Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

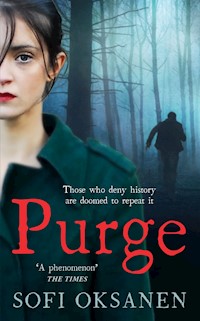

A blowfly. Unusually large, loud, and eager to lay its eggs. It was lying in wait to get into the kitchen, rubbing its wings and feet against the curtain as if preparing to feast. It was after meat, nothing else but meat. Deep in an overgrown Estonian forest, two women, one young, one old, are hiding. Zara, a murderer and a victim of sex-trafficking, is on the run from brutal captors. Aliide, a communist sympathizer and a blood traitor, has endured a life of abuse and the country's brutal Soviet years. Their survival now depends on exposing the one thing that kept them hidden... the truth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 480

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Purge

Sofi Oksanen is a Finnish–Estonian novelist and playwright. Published in thirty-eight countries, Purge is her first novel to appear in English and the first novel to win Finland’s two most prestigious literary awards, the Finlandia and the Runeberg. She lives in Helsinki.

First published in the Finnish language as Puhdistus in 2008 by WSOY.

First published in English translation in the United States of America in 2010 by Black Cat Inc., an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Copyright © Sofi Oksanen, 2008

Translation copyright © Lola Rogers, 2010

The moral right of Sofi Oksanen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Lola Rogers to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Paul-Eerik Rummo’s poems are from the collection Lähettäjän osoite ja toisia runoja 1968–1972 (Sender’s Address and Other Poems, 1968–1972). Translated into English by Lola Rogers from the Finnish translations by Pirkko Huurto, Artipictura, 2005.

The translation of this book was subsidized in part by FILI.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 475 6 eBook ISBN: 978 0 85789 052 8

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

The walls have ears, and the ears have beautiful earrings.

— Paul-Eerik Rummo

Purge

Table of Contents

PART ONE

Free Estonia!

The Fly Always Wins

Zara Searches for a Likely Story

Aliide Prepares a Bath

Zara Admires Some Shiny Stockings and Tastes Some Gin

Every Clink of the Knife Rings Mockingly

In the Wardrobe Is Grandmother’s Suitcase, and in the Suitcase Is Grandmother’s Quilted Coat

Zara Thinks of an Emergency Plan and Aliide Lays Her Traps

Zara Puts on a Red Leather Skirt and Learns Some Manners

Fear Comes Home for the Evening

After the Rocks Come the Songs

Aliide Finds Ingel’s Brooch and Is Horrified

Pasha’s Car Is Getting Closer and Closer

The Photograph That Zara’s Grandmother Gave Her

Thieves’ Tales Only Interest Other Thieves

PART TWO

Free Estonia!

Aliide Eats a Five-Petaled Lilac and Falls in Love

Granny Kreel’s Crows Go Silent

From the Tumult of the Front to the Scent of Syrup

First Let’s Make Some Curtains

Are You Sure, Comrade Aliide?

Aliide Is Going to Need a Cigarette

They Walked in Like They Owned the Place

Aliide’s Bed Begins to Smell of Onions

How Aliide’s Step Became Lighter

The Trials of Aliide Truu

Hans Doesn’t Strike Aliide, Although He Could Have

Aliide Saves a Piece of Ingel’s Wedding Blanket

Even the Movie Man’s Girl Has a Future

Diagnosis

PART THREE

Free Estonia!

The Loneliness of Aliide Truu

A Girl Like a Spring Day

Even a Dog Can’t Chew Through the Chain of Heredity

Aliide Wants to Sleep Through the Night in Peace

Martin Is Proud of His Daughter

Suffering Washes Memory Clean

The Smell of Cod Liver, the Yellow Light of a Lamp

Zara Finds a Spinning Wheel and Sourdough Starter

The Price of Bitter Dreams

Zara Looks Out the Window and Feels the Itch, the Call of the Road

Why Hasn’t Zara Killed Herself?

Zara Looks for a Road with an Unusual Number of Silver Willows at Its End

PART FOUR

Free Estonia!

How Can They See to Fly in the Dark?

Aliide Writes Letters Full of Good News

Aliide Rescues the Sugar Bowl Before It Falls

Hans Tastes Mosquitoes in His Mouth

Zara Finds Some Dead Flowers

Aliide Is Almost Starting to Like the Girl

Why Can’t Hans Love Aliide?

What Did Ingel Tell the Girl About Aliide?

The Passport Kept in the Breast Pocket

The Girl Has Hans’s Chin

Aliide Rubs Her Hands with Goose Fat

Free Estonia!

Free Estonia!

Aliide Kisses Hans and Wipes Blood from the Floor

Free Estonia!

Aliide’s Beautiful Estonian Forest

Free Estonia!

Aliide Packs Up Her Recipe Book and Gets Ready for Bed

PART FIVE

Free Estonia!

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Top Secret

Free Estonia!

PART ONE

There is an answer for everything,if only one knew the question

—Paul-Eerik Rummo

MAY 1949

Free Estonia!

I have to try to write a few words to keep some sense in my head and not let my mind break down. I’ll hide my notebook here under the floor so no one will find it, even if they do find me. This is no life for a man to live. People need people, someone to talk to. I try to do a lot of pushups, take care of my body, but I’m not a man anymore—I’m dead. A man should do the work of the household, but in my house a woman does it. It’s shameful.

Liide’s always trying to get closer to me. Why won’t she leave me alone? She smells like onions.

What’s keeping the English? And what about America? Everything’s balanced on a knife edge—nothing is certain.

Where are my girls, Linda and Ingel? The misery is more than I can bear.

Hans Pekk, son of Eerik, Estonian peasant

1992LÄÄNEMAA, ESTONIA

The Fly Always Wins

Aliide Truu stared at the fly, and the fly stared back. Its eyes bulged and Aliide felt sick to her stomach. A blowfly. Unusually large, loud, and eager to lay its eggs. It was lying in wait to get into the kitchen, rubbing its wings and feet against the curtain as if preparing to feast. It was after meat, nothing else but meat. The jam and all the other canned goods were safe—but that meat. The kitchen door was closed. The fly was waiting. Waiting for Aliide to tire of chasing it around the room, to give up, open the kitchen door. The flyswatter struck the curtain. The curtain fluttered, the lace flowers crumpled, and carnations flashed outside the window, but the fly got away and was strutting on the window frame, safely above Aliide’s head. Self-control! That’s what Aliide needed now, to keep her hand steady.

The fly had woken her up in the morning by walking across her forehead, as carefree as if she were a highway, contemptuously baiting her. She had pushed aside the covers and hurried to close the door to the kitchen, which the fly hadn’t yet thought to slip through. Stupid fly. Stupid and loathsome.

Aliide’s hand clenched the worn, smooth handle of the flyswatter, and she swung it again. Its cracked leather hit the glass, the glass shook, the curtain clips jangled, and the wool string that held up the curtains sagged behind the valance, but the fly escaped again, mocking her. In spite of the fact that Aliide had been trying for more than an an hour to do away with it, the fly had beaten her in every attack, and now it was flying next to the ceiling with a greasy buzz. A disgusting blowfly from the sewer drain. She’d get it yet. She would rest a bit, then do away with it and concentrate on listening to the radio and canning. The raspberries were waiting, and the tomatoes—juicy, ripe tomatoes. The harvest had been exceptionally good this year.

Aliide straightened the drapes. The rainy yard was sniveling gray; the limbs of the birch trees trembled wet, leaves flattened by the rain, blades of grass swaying, with drops of water dripping from their tips. And there was something underneath them. A mound of something. Aliide drew away, behind the shelter of the curtain. She peeked out again, pulled the lace curtain in front of her so that she couldn’t be seen from the yard, and held her breath. Her gaze bypassed the fly specks on the glass and focused on the lawn in front of the birch tree that had been split by lightning.

The mound wasn’t moving and there was nothing familiar about it except its size. Her neighbor Aino had once seen a light above the same birch tree when she was on her way to Aliide’s house, and she hadn’t dared come all the way there, instead returning home to call Aliide and ask if everything was all right, if there had been a UFO in Aliide’s yard. Aliide hadn’t noticed anything unusual, but Aino had been sure that the UFOs were in front of Aliide’s house, and at Meelis’s house, too. Meelis had talked about nothing but UFOs after that. The mound looked like it came from this world, however—it was darkened by rain, it fit into the terrain, it was the size of a person. Maybe some drunk from the village had passed out in her yard. But wouldn’t she have heard if someone were making a racket under her window? Aliide’s ears were still sharp. And she could smell old liquor fumes even through walls. A while ago a bunch of drunks from the next house over had driven out on a tractor with some stolen gasoline, and you couldn’t help but notice the noise. They had driven through her ditch several times and almost taken her fence with them. There was nothing but UFOs, old men, and dim-witted hooligans around here anymore. Her neighbor Aino had come to spend the night at her house numerous times when those boys’ goings-on got too crazy. Aino knew that Aliide wasn’t afraid of them—she’d stand up to them if she had to.

Aliide put the flyswatter that her father had made on the table and crept to the kitchen door, took hold of the latch, but then remembered the fly. It was quiet now. It was waiting for Aliide to open the kitchen door. She went back to the window. The mound was still in the yard, in the same position as before. It looked like a person—she could make out the light hair against the grass. Was it even alive? Aliide’s chest tightened; her heart started to thump in its sack. Should she go out to the yard? Or would that be stupid, rash? Was the mound a thief’s trick? No, no, it couldn’t be. She hadn’t been lured to the window, no one had knocked at the front door. If it weren’t for the fly, she wouldn’t even have noticed it before it was gone. But still. The fly was quiet. She listened. The loud hum of the refrigerator blotted out the silence of the barn that seeped through from the other side of the food pantry. She couldn’t hear the familiar buzz. Maybe the fly had stayed in the other room. Aliide lit the stove, filled the teakettle, and switched on the radio. They were talking about the presidential elections and in a moment would be the more important weather report. Aliide wanted to spend the day inside, but the mound, visible out of the corner of her eye through the kitchen window, disturbed her. It looked the same as it had from the bedroom window, just as much like a person, and it didn’t seem to be going anywhere on its own. Aliide turned off the radio and went back to the window. It was quiet, the way it’s quiet in late summer in a dying Estonian village—a neighbor’s rooster crowed, that was all. The silence had been peculiar that year—expectant, yet at the same time like the aftermath of a storm. There was something similar in the posture of Aliide’s grass, overgrown, sticking to the windowpane. It was wet and mute, placid.

She scratched at her gold tooth, poked at the gap between her teeth with her fingernail—there was something stuck there—and listened, but all she heard was the scrape of her nail against bone, and suddenly she felt it, a shiver up her back. She stopped digging between her teeth and focused on the mound. The specks on the window annoyed her. She wiped at them with a gauze rag, threw the rag in the dishpan, took her coat from the rack and put it on, remembered her handbag on the table and snapped it up, looked around for a good place to hide it, and shoved it in the cupboard with the dishes. On top of the cupboard was a bottle of Finnish deodorant. She hid that away, too, and even put the lid on the sugar bowl, out of which peeped Imperial Leather soap. Only then did she turn the key silently in the lock of the inner door and push it open. She stopped in the entryway, picked up the juniper pitchfork handle that served as a walking stick, but exchanged it for a machine-made city stick, put that down, too, and chose a scythe from among the tools in the entryway. She leaned it against the wall for a moment, smoothed her hair, adjusted a hairpin, tucked her hair neatly behind her ears, took hold of the scythe again, moved the curtain away from the front of the door, turned the latch, and stepped outside.

The mound was lying in the same spot under the birch tree. Aliide moved closer, keeping her eye on the mound but also keeping an eye out for any others. It was a girl. Muddy, ragged, and bedraggled, but a girl nevertheless. A completely unknown girl. A flesh-and-blood person, not some omen of the future, sent from heaven. Her red-lacquered fingernails were in shreds. Her eye makeup had run down her cheeks and her curls were half straightened; there were little blobs of hairspray in them, and a few silver willow leaves stuck to them. Her hair was bleached until it was coarse, and had greasy, dark roots. But under the dirt her skin seemed over-ripe, her cheek white, transparent. Tatters of skin were torn from her dry lower lip, and between them the lip swelled tomato red, unnaturally bright and bloody-looking, making the grime look like a coating, something to be wiped off like the cold, waxy surface of an apple. Purple had collected in the folds of her eyelids, and her black, translucent stockings had runs in them. They didn’t bag at the knees—they were tight-knit, good stockings. Definitely Western. The knit shone in spite of the mud. One shoe had fallen off and lay on the ground. It was a bedroom slipper, worn at the heel, with a flannel lining rubbed to gray pills. The binding along the edge was decorated with dog-eared patent-leather rick-rack and a pair of nickel rivets. Aliide had once had a pair just like them. The rickrack had been pink when it was new, and it looked sweet; the lining was soft and pink like the side of a new pig. It was a Soviet slipper. The dress? Western. The tricot was too good to come from over on the other side. You couldn’t get them anywhere but in the West. The last time her daughter Talvi had come back from Finland she had had one like it, with a broad belt. Talvi had said that it was in style, and she certainly knew about fashion. Aino got a similar one from the church care package, although it was no use to her—but after all, it was free. The Finns had enough clothes that they even threw new ones away into the collection bin. The package had also contained a Windbreaker and some T-shirts. Soon it would be time to pick up another one. But this girl’s dress was really too handsome to be from a care package. And she wasn’t from around here.

There was a flashlight next to her head. And a muddy map.

Her mouth was open, and as she leaned closer, Aliide could see her teeth. They were too white. The gaps between her white teeth formed a line of gray spots.

Her eyes twitched under their lids.

Aliide poked the girl with the end of the scythe, but there was no movement. Yoo-hoos didn’t get any flicker from the girl’s eyelids, neither did pinching. Aliide fetched some rainwater from the foot washbasin and sprinkled her with it. The girl curled up in a fetal position and covered her head with her hands. Her mouth opened in a yell, but only a whisper came out:

“No. No water. No more.”

Then her eyes blinked open and she sat bolt upright. Aliide moved away, just to be safe. The girl’s mouth was still open. She stared in Aliide’s direction, but her hysterical gaze didn’t seem to register her. It didn’t register anything. Aliide kept assuring her that everything was all right, in the soothing voice you use with restless animals. There was no comprehension in the girl’s eyes, but there was something familiar about her gaping mouth. The girl herself wasn’t familiar, but the way she behaved was, the way her expressions quivered under her waxlike skin, not reaching the surface, and the way her body was wary in spite of her vacant demeanor. She needed a doctor, that was clear. Aliide didn’t want to attempt to take care of her herself—a stranger, in such questionable circumstances—so she suggested they call a doctor.

“No!”

Her voice sounded certain, although her gaze was still unfocused. A pause followed the shriek, and a string of words ran together immediately after, saying that she hadn’t done anything, that there was no need to call anyone on her account. The words jostled one another, beginnings of words were tangled up with endings, and the accent was Russian.

The girl was Russian. An Estonian-speaking Russian.

Aliide stepped farther back.

She ought to get a new dog. Or two.

The freshly sharpened blade of the scythe shone, although the rain-dampened light was gray.

Sweat rose on Aliide’s upper lip.

The girl’s eyes started to focus, first on the ground, on one leaf of plantain weed, then another, slowly moving farther away to the rocks at the edge of the flower bed, to the pump, and the basin under the pump. Then her gaze moved back to her own lap, to her hands, stopped there, then slid up to the butt end of Aliide’s scythe, but didn’t go any higher, instead returning to her hands, the scratch marks on the backs of her hands, her shredded fingernails. She seemed to be examining her own limbs, perhaps counting them, arm and wrist and hand, all the fingers in place, then going through the same thing with the other hand, then her slipperless toes, her foot, ankle, lower leg, knee, thigh. Her gaze didn’t reach to her hips—it shifted suddenly to the other foot and slipper. She reached her hand toward the slipper, slowly picked it up, and put it on her foot. The slipper squooshed. She pulled her foot toward her with the slipper on it and slowly felt her ankle, not like a person who suspects that her ankle is sprained or broken, but like someone who can’t remember what shape her ankle normally is, or like a blind person feeling an unknown thing. She finally managed to get up, but still didn’t look Aliide in the face. When she got firmly to her feet, she touched her hair and brushed it toward her face, although it was wet and slimy-looking, pulling it in front of her like tattered curtains in an abandoned house where there was no life to be concealed.

Aliide tightened her grip on the scythe. Maybe the girl was crazy. Maybe she had escaped from somewhere. You never know. Maybe she was just confused, maybe something had happened that caused her to be like that. Or maybe it was that she was in fact a decoy for a Russian criminal gang.

The girl sat herself up on the bench under the birch tree. The wind washed the branches against her, but she didn’t try to avoid them, even though flapping leaves slapped against her face.

“Move away from those branches.”

Surprise flickered across the girl’s cheeks. Surprise mixed with something else—she looked like she was remembering something. That you can get out of the way of leaves that are lashing at you? Aliide squinted. Crazy.

The girl slumped away from the branches. Her fingers clung to the edge of the bench like she was trying to prevent herself from falling. There was a whetstone lying next to her hand. Hopefully she wasn’t someone who would anger easily and start throwing rocks and whetstones. Maybe Aliide shouldn’t make her nervous. She should be careful.

“Now where exactly did you come from?”

The girl opened her mouth several times before any speech came out—groping sentences about Tallinn and a car. The words ran together like they had before, connecting to one another in the wrong places, linking up prematurely, and they started to tickle strangely in Aliide’s ear. It wasn’t the girl’s speech or her Russian accent; it was something else—there was something strange about her Estonian. Although the girl, with her dirty young skin, belonged to today, her sentences were awkward; they came from a world of brittle paper, moldy old albums emptied of pictures. Aliide removed a hairpin from her head and shoved it into her ear canal, turned it, took it out, and put it back in her hair. The tickle remained. She had a flashing thought: The girl wasn’t from anywhere around here—maybe not from Estonia at all. But what foreigner would know this kind of provincial language? The village priest was a Finn who spoke Estonian. He had studied the language when he came here to work, and he knew it well, wrote all his sermons and eulogies in Estonian, and no one even bothered to complain about the shortage of Estonian priests anymore. But this girl’s Estonian had a different flavor, something older, yellow and moth-eaten. There was a strange smell of death in it.

From the slow sentences it became clear that the girl was on her way to Tallinn in a car with someone and had got into a fight with this someone, and the someone had hit her, and she had run away.

“Who were you with?” Aliide finally asked.

The girl’s lips trembled a moment before she mumbled that she had been traveling with her husband.

Her husband? So she was married? Or was she a decoy for thieves? For a criminal decoy, she was rather incoherent. Or was that the idea, to arouse sympathy? That no one would close their door on a poor girl in the state she was in? Were the thieves after Aliide’s belongings or something in the woods? They’d been taking everyone’s wood and sending it to the West, and Aliide’s land restitution case wasn’t even close to completion, although there shouldn’t have been any problem with it. Old Mihkel in the village had ended up in court when he shot some men who had come to cut trees on his land. He hadn’t gotten in much trouble for it—there had been some surreptitious coughing and the court had taken the hint. Mihkel’s process to get his land back had been only half completed when the Finnish logging machinery suddenly appeared and started to cut down his trees. The police hadn’t meddled in the matter—after all, how could they protect one man’s woods all night, especially if he didn’t even officially own them? So the woods just disappeared, and in the end Mihkel shot a couple of the thieves. Anything was possible in this country right now—but nobody was going to cut trees on Mihkel’s land without permission anymore.

The village dogs started to bark, the girl startled and tried to peek through the chain-link fence into the road, but she didn’t look toward the woods.

“Who were you with?” Aliide repeated.

The girl licked her lips, peered at Aliide and at the fence, and started rolling up her sleeves. Her movements were clumsy—but considering her condition and her story, graceful enough. Her mottled arms were revealed and she stretched them toward Aliide as if in proof of what she was saying, at the same time turning her head toward the fence to hide it.

Aliide shuddered. The girl was definitely trying to elicit sympathy—maybe she wanted inside the house to see if there was anything to be stolen. They were real bruises, though. Nevertheless, Aliide said:

“Those look old. They look like old bruises.”

The freshness of the marks and their bloodiness brought more sweat to Aliide’s upper lip. The bruises were covered up again, and there was silence. That’s the way it always went. Maybe the girl noticed Aliide’s distress, because she pulled the fabric over the bruises with a sudden, jerky movement, as if she hadn’t realized until that moment the shame in revealing them, and she said anxiously, looking toward the fence, that it had been dark and she hadn’t known where she was, she just ran and ran. The broken sentences ended with her assuring Aliide that she was already leaving. She wouldn’t stay there to trouble her.

“Wait right there,” Aliide said. “I’ll bring some valerian and water.” She went toward the house and glanced at the girl again from the doorway. She was perched motionless on the bench. It was clear she was afraid. You could smell the fear from a long way off. Aliide noticed herself starting to breathe through her mouth. If the girl was a decoy, she was afraid of the people who sent her here. Maybe Aliide should be, too—maybe she should take the girl’s trembling hands as a sign that she should lock the door and stay inside, keep the girl out, come what may, just so she would go away and leave an old person in peace. Just so she wouldn’t stay here spreading the repulsive, familiar smell of fear. Maybe there was some gang about, going through all the houses. Maybe she should call and ask. Or had the girl come to her house specifically? Had someone heard that Talvi was coming from Finland to visit? But that wasn’t a big deal as it used to be.

In the kitchen, Aliide ladled water into a mug and mixed in a few drops of valerian. She could see the girl from the window—she hadn’t moved at all. Aliide took some valerian herself, and a spoonful of heart medicine, although it wasn’t mealtime, then went back outside and offered the mug. The girl took it, sniffed at it carefully, set it down on the ground, pushed it over, and peered at the liquid as it sank into the earth. Aliide felt annoyed. Was water not good enough?

The girl assured her to the contrary, but she wanted to know what Aliide had put in it.

“Just valerian.”

The girl didn’t say anything.

“Do I have any reason to lie to you?”

The girl glanced at Aliide. There was something canny in her expression. It troubled Aliide, but she fetched another mug of water and the valerian bottle from the kitchen, and gave them to the girl, who was satisfied once she had smelled it that it was just water, seemed to recognize the valerian, and poured a few drops into the mug. Aliide was annoyed. Was the girl teasing her? Maybe she was just plain crazy. Escaped from the hospital. Aliide remembered a woman who got out of Koluvere, got an evening gown from the free box, and went running through the village spitting on strangers as they passed by.

“So the water’s all right?”

The girl gulped too eagerly, and liquid streamed down her chin.

“A moment ago I tried to rouse you and you yelled, ‘No water.’”

The girl clearly didn’t remember, but her earlier sobs still echoed in Aliide’s head, reverberating from one side of her skull to the other, spinning back and forth, beckoning to something much older. When a person’s head has been pushed under the water enough times, the sound they let out is surprisingly consistent. That familiar sound was in the girl’s voice. A sputtering, without end, hopeless. Aliide’s hand fought with her. She was aching to slap the girl. Be quiet. Beat it. Get lost. But maybe she was wrong. Maybe the girl had just gone swimming once and nearly drowned—maybe that’s why she was afraid of water. Maybe Aliide was letting her imagination run away with her, making connections where there weren’t any. Maybe the girl’s yellowed, time-eaten language had got Aliide thinking of her own.

“Hungry? Are you hungry?”

The girl looked like she hadn’t understood the question or like she had never been asked such a thing.

“Wait here,” Aliide commanded, and went inside again, closing the door behind her. She soon returned with black bread and a dish of butter. She had hesitated about the butter for a moment but had decided to bring it with her. She shouldn’t be so stingy that she couldn’t spare a little dab for the girl. A very good decoy, indeed, to take in someone like Aliide, who had seen it all, and so easily. The compulsive ache in Aliide’s hand spread to her shoulder. She held on to the butter plate too tightly, to restrain her desire to strike.

The mud-stained map was no longer on the grass. The girl must have put it in her pocket.

The first slice of bread disappeared into the girl’s mouth whole. It wasn’t until the third that she had the patience to put butter on it, and even then she did it in a panic, shoving a heap of it into the middle of the slice, then folding it in half and pressing it together to spread the butter in between, and taking a bite. A crow cawed on the gate, dogs barked in the village, but the girl was so focused on the bread that the sounds didn’t make her flinch like they had before. Aliide’s galoshes were shining like good polished boots. The dew was rising over her feet from the damp grass.

“Well, what now? What about your husband? Is he after you?” Aliide asked, watching her closely as she ate. It was genuine hunger. But that fear. Was it only her husband she was afraid of?

“He is after me. My husband is.”

“Why don’t you call your mother, have her come and get you? Or let her know where you are?”

The girl shook her head.

“Well, call some friend, then. Or some other family member.”

She shook her head again, more violently than before.

“Then call someone who won’t tell your husband where you are.”

More shakes of the head. Her dirty hair flew away from her face. She combed it back in place and looked more clear-headed than crazy, in spite of her incessant cringing. There was no glimmer of insanity in her eyes, although she peered obliquely from under her brow all the time.

“I can’t take you anywhere. Even if I had a car, there’s no gas here. There’s a bus from the village once a day, but it’s not reliable.”

The girl assured her she would be leaving soon.

“Where will you go? Back to your husband?”

“No!”

“Then where?”

The girl poked her slipper at the stones in the flower bed in front of the bench. Her chin was nearly on her breast.

“Zara.”

Aliide was taken aback. It was an introduction.

“Aliide Truu.”

The girl stopped poking at the stone. She had grabbed hold of the edge of the bench after she’d eaten, and now she loosened her grip. Her head rose a little.

“Nice to meet you.”

1992LÄÄNEMAA, ESTONIA

Zara Searches for a Likely Story

Aliide. Aliide Truu. Zara’s hands let go of the bench. Aliide Truu was alive and standing in front of her. Aliide Truu lived in this house. The situation felt as strange as the language in Zara’s mouth. She dimly remembered how she had managed to find the right road and the silver willows on the road, but she couldn’t remember if she had realized that she had found it, or whether she had stood in front of the door during the night, not knowing what to do, or decided that she would wait until the morning, so she wouldn’t frighten anyone by coming as a stranger during the night, or whether she had tried to go into the stable to sleep, or looked in the kitchen window, not daring to knock on the door, or if she had even thought of knocking on the door, or thought of anything. When she tried to remember, she felt a stabbing in her head, so she concentrated on the present moment. She didn’t have any plan ready for how to behave when she got here, much less for when she met the woman she was looking for here in the yard, Aliide Truu. She hadn’t had time to think that far. Now she just had to try to make her way forward, to calm her feeling of panic, although it was waiting to break out and grab her at any moment—she had to stop thinking about Pasha and Lavrenti, she had to dare to be in the present moment, meeting Aliide Truu. She had to pull herself together. She had to be brave. To remember how to behave with other people, to think up an attitude toward the woman standing in front of her. The woman’s face was made of small wrinkles and delicate bones, but there was no expression in it. Her earlobes were elongated, and stones embedded in gold hung from them on hooks. They reflected red. Her irises seemed gray or blue gray, her eyes watery, but Zara hardly dared to look higher than her nose. Aliide was smaller than she had expected, downright skinny. The aroma of garlic wafted from her on the wind.

There wasn’t much time. Pasha and Lavrenti would find her, she had no doubt of that. But here was Aliide Truu, and here was the house. Would the woman agree to help? Zara had to make her understand the situation quickly, but she didn’t know what to say. Her head rang empty, although the bread had cleared her thoughts. Mascara tickled her eyes, her stockings were wrecked, she smelled. It had been stupid to show her the bruises—now she thought that Zara was the kind of girl who brings misfortune on herself or asks to be beaten. A girl who had done something wrong. And what if the old woman was like the babushka that Katia had told her about, or like Oksanka, who did work for men like Pasha, sending girls to the city for men like him. There was no way of knowing. Somewhere in the back of her mind there was mocking laughter, and it was Pasha’s voice, and it reminded her that a girl as stupid as she was would never make it on her own. A stupid girl like her was only fit to have the stuttering, slovenliness, smelliness beat out of her—a girl that stupid deserved to be drowned in the sink, because she was hopelessly stupid and hopelessly ugly.

It was awkward the way Aliide Truu kept looking at her, leaning on her scythe, chattering about the closing of the kolkhoz commune, as if Zara were an old acquaintance who had stopped by to chat about nothing in particular.

“There aren’t a terrible lot of visitors around here anymore,” Aliide said, and started to tally up the houses whose young people had moved away. “Everybody left Kokka to build houses for the Finns, and all the children from Roosna left to start businesses in Tallinn. The Voorels’ boy got into politics and disappeared somewhere in Tallinn. Someone should call them and tell them that they passed a law that says you can’t just up and leave the countryside. How are we supposed to even get a roof fixed around here, if there aren’t any workmen? And is it any wonder that the men don’t stay, when there aren’t any women? And there aren’t any women, because there are no businessmen. And when all the women want is businessmen and foreigners, who’s going to want a working man? The West Kaluri fishing commune sent its own variety show to perform in Finland, in Hanko, their sister city, and it was a successful trip, the Finns were lining up for tickets. Then, when the group came home, the director gave an invitation to all the young men and pretty girls to come dance the cancan for the Finns—right in the newspaper. The cancan!”

Zara nodded—she strongly agreed—as she scratched the polish off of her fingernails. Yes, everyone was just running after dollars and Finnish markka, and yes, there used to be work for everyone, and yes, everyone was a thief nowadays, pretending to be a businessman. Zara started to feel cold, and the stiffness spread to her cheeks and tongue, which made her already-slow and hesitant speech still more difficult. Her damp clothes made her shiver. She didn’t dare to look directly at Aliide, she just glanced in her direction. What was she driving at? They chatted as if the situation were an utterly normal one. Her head wasn’t spinning quite so badly now. Zara pushed her hair behind her ears, as if to hear better, and lifted her chin. Her skin felt sticky, her voice felt stiff, her nose trembled, her armpits and groin were filthy, but she managed to laugh lightly nevertheless. She tried to reproduce the voice she had sometimes used a long time ago when she ran into an old acquaintance on the street or in a shop. A voice that felt far away and strange, completely unfitted to the body that it came from. It reminded her of a world she didn’t belong to, a home she could never return to.

Aliide swung the scythe northward and moved on to roof-tile thieves. You had to be on the lookout day and night just to keep a roof over your head. The Moisios had even had their stairs stolen, and the rails from the railroad tracks—the only material available was wood, because everything else had been stolen. And the rise in prices! Kersti Lillemäki said that prices like this were a sign of the end of the world.

And then, in the middle of this chitchat, came a surprising question:

“What about you? Do you have a job? What line of work are those clothes for?”

Zara panicked again. She realized that she needed an explanation for her ragged appearance, but what could it be? Why hadn’t she already thought of it? Her thoughts dashed away from her like long-legged animals, impossible to catch. Every species of lie deserted her, emptied her head, emptied her eyes and ears. She desperately wrestled a few words into a sentence, said she had been a waitress, and as she looked at her legs she remembered her Western clothes and added that she had been working in Canada. Aliide raised her eyebrows.

“So far away. Did you earn good money?”

Zara nodded, trying to think of something more to say. When she nodded, her teeth started to chatter and closed like a trap. Her mouth was full of phlegm and dirty teeth, but not one sensible word. She wished the woman would stop questioning her. But Aliide wanted to know what Zara was doing here if she had such a good job in Canada.

Zara took a breath, said she had come with her husband on vacation to Tallinn. The sentence came out well. It followed the same rhythm as Aliide’s speech. She was already starting to get the hang of it. But what about her story? What would be an appropriate story for her? The beginning of the story she had just made up was struggling to get away, and Zara’s mind lunged after it and grabbed it by the paws. Stay here. Help me. Bit by bit, word by word, give me a story. A good story. Give me the kind of story that will make her let me stay here and not call someone to come and take me away.

“What about your husband? Was he in Canada, too?”

“Yes.”

“And the two of you are on vacation?”

“That’s right.”

“Where did you plan to go from here?”

Zara filled her lungs with air and succeeded in saying in one breath that she didn’t know. And that a lack of funds had made matters a little difficult. She shouldn’t have said that. Now, of course, Aliide would think she was after her wallet. The trap sprang open. Her story escaped. The good beginning slipped away. Now Aliide would never let her inside, and nothing would ever come of any of it. Zara tried to think of something, but all her thoughts were dashing away as soon as they were born. She had to tell her something—if not her story, then something else—anything. She searched for something to say about the molehills that stretched in a row from the end of the house, the tar-paper roofs of the bees’ nests peeking between apple trees heavy with fruit, the grindstone standing on the other side of the gate, the plantain weed under her feet. She searched for something to say like a hungry animal searching for prey, but everything slipped loose from the dull stubs of her teeth. Soon Aliide would notice her panic, and when that happened, Aliide would think, There’s something not right about this girl, and then it would all be over, everything ruined, Zara just as stupid as Pasha said she was, always ruining everything, a stupid girl, a hopeless idiot.

Zara glanced at Aliide, although she no longer had even her hair as a curtain between them. Aliide gave her body a once-over. Zara’s skin was filthy with mud and dirt. What she needed was some soap.

1992LÄÄNEMAA, ESTONIA

Aliide Prepares a Bath

Aliide told the girl to sit down on a wobbly kitchen chair. She obeyed. Her gaze wandered and came to rest on the tin of salt left between the windowpanes over the winter, as if it were a great wonder to her.

“The salt absorbs moisture. So the windows don’t fog up in the cold.”

Aliide spoke slowly. She wasn’t sure if the girl’s mind was working at full power. Although she had recovered a little outside, she’d put her slipper in the door so warily, as though the floor were made of ice that wasn’t sure to hold her, and when she made it to the chair she was more withdrawn and huddled than she’d been in the yard. Aliide’s instincts told her not to let the girl inside, but she seemed to be in such a bad state that there was no other choice. The girl was startled again when she leaned back and the kitchen curtain brushed against her arm. The flinch made her lean forward again, and the chair swayed, and she had to fumble to keep her balance. Her slipper hissed against the floor. When the chair steadied, her foot stopped swinging and she grabbed the edge of the seat. She tucked her feet under her, then wrapped her arms around her sides and drooping shoulders.

“Lemme get you something dry to put on.”

Aliide left the door to the front room open and dug through the few housedresses and slips in the wardrobe. The girl didn’t move, she just perched on the chair chewing her lower lip. Her expression had sunk back into what it had been in the beginning. Aliide felt revulsion well up in her. The girl would leave soon, but not before they figured out where to send her and gave her a little medicine. They weren’t going to sit there waiting for another visitor—the girl’s husband or whoever it was that was after her. If she wasn’t thieves’ bait, then whose bait was she? The boys in the village? Would they do something that elaborate? And why? Just to torment her, or was there something else behind it? But the village boys definitely wouldn’t use a Russian girl—never.

When Aliide went back into the kitchen, the girl heaved her shoulders and head and turned toward her. Her eyes looked away. She wouldn’t accept the clothes, said she only wanted some pants.

“Pants? I don’t have any except for sweatpants, and they’d need to be washed, for sure.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“I wear them to work outside.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“All right!”

Aliide went to look for the Marat pants hanging from the coatrack in the entryway, at the same time straightening her own underwear. She was wearing two pairs, as usual, as she had every day since that night at town hall. She had also tried men’s breeches sometimes. They had briefly made her feel safer. More protected. But women didn’t wear long pants back then. Later on, women appeared in pants even in the village, but by that time she was so used to two pairs of underwear that she didn’t hanker after long pants. But why would a girl in a Western dress want a pair of Marat-brand sweatpants?

“These were made after Marat got those Japanese knitting machines,” Aliide said, and laughed, coming back into the kitchen. After a tiny pause, the girl let out a giggle. It was a brief giggle, and she swallowed it immediately, the way people do when they don’t get the joke but they don’t dare or don’t want to admit it, so they laugh along. Or maybe it wasn’t a joke to her. Maybe she was so young that she didn’t remember what Marat knits were like before the new machines. Or maybe Aliide was right in guessing that the girl wasn’t Estonian at all.

“We’ll wash and mend your dress later.”

“No!”

“Why not? It’s an expensive dress.”

The girl snatched the pants from Aliide, peeled off her stockings, pulled on the Marats, tore off her dress, slipped on Aliide’s housedress in its place, and before Aliide could stop her, threw her dress and stockings into the stove. The map fluttered onto the rug. The girl snapped it up and threw it into the fire with the clothes.

“Zara, there’s nothing to worry about.”

The girl stood in front of the stove as if to shelter the burning clothes. The housedress was buttoned crooked.

“How about a bath? I’ll put some water on to warm,” Aliide said. “There’s nothing to worry about.”

Aliide came toward the stove slowly. The girl didn’t move. Her panicked eyes flickered. Aliide poured the kettle full, took hold of the girl’s hand and led her to the chair, set a hot glass of tea on the table in front of her, and went back to the stove. The girl turned to watch her movements.

“Let them burn,” Aliide said.

The girls eyebrow was no longer twitching. She started to scratch at her nail polish, concentrating on each finger one by one. Did it calm her down? Aliide fetched a bowl of tomatoes from the pantry and put it on the table, glanced at the loaded mousetrap beside the pile of cucumbers, and inspected her recipe book and the jars of mixed vegetables she’d left on the counter to cool.

“I’m about to can tomatoes. And the raspberries from yesterday. Shall we see what’s on the radio?”

The girl grabbed a magazine and rustled it loudly against the oilcloth. The glass of tea spilled over the magazine, the girl was frightened, and she jumped away from the table, stared at the glass and at Aliide in turn, and started to rapidly apologize for the mess, but messed up the words, then nervously tried to clean it up, looking for a cloth, then wiping the floor, the glass, and the legs of the table, and patting the already-ragged kitchen mat dry.

“It’s all right.”

The girl’s panic didn’t subside, and Aliide had to calm her down again—it’s all right, there’s nothing to worry about, just calm down, it’s just a glass of tea, let it be, why don’t you fetch the washtub from the back room, there should be enough warm water now. The girl dashed off quickly, still looking apologetic, brought the zinc tub clattering into the kitchen, and rushed between the stove and the tub carrying hot water and then cold water to add to it. She kept her gaze toward the floor; her cheeks were red, her movements conciliatory and smooth. Aliide watched her at work. An unusually well-trained girl. Good training like that took a hefty dose of fear. Aliide felt sorry for her, and as she handed her a linen towel decorated with Lihula patterns, she held the girl’s hands in her own for a moment. The girl flinched again; her fingers curled up and she pulled her hand away, but Aliide wouldn’t let her go. She felt like petting the girl’s hair, but she seemed too averse to being touched, so Aliide just repeated that there was nothing to worry about. She should just calmly get in the bath, then put on some dry clothes, and have something to drink. Maybe a glass of cold, strong sugar water. How about if she mixed some up right now?

The girl’s fingers straightened. Her fright started to ease, her body settled. Aliide carefully loosened the girl’s hand from her own and mixed up some soothing sugar water. The girl drank it, the glass trembled, a swirling storm of sugar crystals. Aliide encouraged her to get into the bath, but she wouldn’t budge until Aliide agreed to wait in the front room. She left the door ajar and heard the water splashing, and now and then a small, childlike sigh.

The girl didn’t know how to read Estonian. She could speak but not read. That’s why she had flipped through the magazine so nervously and knocked over her glass—maybe on purpose, to keep Aliide from seeing that she was illiterate.

Aliide peeked through the crack in the door. The girl’s bruised body sprawled in the tub. The tangled hair at her temples stuck out like an extra, listening ear.

1991VLADIVOSTOK, RUSSIAN FEDERATION

Zara Admires Some Shiny Stockings and Tastes Some Gin

One day, a black Volga pulled up in front of Zara’s house. Zara was standing on the steps when the car stopped, the door of the Volga opened, and a foot clothed in a shiny stocking emerged and touched the ground. At first Zara was afraid—why was there a black Volga in front of their house?—but she forgot her fright when the sun hit Oksanka’s lower leg. The babushkas got quiet on the bench beside the house and stared at the shining metal of the car and the glistening leg. Zara had never seen anything like it; it was the color of skin; it didn’t look anything like a stocking. Maybe it wasn’t a stocking at all. But the light gleamed on the surface of the leg in such a way that there had to be something there—it wasn’t just a naked leg. It looked as if it had a halo, like the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, gilded with light at the edges. The leg ended in an ankle and a high-heeled shoe—and what a shoe! The heel was narrow in the middle, like a slender hourglass. She’d seen Madame de Pompadour wearing shoes like that in old art-history books, but the shoe that emerged from the car was taller and more delicate, with a slightly tapered toe. When the shoe was set down on the dusty road and the heel landed on a stone, she heard a tearing sound all the way from the porch. Then the rest of the woman got out of the car. Oksanka.

Two men in black leather coats with thick gold chains around their necks got out of the front of the car. They didn’t say anything, just stood beside the car staring at Oksanka. And there was plenty to stare at. She was beautiful. Zara hadn’t seen her old friend in a long time, not since she’d moved to Moscow to go to the university. She had received a few cards from her and then a letter that said that she was going to work in Germany. After that she hadn’t heard from her at all until this moment. The transformation was amazing. Oksanka’s lips glimmered like someone’s in a Western magazine, and she had on a light brown fox stole, not the color of fox but more like coffee and milk—or were there foxes that color?

Oksanka came toward the front door, and when she saw Zara she stopped and waved. Actually it looked more like she was scraping at the air with her red fingernails. Her fingers were slightly curled, as if she were ready to scratch. The babushkas turned to look at Zara. One of them pulled her scarf closer around her head. Another pulled her walking stick between her legs. A third took hold of her walking stick in both hands.

The horn of the Volga tooted.

Oksanka approached Zara. She came up the stairs smiling, the sun played against her clean, white teeth, and she reached out her taloned hands in an embrace. The fox stole touched Zara’s cheek. Its glass eyes looked at her, and she looked back. The look seemed familiar. She thought for a moment, then realized that her grandmother’s eyes sometimes looked like that.

“I’ve missed you so much,” Oksanka whispered. A sticky shine spilled over her lips and it looked like it was difficult to part them, as if she had to tear her mouth unglued whenever she opened it.

The wind fluttered a curl of Oksanka’s hair against her lips, she flicked it away, and the curl brushed her cheek and left a red streak there. There were similar streaks on her neck. It looked like she’d been hit with a switch. As Oksanka squeezed her hand, Zara felt her fingernails, little stabs into her skin.

“You need to go to the salon, honey,” Oksanka said with a laugh, rumpling her hair. “A new color and a decent style!”

Zara didn’t say anything.

“Oh yeah—I remember what the hairdressers are like here. Maybe it would be best if you didn’t let them touch your hair.” She laughed again. “Let’s have some tea.”

Zara took Oksanka inside. The communal kitchen went quiet as they walked through. The floor creaked, women came to the door to watch them. Zara’s down-at-the-heel slippers squeaked as she walked over the sand and sunflower seed shells. The women’s eyes made her back tingle.

She let Oksanka into the apartment and closed the door behind her. In the dim room, Oksanka shone like a shooting star. Her earrings flashed like cat’s eyes. Zara pulled the sleeves of her housecoat over the reddened backs of her hands.

Grandmother’s eyes didn’t move. She sat in her usual place, staring out the window. Her head looked black against the incoming light. Grandmother never left that one chair, she just looked out the window without speaking, day and night. Everyone had always been a little afraid of Grandmother, even Zara’s father, although he was drunk all the time. Then he had faded and died and Zara’s mother had moved with Zara back to Grandmother’s house. Grandmother had never liked him and always called him tibla—Russian trash. But Oksanka was used to Grandmother and clattered over to greet her immediately, took her hand, and chatted pleasantly with her. Grandmother may have even laughed. When Zara began to clear the table, Oksanka dug through her purse and found a chocolate bar that sparkled as much as she did and gave it to Grandmother. Zara put the heating coil in the kettle. Oksanka came up beside her and handed her a plastic bag.

“There are all kinds of little things in here.”

Zara hesitated. The bag looked heavy.

“Just take it. No, wait a minute,” Oksanka pulled a bottle from the bag. “This is gin. Has your grandmother ever had anything like gin? Maybe it would be a new experience for her.”

She grabbed some schnapps glasses from the shelf, filled them, and took a glass to Grandmother. Grandmother sniffed at the drink, grinned, laughed, and dashed the contents into her mouth. Zara followed suit. An acrid burning spread through her throat.

“Gin is what they make gin and tonics from. We make quite a lot of them for our customers.” Then she pretended to bustle about with a tray and put drinks on the table, and said in English, “Vould you like to have something else, sir? Another gin tonic, sir? Noch einen