Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Salt Modern Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

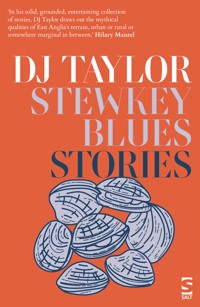

On Stewkey Blues: 'In his solid, grounded, entertaining collection of stories, DJ Taylor draws out the mythical qualities of East Anglia's terrain, urban or rural or somewhere marginal in between.' —Hillary Mantel Most of the people in Poppyland are watching their lives begin to blur at the margins. From small-hours taxi offices, out-of-season holiday estates and flyblown market stalls, they sit observing an environment that seems to be moving steadily out of kilter, struggling to find agency, making compromises with a world that threatens to undermine them, and sometimes - but only sometimes – taking a decisive step that will change their destinies.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

DJ TAYLOR

POPPYLAND

iv

v

Their beauty has thickened.

Something is pushing them

To the side of their own lives.

philip larkin, ‘Afternoons’

Dave, Rodney, Stevie, Spike, Eddie, Horace, Richard, Shaun and all the other Norwich boys

vi

Contents

Poppyland

They came down the winding asphalt path from the cliff-top in their usual holiday phalanx: Danny in front, guiding the buggy; Marigold a step or two behind him; Mr and Mrs Callingham vigilant on the flanks. At the bottom of the slope there were a couple of herring gulls tearing open an abandoned fish-and-chip packet, but the sight of Mrs Callingham in her saffron summer frock was too much for them and they flapped noisily away. Bird, Archie chirruped from the buggy – it was one of the five words he knew, along with ‘bean,’ ‘bath-time,’ ‘banana,’ and ‘Ummagumma,’ his pet monkey – bird, bird, bird, bird, and Danny leant forward and patted him fondly on the head. The herring gulls were gone now, heading out over the pier into the duck-egg-blue sky, bound for the Hook of Holland for all anyone knew. Bird Archie said one last time and then went silent. Down at the foot of the cliffs it was unexpectedly cold and the shadow cast by the hand-rails fell dramatically across the pavement. Danny, bringing the buggy to a halt, glanced surreptitiously at the figures assembled around it: Marigold, dutifully attentive 2to whatever her mother was saying; Mrs Callingham, blithe, stork-like and terrifying; Mr Callingham a more solid presence, but, Danny knew, liable to cause trouble if not closely watched.

‘Well, this is all very picturesque,’ Mrs Callingham said, propping one of her huge bony knees upon the bottom-most rail. Unlike many of Mrs Callingham’s opinions this one, Danny acknowledged, had something to be said for it. The steps running up to the pier entrance had panels sunk into them which recorded the exploits of the Cromer Lifeboat. On the wall beyond hung posters of Freddie Starr, the Nolan Sisters and other veteran acts who were appearing in Summer Season. It was about ten o’clock in the morning, still early for the holiday crowds, and not bad for mid-July. ‘I used to come here as a boy,’ he began to explain, feeling unexpectedly proprietorial about the row of beach huts and the criss-cross of anglers’ lines, but Mrs Callingham was not in the mood for childhood reminiscences. ‘I had a long conversation with Fenny,’ she said, addressing herself to Marigold, ‘and she had some good news and some bad news. The bad news is that Angelica has failed her driving test, but the good news is that Mark’s psoriasis is improving.’ Defying the urge to add ‘as if anyone cared,’ Danny looked to see how his father-in-law was taking this update on his wife’s sister’s family, but Mr Callingham, who had not yet found a newsagent able to sell him a copy of The Times, was still sunk in gloom.

‘That’s a shame about Angelica,’ Marigold said absently. She was still exhausted from the previous afternoon’s three-hour drive and the sleepless night with Archie. Another day or so and she would be able to give these 3Clan Callingham gossip-fests all the punctilious gusto they deserved. The Callinghams, who answered to ‘Billa’ and ‘Geoffrey’, were reaching the end of their stratospherically distinguished careers. Billa taught medieval history at one of the smaller Cambridge colleges and had written a ‘seminal’ book about Angevin Shropshire, while Geoffrey did something so mercurially abstruse at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office that Danny had never actually managed to work out what it was. Four years on, he was still amazed that they had allowed him to marry their daughter. ‘Of course,’ Mrs Callingham was saying, with a certain amount of bitterness and in a blizzard of phantom italics, ‘it’ll be a great advantage when she does pass her test because I dare say she’ll be able to drive down and visit you.’ And Danny knew that they were back to the conversation that had enlivened, or strictly speaking undermined yesterday’s trip along the A12. ‘Oh, Mum,’ Marigold said, ‘it’s only something we’re talking about. Something to discuss.’ There were times when he thought the Callinghams were a well-meaning but censorious and interfering old couple and other times when he thought the four of them were engaged in a no-holds-barred power-struggle that made the Wars of the Roses – about which Mrs Callingham had written illuminatingly – look tame by comparison. Desperate for a diversionary tactic, he tapped Archie on the shoulder with sufficient heft to make him swivel slightly in his seat and then said with apparent surprise: ‘You know, I think Arch has another tooth coming through.’ This did the trick. Mrs Callingham, whose attitude to children was that of Grace Darling towards water-boatmen, went down on one knee and grabbed at Archie’s face between her 4coal-heaver’s fingers. ‘Poor ickle babbity,’ she pronounced, with no self-consciousness whatever. ‘Is oo’s toofy-pegs hurting um?’ Naughty toofy-pegs.’ Amid the clamour of the gulls and the roar of the water crashing against the sea-defences, tiny, insignificant figures dwarfed by the wide horizon, they made their way down to the beach.

After that things improved slightly. Mr Callingham found a kiosk on the front that sold newspapers and settled down to read about the war in Iraq. Mrs Callingham ate an ice-cream in a mincing, girlish way and gave exaggerated little shrieks of disquiet as fragments of the chocolate flake tumbled down the front of her dress. Marigold unfurled a towel on the sand, lay down on it and fell instantly asleep. Archie, unleashed from his buggy, tottered a few steps here and there, collapsed in a tumble of misplaced limbs, tried to eat a worm-cast and said a sixth word, which might have been ‘Diogenes.’ Still, though, danger lurked in all this seemly repose. Mrs Callingham relayed some more urgent family news about someone called Francesca, who might or might not have been sent to Indonesia by whoever it was that employed her, before offering some startlingly unoriginal remarks about the Government’s education policy. Mr Callingham, benign and rubicund in open-toed sandals and rolled-up flannel trousers, got as far as the Arts pages of The Times and then gave an ominous snuffle. ‘There’s a man here really doesn’t like your book,’ he declared.

This kind of thing had happened before. With infinite weariness – not because he feared the reviewer’s strictures, but because he feared the conversation that would follow his reading of them – Danny lent forward, discovered 5that for some reason Mr Callingham was not prepared to relax his grip on the paper, but eventually gathered from glancing over his shoulder that Daniel Foxley’s third novel was an undistinguished performance that harboured few of the qualities intermittently on display in its predecessors. ‘Friend of yours, is he, this I. B. Littlejohn?’ Mr Callingham wondered in a half-way jovial tone, and Danny smiled back. ‘We were at college together,’ he riposted, and then, for good measure, ‘He taught me all I know.’ Mrs Callingham was having one of her vague moments, when the warp and weft of the world escaped her usually circumspect eye, but in the end Mr Callingham managed to explain to her what had happened, and she, too, was allowed a grudging glance at The Times. ‘You really are not to worry about this,’ she instructed him. Mrs Callingham’s attitude to Danny oscillated wildly. Early on in their relationship she had told Marigold, not wholly approvingly, that he was ‘rather a high-flier.’ Just lately she had been heard to say that these provincial universities were making great strides. ‘When we get home,’ she said fiercely, as if someone were purposely delaying her journey there, ‘I’ll make us all lunch. That is, if one can find a serviceable saucepan.’ After that they sat there in silence under the wide sky, while children shrieked and cantered around them, until such time as Marigold woke up and they could collect their things, find the car and drive off through the Norfolk back-lanes, the head-high clumps of cow parsley and the shimmering fields of poppies.

◊

6The holiday let was three miles out of Cromer at the end of a lane of beech trees: elegant, spacious, cool even in summer. Mrs Callingham’s way of finding fault with it was to go fossicking around the kitchen drawers lamenting the absence of items no ordinary person could ever want: an egg-whisk and a cake-knife were high on this list of desiderata. Danny knew already that the visitor’s book, which lay on the hall table next to a Bakelite telephone and a gazetteer called What to do on the Norfolk Coast, would not be safe from her. For lunch Mrs Callingham cooked an Irish Stew, heavy on the onions and with additional clumps of pearl barley lurking in its lower depths. In the intervals of eating it, and trying to interest Archie in a warmed-up jar of savoury rice, and watching the Callinghams absently-mindedly clash water-glasses together and knock over salt-cellars, Danny found himself wondering, as he quite often did, what kind of people they were. When first ushered into their presence in the big, cacophonous house at Harrow-on-the-Hill, he had assumed that they were old-fashioned, high-minded liberals of the sort he had read about in books about the Bloomsbury Group, only to discover that Mr Callingham, at least, quite liked talking about money and reading the How to Spend It section of the Financial Times. ‘My mother is a very straightforward person,’ Marigold used to maintain, which was true in one way and so transparently false in another as to make you wonder whether her occasional bouts of plain-speaking weren’t an elaborate smokescreen thrown up to disguise the extraordinarily complex mixture of will-power, abstraction and downright craziness by which Mrs Callingham lived her life. In the end he decided that the Callinghams, 7Billa and Geoff, Professor Wilhelmina Callingham PhD., F.R.H.S, and Geoffrey Callingham OBE, were simply two wonderfully eccentric and self-propelled people whom chance had thrown together and sent spinning forward while the rest of humanity cowered in their wake, that they would offer marvellous parts for someone to play in a film but were rather less appetising when you had to live cheek-by-jowl with them for weeks at a stretch.

‘You would think that this place would run to a ladle,’ Mrs Callingham complained, dumping another pile of onions on Danny’s plate. After lunch, knowing what he was letting himself in for but determined to do his best, he volunteered for the washing-up and dealt politely with the imperfectly-rinsed cutlery while Mrs Callingham talked about some friends of hers who had moved to Lincolnshire and really lost touch and how very susceptible certain parts of the South-west were to flooding – further oblique references, as he well knew, to the conversation of the previous day. Archie, returned to his buggy, had fallen asleep. Mr Callingham, now barefoot and be-shorted, sat watching cricket on the TV. Leaving Billa with a book called Planning for Dystopia, he went into their bedroom and found Marigold stretched out on the bed with her arms and legs extended in the shape of a Maltese Cross.

‘How was the washing-up?’

‘It was a blast. I put all the forks in the fork compartment and all the knives in the knife compartment and then your mother came and mixed them up again. After that she started telling me about some friends of hers who moved out of London and they ended up feeling so isolated that the husband went mad and tried to shoot himself. Oh, 8and how wonderful she thinks Arch’s day-nursery is and how nice all the girls who work there are.’

‘You can hardly blame her for that. Not after Etta and Sophie. We’re the only ones left in town.’

It would have been wrong, Danny knew, to tell Marigold that there was a reason why one of her sisters lived in Newcastle and the other in North Wales, so he smiled in what he thought was a sympathetic way.

‘Did you ring work?’

‘No I didn’t.’ Marigold did the marketing for a high-end stationery concern that sold monogrammed notepaper and envelopes in a variety of aquarelle washes. ‘I left instructions for the press release to be sent out on Thursday, and if anybody rings up Rebecca will just have to deal with it herself.’ She chewed at her lower lip in a way he always found irresistible. ‘How do you think Dad is?’

There was no way of honestly answering most of the questions Marigold asked about her parents. How did he think Geoffrey was? Slightly more pompous and slightly less affable than usual? Far too fat? It was difficult to tell.

‘Seemed on good form. He was wearing a pair of shorts last time I looked. Really getting into the spirit of the afternoon.’

This kind of bantering never worked with Marigold. She was a serious girl, and never more so than when the talk turned to members of her family and how they were feeling about things.

‘Mum says he’s a bit worried. Apparently someone’s been complaining about a treaty he helped draft for the Turks and Caicos Islands back in the 1980s. Something to do with not apportioning mineral rights.’ 9

Danny had a sudden vision of vengeful islanders denied their cobalt and lithium dancing upon the Caribbean strand as they burned Geoffrey in effigy. But it did not do to dwell on these things. What he really wanted, he thought, was to take Archie for a walk through the poppy fields, far away from Geoffrey in his horrible shorts and the look of savage exaltation on Billa’s face as she dropped the cutlery into the wrong compartment.

‘If we did decide to go and live there,’ Marigold said, suddenly brisk and purposeful, face aglow under her thatch of blonde curls, ‘What am I supposed to do?’

‘Well you wouldn’t have to sit there listening to Rebecca drone on about the Duchess of York. And you know you’ve always said you wanted to set up on your own.’ Marigold bent her head, which was a start, but he knew that this was not what the conversation was really about. ‘Look,’ he said, knowing that he was overplaying his hand, ‘you can’t spend your whole life conciliating your mother.’

‘But that’s what you have to do, isn’t it?’ Marigold said, not exactly miserably but with considerably more emphasis than she put into most statements about human behaviour. ‘You conciliate people and you put up with them, because of what you owe them.’ Beyond the door he could hear Archie emit one of those little yells that meant he was tired of listening to Billa asking him if he had enjoyed his ickle sleepie or having her wave brightly-coloured lengths of silk above his head. ‘Do you know Etta says she rings them three times a week? And she’s offered to pay all Ceridwen’s nursery fees.’

There was no gainsaying this, Danny thought. Maternal affection was sacrosanct. All the same, it made you want to 10enumerate some of the things that putting up with people entailed. In his own particular case it meant having them come on holiday with you and severely limiting your room for manoeuvre while they were there. It meant them giving your children ridiculous nicknames – Billa had started off trying to call Archie ‘Archers’ before settling on ‘Arch-Warch’ – while not registering the pained look on your face. It meant being subjected to a constant barrage of information about distant relatives you might have met at your wedding but would never see again. It also involved – and this, too, had to be allowed – being thoroughly exasperated by people who meant well while remaining heroically unaware of the annoyance they were causing.

‘We ought to go and see how Archie is,’ Marigold said, and then, just to make sure that he knew she was still in a bad mood, ‘Gosh I’m tired.’

They went into the main room to find Archie staring grimly at a pile of Lego bricks, Geoffrey still watching the cricket and Mrs Callingham collapsed into a cane chair with the peculiarly glazed and stricken expression that he remembered from previous holidays. Billa’s headaches were not to be trifled with. Genuinely sympathetic, for once, Danny brewed tea, fetched glasses of water and hunted out Ibuprofen capsules from the vast pharmacopeia Marigold had brought with them. Separating out the emotions that these acts bred up in him, he realised that he was pleased with himself for the show of willing, cross with himself for permitting an unwonted level of self-congratulation, contemptuous of anyone who succumbed to anything so trivial as a headache and disgusted with himself for his lack of fellow-feeling, while darkly aware that all this 11complexity was part and parcel of what life with the Callinghams was like, as soul-sapping and ineradicable as all the plastic micro-globules strewing the ocean floor. Bird-bird-bird-bird-bird Archie carolled, who had presumably glimpsed one outside the window, ‘Has ‘oo seen an ickle birdie, den?’ Mrs Callingham began, but then gave up the struggle and held her head in her hands. Outside the sunshine fell over the bright green grass.

◊

Slowly the long days passed. Sometimes they headed north along the coast. Other times they went inland in search of supermarkets or places where Mr Callingham could buy the New Statesman. They went to Holkham, looked around the park and listened to Mrs Callingham criticise some of the portrait attributions. They attended art exhibitions in village halls set back from the coast road, examined the pictures of crab-boats in Blakeney harbour or terns taking flight off Stewkey marshes and drank cups of pale tea from urns drawn up on rickety trestle tables. They went to the Smoke House at Cley and stocked up on pickled herrings and jars of anchovies. Occasionally the old world they had left behind intruded. It turned out that the girl who had been supposed to send out the press releases had gone home sick before she had had time to do it, and Marigold had to spend an hour on the phone repairing the damage. A newspaper rang up and asked Danny for a comment piece about some pictures of Madonna at the gym (‘Interesting things you get to write about,’ Mr Callingham observed when it was shown to him the following 12morning.) There was another, better review of Danny’s novel in the Daily Telegraph (‘Isn’t he a friend of yours too?’ Mr Callingham wondered.) Mr Callingham had cheered up a bit and seemed to have forgotten about the Turks and Caicos mineral rights.

Formula milk heated up in a plastic bowl. Baby rice. Calpol. Teething rusks. Tumbled Lego bricks. ‘Gosh I’m tired.’ Sometimes the routines they had spent so long devising fell away and new patterns emerged. Out walking the back-lanes or striding inland through the waist-high grass, the old phalanx was abandoned and they marched in single file, Mrs Callingham prospecting along the path and talking to Marigold over her shoulder. Wondering whether he was supposed to hear the gusts of conversation which rattled back and forth, some of which were surprisingly intimate and several of which concerned himself, Danny decided that it had simply not occurred to Mrs Callingham that he might be within earshot. She was famous in Cambridge circles for once having given her opinion of one student to a second student without realising that the first one was seated next to her on the sofa. Still, it was nice to know that the mother of the woman you were married to reckoned you fundamentally good-hearted if prone to hasty decision-making. But how would he have fared on that college sofa? Danny trembled to think.

Ironically, in the light of what came after, the trip to Ranworth, half-way through the second week, was Mrs Callingham’s idea. It was she who turned out to have mugged up on the Broads, and she who had identified the great tall church with its view out over the Norfolk flats 13as worth an hour or two of their time. They took a packed lunch, set off early along the coast road through the tourist traffic and the hopper buses and then cut inland through the reed-beds. Banana Archie sang. Banana, banana. There had been another urgent colloquy about their relocation the previous evening. In its bruising aftermath Danny couldn’t quite tell if he was wearing the opposition down or being worn down himself. One good omen, he supposed, was that Marigold, telephoned at 8 p.m. by the Duchess of York-toadying Rebecca, had actually put the receiver down on her. Fetched up at the church, with its soaring flint tower and the mass of dark water stretching away into the middle distance, he was surprised at how small everyone seemed. Mrs Callingham, unloading cagoules from the back of the car, looked a frail and insubstantial figure, there on sufferance, ripe to be swept away. Archie, asleep in his buggy as the dragonflies swarmed over his head, was a tiny embellishment on the edge of the frame. Downcast by this hint of his own insignificance, Danny pressed on into the church’s interior, which was cool and dim and there was a smell of furniture polish. He liked churches and found their atmosphere consoling. Mrs Callingham, too, was manifestly enjoying herself. She found a pile of prayer-kneelers that had slipped out of trim and zealously restored them to order, and then sped down the aisle casting indulgent glances at the carved pew-ends. A bit later her eye fell on the doorway that allowed access to the tower.

‘Shall we ascend?’ she wondered in the faultless parody of a Victorian noblewoman that she sometimes affected on special occasions.

‘Well, I’m keeping my feet on the ground,’ Mr 14Callingham volunteered, tapping the rim of the buggy with a fat hand. ‘Someone’s got to look after His Lordship here.’

‘There’s a hundred steps, Mum,’ Marigold said, who had also read the guidebook. ‘And then a couple of ladders before you get to the roof. Are you sure you wouldn’t be better off staying here?’

‘It will be an adventure,’ Mrs Callingham said, reprising the girlish glee with which she had eaten the ice-cream cone.

And so they set off, Danny leading the way, Mrs Callingham following, Marigold bringing up the rear. The church was silent except for the slither of their footsteps and, from below, a faint growling noise which Danny supposed was Mr Callingham trying to entertain his grandson. The staircase was circular and rose sharply. Danny put on speed and came out on a wooden platform that contained the church bells and the first of the two ladders, stopped for a second or two to catch his breath and then pressed on to the roof. There was no sound coming from below so he went forward to the parapet, laid his arms lengthways on the stone and gazed out over the broad, where boats were tacking back and forth in the breeze and what looked like a kayak race was in progress in the corner. On the far shore the woods sloped down to the water’s edge and it needed only a couple of greybeards stretched out under a tree and a glimpse of a ruined temple to make you think you were in a painting by Claude Lorrain.

‘Danny, you’d better come down,’ Marigold said anxiously as she came out onto the roof to join him.

‘Why’s that?’ 15

‘It’s Mum. She’s stopped three quarters of the way up. She says she can’t go on anymore.’

‘Well, tell her to go back down.’ He was still cross about the vision of Claude Lorrain being prised from his grasp.

‘It’s not as simple as that. She says she’s stuck. She’s always had this thing about heights. You know, freezes up and can’t move.’

‘How did you get past her then?’ He was quite interested in this as a scientific problem. ‘I mean, if she’s stuck fast?’

They hurried back down the ladder, bounded over the belfry platform and rapidly negotiated the steps. At head level there was ancient graffiti carved into the brickwork that said GWD and EY had been here in 1894, and he wondered what sort of time they’d had. Mrs Callingham had come to rest next to a tiny niche in the wall, one arm angled slightly forward from her body and the other angled slightly back, as if she were frozen in the act of running, and he stopped abruptly and sized her up.

‘What’s the matter, Billa?’

‘It’s very stupid of me,’ Mrs Callingham said almost skittishly, ‘but I just can’t move.’

‘Well, you can’t stay here. Are you able to turn round?’

‘No, I’m not. It would be all right if I wasn’t in this enclosed space,’ Mrs Callingham explained, as if it had been very stupid of whoever had designed the tower not to have realised that she might want to climb up it several hundred years later.

‘Well, you’ll just have to come down backwards.’ He managed to squeeze past, coax Mrs Callingham onto the steps, grasp one of her hands and tug her into reverse. ‘Be 16careful,’ Marigold cried from three steps above. ‘Really, I’m quite all right,’ Mrs Callingham said. The process of extracting her took half an hour. At the bottom of the stairs they found several people waiting to go up. ‘I’m very sorry to have delayed you all,’ Mrs Callingham said brightly, before unexpectedly bursting into tears.

◊

All that last morning at the house, as Mr Callingham harumphed about and Marigold turned up items of baby equipment in odd places, he found himself wondering what Mrs Callingham would write in the visitor’s book. Would she complain about the paucity of casserole dishes? The noise the cistern in the upstairs loo made when you flushed it? The way the overgrown honeysuckle clanged against the downstairs window when the breeze got up? These were all plausible candidates. In the end, though, picking up the book when her gaze was elsewhere, he discovered she had written only that the Callingham/Foxley party had enjoyed a very pleasant stay in a well-appointed holiday home and might easily return one day. If this was a small victory, then a larger one had manifested itself on the previous evening when Mrs Callingham had conceded that bringing up a young family in London didn’t suit everyone and that Marigold was looking rather tired these days.

Still, though, you needed to be sure. He knew from bitter experience that where the Callinghams were concerned, nothing could ever be taken for granted. They had almost finished loading up the car – Billa and Geoffrey in the back on either side of the baby seat, Archie with 17Ummagumma dangling from the fingers of one hand, the tea-towels and recipe books they had bought in stately homes along the way parcelled up in the glove-compartment – when Mr Callingham, who had an OS map of East Anglia open on his knee, said: ‘If I were you I’d head for Lowestoft and take the A12.’

‘Actually,’ Danny said, keen to press home his advantage, ‘I thought the A11 would be a better bet.’

A bit later they set off along the beech avenue, where glimmers of yellow light broke through the tree canopy and the squirrels sat motionless in the branches as if they had never seen a car before and wondered what horrors it might portend, and then off through the wheat-fields, where the poppies, crimson and consoling, shimmered at their side.

Moving On

Kev and Chrissie get the keys to 18 Hodgson Road, Norwich in January 1983. Kev is nineteen and Chrissie a year younger, but there is a marriage certificate behind the clock on the mantelpiece in the front room where Chrissie also keeps the rent book and the passport that accompanied her on a day-trip to Boulogne four years back, and Kev’s Aunty Sheila, who has influence in these matters, has put in a word at the City Council Housing Department. Aunty Sheila has been renting council houses all over the west side of Norwich for thirty years and knows what to do. She is a big, shapeless woman – twice the size of Kev’s diminutive mum – who runs a fruit and veg stall on Norwich market. Kev says the house is a good place to start off – handy for Bunnett Square and its double row of shops and at the end of a bus-route that will take Kev to his job, which is at the Jarrold print works in town. Among other items, Jarrold’s manufactures picture-postcards of Norfolk scenes: Yarmouth seafront; Holkham beach; Thetford Forest. Sometimes Kev brings a pile of them home in his knapsack and they use them for shopping-lists. Looking out into the back garden on winter afternoons – it is mostly 19concrete terrace, but there is a patch of grass and a plastic swing that the last tenants left behind – Chrissie thinks the house will do. She is a pale, serious girl with two ‘O’ levels (English Literature, Home Economics) and a tendency to asthma. Kev has no qualifications, unless you count the St John’s Ambulance Brigade certificate that he acquired in the Boy Scouts.

Somehow Kev and Chrissie never settle at No. 18. The house smells of damp, there are rats in the walls and the Brannigans, who live next door, have a habit of throwing parties that go on all weekend, with the children scampering around in the backyard until the small hours. One of these days, Kev says, he will have words with Mr Brannigan. Somehow he never does. Still, they like going to the Romany Rye on the far side of the square, or the Volunteer half a mile away on Earlham Road, which has the additional advantage of running Friday-night sweepstakes. At one of these Kev wins £40 of prime butcher’s meat and they spend the next fortnight gorging on lamb steaks, back bacon and some weird, gamey stuff which Kev says is venison. It is about this time that Kev comes home from work with that serious expression she remembers from the days when he used to sit arguing with his parents and says there is this place he has heard about in Fairfax Road and would she like to take a look? It is private rental, Kev says, but cheap and there is a nice garden and a primary school not far away, which will come in handy when the baby – Chrissie is three months pregnant – arrives. Fairfax Road is on the other side of the estate towards Eaton Park and Northfields, but Chrissie knows people there and doesn’t mind. On the evening they walk 20across to inspect the premises, the Brannigans are having one of their parties and somebody has tipped a bin over in the street. Good riddance to bad rubbish, Kev says.

Chrissie adores the flat, which is on the ground floor and takes the light. There are two bedrooms and she earmarks the second as a nursery, stencils outlines of fish on the walls and makes a mobile out of old coat-hangers and soft toys to dangle over the cot. The baby is born in July – it is 1986 now, and Norwich are back in the First Division – and Kev’s mum and dad come round to pay their respects. Kev and his parents have never got on, not ever, Kev says, but a baby is a big thing and differences have to be put aside. Long years later Chrissie will come upon a photo, taken by a neighbour, of the four of them sitting in the garden on under-sized chairs brought out from the tiny kitchenette staring at the baby – Emma-Jane she is called – as she lies on a blanket, Kev’s parents placid and benign. Already Kev has that restless, intent look clouding his features. Norwich is a small place, he says: it wears you down. But Chrissie disagrees. To her Norwich is a big, teeming city. There are parts of it – Spixworth, Sprowston, Heartsease – where she has never been. What lies beyond is unimaginably remote. This attitude, she know, is quite common. Her Aunty Steph, who lives in Shotesham, eight miles away, has only left Norfolk three times in her life.

The Fairfax Road flat lasts two years. On bright summer forenoons Chrissie takes Emma-Jane out to Eaton Park to look at the giant carp basking in their artificial lake or have tea in the bandstand café. There is a story that someone once put a pike in the carp pond which caused such havoc that it had to be retrieved by a professional 21