45,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

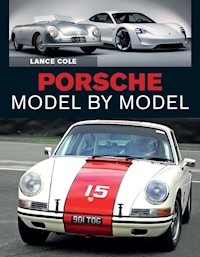

Taking a fresh approach, this book delivers an up-to-date review by investigating the essential characteristics, design and driving experience that defines the Porsche legend and its cars. From icons like the 356 and 911, through to the transaxle Porsches and recent models of Boxster, Cayman, Panamera, Macan, Tycan and more, Porsche Model by Model offers a detailed yet engaging commentary upon the marque. With over 275 archive and specially commissioned photographs, this book presents the full marque history from Ferdinand Porsche's defining Bohemian effect to the brand and design language today. It covers the 356 to the Taycan in concise yet detailed discussions; explores historical and technical details including specification tables and includes driving descriptions and owners' views.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

PORSCHE

MODEL BY MODEL

Eagle-eyed readers will know this ‘RSR’ is a delight and a modified car but is very interesting and very real.

PORSCHE

MODEL BY MODEL

LANCE COLE

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Lance Cole 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 736 1

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

CONTENTS

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Porsche – Timeline

Introduction: Old Wien and New Borders

CHAPTER 1 PORSCHE PRECURSOR

CHAPTER 2 356: DEFINING MOMENT

CHAPTER 3 901–911: CLASSIC ICON

CHAPTER 4 996–997–991–992: AFTERWARDS AND BEFORE

CHAPTER 5 914 VIERZEHNER – THE MISUNDERSTOOD PORSCHE?

CHAPTER 6 924–944–968–928: TRANSAXLE KLASSE

CHAPTER 7 BOXSTER & CAYMAN: ACCESSIBLE PORSCHE

CHAPTER 8 CARRERA GT TO 918

CHAPTER 9 CAYENNE & MACAN TO PANAMERA: A DIFFERENT ROAD

CHAPTER 10 TAYCAN

References

Bibliography

Appendix: Porsche racing special cars of the classic era

Index

DEDICATION

To unseen friends amid voices from beyond the gates of remembrance

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Porsche Club GB and its members have made numerous contributions to my knowledge base, and thanks must go to Chris Sweeting at Porsche Club GB headquarters. Porsche GB and Porsche AG have provided research and factual reference assistance and some photographs to complement my own. Porsche people at Official Porsche Centre Reading and OPC Tewksbury and the OPC Porsche Classic Centre Swindon have also been very kind (special thanks to John Sharp). I would like to thank former friends at Autocar (the late Michael Scarlett, and the late Jeff Daniels) and Classic Cars, and at the Royal College of Art Vehicle Design Unit. Josh Sadler has imparted some wisdom and the folks at Autofarm were very kind. Steve Bull Porsche at Devizes must also be thanked for kindness and time given. Thanks to 924-racer Justin Mather (a Prescott top class performer) for advice. Tim Read – classic 911 owner and old friend gave his time. The Amalgam Collection kindly assisted with 911 model photography. Donald Peach, Porsche 928/944 owner and Prescott man gave time and of his 928 and knowledge. I would also like to acknowledge people no longer with us – Jeremy Snook once of Porsche GB, Dawson Sellar the designer, Richard Soderberg, and departed Bavarian friends. I have consulted the vast bibliography of Porsche and its archive, and must acknowledge the works of Ludvigsen, Frère, Clausager, von Frankenburg, for their reference points. Ludvigsen offers a view that I find rational and well referenced – as do many others. His tome, Porsche Excellence was Expected, defines the Porsche tale in its own excellent way. Other books consulted as reference points are listed in the Bibliography. Crowood have published several Porsche books and these provide an excellent viewpoint. Former colleagues in the motoring press have also given me a steer. A salute to Porsche Post, 911 and Porsche World magazine, and Total 911 magazine, of which I read very issue. Thanks to several Porsche owners for the drives. Last, but never least, to my wife Anna for her love and the fact that she likes 911s – old ones.

Photographic notes:

Of the 250 or so photographs in this book, many of them (over 150) including the main cover photograph were taken by the author on Nikon DSLR cameras and lenses. Several vintage, classic and recent Porsche and Porsche model range photographs are from the Porsche media sets or Porsche archive and used with permission from Porsche for editorial. The excellence of the relevant Porsche photographers works is hereby acknowledged. Any error in credit or origination is entirely accidental.

Please note: the author Lance F. Cole, has no connection with ‘Lance Cole Photography’ or such named website, trading, actions or operator.

PORSCHE – TIMELINE

1875 Ferdinand Porsche born

1890s F. Porsche begins car design studies and electric power research

1902 F. Porsche delivers first car to a British customer

1899–1907 F. Porsche designs electric motors in working electromobile cars for Lohner-Porsche and Daimler.

1910 F. Porsche designs an aerodynamic car, and goes racing

1912 F. Porsche designs first air-cooled engine

1916 F. Porsche is Director of Austro-Daimler

1920s F. Porsche works for major auto-makers and designs his first small car and a racing variant

1930 Establishes own Porsche design company bureau

1930s Grand Prix cars designed, Auto-Union, and VW ‘Beetle’ designed

1938 Porsche Design office moves to Zuffenhausen. Speed record-cars designed

1939–1945 War time works

1946 Porsche creates the Cisitalia racing car and Porsche projects including tractors

1947 Life at Gmünd

1949 First Roadster – to become the 356 project

1950 First 356 Coupé and 1950s range develops: 550 Spyder and RS cars

1951 Ferdinand Porsche dies and son Ferry Porsche takes over

1953 First of the new Zuffenhausen factory buildings opens

1963 911 announced, on sale 1964, becomes global icon

1972 911 Carrera RS legend evolves. Works 917 wins the Can Am race

1970s Racing success for Porsche: Multiple Daytona wins and Le Mans winners with 917

1980s New transaxle cars establish lineage: 924 Turbo and 928S evolve

1990s 911 developments to 993-series

1996 New 911/996 design and Boxster announced

1998 Ferry Porsche dies

2002 Porsche makes a sports-SUV Cayenne: Macan to follow

2005 Carrera GT project. Cayman launched

2012 F.A. ‘Butzi’ Porsche dies

2013 918 Spyder

2015 Six Porsche Centre factory plants and the Museum exist

919 wins Le Mans with three victories in a total of 17 wins. Hybrid technology evolves

2015 911 991-series marks new era of 911’s design: Cayman GT4 launched

2020 Taycan electric range established and EV-hybrid 911 to come

2021 New 911 GTR3 announced as naturally aspirated petrol-powered icon

INTRODUCTION

Classic 911s in action at the Goodwood circuit during the Aldington Cup race. Note the rubber bonnet straps and front valance with air intakes.AUTHOR

INTRODUCTION :

OLD WIEN AND NEW BORDERS

Littered across this landscape were some of the greatest and most intelligent names of the first epoch of the motor car. Ferdinand Porsche rose to become the leader of their pack.

THERE HAVE BEEN MANY Porsche books and there will be many more. Sometimes the groan goes up, ‘Oh no, not another Porsche book.’ So while some regurgitation of history is unavoidable, the interpretation of it and its cause and effect is where we can further our understanding – supported by a framing of the vital ingredients of Porsche and that elemental DNA of what is a Porsche.

I am always concerned to be invited to read yet another marque or model history when the book in question simply re-presents known-knowns. So this book attempts to be not only up to date, but also to be different in its forensic approach and design discussions amid a Porsche driver’s enthusiasm. Being English but of northern European mainland heritage – with Swedish, Dutch and Bohemian familial and bloodline connections – I have tried to bring an appreciation of the wider influences to this Porsche story without straying from the path of the narrative’s intent – the cars.

As an edited history of each model, it is inevitable that a more concise version of each respective car’s story is presented here, in comparison with that found in complete books about specific models. Crowood has produced several such single-model Porsche books and those seeking such specifics are invited to consider these excellent Porsche texts.

The Cayman is small and nimble – like a Porsche should be. This one is haring through the Esses halfway up Prescott Hill Climb. The rear wing adds downforce, to put it mildly! Darren Slater is at the wheel during the 2018 Petro-Canada Lubricants Porsche Club National Hill Climb Championship.AUTHOR

The British have long had connections to Porsche. In fact, Ferdinand built and sold a car to a British customer in 1902, and he came to Britain in the 1930s to talk with Herbert Austin. Britain remains a major Porsche outpost, as does the United States of America.

Porsche’s latest is the Taycan and it might just change people’s perceptions about all-electric vehicles. Critics of EVs need to drive a Taycan, but that aside, its engineering and styling are supreme acts of Porsche style and design genius. It also somehow reeks of its German–Austrian–Bohemian lineage: the Taycan looks like a Porsche and drives like one too.

Indeed, if you think that Porsche as a company or brand is (a) German, and (b) ‘posh’ or upmarket, you would be both right and wrong. For the truth is that Porsche began as neither of these things. And in an age when the word ‘uber’ is fashionably used in English slang to describe anything needing the emphasis of being in some way special, it is bizarre to think of people describing an ‘uber Porsche’. There is no such thing, for all Porsche cars are special and, as über in German refers to ‘about’, ‘across’ or ‘over’, the idea of uber-this or uber-that seems strange. German Porsche owners find it very odd to hear a Porsche described as uberextreme or uber-something. And then they get confused about the taxi company of the same name and wonder if Uber is using Porsches!

A 911 with Gulf livery and extended bodywork driven by Chris Stone storms up Prescott in a blur of pure Porsche passion.AUTHOR

So current perception has it that the global star that is the Porsche brand is, to coin a phrase, ‘uber-German’; technically, this is accurate because Porsche AG is based at Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen in Germany. But despite the aura of German engineering excellence, so heavily emphasized, Porsche the company, its founder Ferdinand Porsche and nearly all his main engineers and designers were not German in the modern context of that geo-political definition. Austria and a Bohemian enclave is where Porsche originated and still has links and affiliations. Indeed, conscious of Austria’s engineering past and lack of a car maker (Steyr engineering notwithstanding), in the 1970s the Austrian government paid Porsche to design a new Austrian car that could have become an Austro-Porsche brand. It did not reach fruition.

Of all the Austro-Bohemian car designers and manufacturers – and there were many – Porsche remains the leader across decades, in fact across two centuries. Today, the Porsche family remain Austrian, as well as being Austro-German in business. Neither was the Porsche family upper class, posh or rich, which are all frameworks frequently associated with Porsche’s expensive or ‘elite’ motor cars; posh, and rich being two entirely different constructs and behaviours that rarely combine.

The truth is that Porsche AG had Austrians on its Operating Board until as late as 1981 when its first German-born leader was announced in the German-American Peter W. Schutz. Like so many Porsche men, he too was an engineer. The separate Porsche SE Supervisory Board (German companies have a dual board structure), remains Austrian-run.

Ferdinand Anton Ernst ‘Ferry’ Porsche – son of Ferdinand the originator – also had to work with the Piëch side of the family: representatives of both branches of the family dominated Porsche across the decades, until the Board intervened in 1971 and Ernst Fuhrmann returned to lead Porsche. After Furhmann came Peter Schutz, and others including Wendelin Wiedeking.

Ferdinand Piëch, an engineer and Ferdinand Porsche’s grandson, had started his career at Porsche and he left, only to return to Porsche power many years later when the VW group purchased Porsche. Piëch has recently died, and he left a huge mark on Porsche, VW and the auto-industry and – it might be alleged by some – possible effects upon those less powerful than himself.

Today’s Porsche brand and Porsche family headed by Ferdinand’s grandson Wolfgang are of course upmarket and exquisitely mannered. Wolfgang (who trained as a metal worker before entering the business world) is a grounded and humble man with a disdain for arrogance, and seems the ideal custodian of the vital Porsche ethos of driver enthusiasm, which must always triumph over ego, self-entitlement and fashion. Under him, we can be hopeful that Porsche will avoid frippery and bling, although currently Porsche seems to have a minor obsession with putting gold-painted wheels on its photographic and press cars, which seems a bit much to purists, unless they can recall the 1970s.

Under Porsche’s current curator, driving and cars will be to the fore – Fahren in seiner schönster form (‘driving in its most beautiful form’).

Porsche remains the leading sports car brand in the world, but it is much deeper than that; it is a design language, a unique function, a hugely respected crucible of engineering. What I call the ‘Porsche process’ is the critical ingredient that makes these vehicles something other than just cars.

As for ‘diesel gate’ and the VW emissions scandal, with Porsche structurally related and its own subsequent decision to cease diesel production, we have to be careful what we say, but suffice it to state that the usual corporate tactic of trying to find someone to blame may become unedifying, especially in the absence of a key witness who happened to be at the wheel.

Ferdinand Porsche (son of a village tin smith, descendent of a stocking maker) and his company became wealthy and identified with Germany, but the vital truth is that Ferdinand was an Austro-Bohemian who grew up as the old Bohemian geopolitical framework of the Austro-Hungarian empire faded, at a time when the map of Europe splintered into the politics of World War I. By 1919, Bohemia and the Habsburg Empire of the Schönbrunn elite were gone, replaced by a blend of borders that included Czechoslovakia and then the German Sudetenland, amid the stunning scenery of the Austrian–German–Italian border lands of what was once the epicentre of advanced car design that lay in an arc from Vienna to Berlin via Prague and Turin.

Littered across this landscape were some of the greatest and most intelligent names of the first epoch of the motor car. Ferdinand Porsche rose to become the leader of their pack. Porsche worked in Bohemia, Austria and the new Czechoslovakian arena, and went back and forth to Stuttgart in Germany during the 1920s, but his DNA, his cultural philosophy, his being, his ties were not German. And if it had not been for World War II, Porsche might not have ended up as a German resident nor moved to Gmünd in Austria – he may well have stayed nearer to Vienna or Prague.

Ferdinand spoke Austrian-German with a Bohemian singsong lilt and was – according to reliable sources – a typically temperamental Viennese. He could, say some, be a difficult character. Yet he was correct and proper and not in any sense of current ‘Bohemian lifestyle’ interpretation, but he was charismatic and of old Bohemia, and very fond of the land and of the family. Initially, he certainly surrounded himself with relaxed Austrians, not Germans. He got on well with engineers from the Austrian–Italian Tirol region, too.

Professor Porsche, as we should call him, must have had a touch of OCD – in the good way that great designers and inventors must have to succeed. He was a workaholic whose ethos was to think laterally, embrace risky new thoughts and ideas, and to continuously improve even his own brilliant ideas; continuous improvement became a Porsche hallmark.

Such facts seem to have become a touch obscured by the mighty Porsche AG Zuffenhausen, Stuttgart branding machine, but within the company there are those who know just how important these truths are to the Porsche story and even to the character of the new cars it turns out today: Ferdinand’s personality traits and culture still manifest, as do those of his son Dr Ferry Porsche and his grandson Butzi, who died in 2012.

Perhaps, as Porsche’s all-electric Taycan debuts, and as hybrid and electric cars now come to the fore, we should recall that Ferdinand Porsche designed and built electric cars over a hundred years ago even while the rest of the nascent car manufacturers were pursuing the petrol combustion engine. Faced with such, Ferdinand adapted his all-electric design ideas to combined electro-petrol hybrid engine design with axle hub drive mechanisms. How prescient was that? Ferdinand believed in electric cars and was fervent in that belief. It has only taken us 120 years to agree with his future vision!

In that time, Porsche went on to produce some of the best combustion-engined cars in the world, yet all the time looking towards the future of engineering and design. It is against this backdrop of a distinct Porsche design research psychology and effect, that I wrote this book.

A 964 hastens away from the camera in a blur of Porsche design sculpture.AUTHOR

The late Dawson Sellar – proud Scot and the first British person to design for Porsche – has also been a guiding hand from the past. He was a Porsche and BMW designer, and the Royal College of Art auto design unit’s co-founder with Peter Stevens – car designer and McLaren F1 shaper.

Sellar, of whom I wrote an obituary (which was published in the Porsche Post of the Porsche Club GB), proved you did not have to be from Swabia or Carinthia to ‘get’ what Porsche was about. In his youth he drove Betty Haig’s old, blue 356 Speedster registration number XYE 84. He recently owned 928s and a new Macan. I met Sellar a few times and he was a fantastic man and brilliant designer: Sellar married a famous Finnish designer and their daughter continues the design focus.

Another charismatic Porsche figure was the Latvian-American design leader Anatole ‘Tony’ Lapine – another northern European emigré who gravitated to Stuttgart. Wolfgang Möbius was a Lapine team member and greatly influenced the timeless form of the 928. Richard Soderberg played a major role in design, as did the Dutchman Haarm Lagaay (Laagij) who also carved out Porsche in its more modern era and whose contribution should not be underestimated. Other designers from as far afield as Hong Kong (Pinky Lai), Turkey (Hakan Saracoglu), the USA (Grant Larsson) and Brits like Steve Murkett and A.R. ‘Tony’ Hatter (senior design and style leader at the Porsche studio) can be found in the modern Porsche story. As for Michael Mauer, once heading Saab design and now heading Porsche design, all I can say is, lucky man!

I regularly devour the world’s best-selling Porsche monthly magazine, 911 & Porsche World, and it really is the best thing since Fuchs wheels. I also read the very good Total 911 magazine. Both offer differing but wonderful perspectives upon the world of Porsche enthusiasm. Other very good Porsche publications are also available, but few marques are complemented by something as superb as 911 & Porsche World, A recent highlight has been the discovery of the wonderful Duck and Whale magazine. I am just a dedicated reader – and the same goes for the different Total 911 magazine. The Porsche Club GB publish Porsche Post and it is a journal of cars and people par excellence. In America, a Porsche magazine is named Excellence. Lee Dean’s amazing Duck and Whale magazine is as must-see as the Porsches it portrays.

My family have worked for General Motors in America and Saab in Sweden, and for Skoda and Toyota, and a past relative was a key figure in the story of BMW: cars (and aviation) and design are in my own DNA. We are a motor-industry family. I have always loved the small, early 1947 Saab prototype and its consequent 92-96 range, the 1930s Citroëns, and the smaller and earlier Lancias and Fiats, and the cars of Ledwinka, Tatra and NSU all appeal to me. But Porsche and its 356, and all that stemmed from there do, to me, occupy similar engineering design ground amid a very close ethos of the small, aerodynamic, efficient, mid-European car that was either rear-engined or front-driven, in a body of clever design; such ethos is where Ferdinand Porsche was rooted.

The new face of Porsche – the Taycan. This car very cleverly amalgamates a series of Porsche design motifs into a new design language that is innovative and not a retro-pastiche: a near-impossible task, but one superbly achievedPORSCHE

Wolfgang Möbius penned the essential design elements of the 928 that were unique and beyond fashion, which is why it still looks so stunning. Even from above, every line works on this 928S4 (a rare manual owned by Donald Peach) with the later rear wing.AUTHOR

I had the privilege of listening to Paul Frère and also Jeff Daniels on Porsche. I had quite a lot to do with Porsche back in the 1980s when I was, firstly, a young trainee car stylist, and then an annoying young motoring journalist as a Lyons Scholar. This award opened up many doors and some time working at Autocar – the world’s oldest motoring publication. By luck and intuition, I was the first journalist in the door at Porsche Cars GB when the one-off Gruppe B 959 prototype arrived – because I lived up the road! Porsche’s Jeremy Snook complimented me on my being first in and laid on a treat. Since then, I have ebbed and flowed about Porsche – and recently wrote some harsh words about how bloated and short-nosed I felt the 911 had become, and did not the Cayman better carry the ethos of the nimble Porsche in a more correct manner – á la 356?

I was not alone in such sentiments. We Porsche fanatics are a tribal lot, and are of many different social and demographic types. Some are purists, some will not tolerate anything post-1975, or post-1986, some accept water-cooling, some do not. Luftgekühlt (air-cooled) remains an obsessive ethos, and why not? And yet people forget that it is the oil – as oil-flow circulating inside an air-cooled engine – that plays a major role in cooling the engine’s forged and cast metal/alloy components. So an engine subject to wafts of external airflow might be said to be internally cooled by a liquid – oil, not air and not water either. Now, there is something rarely stated.

But 911 ‘purism’ does have its place and its tribe of dedicated followers. Josh Sadler, the man for whom the 911 has been a major story and who is himself a significant part of the 911 ownership and motor sport legend, said some wise words to me on this subject: ‘Porsche purism is fine, but the point is, what are you going to be purist about?’

Sadler (without doubt the 'ducktail druid') makes a good point. He has recently sold his earlier 911 S/T factory development car (registered VRC 911S) that was one of just forty such 1969–1970 chassis; a car that he had restored using original Porsche parts. In its place is his similarly registered race/hill climb car, of 1975 provenance and much modification. It was originally a Bob Watson-modified 3.5-litre and now has a twin-plug distributor and many other ‘RSR’-effect tweaks. Sadler is also the man that rescued the purple 911 Turbo from a shed in a field in Jamaica – what a story.

Sadler promotes a rational, Porsche position of preference but not of blinkered tribalism – though he is a dedicated 911 man. As so many are (and yes, women love 911s too). Sadler took his 911 S/T car to California for the 2015 Rennsport Reunion and then toured the Pacific Coast Highway. Nice work if you can get it.

The Richard Tuthill concern, so long associated with the 911, is still preparing rally-spec 911s and former Saab rally driver Stig Blomqvist recently won the East African Classic Safari in a lovely blue Tuthill 911 – the second time a Tuthill car has triumphed on that rally, Björn Waldegård being the previous Tuthill 911 driving victor. In 2015, Tuthill-prepped 911s took over half of the top-ten places on the Classic Safari.

Talking of Africa, there must be more ‘barn find’ 911s out there, and I know where a 356 is hidden in the outback of Zimbabwe. We also know that a handful of original 356s reside in Cuba. Porsches, you see, got everywhere – even Uruguay.

The 911 gets a major share of the pages herein and it is only correct that it does, but not at the expense of 924 or 944 – or of a broader view of Porsche and the often wedge-shaped forms of its cars. Some people ignore front-engined Porsches, but I fail to understand that because it is a self-limiting psychology and Ferdinand Porsche never suffered from that! And as the first ‘true’ Porsche, the 356, used several crucial, Porsche-designed VW components, why be so snooty about the later 924 that used VW-Audi parts? I believe that just like the ‘pure’ 912, the time of the transaxle cars will come. The 914 has its followers, also.

This unusual 911 was owned by renowned Porsche expert and racer Josh Sadler. The car uses original Porsche parts in the shell of one of about forty rare factory development prototypes from late 1968. Note the extended arches, larger wheels … and utter desirability.AUTHOR

I suppose I do have left-field ‘Porsche purist’ tendencies, but they are not preserved in the aspic of dogma. The fact is that the reality of a changing world is upon us. I still reject drive-by-digital authoritarianism, but will not reject the Taycan even if is so bizarrely tagged ‘Turbo’. My next Porsche will be a renovated later 996 or an early 997. My dreams of an early 912 have been excised by fiscal facts.

One thing we can say for sure is that you, and I, certainly cannot please all Porsche fans all the time.

The respected expert Porschephile Johnny Tipler has written several, personally informed Porsche books for Crowood and I have not attempted to mimic his approach, but rather to pursue my own for this Crowood book – but guided by several hands. I hope a different ‘voice’ is acceptable to the Porsche community and to the readers of my favourite Porsche magazines. Little is definitive and this book does not attempt such a benchmark: rather than that, it is a Porsche enthusiast’s conversation in which I hope the reader will engage.

Early 911s captured in a painting by the author: sheer 911 enthusiasm.AUTHOR

The Derek Bell/Stefan Bellof Porsche 956 car for the 1983 season – a Le Mans car of course. Aerodynamic and forensically engineered, this was Porsche perfection.AUTHOR

I am sure some will take issue with something in this book – people always do and social media has encouraged attack without responsibility, or thought for the consequences of action. Polite and constructive criticism will be faced, but entirely selective and unbalanced reaction will be ignored. My answer to such is to tell complainants to write their own book.

This book is a Porsche story, describing the cars to date model-by-model. And yes, I have given the Cayenne and Macan 4×4 softroaders fewer words than other Porsches. If that disappoints you, please accept an apology but not a recanting. Good as the Cayenne and Macan undoubtedly are, they are not quite what was envisaged – worthy, but perhaps a case of the marketing defining the car, rather than the car defining the brand as in the past, the old ways of doing things. Proof of that assertion must lie in the brand-over-brains exercise that is the Cayenne Coupé. The new Porsche era has led us to brilliant hybrids and the Taycan as pure Porscheism. Porsche has stopped selling diesel-engined cars and decided to fit multiple emissions filters to its petrol-engined cars.

Porsche is about performance in all areas, not just engines. Porsche also understands the difference between power and thrust, which are two separate entities – thrust being better termed as torque in an automotive context. Porsche spent millions on its racing and rallying projects, and the things it learned in those projects have always filtered down to the road cars. This is another part of what I call the Porsche process. Stand at Le Mans or the Le Mans Classic, and see the Porsche process in action.

A more recent Porsche victory at Le Mans was in 2015 with the hybrid 919-series car driven by Nick Tandy, Nico Hülkenberg and Earl Bamber. Porsche car No. 17 was second. The drama of the car racing at night is captured in this painting by the author.AUTHOR

Two decades or so earlier, Porsche’s Gulf-Liveried 917 also stormed through the night to win Le Mans – this one is captured in close up detail by the author in a recent Porsche painting.AUTHOR

How many people know that Porsche was commissioned to design cars by manufacturers from many countries? That Studebaker paid Porsche to design it a prototype salon – the Porsche Type-542 and the TAG McLaren racing engine was of Porsche provenance? Volkswagen 4-series saloons and fastbacks of the 1960s? A Porsche design as Type 726/II in 1958? Porsche even designed a car for the Russians and assisted Volvo, too. You could even have purchased a Porsche-engined light aircraft. Porsche’s history is amazing. Butzi Porsche set up his own Porsche Design Company in the 1970s.

As we get ready to roll, please know that I have frightened myself in a 911 going sideways at high speed on an East African rally stage, I have worried myself just-about-doing 150mph on a greasy wet autobahn south of Munich in a 928, and also in a 959. I have loved pottering about in old 911s and 356s. I once travelled First Class on Lufthansa from Frankfurt and was driven from the lounge to the steps of the 747 in a dark blue Panamera as part of the front-of-aircraft ticket experience. It was indeed elitist but utterly fantastic in its sense of Porsche occasion. Talking to ex-Porsche designers over the years has also been an education.

As my wife can confirm, I am always in my room sketching new Porsche designs and Porsche is a form of mistress. And the Porsche moments keep on coming: the first-ever ‘Porsche at Prescott’ was world-class and so engaging and friendly, and as for the cars – see the photographs I have taken of Porsches herein.

As stated, I love old Saabs, Lancias, Citroëns, and even Voisins, but I always come back to the utterly essential design language and engineering process of Porsche. Personally I think the Taycan is the future when the past of petrol is over – which is not far off, but many will disagree and call the Taycan heresy. All I can say is that Porsche is facing reality – loathe it as you or I might, or might not.

I am not uncritical of Porsche and this book is no corporate tome of nothing but praise. The newer 911 generation is in my eyes, to my personally subjective taste, too short-nosed and too digital; it is a great car and yes, please, can I have a Gentian Blue one. But in terms of driving on normal roads, not motorways or ultra-smooth inter-county German tarmac, the 911-992 series is still a touch wide. I love its design, but not its size. Only the new 992 Carrera base model offers long-travel-suspension: all the others have at least 10mm less ride-height, which will be a pain – especially when allied to the massive 21-inch wheels that everyone will choose. Fine on the autobahn, freeway or motorway, but you try it on a pock-marked, patched, and knobbly A-class cross-country road in the UK, France, Australia or the USA. But marketing will triumph and GTR-something or GTS-badging will achieve the greater sales.

Porsche people: the man in the tweed flat cap in the middle is Richard Attwood – 1970 Le Mans winner for Porsche and about to race a classic 911 at Goodwood.AUTHOR

An early-series 911 ready to race at Goodwood. This car had the full cage and a non-standard steering wheel. It is in fact an ex-Vic Elford car and an SWB variant.AUTHOR

Justin Mather is well known for taking his supercharged 924/944 Special (with Augment Automotive tweaking) up Prescott Hill Climb in very quick time. Here, it was captured leaping up the hill on the way to winning the 2019 Porsche Club Speed Championship. The car also took fastest time of the day at Shelsley en route to the title.AUTHOR

Classic Porsches gathered for Porsche at Prescott. Front row cars include Josh Sadler’s famous VRC 911S, the 3.2-litre car of Jonathan Williamson/Laura Wardle, and LRP 73L of Matt Pearce.AUTHOR

I still believe that lower-end models offer the ‘purer’ drive. It is why I like the basic Cayman. If you want 500bhp+ and tyres with glue-tread, book a track day for your GT-something RS-Turbo-blower machine. Oh and I blame the late Herr Piëch for building a Porsche version of a Range Rover and ordering from upon high, the upright Cayenne. Designer Steve Murkett (under Harm Lagaay) apparently advised something sleeker, more Porsche-esque, but both were reputedly refused by the power of Piëch. But arguing with Piëch was, it seems, unwise.

Oh! But now we have the Cayenne Coupé after all.

If you are a Porsche purist, you may agree with some of my sentiments, but I urge you to take a wider view than purism or sectarianism, for Porsche could not survive in that sect, the sales were not there – just as they were not for Saab, or Citroën. It is all a strange paradox of circumstance and brand: Porsche had to survive and if that means today’s Porsche and then the rise of the Taycan and electric or hybrid drive – we had best adapt or be wiped out as dinosaurs of old design and old thinking. It is a horrible cliché, but we are, indeed, where we are.

To activate the Taycan’s on-board digital systems, you have to speak to it – sadly, the key phrase required is ‘Hey Porsche’. The question is, is it programmed to respond to ‘Porsch’ or the correct pronunciation of ‘Porsha’?

Even the 911’s defining rear-three quarters bodywork design – the fastback, ellipsoid rear side windows and flared rear deck and valance has been translated into the modern Porsches – even into the Cayenne Coupé. Porsche-speak now calls this amazing 911 design element – which has metamorphosed across fifty years of design leitmotif – a ‘flyline’ and turned it into marketing communications amid designer-speak to customers.

As I said, we are where we are. But this narrative talks in plain English and avoids corporate-speak.

And does not that defining rear end shape – the so-called ‘flyline’ – actually go back beyond the 911 to the 356 and even into Komenda’s pre-war Porsche designs? Just a thought…

This book is about Porsche factory cars, so there is no room, nor reason, to discuss non-Porsche creations, but I cannot let the efforts of the likes of Autofarm and Paul Stephens, and the different works of Singer, Emory, Tech Art, RUF, FVD Brombacher, RPM Technik and Magnus Walker go unmentioned. Each of these, in their own respective manner, has added to the Porsche legend with their modified Porsches. And have you seen the Jack Olsen 911 Special? 356 fans had best look away from the Emory Motorsports/Momo 356 ‘evocation’: this was a hot rod racer that mixed 356 and 964 parts in a very imaginative homage to mix-and-match Porscheism, built by an otherwise ‘classic’ Porsche expert in California – that other home to Stuttgart screamers.

A 356 Cabriolet sprints away in a classic Porsche moment with the hood up. Note the exhaust exiting in the over-riders.AUTHOR

There is much joy to be had in being a non-conformist Porscheist!

California dreaming is what happens to old 911s way out west beyond the great dividing-range of the Rockies. California accounts for 25 per cent of all American Porsche sales and has several of the leading independent Porsche specialists. In 1959 a Czech named Vasel Polak – who raced Porsches through to the 1970s – set up California’s first Porsche outlet. In California today, you must visit Rod Emory at Emory Motorsports, then go to North Hollywood and also Burbank, and drop by at TRE Motorsports and then at PRO Motorsports. Rob Dickinson (related to musician and pilot Bruce) is the man to talk to at Singer Vehicle Design, where fact meets a wonderful fantasy Porsche evocation – over 100 Singer Porsche ‘specials’ now sold. Bruce Canepa (ex-Porsche racer) is another California Porsche creator with a record of stunning ‘free-thinking’ Porsche output. Los Angeles is home to Magnus Walker – ex-pat British fashion designer who is the man and the money behind a collection of incredible modified/customized Porsches that have become very credible indeed.

All these ‘alternative’ creations capture the essence of the Porsche enthusiasm way beyond the ‘rules’ that apply in Germany and the branding guidelines that big auto manufacturers insist upon – even Porsche. Here in the alternative world is lateral thinking beyond the gates of remembrance.

For at these altar pieces to Porscheism can be found something different to a visit to an Official Porsche Centre. My local OPC and Porsche Classic outlet is superb, but corporate rules apply and egos seem to visit: we cannot, it seems, deny that Porsche has on occasion attracted some rather arrogant and newly enriched customers. But they will learn. For the real enthusiast is obvious, irrespective of income or status. It’s about the cars you see, not the VIP or ‘high net worth’ delusion of self-entitlement and bad manners.

There is even a Porsche enthusiasts club in Kuwait – yes, Kuwait – desert Porsches. It is the work of Yousef Fittani (and friends) who told Christophorus that ‘Porsche is my greatest passion’. Well, Yousef, you, me and thousands of others.1

Sadly there is no space in this book for the Porsche motor sport tales of Bell, Bellof, Mass, Stuck, Wollek, Ickx, Siffert, Elford, Tuthill, Attwood, Röhrl, Barth, Hurwood, Gregg, Holbert, Hermann, Dron, Faure, Fausett, Sadler, Larousse, Rodriguez, Weber, Tandy and so many more, but they too are all part of the Porsche legend, as are owners, club members and enthusiasts.

Fans of individual Porsche types, people of the Porsche tribes, may find their cars’ stories a touch truncated here-in, but this is what it says on the cover – a model-by-model guide that brings us up to Taycan date. By the time this book is on sale, the new 911/992-series may have finally been allowed a manual gearbox by the rulers of Porsche.

My family had an orange 911 2.2 on the driveway at home when I was a boy. I often wonder, was that car where I first learned that a Porsche is not just an inanimate lump of metal, but a living, emoting, sculpture on wheels that you can have a relationship with? I had best not fall into the trap of waxing lyrical over the wailing sound of the air-cooled flat-six, although even the most rational of grown men have – talk about a song of the sirens.

Having said all that, let’s not get too esoteric. This is the story of Porsche’s cars, and the ingredients therein. It is a privilege to get the chance to write a Porsche book and be given the space to expand from the norm to the forensic. I have no shame in declaring a love for Porsche and this book is an attempt to engage with several Porsche positions and come to a Porsche understanding – model-by-model.

Lance Cole

PORSCHE PRECURSOR

Ferdinand Anton Porsche (Snr): founder, genius and defining influence on the twentieth-century car design. His electric motor and drive hub/axle experiments of 1893–1901 seem set to have defined electric car dynamics, too, via the Taycan.PORSCHE

AN ELEGANCE OF FUNCTION

CHAPTER 1

PORSCHE PRECURSOR

THE PORSCHE ‘PROCESS’ is the critical ingredient that makes these cars something other than just cars. Perhaps more so than with many other marques today, the ethos of Porsche, the design language and the design research psychology of Porsche remain the essential core of a Porsche car and its appeal to the buyer and driver. The heart of the Porsche passion stems from one man and his legacy handed down across many decades through his descendants and dedicated followers. From Ferdinand Porsche came the engineering of design that led to that famous Porsche statement of ‘an elegance of function’. Throw in ‘designed for driving’ and the combination of the function of excellence amid the Porsche process, and we have the resulting cars.

Bohemia, Vienna, and Austro-Hungarian themes are writ large in the history of Porsche. All the 1947 Porsche 356 development team were Austrians – not Germans. Ferdinand Porsche ‘became’ German as did his cars, but old Vienna and all its cultural influences are part of Porsche, something many of today’s commentators and even some Porsche owners, know little of.

Those Porsche owners do sometimes fall into tribes; some are purists, some prefer the 356, and the 911 is a legend that has a dedicated following. Some Porsche fans (including the author) can admire the rear-engined Porsches yet at the same time, are fascinated by the front-engined Porsche story: the 928 suddenly seems a massive achievement in design terms and the 924 and 944 were vital to the continuance of Porsche AG.

Then there came the modern era, controversy, change and the new class of Porsche and new technology. Demands of marketing and finance led to cars such as 914 long before the 924 etc referred to above, then after a long gap, the Cayenne, Boxster and Macan; without them, the truth is that the 911 would not have sustained Porsche. Above all this lies ‘911’, but the truth is that Porsche is now about more than 911 – even though those magical numbers define a legend.

Before we journey through the cars of Porsche it is important to understand the thinking that lay within them and that remains a critical part of what is a modern, new Porsche.

UPON ENTERING THE COMMAND POST

When you climb into a current Porsche (or, indeed, an older one) the correctness of it all embraces you immediately: there is a tangible ‘feel’ and a purpose apparent. It feels like a tailored cocoon, perhaps even a touch military in its efficiency of cockpit purpose. The link to the past setting of such parameters is real. Everything falls to hand, to function: the seat is perfect, the design is classy. Nothing is too fashionable, little will quickly date. Only floor-hinged pedals are currently missing from the place they once occupied. Inside and outside lies Porsche Design – with a capital D.

We can only wonder what a Lutz ‘Luigi’ Colani-designed Porsche would have looked like, but his genius and ego, his uncompromising future-vision, would probably have been too much for the rigid rules of Stuttgart’s corporate hierarchy. But we cannot ignore the fact that a Porsche was, and remains, ‘biodynamic’ in its curves and ellipsis of form and function. Did the Boxster and the 996 subconsciously channel Colani? Some think so. And we know that Colani approved of the 928’s ‘biodynamic’ lines; sadly he was dismissive of the 911’s development in the 1970s and 1980s.

A shiny new Porsche can convey its heritage amid the brand and marketing-speak of today’s era. To understand how and why, we need to look under the bonnet of the story and its cars. For cast large upon Porsche and its vehicles are the personality and principles of Ferdinand Porsche, his progeny and his employees amid a distinct, defined, design research thinking.

Ferdinand Porsche was originally of Austria and of Bohemia, not of what we now frame as the Germany of the post-1871 and post-1918 restructurings of the old German States or Protectorates. Bohemia ranged in the west from today’s Bavaria, north to Poland, south to Austria and east to Slovakia via the Czech Republic. It was a place amid a time now modified by politics and conflict after the Weimar Republic and the Anschluss of 1938. Bohemia gave us many things in engineering including some of the great names of car design and automotive engineering: Austro-Daimler, Laurent and Klemin, Lohner, NSU, Praga, Rumpler, Skoda, Steyr and Tatra, to name just a few.

The reader may also be surprised to know that just as today’s ‘German’ Porsche was not German in its DNA or early home, neither was Bayerische Motoren Werke AG, as German as it appears today – the Munich-based legend that is Bavaria’s BMW was founded by three men and two of them were Austrians! Franz Joseph Popp, BMW’s founding engineer, was born in Vienna. Dr-Ing Max Friz was an engine designer, and Camillo Castiglioni was a Trieste-based banker; both men were brought in by Popp as he started BMW from its earlier Eisenach and Wartburg origins. Like Ferdinand Porsche, Franz Joseph Popp worked for Austro-Daimler in his early career, where he built aero-engines under licence from the Rapp Works.

Thus two of the three great names of southern German automotive history – Porsche and BMW – have Austrian roots, yet both were touched by another great marque: Stuttgart-based Daimler-Benz (Mercedes-Benz). Porsche worked for Steyr of Austria – so too did the other ‘great’ of car design of this era, Hans Ledwinka (latterly of Tatra fame), another Bohemian.

Hans Ledwinka was perhaps the leading automobile engineer/designer of Bohemia prior to the rise of Porsche: Ledwinka’s Tatra cars, later clothed in the ‘aerodyne’ bodywork of Paul Jaray (another Bohemian of Austro-Hungarian lineage) with rear-mounted engines and monocoque airframe-type body construction, set down an early marker for any rival to exceed. Perhaps only the French – Voisin, Gerin, Cayla, Lefebvre, and Bugatti – rivalled the talent of Bohemia in these early years of the motor car.

ELLIPSIS

British genius was slower to manifest upon the road and in the air: Sir Frederick Lanchester was, arguably, at this time the leading British exponent of aeronautical and automotive genius – he produced an elliptical wing and flight tests of it to prove its efficacy as early as 1894. This was years before Ludwig Prantl, and Ernst Heinkel made elliptically winged aircraft and claimed the credit – that was even cited as of origin to the Supermarine Spitfire in an error of massive historical proportions (the Spitfire’s ellipsoid wing was very different to Heinkel’s and was designed by a young Canadian genius named Beverley Shenstone). Elliptical and aerodynamic effects were soon to be the focus of German aircraft and car design and can be seen in Porsche output, too.

Even Ettore Bugatti was touched by ellipses and also by Bohemia, and made his first cars in Germany and painted them the German national racing colour of white, not the later Bugatti Blue. Northern Italians were also part of this great arc of engineering design that lay from Italy to Silesia, the remnants of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its centre of European history and artistic culture.

In 1951, when Ferdinand Porsche died, he was rated as the last of the great designers of the founding epoch of the motor car. He was defined alongside Bugatti, Daimler, Giacosa, Lancia and Ledwinka. Prior to his demise, there were decades of advanced thinking and design in the age when German, and notably Bohemian, innovators were the creators of the motor car.

Prior to 1910 British car marques were yet to make their true rise to dominance: it was French and German marques that dominated. Very early British cars and aircraft used French engines, or were entirely French designed and built. Amid the new German identity, there lay the effect of Austria and Bohemia and its inventors as they migrated to Stuttgart and Munich.

Bohemia was also the heart of early aviation and great advances in aerodynamics – Alexander Lippisch, inventor of the delta wing being of note. Great writers and great composers also stemmed from Bohemia. This land, now scattered amid the lines-on-the-map that define Poland, Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, was a cauldron of intellectual and academic talent. For some reason, a strain of creatives and engineering-minded men stemmed from the mountains, rivers, and valleys of magical Southern Silesia and Bohemia.

Vienna was Austria’s capital and was ‘Bohemian’ in every sense of the word. It bred fresh thinking of multi-cultural input – Berlin would later rival Vienna for its broad-thinking society and cultural freedom, at least until the Nazis came to power in 1933. Ferdinand Porsche was born in this crucible of genius in 1875 – exactly the correct time in history. Porsche was born into an Austro-Hungarian state amid a Germanic influenced community in a small village named Maffersdorf – then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, but today known as Vratislavice nad Nisou, in the Czech Republic. The nearest big town was Reichenberg (now Liberec). He was not high-born: he was the son of a metal worker, a tinsmith. It is possible that the name ‘Porsche’ is derived from eastern, Slavonic origins, but this does not necessarily indicate that Porsche was of Slav origin – many mixtures and modifications of names and origins were forced upon people as the map of Europe changed during the turbulent years between 1875 and 1914. A record of the Porsche name appears in East German regional records dating back to the fifteenth century, but Ferdinand’s family may not have been of this strain as they were from further south.1

Ferdinand’s great-great-grandfather Porsche came from the region of Reichenberg and Bohmisch-Leipa in northern Bohemia. As politics and war raged in the early years of the twentieth century, this area became part of German Sudetenland within the new Czechoslovak state that appeared after World War I. Porsche was not Czech, but Austro-German, yet had no choice other than to accept Czechoslovak citizenship as central Europe was reshaped. To deny it would have left Porsche as a passport holder of a restricted Austrian state that had been part of losing World War I and Porsche and his technological works would have been constrained by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. So it would be entirely wrong to label Ferdinand Porsche ‘the Sudetenland German’ as some observers choose to do – after all, Germany as it became, let alone Sudeten Germany, did not exist when Porsche was born. Thus the Porsche family had no interest nor part in the German nationalism that would soon be encouraged in the region after 1933 by the ‘new’ Germany.

The Porsche family men were artisan craftsman and highly valued by the local nobility. Ferdinand’s father, Anton was a tinsmith and his mother Anna Ehrlich was a local woman. The Porsche couple had five children but their eldest son died young, so it was the third-born child, Ferdinand, who was intended to take over the family metal-bashing business. But Ferdinand was obsessed by mechanical devices as a boy and soon focused on experiments with the new science of electricity and all its potential, in a series of teenage thoughts. Packed off by his parents to the local technical school’s evening classes, young Ferdinand soon had the family home rigged up with electric light via a generator and wiring that he had created and installed on his own. No other working man’s house in the village had electricity.

This is where Porsche’s analytical behavioural approach began. It really took off when his father let him enrol at the Vienna Technical College. Ferdinand was offered a job as an intern at the Bela Egger Company (which became the famous, Brown Boveri company), run by the Ginzkey family. Aged 18, Ferdinand Porsche went off to Vienna, which was how it all began.

By his early twenties, Porsche was running the Bela Egger company’s test laboratory but he soon joined Jacob Lohner & Co. in Vienna and went on to design the very early ‘electric’ cars for Lohner – who was ‘by appointment’ to Austrian royalty. It was a huge opportunity.

POLYMATH OR GENIUS?

How clever, how prescient, was Ferdinand Porsche? Was he some form of genius? Was he not both an engineer and an artist? He surely was a genius, a true polymath thinker of great vision. We should recall that while still in his early twenties, he designed, built and raced his first electric car and set a new record with that car. It was a car with an aerodynamically faired front. Ferdinand built a second electric car, for a Mr E.W. Hart of England and, by 1902, had built the Lohner-Porsche ‘mixed drive’ racing car, soon followed by another variant (the ‘Chaise’) that had the world’s first true working front-wheel-drive configuration, and one driven by electric hub-motors: this was the Radnabenmotor, an idea that Ferdinand had thought of in 1899. Today’s electro-drive and hybrid-drive thoughts, defined as a futurism by Ferdinand circa 1900. At the great exhibition held in Paris in 1900 Herr Lohner said of his designer Ferdinand Porsche: ‘He is very young, but he is a man with a big career before him. You will hear of him again.’

Ferdinand was not just a technical thinker, he was ‘natural’ behind the wheel as a gifted and fast driver, so right from early days he developed cars that drove correctly – driver feedback from the components, controls and performance all becoming dominant factors. Ferdinand soon established a driver’s record on the 10km road-race section of the Semmering road near Vienna, a long climb up a hill with tight bends and varying surfaces. ‘Semmering’ was a known, true test for any of the early cars and Porsche mastered it, setting his record on 23 September 1900 with a time of 14 minutes 52 seconds, officially recognized as a record for all types of ‘electromobiles’ – electrically powered vehicles.2

Porsche’s first racing car of 1900 was electric and set a new record for electric carts at Semmering in late 1900. Note the aerodynamic front-shroud.PORSCHE

The Lohner-Porsche mixed-drive car of 1900.PORSCHE

He had a real desire to produce a smaller, more efficient car, not a land-yacht or an imperial barge, which had become something of a car design fashion by 1910. Unlike most other cars of this era, which were open-bodied or without a body at all, Porsche clothed his early cars in a skin with a faired-in aerodynamic shield at the front, and with side and tail panels soon to follow. So were set the runes of Ferdinand Porsche’s design thinking and driving needs, all of which would manifest themselves in Porsche cars – then and now. Like so many innovators, he did not follow the rules: he also liked early aeroplanes and the little-known issue of airflow was of note to him.

Having made the headlines with his efforts for Jacob Lohner’s cars (as Lohner-Porsche), Porsche’s name became high profile and he was placed on the military reserve instead of having to do military national service, on the orders of no less than His Imperial Highness Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The tinsmith’s son had risen through society.

By the time of World War I, Porsche was creating gun carriages, powered ‘mixed-drive’ vehicles, trains with hub-motors to ensure lightness by removing the need for a heavy separate locomotive, and other devices for the Austrian military. Ferdinand also dreamed up a horizontally opposed engine that was almost a flat-type but which had its cylinders lying at an angle in a curious X-layout.

Back in Vienna of 1900–14, Porsche designed fire engines, buses, tractors, gun carriages, drive-mechanisms, chassis, streamlined fairings and a host of others. He did, however, feel constrained by his employment at Lohner (where he had spent a lot of money on research) and at the age of thirty joined the famous marque of Austrian-Daimler (later Austro-Daimler) in Wiener-Neustadt, south of Vienna. There was the biggest car-making factory in all of Europe, run by Paul Daimler – son of Gottlieb Daimler of Stuttgart.

In World War II, Porsche would design the lethal and much-feared ‘Tiger’ tank, the Maus (‘Mouse’) heavy tank and the amphibian VW Schwimmwagen and court controversy as a result – not helped by perceptions of his role in the development of the Volkswagen ‘Peoples Car’ at Hitler’s direct orders. But Porsche was not alone in working for the Nazis – many Germans had to do that.

AUSTRO-DAIMLER & JELLINEK

As technical director at Austrian-Daimler, many doors of thinking and realisation were now open for Ferdinand and he pursued car design at the leading edge of its development years. He quickly turned out a modified Mercedes with 85bhp racing car with hub-drive. A Porsche-designed 250bhp SSKL model also impressed observers.

The 1921 Austro-Daimler Sascha with an engine of 1,100cc – driven by Neubauer to 88mph.PORSCHE

Austro-Daimler grew from the engineering company originally founded by the Fischer brothers in 1865 and would grow into Daimler-Benz AG. Like Herr Dr Porsche, Herr Daimler and Herr Benz were not aristocratic, being the sons of a baker and a train driver, respectively. The Jellinek family were backers of the Austro-Daimler and Emile Jellinek’s daughter Mercedes would give her name to the marque of Mercedes via a link from Daimler to Stuttgart. In 1903 Emile was granted the legal right to call his family named business Jellinek Mercedes. He added the Mercedes name to the trademark for the German Daimlers that he imported to Austria: so was born the idea of Mercedes-Daimler that became Mercedes-Benz.

The Daimler versus Benz story had to be acted out, but Mercedes gave her name to the subsequent marque. But it was Jellinek money within Austro-Daimler that helped Ferdinand Porsche create the small ‘Maja’ 30bhp car (an elder Jellinek daughter, Maja, had given her name to the Porsche-influenced car of that name). Then came a more adventurous design, a 32bhp, 4-speed car with chain-drive (later shaft-driven): the Emperor of Austria bought one for its hill-climbing abilities and long range.