Queer Square Mile E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

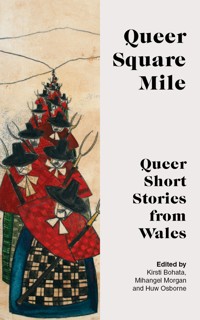

QUEER SQUARE MILE: Queer Short Stories from Wales Edited by Kirsti Bohata, Mihangel Morgan and Huw Osborne This ground-breaking volume makes visible a long and diverse tradition of queer writing from Wales. Spanning genres from ghost stories and science fiction to industrial literature and surrealist modernism, these are stories of love, loss and transformation. In these stories gender refuses to be fixed: a dashing travelling companion is not quite who he seems in the intimate darkness of a mail coach, a girl on the cusp of adulthood gamely takes her father's place as head of the house, and an actor and patron are caught up in dangerous game-playing. In the more fantastical tales there are talking rats, flirtations with fascism, and escape from a post-virus 'utopia'. These are stories of sexual awakening, coming out and redefining one's place in the world. Release and a certain heady license may be found in the distant cities of Europe or north Africa, but the stories are for the most part located in familiar Welsh settings – a schoolroom, a provincial town, a mining village, a tourist resort, a sacred island. The intensity of desire, whether overt, playful, or coded, makes this a rich and often surprising collection that reimagines what being queer and Welsh has meant in different times and places. The first anthology of its kind in Wales, which finally sheds light on a largely hidden queer cultural history with the careful selection of over 40 short stories (1837-2018). New translations of Kate Roberts, Mihangel Morgan, Jane Edwards, Pennar Davies and Dylan Huw make available their compelling stories for the first time to a non-Welsh speaking readership. Previously unpublished works by writers such as Margiad Evans and Ken Etheridge appear alongside better known favourites.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 983

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

About the Editors

Title Page

Introduction

LOVE, LOSS, AND THE ART OF FAILURE

The Treasure – Kate Roberts

The Kiss – Glyn Jones

The Fraying of the Thread – Kathleen Freeman

Christmas – Kate Roberts

The Mistake – Kathleen Freeman

A Modest Adornment – Margiad Evans

Red Earth, Cyrenaica – Stevie Davies

Knowledge – Glyn Jones

Eucharist – John Sam Jones

The Antidote – Kathleen Freeman

An Artistic Mission – Emyr Humphreys

Go Play with Cucumbers – Crystal Jeans

Without Steve – David Llewelyn

all the boys – Thomas Morris

A Cheerful Note – Emyr Humphreys

DISORDERLY WOMEN

The Conquered – Dorothy Edwards

The Doctor’s Wife – Rhys Davies

Parting – Jane Edwards

A Most Moderate Lust – Siân James

The Romantic Policewoman – Rhys Davies

The Dead Bear – Crystal Jeans

TRANSFORMATIONS

A Cut Below – Jon Gower

Posting a Letter – Mihangel Morgan

Blind Date – Jane Edwards

One June Night: A Sketch of an Unladylike Girl – Amy Dillwyn

Nightgown – Rhys Davies

The Conquest, or a Mail Companion – Anonymous (I. H.)

Wigs, Costumes, Masks – Rhys Davies

My Lord’s Revenge – Anonymous

HAUNTINGS AND OTHER QUEER FANCIES

Miss Potts and Music – Margiad Evans

The Collaborators – Anonymous

The Haunted Window – Margiad Evans

A House that Was – Bertha Thomas

The Man and the Rat – Pennar Davies

Nobody Dies… Nobody Lives… – Ken Etheridge

The Fishboys of Vernazza – John Sam Jones

QUEER CHILDREN

The Water Music – Glyn Jones

The Formations – Dylan Huw

Strawberry Cream – Siân James

The Wonder at Seal Cave – John Sam Jones

Kissing Nina – Deborah Kay Davies

INTERNATIONALISMS

Fear – Rhys Davies

The Stars Above the City – Lewis Davies

Love Alone Remains – Mihangel Morgan

Muscles Came Easy – Aled Islwyn

The Largest Bull in Europe – Kate North

CHRONOLOGICAL INDEX

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Modern Wales by Parthian Books

Copyright

Kirsti Bohata is Professor of English Literature and co-Director of CREW, the Centre for Research into the English Language and Literature at Swansea University. Her books include Postcolonialism Revisited: Writing Wales in English (UWP, 2004), Rediscovering Margiad Evans: Marginality, Gender and Illness (UWP, 2013), and Disability in Industrial Britain: A Cultural and Literary History of Impairment in the Coal Industry, 1880-1948 (MUP, 2020).

Mihangel Morgan was a lecturer on modern Welsh literature, folklore and creative writing at Aberystwyth University for twenty-three years. He won the Prose Medal at the National Eisteddfod in 1993 and has published many poems, stories and novels, including Melog, translated by Christopher Meredith (Seren, 2005). He writes a regular column in the Welsh language magazine O’r Pedwar Gwynt (From the Four Winds).

Huw Osborne is Associate Professor in the Department of English, Culture, and Communication at the Royal Military College, Kingston. His books include Rhys Davies (University of Wales Press, 2009), Queer Wales: The History, Culture, and Politics of Queer Life in Wales (University of Wales Press, 2016), and The Rise of the Modernist Bookshop: Books and the Commerce of Culture in the Twentieth Century (Ashgate, 2015; Routledge 2019).

queer square mile

Queer Short Stories from Wales

Edited By

Kirsti Bohata, Mihangel Morgan and Huw Osborne

Introduction

‘there was a man in this place one time by the name of Ned Sullivan, and a queer thing happened to him coming up the valley road from Durlas.’

–Frank O’Connor,The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story(1962)

Frank O’Connor did not share our contemporary notion of ‘queer’ when he opened his seminal book on the short story with these words. His point was that the short story emerged from communal story-telling tied to a local sense of ‘this place’ – one’smilltir sgwâr [square mile] as it is called in Wales. The word ‘queer’ has changed in meaning over time. From meaning ‘odd’ and then being used as a term of abuse to describe mainly gay or effeminate men or mannish women, it has been reclaimed. It is now a positive and powerful term to describe LGBT lives and cultures. In a broader sense, it also refers to cultural and critical thinking that challenges received norms, troubles assumptions and creatively upends conventions.

The short story is particularly suited to exploring such queer ex-centric experiences and perspectives. Frank O’Connor explains how, over time, communal, local and usually oral stories—which drew on and reinforced a sense of place and shared experience—evolved into a modern ‘private art intended to satisfy the standards of the individual, solitary, critical reader’, an art particularly conducive to the outsider experience.1 The stories in this collection echo O’Connor’s contention that the short story ‘has never had a hero. What it has instead is a submerged population group … outlawed figures wandering about the fringes of society [… instilling] an intense experience of human loneliness’.2 It favours ‘tramps, artists, lonely idealists, dreamers, and spoiled priests’; it is ‘romantic, individualistic, and intransigent’.3 In its ex-centric perspectives it has the ability to unsettle, but also to show alternative ways of living.

About a decade before O’Connor’s study, Rhys Davies—who features prominently in this collection and who certainly shared some of our notion of ‘queer’—described the short story in similar terms: ‘In contrast to the novel, that great public park so often complete with great drafty spaces, noisy brass band and unsightly litter, the enclosed and quiet short story garden is of small importance and never has been much more.’4 This private, intimate and cultivated space needn’t appease the views of the wider public market of the novel. Unlike O’Connor, however, Davies sometimes claimed, as he did in a letter to the American author and editor Bucklin Moon, that the short story never entirely lost the qualities of its ancient and communal roots, so that the private and ex-centric tale may also, paradoxically, be the national one:

Short stories, like one’s first love, have always remained sweet to me. I like the spread and space of novels, in which one can do much more secret and indirect teaching—and even preaching—and handle themes which make one feel a bit like God, but in the short story one can be, so to speak, more human. There is a fire-side, pure tale-telling quality in short stories and they can convey with much more success than the novel the ancient or primitive, the intrinsic flavour of a race or people.5

Davies associates short stories with the personal intimacy of ‘one’s first love’ and opposes them to the God-like preaching of the novel. This intimacy, furthermore, is also the fire-side intimacy of a people connected to a place and a past (which Davies expresses in racialised assumptions of his time). Here the short story is conceived in the tension between public communities and private selves, national belonging and intimate love. So the queer short story of Wales is often doubly ex-centric, expressing national and sexual marginalities that are not always easily reconciled.

The short stories collected here span nearly two hundred years. The earliest—anonymous—contribution is from 1837, the year of Queen Victoria’s coronation. The most recent are three new, previously unpublished stories by Dylan Huw, David Llewellyn and Crystal Jeans. Understandings of sexuality and gender have transformed more than once during in this period. In the nineteenth century, gender rather than sexuality was the more rigidly policed element of identity, and so it is apt that ‘The Conquest, or a Mail Companion’ (1837) portrays dashingly romantic female masculinity in a woman who remains a ‘hero’ even after we know she is not the gallant young man her companion believes her to be. Gender is also the focus of Amy Dillwyn’s ‘One June Night: the Story of an Unladylike Girl’ (1883), in which a tomboyish girl (a staple figure of queer writing) tries to fill her father’s shoes while reaching across class boundaries. By the end of the nineteenth century, the work of sexologists such as Havelock Ellis and Sigmund Freud had transformed understandings of sexuality and identity. Sex was now more than an act or even a matter of sexual orientation: sexuality itself had become an identity and homosexuality a pathological form of gender and sexual ‘inversion’.

Homosexual acts between men were illegal in Britain throughout the nineteenth century, while sexual relationships between women were misrecognised and rendered invisible. As the twentieth century got underway, queer women were increasingly under suspicion while queer men lived at the risk of imprisonment, blackmail, loss of employment, loss of family, and public shaming until well into the twentieth century. The repressive environment, however, also led to alternative spaces of desire and sociability, such as gay balls (as seen in Davies’s ‘Wigs, Costumes, Masks’ (1949)), bachelor apartments (as seen in ‘The Collaborators’ (1901)), lesbian domesticities (as seen in ‘A Modest Adornment’ (1948) and ‘Nadolig/Christmas’(1929)), erotic tourism (as seen in ‘The Stars Above the City’ (2008)), cruising parks and ‘cottages’, gentlemen’s clubs and gay and lesbian bars (as seen in ‘Muscles Came Easy’(2008)). It also led to literary creativity as writers turned to coded ways of expressing same-sex desire – repeated use of the word ‘rhyfedd’ meaning ‘odd’ and ‘strange’ in Kate Roberts’s stories of intense female friendship, for instance, invites the reader to imagine what is not, or cannot be, articulated. The situation began to change in 1957 with the high-profile publication of the Wolfenden Report, which recommended the decriminalisation of homosexuality between two men in private. By 1967, two years before the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village, New York, this recommendation was finally passed into law – in large part due to the reasoned and eloquent support and advocacy of Leo Abse, Labour MP for Pontypool.

While a Welsh MP was instrumental in changing the law, and Wales benefitted as part of the UK, it is helpful to understand something of the specific cultural contexts of Wales. The short stories collected here derive from two distinctive linguistic cultures, though the stories, like the cultures, share many points of correspondence. Meic Stephens’sCydymaith i Lenyddiaeth Cymru [Companion to Welsh Literature], says that ‘It is impossible to begin to understand modern literature in Wales [in Welsh] without paying appropriate attention to the contribution and influence of Nonconformism, and the reaction to it.’6 English-language literature from Wales also contributed to and was influenced by Nonconformism, but there is a much longer Welsh-language tradition of reading and writing ‘in the shadow of the pulpit’.7 At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, Wales was still a predominantly Welsh-speaking country, working-class and chapel-going. People learned to read in the Sunday schools and most reading material was religious in nature. This was due in large part to the fact that the few who had the necessary education and leisure to write in Welsh tended to be mostly ministers of religion. Their work in Nonconformist women’s publications such asY Gymraes[The Welshwoman] andY Frythones [The Britones]was often moralistic in tone, on themes of temperance or, in the mid-nineteenth century and in response to explosive claims in a government report that Welsh women were sexually and morally lax, on the theme of the Virtuous Woman.

The novels of Daniel Owen in the late nineteenth century and Kate Roberts’s first collection of short stories published in 1925 were two watershed moments, with Saunders Lewis claiming that the short story in Welsh had ‘taken a definite step into the world of artistic creation’.8 Roberts was a freethinking individual, but even her stories deal with the matter of sex indirectly and arguably all the more finely for that. The lyrical opening sequence of one of her great novelsTraed Mewn Cyffion [lit. Feet in Stocks, or Feet in Chains] (1934), for instance, opts for a subtle and coded way of telling the reader that her recently married protagonist has just become pregnant. Reticence in the treatment of sex and sexuality was perhaps unsurprising given the scandalised reaction to bolder representations. Prosser Rhys’s treatment of the sexual development of a young man, including a (negative) reference to a same-sex experience, had scandalised the Eisteddfod in 1924. Though it won the highest honour, the Crown, the poem was not published again in his lifetime. In 1930, Saunders Lewis published the modernist novellaMonica, full of brooding dark passion, in which the eponymous character’s erotic fantasies and strong sexual desires are the focus of the story. Lewis appealed to the precedent of the hymn-writer William Williams Pantycelyn who had dramatically depicted the sexual nature of humanity in its many variations inBywyd a Marwolaeth Theomemphus[The Life and Death of Theomemphus] (1764) andDuctor Nuptiarum(1777). In reminding readers that a writer as revered as Pantycelyn, whose hymns were sung in chapel every Sunday, had written about sex as part of life, Saunders Lewis hoped that this would lead the way to the theme being used more freely in poetry and fiction in Welsh. Indeed, in an analysis of Oscar Wilde, Lewis saw connections between sexual expression and creativity, remarking that ‘The years of his intercourse with Alfred Douglas and with London “renters” were the years in which he wrote his brilliant comedies’.9 Pennar Davies’s direct story of same-sex desire, ‘Y Dyn a’r Llygoden Fawr’ [The Man and the Rat], was published in the journalHeddiw in 1941, but for the most part Lewis’s hopes were not fulfilled until later in the century, and the word ‘pechod’ [sin] continued to be used as a synonym for sex.

Pockets of tolerance may have existed in some communities, as Daryl Leeworthy’sALittle Gay History of Waleshas shown, but for many, despite decriminalisation in 1967, the stigma of homosexuality (especially for gay men) continued across Wales and the UK. The AIDS crisis in the 1980s (addressed in John Sam Jones’s ‘Eucharist’ (2003)) led to widespread fear and vilification of gay men, as well as further restrictive legislation by Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, including Section 28 of the Local Government Act (1988) prohibiting the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools (as seen in ‘The Wonder at Seal Cave’(2000)). By the 1990s, partly arising from the political activism born from protesting the poor Conservative response to the AIDS crisis, a more public and organised LGBTQ consciousness began to take shape in Wales.10 The word ‘queer’ took on its current political and theoretical meanings; Stonewall Cymru was established in 2003; and the public imagination of Wales underwent a queering through twentieth- and twenty-first-century cultural industries, education reform, legal reform, and civic and national revitalisation. This history is not, however, simply a case of ‘progression’ from closet to pride parade. As seen in the later stories in this collection, this latter era of reform is not one of straightforward liberation or progress but increasing complexity and persistent challenges.

Queering Chronologies

While such historical and national contexts are instructive, one must be careful when placing queer texts within them or alongside them. Queer critical historians question whether or not sexual identities can be reliably recovered as we look to the past from our present political position. For instance, one might think of this collection as part of the work of queer ‘recovery’ of lives that have been lost, hidden and forgotten. This is very important work, but it is often understood in genealogical terms that are at odds with many queer experiences. The nation itself is generally understood in narrative terms, and the story of the nation is often tied to lineage and descent, which is exclusively understood in heterosexual and patriarchal conceptions of time, no less so in Wales’ national anthem, ‘Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau’ [Old Land of My Fathers]. Such an uncovering of the queer past in and through the heteronormative ordering of national time risks reproducing that order.

A book like this one is part of that project of creating a common feeling for the queer Welsh experience, but must also be mindful of the limitations and respectful of the real barriers to conceiving such coherences. As Jeffrey Weeks—one of the most influential historians of sexuality, and a gay activist originally from the Rhondda—has explained:

Identities were important. But they were troubling, and they caused trouble, they disrupted things. We need them to give a sense of narrative continuity and ontological security. They provide meaning and support. They locate us in a world of varying possibilities. They help to get things done. But identities also had their downside: they were limiting, they fixed you, potentially trapped you, even the new identities that emerged in the wake of gay liberation. Identities were not enough – or perhaps they were too much.11

Weeks suggests that we must sometimes make the necessary error (what Richard Phillips calls ‘strategic essentialism’12) of identification. That is, recovery (or looking back into the past to find and acknowledge queer sexualities) is important even at the risk of projecting contemporary identities into the past. These same contemporary identities, conversely, are limiting in the present: one comes out into an identity that makes sense within a dominant heteropatriarchal order. So, as Weeks argues, the task was not to ‘celebrate, but to question, not to confirm a settled history but to problematize, not to systematize the past or order the present, but to unsettle it’.13

These questions pose problems for the anthologist. There seems to be no ideal way forward, so what compromises does one make in the ‘strategic essentialism’ of the editor’s work? Each story speaks to particular literary, social, historical, political and ideological contexts, yet presenting the stories in an unfiltered chronological form might suggest traditions and identities where no such coherences existed. Similarly, grouping the stories by identities—such as gay men, lesbians and transgender—essentialises queer experiences and harks back to the efforts of Victorian sexologists to capture and contain sexual variation by taxonomy. To resolve this conflict between the need for historical reference and the dangers of suggesting limiting traditions and identities, this book dates all stories (and a list of stories in chronological order can be found at the back of the book for those who want it) but organises them in broad thematic terms. Within each theme, the stories are not presented in any chronological order, but with a view to highlighting dialogue across times and places and in the hopes that new and spontaneous connections can be made. We are well aware that these categories are arbitrary and limiting in their own ways. A story like Jane Edwards’s ‘Blind Dêt’/‘Blind Date’ (1976),14 which is placed in ‘Transformations’, might just as easily be placed in ‘Queer Children’, as might Rhys Davies’s ‘Fear’. We placed ‘Fear’, perhaps provocatively, in ‘Internationalisms’, a section which could have included Pennar Davies’s ‘Y Dyn a’r Llygoden Fawr/The Man and the Rat’ about a Russian scientist or Thomas Morris’s ‘all the boys’, with its twist on the typical queer plot of going abroad to find sexual liberation. We might also have created other categories, such as ‘Working-Class Stories’ or ‘Queer Artists’, but at some point one must choose one’s ‘necessary errors’ and hope for the best.

Identities

Likewise, we have selected stories on the basis of the content rather than the sexual identities of the authors. A list of biographies that focus on LGBTQ identities in the context of this work might misleadingly create an artificial pantheon of historically representative figures that have been restored to some idealised and essentialised queer heritage. Moreover, can we use a set of historically shifting categories with any confidence, particularly if the people themselves didn’t use them? Rhys Davies may have been ‘out’ to a knowing circle of friends, but can we state with any certainty that he identified as a ‘gay man’? In ‘Wigs, Costumes, Masks’, for example, Mr. Simon has not been identified by the policemen of 1940s and 1950s London, not simply because Davies dared not speak his name in the repressive context of his time, but also because maybe Davies wasn’t looking to establish that identity either. It might be more appropriate to see Mr Simon as a decentring figure that makes us less comfortable identifying sexualities of the past. Davies’s contemporary, Glyn Jones, shares much of Rhys Davies’s queered childhood experiences, as suggested in the long short story ‘I Was Born in the Ystrad Valley’ (1937) or his bildungsromanIsland of Apples(1965), and Tony Brown has identified a sublimated homoeroticism in Jones’s writing.15 Nevertheless, Jones was married for sixty years to the same woman, although, only three years after his marriage, he was chafing against the constraints of middle-class domesticity.16 Evidence of sexual identities, therefore, is ambiguous and incomplete, so speculation about writers’ sexualities is inevitably far less productive than appreciations of the queer texts they produced. That said, since we are writing in a context where queer lives are still not fully acknowledged, including the deliberate exclusion of same-sex relationships from biographies, it is worth sketching in something of the personal lives of some of the authors who appear in this anthology without presuming to impose categories upon them.

Amy Dillwyn (1845–1935) regarded her close friend as her wife and wrote openly about female same-sex desire inA Burglary(1883) andJill(1884), and explored the power of cross-dressing in her first novelThe Rebecca Rioter (1880). As a successful industrialist in later life, she considered herself a ‘man of business’ and was known for her mannish clothes and cigar. Bertha Thomas (1845–1918) was part of feminist and female-orientated literary circles in London, including the group associated with the ‘Eminent Women’ series (to which she contributed a volume on the cross-dressing, cigar-smoking George Sand). Thomas, who never married, was friends with Vernon Lee, Amy Levy (with whom she rode atop the London omnibuses as immortalised by Levy in the queer ‘Ballade of an Omnibus’(1889)), and Helen Zimmern, with whom she shared a house in Canterbury. Margiad Evans (1909–1958) had a passionate sexual relationship with Ruth Farr, to whom—along with her beloved Professor (publisher Basil Blackwell)—she dedicated one of her journals. After her marriage, she and her husband kept up a friendship with Ruth. In Bloomsbury, Dorothy Edwards (1903–1934) lived for a time with David Garnett and his wife, with whom Margiad Evans was also friendly (although not during Edwards’s time). Edwards maintained close relationships with women she met at university,17 though her relationship with Kathleen Freeman, another author in this anthology, was bumpy. Kathleen Freeman (1897–1959) taught Edwards Greek at Cardiff University; as her academic senior and social superior (Freeman was very comfortably off while Edwards with only a widowed mother was always short of money), Freeman could exercise somewhat imperious authority. In literary terms, however, Edwards was easily her equal. Edwards’s Rhapsody was published to acclaim in 1927, the year before Freeman’sThe Intruder and other Stories. Freeman lived with her life-long partner Dr. Liliane Clopet, a GP and author, until her death.18

Also making her mark in the twenties with modernist short fiction, in Welsh rather than English, was Kate Roberts (1891–1985). She was at the heart of the Welsh intelligentsia that was forging the new nationalist party—Plaid Cymru—and a new modernist literature. She married Morris T. Williams, the lover of Prosser Rhys, whose 1924 Eisteddfod poem ‘Atgof’ [Memory] had touched on same-sex desire. In a recent biography of Roberts, Alan Llwyd quotes from a letter of October 1926 in which Roberts recounts the powerful effect of an encounter with ‘un o’r merched harddaf y disgynnodd fy llygaid arni erioed’ [one of the most beautiful women I have ever set eyes upon].19 This beguiling woman was the wife of a butcher with whom she stayed after giving a lecture in Pontardawe, and who the following morning kissed Roberts ‘ar fy ngwefus’ [on my lips]: ‘Nid oedd dim a roes fwy o bleser imi. Os byth ysgrifennaf fy atgofion, bydd y weithred hon yno…’ [Nothing has given me more pleasure. If I ever write my memoirs, this event will be in them…].20 Llwyd sees this encounter as an influence on the short story ‘Nadolig – Stori Dau Ffyddlondeb’ (1929) [‘Christmas – A story of two companions’] which is published in English translation in this volume. It was composed around the same time as Roberts’s letter and in it Miss Davies bestows a similarly understated but momentous kiss. The story also, as Llwyd points out, explores the choice between same-sex love and conventional marriage which Prosser and Morris would both have to make.21 Roberts later wrote about male same-sex ties that eclipse a heterosexual betrothal inTegwch y Bore (1967).22

The freethinking writer and intellectual, Pennar Davies (1911–1996), also nurtured an intimate connection with a male friend, largely by letter. A theologian and Congregational Minister, Davies was married (with five children) to Rosemarie Wolff, a refugee from Nazi Germany who learned Welsh. As a doctoral student in the late 1930s at Yale University in America, he met and formed a close friendship with Clem C. Linnenberg who would go on to become a successful Washington economist. Linnenberg, whose wife also came from Germany, maintained a lifelong correspondence with Pennar and Rosemarie, sending regular gifts and generous donations to ‘The House of Davies’.23 The short story ‘Y Dyn a’r Llygoden Mawr’ [‘The Man and the Rat’] (1941) was inspired by scientific experiments conducted at Yale while Davies and Linnenberg were students. In 1966 Pennar dedicatedCaregl Nwyf [Chalice of Passion], in which ‘Y Dyn a’r Llygoden Mawr’ was collected for the first time, to ‘Marianne a Clem Linnenberg, enaid hoff, cytûn’ [‘soulmate’]. His title comes from a line in Dafydd ap Gwilym’s poem ‘Offeren y Llwyn’: ‘caregl nwyf a chariad’ [‘a chalice of passion and love’], while his dedication comes from a poem by R. Williams Parry that talks of walking the wooded path alone or with ‘enaid hoff, cytûn’, literally ‘a special or favoured soul, in agreement’. Davies was a member of the freethinking Cadwgan group; his thinly veiled portrait of that group in the novelMeibion Darogan (1961) includes a portrayal of female same-sex desire.

Such visible and veiled forms of male bonding was one subject of Ken Etheridge’s (1911–1981) art. His paintings show the influence of queer pornographic art of the 1950s, and his homoerotic ‘Rugby Changing Room, Carmarthen’ is on display at the World Rugby Museum in the south stand of Twickenham Stadium. As a playwright, artist and poet, he drew on Welsh mythology and symbolism to explore sexual identity in his public work, while his unpublished archives—from which the story included here is taken—show more directly the experience of being gay in a period when homosexuality was illegal.

We cannot, of course, know how any of these now deceased writers viewed their own sexualities at any one point in their lives, still less their changing sense of them over time. Nor can we say that all or any of the contemporary writers included in this anthology identify with the terms and categories that attempt to describe human sexuality currently in circulation. Mihangel Morgan, for instance, has questioned the usefulness of ‘queer’ for Welsh and Welsh language non-heteronormative experience:

When Queer Nation was formed [in North America] in the 1990s, its founders did not confer with the people of the world, and they did not ask the people of the Rhondda valley if they approved of it. The word ‘queer’ in South Wales is still an insult and hurtful; hardly anyone there knows that it has been ‘reappropriated’ by academics… The decision to use the term ‘queer theory’ was not arrived at by some kind of international democratic consensus; rather, it has been imposed on us through a form of imperialist, American linguistic annexation.24

The use of ‘queer’ has, perhaps, broken out of academic circles and into Welsh popular culture, as exemplified by well-established queer events, such as Aberystwyth’s regular ‘Aberration’ nights, the presence of ‘Queer Cymru’ on Twitter and the regular Pride Cymru parade. In Welshcwiyr—a homophone of queer which also neatly subverts the Welsh word for ‘correct’ (cywir)—is being adopted by some. But this is not to say that all have embraced the term ‘queer’; it is still an uncomfortable term for many. We have used it here for its flexibility and its inherent resistance to taxonomies. Ultimately, while we recognise the value in making queer lives in history visible, we much prefer to let the stories themselves trouble and unsettle one’s sense of the sexual past, present and future.

A Note on Form

The formal innovations of the short stories collected here range from a kind of unreliable realism to modernist experimentation, magical realism and playful postmodernism. A large number of the stories date from the 1920s through to the 1950s, possibly reflecting both the significance of the modernist short story in Wales and the appetite amongst modernist writers to explore questions of sexuality.

The short story is often regarded as a characteristically modern genre with formal features that share many of the characteristic attributes of modernist writing in general, ‘particularly the cultivation of paradox and ambiguity, and the fragmented view of identity’.25 The stories of Glyn Jones, for example, convey a modernist surrealism that refuses a singular, authoritative, rational and external perspective. The lyricism of ‘The Kiss’ (1936) shifts perspectives in a sensuous and sensual symbolist abstraction. ‘The Water Music’ (1944) is told through a nearly epiphanic stream-of-consciousness, and both of these stories exemplify the ‘inward turn’ toward psychological realism. Kate Roberts, Margiad Evans and Rhys Davies write stories whose narrative voices succumb to the partial knowledge of their characters. The revelations, therefore, in such stories as ‘Nadolig’, ‘A Modest Adornment’ and ‘The Romantic Policewoman’ (1931) are never completely exposed, so readers must engage with these subjective experiences and push against the conventions that constrain the characters. In the same way that the techniques of modernist stories refuse ‘an ordered approach to fiction and the hierarchical world-view it embodies’,26 these stories of paradoxical repression and revelation challenge master narratives that limit the range of sexual and national belonging. As Adrian Hunter has claimed,

The interrogative short story’s ‘unfinished’ economy, its failure literally to express, to extend itself to definition, determination or disclosure, becomes, under the rubric of a theory of ‘minor’ literature, a positive aversion to the entailment of ‘power and law’ that defines the ‘major’ literature.27

In Jorge Sacido’s words, the short story often conveys the ‘subject’s experience of a desire which ideology cannot accommodate’.28

A second ‘wave’ of queer short stories at the turn of the century and into the twenty-first arguably corresponds with a surge in confidence and desire to articulate multiple Welsh identities in post-devolution Wales. This second wave varies considerably in form: while ‘modern’ elements of form and technique persist into the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the later stories in this collection are more likely to exhibit a postmodernist play and a critique of the stability of such notions as identity, gender, nation, language, as well as the narratives that uphold them. For example, the future tense point of view sustained throughout Morris’s ‘all the boys’ (2015) gives one the uncertain impression of a possible future outing rather than a confirmed past action. The ‘end’ of the story is held in abeyance, and one is perhaps doubtful that ‘when they cross the Severn Bridge, and see theWelcome to Wales sign, all the boys will cheer’. Kate North’s ‘The Largest Bull in Europe’ (2014) has an ‘unfinished’ ambiguity and symbolist suggestiveness that sits comfortably within the modernist tradition; however, its queer tourist voyeurism stands at an ironic distance from the privileged masculine gaze that dominated ethnographic perspectives in the early twentieth century. Similarly, Lewis Davies’s ‘The Stars Above the City’ (2008) presents a decentred queer Welsh take on orientalised gay desires associated with earlier queer figures like Andre Gide.

Perhaps the most self-consciously postmodern story in the collection is Mihangel Morgan’s ambiguously titled story ‘Cariad Sy’n Aros yn Unig’ (1996), translated by the author as ‘Love Alone Remains’. Presented as reconstructed from Welsh-language letters sent to the author by an Austrian student, and here rendered in English, the story collapses distinctions between fiction and reality, language and experience. The fragments that make up the story have been curated by the silent participant in the correspondence. The sense of curated completion is in tension with the sense of absence and incompletion, so we are left in the fraught spaces in which language only provisionally makes sense of the world (and the nation) and our places in it.

The formal varieties of these stories—whether modern, postmodern, realist or surrealist—address several common themes that we hope will foster meaningful dialogue across the times, places and ‘identities’ of queer Wales.

Love, Loss, and the Art of Failure

The stories in this first section deal with ways of loving, making contact, and desiring in and alongside queer relationships. Because so many of these connections are made in contexts that are hostile to their expression, many of them are characterised by loss or the fear of loss. The defiant isolation of lovers is matched by trauma, denial, exile and failure. For example, Stevie Davies’s ‘Red Earth, Cyrenaica’ (2018) is a story of repression, trauma and loss, but it is also a love story in both the past and the present in which the wife’s love of her husband is more deeply touching for her queer embrace of her husband’s pain.

So loss and failure should not be understood in straightforwardly negative terms. When so much of the queer experience is marked by ‘failures’ to succeed within conditions that are hostile to queer love and queer life, ‘failure’ may be preferable to success:

Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world. Failing is something that queers do and have always done exceptionally well; for queers, failure … can stand in contrast to the grim scenarios of success that depend on ‘trying and trying again.’29

The reward of failure, according to Halberstam, is the escape from ‘the punishing norms that discipline behaviour and manage human development with the goal of delivering us from unruly childhoods to orderly and predictable adulthoods’.30 We see this failure in Kate Roberts’s ‘Nadolig’/‘Christmas’, in which Olwen’s experience of queer intimacy transforms her impending marriage into a ‘grim scenario of success’ which will happento her rather than be something she willingly does. When she finally hears her intended husband’s shout, ‘she felt something like a knife going through her soul’.

Similarly, Glyn Jones’s stories present experiences of oddness that defamiliarise the world so that ‘[e]veryday things are registered, especially in moments of emotion, as strange, as other’.31 This oddness, again echoing O’Connor, often expresses ‘alienation from environment and community’,32 which registers a discontinuity with the dominant forms of life surrounding his isolated characters. In ‘Knowledge,’ (1937) for instance, an odd and distant collier harbours a displaced intimate sensual knowledge that is suggestive of unspoken desires. In ‘The Kiss,’ two loving brothers are unafraid to mingle wounding with sensual desire. In a kind of celebratory religious sublimation, the brothers’ queer touch bears witness to the shared suffering of industrial labour.33

The celebration or moment of articulation of love is contained within several of the stories centred on loss and grief. The opening story, ‘Y Trysor’/‘The Treasure’ (1972), charts a series of ‘failures’ and losses: the desertion of a cruel husband (a shock to the community, a welcome release for his wife), Jane Rhisiart’s realisation that all of her children are selfish, and finally her grief at the great loss of her friend, Martha Huws. This final loss, which she understands as ‘the first great sorrow of her life’, is also a celebration of ‘the treasure’ of their intense twelve-year bond. Similarly, death and a possible betrayal of loyalty is the vehicle that provides the final epiphany of a ‘secret but weary fidelity’ in ‘A Modest Adornment’ by Margiad Evans.

Kathleen Freeman uses adversity to bring together the protagonists of ‘The Fraying of the Thread’ (1926). In this story, a young woman embarks on a test of her own faithfulness by wooing a woman driven to the edge of sanity by previous (self-imposed) losses. Freeman’s stories engage with ethical and moral standards, outlining a set of personal and spiritual behaviours worthy of uncompromisingly intellectual, unconventional young women. In this way, her stories have a somewhat Victorian bent, though their structure is modern.

Death and betrayal are the fulcrum on which two contemporary stories by David Llewellyn and Crystal Jeans pivot, though in unexpected ways which are ultimately celebrations of love more than loss. In ‘After Steve’, Steve’s towering presence at the heart of a queer family continues to reverberate after his premature death, so much so that his diminutive coffin is a surprise. Crystal Jeans’s contemporary ‘Go Play with Cucumbers’ displays her typically subversive humour, taking a lesbian cliché and turning it on its head, though Lou’s extreme response to the consumption of cucumbers can be read in more obviously Freudian ways.

The final two stories are about getting drunk and not quite coming out. Published nearly fifty years apart, Thomas Morris’s ‘all the boys’ (2015) follows a rowdy stag do to Dublin, while Humphreys’s ‘A Cheerful Note’ (1968) takes us on a trip from an unorthodox interview in which the men are asked to parade their heterosexual prowess to the multicultural environs of Cardiff docks (expressed in the racialised language of the day). It is a geographical remove reminiscent ofDorian Gray, in which the ethnically diverse space of the docks is connected with an exotic cocktail of sex, intoxication and danger. In Humphreys, the energy of the docks allows the queer protagonist briefly to upend the heteronormative hierarchy which has defined the evening.

Disorderly Women

The women in these stories are disruptive, disorderly, and often dangerous to the patriarchal social order. Detached, powerful (and occasionally desperate) women invade heterosexual marriages and fantasies proving to make far more attractive partners than the blinkered, arrogant and sometimes violent men who consider themselves the centre of the world.

Jane Edwards’s ‘Gwahanu’/‘Parting’ (1980), Rhys Davies’s ‘The Doctor’s Wife’ (1930), and Siân James’s ‘A Most Moderate Lust’ (1996) all portray husbands whose wives are moving away from the heterosexual domestic order into alternative relations between women. In ‘The Doctor’s Wife’, the husband fails to see and recognise the queer relationship before his eyes, demonstrating how romantic and sexual relationships between women were socially ‘ghosted’, in Terry Castle’s sense of being only partially perceived, seen but misrecognised, haunting and troubling the security of the heterosexual home.34 Davies’s use of harp music in ‘The Doctor’s Wife’ to symbolise female sexuality (which is contrasted to the ‘swelling’ phallic masculine music of male-voice choirs), is similar to Dorothy Edwards’s expression of queer desire through music in ‘The Conquered’ (1927). The latter story is told from the perspective of a bookish young man with an aesthetic view of the world returning to the country home of relations on the borders of Wales. Here, he encounters ‘a very charming Welsh lady’, Gwyneth, with whom his youngest cousin Ruthie has a subtle intimacy. Ruthie, who used to be ‘something of a tomboy’, clings close to Gwyneth and slyly expresses her love by singing Brahms’An Die Nachtigall.The narrator disapproves of the choice of music, but in response he waits for a nightingale in a wood near Gwyneth’s house, fantasising about her appearance, thus making clear the meaning of Ruthie’s song. Gwyneth favours more lively tunes, singing Schumann’sDer Nussbaum, a song about walnut blossom mimicking a lover’s kiss and a maiden yearning for a declaration of love. Ruthie responds by planting a nut tree outside Gwyneth’s window, to the bafflement of the narrator. This may well be an allusion to a Bavarian – and wider European – tradition of ‘Liebesmaie’ in which a May Tree (usually a birch) is left outside a woman’s window as a sign of love and devotion. The narrator thus participates in a queer courtship that he never quite perceives, leaving one wondering whether he knows just what is it that he ‘wanted to say’.

In Siân James’s ‘A Most Moderate Lust’, a man’s mistress and wife grow closer as he grows farther from both. The contact between the two women destabilises the mistress/wife compartmentalisation through which he maintains his definitions of masculinity. When the two women step out of his categories, he is no longer able to see them as complete people, telling himself that they ‘don’t make up one real woman between them’. As the romantic dynamics in the house slip out of his control, he thinks ‘of the time when he had – naturally enough – imagined Rosamund, small and lively, with curly black hair and round green eyes, to be the complete antithesis of his cool and beautiful wife’. Ultimately, he cannot perceive what ‘lusts’ are satisfied. In ‘Parting’, on the other hand, the husband thinks too much about the possible intimacies between his wife and her best friend, though he struggles to bring himself to say – perhaps even to think – what, exactly, he suspects. He knows that ‘he hated having a drunken woman in his bed’, but the obsessive jealousy that mounts as he loses his place in the imagined order of his home is the most destructive force in the story.

In ‘The Romantic Policewoman’, a gendered domesticity is the fantasy of the queer figure herself. So enmeshed is she in policed gender codes, she deceives herself into viewing her predatory and controlling behaviour as moral rescue. But she, too, is finally far more disorderly than she purports to be, and her intervention briefly disrupts the latent violence that underpins the relationship between Kathleen and Fred Collins.

Transformations

This section deals with the construction and transformation of gender identities. Concerned with clothing, performance, costume, disguise, and embodiment, these stories remind us that ‘transvestism is a space of possibility structuring and confounding culture: the disruptive element that intervenes, not just a category crisis of male and female, but the crisis of category itself’.35 This category crisis is seen in one of the principal Welsh figures of transformative embodiment, Jan Morris. Morris, whose memoirConundrum(1974) remains among the most important narratives of transsexual experience, is particularly relevant here for the ways in which she figures this transformation in national terms, aligning her gender reassignment with Welsh belonging. The land and myths of Wales, she says, were more accommodating to her changeling experience. In one scene, while she is well into her hormone therapy but has not yet undergone sexual reassignment surgery, she enters the waters of The Glyders and stands ‘for a moment like a figure of mythology, monstrous or divine’ before she falls ‘into the pool’s embrace’. Sometimes, she thinks ‘the fable might well end there, as it would in the best Welsh fairy tales’.36 The liquid indeterminacy of landscape and legend accommodates her uncategorised body within what she elsewhere calls ‘The Matter of Wales’. In one way or another, all of the stories in this section disrupt and intervene in this ‘matter.’

One such national embodiment is found in Jon Gower’s playful revision of Welsh rugby masculinity in ‘A Cut Below.’ Rugby, long associated with ‘boozy machismo and sublimated homoeroticism’,37 is celebrated in this story for its camp theatricality. The hyperbole of the narrative voice recalls the fireworks, the sparkly face-paint and costumes of the fans, the ritual songs, which are as much part of the national game as what happens on the pitch. The protagonist, Keiron, is the site at which spectacle and sport come into the most destabilising focus. Keiron is a mixture of celebrity mystique, commodity fetishism, and mythic transcendence of the every-day. Before his surgeries, he is a mercurial figure of fame, media representation, cosmetics, and athletic fantasy, ambiguously poised between embodiment and disembodiment:

Keiron was the embodiment of rugby skill, powered by huge heart and guts, guided by innate intuition and blessed with an ability to read a game like a Gareth, a Barry, or Shane… Keiron was a shape-changer, able to turn from corporeal rugby player to untackleable wraith in a magic breath. An alchemist, too, able to transmute the meatiness of a defense into a whisp of smoke.

In this passage and throughout the story, the embodied experience is changeful and immaterial. However, if the story collapses distinctions between sex, gender and sexuality, it does so while admitting the lived importance of embodied gender. The final arbitrary misidentification of ‘hisproper gender’ suggests that Keiron is on the cusp of achieving a body that will, when she wakes, be realised.

The cultural authority of Mihangel Morgan’s Welsh bard in ‘Postio Llythr’/‘Posting a Letter’ (2012) gets a similarly humorous treatment. This story, too, however, has a much more serious intent in redressing the oppressive masculinity within which its accommodating narrator struggles. The story is as much about gender and power as it is about the need for visibility, and both characters may in fact be finding a way out from under the authority of The Bard. Jane Edwards’s ‘Blind Dêt’/‘Blind Date’ deals with embodiment and the construction of gender in the context of class. The men the narrator desires are dreamy abstractions of class mobility, and she seems far more interested in women’s cosmetics and clothing than she is in sexual intercourse. She is disgusted by both her mother’s breast-feeding body and the rural body of her date, but also disappointed by the ill-fitting costume of feminine respectability – the choir dress – in which she dresses up. Her dream of romantic social mobility is also a longing to escape this world of base heterosexual embodiment, despite her (revealing) anxiety over unstable gender categories.

Amy Dillwyn’s ‘One June Night’ is similarly concerned with the social scripts and signs which govern gender identity. The opening reads like a set of stage directions, inviting us to read each prop for symbolic significance. The governess flicks through the fashion pages ofQueen,while the pupil ‘is absorbed in one of Mayne Reid’s novels’, most of which were adventure stories set in the American ‘wilderness’. Rejecting her governess’s attempts to socialise her into a superficial femininity, Margery claims a connection with the natural world, which is a masculine space in this story. On hearing some magpies chatter after dark, Margery wonders ‘whatever that can mean’, to which Miss Stokes retorts ‘There’s no meaning in all the silly noises birds are always making’. Margery puts her firmly in her place, but the central argument about ‘meaning’ in the story is over gender (as understood within a specific class context). For Miss Stokes it is ‘unheard of’ for a girl, still less ‘alady’, to behave like ‘a boy’ or to do the work of ‘a [game]keeper’. Margery reads her position differently; she is her father’s representative as the only member of the family in the house. While her governess regards it a great misfortune that her charge is ‘rough, wanting in all gentle and refined ideas, hard, and unfeeling’, the story shows Margery to be anything but wanting in feeling. Her compassion reaches across the barriers of class to leave a lasting moral impression on the poacher she has caught, thus demanding a reappraisal of ‘the attributes of a true lady’.

Likewise, the legibility, commodification and provisionality of gender are central in Rhys Davies’s ‘Nightgown’ (1942), in which the central character’s body is an embattled site of class-based constructions of femininity and masculinity. Dressed and increasingly behaving like one of the monosyllabic colliers she tends, a miner’s wife is systematically worn out by an industrial machine that eventually leaves her collapsed and black-faced, like a victim of a mining accident. Her demise is brought on in part by starvation in the cause of purchasing a pristine white satin nightgown she has seen in the window of a drapers’ shop. It is uncertain whether it symbolises luxury or femininity, and, of course, the two are closely connected.

A rather different kind of dashing, romantic female masculinity shored up by class privilege is portrayed in ‘The Conquest, or a Mail Companion’. Yet another story in which conquest and mistaken assumptions are at the fore, the title of the story is a pun on the apparently ‘male’ companion on the coach named ‘Conquest’. While the end of the story apparently defuses the amorous fantasies of the young girl, she becomes a devoted servant and permanent resident in the house of the female ‘hero’ with the ‘free voice’ who first ‘rescue[d]’ her from the fate of governess.

‘Wigs, Costumes, Masks’ is set in London when ‘the queer was a dangerous incursion into the defining space of Britishness’.38 This incursion led ‘to a culture of knowingness, emphasizing the practical utility of beat officers’ immersion in the realities of metropolitan lowlife, crime and vice.’39 The two detectives investigate Mr. Simon, a costume dealer whom they suspect of some undisclosed crime and whose shop sits in ‘a district devoted to the night entertainment of the flesh’. Mr. Simon ultimately eludes their gaze through a fantastic display of theatrical illusion that travesties their rational fact-finding need to place Mr. Simon within clear and criminalised sexual categories.

Theatricality again comes to the fore in ‘My Lord’s Revenge.’ Appearing inThe Weekly Mail of 1890, this story portrays thefin de siècle conflict between, on the one hand, nineteenth-century gender as defined within stable notions of public and private and, on the other hand, sexual, racial, commercial, and aesthetic challenges to that stability. The story revolves around the relationship between Lady Anthony Hopeland, the wife of a Conservative Lord in elected office, and Girly Grey, a beautiful and effeminate actor with a flair for cross-dressing. Girly’s threat is evident in his influence on women, for ‘he had been the favourite of several posturing, lolloping, Liberty-silked damsels’. The intersection between gender, race, commerce, and aesthetics is signalled by the reference to Liberty silk, which was at the time cashing in on exotic eastern fabrics and designs while collaborating with members of the Arts-and-Crafts movement and figures in the theatre world.40Lady Anthony plays ‘the boy’ to Girly Grey in their quasi-theatrical liaisons, until Lord Anthony eventually returns to put ‘his house in order’ with the help of his friend His Excellency Kami Pasha. The men hide behind a curtain to witness the gender-inverted playmaking, and Girly (whose gender is never directly redefined) is punished by being sold to Kami Pasha for his Harem in Cairo. This last act of colonialist containment reasserts British patriarchal mastery while simultaneously exiling sexual deviance into the relative safety of exotic orientalist eroticisms. However, like many stories that try to reassert traditional gender categories, this one, too, cannot entirely ease the anxieties it raises. The masquerading Girly Grey is never unmasked; rather, he recedes behind the further mysteries of both the Harem veil and commodity fetishism. This fetishised veil simultaneously reveals and conceals the orientalist fantasies upon which Lord Anthony’s equally masquerading performance of his public and domestic power is staged.

The final story in this section, ‘The Dead Bear’ by Crystal Jeans, sends up the stereotype of the murderous lesbian. In a plot which brings to mind Rhys Davies’s novelNobody Answered the Bell(1971) in which two lesbians keep the body of a murdered stepmother in an attic, ‘The Dead Bear’ combines knowing melodrama – ‘Nobody does drama like a lesbian’ – with the acutely observed materiality of an early-morning estate after a night getting drunk: ‘I head down the path slowly, toward the garage, placing my bare feet down carefully like a blind woman in case I step on glass or shit or slugs.’

Hauntings and other Queer Fancies

The stories in this section exploit the generic strangeness of the gothic, fantasy and science fiction. The gothic has a well-established connection with sexual otherness and queerness, and early gothic writing helped to shape the way we think about sexuality. It is a genre of fear, desire and excess that delights in the uncanny discomfort of crossing the borders between supposedly stable binary opposites. George Haggerty explains that ‘the cult of gothic fiction reached its apex at the very moment when gender and sexuality were beginning to be codified for modern culture. In fact, gothic fiction offered a testing ground for many unauthorized genders and sexualities’.41 The spectral, disembodied, and apparitional have provided ways of writing about same-sex affinities while keeping physical consummation of these desires obscure and immaterial. These spectral affinities offer queer desire as a possibility tantalisingly in view but as yet unrealised. In ‘Miss Potts and Music’ (1948) by Margiad Evans, the narrator is haunted by the image of a young girl. Constance Potts’ gift for music (an artform Margiad Evans saw an articulation of the spirit) breaks through physical and social barriers to touch the narrator like some ‘spirit colour’. Ghosts and premonitions bring women together in one of Evans’s previously unpublished stories, ‘The Haunted Window’ (1953) and likewise in Bertha Thomas’s ‘A House that Was’ (1912). In both, the imminence of death provides the impetus for intimacy, while a ghostly image – the beautiful portrait of a dead sister in Thomas and a grotesque picture of sickness in Evans – provides a connecting point within an erotic triangle. Ghostly, artistic collaboration confirms the intimacy between two writers in ‘The Collaborators’. The men who share ‘a subtle and mysterious aura of mutual attraction, when the world would have looked for a wave of mutual repulsion’ find a fraught communion through art and death and through success that is also failure. The ghostliness of their bachelor affections is inevitable and impossible, and the double-entendre of the title conveys the criminality from which their death-driven creative consummation both escapes and derives.

Other stories of fantasy, surrealism, magic realism, and dystopian science fiction exploit these genres’ tendency to challenge the assumptions of normative ‘reality’. In Rosemary Jackson’s terms, these stories expose ‘the basis upon which cultural order rests’; they open up ‘on to disorder, on to illegality, on to that which lies outside the law, that which is outside the dominant value systems’ to trace ‘the unsaid and the unseen of culture: that which has been silenced, made invisible, covered over and made “absent”’.42 Pennar Davies’s ‘Y Dyn a’r Llygoden Fawr’ [‘The Man and the Rat’] presents a compelling yet troubling portrait of a Nietzschean ‘Űbermensch’. Commonly translated as ‘superman’ and associated with eugenicist and fascist strains of thought as suggested in Davies’s story, Űbermensch also means ‘beyond human’. Davies’s pairing of his arrogant yet vulnerable scientist with the cleverest lab rat in a narrative that alternates between their first-‘person’ perspectives, is a comic twist on this, as is the Rat’s belief that he is being controlled by entities beyond his understanding. Of course he is, but his confidence that some higher force will rescue him contributes to his final downfall.

Ken Etheridge’s ‘Nobody Dies… Nobody Lives…’ (c. 1950s) contrasts a sterile future world of health and perfection – ‘built on the slopes of the highest mountains in the west’ – with the vitality of a radical perversion and obscenity. In this questionable utopia, ‘the effetism of incurable cancers, which men tried to palliate with obscenities and perversities’, have been eradicated, and the ‘weak, the perverted, the criminal were not allowed to breed’. The protagonist is queer by virtue of the fact that he is a carrier of just this kind of life-threatening disease, a disease that forces the re-embodiment of the community. In one scene, he encounters beautiful bodies trapped in an ageless, unregenerative heterosexuality in which the dangers of an unpredictable and therefore monstrous future have been eradicated along with the possibility of children and new life. This monstrosity is figured vividly on the mountain where the elderly who cannot let go of the past stand numbed by old pop songs. They are surrounded by a frieze of wild, chaotic sensuality, crossing boundaries of male and female human and animal bodies with orifices confused between ‘mouths, nostrils, eyes, and vaginas’. The imagery suggests Etheridge’s paintings of the stories of the Mabinogion with their magical transformations. In the end, the protagonist’s contamination brings death and therefore life – his perverse criminal corruption becomes the source of life for the young women who feel a ‘strange stirring in their bodies’ and the young men who ‘moved among them, embracing and laughing and touching’. The protagonist’s difference forces ‘a future that opens out, rather than forecloses, possibilities for becoming real, for mattering in the world.’43

In John Sam Jones’s ‘The Fishboys of Vernazza,’ (2003) the sexualising and exoticising gaze of the touring lovers takes a surreal turn as they notice mermen painted on the rocks and reproduced on rings worn by the handsome young men attending to their needs. The image relates to a local legend: ‘when the sea istempestoso, the fishboys come into the village through thegrotto, and take away… how you say?… They take away the bad boys’. When they ask how bad a boy must be to be charmed away, they are told ‘Bad enough that…lui è desiderabile’. They soon notice that the young men they desire have discreet gills behind their ears, and the story ends with the entrance of ‘the local transvestite’ whose black lace panties are ‘too skimpy to hide her fishy tail’. This fantasy is played out against the more mundane emotional background of the two lovers’ relationship, which is troubled by two irreconcilable visions of gay intimacy. At the end of the story, they begin to trade perceptions but still move in opposite directions. The barriers to a shared life together at home are contrasted to the shape-changing fluidity of the fishboys, which may be nothing more than a reflection of their own desire for a connection that is manageable only when they are away travelling in erotic-exotic landscapes of queer possibility.

Queer Children

This section contains stories of childhood, youth, coming-of-age, sexual awakening, and gender and sexual formation. Queer theorists of childhood like Lee Edelman and Kathryn Bond Stockton have argued that the idea of the child has been burdened with too much meaning as a figure of idealised past innocence, future hope, and developmental normativity.44 However, stories of childhood lead one backwards from adulthood into a remembered strangeness, a state of being before words such as ‘gay’ or ‘straight’ had particular meaning.45 Stockton’s description of the fantasy of childhood applies well to these returns to childhood perspectives and the queer possibilities that these returns open up. She asserts that, despite efforts to render the child simple, innocent, pure, and utterly knowable,

the child has gotten thick with complication. Even as an idea. In fact, the very moves to free the child from density – to make it distant from adulthood – have only made it stranger, more fundamentally foreign, to adults. Innocence is queerer than we ever thought it could be. And then there are the bodies (of children) that must live inside the figure of the child. Given that children don’t know this child, surely not as we do, though they move inside it, life inside this membrane is largely available to adults as memory – what can I remember of what I thought I was? – and takes us back in circles to our fantasies (of our memories).46

The unrecoverable recovery of childhood in these stories unravels the arbitrary progression toward heteronormativity. In ‘The Water Music’, Glyn Jones’s surreal representation of childhood is conveyed in the immediacy of the present tense, indifferent to the distance in time between the author’s writerly sophistication and the child’s sensuous experience. Removed from the patterns of the town and the ministrations of adults, the child’s imagination swims through a world of boyish play that is indifferent to the boundaries between bodies, animals, nature, and genders. One boy stands ‘tall and lovely-limbed… garlanded and naked in a dance-dress of sunlight flimsy-patterned with transparent foliage’. Another is as ‘beautiful as Sande or some musk-scented princess’. The act of diving is more than a rite of passage or entrance into the brave world of boyish play; it is an act of praise for this crossing of a threshold into ever more fluid, various, and excessive realms of being. Other unruly children are found in Siân James’s ‘Strawberry Cream’ (1997) and Deborah Kay Davies’s ‘Kissing Nina’ (2008). In James’s story, the eleven-year-old girl’s sexual hungers belie the supposed innocence of children who should have a passion for nothing more than chocolate. The narrator’s return to this unforgettable memory reverses the not-yet-straight narrative of child development. Similarly, in ‘Kissing Nina’, Grace’s supposedly more appropriate heterosexual growth is aggressively pushed away. Grace’s memory is suspended in the stillness and darkness of her winter kissing of Nina and resists the sexual awakening of spring romance with a boy. In each of the stories in this section, then, the queer child offers other ways of growing up alongside normative patterns and formations of identity.

Internationalisms