33,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

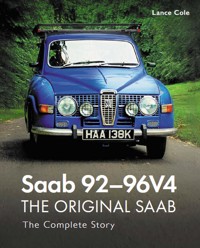

Launched in 1949 as the 92 before evolving into the 93, 96 2-stroke and 96V4, this car was in production for thirty-one years. Attracting global admiration and sales, it also excelled in motorsport and by the early 1960s was the most successful rally-car in Europe. A decline in sales in the 1960s was reversed with the launch of the 96V4 which resulted in its success continuing into the 1980s. With over 200 archive and colour photographs, this book provides a new description of the Saab company's original car and includes detailed biographies of important Saab figures and extensive discussion of the engineering and design decisions that made the car such a success. There is coverage of the original Saab story in North and South America and a comprehensive review of Saab 92, 93, 96, motor sport history. Full technical details and specifications and tuning details are given and finally, there is a chapter on owners' experiences and Saab veteran's recollections.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV & Spider

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, 5, 6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Austin Healey

BMW E30

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupes 1965–1989 2000C and CS, E9 and E24

BMW Z3 and Z4

Classic Jaguar XK – The Six-Cylinder Cars

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta: Road & Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar F-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 & 2, S-Type & 420

Jaguar XJ-S The Complete Story

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Land Rover Defender 90 & 110

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

Lotus Elise & Exige 1995–2020

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Fintail Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class 1972–2013

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes-Benz SL & Noakes SLC 107 Series 1971–1989

Mercedes-Benz Sport-Light Coupé

Mercedes-Benz W114 and W115

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126 S-Class 1979–1991

Mercedes-Benz W201 (190)

Mercedes W113

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

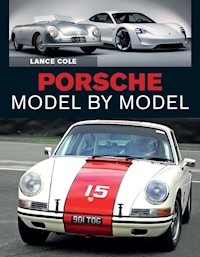

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera – The Air-Cooled Era 1953–1998

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos 1974–1996

Porsche Carrera - The Water-Cooled Era 1998–2018

Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979–2019

Range Rover First Generation

Range Rover Second Generation

Range Rover Sport 2005–2013

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800 Series

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover P6: 2000, 2200, 3500

Rover SDI – The Full Story 1976–1986

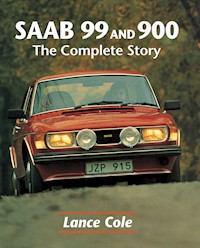

Saab 99 and 900

Subaru Impreza WRX & WRX ST1

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire and GT6

Triumph TR7

Volkswagen Golf GTI

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

First published in 2022 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Lance Cole 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4018 0

Cover design by Sergey Tsvetkov

CONTENTS

Dedication & Acknowledgements

Timeline

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 ORIGINS: WINGS TO WHEELS

CHAPTER 2 URSAAB: DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER 3 92: SOUL OF SAAB

CHAPTER 4 93: ESSENTIAL SAAB

CHAPTER 5 95: ESTATE CAR SAAB

CHAPTER 6 96: DEFINING SAAB

CHAPTER 7 SAAB 96 V4: CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

CHAPTER 8 SUPER SPORT: MR SAAB AND MOTOR SPORT MOMENTS

CHAPTER 9 BUYING AND RESTORING A CLASSIC SAAB

References

Bibliography

Index

DEDICATION &ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DEDICATION

To all the men and women of Saab’s cars and notably to my personal heroes: Gunnar Ljungström, Sixten Sason, Björn Envall, Rolf Mellde, Josef Eklund, Erik Carlsson, Stig Blomqvist, Robert Sinclair, Ingvar Lindqvist and Squadron Leader Robert Moore DFC.

Gentlemen, thank you for your brilliance and the Saabs that resulted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Erik and Pat Carlsson, Chris Partington, Alex Rankin, Robin Morley, Graham Macdonald, Chris Hull, Martin Lyons, Chris Redmond, David Dallimore, Chris Day, David Lowe, Alan Sutcliffe, Mike Philpott, Tony Grestock, David Lowe, Arthur Civill, Jim Valentine, Dave Garnett, Richard Simpson, Iain Hodcroft, Ian Meakin, Ellie and Shaw Wilson, Peter and Janet Turner, William and Bridget Glander, Jean-François Bouvard, Joel Durand, Alain Rosset, Tom Donney, Bruce Turk, Jim Valentine, Drew Bedelph, Steven Wade, Gunilla Svensson, Krzysztof Rozenblat and the Rozenblat Family Foundation, the late Etienne Morsa. A salute to David Hines, Ken Coe, Andrew Mason, Vernon Mortimer, Don Cook, Alan Lawley (and respective wives where appropriate) for all their work at the Saab Owners Club GB and its publications in the early 1960s and the 1970s. Motoring noters to thank include: Steve Cropley, Hilton Holloway, Mark McCourt, Richard Gunn, James Walshe. Specific thanks go to the Saab Club GB, Saab Enthusiasts Club, Saab Club Sweden, Saab Club Australia and, of course, Saab Car Club North America and its Nines magazine.

A salute to the wonderful Club Saab Uruguay and Alberto Domingo, and to the family Abeiro. A further salute to the Buenos Aires Saab Club and Charles Walmsley. With thanks to: the Västergötlands Museum, Sweden; the Saab Car Museum (Gunnar Larsson, Roy Beaufoy, Albert Trommer, Per-Olof Rudh, Peter Bäckström, Gunnel Ekburg); the Saab Veterans Association (Saabs Veteranförening); Svenska Saab Klubben/Bakrutan magazine and editorial team; Swedish Motor History Association (Motorhistorika Sallskapet i Sverige) and Per-Borje Elg; the Marcus and Amalia Wallenberg Memorial Foundation. Acknowledgements also to: The Daily Telegraph; The Independent; Classic Cars; Autocar; Teknikens Varld; Saab Cars magazine. With thanks to the many others who have taught me about Saabs or published my words on Saab.

I would particularly like to thank Alex Rankin, Robin Morley, Chris Redmond, Martin Lyons, Mike Philpott and Mark McCourt for all their support and kindness and in the research for this book. A salute to my tutors and mentors at KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, and at Qantas, for teaching me to think, to fly the plane and never be seduced by the computer and the complacency it engenders.

Note: The author Lance F. Cole has no connection to ‘Lance Cole Photography’, its entity, website or any claims or actions made by such. The author has no connection to social media claims of religious or political content made by any other ‘Lance Cole’ entities as known to be extant.

TIMELINE

1937

The defining amalgamation of the main Swedish industrial engineering companies into a SAAB group on 20 April 1937, locating aircraft production and engineering output at Linköping and using offices of Nohab Company.

1939

SAAB of Linköping establishes its first main engineering works and offices at Trollhättan to include a new airfield, and expands the design office at Linköping. Marcus Wallenberg oversees the final merger to create the greater amalgamated Saab entity, which is completed in 1939.

1940–43

Saab’s first three aircraft emerge, notably the Saab-designed twin-boom S21/J21.

1944–5

First discussions about a Saab car from late 1944. The design team includes Saab aircraft designers. Ljungström and Sason produce sketches of the car.

1946–8

Twenty four pre-production cars including three prototypes.

1949

First final specification 2-stroke Saab 92 production-series car leaves factory on 12 December.

1950

The dealer Philipson makes the first official customer deliveries from 16 January.

1953

Saab 92B launched with boot aperture, larger rear window, and relocated fuel tank.

1954

Further revisions as B/2 specification.

1955

Saab 93 announced as heavily re-engineered for 1956 model year with new 3-cylinder engine.

1956

Last 92B cars built late in 1956 for sale into early 1957.

1957

Saab 93B announced.

1958

Saab 93 Granturismo 750 launched: becomes ‘GT750’.

1959

Saab 93F and 95 estate car announced: mass volume sales begin in 1960.

1960

Saab 96 developed from 93B: GT750 now with 96 body.

1962

Saab 96 850 Super Sport launched, known in the USA as the GT850/Monte Carlo by 1964.

1966

Restyled Saab 96 launched with major specification revisions: 850 becomes Super Sport Monte Carlo in all markets.

1967

Saab 96 V4 1.5-litre announced alongside new 95V4 option. 2-stroke sales continue for more than 12 months, notably in the USA.

1968

Bodyshell modifications with larger front windscreen aperture.

1969

Saab 96 V4 revised with new styling and specifications.

1970

Saab-Scania and Valmet Oy collaborate to begin production at Uusikaupunki, Finland.

1971

US market 96 V4/95V4 engine offered as 1.7-litre low compression type.

1975

Saab 96 V4 1.7S Rally Special Edition on sale. Further exports and domestic market special editions of the 96 V4 follow as ‘Souvenir’ and ‘Jubilee’.

1976

Saab 96 with major revisions and 5mph ‘impact’ type cellular self-repairing bumpers.

1978

Saab 95 estate withdrawn from model line-up.

1979

Final 96 V4 cars, all built in Finland.

1980

Last 96 V4 leaves factory driven by Erik Carlsson in January. Final sales ex-showroom continue across Europe into mid-1980.

INTRODUCTION

Original Saab – an engineering excellence and elliptical ethos

Mainly, I think it is due to a common philosophy. It’s a little difficult to fully explain, almost as difficult as to why a new melody, just a few notes of music, suddenly catches on to become very popular ... I think however that our design and engineering philosophy was right, from the start. We considered it very important to design a robust and safe car, having a high degree of refinement. The car had to stand out above the rest and be appreciated for its practicality, performance and overall quality level.

Tryggve Holm, engineer and Saab CEO (1950–67), discussing the reasons for the success of the first Saab car (1961)

There are some cars that touch the soul, cars that are so inherently correct and so ‘right’ that their size or engine capacity seems utterly irrelevant. The brand is not the point: the car and how it was engineered and designed, and consequently how it drove, was (and remains) the point.

Erik Hilding Carlsson’s Saab 96 2-stroke tribute car seen heading the Saab convoy at his memorial service in 2015. Erik was Saab and there is nothing quite like a red rally Saab ‘stroker’.

Saab 92 early model (without boot/trunk lid): this is the grail-cup of early Saab and the ‘face’ of the car says it all. Tony Grestock’s amazing 728 XUR has to be one of the rarest and most valuable Saab’s in the world. Tony drives it as intended, educating people about the magic of Saab.

Among the small number of cars that fit this description in the last half of the automobile’s greatest century were the Saab 92 and its direct offspring, the 93 and 96 (as 2-stroke cars), and then as the 4-stroke cycle 96 V4.

Before everything became computerized, digital and electric, at a time back when man’s mechanical interaction with his machines was the point of the mechanism, the original Saab car was, like a few others, a direct, visceral, mechanical driving experience utterly devoid of the effect of consumer ‘clinics’, ‘marcomms’, fashion, foible or celebrity opinion through self-proclaimed ‘influencers’.

In the early 1960s the little Saab was the most successful rally car in Europe, irrespective of price or size classification. Look at the fuss Ford, followed by Audi, made in later decades when their cars achieved such status: Saab were entirely justified in their self-proclaimed brilliance.

The Saab car or ‘Bil’ (‘bil’ is Swedish for car) was, like the original Porsche, the original Citroën or the original Lancia (to mention a few other candidates), an act of adult engineering design and driver delight all wrapped up in a ‘pure’ car. Grown-ups were in charge when creating the Saab car, not corporate-speak lemmings with an eye on passing trends and quickly dating fashion, expressed in ‘new-speak’ Orwellian design languages, meaningless clichés and pointless phrases. Saab never touched such things. This is why Saab’s cars were so very real and utterly timeless, untouched by the dating of fashion. You cannot really say that about a Ford Cortina, a Honda Civic or a Morris Marina. The compromises of coalesced ‘group-think’ were not required at Trollhättan.

From its initial ‘92’ iteration, then to becoming the 93, and through to its 96 2-stroke and 96 V4 forms across the thirty-one years it was on sale, here was a car that was so correct, so clever, that it excelled on the world’s stage as a family car and as a race and rally car too. A car that was a useful hold-all you could go camping in, yet also a coupé that raced and rallied to the top of the world’s motor sport stages. Indeed, in the 1960s Saab Great Britain Ltd ran an advert citing such dual, weekend and workday use of a family Saab as both a rally car and family driver as owned by the mysterious ‘George’. Apparently George had a sports car of his own, but never used it, instead preferring his wife’s 96.

This original watercolour artwork for the 1950 brochure was painted by Sixten Sason’s own hand. Green paint ruled.

The Saab 93 on display in the Science Museum, London, is a symbol of its importance.

The little Saabs are ‘real’ cars for real driving and real fun. Rev a 2-stroke to 7,000rpm and let it fly and you will get the message. Yet do not forget the sonorous V4 and its sheer throbbing urge. Today these older Saabs are the subject of huge interest and have a growing following, matched by rising prices. As always with the 92, 93 and the 96s, a dedicated bunch of Saab enthusiasts who are clearly emotionally attached to their steeds remains the core of the movement worldwide.

If you want to know just how famous these Saabs became, consider the fact that it was not just in Sweden where the Saab 92 and 93 appeared on official postage stamps. In the unlikely location of Grenada, the post office issued a $2.00 stamp with three views of a large red 1963 Saab 93. The stamp was part of Grenada’s centenary celebrations on 1 June 1988: but why a Saab? Saab really does get to parts that other cars do not.

In the Science Museum, London, there is a display of cars cited as being of importance in the history of the motor car, and among these is a 1956 Saab 93.

The little Saab may have been Swedish, but there were many ingredients in its DNA, with influences from Czechoslovakia, Italy and France. Its design was new yet evoked themes of 1920s ‘Aerodyne’ engineering from airships, to locomotives, to yachts, to cars. Even Paul Jaray and the Tatra cars he created for Hans Ledwinka get a citation in the annals of Saab 92 design.

Intriguingly, the 92’s chief engineer Gunnar Ljungström, although Swedish and essentially an aircraft designer, had some of his initial engineering training in England. He was also a railway enthusiast and a yachting fanatic, and some degree of knowledge transfer is obvious. Of interest, Gunnar’s father Fredrik had also influenced railway locomotive design and other aspects of Swedish engineering, including yacht hulls and sails.

Karl Erik Sixten Andersson (later known as Sixten Sason) was Saab’s first chief designer/stylist. He had trained in France and toured Europe in a quest for design. He was one of the forerunners and founders of the movement of international renown that today we recognize as ‘Swedish design’. Sason’s influence at Saab and upon Swedish design is far deeper than many people realize and this book contains a detailed tribute to his life and works.

Rolf Mellde was a young engineering enthusiast, inventor, rally driver and engine tuner who joined Saab in 1946 and hugely influenced the first Saab car and later models. The often forgotten Olof Landbü was an experienced 1930s rally and trials driver. As lead test engineer/development driver, he was the first to test the new Saab in 1946–8 and guided Mellde in the early days: Landbü drowned in a non-car-related accident in 1948 and consequently Mellde’s role expanded.

Josef Eklund became Saab’s 3-cylinder, 2-stroke engineering genius for the 93 and 96 2-strokes, helping to produce a design that one of his colleagues, Dick Ohlsson, summed up to the ‘Save Saab’ campaign at the time when Saab was fighting for its survival in 2011: ‘There’s something magical about Saab.’

As a tribute to Stig Blomqvist, the hero of Saab’s second rally generation, Graham Macdonald took a rally specification V4 with American-type headlamps and recreated pure heroic Saab glory. It is now under new ownership and soon to be seen on the historic events calendar.

In the first Saab with wheels not wings, there was to be found a small, exquisitely engineered, northern European sporting car that was something genuinely new. It was not a basic ‘people’s car’, but neither was it a conservative or middle-class saloon of upright values and appearance: it was transverse-engined and employed front-wheel drive long before the Mini. The Saab pioneered 2-cylinder and then 3-cylinder power in the mass market decades before today’s smaller petrol engines of ‘Eco’ fame.

The little Saab drove with style and sensation, with true feedback and with superb levels of steering and dynamic intuition. This car could even traverse rutted snow, ice and mud in off-road conditions thanks to its flat under-floor, and go on to toboggan its way across roads and rally stages that would stop rear-wheel-drive cars in their tracks. Or the Saab could be a family hold-all and daily driver.

Sometimes Saab’s engineers and designers went against their senior management’s conservatism. Secret or special projects were run internally by people like Mellde and Eklund, only for such ideas to prove successful and to effectively save Saab in the early 1960s at a point when the board’s pervasive 2-stroke ‘obsession’ was causing sales to wane. The special rebellious Saab spirit had a Swedish term ‘Saabandan’, meaning to be daring and go against orders.

There are many reasons why the Saab car company (not the aerospace company) died. More than one hand was to blame and solely citing General Motors (GM), or criticizing Mr Müller, is far too easy and too simplistic, although GM’s stewardship raised many questions that not even Bob Lutz and his talented team could manoeuvre around, rebadging Subaru and Chevrolet cars as Saabs in a desperate act of ‘badge engineering’. One of the key reasons Saab failed, yet a reason so often overlooked, however, was its own utter failure to reinvent its core, key car: the small Saab that as the 92 to the 96 had launched Saab, made Saab, and which for decades was Saab.

The point when Saab abandoned its roots in a small, sporty, intelligently designed cheaper car was when the company lost the opportunity to reinvent its brand, its marque equity, its ethos and its values, which were rooted in a defining ‘core’ car that would create high volume production number profits.

Even the most dedicated Saab enthusiast might have to admit that the company was so wrapped up in doing its own Saab ‘thing’, with all the engineering quality inherent in that status, that Saab was partly the author of its own downfall. Is this a dreadful thing to say? Maybe, but many Saab veterans believe it to be so. Some rival car makers thought that the Saab car was too high quality, but at Saab you did not think like that: quality and the effort to strive for it could never be too high. How did such a device get to be so ‘right’ and of such high quality from the word go?

Curiously, back in 1949, despite the very advanced design of its first car, some of Saab’s upper management displayed an innate conservatism that would later create tensions with those who wanted to expand – perhaps too radically, at the other end of the corporate behavioural spectrum.

Yet other car companies correctly reinvented their ‘core’ car icon and brand equity: imagine if Saab had reinvented the 96 as a VW Golf crossed with an AlfaSud injected with Saab DNA. What a car that could have been.

But no, long before Fiat, GM or Victor Müller got their respective hands on the levers of power, Saab chose to go up market. There were many correct reasons for this decision, yet it seemed strange indeed to abandon the vital, founding, core model range and brand equity that was the 92, 93 and 96.

I suppose it was all about money and production unit volume (or the lack thereof), and tough choices had to be made with one hand tied behind the corporate back. The Saab 96 sometimes just about touched 100,000 units a year, but Saab struggled to make enough cars to earn the profit to sustain itself. It was left to Volvo to produce two smaller cars (the 340 and 66) to fill the void created by Saab’s decision to ignore that market sector.

The truth is that Saab’s later cars would not have been born without the Saab 92–96 story, yet it was the eventual move upmarket that led to the death of that early original manifestation of Saab and what many now specify as ‘Saabism’. Swedish car buyers, and those in other markets, soon turned to other small- to medium-sector cars.

Today the old Saabs, which some contentiously describe as the ‘real’ Saabs, have a massive following. Describing them by such tags as weird or quirky simply reflects jealousy or the blinkered vision of conventional minds (a later Saab advertising strapline told you to ‘move your mind’).

Saab fans, sometimes known as ‘Saabists’, apparently suffer from ‘Saabism’ and it is said that they fall into three categories: fans of old original 2-stroke Saabs 92–96, as well as 96 V4 fans; then comes the followers of the developed 99 and 900, which still encapsulated ‘Saabism’; and after that are the enthusiasts of the much later Saabs right up to 2012 and the death of Saab as a carmaking brand.

A curious emotional bond infects the Saab fanatic, such as the respected veterinarian Chris Day, who had a yard full of old Saabs. Chris raced a 900 and restored an old 92, transporting his Saabs on a blue Scania-Vabis truck and inspiring many with his Saab enthusiasm.

The early organizers of the Saab Owners Club of Great Britain in the 1960s and 1970s showed huge commitment and much humour in its publications: ‘Bengt Krankshaf’ was the alter ego of Vernon Mortimer, who developed the club’s Saab Driver magazine.

Many years back, another big Saab fan was Tony Percy, who headed the Saab Owners Club GB in 1984. He owned two 96s, a 95, a 99EMS and later took care of the ‘SaaBSA’ motorcycle, a home-built design devised by Ray Pye in 1975 that combined a Saab 841cc triple, a BSA Rocket frame, a Triumph gearbox, a Vincent primary chain and a BMC 1000 radiator. Former Saab Motors USA director Robert Sinclair rode the ‘SaaBSA’ for a while in the 1980s. It then went through several owners before returning to Great Britain. Such is the free thinking of the Saab fanatic.

Sinclair was so admired by American Saab dealers that when he retired as president of Saab-Scania America/Saab USA, all 130 American Saab dealers clubbed together and bought him a restored Sonett II ‘stroker’ as a retirement present.

Also in America are the respected names of old Saab expertise led by the likes of Tom Donney, and Bruce Turk, who has been described as America’s most obsessed-with-Saab man! Chris Moberg has a Sonett and is fascinated by 2-strokes. Mike Grieco, of Grieco Brothers in New Jersey, seems to have got the old Saab collecting bug quite badly. The famous Saabist and nuclear physicist Walter Kern (of Saab Quantum fame) also built (with David Homer) an electric-powered Saab Sonett in 1975.

Members of the national Saab club in Japan own both the newest and the oldest Saabs in its membership, including a 96 V4 that lives in Tokyo. A representative fan of all things Saab among these was the an aviation technican and classic Saab owner Kazumoto Yabe. The German love of old Saabs thrives across northern Germany and even touches the hallowed turf of Swabia and Bavaria. Not surprisingly Saab still has a strong presence in Denmark.

The same goes in Africa (a dark green 96 exists in fine fettle in Tanzania), America, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, France, Poland, Portugal, the Netherlands and Norway – everywhere seems to have a family of Saab fanatics. As a Saab advertisement stated: ‘The Saab Spirit: Some people have it.’

The Saab Club of Australia has individual State sections and Aussies all over the nation love old Saabs. A decade ago I flew to Tasmania to meet Steven Wade, who founded the world’s first Saab blog and went on to Saab social media fame. Even the Captain of the Qantas 747-400 owned an old Saab. On my visit Wade introduced me to geologist Drew Bedelph, who has a warehouse-sized collection of early Saabs tucked away in this forgotten corner of the world.

Purists might disagree, but this heavily modified 96 captures the spirit of Saab sport and modification.

On my last foray to Australia, not only were there dozens of Saabs on Tasmania, more were to be seen on the ‘big island’. Way out beyond Alice Springs, on the way to Mount Sonder in the Glen Helen Gorge amid the West Macdonnell ranges, I found a property with a sun-bleached and faded old 96 that might once have been pale blue but now was almost white, resting out its dotage in the red dust driveway to a homestead. Apparently it still ran and was used for local runs – ‘local’ being anywhere within a hundred miles. A shopping trip to Alice Springs in a near sixty-year-old Saab? How normal.

On the twin islands of New Zealand there is a massive Saab subculture and up to a dozen Saab 2-strokes and V4s are currently active there. Head down to the bottom of South Island and you might bump into a 96! Saabs can be found in the islands of the Pacific too.

Reflections on Saab: a 96 captured in a 92’s hub cap.

Of all the Saab outposts, imagine seeing a 96 V4 in Korea in 1970: a regular sight there driving up into the de-militarized zone between South and North Korea was the 96 V4 of the Swedish Ambassador, which was the only Saab in Korea then and for years afterwards.

Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands once owned a 1958 Saab 93, as did the Swedish royal family led by Prince Bertil, starting with a Saab 92; the Danish royals followed their example. The famous British comedian Eric Morecombe ran a 96 V4 and a 99 Turbo, and then a 900 Turbo. Ernie Wise also had a 96. The actor and thinker Stephen Fry once owned a Saab. The wrestler Jackie Pallo drove a 96 V4 and was the first president of the Saab Owners Club of Great Britain.

What else would Raymond Baxter, Britain’s much missed broadcaster, writer, thinker and ex-Spitfire pilot, drive but a Saab. His friendship with Robert Moore, who headed Saab GB and happened to be a former Hurricane and Tempest fighter pilot, might just have influenced Raymond’s choice. Baxter (as well as Erik Carlsson’s co-driver Stuart Turner) was a member of the curious Ecurie Cod Fillet (ECF) rally team and it is said that an ECF decal was on Erik’s Saab when he (with John Brown) won the 1961 RAC Rally, but Saab peeled it off before the car arrived at the winner’s podium.

Bruce Turk, possibly the most obsessed Saab enthusiast in the USA, has a barn full of early Saab beauties ranging from the 92 to the 96, including a 93, 95 and Sonett. It is Saab heaven for collectors.

Classic Saab profile as the Sax-O-Mat equipped ‘stroker’ gets going.

A last-of-the-line, Finnish-built 96 V4 showed off the updates to an original bodyshell first created in 1949.

Visit Buenos Aires or Montevideo and you may spot Saab 92s, 93s, 96s and 99s on the streets, some of which were built locally as officially sanctioned South American Saabs. A plan to manufacture Saab cars in Brazil came to nothing (even though a Brazilian airline named VASP operated Saab-Scandia airliners for decades), but a Uruguayan-built Saab materialized after ten Saab 92s were shipped to Uruguay in 1952 and eighty were shipped to Peru. Several found their way up to Venezuela and down to Chile, where 93s and 96s can still be found rusting away in glorious peace. Havana, Cuba, boasts a bright yellow 92 with some non-standard modifications too. Saabs were sold in Ecuador from 1960 and the local concessionaire Marco Baca and his brother both raced Saabs (including a GT750) in local Ecuadorian events.

In Uruguay, where Saabs were being locally built in the early 1960s by the Automotora Company, its director, José Arijón Rama, raced a 96 Sport both in Uruguay and in Argentina. Héctor Marcial Fojo was the Saab South America ‘name’ in a 96 Sport with co-driver Nestor Uccellini.

The principal pillars of Montevideo’s Club Saab Uruguay, which was founded in 2008 by Alberto Domingo, are currently Carlos and Juan Abeiro. Alberto has run a Saab for fifty years, and he and his wife career around in their little red Saab. If we can agree that Alberto Domingo is our Saab hero in South America, then are the Abeiros the torch bearers for Saab in South America?

Besides Uruguay, there is also the Club Saab Argentina, which I first encountered when hearing about Buenos Aires resident Charly Walmsley, who has owned a lovely black 92B for more than forty years – one of two 92s and several 93s seen running around the wonderful city of Buenos Aires for decades.

In 2008 Walmsley’s other Saab, a red 96, and several other early Saab owners and their cars came together as the (now defunct) Grupo Saab Rioplatense (‘Saab Group of the River Plate Area’) to take part in an historic event in tribute to forty years of the Uruguay 19 Capitales rally, joining forces to create a team of three Saab rally cars, including two 96s, to compete in the 2008 re-enactment.

Erik Carlsson was a passenger in Walmsley’s red 96 when he visited Argentina and Uruguay in the 1990s. The great Argentinian driver Juan Manuel Fangio is said to have driven a Saab 96 and ‘got’ what the car was all about. (For more on Saabs in Argentina and Uruguay, seeChapters 3, 4 and 6).

An early 96 ‘long-nose’ captured low down to show off the lobed styling and revised front grille and lights.

From 92 to 96, the Saab sculpture retained its unique shape, scale and stance.

Perhaps less well known was the involvement of Saab and its designer, Sixten Sason, in the emergence of the globally admired Swedish design movement, providing key support. In the 1950s and 1960s Swedish design topped the world, being innovative and broad in its reach and details, as well as being of the highest quality. From cars to glass, furniture, chairs and architecture, and beyond to areas of interior, exterior and industrial design, fabrics, colours and consumer goods, Swedish design had an effect far beyond its domestic scale. Today we have ‘Scandi Design’ as an enduring legacy and Saab had a hand in its orgination. Saab’s story, therefore, is very much one of design mixed with engineering in a functional yet stimulating manner.

As a young designer I was fortunate enough to contribute something small to Saab design. In this book I have tried to convey my love of Saab’s contribution to the sheer brilliance of Swedish design, setting down the story of the original Saab, an icon, a true hero of an age of the automobile that has passed. Today’s digital highway has little space for such ingredients from the great epoch of the motor car prior to the 1980s. In Saab lay the difference: here we found the true Saab design language and the Saab philosophy.

Saab is sometimes written as Svenska Aeroplan Aktie Bolaget, but in correct Swedish it is Svenksa Aeroplan Aktiebolaget.

Saab was also part of the social science of Sweden and forged its relationship with its workforce and the towns where they lived. Today the wonderful Saab Museum and the Saab Veterans Club preserve historical documents that outline the relationship of the Saab ‘family’ and its workers through a form of social contract within Sweden’s advanced societal structure that, at that time, was possibly unique in Europe.

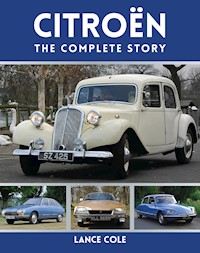

This book has taken many years to research and is my attempt at a detailed yet accessible history of Saab’s first car and, crucially, all the factors that created both it and Saab as not just a company, but a philosophy. Apart from Porsche or Citroën, I can think of no other carmaker with such a fascinating personality construct.

Here is the story of the speedy little Saab that so many loved as the ‘svenska bil med flygplansqvalitet’ (‘the Swedish car with aircraft quality’).

Lance ColeVilla Saab

CHAPTER ONE

ORIGINS: WINGS TO WHEELS

Although the Saab 92, launched in 1949, was Sweden’s first mass production front-wheel drive, safety-built and aerodynamically effective small car, Volvo had actually produced cars from 1927, starting with the ‘Jakob’ OV4 car, but these were rear-wheel-drive devices influenced by American designs. Dig deeper, however, and you will find that the history of Sweden’s first ‘car’ goes back a further three decades.

The origins of engineering and industrial design in Sweden began with railway locomotives, rolling stock, commercial vehicles and aircraft. Trollhättan was to become ‘locomotive city’ and later the home of Saab’s car production, while nearby Linköping was focused on aircraft; both towns would become manufacturing bases during the second half of the twentieth century.

The earlier attempts at Swedish car production were overshadowed by the manufacture of heavy goods vehicles, buses, and various engines and machines. It was these industries that laid the foundations of knowledge and aircraft design, making possible the rise of production facilities.

The first recorded Swedish-designed motor car and engine can be credited to Gustaf Erikson in 1897 and the design was then refined through to 1901 and beyond. This car and the early Swedish trucks and buses of the era were produced by manufacturers who would, three decades later, amalgamate to become the Saab Company. Erikson’s ideas, undertaken in collaboration with Peter Pettersson on behalf of the Vabis Company, would then contribute to the first cars built by Scania-Vabis.

This very rare artwork by Sixten Sason shows off his idea for a more upmarket version of the original 92 equipped with American-style chrome and faired-in headlamps. A case of future-vision unrequited.

The name Vabis is an acronym of Vagnfabriks-Aktiebolaget i Södertelge Company (with a different spelling of the placename Södertälje) and was applied by Philip Wersén from 1891 to a company building railway rolling stock originally derived from David Ekenberg’s railway stock coachbuilding concern. Vabis merged with Scania in 1910 to create Scania-Vabis, which was involved with limited Swedish car production up to 1920.

Scania originated in Malmö in 1891 as the Maskinfabriks- Aktiebolaget and took over the Svenska-Aktiebolaget Humber & Co of Malmö – Humber being a British agency. Scania started on an experimental design for a Swedish car in 1901 and by the following year had built two such concept cars and a light truck. In 1903 Scania built Sweden’s first ‘production’ car, although this was limited to just five units.

In 1909 Scania built the world’s first truck fitted with proper axles that ran with ball-bearings (Sweden led the world in ball-bearing manufacture). Before 1910 was out Scania would build a series of proper trucks and several more of its cars.

By 1919 Scania-Vabis, based in the town of Södertälje, had produced 830 car chassis units and another 341 car/light commercial chassis types, some of which were sold for export. So the truth is that Scania made ‘Swedish’ cars, of a type that mirrored other early European cars, long before the first true mass-produced, Swedish-designed Saab with its wing-with-wheels car design. Scania eventually went on to become Saab’s partner decades later and Saab cars wore ‘Saab-Scania’ badges until the 1990s.

Another rarity: Gunnar Ljungström’s own sketch illustrates his very first idea for a Saab car before he spoke to Sason. Note the handwritten thoughts on the drawing.

Certain industrial brands became prominent in the affairs of Sweden. The names that became integral to the Saab plot included Bofors, Nohab, Thulin, Nydqvist, Koppaberg and Götaverken, all of which contributed to the heady brew of industrial might as they made links and mergers. AB Svenska Järnvägsverkstäderna (ASJ), with its road, rail and air divisions, was to be a key fulcrum in the creation of the corporate structure that was the final SAAB iteration that we now revere as Saab. It is a rather confusing trail.

Few people beyond the circle of Saab enthusiasts know just how strong was the locomotive, heavy road vehicle and aircraft building history of Sweden between 1900 and 1939, or how it all came together to produce a motor car.

As early as 1921 a company called Svenska Automobil Fabriken (SAF) imported American car engines and components of the ‘Continental’ brand in an early attempt to build a car in Sweden. Twenty-five ‘modified’ cars with local content were made, but few sold. This was the little-known early attempt at a Swedish-made (but not designed) car, but like the first Swedish aircraft, it was not home-grown. General Motors (GM) had a pre-1939 factory in Sweden where Completely Knocked Down (CKD) ‘kits’ of Detroit-designed cars were assembled for the local Swedish market. GM also owned Opel of Germany by this time and half a century later would swallow up Saab.

Before Saab there was Volvo, and before Volvo there was Scania-Vabis, who made a small number of early Swedish cars. This is a rare pre- 1925 Swedish-designed and built Scania-Vabis car.

Also often unseen in the story lies the fact that the Swedish national car dealership company AB Nyköpings Automobilfabrik, later known as ANA and taken over by Saab in 1960, had been established in 1937 to licence-build CKD kits of Chrysler cars for Swedish domestic purchase. This was how large pre-war Chryslers became popular on Swedish roads (but less popular on winter ice and snow).

Prior to its later purchase by Saab, ANA would be the Swedish agents for Ferguson tractors and Standard Ltd’s British cars. ANA had its own assembly workshop and under Saab ownership a plan was drawn up for it to build Saab cars.

Of tangential relevance to Saab was Svenska Aero AB, a company with a corporate structure of confused provenance founded in 1921 with links to Heinkel to circumvent some of the restrictions on German aviation imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. Svenska Aero never really succeded and was absorbed by what was now ASJA in 1932, so bringing it into the Saab story. The later Saab (Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget) should not be confused with this earlier Svenska Aero AB and clarity is required when charting such histories.

Layered within this evolution lay the likes of Enoch Thulin and his company Aero Enoch Thulin Aeroplanfabrik (AETA), which was employing more than 1,000 people building aircraft by the 1920s. Further industrial rationalization would take place by State edict in 1936 under the Swedish Prime Minister, Per Albin Hansson. This threw together all the key players mentioned earlier, and so began the Saab story as an entity.

The Wallenberg family of bankers and investors, which owned a shipping line, transport stocks and the Swedish rights to Rudolf Diesel’s engine design, was also influential within the emerging body. So pivotal were the banking activities of the Wallenbergs that they are considered to have been an essential part of Saab’s first car.

The company was formally registered as Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget on 20 April 1937. Based at Linköping, as a structural subsidiary of the Nohab/Bofors group with a share capital of SKr 4 million, this new body had powerful and well-connected management within its various internal structures. Axel Wenner-Gren was a key investor.

Work soon started on building a factory at Trollhättan and by 1939 Saab was a stand-alone company. Wenner-Gren was the driving force behind it all. There have been allegations about his activities in the 1930s and 1940s, but recent research has clearly confirmed that, although he made errors, he was not aligned to post-1933 German politics as some have claimed.1

The Saab Company that was defined in 1937 had originally been structured to exist alongside the aircraft division of Svenska Järnvägsverkstäderna Aeroplanavdelning (ASJA) and this caused certain internal corporate issues, which were resolved by the creation of AB Förenade Flygverkstäder (AFF) as a new joint entity. By this means ASJA, Svenska Aeroplan AB (Saab) and their respective responsibilities within AFF apparently sidestepped any more confusion as they coalesced by apparent State edict, the power of the Royal Swedish Air Force and under the guidance of several well-chosen committees.

1930s futurism from Sason’s pen as a precursor to the 92’s ellipsoid form.

Another Sason ‘aerodyne’ idea from the mid-1930s with hints of Jaray, Ledwinka and other designers.

That all these companies would end up amalgamated into a greater ‘Saab’ entity creates an interesting framework for the circumstances and influences that moulded the Saab Company, its aircraft and, notably, its first car – the 92.