20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

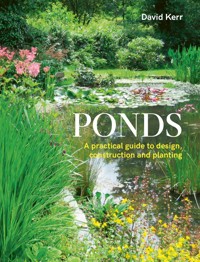

It's almost impossible to overstate the benefits of creating a well-planned pond in your garden or field. This detailed and practical guide will give the novice and experienced gardener alike a straightforward explanation of how to plan, construct and plant a thriving pond, avoiding common problems and establishing a haven for wildlife.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 276

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

First published in 2023 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© David Kerr, 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4254 2

Cover design by Nikki Ellis

CONTENTS

Introduction

Part One: Planning and Construction

1 Preliminary Planning

2 Tiny and Small Garden Ponds

3 Medium and Large Garden Ponds

4 Ponds on a Larger Scale

Part Two: Plants and Planting in the Pond

5 Plant Selection

6 Marginal Plants

7 Oxygenating and Deep-Water Plants

8 Water Lilies and Nuphars

9 Planting, Propagation Techniques and Pond Problems

10 Integrating the Pond with the Surrounding Area

Appendix I: Latin Names and Common Name Equivalents

Appendix II: Common Names and Latin Name Equivalents

Appendix III: Marginal Plant Characteristics

Suggested Further Reading

Useful Contacts

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

From an early age I was growing lettuces in a mixture of heavy clay and broken concrete, but I soon became fascinated by water and all the unfamiliar and strange things that live in it. My long-suffering parents tolerated an everincreasing number of holes appearing in their precious garden, filled with a variety of hastily constructed and poorly designed death traps in the guise of garden ponds. Slowly but surely, I began to understand why some ponds were successful and others not so much, and this learning process continues today. After achieving a degree in Zoology and a Masters in Fish Biology, I started a trout farm in Devon from scratch in 1982, while starting a popular sideline retailing aquatic plants, pond fish and pond accessories. In the winter months I constructed a wide variety of fishponds and garden ponds in connection with the expanding aquatic business. After selling the trout farm in the 1990s I moved to my current home in 2001, where I began to grow and sell aquatic plants by mail order under the name of Devon Pond Plants. This business has been tremendously successful, and I have learned a great deal more about what makes a pond work and how the different plants perform and grow. Through my website at devonpondplants.co.uk I have earned a reputation for straight talking and telling it how it is, and I will follow that strategy in this book. My aim is to cut out all the usual padding and concentrate on the main nuggets of information, adopting a practical rather than a theoretical approach. I will pass on some tips which have taken me many years to discover and share some insider knowledge which is hard to find for yourself.

Last year The Wildlife Aid Foundation embarked on its biggest ever life-changing project, part of which was to build three massive ponds for wildlife. Seeking specialist advice on aquatic planting, we reached out to David Kerr, who, after an initial consultation, quickly set about drawing up a very comprehensive plan for the design and planting of the area. His obvious knowledge and expertise left us in no doubt that we were in good and safe hands. What a breath of fresh air!

Simon Cowell, CEO of Wildlife Aid, and former presenter of Wildlife SOS.

ABOUT THIS BOOK

I hope that this book will allow the reader to leapfrog many of the errors commonly made and enable them to achieve success first time around. It is aimed at those with a reasonable level of practical ability and gardening knowledge, who nevertheless have limited experience of ponds and pond planting. It is therefore assumed that it is unnecessary to explain which tools will be necessary to dig a hole, or which way up a plant goes in the hole (green side up is a good general rule!). If you’re the sort of person who needs to be told that they need a wheelbarrow and spade, and be shown a picture of these, this book may not be for you. In particular, contractors and garden designers with limited previous experience of aquatic planting may find it very useful.

The aim is to provide the detail lacking in other texts to enable the optimum planting in a pond to maximise its wildlife value and aesthetic appeal. It is not intended to cover aspects such as pumps and filters, waterfalls and fountains, hard landscaping details or fish keeping matters. A successful planting scheme depends in large part on good design, so there is a substantial section explaining the importance of careful construction before the planting is covered in detail. There is a long and detailed section on the plants which are most likely to be available in the UK, together with the growing requirements of each. Practical advice relating to propagation and pond maintenance is given, and at the end there is a chapter on common problems and how to deal with them.

Typha flowers.

I make no apologies for primarily using the Latin binomial names for plants to avoid confusion; common names are given where available. The Latin binomial is given in italics. Common names are interesting but confusing, for example horsetail is Equisetum whereas marestail is Hippuris. Water willow can be Persicaria or Justicia and willow moss is Fontinalis. Almost everyone calls the tall marginal plants topped by brown pokers ‘bulrushes’, however they are in fact reed mace (Typha). Bulrushes (Schoenoplectus) have tall tubular dark green pith-filled leaves and small spikes of brown flowers. (Rushes typically have tubular type leaves, whereas reeds have flattened leaves, but people often use the terms interchangeably.) Very many local names exist for native plants, and this can add to confusion. A dictionary of Latin to common names and vice versa can be found in the Appendices at the back of the book. There you will also find various useful information tables and contacts.

WATER IN THE LANDSCAPE

Water is not just an essential part of the landscape, or part of life. Water is life. Natural ponds do differ from manmade ones in many ways, but a well-constructed and planted artificial pond is a valuable addition to any garden or field. A garden or piece of land containing water is a magnet for wildlife and is infinitely richer than one without. Even within minutes of filling a new pond, insects will arrive to check it out, and that very night you can be sure that mammals will visit too. In nature, ponds are relatively short lived, geologically speaking, since they steadily fill up with sediment and plant material, morphing into bogs and heathland. They are therefore transient, and the animals and plants that inhabit them have evolved to be able to cope with variations in water levels and indeed to be able to survive periods of total drought, while taking the opportunity during flooding to colonise new areas. Along with this strategy of colonisation and endurance comes a tendency to be fast growing, tough and invasive, so many water plants are not suitable for smaller ponds at all and need to be used with care even in very large ponds if a total takeover is to be avoided. Ponds without plants are biologically poor, even though the water quality may be excellent. In nature these are the relatively rare oligotrophic, or nutrient-poor, mountain lakes and tarns, into which little organic material finds its way. Levels of nitrates and phosphates are low, which means that plants are starved of plant food, therefore insects are mostly absent and larger animals have no food and no place to hide and reproduce. In lowland areas the input from rivers and streams carrying a high load of organic material makes ponds eutrophic, or nutrient-rich. At its extreme end this can mean that decomposition of this material produces toxic gases and other compounds which exclude the possibility of life. This is why woodland ponds are often problematic – the large quantity of fallen leaves can blanket the pond base and poison the water – but in open unwooded areas it means that there is an explosion of fast-growing plants. This in turn means that the pond rapidly silts up with organic material produced by and trapped by the plants, and in no time at all there is no pond at all, just an area of dense reedbed and marsh.

Water in the landscape.

Dragonfly on an iris bud.

Pond reverting to bog.

The principal difference between a natural pond and most artificial ones is that the former is connected hydraulically to ground water and there is a seamless progression from wet to dry at the edges, since there is no liner. This usually makes for a more variable water level, and it does not guarantee that the pond will not dry out completely when the ground water level drops. However, even if a geotextile liner is used, as typically on ponds over 200m2, the pond itself is cut off from the ground water and cannot be replenished from this source. On a hot summer’s day, a shallow lined pond could drop as much as 5cm from evaporation and transpiration, but ground water levels are unlikely to drop that fast, so in this way a lined pond is less stable than a natural one. In the case of on-stream ponds of course the water level will be more or less constant unless the stream dries up completely.

Progression of wetness at the margins.

In hot Middle Eastern countries, the value of water is perhaps understandably appreciated more highly, and cool oases with fountains and moving water have been a feature of wealthy homes for many hundreds of years, but in Great Britain, the interest in incorporating largescale artificial water features into private estates and gardens really only began fairly recently, with landscape architects such as Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, Gertrude Jekyll, Beth Chatto and the like. Few aquatic plants have a long history of cultivation and those that do are mostly those with practical uses such as thatching reed (Phragmites communis) or lotus, every part of which can be eaten in tropical or subtropical countries. The relatively low effort spent on developing new varieties of pond plants, coupled with the short history of water gardening, means that the range of commercially available aquatic plants is quite small when compared with the panoply of ordinary garden plants, and when this is combined with the need to avoid many undesirable species, it doesn’t leave a vast number of possibilities for planting. A few species, such as Caltha palustris (kingcup or marsh marigold), could be considered to be almost essential, but for most smaller ponds on a garden scale, the range of suitable plants is quite small. It is therefore vital to select the right ones and give these plants the best possible conditions to enable them to thrive.

Perfection of landscaping.

PART ONE: PLANNING AND CONSTRUCTION

CHAPTER 1

PRELIMINARY PLANNING

TYPES OF POND

Ponds can be artificially separated into many categories, such as ‘formal pond’, ‘fish pond’, ‘swimming pond’, ‘wildlife pond’, ‘ornamental pond’, ‘duck pond’ and so on, but any body of water will help wildlife to some extent.

Nine out of ten people, if asked, would say that the primary purpose of their pond is to encourage wildlife, but of course most also prefer to have a degree of control over the look of the pond too, and would want to consider it an attractive feature in the garden. Frankly, a newt doesn’t care about the colour scheme and would actively prefer a dense jungle of vegetation to a manicured look, so some degree of compromise is almost always necessary. Some choose to have more than one pond, with a tidier and more visually attractive look (to them) in the foreground and a slightly more unkempt version further down the garden ‘for wildlife’. Try to look at it from the point of view of the wildlife that you hope to attract. Animals require three main things: a hospitable environment in which to live, a hiding place to avoid being eaten by other animals, and something to eat themselves. It’s as simple as that. There’s absolutely no reason why that pond can’t look attractive to human eyes too, and there is no reason for a wildlife pond to have to look scruffy.

Formal symmetrical design.

Natural swimming pond.

A wildlife pond.

An ornamental pond.

Small wildlife pond.

Attractive wildlife pond.

Having said that, the most diverse habitat is created by maximising the number of niches in which animals and plants can live, so an operating theatre mentality is to be avoided in favour of a managed degree of ‘LIA’ – Leave It Alone. An occasional clear-up will be necessary to remove excess organic material from the pond, but a tangle of old stems is a valuable place for many insects and amphibians to lay their eggs, so don’t be too quick to tidy up those fallen stems until after all the critters have completed their breeding cycle.

If you wish to maximise the appeal of the pond for wildlife, there are three important things to remember before you start:

1. Access

Animals need a safe route to get in and out of the water, so the pond should be linked by a wildlife-friendly corridor to the rest of the surroundings. The best way to ensure that is to link the pond vegetation with planted areas outside the pond, linking further to the wilder areas of the garden. A pond which is completely surrounded by paving or other hard landscaping for design purposes is less likely to attract shy wildlife. A carefully thought-out edge detail will allow easy ingress and egress (more on this later).

Wildlife corridor.

2. Fish

Fish do not exist in tiny natural bodies of water (which are rare in themselves) because the habitat is too small to support them. Therefore, fish are not appropriate in small wildlife ponds. Once a pond gets over about 100m2, it can support a small number of tiny fish such as sticklebacks or minnows, which are not at the top of the food chain themselves but actually prey items for some of the bigger insects, like dragonfly larvae and diving beetles. If you can’t live without a couple of goldfish then by all means introduce them; just remember that they will eat a high proportion of all the damselfly eggs and tadpoles and you will therefore see far fewer froglets and beautiful insects. It’s your pond, and at the end of the day, your choice.

Formal white pond.

3. Sun

Insects are cold-blooded and to some degree require the heat of the sun to enable them to get airborne. Flowers that have evolved to attract insects to pollinate them mostly grow best in the sun. Therefore, a successful wildlife pond will be best situated in a mostly sunny location. (See ‘The Paradox of Shade’ below.) Nearly all of the action takes place in the warmest and shallowest areas and excessive depth is unnecessary – even in the worst UK winter it is unlikely that there will be more than 15cm of ice, so a depth of 60cm is more than adequate to protect wildlife from freezing.

Open, sunny location.

PLANNING AND POSITIONING

It’s really important to make a plan, and the bigger the pond is, the more detailed the plan will need to be. In the case of larger ponds requiring machine digging, a proper land survey is to be recommended.

Poor design has led to too much liner showing.

While you’re at the planning stage, bear in mind that most pond liners come in widths in multiples of 0.6m, so sometimes it’s worth considering planning the exact pond dimensions around the liner width possibilities, rather than the other way round. Sometimes people wildly overestimate the size of liner required, ending up with a huge and probably useless offcut that looks like a map of Norway. You do need to allow at least 15cm overlap all around, but you don’t need to waste a metre all round.

Basic sketch plan.

For ponds less than one or two cubic metres a simple sketch is probably all that is necessary but do think carefully about what you will do with the excavated material. Please don’t dump all the subsoil right next to the pond, stick a couple of modest sized stones in it and call it a rockery. Nothing will grow well in it, and it will look like exactly what it is. If you don’t need the material to fill holes elsewhere then it is preferable to get a skip and have it removed. It may be annoying that this will be one of the biggest costs, but it will be the best thing you could do. With medium to large garden ponds the cost of spoil removal can start to get worrying, so by all means consider if you are able to ‘lose’ some of the spoil somewhere else on the site. The best way to do this is to identify an area that could be raised without causing problems, strip back the topsoil, tip and spread the unwanted subsoil and then spread the original topsoil back on top.

Avoid cut and fill in favour of excavate and remove.

One issue affecting most ponds is that of windblown leaves and waterborne soil and debris. It’s really important to minimise the amount of organic material and soil finding its way into your pond, as this is what causes algal blooms and problems with blanket weed and duckweed. If possible, ensure that the pond is on the south to southeast side of any tall walls, fences or trees to maximise the amount of sunlight available. Don’t locate the pond under or just downwind of large trees or shrubs, and don’t necessarily locate it in the lowest lying part of the garden, to prevent heavy rain from washing soil from the paths and borders into the pond. Ideally, the pond should be in the sun for most of the day and should be somewhere where it can be enjoyed.

The orientation of the pond is of little consequence and is best planned to suit the space in which it sits. Do, however, give full consideration from the point of view of the wildlife that you hope will make use of the pond.

Drawing a plan

At the very least it is worth preparing a scaled plan and section of the area, not forgetting to include the area immediately around the pond and how it will integrate with the rest of the garden. Do keep one copy without scribbles and annotations so you can use it as a master, producing as many copies for changes as are necessary. Use marker spray to mark the outline and check that it looks right before ever putting a spade in the ground. It’s much easier to kick over an old marked line and redraw it than replace soil already dug out – it never goes back as firmly as before.

Making the pond look natural

The most natural looking ponds are created by excavating out of the existing landscape, removing all the spoil, not cutting and filling, which is the easiest and cheapest solution (see also Chapter 4). On more steeply sloping sites one needs to consider the topography very carefully. One thing to try to avoid is to create a berm or bank on the downhill side of the pond. This will make the pond look unnatural and out of place, like a reservoir. Natural ponds don’t form on the side of a hill with a retaining bank on the downhill side, and it will show. You will also probably end up with an awkward bank and probably a steep slope to manage, and settlement or erosion issues can result. Additionally, if the topsoil is not stripped off the site where the bank resides before the material is tipped there, it creates a layer which is very vulnerable to leaking. If a liner is used, then this is not an issue.

The paradox of shade

While surface cover in a pond is vital to prevent sunlight from causing excessive algal growth, this shade should be provided by the pond plants themselves, not by trees or shrubs outside of the pond. Most pond plants, especially those with coloured flowers, require plenty of sun in order to flower well. The coloured flowers evolved to attract insects, and most insects need warmth and sun to be able to fly, as they are cold-blooded. Shady ponds full of leaves are very poor for wildlife and offer few planting options.

GROUND CONDITIONS

If your pond is in a low-lying part of the garden, or if there is a high water table in winter, remember Archimedes – water pressure from underneath the pond can cause ‘hippos’ in the liner; these can be difficult to deal with and can cause disruption to planted baskets on top. This can cause big problems with geotextile liners, which are extremely heavy and rely on tight joints filled with bentonite clay for their waterproofing. If these joints are opened up by pressure from below, they may not seal properly when the ground water subsides and will probably leak thereafter. This is a very difficult thing to fix, so consider a necklace of land drains under the liner to prevent it. It is even possible for preformed ponds to lift out of the soil if they are not full to the brim.

Making a small dam

If a stream runs through the area where your pond is to be made, even if the stream rises on your land, you may require water authority consent in the form of an abstraction and/or discharge licence. Damming a stream to create a pond is highly inadvisable in any case. It is highly recommended that you construct the pond to one side of the existing stream, or if not, construct a bypass channel to allow the whole spate flow of the stream to run around the outside of the pond while drawing off the bare minimum to keep the pond topped up. If you don’t, you will find that the pond fills up with silt and debris extremely quickly, and the regular job of removing all this is likely to cost more than the original construction, not to mention the question of what you will do with it all. The amount of material carried by even a small watercourse during a flood is unbelievable, and it is much better for you if it roars all around your pond and becomes a nuisance to someone else downstream. Frequently one sees advice to make a silt trap on the upstream side and clear it occasionally, but unless you fancy clearing it out daily in winter it will be utterly futile, since it will most likely fill up the first time the stream is in spate, and thereafter it will be useless. Ideally, cut off the stream flow completely in winter at point A, and only divert sufficient water to maintain pond level in summer. A permanent through flow is not necessary.

Create a bypass to avoid silting up of the pond.

BUDGET

If you’re planning a tiny or small pond, the budget is probably not the most important factor, but as the size increases and the range of variables expands, it is most definitely worth establishing what it will all cost before you start. It’s very tempting to make the pond as large as you can, but then as the costs mount up there is a real risk that compromises will be made at the end, leading to an unsatisfactory result. As a result of internet competition, many of the materials that you will need are similarly priced from many sources and can be costed with great accuracy. At the time of writing, a good quality pond liner costs in the region of £8 per square metre and top-quality underlay about half of that, so the two main ingredients needed for most garden ponds together cost £12 per square metre. A typical garden pond 60cm deep and measuring 4m by 2.5m can therefore be lined for around £300. It will quite likely cost you more to get rid of the unwanted subsoil than to buy the liner and underlay, so to my mind it simply isn’t worth trying to reduce that modest cost by using lower quality materials. The internet forums are full of cheapskate fools using builders’ plastic and old carpet, but this approach can easily lead to disappointment. If you’re going to do it, better to do it once and do it properly. More detailed information will be found in later chapters.

WHO WILL DO THE JOB?

The next thing you are going to have to decide is whether you aim to complete the job yourself, or with help, or whether you are going to get someone else to do it for you. This is probably the single most important decision you will make in the course of the project, and it is important to get it right. Again, for tiny or small ponds there is little doubt that you will have a good idea of what you want and how you wish to go about it and will probably do it all yourself. A fit person can easily dig out a cubic metre or two of soil in a day by hand in average soil conditions, but if there are old tree stumps to remove or if the ground conditions are challenging it is very hard work indeed. Why not invite some friends around; with sufficient beer and barbecue sausages on hand it is surprising what can be done. Beyond a certain point it is likely that you will be considering using powered machinery such as a mini digger, in which case you need to work out how to get it to where it is needed and how you will move the soil being excavated. Small machines that can access back gardens via a gate or doorway have a very limited reach, so the digging must be carefully planned to avoid ‘painting yourself into a corner’. Mini diggers can be hired with or without an operator, and if you have not used one before I strongly recommend that you do the former. Achieving a professional result is not at all easy the first time, especially on a sloping site.

Larger projects

It is perfectly possible to move mountains with hand tools and a great deal of time and effort, but for larger ponds, machinery is a must in most cases. In more restricted locations a mini excavator and wheeled or tracked power barrow or dumper is the most likely combination, but for larger and more accessible sites sometimes a wheeled digger is more versatile. Many operators are used to working mainly on construction sites in a sea of mud and may not appreciate that you don’t want your garden to look like the Somme, so it’s really important to establish whether your chosen contractor has carried out such work before, and to visit and speak to a recent customer to find out if their experience was good.

Heavy liners need a big machine to handle them.

If you are going to be using a geotextile liner, then you may need a much bigger machine to handle the heavy rolls than you actually need for the excavation. It is vital if you are using any kind of contractor that you create a proper detailed specification, with sections and plans and a clear explanation of who is to do what. Make absolutely sure that they understand the edge detailing, as this is critical, and so often the one thing that lets down an otherwise well-executed plan.

The gold-plated solution is to employ a pond services company who specialise in this kind of work. If they have been in business for some time, they will have come across all the problems before and will have well-rehearsed solutions. The whole job may even cost less in the end due to their specialist sourcing knowledge and the avoidance of expensive mistakes.

Employing contractors

Do vet the operator carefully before taking them on, since all some machine drivers want to do is to dig as deep as possible, as steep as possible and as quickly as possible. You need to have someone who is going to listen to what you want, take it slowly and steadily, and not over-dig or get carried away. Edge profiling is absolutely critical, and I will return to this topic many times. Once soil has been excavated it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to put it back without risking it slumping or crumbling afterwards, so as you get close to the required depth and profile it is often a good idea to revert to hand tools to get it just right. Once the digger driver starts work, don’t leave them for a second, and if you have to leave even briefly, insist that they stop work until you get back. Don’t say I didn’t warn you!

LINER AND WATERPROOFING OPTIONS

In theory there are many possible lining solutions, but generally these will be determined by the size of the pond. All have their advantages and disadvantages, but the size of the pond will eliminate or favour certain solutions. Liners can be ‘passive’, which means that they are guaranteed to work straight out of the box, or ‘active’, relying on a hydration process to work.

The most commonly used liners are:

• Rigid preformed plastic or GRP (glass reinforced plastic or fibreglass) liners.

• Flexible membranes of reinforced polyethylene (RPE), PVC, butyl rubber or EPDM (Ethylene, Propylene, Diene Monomer) rubber.

• Concrete or masonry, often rendered with sand and cement and sealed with one or more coats of a liquid sealant such as G4 or glass reinforced plastic (GRP).

• Puddled or compacted clay layers with or without added bentonite granules.

• Geosynthetic clay liners (GCLs): these comprise multiple fabric layers incorporating bentonite clay, and subsequently covered with a lightly compacted layer of soil; the liner expands on contact with water and forms a seal that is to some extent self-healing.

For very small ponds there will usually be a straight choice between a rigid preformed liner or vessel and a rubber or plastic sheet liner.

Rigid preformed liners

Rigid preformed liners made from plastic or fibreglass (GRP) are widely available, but many suffer from a lack of suitably sized and positioned planting shelves. The larger sizes are relatively expensive and unwieldy to handle. They are also quite tricky to install neatly and require a lot of careful hole sculpting and sand infill to make them level and solid. Small sizes are not as easy to use for raised ponds since the edges are insufficiently strong to support them when full; they must be evenly supported over the whole outer surface. They don’t have any overriding advantages but could be a good choice for very small ponds.

Pre-formed pond liners frequently have pathetic shelves.

Sheet type liners

Sheet type liners can be made in a variety of materials listed previously, and are extremely versatile, being the de facto choice for most garden ponds. Pre-packed and off the shelf liners tend to go up to 10m width and a standard full roll is 30m long. Widths tend to increase in increments of 0.6m, so there is no need to have too much waste. Allow an extra 15–30cm all round to facilitate installation; more than this is likely to be wasted. Larger sizes to about 60 x 30m can be made to order, but larger liners than that must be welded on site.

Cheaper liners are available in various recipes and thicknesses of polyethylene and PVC, some reinforced with fibres and some not; unsurprisingly, you get what you pay for. They are frequently guaranteed for a certain number of years, often fifteen, so they are perfectly adequate in most cases. Builders’ plastic is unsuitable, ever, as it will very soon crack and split when exposed to the sun. So, if your budget is restricted (and whose isn’t?) or know that for some reason your pond will have a limited lifespan, the less expensive liners can be a valid option. In terms of cost saving alone though, it’s hard to justify, given that the cost of a top-quality liner is still only a small fraction of the cost of the completed job. Sheet liners are therefore affordable, easy to handle and can be installed by anyone with half a brain who is prepared to take a little care.

EPDM rubber and butyl rubber

The most popular choice at the time of writing is EPDM rubber. This is a similar material to that used for tyre inner tubes: it is tough, flexible and versatile and well worth the premium price. Butyl rubber is