of her loves, hates and fears. Writing a journal seems to be a way of subverting the thinking mind, illuminating what I don’t know about myself in surprising and exhilarating ways.

After all, writing poetry is not a rational pursuit. I find thinking to be the enemy of writing poetry – particularly in the drafting stage. I recently shared a manuscript in progress with my editor; she enjoyed a section that had been written full pelt, Zuihitsu-style from the belly. I like it too, it’s full of blood and energy.

I came across a YouTube video of poet Ocean Vuong talking about his approach to teaching (he’s Professor of Creative Writing at NYU). He “doesn’t centre criticism”, rather the first five weeks in an Ocean Vuong poetry workshop is about encouraging students to “name the work”, to “get to know the ambition”. He’s interested in getting students to explore their writing territories to understand what the seabed of their deepest pulls and concerns are: “students discover the effects of their intent”. It seems to me that beginning to understand and own our obsessions and experiences is a dazzling gift we can give to ourselves. After a deeply traumatic experience, in which he nearly died, the poet David Whyte noticed how his voice had changed:

It was no longer up in my throat, ready to be given away and please others so readily. It settled in my stomach along with my breath … my voice could suddenly allow the presence of darker hidden energies I had previously left unexplored.

Where does reading feature in the “transcendental joy of composition”, as Don Paterson puts it? I recently listed my reading research for a sequence of poems I’m writing: Standing in the Forest of Being Alive (Katie Farris), the Rijksmuseum Vermeer catalogue, astrophotography, orchards, river behaviour, wild horses, characters in Tess of the D’Urbervilles, the manufacture of gold jewellery. The diversity of my sources seems to echo an intangible energy in my body and mind whose alchemy produces the poem draft – in other words, I don’t know what’s going on. What I do know is the dropping in of text, fragments, images and memories is exciting, but I’m clueless about where the poem will end up. David Whyte again:

… our ability to respond creatively, whether at our desks or on the yet unwritten page, depends on our ability to live with the unexplored territory of silence.

Wait, wait.

Years ago, I had a rejection from a poetry magazine. The editor liked the beginning of the poem yet found the end “rather striven for”. I didn’t understand then that life can’t be neatly tied up. I do now.

When I read a wonderful poem, it feels like blue ink has dissolved in a pool of clear water – the ripples carry on right to the edge then beyond the pond to a deeper place of understanding that gives me a unique glimpse of what it means to be alive.

ACTIVITY: Writing from the openness

Just sitting (10–15 mins).

Find a spot where you can be undisturbed for a time. Set yourself up in a comfortable position: sit on a chair or lie down on the floor or bed, and maybe cover yourself lightly with a blanket so you are warm enough. Give yourself the opportunity for this a period of stillness. Clench your fists really tight for a few moments then let go completely and relax back.

Stillness gives the body and mind an opportunity to settle. It allows us to step out of the zone of doing and into a space where simply being with what arises in our experience comes to the fore. We can witness the rhythm of our breath however it is, without interference.

Watch thoughts come and go – meditation is not about banishing your mind of thoughts. Scan your body for sensations of warmth, pleasure, pain – whatever’s there. Simply be with it without judgement.

At the end of the meditation, gently rise, noticing how your body and mind have responded to the stillness.

If you feel like writing, perhaps journal in a free and loose style about what arose for you.

Works Cited:

Katherine Mansfield, ‘Pulmonary Tuberculosis’: The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, Ed. Jeremy Noel-Tod, (Penguin, 2018)

David Whyte, The Heart Aroused: Poetry and the Preservation of the Soul in Corporate America (Doubleday, 1994)

Ocean Vuong on YouTube 'My Vulnerability is my Power':

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u5NuCrAkjGw

Joanna Field; Marion Milner, A Life of One's Own (Virago Press, 1986).

Nina Mingya Powles

Paper Journeys: Making Poetry Zines

I held my gaze on the horizon as the minibus sped through the desert. The bright white mountain range parallel to the highway sometimes appeared closer, then further away. My boyfriend, who I was travelling with, tapped my shoulder to look at the landscape on the other side of the road and I gasped: rows and rows of distant turbines, sunlight flashing on their white blades as they turned in unison. I had felt the raw wind of the desert; my cheeks still stung from it. I opened my phone camera and pointed it out the window at the sea of windmills, but the lens barely captured their outlines.

We had met just a few months earlier in Shanghai, where we were both living, and things between us had quickly intensified. In less than six weeks, we were both due to leave the city for our respective home countries, Aotearoa and the UK. We didn’t know what would happen next, only that we ought to go somewhere together. Xinjiang was a place neither of us had been, and was about as far away from ordinary life as we could get.

We had driven an hour from the city of Kashgar in China’s western Xinjiang Province, near the mountainous borders of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. I glanced at the pulsing blue dot on the map on my phone and wondered if this was the farthest I’d ever been from the ocean.

It was 2017, and the full extent of the Chinese Communist Party’s internment camps across the region was not yet known, though Kashgar in particular had seen a steadily growing military presence for several decades. I knew this, and yet the sight of heavily armoured vehicles and armed police dotted around what otherwise felt like a quiet and picturesque old city still shocked me. I was conscious that they watched us, but only out of curiosity; we were not locals and therefore not deemed a threat. Once we were stopped by a military policeman and asked – not threateningly, though he had an automatic rifle slung over his shoulder – why on earth we’d choose to visit ‘such a dangerous place.’

I was overwhelmed with the feeling of needing to remember everything we did and saw, to capture the entire trip before it slipped away – before everything changed. My camera roll was filled with pictures of desert structures and market stalls and clouds of purple bougainvillea. As I always did, I wrote down lists of images in my notebook:

blue mosaic tiles & tall sunflowers red tomato the size of a heartbaked lamb dumplingsthe smell of dried apricots

In the days after returning home, as my last day in the city came closer, I decided to make a new zine. I didn’t know who it was for: perhaps just for me. It would contain poem fragments, lists and images from the trip. Physical proof that all this really happened: the turbines, the mountain light, the blue glacial lake, his skin and mine. A poetry zine is something you can put together quickly – a poem object you can create yourself with little more than a few sheets of paper.

Much like a poem, a zine can be almost anything you want it to be. At its heart, a zine is a DIY publication of some kind, usually hand-folded and printed in small quantities. My first zines were poetry zines, but categories are flexible in the world of zines. You could make a travel zine, a photography zine, a protest zine, or something that’s all three. It could have drawings or collages or pictures; it could be long or short, handwritten or typed. Zinemaking, for me, lies somewhere in the exciting generative space between crafting poetry and journaling. When away from home, it’s given me a creative space to reflect. What does it mean to feel rooted in a place where I’m really a visitor? What does it mean to be a tourist in a country where locals cannot criticise their own government freely?

I copied and pasted a few landscape pictures I’d taken on my phone and digitally recoloured them in pale blue – something close to the colour of the sky and the surface of the high-altitude lake where we had stood. I scanned sections of pages from my notebook and cut them up with scissors. I typed up some lines I had written in my notebook, printed them out and placed them on top of the mountains.

* * *

The first zine I ever made was a booklet of ghost poems titled (auto)biography of a ghost. I secretly printed twenty copies in the photocopying room of the creative writing department. On the cover was a grainy black-and-white picture of a shadowy stairwell. I kept making poetry zines, and set up a little stall at my local annual zinefest. In Shanghai, I frequented my university’s campus print shop, where you dropped coins into a bucket next to the technician’s desk. While other students rushed to print copies of dissertations and exam papers, no one raised an eyebrow at my strange erasure poem printouts.

I also have a stack of notebooks from the eighteen months I lived as a student in Shanghai. Rather than diary entries, they are full of lists, recipes and images. Occasionally I taped train tickets and boarding passes inside, along with mini Polaroids taken with my blue Instax camera. This habit of recording and cataloguing my life only really started when I left my home country, and was perhaps fuelled by the many cheap and cavernous stationery stores close to campus where rows of fresh candy-coloured notebooks of all sizes and varieties greeted me upon entering.

I took my notebook everywhere I went – something I rarely do nowadays. I was often eating alone, which meant I often sat at a table by the window with a bowl of noodles and my notebook, making lists. Lists of Chinese characters to practise, lists of potential poem titles, lists of colours in the sky, lists of recurring dreams. On the crowded subway, I made notes on my phone of things I’d seen, places where I’d stopped to eat. Many of these lists, or fragments of them, later found their way into my first published poems.

What was it about leaving home that turned me into a note-taker? I was at the beginning of something, but I didn’t know what. I was living for the first time in two languages. I was overwhelmed by my new surroundings, all the colours and smells and tastes. After my daily Chinese classes, I wrote out sets of characters twenty times each, trying and mostly failing to commit them to muscle memory. I was playing with different forms, both poetic and linguistic. I was learning what my own creative process might look like. I can see now that my language learning was entangled with my zinemaking; at the same time as I cut up squares of paper into vocabulary flashcards, I was cutting scraps of calligraphy paper to fold into mini zines.

Zinemaking reminds me that poetry is physical. It’s a way to test out ideas, to try new things and allow myself to get lost in the meditative act of folding and stapling paper, of cutting out words and gluing lines together to make something new.

* * *

It took at least a day and night for me to grow accustomed to the quiet. From our flat near Hampstead Heath in London you could hear owls and teenagers whooping through the night; here in rural Scotland, the only sound was rain falling faintly on the skylight of the cottage. A small art gallery in Dumfriesshire had invited me for a week-long writing residency, and I found myself alone for the first time in many months. I wasn’t sure what I had come here to write, or if I’d be able to write at all. But I could make a zine. I could make a small poem object that hadn’t existed in the world before, and that would be enough.

The walk from my cottage to the gallery took thirty minutes each morning and evening. It was a mossy walk along a country lane lined with damp stone walls. Tiny ferns grew in the gaps in the stones and a spongy layer of moss enveloped all the branches. In some places the moss was so thick it pulled away from the surface of the bark like a heavy knitted garment. Each morning when I reached the gallery I was out of breath and my fingers were cold. In the evening when I got back to the cottage I felt tired from the effort of trying to generate creative energy. I made myself a bowl of instant noodles with a soft-boiled egg and a teaspoon of Laoganma chilli oil on top – I’d brought a few packets of noodles and a pottle of chilli oil with me from London – and sat down to watch a Netflix documentary about volcanic eruptions as the sky darkened outside the windows.

That night I had strange dreams involving lava deposits and moving islands. Tina, the gallery director, had given me a tourist leaflet with a map of the local area. I began cutting up the map along the blue lines that marked rivers and streams, creating a series of curved shapes. Using the office inkjet printer, I printed a picture of stones I had taken that morning and cut out a rough shape of a volcano. I folded a single sheet of A4 paper into a mini zine and arranged the cut shapes across it. I tried not to overthink their composition, instead being led by lines and shapes and blank space.

moss & pink stone walk is a mini zine documenting my walks around Dumfriesshire and my week spent in the stone cottage. I printed it on lilac office paper and folded it using a ruler to press the corners. Cutting up shapes and words to make poems was a liberating and calming process, and making something so specific to this particular time and place freed myself up to start writing again about other things. I knew this was a zine I’d only give to a handful of people, which made me feel free to experiment and not worry about crafting something too polished. The unfinished, imperfect nature of zines is what I love most about them.

Like submerging myself in cold water, being in a new place often reinvigorates my creative self. But since moving countries several times in my life, the distinction between feeling at home and away from home