Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

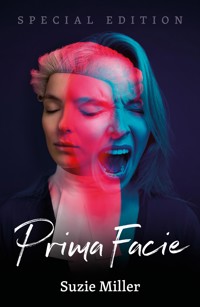

This special edition of the international hit play Prima Facie features the definitive version of the award-winning script, together with colour photos and exclusive additional content, giving you a fascinating behind-the-scenes insight into the making of the production and the issues it explores. In the play, Tessa is a young, brilliant barrister who has worked her way up from working-class origins to the top of her game: defending, cross-examining and winning. But when an unexpected event forces her to confront the patriarchal power of the law – where the burden of proof and morality diverge – she finds herself in a world where emotion and integrity are in conflict with the rules of the game. After acclaimed productions in Australia and winning the Australian Writers' Guild Award for Drama, Prima Facie received its European premiere in a sold-out run at the Harold Pinter Theatre in London's West End in 2022 starring Jodie Comer in her West End debut. It was named Best New Play at both the 2023 Olivier and WhatsOnStage Awards. A filmed version, released in 2022, went on to become the highest-grossing event cinema release ever in the UK. This edition, published alongside Prima Facie's Broadway transfer in 2023, includes contributions from writer Suzie Miller, actor Jodie Comer, director Justin Martin, producer James Bierman and other key members of the creative team, letting you go deeper into the world of the play. There are also essays on the legal context and how the play has become a vehicle for change in attitudes towards the treatment of female victims of sexual assault.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 160

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

IntroductionSuzie Miller

Making Law from Women’s LivesDr Karen O’Connell

Dispelling Sexual Assault MythsHHJ Angela Rafferty

Production History

Creating Prima FacieJustin Martin and Suzie Miller

TestimonialsThe Women: Dani Arlington, Georgia Bird, Miriam Buether, Natasha Chivers, Jodie Comer, Jasmin Hay, Laura Howells, Jane Moriarty, Maddie Sidi and Olivia Ward; The Men: James Bierman and Willie Williams; The Lawyers: Danielle Manson and Kate Parker

Colour Photographs

PRIMA FACIE

AfterwordSuzie Miller

About the Author

Where to Get Support

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

IntroductionSuzie Miller

Prima Facie – A (Latin) legal term meaning: On the face of it.

The idea behind Prima Facie has been playing out in my mind since my law school days, years before I was a playwright. It was there waiting for me to find the courage to write, and for the right social environment to provide a space for it. In light of the #MeToo movement, the play, Prima Facie, was finally able to be realised. Years of practising as a human rights and criminal defence lawyer increased my feminist questioning and interrogation of the legal system, because while I firmly believe that ‘innocent until proven guilty’ is the bedrock of human rights, I always felt that its application in sexual assault cases served to undermine rather than to uphold any real fairness.

I note that the play comes with a trigger warning for those reading it or attending a production of the play. Including details of the sexual assault at the heart of the story allows us to then see how the law reframes a woman’s experience of a horrific crime against the person.

The legal system is shaped by the male experience, its cases decided by generations of male judges and its statutes legislated by generations of male politicians, against a backdrop where women were once categorised as the property of their husbands, brothers and fathers. So sexual assault law does not fit the lived experience of women. Innocence/guilt focuses on whether the (usually) male person reasonably believed consent was or was not provided by the (usually) female person. It has always been the victims, (usually) women, who are ‘on trial’, cross-examined and made to relive their humiliating experience, and then doubted as to their motives for reporting a hideous crime against their person. Yet, significantly, research has shown that women giving evidence in sexual assault cases are just not believed! Even by other women.

To report the crime, endure all the court delays, show up for a prosecution, be cross-examined and publicly written about in the media takes extraordinary courage. It is not a short process either, and ironically indicates an immense faith that the system will be fair. But does the legal system deserve this faith? Or does it silence women further? How can society and therefore the law evolve to reform this area of law?

When Prima Facie was first staged at the Griffin Theatre – Australia’s playwrights’ theatre – a night was sold specially to women in the law. The audience was made up of women judges, QCs, SCs, barristers, solicitors and female politicians from both state and federal parliaments. All of us women. As one of the creatives I sat on stage afterwards. What followed was a long and exciting discussion in which, played out before me, was an authentic intersection between art and social change. Later that week members of the Law Reform Commission also attended a weekday matinee. Later that week we also had a few boys’ schools attend in groups accompanied by teachers and parents. The compassion and curiosity expressed afterwards was a beacon of hope for future generations.

The protagonist of Prima Facie, Tessa Ensler, is a young-blood criminal barrister addicted to the game of law, bursting with social justice and fighting what she believes is the good fight.

She might not have gone to all the right schools, or come from the right socio-economic family background, but she graduated top of her law school year with every major law firm in hot pursuit, all offering her the universe to come work for them. Yet Tessa chooses to fight in the trenches with the most challenging cases, always arguing for the defence, wary of the police and their tricks, and playing fairly and squarely within the rules of the law.

The system of law means you have to believe that the rules are sacrosanct and that your own role is purely a role within a bigger game. What happens when you rise through the ranks, playing by those rules, and you start to realise that some of the rules of the game are actually bendable, breakable? Not always fair?

Tessa is a star player now, but her careful treading within the discretionary parts of this world starts to feel dangerous, and she is caught between her life and her belief system. Suddenly thrust into a situation where she tests the system for herself, Tessa finds that the walls of this trusted watertight structure start to crumble, and there is nothing safe to cling to. Yet for Tessa, seeing the law for what it is – an imperfect human construct, constantly evolving within social changes – frees her to find her voice and call us all to action.

When this play was awarded the prestigious national award, the Griffin Theatre Award in 2018 (and then the prestigious Australian Writers’ Guild Overall Major Award as well as the Australian Writers’ Guild Drama Award and the David Williamson Award in 2020), it proved to me that women’s stories do matter.

The following people have each significantly contributed to the UK edition of Prima Facie; I offer them tremendous gratitude: Her Honour Judge Angela Rafferty; His Honour Judge Murray Shanks; Danielle Manson; Kate Parker, Monica Bhogal and everyone at The Schools Consent Project; Detective Superintendent Clair Kelland; my agents Julia Kreitman, Tanya Tillet and the team at The Agency London; my agent Zilla Turner at HLA Australia; and Matt Applewhite and Sarah Liisa Wilkinson at Nick Hern Books.

I would like to offer my deep personal thanks to producer James Bierman, director Justin Martin and actor Jodie Comer; and to the original team of Lee Lewis and Sheridan Harbridge. My thanks are also due to my wonderful family, Robert, Gabriel and Sasha Beech-Jones, who never stop supporting me and light up excitedly at every new play; and to my beloved mother Elaine Doreen Miller, who I lost just prior to this play’s premiere performance and who was the original inspiration for living a vital, vivid and big life.

My friends are also my family, thank you to my ‘women’s squad’ especially to Rochelle Zurnamer, Karen O’Connell, Sam Mostyn, Nicole Abadee, Hilary Bonney, Jodie Comer, Katie Pollock, Heather Mitchell, Sue Quill, Julia Pincus, Celia Ireland, Greer Simpkin, Poppy Adams, Trish Wadley, Julia

Heath, Lizzie Schultz, Lisa Hunt, Vanessa Bates, Jenny Cooney, Helen Angwin, Danielle Manson, Anna Funder and Anna Cody – who were all involved in discussions around this work. I know there are others and you matter just as much.

And the men: Andrew Post, Rick Goldberg, Caleb Lewis, Justin Martin, Bain Stewart, John Sheedy, Ross Mueller, James Bierman, Dion Slabber and David Jowsey. You all rock.

Lastly, thanks also to the women who share their stories, and those who write women’s stories. In particular I’d like to acknowledge the brilliant V (formerly Eve Ensler), a woman playwright, a human rights advocate, and an inspiration.

April 2022

Making Law from Women’s Lives

Dr Karen O’Connell

This isn’t life. This is law.

To be a woman lawyer is to simultaneously occupy two worlds of meaning. In one of those worlds, law offers a path to professional and public power that was traditionally reserved for men. Yet this sits alongside all the ways that law continues to authorise women’s exclusion from systems of power and redress. Law has failed to adequately regulate, and so enabled many of the harms that women experience: the private, often intimate, harms of domestic violence, marital and date rape, and sexual harassment. For women working in law, are they accessing power or are they part of a system that oppresses and ultimately disempowers them?

The brilliance of Suzie Miller’s play is that she reveals both of these worlds through the one character. Prima Facie introduces us to Tessa Ensler, criminal defence lawyer, who uses words as sensitive, sharp tools for the benefit of her clients and her own career. Hers is initially a world in which law is presumed to be objective and reasonable, a source of power, with no place for emotion or empathy. Then, in the unwanted role of victim and complainant, Tessa is forced into a parallel legal world in which her story of being sexually assaulted is distorted and disbelieved.

Law bestows power and privilege on Tessa, and law takes it away. Miller shows us, in detail, how the usually opaque processes of a criminal trial eviscerate a claim of sexual assault. Both Tessa and we, the audience, know that her story is true. No one tells Tessa that she won’t be believed when she tells the truth in the courtroom. They don’t need to. She knows because she has been on the other side, the side where only ‘legal’ truth matters.

In the first part of Prima Facie, Tessa embodies professional legal power. Law is a game, says Tessa, that works ‘because we all play our roles’. She revels in her legal skills, gleeful as she carefully manipulates a witness (‘tiptoe, tiptoe’), lets him underestimate her (he ‘[t]hinks he is the cat and I am the mouse’) and then pounces. We see how law bestows that power, as Tessa, a working-class girl, becomes one of the legal players that she calls ‘thoroughbreds’, privileged and positioned to change the world. Tessa was told on her first day of law school that one in three students would not make it through the course. She is one of the ones who makes it.

And then, in the second half of the play, Tessa becomes a more brutal statistic: one of the one in three women worldwide who experience sexual and physical violence.

The stories of women sexually assaulted are not easily turned into ‘legal’ truth. The kinds of violence that women are subjected to – mostly by someone they know, mostly in private – are the kinds of violence law has most trouble believing in. In both the UK and the US, the many millions of women who are sexually assaulted rarely receive justice from the criminal justice system. Instead, women’s stories are filtered out of the system as they meet one hurdle after another. On the other side of the criminal trial, where the outcome is supposed to be justice and redress, little remains. In the UK, five out of every six sexual assaults are not reported to police. Of those that are reported, only one in one hundred rapes recorded by police result in a charge – let alone a conviction. Ninety-nine cases, ninety-nine stories out of a hundred, don’t make it through the legal system.

In what sense then, can we say that sexual assault is unlawful?

Law is not separate to life, it is embedded in it – ‘an organic thing… constructed by us, in light of our experiences’. But not all experiences get translated into law, and women’s experiences of sexual assault are not the material of which law is made. Law cannot easily see harm as it manifests in sexual assault or hear experiences of violence against women despite that violence being so ubiquitous. Yet, as Tessa says, it’s not some ‘subtle unreadable thing’ when a woman says no. It is simply not believed.

Our system has grown to care deeply about some genuine problems; for example, that an innocent person should not lose their liberty through a false accusation. This then gets intertwined with damaging stereotypes: the long-held idea, for example, that women were prone to making false accusations against men. That women, jealous and manipulative, would use claims of rape as a tool of power. That women as witnesses were unreliable, because prone to embellishment and exaggeration.

These legal stereotypes are rooted in broader ways of thinking about women’s sexuality. Sexual assault has long tendrils into the past: that women should be subject to the discipline of men; that women who dress immodestly or drink alcohol or had non-marital sex were presumptively available for sex with others; that they should be sexually pure but also sexually available to the man they were lawfully contracted – married – to. It was not an injustice, for example, when women were raped by their husbands. That was not a crime throughout the United States until 1993. Even now, most state jurisdictions in the US provide exceptions, including situations when the victim is asleep, unconscious, or physically helpless. Tessa says:

And there was a time, not so long ago, when courts like this did not ‘see’ non-consensual sex in marriage as rape, did not ‘see’ that battered women fight back in a manner distinct from the way men fight.

Four decades of rape-law reforms around the world have brought about changes designed to make the criminal justice system responsive to sexual assault. In the US and the UK, legislatures removed requirements that a woman use physical force to fight off an assault or provide corroborating evidence. Defence attorneys were prevented from raising evidence of a woman’s prior sexual history to diminish her credibility. Yet when we think back to the yawning gap between the rate of sexual assault and the rate of convictions, it is clear that these reforms have largely failed. Studies from around the world show that women are still routinely believed to be lying when they are sexually assaulted, including by police, the gatekeepers of the system. The highest levels of acceptance are for myths that women invent sexual assault to cover up having an affair, changing their mind about sex, or to seek revenge on men (Sleath and Bull, 2017). And after decades of reform and attempts not to hold women responsible for their own assaults, physical injuries and intensity of struggle are still the strongest indications that a trial will proceed (Fileburn et al, 2016). They remain the threshold for credibility.

As the play proceeds, we see Tessa as witness, ‘ach[ing] for nice-ness’, feeling the emotions that she and her colleagues earlier disdained, and we see why someone – however clever – might be led by a defence lawyer into undermining her own case:

I feel so broken that I want to go with him, just to get it over with,

I want to be reeled in.

All the ordinary things Tessa does – have consensual sex with the colleague, Julian, who later assaults her; drink a lot of wine on a date with him; dance and flirt with him in public – are potentially damning before the law. When Tessa showers after her assault, she is washing off evidence. When, disturbed by Julian’s unwanted contact, she deletes a text he sends her, more evidence is destroyed. And despite her brilliance and power, like so many who have experienced it, she freezes during the assault, and is self-doubting and distressed after. All of these reactions are reasonable and predictable and make sense. They are characteristic reactions to sexual assault. They are also used to undermine Tessa as if they somehow reflect on her credibility. Law does not treat them as normal, expected even, from a woman who has experienced sexual violence.

Fighting to make laws that reflect women’s experiences has been a long, arduous battle. We have centuries of the common law to address, the slow accretion of decisions made in times where women could not vote and could not own property. ‘The law,’ as Tess says, ‘has been shaped by generations and generations of men.’ Yet, the feminist project to reform law so that it reflects the reality of women’s lives has been successful in many ways because it is speaking truth. It is naming things that are material, tangible and painful. Sexual harassment did not exist as a legal harm until the late 1970s when women named it, and feminist lawyers and advocates argued for it to be treated as a form of inequality. There have been valiant attempts to reform criminal law in light of women’s experiences and these have made legislative improvements. And yet, even these successes, when we name something for the first time as a harm or try to remove some damaging assumption about women, can take on a strange flavour. New pieces of legislation still must sit within a distorting system of law. That system has its own culture, its own arcane practices and ways of making meaning. As feminist law reformers, we continually need to be revising laws as they are misread or misapplied by litigators, regulators, policy-makers, judges and juries. But of course, because the laws we write are only animated by human action, and those humans are steeped in the culture we are trying to challenge, the filtering and distorting happens again.

Prima Facie was first performed in the wake of the #MeToo movement and, like that movement, it shows the power of storytelling in the face of injustice. Hearing the rush of stories by women finally and painfully calling out their abusers, men who had been getting away with violence and harassment for years or decades, journalist Amanda Petrusich wrote that she was ‘so hot with anger that there were days when I simply couldn’t catch my breath’. What we do collectively with that anger is the question. Bringing individual complaints before the law, on its own, is not enough. Law reforms, hard won, unravel before our eyes as they are unstitched by the legal system. Tessa, strong, clever and skilled, says that ‘[s]omething has to change’, but what?

Prima Facie itself offers part of the answer. We can change the law as much as we like, but until the experiential material it is made from changes, those laws are easily eroded. The shape that law takes depends on the stories that are heard and the harms that are seen. As #MeToo and other hashtag movements put violence against women centre-stage, some men expressed surprise that harassment was so common an experience, even as it was happening all around them. We have to stop treating every act of violence against women anew, as if there is nothing pervasive or patterned about it. We have to tell our stories everywhere, at once, together.

The #MeToo movement was powerful because when one woman tells her story she can be pilloried for it, or dismissed, but when everyone tells their stories they have a different quality of power, a cultural power. When women collectively tell their stories, and when those stories enter our cultural forms – social media, television, books and theatre – we are changing the culture in which law is embedded, and the material from which it is made.

Prima Facie demonstrates how that can happen. It’s the story of one woman, and the two very different worlds of law she inhabits. It is also the story of the ninety-nine women out of every hundred who are sexually assaulted and who are left out of law. The gap between the two worlds of meaning in Prima Facie