Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Some of the characters in Stewkey Blues have lived in Norfolk all their lives. Others are short-term residents or passage migrants. Whether young or old, self-confident or ground-down, local or blow-in, all of them are reaching uneasy compromises with the world they inhabit and the landscape in which that life takes place.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

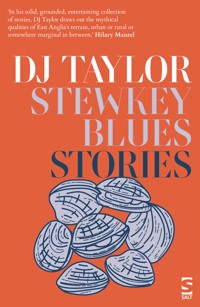

STEWKEY BLUES

STORIES

D. J. TAYLOR

‘Ha’ your fa got a dicker, bor?

‘Yis, and he want a fule to ride him. Can yer come?’

Norfolk saying

In memory of Justin Barnard 1960–2021, who knew the territory

CONTENTS

STEWKEY BLUES

STEWKEY BLUES

They came upon Stiffkey by accident, having tried and failed with Wells, Blakeney and Brancaster Staithe. From a car window all the North Norfolk villages looked the same. It had taken a week of barrelling back and forth along the A149 to establish that there was no pattern, and that only the fields of marram grass and the vast canopy of the sky were a constant. ‘Looks nice,’ Julia said as she reversed the Mini into a too-small space between two double-parked Land Rovers and a stricken 2CV that seemed to be held together with baler twine.

‘It’s pronounced Stewkey,’ Nick said, who had a copy of Ekwall’s English Place Names open on his lap and had volunteered similar information about Wymondham, Happisburgh and Great Hautbois.

‘I bet it isn’t really,’ Julia chided. ‘They just do it to annoy visitors.’ In the middle distance, sunlight glinted off the mullioned window panes and the honey-coloured thatch and there were sandpipers bouncing in and out of the air currents. Even in mid-August there was no one about.

‘I expect the coffee will be £3 here,’ Nick said, who had paid £8.50 for a cheese baguette in Burnham Market two hours before. The coffee was £3.50. When they came back to the car half an hour later the 2CV had disappeared, but there was a sheet of Basildon Bond notepaper tucked under the windscreen wiper on which someone had written in elegant cursive script A little courtesy to your fellow motorists would be appreciated.

Julia twisted the note into a paper aeroplane and sent it spinning off to join the sandpipers. ‘I just love this place,’ she said, delightedly.

Fortunately they were the kind of people who could afford to live in Stiffkey, in both senses of the word. Julia’s mother, Marjorie Devereux, summoned from Hertfordshire, plonked down £5,000 for the six-month rental without a murmur, pointed out that the damp course was defective and then drove off into the late-afternoon sun. Like the person who had left the note about parking, their new routines crept up on them by stealth. The CVs and the photographs of the people with whom Julia populated her poetry slams and her Arts Council-funded seminars – anxious-looking women with gypsy jewellery and pale boys with receding hair-lines – lay strewn around the sitting room. Nick took to conducting the Zoom conferences with the accountancy firms for whom he wrote marketing brochures and annual reports from the kitchen, laptop balanced on the pine table with its view of the distant sea. In the afternoons, when the gravel path to the beach became clogged with trippers and fat men in espadrilles with Mirror dinghies lashed to their car trailers, they went inland to Holt or Binham in search of second-hand bookshops and ruined priories. All this, Nick knew, smacked of ulterior motive. It was the same with the copies of the Holt Advertiser, the sea-horse pottery mugs and the sea-grass baskets with which Julia decorated the kitchen dresser, proof that in a world of tightly-demarcated boundaries and precise geographical margins, you had managed to go native. Here in North Norfolk the tourists were tolerated rather than encouraged. They lit fires up on the bird reserve and were run off by the wardens, and assumed that the baby seals left to sun themselves on Holkham beach were abandoned orphans. Nick had once seen a man in a Hawaiian shirt buy a dozen dressed lobsters at the Cley smokehouse without turning a hair.

Here in Stiffkey there were less expensive kinds of seafood. ‘Try to get some Stewkey Blues,’ Julia said, when he hazarded a trip to the fishmonger’s. ‘Granville says the locals love them.’ He had genned up on enough coastal lore to know that Stewkey Blues were cockles, but Granville was a new name. Over the next few days, Julia’s conversation thrummed with mention of him. ‘Granville says we ought to get tickets for the Sea Fever festival at Wells … Granville says they have point-to-points at Fakenham … Granville says the best time to have dinner at the Red Lion is Wednesday night.’ Like the scarlet buoys glimpsed at low-tide in Blakeney Harbour, he bobbed up when you least expected him. Forgetting to supply basic details of some phenomenon by which she was transfixed was one of Julia’s oldest habits, in the same category as the Christmas cards she had drawn up by an artist friend each year, full of the same symmetrical holly sprigs and the same lumpy snow scenes. The cockles, meanwhile, which bulged suggestively against the rim of the giant jam jar in which they were supplied, were hard to swallow.

‘They look like ogres’ testicles,’ he complained.

‘Granville says it’s because of the pigment,’ Julia said, spearing one with a fork and up-ending it onto a slice of olive bread. That night it rained for the first time in a month – a colossal storm that punched up from the Hook of Holland and went rampaging off into Lincolnshire and whose after-effects demonstrated that Marjorie had been right about the damp-course.

Like the deluge, and the Tornado jets that came in low over the skyline at dawn, Granville was something unforeseen: not, as Nick had half-expected, the mournful exquisite in the three-piece suit who left for Norwich each morning in a Jaguar; nor, as he had occasionally supposed, the Wellington-booted ancient who could be seen pinning up details of church services on the parish notice board, but a slender, grey-haired 50-year-old with a lurcher, whom Nick found on the doorstep on his way back from a walk picking samphire on the salt-marshes.

‘Poor crop this year,’ Granville said, tweaking one of the sprigs out of Nick’s basket, crunching it under his front teeth and holding the stalk disgustedly between finger and thumb. ‘Bit too woody for my taste.’ He had one of those high, authoritative voices that brooked no dissent. The lurcher, staring loyally at him, grey flanks aquiver, could have stepped out of a painting by Landseer. ‘Look here,’ Granville said suddenly, as if they had been engaged upon some long, fruitless argument that only a single decisive gesture could satisfactorily wind up. ‘I saw your wife the other day’ – the assumption that Julia was Nick’s wife seemed to define him in the same way as the gleam of fealty in the lurcher’s eye – ‘and we thought you might both like to look in for a drink tomorrow night.’

Who was ‘we’, Nick wondered. Granville and Julia? Granville and some as yet unspecified Mrs Granville? Granville and his mansion full of domestic staff? Unable to think of anything to say about the samphire, his non-marital status or the drink, he contented himself with a glance at the bruising sky. ‘Looks like rain again.’

‘I don’t think so,’ Granville said. He was already six or seven feet down the sandy drive. The lurcher plodded diligently at his heels. ‘Come at seven,’ he flung back over his shoulder.

Later, in the warmth of the still-fine evening, they sat out in the back garden where owls shrieked and swooped over the hedges and in the distance mysterious flashes of light broke over the mutinous sea. ‘Granville came round to ask us over for a drink,’ he volunteered.

‘Oh yes? He said he might.’ Julia, busy with the arrangements for a conference at the University of Nottingham, was deep in a poetry pamphlet called Shriven by the Zodiac.

‘Do you know where he lives?’

‘One of those newish houses down at the end of the green, I reckon. Do you think this is a good poem?’ She screwed up her eyes against the fading light and tried an incomprehensible stanza or two. ‘I was thinking of asking her to open the conference. Just before Arabella does her key-note.’

All the next afternoon, hard at work on a corporate finance brochure for Ernst &Young, Nick consoled himself by wondering about Granville’s house. A baronial pile, at whose portal the lurcher drowsed in lonely splendour? A paving-slabbed exercise in neo-brutalism tucked under the sand dunes? In the room below Julia talked avidly to poets on her smartphone. She had big plans for Shriven by the Zodiac and was commissioning its author to lead an improv session. Coming down to brew coffee in the expensive percolator Julia had bought at Larners in Holt, he glimpsed the jam jar full of cockles, abandoned between the bread bin and a heap of tea towels advertising the Brancaster coastal trail. ‘Naturally, I’m sympathetic,’ he heard Julia saying into the smartphone, ‘but I can’t have Jessica going on about her womb any more.’ Without quite knowing why, they found themselves dressing up for the evening call, putting on smartish shoes and, in Nick’s case, ironing a shirt. ‘This is like Cranford,’ Julia said, suddenly adrift on an unfamiliar social tide and desperate to bring the boat back to shore.

Granville’s house, reached a few minutes after seven (‘He’ll think it terribly rude if we turn up early,’ Julia worried), confirmed that its owner, for all his punctiliousness, was a dark horse. It was a small, practically tumbledown cottage with a line of slates missing from the roof and a dead badger curled up on the raggedy lawn. Inside, the atmosphere was more reassuring. On his own turf, Granville’s powerful tenor lost some of its twang. Offering drinks (‘What’s your poison?’), he might have been the Water Rat getting up a party in The Wind in the Willows. The drinks were all old-fashioned exotica – gin and vermouth, Campari and soda, angostura bitters. ‘Never touch it myself,’ Granville said when Nick asked for whisky, the implication being that no else should ever touch it either. From silver-edged photo frames balanced on the shelves of antique dressers, buck-teethed girls in one-piece bathing costumes stared sightlessly down. In the kitchen there were piles of old newspapers and cans of dog food. ‘Really this place could do with a clean-up,’ Granville conceded. It was Julia who saw the envelope addressed to ‘The Hon. Granville Banstead’ gleaming from a cushion. They were getting the measure of Granville now, Nick thought, sizing him up, pinning him down, the impoverished country gent in his rustic shack, where ancient silver winked from mouldy cupboards, and alumni magazines fell through the letter box onto a mat awash with pizza flyers. Going upstairs in search of the loo, he found himself looking for something that would undermine this stereotype – the wall of computers linked up to the Singapore futures market, the roomful of photocopiers awaiting despatch – but there was nothing to see: just an anchorite’s bedroom with bare floorboards and a cracked mirror hung slantwise over the sink. They arranged to have lunch with Granville at a pub in Blakeney the following week.

‘Isn’t he adorable?’ Julia said, in a way he had previously heard her speak of hamsters or friends’ slapdash children, as they tripped over the slippery paving stones that had been sunk into Granville’s garden, past the stinking badger.

‘That bottle of vermouth must have been ten years old.’ What did Granville do with his solitary evenings, Nick wondered. He had a vision of him brooding alcoholically over a meagre fire, or reading P. G. Wodehouse novels deep into the night.

‘Tomorrow,’ Julia said, who had admired the range of stout, sensible footwear on display by Granville’s front door, ‘I’m going to go into Holt and get myself a proper pair of boots.’

Autumn came in a rush. One moment the A149 was an unbroken conveyor belt of traffic; the next there were only farm trucks and hopper buses buzzing on to Hunstanton and Lynn. The fog, hanging over the salt marshes, could take hours to disappear. At dawn the sky bled extraordinary shades of cerise and magenta before settling down into an endless pale slate horizon, like the translucent toffee Nick had once seen on a trip to Hollywood being shaped into fake windows for stuntmen to jump through. ‘I talked to mother about extending the lease,’ Julia said one morning, the infinitesimal arching and un-arching of her fingers acknowledging a failure to discuss this in advance. Looking at her across the breakfast table – chilly now, despite the wall-heater – he registered some of the changes wrought upon her by three months on the east coast. They included a pair of lace-up leather half-boots from the Country Casuals store in Burnham Market and a cable-knit pullover from a shop in Wells that had cost all of £125. On the other hand, they were still sufficiently themselves to do imitations of Granville – the way he pronounced Edin-borrow, the mock-cockney intonation of ‘me mother’, his take on ‘Hunstanton’, which involved losing the second vowel altogether. ‘I’ll drive you to the station if you like,’ Julia said, which was her way of apologising for talking to Mrs Devereux about the lease.

The autumn was Nick’s busy time. It was then that the big professional services firms wanted copies of their annual reports and accounts – sober documents, heavy with the scent of corporate responsibility – to send to impressionable clients, when their senior partners were invited to address conferences held in Docklands amphitheatres. Twice, or sometimes three times a week he took the early train from Sheringham, changed at Norwich and spent the day in an office near Liverpool Street Station writing speeches about empowerment or polishing off case studies about companies whose treasury management systems had unaccountably failed them and whose lenders were about to foreclose. Outside the rain fell over Lothbury and Threadneedle Street and the familiar landmarks, looming out of the mist, looked odd and out of kilter. Who exactly was being empowered, he asked Mr Abrahams, the agency boss, and Mr Abrahams, who had laboured cynically in the Square Mile for thirty years, said ‘Why, corporate communications specialists like ourselves, Nick.’ Come the spring PricewaterhouseCoopers would probably want someone full-time, Mr Abrahams said, which was something Nick might like to think about.

But there were other things to think about back in London. One of them was the sub-let flat in Clapham with its ailing boiler and the language student tenants who had a habit of vanishing into the South Circular ether with their bills unpaid. Another was Julia, whose enthusiasm for her poets and performance artists dwindled with the November daylight. Coming back from Sheringham after one of his days out, as the gale blew in over the coast road and the taxi left a criss-cross of shattered tree-branches in its wake, he found her in the kitchen feasting off local produce: trout terrine on toast; smokehouse kippers; all the mysterious bounty of shore and stream. ‘I thought you said you didn’t like them,’ he protested, eyeing the half-empty jar of cockles.

‘It’s an acquired taste,’ Julia said, in the same decisive tone she had used that morning about the Clapham rent arrears. ‘Granville’s asked us to Fakenham Races this Sunday.’

There were plenty of acquired tastes here in North Norfolk, he thought, washing up in the empty kitchen as the wind swooped in under the door and the light bulbs danced in their shades: the espadrilled fat men with their Mirror dinghies; the head-scarved old gentlewomen on the beach who neglected to clear up after their dogs; a whole heap of complicated protocols just daring you to infringe them. The race course at Fakenham, a dozen miles away, turned up a subtle new demographic: deedy ancients putting each-way bets on the favourite; well-bred children in glistening cagoules; old ladies in Barbour jackets with hard, angular faces and tips acquired from confidential trainers. Granville, entertaining several of these people with the contents of a picnic hamper wedged into the rear-end of his mud-spattered jeep, was in his element: like Herne the Hunter, Nick thought, gliding through the forest surround and gathering up the fauna in his wake. ‘Colder here than in Scotland,’ he said. ‘I was there the other week.’

‘In Edin-borrow?’ Nick asked, not able to stop himself, and felt, rather than saw, Granville’s glint of disapproval. There was a particular horse, a pale grey mare, commended by Granville for the correctness of its gait, which sailed effortlessly over the jumps, while the animal Nick had backed came in seventh.

The trips to London were levelling off now. The senior partners of the accountancy firms had said what they wanted to say; empowerment was rife. Still, though, Mr Abrahams said, PricewaterhouseCoopers wanted him five days a week and were ‘prepared to pay handsomely for the privilege.’ Mr Abrahams liked these clichés. They reminded him of far-off days hobnobbing with the Cork Gully partners in their panelled luncheon rooms and writing press releases about the Big Bang. Knowing what Julia would say, he turned the offer down and, just to compound this sense of duty done, went off to Clapham on the tube, bled two of the radiators and helped one of the language students fill in her visa renewal form. Coming back to Stiffkey, an hour ahead of schedule, the warning text once again forestalled by the dodgy coastland signal, he found the house in darkness. A little vagrant music played softly in one of the upstairs rooms. Intrigued, he opened the front door and flicked on the light, but there was nothing to confound him: just a letter in Marjorie Devereux’s crisp, italic hand together with more pizza flyers not yet retrieved from the mat, a mouse streaking off into the wainscot and the crazy shadows flung by coats and umbrellas.

Granville, hastening downstairs with white fingers doing up the buttons of his leather waistcoat, haphazard grey hair going in all directions, looked not exactly flummoxed but somehow cast adrift. ‘Oh there you are,’ he said from the third stair up, as if their meeting was the climax of some long and wearying search and now Nick could be returned to captivity. Nick had a terrible feeling that Granville was going to make one of his pronouncements about the weather, summon up some tropical typhoon that would sweep in through the open door and blow him off his feet in an instant. From above his head came the sound of anguished, pitter-pattering footsteps. ‘Well, this is all very embarrassing,’ Granville said, who did not seem particularly embarrassed. He had finished re-buttoning the waistcoat buttons now and was running his fingers over them as if they were the keys of some obscure musical instrument that might accompany him in song. Six feet away, Nick could still hear the mouse burrowing into the wainscoting as if its life depended on it. Following its trail, he moved off into the kitchen, where the remains of supper for two – plates, cutlery, fragments of bread and butter – still lay on the breakfast table. ‘I should put that down,’ Granville advised, seeing the cockle jar in his hand. Nick stared back at him. He could think of no insult worth administering, no physical gesture worth the effort. The jar spun in his fingers. For some reason he pulled off the lid, picked out one of the grey-blue globules that floated within and threw it hard at Granville’s head. ‘Fuck off, will you?’ Granville cried. It was the most agitated Nick had ever seen him.

‘No, you fuck off,’ Nick said. The second cockle hit Granville square between the eyes.

‘Nick, you’d better stop,’ said Julia, appearing in the doorway in her dressing gown, knuckles up to her chin. Nick ignored her. All too soon his ammunition would be exhausted, but for the moment he was unexpectedly content. Granville skipped off back towards the staircase and he threw a third cockle and then a fourth, gripped by what might have been envy, or contempt, or some quite different emotion, as fathomless as the white waves that broke on the Stiffkey shore, half a mile beyond his outstretched arm.

CV

Danny Inghamis born in 1958 in Lound Road on the Earlham estate. The house is small for the five of them – two sisters follow in quick succession – but they get along. Danny’s dad works on the buses, driving the 85 along the long, threading highway of the Avenues to the old golf course on the city’s edge where they are building the new university. His mother is a quiet, dark-haired woman who sits in the front room watching soaps on the black and white TV. The highlight of her day is the afternoon trip to Bunnett Square, a quarter of a mile away, to buy a copy of the local paper, the Eastern Evening News, and stock up at Davies’s, the grocer on the corner.

Danny gets his first job aged 13, delivering newspapers for Sidney Lane. The sign in white letters on the blue shopfront says ‘S. P. Lane.’ Everyone knows that the ‘P’ stands for ‘Peacock.’ Sidney Lane is a small, bald man who lives in a flat over the premises and goes to Madeira for his holidays. The rounds stretch all over south-west Norwich, from the Earlham estate to the big houses on Christchurch Road. There is a fleet of bikes with outsize metal panniers kept in the yard for the delivery boys, but Danny likes to walk the route with the bag slung crossways over his shoulder. The people on the council estates take the Mirror and the Sun, whereas the people in the big houses on Christchurch prefer the Telegraph and The Times. Sidney Lane says he is a smart lad – people still say things like that then - and worth the £2 a week. Danny spends most of the money on records – Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars; Slade Alive – or presents for his sisters. The girls are shy and in awe of him, but they like the bags of candy bananas, the mini jars of sugared almonds and the faint cyanide scent that rises from their lids.

Delivering newspapers is harder than it looks. Some weeks Danny is spare boy, filling in for other lads who haven’t shown. On unfamiliar routes the houses can be hard to find. Plus the round book changes when people go on holiday or leave the area. But Danny has a good memory and rarely makes a mistake. Pretty soon he has an afternoon round, too, out along the roads near Eaton Park and Northfields and is earning £3.50 a week. In one of these houses in Fairfax Road a boy Danny knows called Graham Cattermole, arguing with his mother, pushes her against the fridge so that she falls over, hits her head and dies. Meanwhile, decimal currency has come in and the big old copper pennies with Queen Victoria’s head on them are giving way to tiny 1p pieces. Danny’s dad, who has an eye for these things, keeps a couple of hundred in a plastic bag in the loft on the grounds that one day they will be worth good money to collectors.

Danny is in the fourth year at secondary school now, tall like his dad, with a chipped front tooth that he has never had fixed from when someone threw a satchel at him. His parents wanted him to go to C. N. S. or the Hewett, but somehow he ended up at the Bowthorpe in West Earlham, the worst school in Norwich, where most of the kids leave at 16. Mrs Marsden, the careers teacher, recommends a job at one of the boot and shoe factories, but Danny has a better idea. Mr Lane says he can help out at the shop, sort out the rounds in the morning and bag up the returns for collection next day by the delivery van. The pay will be £20 a week. Danny celebrates by tearing up his school blazer and drinking half a bottle of vodka from the Bunnett Square off-licence. It is the summer of 1973 and the newspapers’ front pages have pictures of Mr Heath at the helm of his yacht, Morning Cloud. His mother’s favourite TV programmes are Coronation Street and Steptoe and Son. His dad prefers the Benny Hill Show, which has big-breasted girls in their underwear scampering back and forth across the screen.

Somehow, working together in the shop, Danny and Mr Lane can’t get along. They argue about getting the delivery bikes repaired, and whether to extend the rounds into West Earlham. Plus the work is exhausting – Danny has to be at the shop by 6 to sort the morning rounds and isn’t supposed to leave until the afternoon boys are finished. In his mid-morning break he goes out into Bunnett Square and stares into the shop windows. There are several other premises on this side of the square: a chemist’s; an old man who sells bicycle spares and ironmongery; Oelrich’s the baker’s; a betting shop and the Romany Rye pub. One November morning when Danny has just turned 17, Mr Lane finds him with his hand in the till, which is too big to be ignored. Danny, who knows that Mr Lane has been looking for an excuse to get rid of him, wishes he had left the £5 note untouched, but it is too late. Still, Mr Lane writes him a reference that says he is a reliable young man who with the right kind of encouragement can make a valuable contribution to any organisation of which he is a part. On the strength of this, Danny gets a job at the Rowntree Mackintosh factory in Chapelfield. The smell of cooking chocolate is one of the two smells that always hang over Norwich; the other is the reek of sulphur from the May & Baker factory on the ringroad. Danny is put on the production line, in hair net and white coat, where his brief is to weed out duds, and is told he can eat anything he likes. The theory is that anyone who works at the factory will be sick of chocolate after a week, but Danny never tires of peppermint creams and Black Magic. In three months he has put on a stone. That summer there is a drought and the grass in Eaton Park turns brown for lack of moisture. His dad says he is worried about Danny’s mum, who doesn’t like to leave the house and some days barely moves from her chair in the front room. Danny’s sister Alison, who goes to C. N. S., passes seven ‘O’ Levels, and says that she wants to stay on in the sixth form to study English, French and Mathematics.

Meanwhile, Lound Road is changing. The old people who have lived there since the estate was built are mostly gone now and the new families don’t stay so long. There are more cars parked up on the narrow kerbs and it is less safe for children to play. When they first moved in all the neighbours were in and out of each other’s houses, Danny’s mum says. Danny thinks this is just the way older people talk. Chrissie, who lives in Thorpe in the north of the city, says her parents are just the same. Chrissie is a year younger than him and works at the Norwich Union Insurance Society. She is a pale, intense girl with bitten-down fingers, freckled skin and bright red hair twisted up in a slide. Chrissie likes Northern Soul music by Johnnie Guitar Watson and Wigan’s Ovation and teaches him some of the dance moves. There is a pub five miles away in Sprowston that has Northern Soul nights and they go over there on the bus, walking home in the small hours through the dark streets. Some of the boys who come to dance can leap five feet high in the air. Once, jostling in the queue to get in, an angry kid waves a knuckleduster at them, but Danny faces him down.

Somehow Danny can’t get on at the factory. The sweet, heavy scent of the chocolate boiling up in the vats makes him feel sick, and the job in the packing department, to which he graduates after a year, is deadly dull. Plus they are strict about time-keeping. Chrissie, who spends her working hours altering addresses in a giant box of index cards, says that Danny doesn’t know when he is well off. In Bunnett Square the old man who sells ironmongery and bicycle spares closes down and is replaced by a boutique called Melanie’s Modern Modes. Davies’s the grocer starts selling oven-ready pizza and Ski yoghurt. Danny’s dad is put on a different route, which takes him to Bungay, Southwold and the Suffolk market towns. His mum spends nearly all the day watching the TV now: the lunchtime news; children’s shows; discussion programmes; anything. She has favourites among the presenters and complains when Angela Rippon isn’t on. Danny’s friend Keith, whose mother died when he was five, says it could be a whole lot worse. Danny and Keith know each other from way back at primary school. They go fishing at the UEA broad or the big trout lakes, staying out all night in tents pitched at the water’s edge. When Keith says there is a vacancy at the butcher’s where he works, Danny jumps at it. The butcher, Mr Daniels, is an old man with white hair and a sense of humour who calls his staff ‘gents’. There are two other boys besides Danny and Keith. The job pays badly but you can buy meat at discount. Plus there are always people to talk to. Sometimes, when trade is slack, Mr Daniels tells them stories about the Arctic convoys he served on in the war, and being trapped below decks in a ship that had been holed beneath the waterline. Danny discovers that he quite likes working in the butcher’s shop, heaving sides of beef into the freezer room or standing behind the counter in his blue and white pinstripe apron chopping up chicken pieces. He is smoking a cigarette outside the shop one morning in the spring of 1978 when Chrissie arrives to tell him she is pregnant.

In those days girls who get pregnant get married. It is as simple – or as complicated – as that. The wedding takes place at St Anne’s church on Colman Road on a scorching day in June. Danny’s sisters are bridesmaids, in bright yellow dresses from C&A. Alison will be going to Leeds University in the autumn to study Modern Languages. Melissa, two years younger, has a job as a dental nurse at the surgery in Earlham Road. Danny’s dad says it is nice to see people making something of themselves, which Danny takes as a reproach. He gets drunk at the reception, which is held at the parish hall behind the church, and is sick in the taxi on their way to the hotel where they are spending their wedding night. Two weeks before Chrissie gives him a £20 note and tells him he has to be able to smile in the wedding photo. He takes the money to a private practice in one of the big houses on Newmarket Road and has the dentist fix his chipped tooth with a lump of amalgam. For a honeymoon they stay a week in a boarding house in Cromer that smells of fried bacon, and spend the time taking bus rides up and down the coast to Wells, Hunstanton and Burnham Overy Staithe, where Danny casts envious eyes on the anglers fishing for cod, skate and sea bass.

There is a plan to live with Chrissie’s parents, but Danny and Chrissie’s dad don’t get on. Plus it is too far for his work. Instead they rent a flat in Cadge Road in West Earlham. Cadge Road is supposed to be the worst street in Norwich, but Danny doesn’t mind. It is handy for the butcher’s shop and the Five Ways pub where he and Keith talk about fishing. It is the winter where the Government are fighting the unions and the electricity goes off at unexpected times. The baby is born on Christmas Day in the Norfolk & Norwich Hospital, where there are sprigs of holly wound round the strip-lights and banks of Christmas cards on the bedside tables, and is christened Olivia Katherine Ingham, after the actress in Grease, which Chrissie has seen half a dozen times, and Danny’s mum. Seeing her lying in the travelling cot that accompanies her back to Cadge Road, Danny is unexpectedly moved. He takes the baby out of the cot several times an hour to see if she is OK and gets up in the night to check on her. Keith, who has two of his own, says this is what kids do to you. Once again, things are changing. The university down the road in Colney is expanding, and the streets are full of students cycling in from their digs. Alison sends postcards from Leeds, says she enjoying herself and has a boyfriend called Hanif. Danny discovers that Chrissie, too, has plans. The spare room in the flat is converted into a nursery. Danny papers the walls and paints the ceiling, but it is Chrissie who suspends the mobile toys over the cot and installs the brightly-coloured fixtures. Seeing her at work, Danny wonders what has got into her and what the outcome will be. Meanwhile, Danny’s dad says that his mum hasn’t left the house in Lound Road for three months.

When Olivia is four months old, Chrissie says she has been thinking and that she and her friend Elaine are going into business together cleaning houses. Olivia can spend the day with her nan and grandad in Thorpe. Chrissie and Elaine call themselves THE CLEAN TEAM and work for women in the big houses on Newmarket Road, hoovering floors and polishing sideboards. The business is a success. With the first half-year’s profit they buy a van with a picture of a woman banging out a carpet on the side. Just now Danny is planning to leave the butcher’s, where trade is bad, the number of assistants has dwindled to three and Mr Daniels is thinking of retiring. Once, around this time, he reads a newspaper that says: PROSPECTIVE EMPLOYEES – WHAT ARE YOUR SKILLS? One thing Danny can do is drive. Even his dad, who taught him on one of the abandoned air bases out on the Norfolk flat, says he is a natural. He talks it over with Chrissie, and they decide that he will apply for a job at one of the mini-cab firms in the Prince of Wales Road. Chrissie has taken out her slide and has a new hair-style, bobbed and fluffed up at the front, like Lady Diana Spencer, who everyone says is going to marry Prince Charles.